Definitions

Psychological capacity

The mental and emotional resources that an individual can draw upon to manage stress, solve problems, and maintain well-being. It includes cognitive abilities, emotional strength, resilience, and coping mechanisms. When psychological capacity is overwhelmed by excessive stress or demands, it can lead to a decrease in mental health, known as psychological capacity compression [1].

Resilience

The ability to recover quickly from setbacks, adversity, or difficult situations. It involves mental toughness, adaptability, and the capacity to bounce back from stress or trauma [2].

Coping strategies

Techniques and methods that individuals use to manage stress, challenges, and difficult emotions. Coping strategies can be adaptive (e.g., problem-solving, seeking support) or maladaptive (e.g., avoidance, substance use) [3].

Emotional regulation

The process by which individuals influence their emotions, how they experience them, and how they express them. Effective emotional regulation helps maintain emotional balance and respond appropriately to different situations [4].

Self-efficacy

The belief in one’s own ability to successfully accomplish tasks and achieve goals. High self-efficacy leads to greater confidence in facing challenges, while low self-efficacy can result in avoidance and self-doubt [5].

Psychological Capacity Stress (Compression)

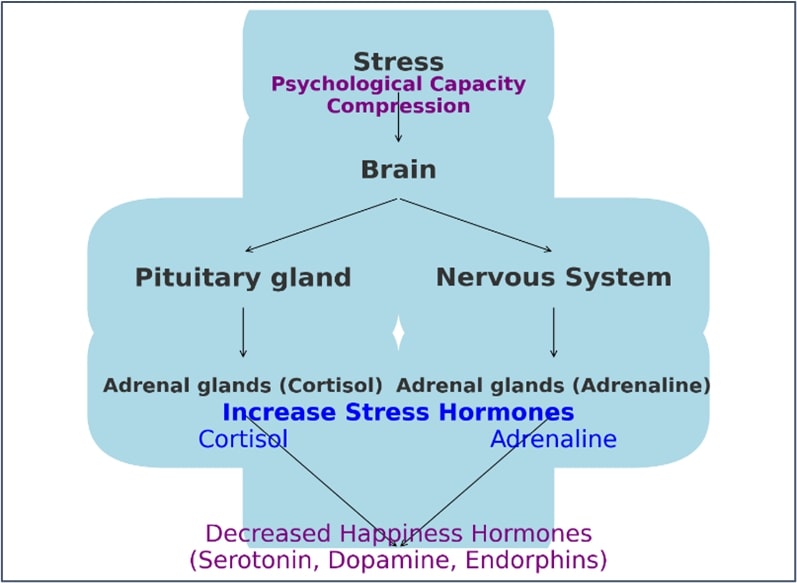

This term refers to the phenomenon where individuals experience reduced ability to manage stressors due to overwhelming demands on their psychological resources. This can result from chronic stress, burnout, or sustained high levels of anxiety. When psychological capacity is compressed, it can lead to dysregulation in the body's hormonal balance, particularly involving adrenaline, cortisol, and happiness hormones like serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins [6]. This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Psychological capacity Compression Impacts:

Adrenaline and cortisol

Adrenaline: Often referred to as the "fight or flight" hormone, adrenaline is released in response to acute stress. It prepares the body to react to immediate threats by increasing heart rate, expanding air passages in the lungs, and enlarging the pupils. Chronic stress, however, can lead to sustained high levels of adrenaline, which may result in cardiovascular problems, anxiety, and sleep disturbances [7].

Cortisol: Known as the "stress hormone," cortisol helps regulate metabolism, reduce inflammation, and control blood sugar levels. It is released in response to stress and low blood-glucose concentration. Chronic stress results in consistently high levels of cortisol, which can lead to various health issues such as hypertension, insulin resistance, immune system suppression, and mental health problems like depression and anxiety [8].

Decreased happiness hormones

Serotonin: This neurotransmitter contributes to feelings of well-being and happiness. Low levels of serotonin are associated with depression, anxiety, and mood disorders. Chronic stress can deplete serotonin levels, leading to increased feelings of sadness and irritability [9].

