Abstract

Background: Mental health disorders affect approximately 60% of patients in primary healthcare (PHC) settings, yet conditions like depression and anxiety often remain undiagnosed due to limited provider training. Saudi Arabia has progressively integrated mental health into PHC services, aligning with the WHO’s mhGAP Plan (2013–2030). This study examines these efforts and introduces the Five-Step Model (AlKhathami Approach) as a framework to enhance mental health care delivery.

Methods: This study reviews three stages of integration: early training programs (1995–1999), the pilot PMHC program in the Eastern Province (2003–2016), and nationwide implementation (2017–2022). Data from 1,406 PHC centers, covering 114,068 patients and 329,016 visits, were analyzed. Training initiatives targeted 8,981 providers, emphasizing the Five-Step Model and a Training of Trainers (TOT) strategy.

Results: By 2022, PMHC services were implemented in 75% of PHC centers, achieving a 77.2% improvement rate among patients and an 8% referral rate to psychiatric hospitals. Challenges such as workforce shortages, geographic barriers, and stigma were addressed through mobile training, community awareness, and technological investments.

Conclusion: Saudi Arabia’s phased integration demonstrates the effectiveness of structured models like the AlKhathami Approach in enhancing mental health services. These efforts position the country as a global leader in mental health integration, offering a scalable model for improving mental health care in PHC settings worldwide.

Keywords

Mental Health; primary healthcare services; Saudi Arabia; AlKhathami Approach

Introduction

Mental health issues affect a substantial portion of the patient population in primary health care (PHC) settings, constituting approximately 60% of cases (WHO/Wonca, 2008) [1]. These mental health disorders often complicate the management of chronic illnesses such as diabetes and hypertension [2]. Depression and anxiety, despite their prevalence, frequently go undiagnosed and untreated in PHC settings, primarily because of insufficient preparation by PHC physicians in managing these conditions effectively (WHO/Wonca, 2008) [1]. The economic impact of untreated mental health problems is significant, contributing to substantial financial losses for governments, employers, and households, resulting in a global productivity decline that costs the economy over $1 trillion annually [3]. Recent studies emphasize the urgent need to address mental health issues within PHC settings. For example, a 2021 WHO report highlights the critical role of PHC in mitigating the mental health burden, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, by integrating services into existing care frameworks [4]. Moreover, research conducted by AlKhathami et al. (2022) underscores the efficacy of structured patient interview approaches in enhancing the identification and treatment of mental health disorders in PHC centers in Saudi Arabia [5]. These advancements align with global calls to prioritize mental health care within PHC systems, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbates mental health challenges worldwide.

Integration Efforts in Saudi Arabia

In response to these challenges, Saudi Arabia has undertaken a series of initiatives to integrate mental health care into PHC services, guided by the WHO’s Alma-Ata Declaration of 1978 and the mhGAP Plan (2013–2030). This integration has evolved into three main stages since 1995:

Stage 1: Traditional model (1995–1999)

During the first stage of integration, the focus was on implementing psychiatric-based training programs for PHC doctors. These training sessions were conducted over three days and aimed at improving the knowledge and attitudes of PHC doctors regarding mental health issues. While these efforts were successful in enhancing theoretical understanding, they did not significantly improve the practical skills of physicians in managing mental health conditions [6].

Stage 2: Primary mental health program in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia (2003–2016)

The second stage involved piloting the Primary Mental Health Care (PMHC) program, which was based on Family Medicine concepts. This program was applied in PHC centers in the Eastern Province to develop a model for integrating mental health services into PHC. Over 13 years, the program established 11 PMHC clinics across three major cities, serving a total of 9,173 patients through 34,717 visits. The referral rate to psychiatric hospitals during this period was 5.4%. Furthermore, the program included 4,547 mental health education events. These efforts gained international recognition from organizations such as Wonca, EMRO, and WHO. In 2006, the WHO described the program as ‘the best practical model’ for integrating mental health into PHC settings. This success was also highlighted in the WHO/Wonca Report (2008) [1] and elaborated on by AlKhathami et al. [7].

