Abstract

National studies of Parkinson’s disease (PD) provide critical data for healthcare planning, yet methodological limitations continue to undermine their utility. This review examines recent epidemiological work, including the Greek nationwide analysis, to highlight three priority areas for refinement: diagnostic accuracy, survival methodology, and recognition of disease heterogeneity. Misclassification due to reliance on ICD codes and overlap with drug-induced or vascular parkinsonism inflates prevalence estimates, while crude mortality measures fail to account for competing risks and comorbidities, exaggerating PD-specific risk. Stratification by age at onset remains underutilized despite clear genetic, clinical, and socioeconomic differences between early- and late-onset PD. Integrating administrative data with registries and biobanks, adopting digital biomarkers and AI-based diagnostic tools, and applying competing-risk and longitudinal survival models can generate more accurate and policy-relevant estimates. Equity considerations—ensuring representation of women, minorities, and rural populations—are essential for generalizable findings. Refining methodological standards in PD epidemiology is not only a technical necessity but also a prerequisite for equitable care, rational resource allocation, and progress in neurodegeneration research.

Keywords

Parkinson’s disease, Epidemiology, Diagnostic accuracy, Case ascertainment, Competing risk analysis, Survival models, Administrative data, Health disparities, Neurodegeneration, Public health policy

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disorder, with global prevalence estimates exceeding six million individuals [1], and projections suggesting that more than nine million people were affected by 2020 [2]. Note that single-year counts (for example, “2020”) are estimates that vary with demographic ageing and case-ascertainment methods; for context, the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study estimated 6.1 million people with PD in 2016 and 8.5 million in 2019 [3], and more recent GBD-based analyses report case counts approaching 11–12 million by 2021 [4]. Clinically, PD is characterized by both motor symptoms, such as bradykinesia, rigidity, resting tremor, and postural instability, and a broad spectrum of non-motor manifestations, including cognitive impairment, autonomic dysfunction, sleep disorders, depression, and hyposmia. This dual motor and non-motor profile contributes substantially to disability, reduced quality of life, and mortality [5].

From a mechanistic standpoint, PD is traditionally associated with dysfunction of the basal ganglia, resulting from the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra, which leads to nigrostriatal insufficiency. Yet, pathogenesis extends beyond dopamine depletion. Synaptic and axonal degeneration, compensatory processes in the early stages of the disease, and the selective vulnerability of neuronal subtypes all contribute to shaping the onset and progression of the disease. Furthermore, degeneration of non-dopaminergic systems, including noradrenergic, serotonergic, and cholinergic pathways, helps explain the heterogeneity of PD’s motor and non-motor features. Pathologically, the disease is defined by α-synuclein aggregates within Lewy bodies, with toxic oligomeric and fibrillar species propagating in a prion-like manner across brain regions. These processes connect PD to broader neurodegenerative pathways and emphasize its complexity as more than a single neurotransmitter disorder [6]. Advancing age is the strongest risk factor [3], while environmental exposures such as pesticides, occupational history, urate levels, use of anti-inflammatory drugs, traumatic brain injury, and exercise show variable or conflicting associations with risk [7,8].

While global estimates highlight the scale of the challenge, national-level epidemiological studies provide the granular data necessary for health system planning and policy development. In this context, the recent analysis by Makris et al. [9] of PD incidence, prevalence, and mortality in Greece represents a valuable contribution. Such studies are essential to capture regional patterns, assess resource needs, and inform public health responses. However, their utility is limited when methodological issues such as diagnostic misclassification, reliance on crude mortality metrics, and lack of stratification by age at onset are not addressed. These blind spots restrict both interpretation and comparability across populations.

This review builds on recent national studies and their critiques, arguing that refinements in diagnostic accuracy, survival methodology, and recognition of disease heterogeneity are urgently needed. Only by strengthening these methodological foundations can PD epidemiology truly inform patient counseling, guide resource allocation, and anticipate the societal impact of an aging global population.

This invited review aims to identify and prioritize methodological improvements needed to capture the true burden of PD, with a focus on case ascertainment/diagnostic validity, appropriate survival and competing-risk methods, age-at-onset stratification, and geographic and equity considerations, and to provide concrete recommendations for future epidemiologic research.

Case Ascertainment Challenges

Reliable epidemiology begins with accurate case ascertainment. In PD, however, achieving diagnostic precision continues to be a substantial challenge because of overlap with atypical Parkinsonism, vascular Parkinsonism, and drug-induced syndromes, which reduces specificity, while coding errors and differences between high- and low-resource settings further increase misdiagnosis risk. These factors introduce systematic bias into prevalence and survival estimates.

Many large-scale epidemiological studies depend heavily on International Classification of Diseases (ICD), 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes (e.g., G20 = idiopathic PD; G21 = secondary Parkinsonism) and prescription databases. These sources offer clear advantages, low cost, broad coverage, and ease of access in countries with centralized health systems, but they also introduce a substantial risk of misclassification. Hill et al. [10] demonstrated that ICD-coded PD diagnoses in electronic health records are often inaccurate and, importantly, vary by race, with lower diagnostic accuracy among Black patients. This finding underscores how code-based approaches can perpetuate systematic error and even exacerbate health disparities. Similarly, Peterson et al. [11] showed that administrative diagnostic codes overestimated PD incidence by 73%, with a positive predictive value of only 46%. Such evidence highlights a critical limitation: while coding systems capture many true PD cases, they also misclassify a large number of non-PD patients, making them unreliable as the sole basis for precise epidemiological estimates.

