Keywords

T regulatory cells, Cellular therapy, Clinical application, Foxp3, Helios

Abbreviations

ADSCC: Abu Dhabi Stem Cells Center; ECP: Extracorporeal photopheresis; eTreg: Effector Treg; Foxp3: Forkhead box P3; GMP: Good Manufacturing Practices; GvHD: Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease; iTreg: Induced in vitro Treg; mDC: Myeloid dendritic cell; nTreg: Naïve Treg; pDC: Plasmacytoid dendritic cell; pTreg: Peripherally induced Treg; TCR: T-cell receptor; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor-β; Treg: Regulatory T cell; tTreg: Thymic-derived Treg cell

Editorial

Since Gershon and Kondo’s initial description of suppressor T cells as antigen-specific T cells that regulate immune responses [1], several advances have taken place on the biology and potential applications of regulatory T cells (Tregs) in clinical settings. After that, Sakaguchi et al. identified Treg cells capable of protecting lymphopenic mice against autoimmune disease produced by neonatal thymectomy [2], and Morrissey et al. characterized them as CD4+ T cells expressing high levels of CD25 or low CD45RB levels [3]. However, the lack of specificity of these markers, which are shared with activated T cells and the conditions of the experimental settings, raised doubts about their role in immunological tolerance. The discovery of the transcription factor Foxp3 was the turning point in acknowledging Treg cells as a specific lineage [4].

Nowadays, it is well accepted that Tregs display a critical role in the immune homeostasis (“immunostains”) status, providing restraint to different immune system’s adaptations. CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells can suppress immune activation and, therefore, are critical subsets maintaining self-tolerance and in the prevention of allograft rejection, allergy, fetal rejection, and an exaggerated immune response towards commensal pathogens [5,6].

Several Treg subpopulations have been defined in vivo; thymic-derived Treg cells (tTreg) and peripherally (extrathymically) induced Tregs (pTregs) derived from conventional CD4+Foxp3− T cells. In addition, another subset can be generated in vitro (iTregs) in the presence of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and IL-2 cell cultures [7].

Still, the pool of CD4+Foxp3+ Treg cells is heterogeneous in animals and humans. They were initially characterized phenotypically as a CD4+CD25highCD127low T cell population, from which 22 subsets can be identified by mass cytometry analyses [6]. Three phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets can be developmentally defined in human CD4+Foxp3+ cells: 1) CD45RA+Foxp3low naïve or resting Treg (nTreg) derived from the thymus, 2) CD45RA-Foxp3high effector or activated Treg (eTreg), and 3) non-suppressive CD4+ T cells with low expression of Foxp3 [6].

Along with the Foxp3 expression, which plays crucial roles in the differentiation and function of Tregs [7], another transcription factor, Helios, describes a stable phenotype of Treg cells and is also closely associated with the demethylation of a Treg-specific demethylated region of the Foxp3 locus [8]. Additionally, there is evidence that Helios expression stabilizes the function and phenotype of Foxp3+ Tregs in certain inflammatory environments, and this specific phenotype represents more potent suppressor cells in both humans and animal models [8]. Conversely, Helios+ and Helios- Treg subpopulations are phenotypically and functionally distinct and express different T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoires. For instance, a higher percentage of Helios+ Treg expressed CD103, Nrp-1, OX40, TNFRII, and CD69 compared to Helios− Tregs [9].

Hence, promising CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs-based therapies, through the manipulation of antigen-specific cells, have been studied, and several clinical trials are ongoing. Most of these studies apply ex vivo expanded Tregs (due to the low count in human peripheral blood), but others are based on depleting these cells, depending on the target effects. For instance, there are many trials based on donor or autologous Tregs infusion (expression of CD4+Foxp3+Helios+ phenotype not specified) in patients with, as examples, Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease (GvHD), systemic lupus erythematosus, ulcerative colitis, but also with its depletion (e.g., Treg cells depletion for amplifying graft-versus-tumor effect before donor lymphocytes infusion).

Although the identification of the CD4+ Treg subsets is well established, the CD8+ Treg subset is more recent, and the molecular mechanisms controlling their function remain to be discovered. CD8+ Treg lymphocytes have an inhibitory effect through cell contact. In murine and human models, it has been described that CD8+ Tregs can show negative signaling through CTLA-4 or PD-1 or the release of immunosuppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β [10].

