Keywords

Hand, Foot and mouth disease, Bifidobacterium, Escherichia coli, 16S rRNA, Alpha diversity analysis,

Commentary

We read with interest the article by Yin et al analyzing the changing characteristic of gut microbiota of hand, foot, and mouth disease (HFMD) [1]. In the last ten years, gut microbiota has attracted a great deal of academic interest which was linked to the occurrence, the development and progression of various diseases, including enterovirus infection [2-5]. HFMD, a typical gastrointestinal contagious disease, is one of the top three class C notifiable infectious diseases in China, which has been confirmed to have altered intestinal flora structure [6]. Besides, studies have reported that probiotic-assisted treatment of HFMD is effective [7]. The intestinal flora is always in dynamic balance under normal conditions, and plays an irreplaceable role in the formation, repair, and functional stabilization of the intestinal mucosal barrier in a variety of ways. Yet, when dysbiosis occurs, it can directly affect the structure and function of the intestinal barrier, thereby triggering a pro-inflammatory state in the host, altering intestinal permeability [8]. It has also been shown that enteroviruses can target gastrointestinal (GI) epithelial cells and utilize intestinal bacteria to enhance multiplication, pathogenesis, and transmission, resulting in the development of the disease [9,10]. Therefore, a rising number of studies have been devoted to exploring the role of the gut microbiota in the development of HFMD progression. Previous studies on the intestinal flora of HFMD initially employed the fluorescence quantitative polymerase chain reaction technology (PCR) to detect the content of Bifidobacterium and Escherichia coli in feces [1,11-12]. The results of all these studies showed altered distribution of intestinal flora in children with HFMD. The ratio of Bifidobacterium/Escherichia coli in the intestines of the case group was significantly lower than that of the control group. Among them, Su et al. found that the value of B/E in severe HFMD was lower than that of control children (1.23 ± 0.46) in both the early stage (0.96 ± 0.24) and the convalescent stage (1.02 ± 0.31) of the disease [12]. Advances in gut flora sequencing technology, from PCR, 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA), microgenomes to microtranscriptome, have greatly improved the accuracy of gut flora detection. Based on these new sequencing methods, the study can still obtain the same results, that the distribution of the gut flora of children with HFMD differs significantly from that of controls [13-17]. Nevertheless, the results of all current HFMD studies are inconsistent, and it is difficult to summarize the changing rules of the gut microbiota of the disease. In addition, most of these studies have been conducted on small sample sizes, so further validation with large samples is needed. Herein, we conducted a case-control study investigated 749 participants (including 262 HFMD patients and 487 healthy children) from Heyuan and Jiangmen regions in Guangdong, China. Epidemiological information and fecal samples were collected with the aim of validating the change characteristic in gut microbiota communities in individuals with HFMD and further revealing the relationship and the underlying mechanisms by 16S rRNA gene amplicon. It is also important to note that shared data related to HFMD enteric flora are not currently available in public databases, so we reorganized and presented a high-quality sequences dataset (713 study participants, including 459 healthy children and 254 patients with HFMD) to the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) platform, under GSA ID CRA009110 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA009110), to share them with the public. We hope that these resources can be fully utilized and validated in comparison with other HFMD data, which will be conducive to exploring the potential relationship between the gut microbiota and HFMD, and provide a reference for intervention and treatment strategies for this disease.