Dopamine: This neurotransmitter is involved in reward and pleasure systems in the brain. Low dopamine levels can result in reduced motivation, pleasure, and an increased risk of depression. Prolonged stress can diminish dopamine levels, impacting an individual's ability to experience joy and satisfaction [10].

Endorphins: These are natural painkillers produced by the body that also help promote a sense of well-being. Chronic stress can lower endorphin levels, contributing to feelings of pain, discomfort, and emotional distress [11].

Mechanisms linking psychological capacity compression to hormonal changes

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis: Chronic stress activates the HPA axis, leading to the sustained release of cortisol. Over time, this can disrupt the balance of other hormones, including adrenaline and happiness hormones. The HPA axis's overactivity can deplete resources needed for producing serotonin, dopamine, and endorphins [12].

Neuroplasticity: Chronic stress can negatively affect neuroplasticity, the brain's ability to adapt and change. This can result in structural and functional changes in brain regions involved in mood regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. These changes can impair the production and regulation of happiness hormones [13].

Inflammation: Chronic stress can lead to systemic inflammation, which has been linked to decreased levels of serotonin and dopamine. Inflammation can interfere with the synthesis of these neurotransmitters and contribute to mood disorders [14].

Behavioral changes: Psychological capacity compression often leads to unhealthy coping mechanisms, such as poor diet, lack of exercise, and substance abuse. These behaviors can further disrupt hormonal balance and exacerbate the effects of stress on the body and mind [15].

Cultural Considerations in Psychological Capacity Compression and Treatment

The expression of psychological distress varies across cultures. For instance, in collectivist cultures, stress may be managed through community and family support, which can buffer against psychological capacity compression [16]. Conversely, in cultures emphasizing individualism, people may feel pressured to manage stress alone, potentially increasing psychological burden. Additionally, some cultures may express psychological distress through physical symptoms, a phenomenon known as somatization [17].

Therefore, Clinicians must be culturally competent, understanding how cultural beliefs affect mental health and treatment preferences. This may involve collaborating with cultural mediators or integrating traditional practices into treatment plans to ensure they are culturally appropriate and effective.

Assessing Psychological Capacity Compression in Clinical Settings

Psychological capacity compression previously was assessed using a variety of methods in clinical settings. Key approaches include clinical interviews, self-report questionnaires such as the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) [18] and the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) [19], psychological assessments including the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck et al., 1996) and Heart Rate Variability (HRV) [20], and observational methods.

Now it is become feasible and practical effective approach using the “Stress Assessment Screening Step” (AlKhathami Approach Step-2). It has a high validity and reliability as compared to expert psychiatrists, PHQ-9, and GAD-7 questionnaires [21].

Factors Influencing Psychological Capacity Compression and Mental Health Outcomes

Psychological capacity compression and mental health outcomes are influenced by genetics, personality traits, and life experiences.

Genetics and psychological capacity compression

Genetic factors, such as variations in serotonin transporter genes, can increase susceptibility to stress, heightening the risk of psychological capacity compression [22].

Personality traits and stress resilience

Personality traits like neuroticism increase vulnerability to anxiety and depression, while traits like resilience and optimism protect psychological capacity [19].

Life experiences impact on stress and mental health

Adverse childhood experiences can lead to long-term changes in the brain’s stress response, increasing vulnerability to psychological capacity compression [23]. Positive life experiences can enhance psychological resilience [2].

Indicators and Signs of Psychological compression

When stress hormones like adrenaline and cortisol rise, and the levels of happiness hormones decrease due to psychological capacity compression, there are three key signs and three indicators of these changes in the body:

Indicators of psychological stress

Practical point: Assessing the Role of Psychological Stress in Patients

Consider the possibility of psychological stress contributing to a patient's problems if they:

- Suffer from an uncontrolled chronic disease or persistent physical symptoms

- Frequently seek healthcare assistance

- Experience difficulty sleeping

If any of these conditions are present, psychological stress may be a significant factor.

Signs of psychological stress

Sleep disturbances: Difficulty in falling asleep, staying asleep, or experiencing restful sleep, interrupted sleep [24].