Misdiagnosis is a persistent challenge in PD epidemiology, with overlapping clinical features from other Parkinsonian syndromes leading to diagnostic inaccuracy, inappropriate treatment, and biased prevalence estimates. In one of the most influential clinicopathological studies, Hughes et al. [12] reported a clinical diagnostic accuracy of 76%. More recent meta-analyses place pooled accuracy at approximately 70–83%, with lower sensitivity in early or atypical presentations [13]. Drug-induced parkinsonism (DIP) and vascular parkinsonism (VP) further reduce specificity and are often misclassified as PD, particularly when case definitions rely on ICD-10 codes (G20) and prolonged dopaminergic therapy [9], thus risking systematic bias in prevalence and mortality estimates unless administrative algorithms are validated and diagnostic performance (PPV, sensitivity, specificity) is reported [14,15].

Diagnostic accuracy also varies substantially across healthcare systems. In high-resource settings, access to neurologists, advanced neuroimaging, and validated diagnostic criteria improves the reliability of PD case identification. By contrast, in low-resource regions, diagnosis is often made by general practitioners without specialist input, and confirmatory tools are limited or absent. These constraints lead to higher rates of misclassification and delayed recognition, reducing the generalizability of epidemiological findings across countries and risking systematic underestimation of the true burden of PD in underserved populations. Together, these diagnostic challenges underscore the need for standardized case definitions, specialist involvement, and careful methodological design to strengthen the accuracy of PD epidemiology worldwide [16].

Future refinements in diagnostic accuracy may come from emerging digital technologies, which offer scalable, objective, and accessible solutions to many of the challenges facing PD epidemiology. Digital biomarkers collected through smartphones, wearable devices, and artificial intelligence have the potential to reduce misdiagnosis by capturing subtle, disease-specific motor and non-motor features that are often indistinguishable in routine clinical evaluation. Arora et al. [17] demonstrated the feasibility of this approach in a pilot study, where smartphone-based assessments of voice, tapping, gait, and posture were able to detect and monitor PD symptoms in real-world settings. Recent automated machine learning frameworks that combine multimodal data, genomics, clinical markers, and wearable sensor-derived features have achieved AUCs of around 0.90 for PD prediction, illustrating the feasibility of integrated digital biomarker models in epidemiological surveillance [18]. Crucially, such tools can be deployed remotely, making them not only cost-effective but also particularly valuable in low-resource settings where access to neurologists and advanced neuroimaging is limited.

Beyond diagnosis, AI-driven approaches demonstrate substantial potential for revolutionizing PD care by enabling treatment personalization. By integrating multiple data modalities with advanced machine learning algorithms, these models can support earlier detection, continuous and more accurate monitoring, and optimization of therapeutic interventions [19]. As these technologies mature, integrating them into national epidemiological studies could complement traditional diagnostic pathways, reduce reliance on administrative coding, and ultimately deliver more accurate and equitable estimates of PD burden worldwide.

Mortality and Survival Metrics: Beyond Crude Estimates

Crude mortality estimates in PD are fundamentally limited because they fail to account for competing causes of death, such as ischemic heart disease, cancer, and respiratory illness. In older age groups, these comorbidities dominate overall mortality, meaning that unadjusted figures often inflate PD-specific risk. Makris et al. [9] themselves acknowledged this limitation, noting that their reported case fatality rates (CFRs) and mortality rate ratios (MRRs) do not reflect the risk from the time of diagnosis, and that non-neurological causes, including cardiovascular, respiratory, and infectious diseases, contribute substantially to the observed mortality. The methodological literature reinforces this concern. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Macleod et al. [20] reported standardized mortality ratios (SMRs) of approximately 1.5–2.0 in PD, reflecting a 50–100% higher risk of death compared with the general population. However, they also emphasized the wide heterogeneity across studies, much of which was attributable to whether or not competing risks were considered. Studies relying on crude or unadjusted survival analyses consistently overestimated PD-related mortality, because most patients are elderly and therefore at high risk of dying from other common causes. Macleod and colleagues concluded that ignoring competing outcomes obscures the true contribution of PD to mortality and complicates comparisons between populations. Cohort-based data support this interpretation. Fernandes et al. [21] studied a Brazilian PD cohort and found that deaths frequently resulted from indirect complications such as aspiration pneumonia, falls, and cardiovascular disease, rather than PD itself. Similarly, Forsaa et al. [22] in a 12-year prospective follow-up of newly diagnosed PD patients in Norway, reported that mortality was nearly twice as high as in the general population. The strongest predictors of reduced survival were dementia, postural instability, and older age at onset, while levodopa responsiveness did not affect long-term outcomes. Together, these findings highlight that PD survival is shaped more by non-dopaminergic features and comorbidities than by motor symptom control alone. Both studies reinforce the argument that crude mortality rates exaggerate PD-specific risk by conflating deaths directly attributable to PD with those caused by secondary or competing conditions. To address these limitations, competing-risk models provide a more reliable framework for survival analysis. Traditional Kaplan–Meier (KM) methods censor deaths from non-PD causes and thus implicitly assume those individuals remain at risk for PD-related death, which can overestimate event probabilities when competing causes are common. In contrast, cause-specific hazard models estimate the instantaneous risk of PD-related death, while Fine–Gray sub distribution models quantify its cumulative probability in the presence of competing events. Presenting both cumulative-incidence functions (CIFs) and cause-specific results, as outlined in methodological tutorials [23], yields estimates that are clinically meaningful and policy-relevant, better reflecting the multimorbid reality of older PD cohorts and supporting more accurate counseling, forecasting, and health-system planning. Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated the interpretation of mortality data in PD. Excess mortality during 2020–2021 was observed globally among older, multimorbid groups that overlap substantially with PD cohorts. In Italy’s Veneto region, PD-related deaths rose sharply in 2020, with age-standardized mortality increasing by 19% when PD was the underlying cause of death (UCOD) and by 28% when listed as any cause Multiple Cause of Death (MCOD), showing peaks during the first and second pandemic waves [24]. Clinical cohorts likewise reported high fatality rates among PD patients with COVID-19, ranging from 19.7% in multicenter studies to 35.8% in hospitalized samples, largely driven by comorbid dementia, hypertension, and longer disease duration [25]. However, these excess deaths mirror broader population trends and likely reflect both direct infection effects and indirect consequences of disrupted care, rather than a PD-specific vulnerability. Hence, post-2020 mortality data should be interpreted cautiously and contextualized against general population mortality and healthcare disruption indicators.