Since exclusive markers for this population of regulatory lymphocytes have not yet been described, the identification of this population should be studied across the expression of regulatory markers, the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines, and inhibition of proliferation effector T lymphocytes.

CD8+ Treg cells appear to be a heterogeneous population, while the role of Foxp3 in CD8+ Treg lymphocytes is not elucidated, although Foxp3-expressing CD8+ Tregs are immunosuppressive during GvHD and skin transplantation [11].

In general, although Treg therapy in humans remains challenging in terms of manufacturing processes (e.g., isolation, ex vivo expansion, cryopreservation protocols), cells dose, and product stability, among others, some publications have reported the safety and efficacy of utilizing CD4+ Tregs as therapy in GvHD, solid organ transplantation, and autoimmune disorders [12].

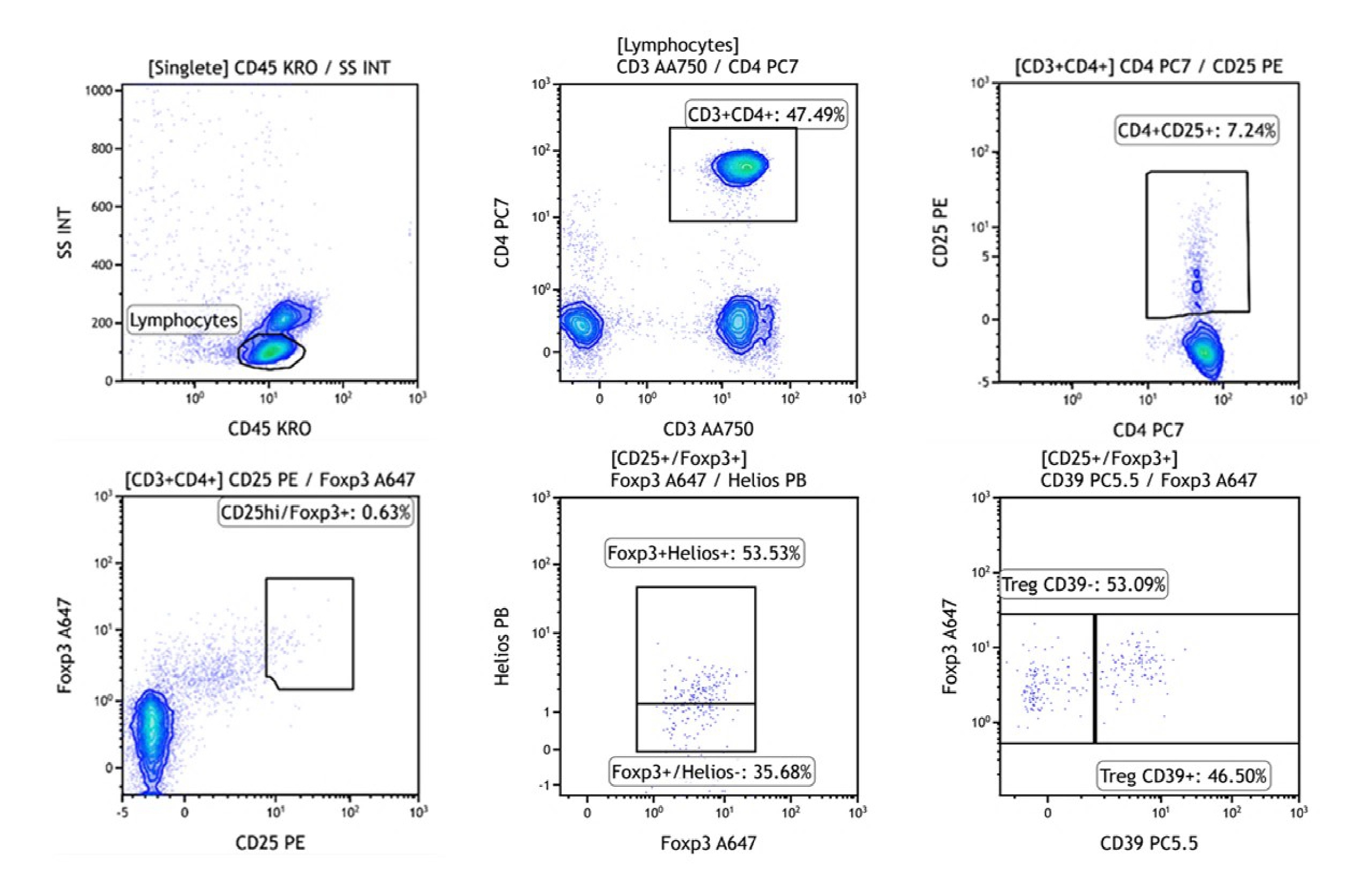

In our facility, the Abu Dhabi Stem Cells Center (ADSCC), we have found that the absolute count of CD4+CD25highFoxp3+Helios+ Treg subsets (phenotypical characterization shown in Figure 1) increased in GvHD patients undergoing extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP) therapy after six or seven procedures, along with other potential immunoregulatory effects, such as a continuous decrease in CD8+ T cells and effector subpopulations, and myeloid dendritic cells (mDC):plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC) ratios (data not yet published). In addition, we are planning to certify the Cells Processing Laboratory as per Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) requirements and combining with the rest of the provisions in place, like apheresis services, capabilities for cell sorting, and cells expansion, our Group shall shortly conduct further preclinical and clinical studies using CD4+CD25highFoxp3+Helios+ Treg cells.

Figure 1: Strategy to quantify human CD4+CD25highFoxp3+Helios+ Tregs in whole blood using DuraClone IM Treg, Beckman Coulter B53346 (data were collected on Navios EX flow cytometer).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This Editorial did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge ADSCC Management and Cells Processing Laboratory staff for supporting part of the findings reported in this manuscript.

