Abstract

Using CRISPR gene-editing technology, researchers have generated a live attenuated centrin gene deleted Leishmania major parasites (LmCen-/-) which are able to protect against visceral leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania donovani parasite. Since LmCen-/- vaccine is antibiotic resistant marker free, safe and prevents mortality, scientists are planning to use it in Phase I human clinical trials.

Keywords

Leishmania, Live attenuated Vaccine, centrin gene, Clinical trial, CRISPR

Commentary

Leishmaniasis, is a neglected parasitic disease, transmitted by the bites of Leishmania-infected female sand flies, affecting millions of peoples in 98 countries worldwide. According to clinical manifestation, leishmaniasis is broadly classified as tegumentary leishmaniasis (comprises of localized-cutaneous, diffuse-cutaneous and mucosal forms) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL; affecting liver, spleen, lymph nodes and bone marrow) which is most fatal and systemic, if left untreated. Depending on geographic distribution of species, VL is anthroponotic in South Asia and East Africa, caused by L. donovani, whereas the disease is zoonotic in the Central and South America, caused by L. infantum and/or L. chagasi [1-3]. More than ninety percent of VL cases occur in six countries, namely India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sudan, Ethiopia and Brazil [4].

Current treatment against any form of leishmaniasis is mostly dependent on available drugs like, pentavalent antimonials, amphotericin B, paromomycin, and miltefosine. However, these drugs are expensive, have prolong treatment duration, severe side effects and often leading to drug resistance in humans [5-8], suggested vaccine would be the best alternative of drug therapy. Recovery from primary infection including VL develop lifelong immunity against subsequent infection, suggesting that a vaccine is feasible [8-10] and also the most cost-effective ways to eliminate the disease than vector control and treatment strategies. According to a computer modelling study, a vaccine with a minimum 50% efficacy and as little as 5 years’ duration of protection, would be more cost-effective than the current available chemotherapies for both Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) and Visceral leishmaniasis (VL)- signify its importance for low- and middle- income countries (LMIC) [11,12]. This suggest the need for a pan Leishmania vaccine which would be effective against all form of leishmaniasis around the globe. Over the past decades, several strategies have been applied to develop a vaccine against various species of Leishmania. However, currently there is no licensed human vaccine available for any form of leishmaniasis.

Catering to develop this unmet need of a safe and effective vaccine, Dr. HL Nakhasi group initially developed centrin gene deleted live attenuated L. donovani parasites which was protective against L. donovani challenge in various preclinical animal models of VL [13-15]. Centrin is a calcium-binding cytoskeletal protein involved in the duplication of centrosomes in higher eukaryotes including Leishmania [16]. To overcome the regulatory barrier of using a visceral strain as a vaccine candidate, researchers applied modernize approach of CRISPR technology to develop centrin gene deleted live-attenuated vaccine from demotropic L. major strain (LmCen-/-) for the most effective century-old Leishmanization (LZ) practice where live parasite was used for human inoculation, leading to self-healing lesions and subsequent life-long immunity against future cutaneous infection [9,16-18]. Importantly, using CRISPR, generation of antibiotic resistance marker free LmCen-/- makes it compliant for human vaccine trials. In the murine model, researchers have shown that LmCen-/- is safe, immunogenic and induces robust host protection against sand fly transmitted cutaneous infection [16].

In the study by Karmakar S et al., researchers have taken an important step forward in defining the protective efficacy of dermotropic LmCen-/- vaccine against VL [19] which was supported by epidemiological evidence where pre-exposure to wild-type L. major parasites confer cross-protection against VL in various animal models and humans [20-22]. They have confirmed that the mutant parasite is safe and did not cause any signs of disease pathology even in immune-suppressed animals. Furthermore, they have explained that no viable LmCen-/- parasite were recovered from immunized animals even though they persist in sub-clinical condition for long enough to generate acquired immunity against future infection. However, the major concern of using live attenuated parasites as vaccine is the probability of reversion to virulent form. Test in sand flies through xenodiagnoses, possible source of genetic exchange with wild type parasites to regain virulence [23] and in various immune deficient animal models [16] including immune-suppressed hamsters [19], they have confirmed that the mutant parasites didn’t revert back to wild type form, so safe as vaccine candidate for human trial.

