Abstract

The identification of new mutations in SARS-CoV-2 and their roles in the viral fitness towards evolution and survival to face the selective pressure imposed by the human host immune response have become the target of great attention recently. As result, concerns related to the emergence of novel variants with more transmissibility and pathogenic potential have led many countries to apply more restrictive measures to avoid increase in the number of infections and collapse of healthcare systems. Re-infection of apparently recovered individuals and cases of co-infection with different variants have also been the focus of studies aiming to investigate whether the vaccines currently used may also be protective against the new emerging variants. This commentary is intended to extend the findings underlying the questions related to the impact of new mutations or combination of them to the efficacy of the developed vaccines and possible changes in the clinical features of COVID-19.

Keywords

Genome sequencing, SARS-CoV-2, Vaccine, Immunity, Virus evolution, Mutation

Introduction

Since its emergence in the end of 2019, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus became a challenge for the healthcare systems around the globe and caused a great impact in the socioeconomic activities with dramatic consequences worldwide. As of July 2021, the virus has been responsible for more than 181,715,917 cases of infection and more than 3,933,152 deaths worldwide [1].

When COVID-19 was recognized as pandemic by the World Health Organization on 11th of March 2020 [2], given the increasingly number of cases and death toll worldwide, one of the many questions raised was whether reinfection could occur. Soon, several case reports became available suggesting this possibility [3-6]. At first, the literature reports did not present sufficient strong data supporting this evidence, but later, re-infection was confirmed by genomic sequencing of different virus variants, isolated at different times during first and second episodes of COVID-19 in the same individual [7-10]. This finding shed light to another important question related to the durability of immunity induced by SARS-CoV-2 natural infections. In addition, it put into perspective at what degree mutations could promote significant changes in the biological behavior of the virus and how these mutations could impact the efficacy of the vaccines under development [11].

Now, it is known that waning immunity may occur in patients who have recovered from COVID-19 infection and this can contribute for a second episode of re-infection [12-14]. Also, some mutations can increase the transmissibility of the virus and consequently increase the number of cases and hospitalizations if prevention measurements are not taken [15]. Notably, these findings suggest that the virus may continue to circulate in human population for a period even if we reach the herd immunity due to natural infection or vaccination [16].