Recognizing Heterogeneity: Early vs. Late-Onset Parkinson’s Disease

Heterogeneity by age at onset is an underappreciated dimension of PD epidemiology. Early-onset PD (EOPD), often defined as symptom onset <50 years, is enriched for pathogenic variants (PARK2/parkin, PINK1, DJ-1) that alter susceptibility and clinical course [26,27]; patients with EOPD suffer disproportionate treatment-related complications (notably premature levodopa-induced dyskinesias) despite a typically slower motor progression [28], and they face long-term socioeconomic burdens (higher cumulative DALYs, prolonged care needs and psychosocial impact). Approximate incidence: EOPD (≤50–55 years) is uncommon (~0.5–2 per 100,000 person-years), whereas incidence rises steeply with age. Among people ≥65 years, it commonly reaches approximately 100–200 per 100,000 person-years in high-income settings [4]. These large age differences argue for routine age-stratified reporting and separate analyses rather than pooled overall estimates. By contrast, late-onset PD, the dominant phenotype in most epidemiologic cohorts, is more strongly influenced by lifestyle and environmental factors and is associated with faster motor decline, more frequent non-motor symptoms, and a greater comorbidity burden (frailty, polypharmacy) that complicates diagnosis and prognosis [29]. Pooling EOPD and late-onset cases in effectiveness or survival analyses risks diluting subgroup-specific effects and exaggerating overall mortality; stratification improves precision for etiologic inference, service planning, and targeted interventions (genetically directed strategies for EOPD versus comorbidity- and environment-focused strategies for late-onset PD) [30].

Geospatial and Environmental Determinants of Parkinson’s Disease

An improved PD epidemiology requires stratification by onset age. Genetic, clinical, and socioeconomic differences, when implemented, will not only enhance epidemiological accuracy but also align research more closely to the realities of patient care and healthcare planning.

The prevalence of PD is strongly influenced by geography, indicating that contextual and environmental exposures are key determinants of risk. Global Burden of Disease analyses show pronounced regional differences and substantial increases in absolute case counts across East and South Asia between 1990–2021, with higher age-standardized incidence in high-SDI countries and lower rates in many low-SDI settings [4]. Beyond genetic susceptibility, exposures to heavy metals, industrial chemicals, and pesticides have been consistently implicated, with higher prevalence observed in rural, agricultural, and industrialized regions. Multiple epidemiologic studies, both case-control and cohort, demonstrate that exposure to pesticides such as paraquat and rotenone, which cause oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, significantly increases PD risk [31–33]. Population-based research from agricultural areas such as California’s Central Valley provides further evidence of this link [32,34]. Collectively, these mechanistic and population-level findings reinforce that environmental neurotoxicity contributes to PD through the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons to oxidative injury. Concurrently, protective groups have arisen, highlighting the multifactorial etiology of disease susceptibility. Regular consumption of coffee, for instance, has again and again been associated with reduced PD risk in a variety of populations, potentially by adenosine receptor antagonism or modulation of neuroinflammation [35,36]. Likewise, following Mediterranean dietary habits, high in antioxidants and polyphenols, may reduce neurodegeneration via anti-inflammatory mechanisms. More recently, urban epidemiological research has demonstrated that exposure to green and blue spaces is associated with lower PD risk, which implies that reduction in air pollution, reduction in stress, and increased encouragement of physical activity may have neuroprotective effects [37,38]. These findings emphasize the need to take into account environmental resilience factors in addition to risks. The incorporation of geospatial epidemiology is a grand methodological frontier. The alignment of lifetime residential histories with exposure databases and genetic data enables more refined causal inference. Such methods can explain why clusters of incidences arise in intensively pesticide-exposed agricultural areas, in intensely pollutant-exposed industrial corridors, or in less protective urban environments. This view also highlights the need for longitudinal designs because cumulative and infant exposures could prove to be the determining factor in the risk of later PD. Policy-wise, these results have real-time implications. Regulatory caps on pesticide usage, industrial discharges, and city pollution not only satisfy more general concerns about public health but could also function as population-level interventions against neurodegenerative disease prevention. Furthermore, expenditure on city green infrastructure and encouragement of dietary interventions could act as scalable, non-pharmacologic methods to abate PD burden. Geospatial and environmental determinants, therefore, need to shift from the margins to the mainstream of PD epidemiology as well as public health planning.

Health System and Policy Implications

The epidemiology of PD is not only of scientific interest; it has immediate and widespread implications for the health system and policy. With the prevalence still on the rise worldwide, PD has been termed a "Parkinson pandemic" due to demographic aging, enhanced survival, and potentially higher incidence [39]. Lacking reliable and precise epidemiological information, healthcare systems are ill-prepared to predict the magnitude of forthcoming demand, resulting in inadequately provided neurology care and fragmented provision.

Precise estimates of burden are essential for rational workforce planning. Regional differences in prevalence and mortality rates should inform the allocation of neurologists, movement disorder specialists, rehabilitation services, and long-term care facilities. Integrated models of patient-centered PD care, focusing on multidisciplinary teams and coordinated networks of services, have been advanced as a model for reorganizing chronic neurological care [40]. Yet the success of these models will depend on accurate epidemiological underpinnings. Crude estimates or underreporting risk misallocating scarce resources, leaving high-burden regions underserved.

