Abstract

Background: Obesity, which is increasing world-wide results from an interaction of genetic and environmental factors. Monogenic obesity which is rare is currently identified by gene sequencing. Drug therapy is available for these specific subsets of genetic obesity.

Aim: To identify MC4R mutations in obese subjects presenting to an obesity center in southern India.

Methods: Twenty consecutive subjects with obesity underwent sequencing for MC4R gene along with other routine biochemical parameters.

Results: Among 20 subjects, two were shown to have MC4R gene mutants. Both were women, with a body mass index above 40 (Class 3 obesity).

Conclusion: MC4R mutations in subjects with Class 3 obesity were reported from southern India.

Keywords

Syndromic obesity, Mutation, Diagnosis, Screening, Setmelanotide, Price, Accessibility

Core tip

Genetic causes of obesity are rare; unless genetic testing is done early, diagnosis may be delayed until adulthood. We report two women with Class 3 obesity who had mutations of MC4R.

Introduction

Obesity, an excess deposition of adipose tissue results from an interplay of genetics, lifestyle and environment. A mismatch of energy intake, expenditure and storage underlies its etiology [1,2]. The most common form of obesity is polygenic in which there is a complex interaction of many genes and the environment, including lifestyle. Appetite is controlled by satiety signals such as GLP-1, CCK, GIP and PYY from the intestines, leptin from adipose tissue and amylin from the pancreas; satiety signals are counterbalanced by the hunger hormone ghrelin. These can be prevailed over by hedonic responses which refer to a desire to eat food for pleasure.

Monogenetic forms of obesity are uncommon, representing less than 5% of cases, depending on the population. They generally present in childhood, but the diagnosis may be delayed until adulthood as we report here. Unlike syndromic forms of obesity with distinct clinical phenotypes due to chromosomal abnormalities or point mutations, non-syndromic forms often result from mutations or structural variants in genes of the leptin/melanocortin pathway [3]. Dissection of genetic contributions to obesity can provide insights into its pathogenesis and possible therapeutic interventions.