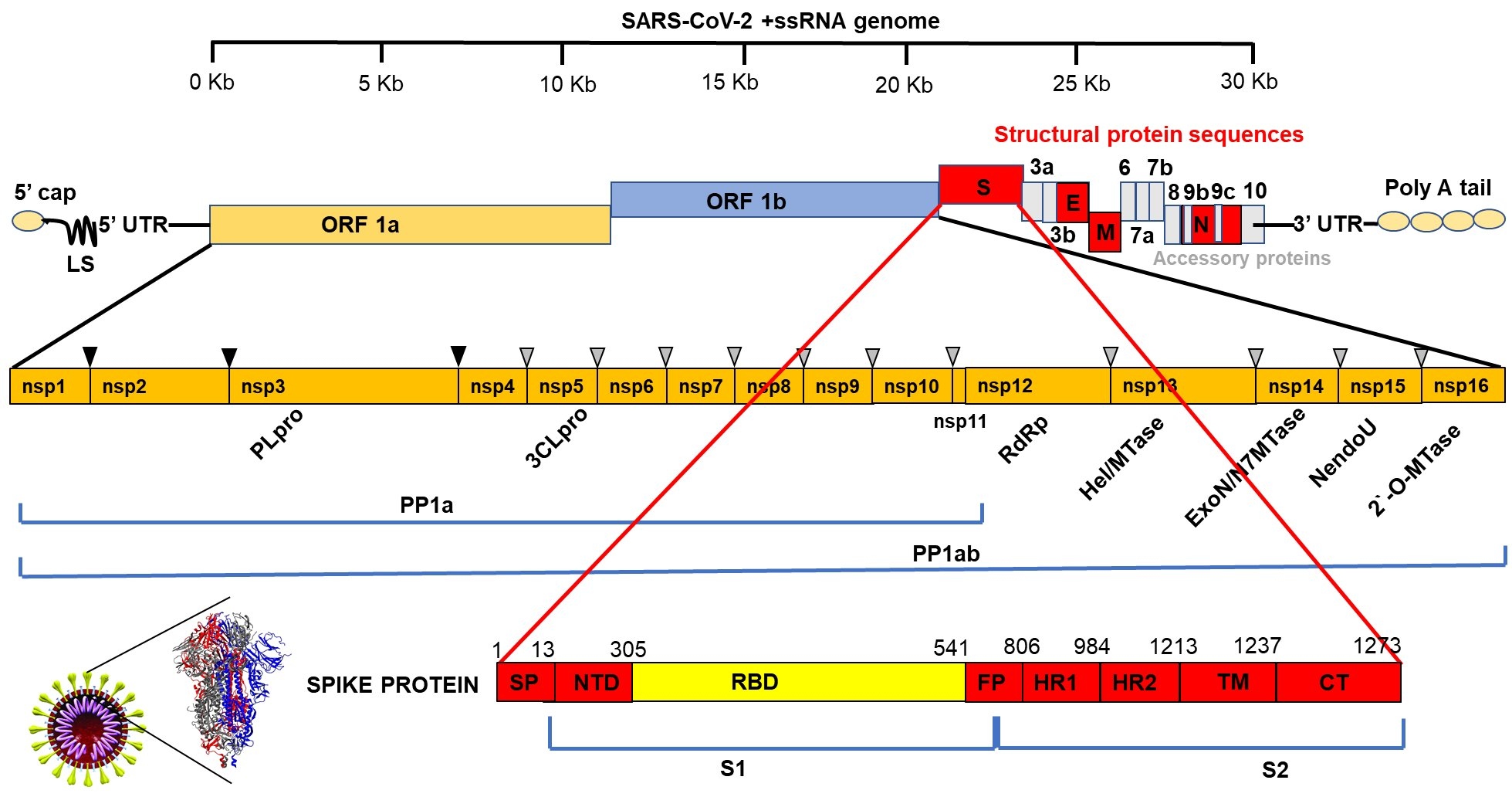

The Genetic Makeup of SARS-CoV-2

The etiologic agent of COVID-19 belongs to the beta subgrouping of the Coronaviridae family and are enveloped viruses containing a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA. The genome is 29.9 kb in size and comprises 13-15 open reading frames (ORFs) from which 12 are functional encompassing 11 coding genes that generate about 12 expressed proteins [17,18]. Among these proteins are four major structural proteins named spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M) and nucleocapsid (N), which play important role in viral entry, host cell membrane fusion and mature viral structure integrity [19-23]. Spike protein is one of the most studied proteins due to its relevant role in virus infectivity through binding to the human cell receptor known as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE2) [20,21]. This binding occurs specifically at the receptor binding domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and is the most variable region of the coronavirus genomes [22,23]. Due to its pivotal role in SARS-CoV-2 infectivity the spike protein is the main target for the development of vaccines and therapeutic drugs.

Besides structural proteins the virus genome expresses non-structural proteins involved in viral RNA synthesis and processing. Some of these proteins have been shown to promote cellular mRNA degradation, block host cell translation and inhibition of innate immune response [24-26]. Among the non-structural proteins, the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Nsp12-RdRp) and 3’-to-5’ exoribonuclease (Nsp14-ExoN) proteins have received great attention due to their essential role in viral replication and recombination and are also included in the group of possible targets for drug development [27,28] (Figure 1). Therefore, although there are some proteins or genes considered key for the viral infectivity and pathogenicity, whole genomic sequences of different samples of isolated virus must be closely monitored to identify changes caused by mutations that may confer better fitness and survival of the virus in human body.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of SARS-CoV-2 genome showing the Open Reading frames (ORFs) for non-structural (nsps) and structural proteins with emphasis to the 1273 amino acids Spike (S) protein. SP: Signal Peptide; NTD: N Terminus Domain; RBD: Receptor Binding Domain; FP: Fusion Peptide; TM: Transmembrane Domain; CT: Cytoplasm Domain. Spike protein forms a trimeric structure shown on the left given the crown-like appearance surrounding the viral particle typical of coronaviruses.