The economic burden of PD also underscores the need for strict epidemiology. In Europe, each year's societal cost per patient has been estimated at more than €13,000, with indirect costs of lost productivity and informal care making up the largest proportion [41]. Comparable studies in the US also indicate an economic cost of over $14 billion every year, with forecasts predicting increasing costs as prevalence continues to grow [42]. Global Burden of Disease data also project an accelerating upward trend, especially in low- and middle-income nations where the health system is less equipped to manage the burden [3,43] Equity issues exacerbate these systemic problems. Women, minorities, and rural residents continue to be underrepresented in PD research; meta-analyses confirm that minority enrollment in PD clinical trials is extremely low [44]. Because policy and payment models are frequently based on epidemiological estimates, truncated or biased data threaten to institutionalize inequities. It is thus essential to overcome these limitations not just for precision but also for justice in healthcare planning. Finally, advanced epidemiology, integrating diagnostic accuracy, survival analyses, and social determinants, becomes the key to efficient health system design. Policymakers rely on such information in order to distribute resources equitably, forecast caregiving demand, and develop sustainable long-term approaches for a fast-growing population of patients.

Equity and Representation in Parkinson’s Disease Research

While Makris et al.’s [9] study offers valuable national-level insights into PD in Greece, it also underscores a broader challenge: the equitable representation of diverse populations in PD epidemiology. Addressing this is critical for ensuring findings are generalizable, interventions are inclusive, and health disparities are identified and remedied.

Underrepresentation of women, minorities, and rural populations

Clinical trials and epidemiological research in PD vastly underrepresent certain demographic groups. A meta-analysis of nearly 8,000 PD trial participants showed that studies reporting race/ethnicity were rare, and when they did, 75.8% of participants were White, while African Americans and Hispanics represented only 0.2% and 0.6%, respectively [44]. Racial and ethnic disparities persist not only in research enrollment but also in clinical diagnosis and access to care: non-White individuals are less likely to receive neurologist-led care, which correlates with worsened outcomes [45]. Beyond race and ethnicity, sex-based disparities exist in both PD prevalence and care. Although men have traditionally shown higher PD prevalence, the male-to-female prevalence ratio has been estimated at ~1.18 (95% CI: 1.03–1.36), with lower ratios reported in some Asian populations [46]. Women with PD also experience disparities in access to advanced therapies (e.g., deep brain stimulation) and often receive less aggressive management of non-motor symptoms [47].

Geographic and socioeconomic disparities

Rural populations frequently face a disproportionate PD burden because of differential environmental exposures, limited healthcare access, and underdiagnosis. A population-based analysis in Canada documented socioeconomic variations in PD prevalence and incidence, illustrating how area-level factors influence measured burden [48]. In Victoria, Australia, PD prevalence was higher in rural than urban localities, and some high-prevalence clusters were geographically associated with pulse crop production (a proxy for rotenone/pesticide exposure), even after demographic adjustment [49]. Global analyses show that health inequalities for neurodegenerative diseases widened between 1990–2019, suggesting socio-demographic development can paradoxically accentuate disparities [50].

Contextual implications for Greece and future strategies

Greece, with its complex blend of rural and urban demographics, shifting migration patterns, and regional healthcare variability, likely mirrors these global disparities, though data remain limited. Makris et al.'s [9] geospatial findings present an opportunity: disaggregating data by sex, rural vs. urban locality, and socioeconomic strata could illuminate inequities masked in aggregate estimates.

To improve representation and accuracy in PD epidemiology, future efforts should:

- Develop inclusive registries that oversample marginalized groups and rural populations to ensure representativeness.

- Harmonize methodology across regions to allow consistent comparisons and equitable inclusion of diverse subgroups.

- Report demographic variables such as race/ethnicity and sex routinely, and set enrollment targets reflective of population distributions—strategies increasingly recommended in trial design literature [51,52].

- Engage in community outreach and education, especially targeting underrepresented groups, to enhance awareness, diminish mistrust, and improve participation in research [53,54].

Future Directions in Parkinson’s Epidemiology

To move from descriptive snapshots “codes and counts” toward actionable, patient-centered epidemiology, three linked developments are essential: (A) integrate prescription/administrative data with clinically validated registries and biobanks and routinely validate/report algorithm performance (PPV, NPV, sensitivity, specificity) and share exact code lists; (B) adopt digital health tools (wearables, digital biomarkers, AI) as complementary surveillance only after external validation and with robust privacy/governance; and (C) routinely apply modern survival/longitudinal methods (report cumulative incidence functions; use Fine-Gray models for absolute risk and cause-specific hazards for etiologic questions, considering joint/multi-state models for progression). These steps will sharpen case ascertainment, enable earlier detection and continuous monitoring, and produce survival estimates that better reflect disease-specific risk.

Integrate registries, biobanks, and multi-omic cohorts with administrative data

Prescription databases like the one used by Makris et al. [9] offer near-complete coverage and scalability, but they lack clinical phenotyping and molecular data that explain heterogeneity. Linking administrative records to disease registries, prospective cohorts, and biobanks (with standardized phenotyping and biosamples) enables genotype–phenotype and exposure–outcome analyses and supports causal inference. Recent time-series multi-omics integration frameworks (e.g., MONFIT) show the feasibility and value of combining longitudinal molecular data with clinical trajectories to uncover progression mechanisms and possible subtypes [55].

Use wearable devices, digital biomarkers, and AI to complement administrative surveillance

Wearable sensors and smartphone-based digital biomarkers can provide continuous, objective measures of motor (bradykinesia, tremor, freezing of gait) and non-motor features. Systematic reviews and empirical studies demonstrate that sensor + ML pipelines detect subtle motor abnormalities, quantify fluctuations, and track progression signals that episodic clinic visits miss. Digital outcomes are promising as both trial endpoints and surveillance triggers that can prioritize patients for neurologist assessment or registry enrollment, improving the positive predictive value of administrative algorithms. Practical adoption requires cross-population validation and transparent reporting of algorithm performance [56–58].

