Abstract

Selective antibody deficiency syndrome (SAD), is a primary immunodeficiency in which immunoglobulin levels remain normal, but there is a reduced response to polysaccharide antigens after vaccination. SAD is recognized by the International Union of Immunology Societies as a primary immunodeficiency of unknown genetic cause. Patients with SAD are highly susceptible to severe respiratory tract infections with encapsulated bacteria. The infections found in SAD are similar to other antibody deficiencies; patients often present with recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections, otitis media, and sinusitis. The treatment of this pathology is based on preventing recurrent infections by known microorganisms, and in the case of serious infections, the use of intravenous or subcutaneous immunoglobulin.

Keywords

Specific antibody deficiency, Chronic rhinosinusitis, Immune deficiency, Immunoglobulin replacement therapy, Pneumococcal antibody concentration.

Introduction

Primary humoral immunodeficiencies can be caused by a wide number of genetic disorders, which have increased as their study continues. These include specific antibody deficiency syndrome against polysaccharides (SAD).

SAD, also known as selective antibody deficiency syndrome, is a primary immunodeficiency in which immunoglobulin levels remain normal, but there is a reduced response to polysaccharide antigens after vaccination [1]. This is secondary to alterations that include B cell development and functioning, even affecting their interaction with T lymphocytes.

The disease was first described during the 1980s [2], presenting as a lack of response against the polysaccharide antigens of Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Haemophilus influenzae type b [3].

Patients diagnosed with this type of immunodeficiency present alterations in the development and maturation of B cells and their formation of germinal centers. Although the possible causes are quite clear, secondary causes that can cause an immunosuppressive effect (including the use of drugs) must be ruled out [4]; since the diagnosis must not only be based on results of laboratory studies but must also be related to the clinical manifestations that will be described later.

These patients may have a diagnosis delay of years despite the frequency of infections and also have a risk of having structural complications due to the same infections [5]. Generally, their diagnosis is made after 2 years of age, when they already have an adequate response mediated by antibodies [6].

The prevalence of this syndrome in children with recurrent respiratory infections is highly variable, whose figures will depend on the source of information reviewed, with a percentage of 5 to 15% being common in the general population [7].

There are multiple pathogenic mechanisms related to SAD due to the great variety of immunological phenotypes, remembering that the development of antibodies against polysaccharides, whether conjugated or purified, is carried out by different cellular pathways, and the affectation can be in any of these pathways [8].

Regardless of the alterations that cause this pathology, the cellular inability to produce specific antibodies against microorganisms represents a high impact on the morbidity and mortality of individuals with this deficiency [9,10].

Clinical Diagnosis

Recurrent respiratory tract infections are the main clinical manifestation of specific antibody deficiency. The main pathogens involved are Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, which underlines the importance of antibodies in eliminating these encapsulated bacteria. Severe infections can lead to systemic complications such as sepsis and meningitis. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the leading cause of community-acquired pneumonia, otitis media, and sinusitis. However, it can also cause invasive diseases such as bacteremia, meningitis, and septic arthritis. These bacteria are generally grouped into gram-positive diplococci and are encapsulated, these capsular polysaccharides being an important virulence factor and basis for their classification by serotypes [11].

The most useful method to demonstrate recurrent ARS is nasal endoscopy. While the patient has symptoms where erythema, swelling, crusting, and purulent neutrophilic exudate emerging from the sinus ostia can be observed, sinus cultures obtained by endoscopy should present the development of pyogenic organisms typically present in humoral immunodeficiencies [4,12].

Haemophilus influenzae is a microorganism that causes invasive and non-invasive diseases, commonly classified into encapsulated and non-encapsulated types. H. influenzae type B is the encapsulated serotype that most frequently affects children and immunocompromised people. Its virulence factors include a capsule that hinders phagocytosis and protein H, along with cell adhesion molecules. All serotypes, especially type B, are common in lower respiratory tract infections such as pneumonia, as well as other serious infections such as meningitis, epiglottitis, cellulitis, septic arthritis, empyema, and bacteremia. H. influenzae commonly colonizes the human upper respiratory tract and, to a lesser extent, the conjunctiva and genital tract. Transmission occurs through respiratory droplets or contact with respiratory secretions. Furthermore, its role as an agent of broncho-aspiration pneumonia has been studied [13].