Stage 3: Generalization of the PMHC program across Saudi Arabia (2017–2022)

The third stage focused on the nationwide implementation of the PMHC program. This stage aimed to document the Saudi Ministry of Health’s efforts in integrating PMHC as per the WHO’s mhGAP Plan (2013–2030) and leverage the Ministry’s experience to create a regional and global model. By September 2022, 1,406 out of 1,875 PHC centers (75%) across Saudi Arabia were providing PMHC services. These centers collectively served 114,068 patients through 329,016 visits, with an 8% referral rate to psychiatric hospitals. This stage also explored strategies for generalizing mental health care within PHC services while assessing the progress of implementing the WHO mhGAP Plan (2013–2030).

Contribution of the Current Study

Despite significant progress, research gaps remain regarding the scalability of mental health integration across diverse settings and the long-term impact on patient outcomes. This study builds upon the three stages of Saudi Arabia’s PMHC program by introducing the Five-Step Model (AlKhathami Approach) for patient interviews. This approach aims to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application, ensuring comprehensive mental health care within PHC settings. Additionally, the study aligns with recent global priorities by addressing the evolving mental health needs exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The outcomes of this study will contribute to the existing literature by:

- Providing updated evidence on the efficacy of structured patient interview models in PHC.

- Offering insights into strategies for scaling mental health integration within PHC systems.

- Highlighting the adaptability of the AlKhathami Approach to diverse PHC settings, thereby supporting the WHO’s mhGAP objectives for 2030.

This work also serves as a regional and global model for integrating mental health care into PHC, showcasing the potential of innovative training and service delivery strategies to enhance patient outcomes and overall health system performance.

Evidence before this study

The authors conducted a scoping review to evaluate existing literature on integrating mental health into PHC services in Saudi Arabia. Following PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews, the process included identifying relevant articles, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion in the final review. The PRISMA flow diagram is presented as a supplementary figure, and the checklist has been added as a supplementary file. Articles included in this review provided insights into the stages of mental health integration in Saudi Arabia, strategies employed, and outcomes achieved. The results of this scoping review are outlined in this study’s results section, where key findings from selected studies are discussed to establish the foundation for this research.

Report objectives

- Document the Ministry of Health’s efforts in integrating mental health into PHC services as a regional and global model.

- Explore strategies for generalizing mental health care within PHC services and assess the progress of implementing the WHO mhGAP Plan (2013–2030).

Training strategy

The training commenced with a Training of Trainers (TOT) approach, where regional organizers were selected from the target trainees.

Training subjects

- Mental health burden in PHC

- Patient interview approach using the Five-Step Model (AlKhathami Approach) [5]

- Collaboration between PHC and mental health care specialists, including the referral system

- An application trial was conducted in five regions. Following promising results, the training process was disseminated across all regions in Saudi Arabia.

Methodological enhancement

To ensure transparency and reproducibility of the study, the following methodological enhancements have been included:

Data collection tools

- Monthly surveys: Data on patient demography, visits, follow-up visits, service utilization, and outcomes were collected using standardized questionnaires tailored for PHC settings. The surveys were designed to capture patient demographics, mental health diagnoses, management strategies, and treatment outcomes.

- Monthly data reporting system: Regional organizers were responsible for collecting and submitting monthly aggregated data from PHC centers to a central database.

Statistical tests used - Descriptive statistics: Frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were calculated to summarize patient demographics, service utilization, and training outcomes.

- Trend analysis: Linear regression was employed to analyze the increase in the number of clinics, trained professionals, and patients served overtime.

Data validation

To ensure data reliability, a two-step validation process was implemented:

- Internal validation: Regional organizers cross-checked data before submission.

- Central validation: The central research team reviewed and validated the aggregated data, correcting any inconsistencies or errors.

Data collection and analysis

For the purpose of the study, Saudi Arabia was divided into 20 regions according to population density and geographical distance. Each region had an organizer responsible for arranging training and forming a team for monthly data collection. Data from January 2017 to September 2022 were collected to present the outcomes of Stage 3. The Excell program was used for data analysis and presentation.

Specific challenges faced during implementation

- Geographical barriers: The vast size and diverse geography of Saudi Arabia posed logistical challenges in reaching remote and underserved areas.

- Workforce shortages: Limited availability of trained mental health professionals, particularly in rural regions, hindered service delivery.

- Stigma: Cultural stigma surrounding mental health often prevented patients from seeking care and engaging with services.

- Technological gaps: Inconsistent access to digital tools and EHR systems across PHC centers created barriers to data collection and service coordination.

Solutions developed - Mobile training units: Introduced mobile teams to conduct training sessions and provide support in remote areas, reducing logistical constraints.