Modernize survival analysis: competing risks, intermediate events, and dynamic prediction

Crude case-fatality ratios and simple mortality rate ratios can misrepresent prognosis when competing causes of death are common, particularly in older adults. Competing-risk methods (cause-specific hazards, Fine–Gray sub distribution models, and cumulative incidence functions) produce interpretable, age-stratified estimates of the probability of Parkinson-related outcomes in the presence of other mortality risks and should be standard in population studies of PD survival. Landmark and joint-modeling approaches that incorporate time-varying covariates (e.g., incident dementia, institutionalization, major comorbidity) help model how intermediate events change subsequent risk. Implementing these techniques will yield survival estimates that better inform patients, clinicians, and policy planners. Practical guidance and tutorials are widely available and should be adopted in future PD epidemiology work [59–61].

Operational and policy enablers

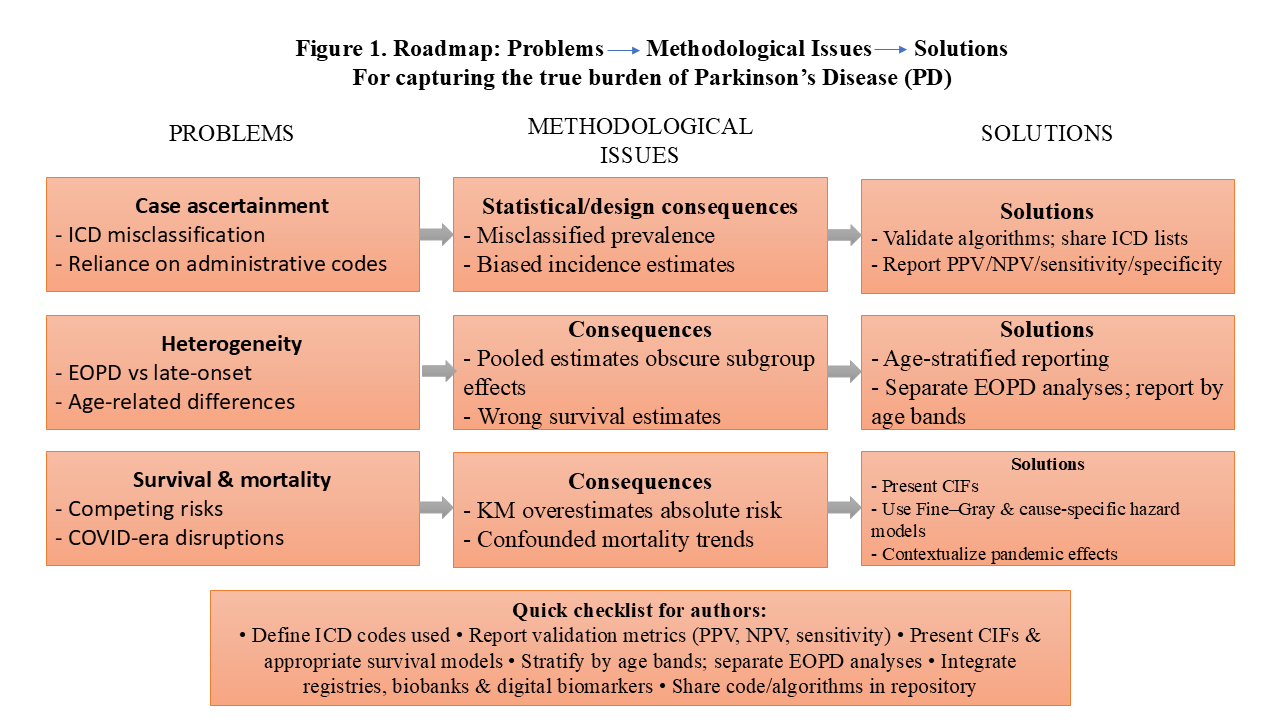

To realize these directions, funders and health systems must support: (1) linkage infrastructure and privacy-preserving governance for registry, administrative integration; (2) validation studies and regulatory pathways for digital biomarkers; and (3) analytic capacity building so competing-risk and longitudinal models are routinely applied. These investments align with the WHO Intersectoral Global Action Plan on Epilepsy and Other Neurological Disorders (IGAP; 2022–2031), which encourages integrated surveillance, registry development, and technology-enabled care [62]. Integrating registries/biobanks with administrative data, augmenting surveillance with validated digital biomarkers, and applying competing-risk/longitudinal survival methods will together transform prescription-based PD studies from descriptive tallies into precise, prognostically informative, and actionable epidemiology, extending the contributions of Makris et al. [9] into policy and prevention [55,56]. Figure 1 summarizes the principal methodological problems and recommended solutions discussed in this review.

Broader Implications for Neurodegeneration Research

The methodological concerns in PD epidemiology, diagnostic misclassification, survival bias, and insufficient stratification are mirrored across Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other dementias. Lessons from PD studies like Makris et al. [9] can inform the refinement of neurodegeneration epidemiology more broadly.

Shared diagnostic and classification challenges

Administrative data are widely used to estimate AD burden, but without biomarker confirmation or clinical validation, diagnostic misclassification is common. A U.S. Medicare validation study showed claims-based algorithms for Alzheimer’s Disease / Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (AD/ADRD) varied in accuracy, with positive predictive values depending heavily on the case definition chosen [63]. An Australian cohort CHAMP (Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project) demonstrated that linked hospital/death records underestimated dementia prevalence and had low sensitivity compared with clinical diagnoses [64]. These findings mirror PD challenges, where administrative definitions risk conflating idiopathic PD with atypical Parkinsonian syndromes unless validated [65,66].