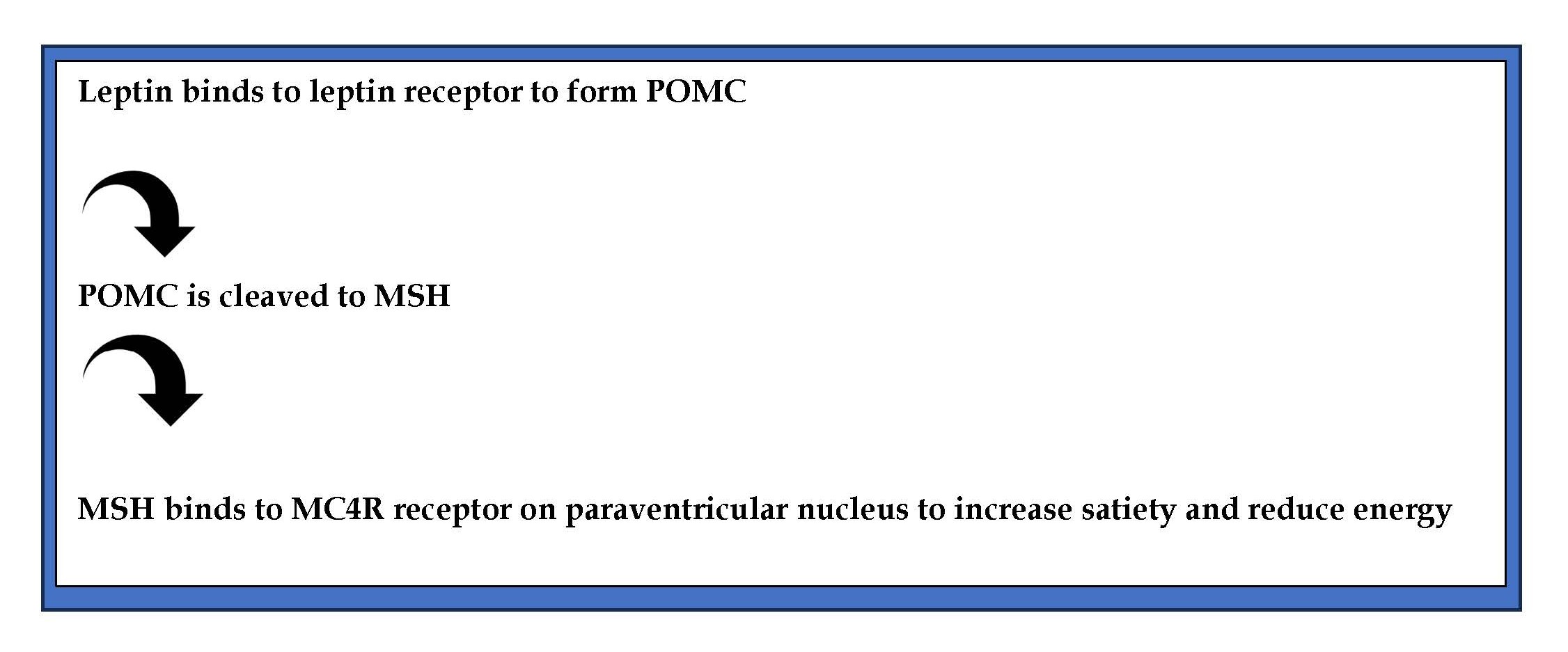

The peripheral signals of hunger reach the central nervous system where the hypothalamic leptin-melanocortin pathway ultimately maintains the balance between energy intake and expenditure. The hormone leptin activates the release of melanocortin ligands a and b from proopiomelanocortin (POMC). The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) is activated by the b melanocyte-stimulating hormone (MSH), leading to reduced hunger and increased expenditure of energy (Figure 1). Variants of MC4R result in obesity, beginning early in life. Localized in chromosome 18q22 of the many genes associated with body weight and obesity, MC4R is important. It is mainly expressed in the thalamus, hypothalamus and hippocampus.

Figure 1. Pathway of MC4R action.

After binding to MC4R, adenylate cyclase is activated via G protein (guanine nucleotide-binding protein), and a series of steps follow resulting in regulation of food intake and energy expenditure [2]. A variety of MC4R mutants were shown to result in obesity [4]. Recent studies have shown that variant MC4R rs17782313 gene increases appetite and energy intake [5] leading to obesity [6]. Knowledge of such mutations may may open new areas for developing personalized diets to prevent and treat obesity and its comorbidities [7].

Case series were reported on genetic variants leading to obesity not only from Western countries, but from the Arab world and India [8,9]. The cohort from northern India comprised a retrospective analysis of the medical records of children presenting with obesity below the age of five (n:7); one subject had homozygous nonsense variation in exon 1 of the MC4R gene [9].

In the present study we assessed MC4R gene for mutations in 20 consecutive adult subjects who presented to the Obesity and Diabetes Center at Visakhapatnam, southern India.

Materials and Methods

Study population and data collection

Obesity was diagnosed on the basis of WHO criteria [body mass index (BMI)]. Subjects tried and failed to control their body weight by following a schedule of diet, lifestyle modifications; some had taken commonly prescribed anti-obesity agents intermittently (often, metformin and lipase inhibitors; the newer generation of GLP-1 and GIP receptor agonists were not yet available in the Indian market at the time of the study). Majority of subjects presented primarily for cosmetic and obesity-related symptoms, not for metabolic disturbances. In view of the small sample size of this exploratory study, statistical analysis was not carried out. The mean and standard deviations are presented of the control group (Table 1). The study was approved by the Institutional Ethical Committee; all patients gave written informed consent before the study.

|

Variable |

Mean (SD) |

|

BMI |

31.29 (3.66) |

|

BMR |

1,504.78 (174.89) |

|

Body fat (%) |

35.17 (5.72) |

|

Visceral fat (%) |

14.67 (2.79) |

|

Muscle mass (%) |

23.22 (3.73) |

|

Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

173.61 (20.12) |

|

HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) |

46.00 (10.26) |

|

LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) |

82.14 (12.41) |

Isolation of genomic DNA from blood samples

Blood (stored in EDTA) were resuspended in 15 ml polypropylene centrifuge tubes with 3 ml of nuclei lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-Hcl, 400 mM Nacl and 2mM Na2 EDTA, P.H-8.2). The cell lysates were digested overnight at 37°C with 0.2 ml of 10% SDS and 0.5 ml of a Proteinase K solution (1 mg Proteinase K in 1% SDS and 2 mM Na2 EDTA). After digestion was complete, 1 ml of saturated Nacl (approximately 6 M) was added to each tube and shaken vigorously for 15 seconds, followed by centrifugation at 250 rpm for 15 minutes. The precipitation protein pellet was left at the bottom of the tube and the supernatant containing the DNA was transferred to another 15 ml poly propylene tube. Exactly 2 volumes of absolute ethanol was added and the tubes inverted several times until the DNA was precipitated. The DNA strands were removed with plastic spatula or pipette and transferred to a 1.5 ml micro centrifuge tube containing 100-200pl TE buffer (10Mm Tris –Hcl, 0.2mM Na2 EDTA, P.H-7.5). The DNA was allowed to dissolve for 2 hours at 37°C before quantification.