Variations in the diagnostic criteria for SAD versus CVID exist between the European Society of Immunodeficiency (ESID) criteria, American parameters, and the International Consensus Document for CVID. However, these papers agree that patients with CVID present low levels of IgG, IgA, and IgM, while patients with SAD present normal levels of these antibodies [5]. SAD is generally less severe than CVID and the clinical features do not completely fit either definition [6].

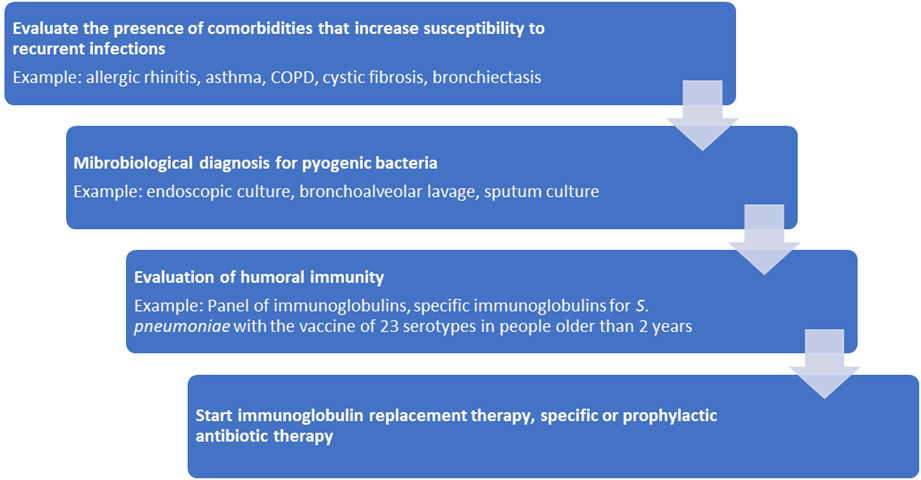

A diagnostic algorithm for SAD is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Approach to the patient with SAD (modified from Lawrence et al.) COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease.

Humoral Response to Pneumococcal Vaccine

The pneumococcal vaccine is used to assess the functional response of antibodies to the recurrence of sinopulmonary infections. It is a relevant tool for the evaluation of antibody immunodeficiencies, and it is also described in different combined type defects, so detecting an alteration in their response supports the diagnosis of immunodeficiencies.

Evaluation for polysaccharide defects with pneumococcal vaccine is performed from 2 years of age. It is important to mention that young children may respond to the non-conjugate vaccine; for example, a study of 56 children who were vaccinated at 12 months described a significant response to 23-PPV (Pneumococcal Polysaccharide Vaccine) unconjugated pneumococcus for 2 serotypes (4 and 8) in 71% of patients [20]. Another similar study describes the response to 78% of the serotypes (18 of the 23) 2 weeks after administration in 12-month-old children [10]. Although these studies are interesting and could serve as support for the evaluation of special cases, the study is currently accepted to assess responses from 24 months of age [14].

The production of antibodies must be measured individually for each of the serotypes included in the 23-PPV vaccine and the previous application of vaccines with conjugated serotypes such as 13-PCV (Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine) must be taken into account, so it is necessary to know what each of the vaccines includes (Table 1).

|

Serotype |

23-PPV |

13-PCV |

|

1 |

|

x |

|

2 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

x |

|

4 |

|

x |

|

5 |

|

x |

|

6A |

x |

x |

|

6B |

X |

x |

|

7F |

X |

x |

|

8 |

X |

|

|

9N |

X |

|

|

9V |

X |

x |

|

10 A |

X |

|

|

11 A |

X |

|

|

12F |

X |

|

|

14 |

X |

x |

|

15B |

X |

|

|

17F |

X |

|

|

18C |

X |

x |

|

19A |

X |

x |

|

19F |

X |

x |

|

20 |

X |

|

|

22F |

X |

|

|

23f |

X |

x |

|

33 |

X |

|

When conjugate vaccines have been applied recently, we will take into account the serotypes that are not found in said vaccine to evaluate the response to polysaccharides.