In this study, they have used hamsters as the gold standard animal model for VL, because of its similarity to humans in regard to disease symptoms, pathogenesis and immune responses [24]. Furthermore, vaccinated hamsters showed robust control of parasitemia in visceral organs, challenged with L. donovani either through needle injection or by natural mode of infected sand fly bite. Importantly, this vector-challenge result validated the efficacy of LmCen-/- as a vaccine candidate during pre-clinical testing and provide stringent evaluation of their performance under natural conditions with respect to needle-initiated infection [25]. This protection was associated with significant higher expression of protective humoral as well as cell mediated immune response, similar to cured VL patients for controlling infection [26]. Moreover, induction of distinct upstream regulators compared to wild type infection predicted by IPA analysis, suggests LmCen-/- as a potent immune-modulatory agents and biomarkers of immunogenicity in human clinical trials.

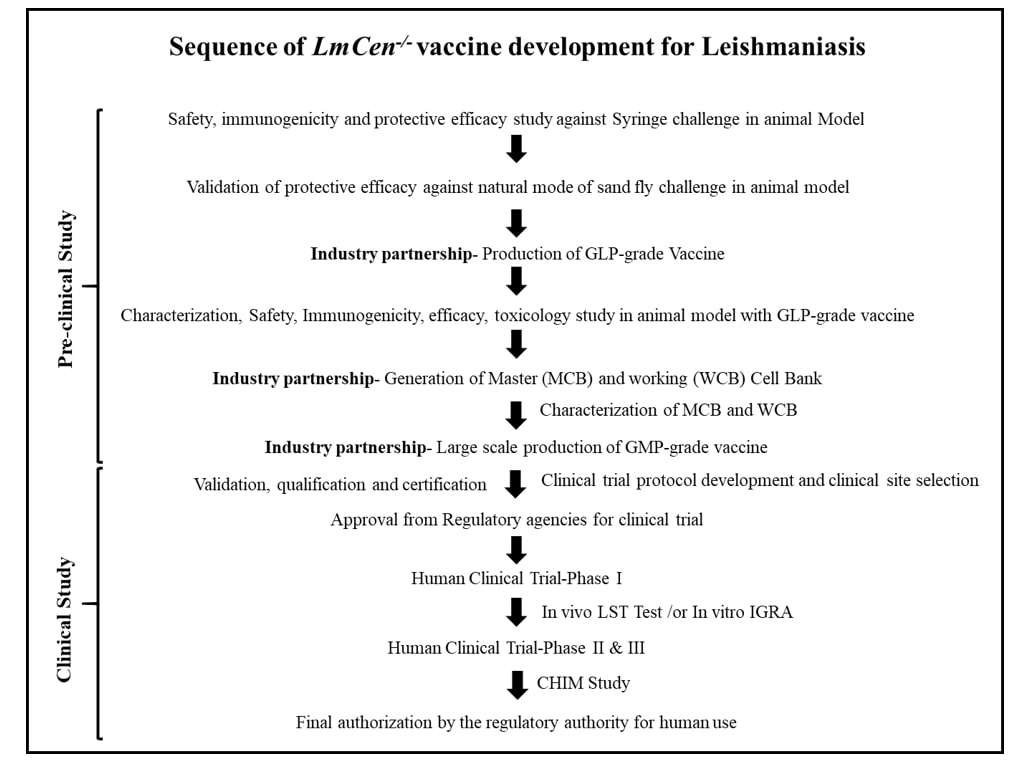

Beyond pre-clinical studies, to evaluate the vaccine potential of a live attenuated vaccine for human clinical trial, several prerequisite need to be satisfied for approval by the regulatory agencies. This include the vaccine strain should be manufactured under current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP). Towards achieving this goal, researchers manufactured LmCen-/- parasites under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) conditions, in a cGMP compliant facility in collaboration with their industry partner, Gennova Biopharmaceuticals Ltd., India. GLP-grade LmCen-/- parasites produced in large scale are also safe, induced significant host protection and prevents mortality against natural mode of sand fly challenge. Importantly, their long-lasting protective efficacy further satisfied the essential characteristics of an efficacious vaccine. In addition, an IFN-γ dominated immune response in PBMCs of healthy human volunteers living in non-endemic regions (United States of America, USA) suggested that LmCen-/- is ready to be tested in human’s clinical trial, corroborated by Osman et al. study [27]. However, the immunological response from non-endemic region human PBMCs needs to be further validated by the GMP-grade parasites in future studies.