Survival analysis across neurodegenerative diseases

Crude survival estimates obscure true prognosis when competing causes of death are frequent. Waller et al. empirically compared cause-specific Cox and Fine–Gray competing-risk models for dementia risk and found notable differences in effect estimates when death competed with the event of interest [67]. Methodological guidance recommends the use of Fine–Gray sub distribution or cause-specific hazard models rather than standard Kaplan–Meier or Cox approaches in such settings to avoid biased inference [59]. These methods apply equally to PD, where cardiovascular and oncologic mortality often intersect with neurological progression.

Environmental and genetic heterogeneity as cross-cutting themes

Environmental exposures matter across neurodegeneration. A North Carolina population study linked long-term PM2.5 exposure to increased risks of AD, other dementias, and PD admissions [68], and systematic reviews/meta-analyses support associations between PM2.5 and dementia risk [69,70]. On the genetic side, recent work documents shared or pleiotropic loci across PD, AD, and ALS (Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis), indicating overlapping pathways and reinforcing the value of integrated analytic frameworks [71,72].

Lessons from PD as a methodological model

Makris et al.’s [9] prescription-linked national surveillance demonstrates the scalability of administrative datasets for case capture. While coding specificity is a limitation, this approach provides a foundation for registry linkage and harmonized case definitions that can be extended to AD and other dementias. Combining registry infrastructure with clinical adjudication and biomarkers would improve external validity and cross-country comparability. PD epidemiology can therefore serve as a methodological blueprint for the neurodegeneration field.

Conclusion

The nationwide study by Makris et al. [9] provides useful national estimates for PD in Greece but also highlights enduring methodological challenges. To strengthen PD epidemiology, we must: (1) improve diagnostic specificity by supplementing administrative codes with clinician adjudication and biomarker data; (2) adopt refined survival analyses (competing-risk and longitudinal models) rather than crude mortality measures; and (3) stratify by age at onset because early- and late-onset PD differ in genetics, prognosis, and socioeconomic impact. Additionally, integrating regional, environmental, and social determinants is essential to explain geospatial variability and identify modifiable risks. Equity and inclusivity, ensuring women, minorities, rural residents, and under-studied global populations are represented, must be central. Technological innovation (digital biomarkers, wearables, machine learning) offers powerful complements to traditional epidemiology. Finally, global harmonization through international registries and standardized reporting (as encouraged by WHO IGAP) will be crucial to enable comparability and coordinated progress. Refining PD epidemiology is not merely methodological refinement; it is a pathway to improved patient care, better healthcare planning, and more effective prevention. By setting rigorous, inclusive standards for PD, the field can provide a model for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and contribute to a more robust and equitable global approach to neurodegeneration research.

Declarations

Limitations

This invited review focuses on methodological priorities and is not an exhaustive systematic review of all epidemiologic studies. It synthesizes evidence available through 2025 and emphasizes methodological improvements applicable across settings.

Funding

No specific funding supported this work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

2. Pauwels EKJ, Boer GJ. Parkinson's Disease: A Tale of Many Players. Med Princ Pract. 2023;32(3):155–65.

3. GBD 2016 Parkinson's Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson's disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2018 Nov;17(11):939–53.

4. Li M, Ye X, Huang Z, Ye L, Chen C. Global burden of Parkinson's disease from 1990 to 2021: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2025 Apr 27;15(4):e095610.

5. Sveinbjornsdottir S. The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease. J Neurochem. 2016 Oct; 139:318–24.

6. Ye H, Robak LA, Yu M, Cykowski M, Shulman JM. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Parkinson's Syndrome. Annu Rev Pathol. 2023 Jan 24; 18:95–121.

7. Blauwendraat C, Nalls MA, Singleton AB. The genetic architecture of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Feb;19(2):170–8.

8. Kieburtz K, Wunderle KB. Parkinson's disease: evidence for environmental risk factors. Mov Disord. 2013 Jan;28(1):8–13.

9. Makris G, Samoli E, Chlouverakis G, Spanaki C. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of Parkinson's disease in Greece. Neurol Sci. 2025 Oct;46(10):5027–34.

10. Hill EJ, Sharma J, Wissel B, Sawyer RP, Jiang M, Marsili Let al. Parkinson's disease diagnosis codes are insufficiently accurate for electronic health record research and differ by race. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2023 Sep;114:105764.

11. Peterson BJ, Rocca WA, Bower JH, Savica R, Mielke MM. Identifying incident Parkinson's disease using administrative diagnostic codes: a validation study. Clin Park Relat Disord. 2020; 3:100061.

12. Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Kilford L, Lees AJ. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of idiopathic Parkinson's disease: a clinico-pathological study of 100 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1992 Mar;55(3):181–4.

13. Rizzo G, Copetti M, Arcuti S, Martino D, Fontana A, Logroscino G. Accuracy of clinical diagnosis of Parkinson disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016 Feb 9;86(6):566–76.

14. Shin HW, Chung SJ. Drug-induced parkinsonism. J Clin Neurol (Seoul, Korea). 2012 Mar 31;8(1):15.

15. Zijlmans JC, Daniel SE, Hughes AJ, Révész T, Lees AJ. Clinicopathological investigation of vascular parkinsonism, including clinical criteria for diagnosis. Mov Disord. 2004 Jun;19(6):630–40.

16. Postuma RB, Berg D. Advances in markers of prodromal Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2016 Oct 27;12(11):622–34.

17. Arora S, Venkataraman V, Zhan A, Donohue S, Biglan KM, Dorsey ER, et al. Detecting and monitoring the symptoms of Parkinson's disease using smartphones: A pilot study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015 Jun;21(6):650–3.