It is relevant for an adequate interpretation of the result to take into account the time in which the post-vaccination response is measured. IgG (immunoglobulin G) will be measured before administration; the vaccine is applied and at least 4 weeks must be waited for the second measurement. There is a window of 4 to 8 weeks with adequate security, but one should not wait too long between the vaccine and the post-vaccination measure since, for example, if a few months were allowed to pass, the results would not be valid, since over time they could decrease the concentrations and have a wrong interpretation.

Third-generation ELISA is usually used for analysis in the laboratory, but there are also multiplex studies (Luminex technology) to quantify serotypes [15]. The evaluation will be made taking into account the previous vaccination history for the interpretation. A concentration of 1.3 mcg/ml or more is accepted as an immunocompetent response and this measurement must be carried out for various serotypes, not just one. It would be ideal to measure all 23 serotypes. Currently, the suggestion is to measure at least 14, and the minimum that should be measured is 6 [16].

It is equally important that both samples are processed in the same laboratory and with the same method. Differences can be found in different commercial laboratories, referring, for example, to a study that compared levels of the same sample in 2 laboratories, a discrepancy in 31% of the samples [17]. It should be clinically correlated and, if necessary, repeat the measurements.

A response is considered adequate if the IgG is ≥1.3 mcg/ml or if the basal antibody concentration is increased by at least 4 times. The appropriate response rate depends on age [18]. Table 2 shows the expected response rate by age.

|

Age |

Percentage of serotypes with response |

|

2-5 years |

>50% |

|

6-65 years |

>70% |

Previously, other authors considered the levels of mcg/ml to stratify the response level: less than 0.3 mcg/ml is an absent response, 0.3-0.6 mcg/ml a low response, 0.61 to 1.2 mcg/ml intermediate, and greater than 1.21 mcg/ml normal response [19].

The degree of "non-response" in patients with SAD can be assessed in 4 phenotypes according to the consensus of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology:

A) Memory phenotype: Initial response to the 23 serotypes adequate, but they lose the response at 6 months.

B) Low response: They do not generate the protective level or do not increase the concentration twice.

C) Moderate Phenotype: They do not generate a protective level, but at least have 3 or more serotypes with levels of 1.3.

D) Severe: They do not generate protective levels or have only 2 or less with 1.3 mcg/ml.

There will be patients who have some protective pre-vaccination titers of 1.3 mcg/ml or more, in these cases a response is considered with an increase of 2 times the basal concentration level; however, a protective level is not definite [18].

Currently, the antibody function is not measured; there are no routinely available studies that measure antibody avidity and opsonophagocytic activity, in the future, this may give greater precision in the evaluation of polysaccharide defects [3].

Treatment and Prophylaxis

The treatment of this pathology is based on preventing recurrent infections by known microorganisms, and in the case of serious infections, the use of intravenous or subcutaneous immunoglobulin. Next, we will review the therapeutic options that have been used throughout the years, although there is a lack of scientific evidence for a standardized treatment.

The treatment recommendations are based mainly on the degree of involvement of the patient (mild, moderate, and severe), based on the levels of antibodies detected at the time of diagnosis, this has been discussed previously.

The use of immunoglobulin G as replacement therapy has been beneficial for some patients, especially if they do not respond to medical treatment and have pyogenic infections. Treatment is recommended for 1 to 2 years every 4 to 6 months, with doses of 0.4-06 g/ kg/month [1,2,20].

There is no consensus on the use of antibiotics, however, they are frequently used in clinical practice and selected patients. Sorensen et al. recommend that the use of antibiotics should be for patients who continue to have sinopulmonary infections despite preventive measures, especially at times of the year such as winter. The recommendations of The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) and the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (ACAAI) are general for primary immunodeficiencies; the use of azithromycin 500 mg a week or 250 mg every 48 h is recommended in adults and for children doses of 10 mg/kg a week or 5 mg/kg every 48 h, another option is TMP-SMX at a dose of 160 mg daily or every 12 h in adults and, dose of 5 mg/kg daily or every 12 h in children [2,6].

The recommendation regarding pneumococcal vaccines is that unvaccinated patients should receive the PCV vaccine followed by PPV, the latter in those over 2 years of age [6].