Decline in performance and concentration: Reduced ability to focus, decreased productivity, and impaired cognitive functions [25].

Impact on Social Relationships: Increased irritability, easy anger, and a tendency to withdraw and prefer isolation [26].

These indicators reflect the body's response to heightened stress and the subsequent imbalance in hormone levels, affecting overall well-being and daily functioning.

Practical Point: Assessing Psychological Capacity

When you meet a patient or a person, assess their psychological capacity by asking the following questions:

1. Sleep:

o Are you experiencing any difficulties with sleep?

2. Performance and Concentration:

o Have you noticed any decline with your performance or concentration?

3. Relationship:

o Are there easy anger or prefer isolation?

If the answer to any of these questions is "yes," it indicates that the person might be suffering from psychological stress.

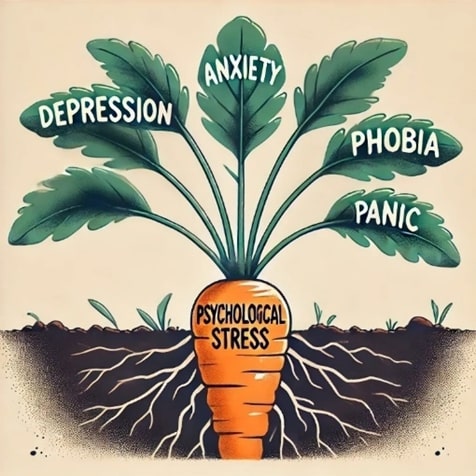

Root and Branches Theory (New Theory by AlKhathami Abdullah, 2024)

Empirical evidence

The "Root and Branches Theory" posits that psychological stress is a fundamental cause of various mental health disorders. Addressing this stress can alleviate symptoms and prevent recurrence. Empirical research supports this, showing that managing chronic stress through therapeutic interventions significantly reduces symptoms of anxiety, depression, and other disorders.

- Psychological stress and depression: Chronic stress is a key predictor of depression, overwhelming an individual’s psychological capacity and leading to mood dysregulation [27].

- Stress and anxiety disorders: Chronic stress is closely linked to anxiety disorders like generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder, and phobias. Stress alters neurochemical pathways, particularly in the HPA axis, contributing to anxiety [12].

- Obsession compulsive disorder (OCD) and stress: Stress exacerbates OCD symptoms by intensifying anxiety and compulsions. Effective stress management techniques, such as exposure and response prevention are crucial [28].

- Panic attacks and phobias: Chronic stress often triggers or worsens panic attacks and phobias by causing hyperarousal of the autonomic nervous system [29].

- Hormonal imbalance due to stress: Chronic stress disrupts the HPA axis, leading to elevated cortisol and adrenaline levels, which negatively impact mood regulation [8].

- Neuroplasticity and chronic stress: Chronic stress can lead to hippocampal atrophy, impairing cognitive function and increasing vulnerability to mood disorders [13].

Overall, addressing stress as a root cause is essential for alleviating symptoms and preventing the recurrence of these disorders.

Visual representation of the root and branches theory

Psychological capacity compression, driven by a decrease in happiness hormones and an increase in stress hormones (adrenaline and cortisol), can be visualized as the root of a tree, representing the fundamental cause of the problem. The symptoms that arise from this compression are represented by the branches of the tree, encompassing five key types of psychological distress: depression, various forms of anxiety, including obsessive-compulsive disorder, phobias, panic attacks, and generalized anxiety. These symptoms can differ widely among individuals, with some experiencing just one or two branches, while others may grapple with multiple.

The fact that these disorders are commonly managed with antidepressants lends credibility to the root and branch theory. This metaphor emphasizes the importance of holistic and root-focused approaches in mental health treatment, focusing on increasing happiness hormones and reducing stress hormones, rather than simply treating individual symptoms, as depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Visual Representation of the “Root and Branches Theory” in Psychological Capacity Compression.