Genomic Sequencing and Identification of New Variants with Potential Risk

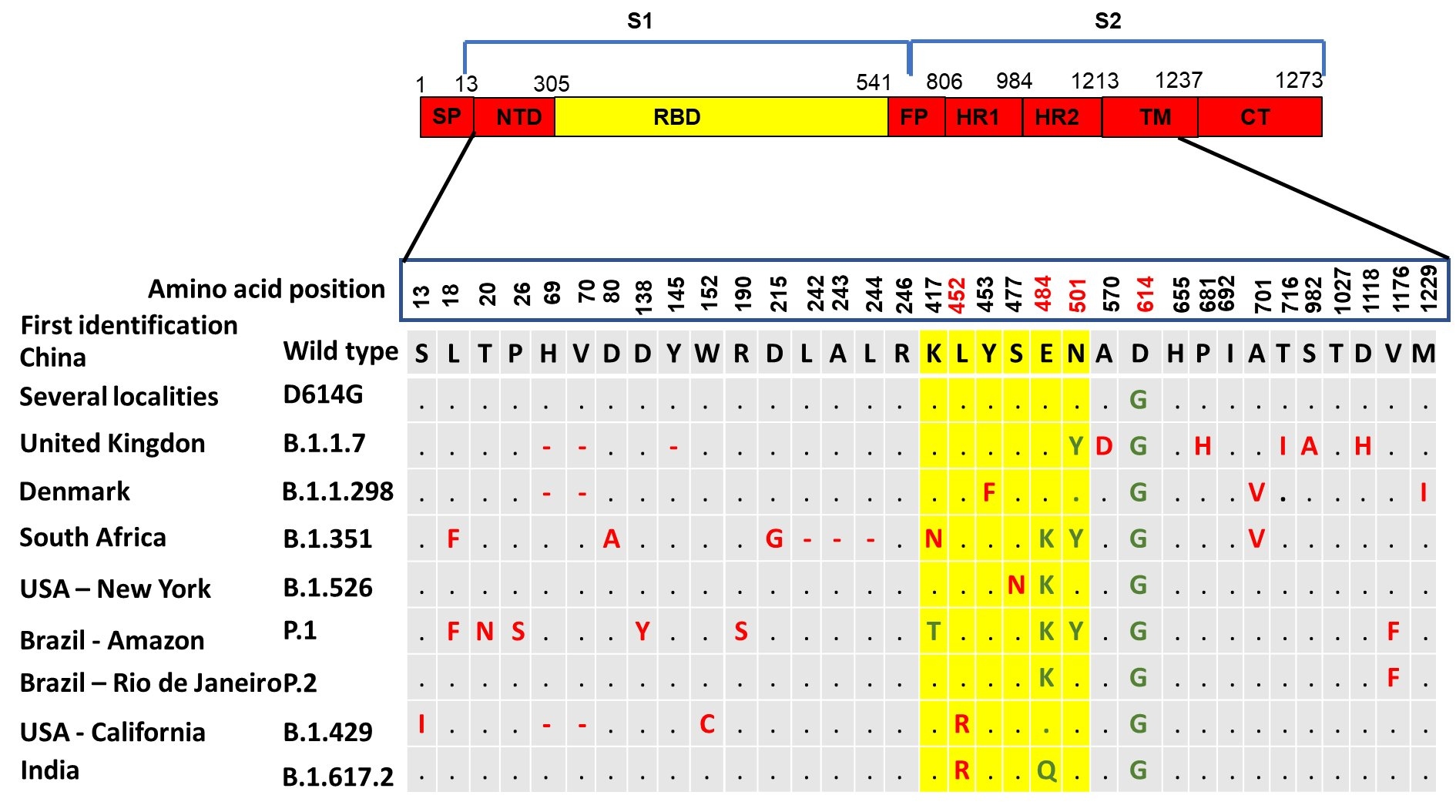

One of the hallmarks in the management of COVID-19 pandemic compared to other pandemics occurred in the past is the use of genomic sequencing approach to follow up virus evolution and spreading across the globe almost in real time. The surveillance of viral genomic variations has been pivotal for the understanding of SARS-CoV-2 epidemiology and alterations in its biological features [29]. By July 7, 2021 there were more than 2,165,530 whole SARS-CoV-2 genomic sequences from different countries uploaded to the online platform The Global Initiative on Sharing Avian Influenza Data (GISAID) database, one of the open access genomic database from all influenza viruses and the coronavirus causing COVID-19 [30-32]. These sequences have helped to understand phylogenetic relationship between the SARS-CoV-2 isolated from different places and group them into clades or lineages. This type of phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes revealed that they are under evolutionary selection in the human host and sometimes with parallel evolution events as indicated by the emergence of same mutation in two different human hosts [33]. With this approach it has been possible for example to track the rise of mutations like D614G (part of the variant identified at the beginning of the pandemic) or the currently most common mutations like N501Y (part of the UK variant) and E484K (part of variants identified in South Africa and Brazil).