Another major challenge associated with Leishmania vaccine development, is the clinical evaluation of the safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of a vaccine. The most traditional way to determine the efficacy of a vaccine is the development of disease [https://www.who.int/biologicals/expert_committee/Clinical_changes_IK_final.pdf], which needs large number of participants and may take long duration to complete the study due to variation of incidence of cases in the endemic areas [28]. Therefore, alternative approaches should be applied which can be invaluable in expediting time to check the safety and efficacy of a vaccines. One approach is the use of sand fly-initiated controlled human infection model (CHIM) to determine the vaccine efficacy against CL during phase II trial [29], previously studied in many other diseases [30-33]. However, the use of such CHIMs model to determine vaccine efficacy against VL remains to be solved. As per epidemiological evidence, exposure to wild-type L. major parasites confer cross-protection against VL in various animal models including humans [20-22,34], suggested that an effective vaccine against CL in CHIM study would provide immunity against VL. Another in vivo approach to define the immune correlates of protection is the re-introduction of Leishmanin Skin Test (LST) as a surrogate biomarker of immunogenicity during phase I study. LST has been used for decades to determine long-lasting protective immunity for both CL and VL [35-38]. Currently GMP-grade leishmanin antigen is not available for clinical purpose anywhere in the world, forcing the practice of LST has to decline. Moreover, advancing the development of leishmanin antigen under GMP condition, strongly suggest re-introduction of LST for the surveillance programs as well as vaccine trials to eliminate the disease. However, the sensitivity of LST is known to vary depending upon the appropriate dose, geographic regions or phase of visceral infection [22,38], suggesting the development of better markers for the assessment of infection and cellular immune response in endemic regions of VL. These findings indicate that an in vitro approach of IFN-γ release assay (IGRA), could be useful to detect Leishmania infection and to assess the immune response of a vaccine candidate during human studies in highly endemic regions of VL [39,40].

In addition, other challenges need to be overcome to develop a vaccine for human trial which includes: development of assays to determine batch to batch consistency, storage condition, evaluation of potential toxicities due to interactions of the components present in the final formulation, complete genome sequence of the GMP-grade parasite to check any off target deletion/mutation, absence of any adventitious agents like Leishmania RNA virus that can exacerbate the disease progression [41], well defined media formulation that is either animal component (serum) free or free from serum containing Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE) [4].

Conclusion

Leishmaniasis is a serious threat globally and the development of a vaccine is a major public health priority. Current understanding of Leishmania pathogenesis and host protective immunity suggested that a single vaccine has the potential to protect against one or more than one species and prevent the disease. Despite substantial efforts by many laboratories, no vaccine is available for human use still to date. The major impediments in Leishmania vaccine research is mostly related to their biosafety, efficacy against natural exposure to infected sand fly bites that can correlates the vaccine success in real field and finally their production. The most advances of new CRISPR gene editing technology, together with surrogate practice (leishmanization) results in new avenues for Leishmania vaccine research that evolved the generation of live attenuated LmCen-/- vaccine with precise deletion of the desired gene. Pre-clinical studies showed that the vaccine has overcome all biosafety issues and single intradermal injection can significantly induce long-lasting host protective immunity to prevent the disease. Importantly, robust and durable protective efficacy of LmCen-/- against both homologous and heterologous challenge through natural sand fly mode, suggests the feasibility of LmCen-/- as a pan-Leishmania vaccine for the first time. Currently, researchers are planning for toxicology study with GLP-grade LmCen-/- vaccine in India. Moreover, they have developed and characterized the Master Cell Bank (MCB) as well as Working Cell Bank (WCB) for the manufacturing of GMP-grade LmCen-/- parasites. Since the site of clinical trial is of critically important, researchers are now planning for Phase 1 study in the non-endemic regions (United states) as well as in the endemic Regions (India, Ethiopia, Sudan, Brazil, Iran etc.) of VL to assess the safety and immunogenicity of this vaccine. They are also in a process of exploring the efficacy of LmCen-/- vaccine in CHIM model.

Conflicts of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

2. Ready PD. Epidemiology of visceral leishmaniasis. Clinical Epidemiology. 2014;6:147–54.

3. Roatt BM, Aguiar-Soares RD, Coura-Vital W, Ker HG, Moreira ND, Vitoriano-Souza J, at al. Immunotherapy and immunochemotherapy in visceral leishmaniasis: promising treatments for this neglected disease. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014 Jun 13;5:272.

4. Volpedo G, Huston RH, Holcomb EA, Pacheco-Fernandez T, Gannavaram S, Bhattacharya P, et al. From infection to vaccination: reviewing the global burden, history of vaccine development, and recurring challenges in global leishmaniasis protection. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2021 Nov 2;20(11):1431-46.

5. van Griensven J, Diro E. Visceral leishmaniasis: recent advances in diagnostics and treatment regimens. Infectious Disease Clinics. 2019 Mar 1;33(1):79-99.