18. Makarious MB, Leonard HL, Vitale D, Iwaki H, Sargent L, Dadu A, et al. Multi-modality machine learning predicting Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022 Apr 1;8(1):35.

19. Twala B. AI-driven precision diagnosis and treatment in Parkinson's disease: a comprehensive review and experimental analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2025 Jul 28;17:1638340.

20. Macleod AD, Taylor KS, Counsell CE. Mortality in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014 Nov;29(13):1615–22.

21. Fernandes GC, Socal MP, Schuh AF, Rieder CR. Clinical and Epidemiological Factors Associated with Mortality in Parkinson's Disease in a Brazilian Cohort. Parkinsons Dis. 2015; 2015:959304.

22. Forsaa EB, Larsen JP, Wentzel-Larsen T, Alves G. What predicts mortality in Parkinson disease?: a prospective population-based long-term study. Neurology. 2010 Oct 5;75(14):1270–6.

23. Austin PC, Lee DS, Fine JP. Introduction to the Analysis of Survival Data in the Presence of Competing Risks. Circulation. 2016 Feb 9;133(6):601–9.

24. Fedeli U, Casotto V, Barbiellini Amidei C, Saia M, Tiozzo SN, Basso C, et al. Parkinson's disease related mortality: Long-term trends and impact of COVID-19 pandemic waves. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022 May;98:75–7.

25. Fasano A, Elia AE, Dallocchio C, Canesi M, Alimonti D, Sorbera C, et al. Predictors of COVID-19 outcome in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2020 Sep; 78:134–7.

26. Schrag A, Schott JM. Epidemiological, clinical, and genetic characteristics of early-onset parkinsonism. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Apr;5(4):355–63.

27. Kasten M, Hartmann C, Hampf J, Schaake S, Westenberger A, Vollstedt EJ et al. Genotype-Phenotype Relations for the Parkinson's Disease Genes Parkin, PINK1, DJ1: MDSGene Systematic Review. Mov Disord. 2018 May;33(5):730–41.

28. Wickremaratchi MM, Knipe MD, Sastry BS, Morgan E, Jones A, Salmon R, et al . The motor phenotype of Parkinson's disease in relation to age at onset. Mov Disord. 2011 Feb 15;26(3):457–63.

29. Mehanna R, Moore S, Hou JG, Sarwar AI, Lai EC. Comparing clinical features of young onset, middle onset and late onset Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014 May;20(5):530–4.

30. Marras C, Lang A. Parkinson's disease subtypes: lost in translation? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013 Apr;84(4):409–15.

31. Ascherio A, Chen H, Weisskopf MG, O'Reilly E, McCullough ML, Calle EE, et al. Pesticide exposure and risk for Parkinson's disease. Ann Neurol: Official Journal of the American Neurological Association and the Child Neurology Society. 2006 Aug;60(2):197–203.

32. Tanner CM, Kamel F, Ross GW, Hoppin JA, Goldman SM, Korell M, et al. Rotenone, paraquat, and Parkinson's disease. Environ Health Perspect. 2011 Jun;119(6):866–72.

33. Seidler A, Hellenbrand W, Robra BP, Vieregge P, Nischan P, Joerg J, et al. Possible environmental, occupational, and other etiologic factors for Parkinson's disease: a case-control study in Germany. Neurology. 1996 May;46(5):1275–84.

34. Paul KC, Cockburn M, Gong Y, Bronstein J, Ritz B. Agricultural paraquat dichloride use and Parkinson's disease in California's Central Valley. Int J Epidemiol. 2024 Feb 1;53(1): dyae004.

35. Ross GW, Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, Morens DM, Grandinetti A, Tung KH, et al. Association of coffee and caffeine intake with the risk of Parkinson disease. JAMA. 2000 May 24-31;283(20):2674–9.

36. Hong CT, Chan L, Bai CH. The Effect of Caffeine on the Risk and Progression of Parkinson's Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2020 Jun 22;12(6):1860.

37. Krzyzanowski B, Mullan AF, Turcano P, Camerucci E, Bower JH, Savica R. Air Pollution and Parkinson Disease in a Population-Based Study. JAMA Netw Open. 2024 Sep 3;7(9): e2433602.

38. Jo S, Kim YJ, Park KW, Hwang YS, Lee SH, Kim BJ, et al. Association of NO2 and Other Air Pollution Exposures With the Risk of Parkinson Disease. JAMA Neurol. 2021 Jul 1;78(7):800–8.

39. Dorsey ER, Sherer T, Okun MS, Bloem BR. The Emerging Evidence of the Parkinson Pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis. 2018;8(s1):S3–8.

40. Bloem BR, Henderson EJ, Dorsey ER, Okun MS, Okubadejo N, Chan P, et al. Integrated and patient-centred management of Parkinson's disease: a network model for reshaping chronic neurological care. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Jul;19(7):623–34.

41. Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Wittchen HU, Jönsson B, CDBE2010 study group, et al. The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol. 2012 Jan;19(1):155–62.

42. Kowal SL, Dall TM, Chakrabarti R, Storm MV, Jain A. The current and projected economic burden of Parkinson's disease in the United States. Mov Disord. 2013 Mar;28(3):311–8.

43. Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TD. The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2014 Nov;29(13):1583–90.

44. Di Luca DG, Sambursky JA, Margolesky J, Cordeiro JG, Diaz A, Shpiner DS, et al. Minority Enrollment in Parkinson's Disease Clinical Trials: Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of Studies Evaluating Treatment of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1709–16.

45. Aamodt WW, Willis AW, Dahodwala N. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Parkinson Disease: A Call to Action. Neurol Clin Pract. 2023 Apr;13(2):e200138.