- Targeted recruitment and training: Focused on training local healthcare providers, including general practitioners and nurses, to bridge workforce gaps.

- Community awareness campaigns: Launched public education initiatives to reduce stigma and encourage help-seeking behaviors.

- Technological investments: Upgraded infrastructure and standardized EHR systems to ensure uniform data collection and improve communication between PHC centers.

Results

Physicians and PHC centers

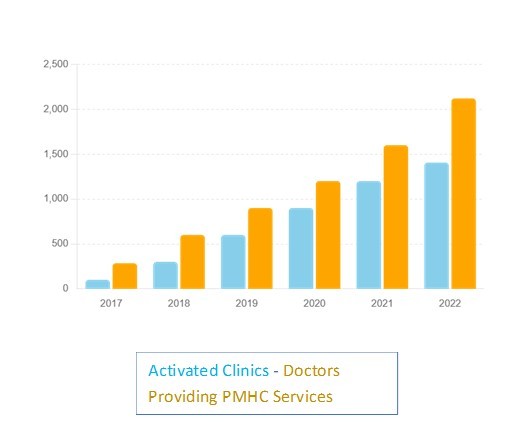

By the end of September 2022, a total of 2,121 physicians were actively providing PMHC as part of their daily work in Saudi Arabia. These physicians emerged from training courses targeting 2,940 PHC physicians, alongside 1,137 nurses, 32 psychologists, and 30 social workers. PMHC services were available in 1,406 (75%) out of 1,875 PHC centers in all regions of Saudi Arabia (Figures 1a and 1b).