6. Aronson NE, Joya CA. Cutaneous leishmaniasis: updates in diagnosis and management. Infectious Disease Clinics. 2019 Mar 1;33(1):101-17.

7. Rosenthal E, Marty P. Recent understanding in the treatment of visceral leishmaniasis. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2003 Jan 1;49(1):61.

8. Ostyn B, Gidwani K, Khanal B, Picado A, Chappuis F, Singh SP, at al. Incidence of symptomatic and asymptomatic Leishmania donovani infections in high-endemic foci in India and Nepal: a prospective study. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2011 Oct 4;5(10):e1284.

9. Saljoughian N, Taheri T, Rafati S. Live vaccination tactics: possible approaches for controlling visceral leishmaniasis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2014 Mar 31;5:134.

10. Jeronimo SM, Teixeira MJ, Sousa AD, Thielking P, Pearson RD, Evans TG. Natural history of Leishmania (Leishmania) chagasi infection in Northeastern Brazil: long-term follow-up. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2000 Mar 1;30(3):608-9.

11. Bacon KM, Hotez PJ, Kruchten SD, Kamhawi S, Bottazzi ME, Valenzuela JG, et al. The potential economic value of a cutaneous leishmaniasis vaccine in seven endemic countries in the Americas. Vaccine. 2013 Jan 7;31(3):480-6.

12. Lee BY, Bacon KM, Shah M, Kitchen SB, Connor DL, Slayton RB. The economic value of a visceral leishmaniasis vaccine in Bihar state, India. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012 Mar 1;86(3):417.

13. Selvapandiyan A, Dey R, Nylen S, Duncan R, Sacks D, Nakhasi HL. Intracellular replication-deficient Leishmania donovani induces long lasting protective immunity against visceral leishmaniasis. The Journal of Immunology. 2009 Aug 1;183(3):1813-20.

14. Fiuza JA, da Costa Santiago H, Selvapandiyan A, Gannavaram S, Ricci ND, Bueno LL, et al. Induction of immunogenicity by live attenuated Leishmania donovani centrin deleted parasites in dogs. Vaccine. 2013 Apr 3;31(14):1785-92.

15. Dey R, Natarajan G, Bhattacharya P, Cummings H, Dagur PK, Terrazas C, at al. Characterization of cross-protection by genetically modified live-attenuated Leishmania donovani parasites against Leishmania mexicana. The Journal of Immunology. 2014 Oct 1;193(7):3513-27.

16. Zhang WW, Karmakar S, Gannavaram S, Dey R, Lypaczewski P, Ismail N, et al. A second generation leishmanization vaccine with a markerless attenuated Leishmania major strain using CRISPR gene editing. Nature Communications. 2020 Jul 10;11(1):1-4.

17. Mohebali M, Nadim A, Khamesipour A. An overview of leishmanization experience: A successful control measure and a tool to evaluate candidate vaccines. Acta Tropica. 2019 Dec 1;200:105173

18. Nadim A, Javadian E, Tahvildar-Bidruni G, Ghorbani M. Effectiveness of leishmanization in the control of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique et de ses Filiales. 1983 Aug 1;76(4):377-83.

19. Karmakar S, Ismail N, Oliveira F, Oristian J, Zhang WW, Kaviraj S, et al. Preclinical validation of a live attenuated dermotropic Leishmania vaccine against vector transmitted fatal visceral leishmaniasis. Communications Biology. 2021 Jul 30;4(1):1-4.

20. Romano A, Doria NA, Mendez J, Sacks DL, Peters NC. Cutaneous infection with Leishmania major mediates heterologous protection against visceral infection with Leishmania infantum. The Journal of Immunology. 2015 Oct 15;195(8):3816-27.

21. Porrozzi R, Teva A, Amaral VF, da Costa MV, GRIMALDI G. Cross-immunity experiments between different species or strains of Leishmania in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta). The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2004 Sep 1;71(3):297-305.

22. Zijlstra EE, El-Hassan AM, Ismael A, Ghalib HW. Endemic kala-azar in eastern Sudan: a longitudinal study on the incidence of clinical and subclinical infection and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1994 Dec 1;51(6):826-36.

23. Romano A, Inbar E, Debrabant A, Charmoy M, Lawyer P, Ribeiro-Gomes F, et al. Cross-species genetic exchange between visceral and cutaneous strains of Leishmania in the sand fly vector. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 Nov 25;111(47):16808-13.

24. Aslan H, Dey R, Meneses C, Castrovinci P, Jeronimo SM, Oliva G, et al. A new model of progressive visceral leishmaniasis in hamsters by natural transmission via bites of vector sand flies. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2013 Apr 15;207(8):1328-38.