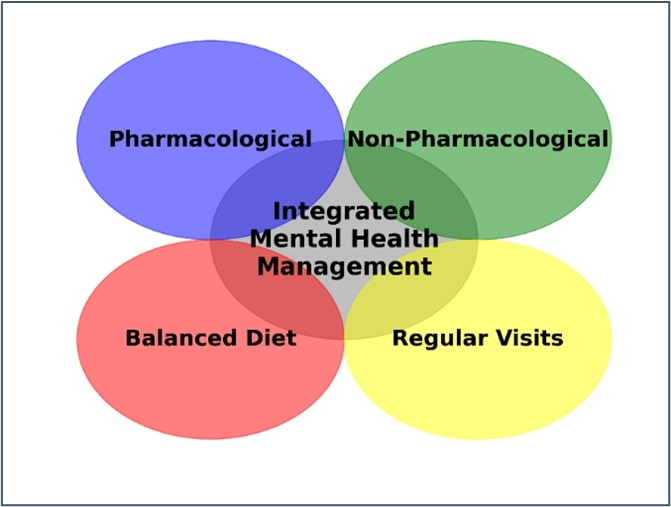

Integrated Mental Healthcare Management

Balanced approach

A balanced approach integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments is crucial for optimizing mental health outcomes while addressing individual patient needs and potential barriers. Combined treatment strategies often result in better health outcomes and improved quality of life [30]. Lifestyle interventions like regular physical activity and a balanced diet can mitigate the negative effects of stress on hormonal balance, improving mental health outcomes [31].

Combining pharmacological, non-pharmacological, nutritional, and regular visits can provide comprehensive and effective management for various health conditions. The synergy between these interventions often leads to better health outcomes compared to using a single approach [32]. Pharmacological treatments can offer immediate symptom relief, while non-pharmacological and nutritional strategies provide long-term benefits and help prevent recurrence [33]. This approach serves as a preventive measure, reducing the risk of developing chronic diseases, and can even lead to reducing or stopping medication [34].

Figure 3. A balanced approach.

A. Pharmacological management

Goal: To prevent the breakdown of happiness hormones.

- Antidepressants: SSRIs and SNRIs are first-line treatments for depression and anxiety, and commonly prescribed. It is used to manage emotional dysregulation, improve mood, motivation, and treat trauma-related disorders [35]. However, Pharmacological treatments like SSRIs are effective but may cause side effects such as sexual dysfunction and weight gain should be considered. Atypical antidepressants like bupropion are alternatives for patients who do not tolerate SSRIs or SNRIs.

B. Non-pharmacological management

Goal: To increase happiness hormones and lower stress hormones.

- Enhancing happiness hormones production: Engaging in regular activities such as walking, and encouraging hobbies and interests improve the mood status [27] Patient compliance is crucial, as severe depression or anxiety can hinder adherence to lifestyle interventions [36].

- Preventing breakdown of happiness hormones: Avoiding harmful arguments and self-blame by focusing on positive ownership of things.

- Lowering stress hormones: Implementing relaxation therapies such as deep breathing exercises.

- Conflict resolution & problem-solving skills: Using techniques such as narrative therapy to resolve interpersonal conflicts and solve problems.

C. Balanced diet

Goal: To support happiness hormones production.

- Consuming fruits, vegetables, healthy fats, vitaminsB1, B6 and B12, vitamin D (1,000-2,000 IU daily) particularly for those with low sunlight exposure, folic acid, and magnesium (200-400 mg/day) support brain health and reduce anxiety [37]. Omega-3 Fatty Acids 1,000-2,000 mg daily to reduce inflammation and improve mood [38].

D. Regular doctor visits

It contributes to:

- Consistent case monitoring: Ensuring conditions are monitored and managed effectively to reduce the risk of complications [30].

- Medication management: Adjusting medications based on the patient’s current health status and response to treatment for optimal therapeutic outcomes.

- Lifestyle recommendations: Providing tailored advice on diet, exercise, and other lifestyle factors that contribute to overall well-being, helping patients make informed decisions about their health.

- Mental health support: Offering opportunities for patients to discuss mental health concerns, receive support, and get referrals to mental health specialists if needed.