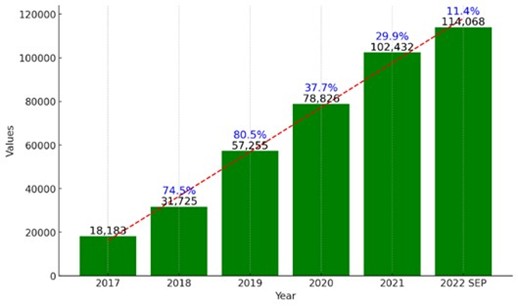

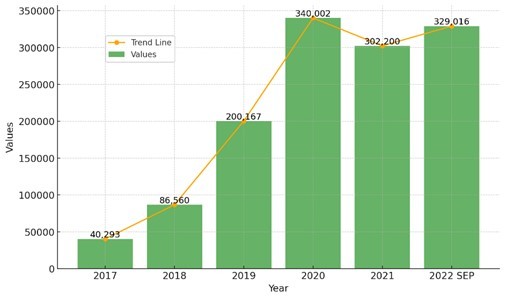

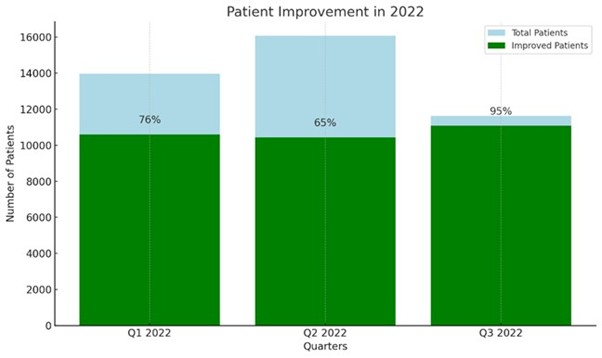

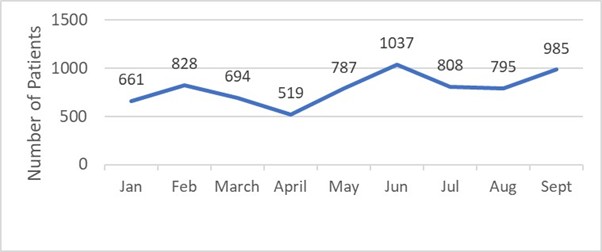

Training courses A total of 953 training courses were conducted to prepare PMHC providers. These courses targeted 8,981 PHC physicians and nurses, consisting of 70% general practitioners (GPs), 7% consultants, and 23% specialists, with 71% of the participants being Saudi nationals (Figure 2). Serviced patients and follow-up visits Between January 2017 and September 2022, PMHC providers successfully served 114,068 patients through 329,016 visits (Figures 3 and 4). Notably, female patients comprised 60% of the total population served. Age group distribution was with age ranged were 20% (18-25 years), 35% (26-40 years0, 30% (41-60 years), 15% (60+ years). Tables representing these age and gender distributions can be created for visual clarity in future presentations or reports. Management outcomes of 2022 During the first three quarters of 2022, a total of 32,124 patients, representing 77.2% of the 41,640 patients seen, showed improvement and responded well to the PMHC provider’s management of their mental health conditions. The improvement rates were as follows (Figure 5): - First quarter: 10,606 patients (76% improvement rate); second quarter: 10,438 patients (65% improvement rate); third quarter: 11,080 patients (95% improvement rate). Additionally, 7,114 patients (17%) were referred to psychiatric hospitals between January and September 2022 (Figure 6). Evidence before this study Before undertaking this study, the authors conducted an extensive review of existing literature and resources. The sources included databases such as PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar, as well as journal and book reference lists. The search criteria were broad, including studies published between 1995 and 2022, and were not limited to English language publications. The search terms used included "mental health integration," "primary health care," "Saudi Arabia," "mhGAP," and "Alma-Ata Declaration." There was a gap in the mental healthcare at the level of PHC centers’ services. Added value of this study This study provides a detailed account of the progressive efforts and achievements in integrating mental health care into PHC services in Saudi Arabia from 1995 to 2022. Unlike previous studies, this research offers a longitudinal perspective, documenting three distinct stages of integration and highlighting the strategies, outcomes, and lessons learned at each stage. The study showcases the effectiveness of the PMHC program in the Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia and its subsequent generalization across the country. It also emphasizes the innovative training strategies, such as the Training of Trainers (TOT) approach and the Five-Step Model (AlKhathami Approach), which have significantly improved the capacity of PHC providers to manage mental health issues. Implications of all the available evidence The findings of this study have several implications for practice, policy, and future research.

Discussion

The integration of PMHC services within Saudi Arabia’s PHC centers represents a significant milestone in the nation’s healthcare system. This widespread implementation has resulted in substantial progress, with PMHC services now being actively provided throughout the country. The continuous dedication to achieving the main goal reflects a coordinated effort to enhance mental health service capacity at the primary care level [8].

Workforce preparation and training impact

The implementation of regular training courses marks a significant step towards bolstering the PHC system’s ability to address mental health issues [9]. The broad reach of these training programs, which targets a diverse group of healthcare professionals, ensures a multidisciplinary approach essential for comprehensive patient management. This initiative aligns with Saudi Arabia’s broader goals of healthcare localization and sustainability, emphasizing the training of local professionals. This focus on Saudi nationals supports cultural relevance and fosters a stable workforce capable of addressing the unique mental health needs of the population [10,11]. Continuous training and professional development opportunities are necessary to keep healthcare providers updated on the latest advancements in mental health care [12]. General practitioners, who accounted for 70% of the trainees, are often the first point of contact in the healthcare system and play a pivotal role in the early detection and management of mental health conditions [13]. The inclusion of consultants and specialists ensures that more complex cases can be appropriately managed, and that robust support is provided for GPs [14].

Patient engagement and follow-up

The substantial number of patients utilizing mental health services demonstrates significant progress in service utilization [15]. This high level of patient interaction reflects the success of training initiatives, indicating that PHC providers are now more adept at identifying and managing mental health conditions [13]. However, the fact that 25% of PHC centers still do not offer these services underscores the need for continued efforts to achieve full coverage, particularly in rural and underserved areas.

During Stage 3 has seen significant engagement with mental health services at the primary care level. This is evidenced by the high number of visits, emphasizing the ongoing need for accessible mental health services [15]. Follow-up visits play a crucial role in monitoring treatment progress, adjusting therapeutic interventions, and providing continuous support [14]. The data indicate a robust follow-up system, suggesting that patients receive ongoing support that is essential for effective mental health management [16]. Good management outcomes further highlight the effectiveness of integrating mental health into primary care [15]. Regular follow-up visits are associated with better treatment adherence and improved mental health outcomes [17]. The high volume of follow-up visits reflects a commitment to sustained patient care [12].

Referral to psychiatric hospitals

Patients were referred to psychiatric hospitals, emphasizing the need for specialized care in certain cases [14]. This referral process is vital for managing severe psychiatric disorders or complex cases that exceed the capacity of PHC settings [16].