25. Peters NC, Kimblin N, Secundino N, Kamhawi S, Lawyer P, Sacks DL. Vector transmission of leishmania abrogates vaccine-induced protective immunity. PLoS pathogens. 2009 Jun 19;5(6):e1000484.

26. Kemp K, Kemp M, Kharazmi A, Ismail A, Kurtzhals JA, Hviid L, et al. Leishmania-specific T cells expressing interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and IL-10 upon activation are expanded in individuals cured of visceral leishmaniasis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 1999 Jun;116(3):500-4.

27. Osman M, Mistry A, Keding A, Gabe R, Cook E, Forrester S, at al. A third generation vaccine for human visceral leishmaniasis and post kala azar dermal leishmaniasis: First-in-human trial of ChAd63-KH. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2017 May 12;11(5):e0005527.

28. Rijal S, Sundar S, Mondal D, Das P, Alvar J, Boelaert M. Eliminating visceral leishmaniasis in South Asia: The Road Ahead. BMJ. 2019 Jan 22;364.

29. Ashwin H, Sadlova J, Vojtkova B, Becvar T, Lypaczewski P, Schwartz E, et al . Characterization of a new Leishmania major strain for use in a controlled human infection model. Nature Communications. 2021 Jan 11;12(1):1-2.

30. Payne RO, Griffin PM, McCarthy JS, Draper SJ. Plasmodium vivax controlled human malaria infection–Progress and Prospects. Trends in Parasitology. 2017 Feb 1;33(2):141-50.

31. Kirkpatrick BD, Whitehead SS, Pierce KK, Tibery CM, Grier PL, Hynes NA, et al. The live attenuated dengue vaccine TV003 elicits complete protection against dengue in a human challenge model. Science Translational Medicine. 2016 Mar 16;8(330):330ra36.

32. Cooper MM, Loiseau C, McCarthy JS, Doolan DL. Human challenge models: tools to accelerate the development of malaria vaccines. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2019 Mar 4;18(3):241-51.

33. Ferreira DM, Neill DR, Bangert M, Gritzfeld JF, Green N, Wright AK, et al. Controlled human infection and rechallenge with Streptococcus pneumoniae reveals the protective efficacy of carriage in healthy adults. American Journal of Respiratory And critical Care Medicine. 2013 Apr 15;187(8):855-64.

34. Khalil EA, Zijlstra EE, Kager PA, El Hassan AM. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of Leishmania donovani infection in two villages in an endemic area in eastern Sudan. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 2002 Jan;7(1):35-44.

35. Krolewiecki AJ, Almazan MC, Quipildor M, Juarez M, Gil JF, Espinosa M, at al. Reappraisal of Leishmanin Skin Test (LST) in the management of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis: A retrospective analysis from a reference center in Argentina. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2017 Oct 5;11(10):e0005980.

36. Pinheiro ABS, Kurizky PS, Ferreira MF, Mota MAS, Ribeiro JS, Oliveira Filho EZ, et al. The accuracy of the Montenegro skin test for leishmaniasis in PCR-negative patients. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2020;53:e20190433.

37. Pampiglione S, Manson-Bahr PE, La Placa M, Borgatti MA, Musumeci S. Studies in Mediterranean leishmaniasis: 3. The leishmanin skin test in kala-azar. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1975 Jan 1;69(1):60-8.

38. Gidwani K, Rai M, Chakravarty J, Boelaert M, Sundar S. Evaluation of leishmanin skin test in Indian visceral leishmaniasis. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine.

39. Gidwani K, Jones S, Kumar R, Boelaert M, Sundar S. Interferon-gamma releas) as a potential marker of infection for Leishmania donovani, a proof of concept study. PLoS neglAoun K, Bouratbine A. Use of an Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) to test T-cell responsiveness to soluble Leishmania infantum antigen in whole blood of dogs from endemic areas. Veterinary parasitology. 2017 Nov 15;246:88-92.

40. Zribi L, El-Goulli AF, Ben-Abid M, Gharbi M, Ben-Sghaier I, Boufaden I, et al. Use of an Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) to test T-cell responsiveness to soluble Leishmania infantum antigen in whole blood of dogs from endemic areas. Veterinary Parasitology. 2017;246:88-92.

41. Ives A, Ronet C, Prevel F, Ruzzante G, Fuertes-Marraco S, Schutz F, et al. Leishmania RNA virus controls the severity of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Science. 2011 Feb 11;331(6018):775-8.