Several viral mutations have been identified since the first SARS-CoV-2 genome was sequenced [34,35]. Most of these mutations identified so far is neutral and rarely affected viral fitness. Moreover, most of them did not affect the clinical outcome despite more detailed analysis are still necessary. Even though, the few mutations that have been identified as changing the fitness of SARS-CoV-2 are faced with great concern and their frequencies have been used to determine the level of restriction measures necessary to decrease the dissemination of COVID-19.

Mutations not always are beneficial to the organism, in fact most of them are not and may have as consequence organisms leaving fewer descendants overtime. On the other hand, the mutations that are beneficial may provide enough diversity to survival and better fitness for an organism facing a changing environment [36]. In regard to SARS-CoV-2 some mutations have been the subject of particular interest especially those suspected to be associated with increased transmissibility and viral load.

The D614G was one of the first variants to be demonstrated potentially more contagious than previously circulating SARS-CoV-2. Among other less prominent genetic mutations, it presented an amino acid change in the spike protein caused by an A- to -G nucleotide mutation at position 23,403 in the Wuhan reference strain, the first strain that had its genome sequenced at the beginning of the pandemic [19,37]. In early March 2020, the G614 form was rarely detected globally but soon gained prominence in Europe and by May 2020 it already represented 78% of 12,194 global sequences analyzed [38]. Interestingly, the change from D614 to G614 occurred asynchronously in different regions throughout the world. SARS-CoV-2 bearing this mutation was associated with potentially higher viral loads in COVID-19 patients but not disease severity and in many countries was suspected to be related to the observed increase in the number of cases of infection.

The variant 20A.EU1, also known as A222V was reported in early summer 2020, presumably in Spain. It contains the A222V substitution located in the spike protein but far from the receptor binding site domain. Even though, it was suspected to affect the stability of the protein complex with a less pronounced effect than D614G based on its structural position [39]. Although it was under rise within Europe during the summer 2020, this variant did not significantly spread out of Europe.

Great concern was raised when the SARS-CoV-2 variant Y453F was repeatedly found in mink farms in Denmark, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States [40]. This mutation has been identified in more than 300 SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences isolated from humans across the globe. The finding of virus bearing this mutation in minks led Denmark authorities to order the culling of millions of minks over the concern of potential transmission to humans [41]. In fact, mink and other animals such as ferrets can be infected with SARS-CoV-2 and it raised the possibility that farmed-mink housed at high densities could pose an increased infection risk to humans. This hypothesis was supported considering that during virus amplification in these animals, natural selection may occur and eventually represent a potential risk to humans.

In the United Kingdom a variant known as 20I/501Y.V1, VOC 202012/01, or B.1.1.7 emerged possibly during September 2020 and presented many mutations including a 69/70 deletion and a P681H change, located near the S1/S2 spike protein subunits furin cleavage site, both seen many times in other variants as occurring spontaneously, and the N501Y. The latter mutation locates in the RBD region of the spike protein at position 501 where the amino acid asparagine has been replaced with tyrosine. This variant initially was detected in South East England but within a few weeks replaced other virus lineages in this geographical area and London and by December 2020 was identified across the United Kingdom during routine sampling and genomic tests [42]. Since its detection in UK, the presence of this variant has been reported in at least 31 countries around the world. Preliminary epidemiologic and modelling analysis suggest that this variant has increased transmissibility [43]. Also, it has been suggested that B.1.1.7 variant may be associated with increased risk of death compared to other variants, but this association has not been confirmed so far.

Another variant named 20H/501Y.V2 or B.1.351 seems to have emerged independently of B.1.1.7 in South Africa. It shares some mutations with the United Kingdom variant but presents new mutations such as K417N and E484K besides the N501Y. However, it lacks the deletion at 69/70 amino acids [44]. The three mutations mentioned for the South Africa variant are in the receptor binding site of spike protein and have shown to mildly increase receptor binding. Although there is no evidence that this variant may impact disease severity some studies have indicated that the E484K mutation may affect neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies [16,45].

In addition, a novel variant that has raised interest from epidemiological point of view was named P.1 but it is also known as 20J/501Y.V3. It is derived from the lineage B.1.1.28 first reported in Japan in four travelers from Brazil during routine screening. This variant present three major mutation in the spike protein RBD region specifically K417T, E484K and N501Y. This variant has been reported in a cluster of cases identified in Manaus, the largest city in the Amazon region in Brazil [46]. It was estimated that about 76% of the population in this region had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus by October 2020. However, a surge in the number of COVID-19 hospitalizations occurred by January 2021 suggesting that the new P.1 variant could be responsible for this abrupt increase number of cases due to reinfection [47]. The P.1 variant was also suspected to have increased transmissibility. Furthermore, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil another variant named P.2 containing the E484K was also detected and suspected to have higher transmissibility [48].