National healthcare strategy

These results align with national healthcare strategies aimed at integrating mental health into primary care. The Saudi Vision 2030 emphasizes the importance of accessible and comprehensive healthcare services, including mental health [11]. The data supports the notion that significant progress is being made towards these goals, as evidenced by the increasing number of patients receiving care and the extensive follow-up system in place.

Comparative analysis

To contextualize the findings of this study, a comparison was conducted with similar programs implemented in other regions. In Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) Countries, mental health integration programs exhibit similarities and differences compared to Saudi Arabia i.e. in Qatar, the Primary Healthcare Corporation has integrated mental health services focusing on early intervention and community-based care. Unlike Saudi Arabia’s widespread decentralization, Qatar utilizes centralized service hubs for mental health care. While effective, Qatar’s approach limits access to rural populations, a gap Saudi Arabia addresses through national coverage [18]. United Arab Emirates (UAE) prioritizes telemedicine for mental health alongside public awareness campaigns. Saudi Arabia’s emphasis on face-to-face PHC services complements UAE’s model by addressing cases requiring in-person consultation [19]. In Egypt, the General Secretariat for Psychiatry adopted the training of trainers on the Five-Step Approach, which was implemented by the Saudi Ministry of Health in 2018. Following its success in integrating mental health into primary healthcare centers across three provinces, the approach was subsequently generalized at the level of the Egyptian Ministry of Health, yielding positive and encouraging results [20]. It demonstrated similar outcomes to those achieved in Saudi Arabia, further supporting the potential success of the project if the modern approach is applied. Building on this success, training was conducted in several other countries, including Sudan, Oman, Dubai, Morocco, and Tunisia. This was followed by further initiatives to qualify trainers on this modern AlKhathami Approach in various other nations, such as Ukraine and Brazil. Where, South Africa integrates mental health into district health systems under resource constraints. Saudi Arabia’s robust funding and comprehensive training strategies demonstrate the impact of resource investment on program success [21].

WHO benchmark standards

- Accessibility: WHO recommends 80% mental health accessibility via PHC. Saudi Arabia achieves 75%, reflecting near-compliance with global benchmarks and an opportunity for further enhancement [22].

- Referral Pathways: With an 8% referral rate, Saudi Arabia aligns closely with WHO’s emphasis on empowering PHC providers to manage common mental health conditions, reducing dependency on specialized services [23].

Summary of findings

These comparative analyses position Saudi Arabia as a leader in mental health integration within PHC settings, offering valuable lessons for GCC and middle-income countries. Saudi Arabia demonstrates an effective balance between accessibility, resource utilization, and compliance with WHO benchmarks, underscoring the replicability and adaptability of its approach for varied healthcare contexts.

Conclusion

Saudi Arabia’s efforts to integrate mental health services into its PHC system reflect a strong commitment to improving mental health outcomes. The significant increase in trained professionals and widespread availability of PMHC services in PHC centers are key achievements. Addressing the remaining challenges, particularly in terms of service coverage and sustainability, will be crucial for continued success. With ongoing investment and innovation, Saudi Arabia can set a global benchmark for integrating mental health services within PHC systems.

Recommendations

Despite considerable progress in integrating PMHC services, challenges remain in ensuring its sustainability, which requires ongoing support and resources. Further efforts are needed to continue expanding and improving mental health services and addressing the service provision gaps in the remaining 25% of PHC centers [9]. This includes increasing the number of trained PHC providers, enhancing the quality of follow-up care, and using an effective and efficient patient interview approach such as the Five-Step Model (AlKhathami Approach). Any remaining barriers to accessing mental health services should also be addressed. Innovative solutions such as telehealth, telemedicine, and mobile health applications, can play a pivotal role in enhancing the reach and efficiency of follow-up visits, particularly in remote areas [13]. Robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms are needed to assess the effectiveness of PMHC services. Patient satisfaction and feedback should be regularly collected to ensure that the services provided meet the needs of the population. Future research should also focus on patient outcomes to assess the long-term impact of these services and identify areas for improvement [15]. Additionally, collaboration with international mental health organizations may provide valuable insights for further enhancement [24]. It is recommended to conduct a "Cost-Effectiveness Analysis" to evaluate the cost per patient treated, resource utilization metrics, and the overall economic impact.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this study. All authors have contributed significantly to the research and writing of this paper and agree with its content and conclusions.

Funding Source

No funding resources.