Conclusions

Despite being an infrequent pathology, it is necessary to identify the signs and symptoms that suggest this pathology in individuals older than 2 years of age. The use of conjugate and polysaccharide vaccines is an important and necessary part of establishing a definitive diagnosis. Vaccination with polysaccharide vaccines is necessary in the population at risk of suffering from infections by encapsulated microorganisms and in patients who cannot produce specific antibodies, it is necessary to evaluate the need for prophylaxis.

References

2. French MA, Harrison G. Systemic antibody deficiency in patients without serum immunoglobulin deficiency or with selective IgA deficiency. Clin Exp Immunol.1984;56(1):18-22.

3. Bonilla FA, Khan DA, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, Frank MM, Hsu JT, et al. Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters, representing the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; and the Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. Practice parameter for the diagnosis and management of primary immunodeficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(5):1186-205.e1-78.

4. Lawrence MG, Borish L. Specific antibody deficiency: pearls and pitfalls for diagnosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;129(5):572-8.

5. Janssen LMA, Reijnen ICGM, Milito C, Edgar D, Chapel H, de Vries E; unPAD consortium. Protocol for the unclassified primary antibody deficiency (unPAD) study: Characterization and classification of patients using the ESID online Registry. PLoS One. 2022;17(3):e0266083.

6. Sorensen RU. A Critical View of Specific Antibody Deficiencies. Front Immunol. 2019;10:986.

7. Boyle RJ, Le C, Balloch A, Tang ML. The clinical syndrome of specific antibody deficiency in children. Clin Exp Immunol. 2006;146(3):486-92.

8. Pletz MW, Maus U, Krug N, Welte T, Lode H. Pneumococcal vaccines: mechanism of action, impact on epidemiology and adaption of the species. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;32(3):199-206.

9. Sorensen RU, Edgar D. Specific Antibody Deficiencies in Clinical Practice. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(3):801-8.

10. Balloch A, Licciardi PV, Russell FM, Mulholland EK, Tang ML. Infants aged 12 months can mount adequate serotype-specific IgG responses to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126(2):395-7.

11. Perez EE, Ballow M. Diagnosis and management of Specific Antibody Deficiency. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2020;40(3):499-510.

12. Kashani S, Carr TF, Grammer LC, Schleimer RP, Hulse KE, Kato A, et al. Clinical characteristics of adults with chronic rhinosinusitis and specific antibody deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 ;3(2):236-42.

13. Slack MPE. A review of the role of Haemophilus influenzae in community-acquired pneumonia. Pneumonia (Nathan). 2015;1(6):26-43.

14. Licciardi PV, Balloch A, Russell FM, Burton RL, Lin J, Nahm MH, et al. Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at 12 months of age produces functional immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(3):794-800.e2.

15. Elberse KE, Tcherniaeva I, Berbers GA, Schouls LM. Optimization and application of a multiplex bead-based assay to quantify serotype-specific IgG against Streptococcus pneumoniae polysaccharides: response to the booster vaccine after immunization with the pneumococcal 7-valent conjugate vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2010;17(4):674-82.

16. U. R, Harvey T, E. L. Selective Antibody Deficiency with Normal Immunoglobulins [Internet]. Immunodeficiency. InTech; 2012.

17. Hajjar J, Al-Kaabi A, Kutac C, Dunn J, Shearer WT, Orange JS. Questioning the accuracy of currently available pneumococcal antibody testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(4):1358-60.

18. Orange JS, Ballow M, Stiehm ER, Ballas ZK, Chinen J, De La Morena M, et al. Use and interpretation of diagnostic vaccination in primary immunodeficiency: a working group report of the Basic and Clinical Immunology Interest Section of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(3 Suppl):S1-24.

19. Ferreyra PN, Nagao AT, Costa-Carvalho B, Carneiro-Sampaio MM. Síndrome de deficiencia de anticuerpos antipolisacáridos con niveles séricos normales de inmunoglobulinas / Syndrome of anti-polysaccharide antibodies deficiency with normal levels of immunoglobulins. Arch Alerg Inmunol Clin. 2001; 32(4):109-16.

20. Guidelines for Immunoglobulin Use. 3rd ed. UK: Department of Health (2021). Available from: https://www.nppeag.scot.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Scottish_IVIG_guidelines_2021_Final-Version.pdf