A new coronavirus variant named B.1.526 was identified in New York and it was demonstrated that its frequency is increasing compared to other circulating variants in the region. B.1.526 carries the mutations E484K and S477N in the spike protein. While the first mutation has shown the potential to reduce the efficacy of neutralizing antibodies, diminishing the immune response, the second is suspected to affect the binding of the virus to the host cells favoring the infectivity [49]. Therefore, among thousands of SARS-CoV-2 variants identified so far, few have been the subject of concern given their increased circulation frequencies locally or globally as mentioned above. It will not be a surprise if new variants with different combinations of mutations still emerge for a while even during the mass vaccination, which could indicate a viral response to the selective pressure imposed by the acquired immunity (Figure 2). In fact, by July 7, 2021, the variant named B.1.617.2, first identified in India, became one of the variants of concern in different countries given its increase in frequency even in countries that had a high vaccination rate [50,51].

Figure 2: SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and main mutations identified on the spike protein (K417T, E484K, N501Y, D614G and del69/70) suspected to be associated to higher transmissibility, immunological escape and better environmental fitness. (Source: adapted from sequences available at Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data-GISAID database).

Re-infection and Co-infection Cases of COVID-19

Currently there is enough evidence to support that SARS-CoV-2 may re-infect individuals who have been infected before and recovered [10,47,52]. Recently, cases of co-infection also have been reported as well as possible genetic recombination events of different SARS-CoV-2 variants [53,54]. It is known that coronaviruses in general have relatively high recombination rates [55]. The role of recombination between different coronaviruses in the emergence of the new SARS-CoV-2 have been addressed in several studies [56,57]. However, few studies have been done to understand the occurrence of recombination within human hosts. Notwithstand, when host cells are co-infected with different variants or lineages of the same virus recombination events may occur. During the process of replication, the viral genomes can be reshuffled and combined before packaging and release from the infected cells. As result, these new virions may acquire different pathogenic properties. Although awaiting confirmation, recently it was reported evidence of a hybrid SARS-CoV-2 virus in United States as resulted from recombination of the B.1.1.7 variant and the B.1.429 variant originated in California. This hybrid virus carries the deletion 69/70 from B.1.1.7 and the substitution L452R found in B.1.429 variant and demonstrated to confer resistance to antibodies [58].

Implications of Virus Mutation for the COVID-19 Pandemic Control and Effectivity of Vaccines

One of the gold standard diagnostic tool for COVID-19 is the RT-PCR. Concerns related to some types of mutations include their possible effects on the performance of this diagnostic assay. The deletion at position 69/70del, part of the mutations found in the variant B.1.17 for instance, was found to affect the performance of some diagnostic PCR assays that use specifically the S-gene as target. However, most PCR assays in use worldwide use multiple viral targets and therefore the impact of the variant on diagnostics is not anticipated to be significant in this case. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of the nature of mutations in different variants to better understand their impact on these diagnostic assays to minimize the possibility of false-negative results and consequently underestimate the number of cases of COVID-19.

Generally, the increased frequency of new SARS-CoV-2 variants in a specific region indicates better fitness of the virus and may correlate to a better mechanism of escape from immune response. This does not necessarily mean more severity of disease but may confer higher rates of replication and transmissibility to the virus as demonstrated for some of the variants identified so far.

Additionally, the emerging of new SARS-CoV-2 variants has suggested that additional shots of modified vaccines may be needed after initial vaccination with some of the currently vaccines in use to protect against some variants in the future. Although, it is not clear yet if that is the case for the currently authorized vaccines in relation to the variants identified in United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil. However, it has been shown that SARS-CoV-2 harboring receptor-binding domain mutations such as K417N/T, E484K, and N501Y, were highly resistant to neutralization by antibodies present in sera from BNT162b2 (Pfizer- BioNTech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna Therapeutics) vaccine recipients [59]. Moreover, in a phase III trial investigating single dose of the Janssen JNJ-78436725 vaccine it was shown 66% efficacy rate in preventing COVID-19 in moderate-to-severe cases but only 57% in a group from South Africa where the variant B.1.351 correspond to 95% of the cases [60]. Another factor to be considered is regarding to the exact durability of the COVID-19 vaccines protection which is unknown at the moment.