Polymerase chain reaction

PCR was performed in a LARK machine. Thin walled 0.2 ml tubes were used for amplification. A typical PCR reaction (20 μl) included 10.2 μl of autoclaved milliQ water , 2 μl of 10x PCR buffer (containing 750 Mm Tris-Hcl (P.H-8.8 at 25°C), 200 mM (NH4)2SO4, 0.1% Tween-20), 2 μl of dNTP mix (containing 2 mM of dNTP), 1.6 μl Mgcl2 ( final concentration 2 mM, where the concentration was kept to 1.5 mM), 0.8 μl (20 Pmol) of forward primer as well as reverse primer and 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (5U /μl) and 2.5 μl of template DNA.

Primers for MC4R gene

F-5’ATGGAGGGTGCTACGAGCAACT3’

R-5’TCTGTACTGTTTAATAGGGTGTTG3’

The amplification conditions were; one cycle of 94oC for 5 min followed by 30 cycles of 94oC for 30 sec, annealing at 500oC (temperature depending on TM value for a set of primers) for 1 min, extension at 72oC for 1 min and finally cool down to 4oC. Volume of template DNA used (2.5 μl; ~ 62 ng) worked fine for PCR amplification. The sample containing all reagents except template DNA was treated as the negative control. The size and the integrity of products was checked by electrophoresis. 10 μl of the PCR product was run on a 0.8–1.2% agarose gel at 5v/cm for an appropriate time period.

Purification of PCR amplified fragments

The PCR amplified product was transferred into a 1.5 ml centrifuge tube and the volume made up to 100 μl with T10E1. It was extracted with an equal volume of chloroform: isoamyl alcohol (v/v (24:1)). The aqueous phase was precipitated with 3 m sodium acetate (P.H-5.2), absolute ethanol and glycogen (USB) (to final 51 concentration of 500 ng) and twice the volume of ethanol at -80°C. This was centrifuged at full speed in biofuge at 4 oC. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol (full speed, 5min) air dried and suspended in 25-30 μl of autoclaved milliQ water. The amplified products were digested by restriction enzyme HincII. The digested DNA fragments were analyzed on 4% agarose gel.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

The agarose concentrations used in the electrophoretic separation of DNA to be resolved. Agarose was melted in 0.5xTBE (45mM Tris-borate and 1mM EDTA, pH-8.0) by heating and was cooled to about 500 oC before adding 0.5 μg/ml of Ethidium Bromide. The molten agarose was poured into a gel tray with combs in place and allowed to solidify. DNA samples were loaded in 1x gel loading buffer and electrophorosed at 302 nm using UV transilluminator.

Sequencing

Sequencing reactions were performed with the Applied Biosystem3500 genetic analyzer at BioAxis DNA Research Center. Hyderabad. We genotyped the G→A (valine to isoleucine) substitution at codon 103 of the MC4R gene (rs2229616), obtained with TaqMan chemistry (Applied Biosystems, model 3500). The percentage of each cohort successfully genotyped was 98·0%, 86·5%, and 97·3% respectively.

Results

Among the twenty individuals who were recorded to be obese when studied at various parameters, two female subjects aged 32 and 59 years (S nos 3,4. Table 2) had BMI of 42.7 and 46.2 respectively. Other data (BMI, BMR, Body fat, Visceral fat, Muscle fat, Total Cholesterol, HDL, LDL, VLDL, and TGL) are presented in Table 2.