46. Zirra A, Rao SC, Bestwick J, Rajalingam R, Marras C, Blauwendraat C, et al. Gender Differences in the Prevalence of Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2022 Nov 14;10(1):86–93.

47. Patel R, Kompoliti K. Sex and Gender Differences in Parkinson's Disease. Neurol Clin. 2023 May;41(2):371–79.

48. Lix LM, Hobson DE, Azimaee M, Leslie WD, Burchill C, Hobson S. Socioeconomic variations in the prevalence and incidence of Parkinson's disease: a population-based analysis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010 Apr;64(4):335–40.

49. Ayton D, Ayton S, Barker AL, Bush AI, Warren N. Parkinson's disease prevalence and the association with rurality and agricultural determinants. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019 Apr;61:198–202.

50. Ji Z, Chen Q, Yang J, Hou J, Wu H, Zhang L. Global, regional, and national health inequalities of Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease in 204 countries, 1990-2019. Int J Equity Health. 2024 Jun 19;23(1):125.

51. Tsai CC, Tao B, Lin V, Lo J, Brahmbhatt S, Kalo C, et al. Representational Disparities in the Enrollment of Parkinson's Disease Clinical Trials. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2025 Jun;12(6):878–81.

52. Siddiqi B, Koemeter-Cox A. A Call to Action: Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion in Parkinson's Research and Care. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;11(3):905–8.

53. Adrissi J, Marre A, Shramuk ME, Zivin E, Williams K, Larson D. Barriers and facilitators to Parkinson's disease research participation amongst underrepresented groups. BMC Res Notes. 2025 May 29;18(1):240.

54. Sanchez AV, Ison JM, Hemley H, Jackson JD. Diversifying the research landscape: Assessing barriers to research for underrepresented populations in an online study of Parkinson's disease. J Clin Transl Sci. 2024 Feb 1;8(1):e34.

55. Mihajlović K, Malod-Dognin N, Ameli C, Skupin A, Pržulj N. MONFIT: multi-omics factorization-based integration of time-series data sheds light on Parkinson’s disease. NAR Mol Med. 2024 Oct;1(4):ugae012.

56. Hirczy S, Zabetian C, Lin YH. The current state of wearable device use in Parkinson's disease: a survey of individuals with Parkinson's. Front Digit Health. 2024 Dec 23;6:1472691.

57. Rábano-Suárez P, Del Campo N, Benatru I, Moreau C, Desjardins C, Sánchez-Ferro Á, et al. Digital Outcomes as Biomarkers of Disease Progression in Early Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review. Mov Disord. 2025 Feb;40(2):184–203.

58. di Biase L, Pecoraro PM, Pecoraro G, Shah SA, Di Lazzaro V. Machine learning and wearable sensors for automated Parkinson's disease diagnosis aid: a systematic review. J Neurol. 2024 Oct;271(10):6452–70.

59. Putter H, Fiocco M, Geskus RB. Tutorial in biostatistics: competing risks and multi-state models. Stat Med. 2007 May 20;26(11):2389–430.

60. Berger M, Schmid M, Welchowski T, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Beyersmann J. Subdistribution hazard models for competing risks in discrete time. Biostatistics. 2020 Jul 1;21(3):449–66.

61. Morita K. Introduction to Survival Analysis in the Presence of Competing Risks. Ann Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Oct 1;3(4):97–100.

62. The Lancet Neurology. WHO launches its Global Action Plan for brain health. Lancet Neurol. 2022 Aug;21(8):671.

63. McCarthy EP, Chang CH, Tilton N, Kabeto MU, Langa KM, Bynum JPW. Validation of Claims Algorithms to Identify Alzheimer's Disease and Related Dementias. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2022 Jun 1;77(6):1261–71.

64. Chow EPF, Hsu B, Waite LM, Blyth FM, Handelsman DJ, Le Couteur et al. Diagnostic accuracy of linked administrative data for dementia diagnosis in community-dwelling older men in Australia. BMC Geriatr. 2022 Nov 15;22(1):858.

65. Harding Z, Wilkinson T, Stevenson A, Horrocks S, Ly A, Schnier C, et al. Identifying Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism cases using routinely collected healthcare data: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2019 Jan 31;14(1):e0198736.

66. Butt DA, Tu K, Young J, Green D, Wang M, Ivers N, et al. A validation study of administrative data algorithms to identify patients with Parkinsonism with prevalence and incidence trends. Neuroepidemiology. 2014;43(1):28–37.

67. Waller M, Mishra GD, Dobson AJ. A comparison of cause-specific and competing risk models to assess risk factors for dementia. Epidemiol Methods. 2020 Jan 28;9(1):20190036.

68. Rhew SH, Kravchenko J, Lyerly HK. Exposure to low-dose ambient fine particulate matter PM2.5 and Alzheimer's disease, non-Alzheimer's dementia, and Parkinson's disease in North Carolina. PLoS One. 2021 Jul 9;16(7):e0253253.

69. Cheng S, Jin Y, Dou Y, Zhao Y, Duan Y, Pei H, et al. Long-term particulate matter 2.5 exposure and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2022 Nov;212:33–41.

70. Mohammadzadeh M, Khoshakhlagh AH, Grafman J. Air pollution: a latent key driving force of dementia. BMC Public Health. 2024 Sep 2;24(1):2370.

71. Wainberg M, Andrews SJ, Tripathy SJ. Shared genetic risk loci between Alzheimer's disease and related dementias, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023 Jun 16;15(1):113.

72. Moskvina V, Harold D, Russo G, Vedernikov A, Sharma M, Saad Met, et al. Analysis of genome-wide association studies of Alzheimer disease and of Parkinson disease to determine if these 2 diseases share a common genetic risk. JAMA Neurol. 2013 Oct;70(10):1268–76.