Concluding Remarks

Based on genomic sequences analysis it is important to observe that all SARS-CoV-2 in circulation are extremely genetically similar to one another. Therefore, the emerging of new variants should be considered as subproducts of a natural process that occurs when viruses replicate at high rates as it happens during a pandemic. Limitation of virus transmissibility and spreading will significantly decrease the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in different hosts and consequently decrease the possibility of emergence of new mutations and variants. A variant may eventually become a new strain if the mutations that it carries confer an advantage to the virus that changes its features to a point that it cannot be recognized by antibodies that recognize other SARS-CoV-2 variants or change the clinical features of the infection. Notwithstand, virus tracking through genomic sequencing is pivotal to let us always one step ahead and ready to implement the necessary actions to improve the diagnostic tools and the efficacy of vaccines. This way we will be able to feel safer and more able to control the pandemic more effectively.

References

2. World Health Organization. Available at: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-mission-briefing-on-covid-19---12-march-2020. (Accessed on: september 24, 2020).

3. Bonifácio LP, Pereira AP, Araújo DC, Balbão VD, Fonseca BA, Passos AD, et al. Are SARS-CoV-2 reinfection and Covid-19 recurrence possible? A case report from Brazil. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2020 Sep 18; 53.

4. Duggan NM, Ludy SM, Shannon BC, Reisner AT, Wilcox SR. Is novel coronavirus 2019 reinfection possible? Interpreting dynamic SARS-CoV-2 test results. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2021 Jan 1; 39:256-e1.

5. Takeda CF, de Almeida MM, de Aguiar Gomes RG, Souza TC, de Lima Mota MA, de Góes Cavalcanti LP, et al. Case report: recurrent clinical symptoms of COVID-19 in healthcare professionals: a series of cases from Brazil. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020 Nov;103(5):1993.

6. To KK, Hung IF, Ip JD, Chu AW, Chan WM, Tam AR, et al. COVID-19 re-infection by a phylogenetically distinct SARS-coronavirus-2 strain confirmed by whole genome sequencing. Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2020 Aug 25.

7. Gousseff M, Penot P, Gallay L, Batisse D, Benech N, Bouiller K, et al. Clinical recurrences of COVID-19 symptoms after recovery: viral relapse, reinfection or inflammatory rebound? Journal of Infection. 2020 Nov 1; 81(5):816-46.

8. Van Elslande J, Vermeersch P, Vandervoort K, Wawina-Bokalanga T, Vanmechelen B, Wollants E, et al. Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 reinfection by a phylogenetically distinct strain. Clin Infect Dis. 2020 Sep 5;10.

9. Prado-Vivar B, Becerra-Wong M, Guadalupe JJ, Marquez S, Gutierrez B, Rojas-Silva P, et al. COVID-19 Re-Infection by a Phylogenetically Distinct SARS-CoV-2 Variant, First Confirmed Event in South America. First Confirmed Event in South America.(September 3, 2020). 2020 Sep 3.

10. Tillett RL, Sevinsky JR, Hartley PD, Kerwin H, Crawford N, Gorzalski A, et al. Genomic evidence for reinfection with SARS-CoV-2: a case study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2021 Jan 1;21(1):52-8.

11. Dos Santos WG. Impact of virus genetic variability and host immunity for the success of COVID-19 vaccines. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2021 Jan 12:111272.

12. Röltgen K, Powell AE, Wirz OF, Stevens BA, Hogan CA, Najeeb J, et al. Defining the features and duration of antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection associated with disease severity and outcome. Science Immunology. 2020 Dec 7;5(54).

13. Long QX, Tang XJ, Shi QL, Li Q, Deng HJ, Yuan J, et al. Clinical and immunological assessment of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nature Medicine. 2020 Aug; 26(8):1200-4.

14. Robbiani DF, Gaebler C, Muecksch F, Lorenzi JC, Wang Z, Cho A, et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020 Aug; 584(7821):437-42.

15. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020 Aug 20; 182(4):812-27.

16. Weisblum Y, Schmidt F, Zhang F, DaSilva J, Poston D, Lorenzi JC, et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. Elife. 2020 Oct 28; 9:e61312.

17. Naqvi AA, Fatima K, Mohammad T, Fatima U, Singh IK, Singh A, et al. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2020 Oct 1; 1866(10):165878.

18. Michel CJ, Mayer C, Poch O, Thompson JD. Characterization of accessory genes in coronavirus genomes. Virology Journal. 2020 Dec; 17(1):1-3.

19. Lu R, Zhao X, Li J, Niu P, Yang B, Wu H, et al. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. The lancet. 2020 Feb 22; 395(10224):565-74.