Ethical Considerations

This study reviewed and approved by a Saudi Institutional Review Board (IRB) committee. All data was handled confidentially, ensuring no disclosure of participants’ names, telephone numbers, and addresses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Saudi Ministry of Health for their support and collaboration throughout the stages of this study. Special thanks are extended to all the primary health care physicians, nurses, psychologists, and social workers who participated in the training programs and contributed to the successful implementation of the PMHC services.

We also acknowledge the valuable contributions of the regional organizers and data collectors who ensured the accuracy and completeness of the data. Additionally, we are grateful to the World Health Organization (WHO), the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO), and the World Organization of Family Doctors (Wonca) for their recognition and support of the PMHC program.

References

2. AlKhathami AD, Alamin MA, Alqahtani AM, Alsaeed WY, AlKhathami MA, Al-Dhafeeri AH. Depression and anxiety among hypertensive and diabetic primary health care patients. Could patients' perception of their diseases control be used as a screening tool? Saudi Med J. 2017 Jun;38(6):621-8.

3. World Bank. The economic impact of untreated mental health problems [online]. 2020. Available at: https://www.worldbank.org/ [Accessed 9 Jan. 2025].

4. WHO. Role of primary health care in mitigating the mental health burden. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021.

5. AlKhathami AD. An innovative 5-Step Patient Interview approach for integrating mental healthcare into primary care centre services: a validation study. Gen Psychiatr. 2022 Aug 24;35(4):e100693.

6. Al-Khathami AD, Mangoud AM, Rahim IA, Abumadini MS. Traditional mental health training's effect on primary care physicians in Saudi Arabia. Ment Health Fam Med. 2011 Mar;8(1):3-5.

7. Al-Khathami AD, Al-Harbi LS, AlSalehi SM, Al-Turki KA, AlZahrani MA, Alotaibi NA, et al. A primary mental health programme in Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, 2003-2013. Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2013 Dec 1;10(4):203-10.

8. Zivin K, Miller BF, Finke B, Bitton A, Payne P, Stowe EC, et al. Behavioral Health and the Comprehensive Primary Care (CPC) Initiative: findings from the 2014 CPC behavioral health survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017 Aug 29;17(1):612.

9. WHO. Integrating mental health into primary care: A global perspective. World Health Organization; 2020.

10. Mani ZA, Goniewicz K. Transforming Healthcare in Saudi Arabia: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Vision 2030’s Impact. Sustainability. 2024 Apr 15;16(8):3277.

11. Alshahrani S, Khan S. The cultural relevance and sustainability of mental health care in Saudi Arabia. Middle East J Psychiatry Alzheimers. 2019;10:221-9.

12. Martinez R. Continuous professional development in primary mental healthcare. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2023;43:56-64.

13. Johnson D, Brown E, Martinez R. Primary care and mental health integration: training and outcomes. Int J Integr Care. 2023;23:678-90.

14. Brown E. The role of consultants and specialists in integrated primary mental healthcare. Ment Health Fam Med 2021; 17: 145-52.

15. Smith KM, Scerpella D, Guo A, Hussain N, Colburn JL, Cotter VT, et al. Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Implementing a Multicomponent Intervention to Improve Communication With Older Adults With and Without Dementia (SHARING Choices) in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022 Jan-Dec;13:21501319221137251.

16. Albejaidi F, Nair KS. Building the health workforce: Saudi Arabia's challenges in achieving Vision 2030. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019 Oct;34(4):e1405-16.

17. Lee J, Martinez R, Triliva S. Evaluating the impact of mental health training on primary care practices. J Ment Health Train Educ Pract. 2022;17:312-24.

18. Primary Healthcare Corporation. Qatar’s Community-Based Mental Health Model. 2023. Accessed from: https://phcc.gov.qa.

19. UAE Ministry of Health. National Mental Health Strategy 2017-2021. Accessed from: https://mohap.gov.ae.

20. MHGAP implementation in Egypt “National scale / 2018”. General Secretariat of Mental Health & Addiction Treatment. Ministry of Health & Population. WHO – Egypt; 2019.

21. South African Department of Health. District Health System and Mental Health Integration. Cape Town; 2015.

22. WHO. mhGAP Intervention Guide for Mental, Neurological and Substance Use Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.

23. WHO. Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030. Geneva: WHO; 2013.

24. Triliva S, Simos G, Hatzinikolaou S. International perspectives on mental health training and integration. Glob Ment Health. 2020;7: e23.