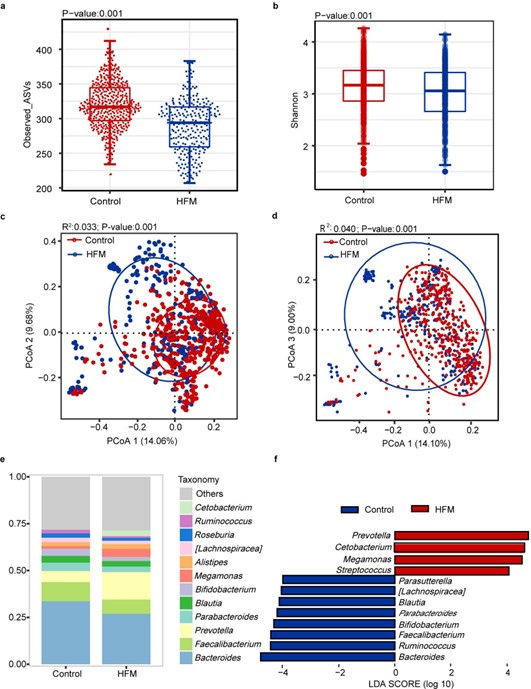

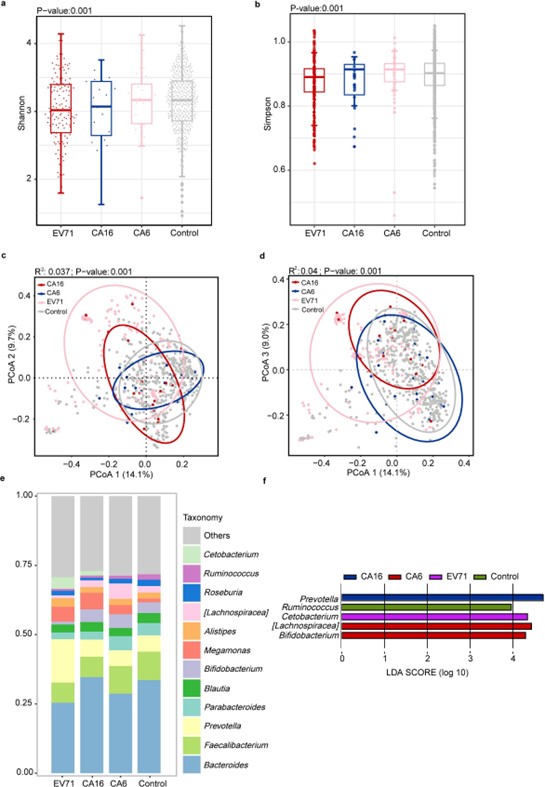

By analyzing 713 participants, we observed the same results as in other studies, a significant change in the microbiota profile of children with HFMD compared with that of healthy children. Alpha diversity analysis of the two groups based on the Simpson and Shannon indices revealed that the HFMD group had lower richness and evenness (Figures 1a and 1b). Beta diversity analysis of the two groups based on the bray?curtis distance and unifrac distances indicated that the composition of the gut microbiota of the HFMD group was significantly different from that of the control group (Figures 1b and 1c). The stack plot showing the bacterial structure of the two groups, with Bacteroidetes, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Parabacteroides, Blautia, and Bifidobacterium being the major genera in both groups (Figure 1e). The linear discriminant analysis effect size (Lefse) analysis was used to further identify the bacteria that differed between the HFMD and control groups, confirming that Prevotella, Cetobacterium, Megamonas and Streptococcus were enriched in children with HFMD, and Bacteriodes, Ruminococcus, Faecalibacterium and Bifidobacterium were depleted (Figure 1f). There is less information on studies analyzing and comparing the intestinal flora in patients infected with different enteroviruses, while the type of enterovirus is one of the most essential considerations in analysis of the gut microbiota of HFMD. We found that the intestines infected with three enteroviruses, including enterovirus A71 (EV71), coxsackievirus A16 (CA16) and coxsackievirus A6 (CA6), displayed significant gut microbiome diversity and compositional shift. The alpha diversity index of all three enterovirus types was lower than that of the control group, with EV71 group lower than CA16 and CA6 (Figures 2a and 2b). Distinctly, Zhu et al. reported that diversity and abundance of gut microbiota were not significantly altered in children infected with EV71 [17]. PCoA analysis showed the overlap area between EV71, and controls was the smallest comparing with other enteroviruses and CA6 was the largest, implying that patients with EV71 positive had the highest degree dysbiotic gut microbiota (Figures 2c and 2d). Additionally, Bacteroidetes, Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Parabacteroides, Blautia and Bifidobacterium were enriched in four groups (Figure 2e). Prevotella, Cetobacterium, and Bifidobacterium were enriched in CA16, EV71 and CA6 groups, respectively, whereas Ruminococcus was reduced in the enteroviruses-positive groups (Figure 2f). Conversely, Shen et al’s study pointed that 10 bacterial species were unidirectionally enriched in the EV71 group, including Bacteroides, Blautia, Ruminococcus, Clostridium, Faecalibacterium, Alistipes and Pseudofavonifractor compared to other CV-A-positive groups [14].

Figure 1. Comparison of the gut microbiota profile between HFMD and control groups. (a,b) Alpha diversity. Comparison of the diversity of high-abundant bacteria (the Shannon and Simpson indices) in the two groups (P<0.05, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests). (c,d) Beta diversity. Principal coordinate analysis based on bray-curtis distance and unifrac distance showing patterns of separation in the bacterial communities between the two groups. PCoA1, PCoA2, and PCoA3 represent the top three principal coordinates, and the explanation of diversity is expressed as a percentage. Each point represents a single sample and is colored based on the group. (e) Average relative abundance of the predominant bacterial taxa in each group at the genus level. (f) Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis. Differential bacterial taxonomy abundance between the groups (LDA>2).