References

2. Sakaguchi S, Takahashi T, Nishizuka Y. Study on cellular events in post-thymectomy autoimmune oophoritis in mice. II. Requirement of Lyt-1 cells in normal female mice for the prevention of oophoritis. J Exp Med. 1982;156(6):1577-1586.

3. Morrissey PJ, Charrier K, Braddy S, Liggitt D, Watson JD. CD4+ T cells that express high levels of CD45RB induce wasting disease when transferred into congenic severe combined immunodeficient mice. Disease development is prevented by cotransfer of purified CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178(1):237-244.

4. Brunkow ME, Jeffery EW, Hjerrild KA, Paeper B, Clark LB, Yasayko SA, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27(1):68-73.

5. Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells and Foxp3. Immunol Rev. 2011;241(1):260-8.

6. Mohr A, Malhotra R, Mayer G, Gorochov G, Miyara M. Human FOXP3+ T regulatory cell heterogeneity. Clin Transl Immunology. 2018;7(1):e1005.

7. Kanamori M, Nakatsukasa H, Okada M, Lu Q, Yoshimura A. Induced Regulatory T Cells: Their Development, Stability, and Applications. Trends Immunol. 2016;37(11):803-11.

8. Yu WQ, Ji NF, Gu CJ, Wang YL, Huang M, Zhang MS. Coexpression of Helios in Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells and Its Role in Human DiseaThis Dis Markers. 2021;2021:5574472.

9. Thornton AM, Lu J, Korty PE, Kim YC, Martens C, Sun PD, et al. Helios+ and Helios- Treg subpopulations are phenotypically and functionally distinct and express dissimilar TCR repertoires. Eur J Immunol. 2019;49(3):398-412.

10. Vieyra-Lobato MR, Vela-Ojeda J, Montiel-Cervantes L, López-Santiago R, Moreno-Lafont MC. Description of CD8+ regulatory T lymphocytes and their specific intervention in graft-versus-host and infectious diseases, autoimmunity, and cancer. J Immunol Res. 2018; 5:3758713.

11. Churlaud G, Pitoiset F, Jebbawi F, Lorezon R, Belier B, Rosenzwajg M, et al. Human and mouse CD8+ CD25+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells at steady state and during interleukin-2 therapy. Front Immunol. 2015; 6:171.

12. Golab K, Leveson-Gower D, Wang XJ, Grzanka J, Marek-Trzonkowska N, Krzystyniak A, et al. Challenges in cryopreservation of regulatory T cells (Tregs) for clinical therapeutic applications. Int Immunopharmacol. 2013;16(3):371-5.