20. Paraskevis D, Kostaki EG, Magiorkinis G, Panayiotakopoulos G, Sourvinos G, Tsiodras S. Full-genome evolutionary analysis of the novel corona virus (2019-nCoV) rejects the hypothesis of emergence as a result of a recent recombination event. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2020 Apr 1; 79:104212.

21. Schoeman D, Fielding BC. Coronavirus envelope protein: current knowledge. Virology Journal. 2019 Dec; 16(1):1-22.

22. Yan R, Zhang Y, Li Y, Xia L, Guo Y, Zhou Q. Structural basis for the recognition of SARS-CoV-2 by full-length human ACE2. Science. 2020 Mar 27; 367(6485):1444-8.

23. Ou X, Liu Y, Lei X, Li P, Mi D, Ren L, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nature Communications. 2020 Mar 27; 11(1):1-2.

24. Graham RL, Sparks JS, Eckerle LD, Sims AC, Denison MR. SARS coronavirus replicase proteins in pathogenesis. Virus Research. 2008 Apr 1; 133(1):88-100.

25. Narayanan K, Huang C, Lokugamage K, Kamitani W, Ikegami T, Tseng CT, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 suppresses host gene expression, including that of type I interferon, in infected cells. Journal of Virology. 2008 May 1; 82(9):4471-9.

26. Narayanan K, Ramirez SI, Lokugamage KG, Makino S. Coronavirus nonstructural protein 1: Common and distinct functions in the regulation of host and viral gene expression. Virus Research. 2015 Apr 16; 202:89-100.

27. Ogando NS, Zevenhoven-Dobbe JC, van der Meer Y, Bredenbeek PJ, Posthuma CC, Snijder EJ. The enzymatic activity of the nsp14 exoribonuclease is critical for replication of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Virology. 2020 Nov 9; 94(23):e01246-20.

28. Hillen HS, Kokic G, Farnung L, Dienemann C, Tegunov D, Cramer P. Structure of replicating SARS-CoV-2 polymerase. Nature. 2020 Aug; 584(7819):154-6.

29. Liu S, Shen J, Fang S, Li K, Liu J, Yang L, et al. Genetic spectrum and distinct evolution patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Frontiers in Microbiology. 2020 Sep 25; 11:2390.

30. Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data-GISAID. Over 151,000 viral genomic sequences of hCoV-19 shared with unprecedented speed via GISAID. Available at https://www.gisaid.org/ (Accessed July 7, 2021).

31. Elbe S, Buckland‐Merrett G. Data, disease and diplomacy: GISAID's innovative contribution to global health. Global Challenges. 2017 Jan; 1(1):33-46.

32. Shu Y, McCauley J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data–from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance. 2017 Mar 30; 22(13):30494.

33. Forster P, Forster L, Renfrew C, Forster M. Phylogenetic network analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2020 Apr 28; 117(17):9241-3.

34. Wu A, Peng Y, Huang B, Ding X, Wang X, Niu P, et al. Genome composition and divergence of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) originating in China. Cell Host & Microbe. 2020 Mar 11; 27(3):325-8.

35. van Dorp L, Acman M, Richard D, Shaw LP, Ford CE, Ormond L, et al. Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2020 Sep 1; 83:104351.

36. Duffy S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS biology. 2018 Aug 13; 16(8):e3000003.

37. Hou YJ, Chiba S, Halfmann P, Ehre C, Kuroda M, Dinnon KH, et al. SARS-CoV-2 D614G variant exhibits efficient replication ex vivo and transmission in vivo. Science. 2020 Dec 18; 370(6523):1464-8.

38. Korber B, Fischer WM, Gnanakaran S, Yoon H, Theiler J, Abfalterer W, et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell. 2020 Aug 20; 182(4):812-27.

39. Hodcroft EB, Zuber M, Nadeau S, Crawford KH, Bloom JD, Veesler D, et al. Emergence and spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. MedRxiv. 2020 Jan 1. Nov 27:2020.10.25.20219063.

40. Hammer AS, Quaade ML, Rasmussen TB, Fonager J, Rasmussen M, Mundbjerg K, et al. SARS-CoV-2 transmission between mink (Neovison vison) and humans, Denmark. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2021 Feb; 27(2):547.

41. Larsen HD, Fonager J, Lomholt FK, Dalby T, Benedetti G, Kristensen B, et al. Preliminary report of an outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in mink and mink farmers associated with community spread, Denmark, June to November 2020. Eurosurveillance. 2021 Feb 4; 26(5):2100009.