Figure 2. Comparison of the gut microbiota profile between EV71, CA16, CA6 and control groups. (a,b) Alpha diversity. Comparison the diversity of high-abundant bacteria (the shannon and simpson indices) among EV71, CA16, CA6, and control groups (P<0.05, Kruskal-Wallis tests). (c-d) Beta diversity. Principal coordinate analysis based on bray?curtis distance and unifrac distance showing patterns of separation in the bacterial communities between the two groups. PCoA1, PCoA2 and PCoA3 represent the top three principal coordinates, and the explanation of diversity is expressed as a percentage. Each point represents a single sample and is coloured based on the group. (e) Average relative abundance of the predominant bacterial taxa at the genus level among EV71, CA16, CA6 and control groups. (f) Linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis. Differential bacterial taxonomy abundance among EV71, CA16, CA6 and control groups (LDA>2).

Our findings and other study observations indicated that the gut microbiota of patients with HFMD exhibits dysbiosis. Interestingly, infection with different types of enteroviruses leads to different characteristics of intestinal changes. There are several inconsistencies in the findings that need to be further confirmed by additional studies. Taken together, gut microbiota are essential breakthroughs in the prevention and interventional treatment of HFMD, and it is hoped that sharing the database will bring more attention to the field of gut research in HFMD.

Author Contributions

WW made contributions to the study design. WW and MJX supervised computational work. LZF processed the samples. GXY performed the informatics analyses, interpreted the results, and designed figures. GXY, YM, HDY, and HYT searched literature and drafted the first version of the manuscript. WW and MJX corrected and thoroughly edited the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Code Availability

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories (CRA009110, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA009110).

Funding

This work was funded by the Science and Technology Planning Project Foundation of Guangzhou city (202102080584).

Competing Interests

None declared.

References

2. Winglee K, Eloe-Fadrosh E, Gupta SS, Guo HD, Fraser C, Bishai W. Aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection causes rapid loss of diversity in gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97048.

3. Heidrich B, Vital M, Plumeier I, Döscher N, Kahl S, Kirschner J, et al. Intestinal microbiota in patients with chronic hepatitis C with and without cirrhosis compared with healthy controls. Liver Int. 2018;38(1):50-58.

4. Schuijt TJ, Lankelma JM, Scicluna BP, de Sousa e Melo F, Roelofs JJ, et al. The gut microbiota plays a protective role in the host defence against pneumococcal pneumonia. Gut. 2016;65(4):575-83.

5. Sun Y, Ma YF, Lin P, Tang YW, Yang LY, Shen YZ, et al. Fecal bacterial microbiome diversity in chronic HIV-infected patients in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5(4):e31.

6. Mao Y, Zhang N, Zhu B, Liu JL, He RX. A descriptive analysis of the Spatio-temporal distribution of intestinal infectious diseases in China. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):766.

7. Zhang Q, Mei ZJ, Wang Y. Efficiency of probiotics for treatment of hand foot and mouth disease in Chinese children: a meta analysis. Chinese Journal of Microecology. 2021;33(08):905-910+923.

8. Baumgart DC, Dignass AU. Intestinal barrier function. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2002;5(6):685-94.

9. Robinson CM. Enteric viruses exploit the microbiota to promote infection. Curr Opin Virol. 2019;37:58-62.

10. Kuss SK, Best GT, Etheredge CA, Pruijssers AJ, Frierson JM, Hooper LV, et al. Intestinal microbiota promote enteric virus replication and systemic pathogenesis. Science. 2011;334(6053):249-52.

11. Quan YL. Enteric flora distribution of hand- foot -and mouth disease infants, and its influence on patients' immunofunction and enteric mucosal permeability. Chinese Journal of Coloproctology. 2020;40(04):26-28.

12. Su YF, Chen J, Wang L, Wen J. Correction between intestinal intestinal flora mucosal permeability in patient children with severe hand-foot-mouth disease. Chinese Journal of Woman and Child Health Research. 2016;27(03):323-325.

13. Li WR, Zhu Y, Li YY, Shu M, Wen Y, Gao XL, et al. The gut microbiota of hand, foot and mouth disease patients demonstrates down-regulated butyrate-producing bacteria and up-regulated inflammation-inducing bacteria. Acta Paediatr. 2019;108(6):1133-1139.

14. Shen CG, Xu Y, Ji JK, Wei JL, Jiang YJ, Yang Y, et al. Intestinal microbiota has important effect on severity of hand foot and mouth disease in children. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):1062.

15. Guo XY, Lan ZX, Wen YL, Zheng CJ, Rong ZH, Liu T, et al. Synbiotics Supplements Lower the Risk of Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease in Children, Potentially by Providing Resistance to Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;30(11):729-756.

16. Liu H. Characteristics of intestinal flora in children with hand-foot-mouth disease. Suzhou university. 2020.

17. Zhu SY, Shen N, Zhou Y, Chen M, Qiao JB, Jiang YZ. Analysis of the structural characteristics of intestinal flora in EV71 hand-foot-mouth disease [J]. Journal of Xuzhou Medical University. 2022;42(05): 353-7