- Building a Doctor-Patient Relationship

- Trust and communication: Regular visits help build a trusting relationship between the patient and the doctor, facilitating open communication and a better understanding of the patient’s health needs.

D. Collaboration with mental health specialists

Mental health professionals may collaborate to provide holistic care, particularly in cases where mental health and social factors intersect.

- Psychiatrist: if case is suspected to have psychotic element, suicidal, drug abuse, postpartum depression, child psychotic disorder, or resistant should involve psychiatrist in the diagnosis and management plan (AlKhathami Approach, Step-3).

- Psychologist: primarily focuses on assessing, diagnosing, and treating mental health issues through therapeutic interventions such as psychotherapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy, and counselling. They often work with individuals to understand their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, providing strategies to manage mental health challenges and improve overall well-being. Thus, Family doctor should collaborate with psychologist to provide specific psychological therapy as needed for the patient.

- Social worker: A social worker focuses on helping individuals, families, and communities improve their well-being by addressing social, economic, and environmental factors that impact their lives. They provide support, advocacy, and resources to help person navigate challenges such as poverty, addiction, domestic violence, and mental health issues. Social workers often connect person with community resources and work to improve social systems and policies.

Practical Point:

First Visit: Apply the 5-Step Approach. If necessary, initiate management, which may include pharmacological interventions, non-pharmacological treatments, and nutritional supplements such as magnesium, vitamins B1, B6, B12, and vitamin D (if needed).

Second Visit (after 2 weeks): Assess the improvement of the patient's usual symptoms. Conduct a reassessment and provide supportive therapy. Introduce narrative therapy to enhance problem-solving skills. Continue with the established management plan.

Third Visit (after 3 weeks): Significant improvement or remission is typically observed, although conditions like panic disorder or social phobia may require more time and higher doses. Adjust the dosage if there is no remission.

Follow-up Visits: Schedule follow-up appointments every 3-4 weeks until remission is achieved. Once remission is stable, extend the interval between visits to every two months, continuing this schedule for nine months. After maintaining remission, gradually taper the medication dosage over time until it can be safely discontinued.

Comorbidities management

Managing patients with coexisting mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety, alongside chronic physical illnesses like diabetes or cardiovascular disease, requires a customized, integrated approach that addresses the complexities of both mental and physical health. Pharmacological treatments must be carefully chosen to manage both the mental health disorder and the chronic physical condition, with attention to avoiding adverse interactions.

In patients with chronic physical diseases, effective stress management that reduces stress hormones often leads to significant improvements in controlling the physical condition. Therefore, it is essential to regularly review and adjust the treatment plan for physical disease, including medication dosages, as needed. Collaborative care models, which involve a multidisciplinary team including primary care providers and specialists, are particularly effective in managing these dual conditions.

Personalized lifestyle changes are crucial for managing both mental health and chronic physical illnesses. For example, a tailored exercise program for a patient with depression and cardiovascular disease can improve both mood and cardiovascular health [39]. Nutritional counselling, such as adopting a Mediterranean diet, can support both mental health and chronic illness management [40].

Regular follow-up is essential to monitor progress and adjust treatment plans. This includes assessing mental health outcomes and physical health metrics, ensuring that any emerging issues are addressed promptly. Educating patients about the interconnectedness of mental and physical health empowers them to manage their conditions actively.

References

2. Masten AS. Resilience in development. In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ, eds. Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2002; pp.74-88.

3. Lazarus RS. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Publishing Company. 1984.

4. Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Review of general psychology. 1998 Sep;2(3):271-99.

5. Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company; 1997.

6. McEwen BS. Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. Eur J Pharmacol. 2008 Apr 7;583(2-3):174-85.

7. Goldstein DS. Adrenaline and the inner world: an introduction to scientific integrative medicine. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2010;95(5):2211-2.

8. Sapolsky RM. Why zebras don't get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping. 3rd ed. New York: Holt Paperbacks; 2004.

9. Carhart-Harris RL, Nutt DJ. Serotonin and brain function: a tale of two receptors. J Psychopharmacol. 2017 Sep;31(9):1091-120.