42. Rambaut A, Loman N, Pybus O, Barclay W, Barrett J, Carabelli A, et al. Preliminary genomic characterisation of an emergent SARS-CoV-2 lineage in the UK defined by a novel set of spike mutations. Virological.Org (2020).

43. Washington NL, Gangavarapu K, Zeller M, Bolze A, Cirulli ET, Barrett KM, et al. Genomic epidemiology identifies emergence and rapid transmission of SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.1.7 in the United States. MedRxiv. 2021 Jan 1.

44. Tegally H, Wilkinson E, Giovanetti M, Iranzadeh A, Fonseca V, Giandhari J, et al. Emergence and rapid spread of a new severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) lineage with multiple spike mutations in South Africa. MedRxiv. 2020 Jan 1.

45. Hu J, Peng P, Wang K, Fang L, Luo FY, Jin AS, et al. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants reduce neutralization sensitivity to convalescent sera and monoclonal antibodies. Cellular & Molecular Immunology. 2021 Apr; 18(4):1061-3.

46. National Institute of Infectious Diseases. Japan. Brief report: new variant strain of SARS-CoV-2 identified in travelers from Brazil. 2021 Jan 21 Available at: https://www.niid.go.jp/niid/images/epi/corona/covid19-33-en-210112.pdf

47. Sabino EC, Buss LF, Carvalho MP, Prete CA, Crispim MA, Fraiji NA, et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. The Lancet. 2021 Feb 6; 397(10273):452-5.

48. Naveca F, da Costa C, Nascimento V, Souza V, Corado A, Nascimento F, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reinfection by the new Variant of Concern (VOC) P. 1 in Amazonas, Brazil. Virological.org. 2021.

49. Annavajhala MK, Mohri H, Zucker JE, Sheng Z, Wang P, Gomez-Simmonds A, Ho DD, Uhlemann AC. A novel SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern, B. 1.526, identified in New York. medRxiv. 2021 Feb 25; 2021.02.23.2125225.

50. World Health Organization. COVID-19 weekly epidemiological update, edition 45, 22 June 2021.

51. Campbell F, Archer B, Laurenson-Schafer H, Jinnai Y, Konings F, Batra N, et al. Increased transmissibility and global spread of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern as at June 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021 Jun 17; 26(24):2100509.

52. Resende PC, Bezerra JF, Vasconcelos R, Arantes I, Appolinario L, Mendonça AC, et al. Spike E484K mutation in the first SARS-CoV-2 reinfection case confirmed in Brazil, 2020. Virological [Internet]. 2021 Jan; 10.

53. Hashim HO, Mohammed MK, Mousa MJ, Abdulameer HH, Alhassnawi AT, Hassan SA, et al. Infection with different strains of SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Archives of Biological Sciences. 2020 Dec 25; 72(4):575-85.

54. da Silva Francisco Jr R, Benites LF, Lamarca AP, de Almeida LG, Hansen AW, Gularte JS, et al. Pervasive transmission of E484K and emergence of VUI-NP13L with evidence of SARS-CoV-2 co-infection events by two different lineages in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Virus Research. 2021 Apr 15; 296:198345.

55. Su S, Wong G, Shi W, Liu J, Lai AC, Zhou J, et al. Epidemiology, genetic recombination, and pathogenesis of coronaviruses. Trends in Microbiology. 2016 Jun 1; 24(6):490-502.

56. Zhu Z, Meng K, Meng G. Genomic recombination events may reveal the evolution of coronavirus and the origin of SARS-CoV-2. Scientific Reports. 2020 Dec 10;10(1):1-0.

57. Neches RY, McGee MD, Kyrpides NC. Recombination should not be an afterthought. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2020 Nov; 18(11):606-.

58. Lawton G. Two variants have merged into heavily mutated coronavirus. Available at: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2268014-exclusive-two-variants-have-merged-into-heavily-mutated-coronavirus/ (Acessed on: February 25, 2021).

59. Garcia-Beltran WF, Lam EC, Denis KS, Nitido AD, Garcia ZH, Hauser BM, et al. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants escape neutralization by vaccine-induced humoral immunity. MedRxiv. 2021 Feb 18;2021.02.14.21251704

60. National Institute of Health. Janssen Investigational COVID-19 Vaccine: Interim Analysis of Phase 3 Clinical Data Released available at: https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/janssen-investigational-covid-19-vaccine-interim-analysis-phase-3-clinical-data-released