10. Grace AA. Dysregulation of the dopamine system in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia and depression. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 Aug;17(8):524-32.

11. Stein DJ. Neurobiology of the obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2000 Feb 15;47(4):296-304.

12. Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, et al. Regulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenocortical Stress Response. Compr Physiol. 2016 Mar 15;6(2):603-21.

13. McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Stress- and allostasis-induced brain plasticity. Annu Rev Med. 2011;62:431-45.

14. Dantzer R, O'Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008 Jan;9(1):46-56.

15. Kemeny ME. The psychobiology of stress. Current directions in psychological science. 2003 Aug;12(4):124-9.

16. Kim HS, Sherman DK, Taylor SE. Culture and social support. Am Psychol. 2008 Sep;63(6):518-26.

17. Kirmayer LJ, Young A. Culture and somatization: clinical, epidemiological, and ethnographic perspectives. Psychosom Med. 1998 Jul-Aug;60(4):420-30.

18. Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983 Dec;24(4):385-96.

19. Connor KM, Davidson JR. Development of a new resilience scale: the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety. 2003;18(2):76-82.

20. Thayer JF, Ahs F, Fredrikson M, Sollers JJ 3rd, Wager TD. A meta-analysis of heart rate variability and neuroimaging studies: implications for heart rate variability as a marker of stress and health. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012 Feb;36(2):747-56.

21. AlKhathami AD. An innovative 5-Step Patient Interview approach for integrating mental healthcare into primary care centre services: a validation study. Gen Psychiatr. 2022 Aug 24;35(4):e100693.

22. Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003 Jul 18;301(5631):386-9.

23. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998 May;14(4):245-58.

24. Smith A. Sleep Disorders in Mental Health: A Practical Guide for Psychiatrists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2018.

25. Jones R. Attention: A cognitive approach. 3rd ed. London: Routledge; 2019.

26. Brown GW, Green R. The Anatomy of Bereavement. London: Routledge; 2020.

27. Hammen C. Stress and depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293-319.

28. Abramowitz JS, Taylor S, McKay D. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 2009 Aug 8;374(9688):491-9.

29. Barlow DH. Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford PressBeck; 2004 Jan 28.

30. Boyd CM, Darer J, Boult C, Fried LP, Boult L, Wu AW. Clinical practice guidelines and quality of care for older patients with multiple comorbid diseases: implications for pay for performance. JAMA. 2005 Aug 10;294(6):716-24.

31. Martinsen EW. Physical activity in the prevention and treatment of anxiety and depression. Nord J Psychiatry. 2008;62 Suppl 47:25-9.

32. Brandt C, Böhner H, Blankenstein N, Joos S, Brenk-Franz K. Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapeutic interventions in patients with somatoform disorders: Recommendations for a stepped care approach in primary care. Molecular Psychiatry. 2010;15(12):1232-7.

33. Muth C, van den Akker M, Blom JW, Mallen CD, Rochon J, Schellevis FG, et al. The Ariadne principles: how to handle multimorbidity in primary care consultations. BMC Med. 2014 Dec 8;12:223.

34. Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Østbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health. 2003 Apr;93(4):635-41.

35. Van der Kolk B. The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Penguin Books. 2014.

36. Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007 Apr;27(3):318-26.

37. Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The Effects of Magnesium Supplementation on Subjective Anxiety and Stress-A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2017 Apr 26;9(5):429.

38. Grosso G, Galvano F, Marventano S, Malaguarnera M, Bucolo C, Drago F, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: scientific evidence and biological mechanisms. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014:313570.

39. Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, O'Connor C, Keteyian S, Landzberg J, Howlett J, et al. Effects of exercise training on depressive symptoms in patients with chronic heart failure: the HF-ACTION randomized trial. JAMA. 2012 Aug 1;308(5):465-74.

40. Jacka FN, O'Neil A, Opie R, Itsiopoulos C, Cotton S, Mohebbi M, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the 'SMILES' trial). BMC Med. 2017 Jan 30;15(1):23.