|

S.NO |

Sex/age |

Obese class |

BMI |

BMR |

Body fat (%) |

Visceral fat (%) |

Muscle mass (%) |

Total Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

VLDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) |

TGL (mg/dl) |

|

01 |

F/42 |

1 |

29.1 |

1,313 |

38.0 |

11 |

21.9 |

185 |

46 |

91 |

48 |

240 |

|

02 |

M/35 |

2 |

31.8 |

1,749 |

28.7 |

18 |

28.9 |

178 |

62 |

83.8 |

32.2 |

161 |

|

03 |

F/59 |

4 |

42.7 |

1,811 |

46.3 |

30 |

19.7 |

152 |

38 |

86.4 |

27.6 |

138 |

|

04 |

F/32 |

4 |

46.2 |

1,983 |

47.3 |

30 |

19.0 |

138 |

46 |

72.4 |

19.6 |

98 |

|

05 |

M/57 |

1 |

29.4 |

1,638 |

34.7 |

19 |

25.4 |

178 |

48 |

93.2 |

36.8 |

184 |

|

06 |

F/29 |

2 |

31.1 |

1,342 |

28.4 |

16 |

28.4 |

142 |

42 |

57.8 |

42.2 |

211 |

|

07 |

F/42 |

1 |

28.4 |

1,431 |

37.4 |

10 |

23.1 |

159 |

58 |

79.8 |

21.2 |

106 |

|

08 |

F/40 |

3 |

37.2 |

1,824 |

32.1 |

13 |

21 |

162 |

38 |

64.2 |

59.8 |

299 |

|

09 |

M/26 |

1 |

25.1 |

1,408 |

26.4 |

16 |

24.4 |

145 |

48 |

80.4 |

16.6 |

83 |

|

10 |

F/35 |

2 |

30.9 |

1,417 |

40.9 |

13 |

21.1 |

186 |

52 |

93.6 |

40.4 |

202 |

|

11 |

M/49 |

2 |

31.4 |

1,811 |

29.1 |

20 |

28.9 |

189 |

39 |

103.6 |

46.4 |

232 |

|

12 |

F/31 |

2 |

33.4 |

1,476 |

40.5 |

15 |

21.4 |

159 |

58 |

80.8 |

20.2 |

101 |

|

13 |

M/44 |

3 |

36.1 |

1,782 |

43.2 |

18 |

18.4 |

186 |

58 |

102.4 |

16.6 |

184 |

|

14 |

F/34 |

2 |

30.9 |

1,417 |

40.9 |

13 |

24 |

164 |

52 |

79.6 |

40.4 |

204 |

|

15 |

F/24 |

1 |

26.2 |

1,358 |

36.8 |

14 |

21 |

152 |

44 |

56.4 |

24.2 |

128 |

|

16 |

M/22 |

2 |

32 |

1,384 |

29.4 |

16 |

19.6 |

144 |

38 |

58.4 |

26.4 |

148 |

|

17 |

F/28 |

1 |

26 |

1,398 |

26.8 |

12 |

29.8 |

178 |

18 |

82.4 |

38.2 |

145 |

|

18 |

F/56 |

3 |

38 |

1,824 |

39.8 |

14 |

18 |

190 |

49 |

82.4 |

42.6 |

232 |

|

19 |

M/58 |

2 |

34 |

1,468 |

40.2 |

13 |

22 |

210 |

46 |

97.4 |

38.2 |

202 |

|

20 |

M/53 |

2 |

34.3 |

1,446 |

39.8 |

13 |

21.8 |

198 |

52 |

89.8 |

32.6 |

184 |

In the gene sequencing studies among the obese individuals codon 103 on MC4R gene was found to be mutated. Replacement of guanine with adenosine resulted in a mutated MC4R gene product (isoleucine in the place of valine, indicating that a mutation occurred in the triplet code where adenosine replaced guanine resulting in a mutated form of MC4R gene product.

The mutant MC4R protein structure was predicted by MODELLAR software image.

The mutant MC4R protein structure was validated in ProSA-web and Procheck values determined.

The given sequence was identified as Homo sapiens melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R),

RefSeqGene on chromosome 18

Score: 776 bits(420)

Identities: 420/420(100%)

Discussion

In the present study, we identified two subjects with MC4R gene mutation among twenty consecutive patients who were screened for the gene mutation in Obesity and Diabetes Center in southern India. While the prevalence of MC4R mutations was assessed in large samples from western countries, to our knowledge there is only one other report of MC4R mutation from India [6].

Most studies on MC4R mutations were done in childhood obesity. There is a report from Paolini et al. who showed mutants of MC4R, leptin and leptin receptor were identified in adults with morbid obesity who underwent bariatric surgery. Access to genetic testing was limited in India until recently. It is possible that childhood obesity was considered a passing phase, which would go away as the child grows; awareness of monogenic obesity among treating physicians may be poor. Most Indians do not have insurance which covers these expensive tests and may have therefore not been screened. The current sample was screened without their having to pay, as part of a project. This also explains the limited sample size (n:20).

The MC4R agonist drug setmelanotide can be effective in adults with monogenic obesity [10,11].

In a German cohort (n:899) of children with obesity who were screened in a pediatric outpatient clinic, heterozygous variants of the coding region in MC4R gene were identified in 2.45% (n:22). The prevalence was comparable to pediatric cohorts from other centers which ranged from 0.5% to 5.8% [1]. In an earlier German cohort of obese children (n:510), mutations in MC4R gene were detected in 1.2% [12]. A comparable prevalence of 2.4% was observed in a cohort of obese Czech children (n:289) [13]. Similar prevalence was found in reports from Spain [14] and Denmark [15]. Mutations of MC4R gene as a cause of obesity was reported from Austria as a case report [16] and from China [17]. Mutant MC4R genes were observed among adults with varying phenotypes [18,19].

MC4R mutations were the first to be observed in animal models, where a gene dosage effect was shown [20]; occurrence of a mutation must be supported by additional evidence to imply its causation in obesity. A number of subclassifications of MR4R mutations were proposed [2]. The clinical manifestations take the form of obesity, hyperphagia and metabolic abnormalities.

Until recently, there was no specific treatment for obesity caused by MC4R mutations. Lifestyle measures alone lead to poor outcomes. Therefore, screening guidelines for the condition were not available. With the availability of pharmacological agents such as setmelanotide, which specifically act on the melanocorticotropin system [21] to control obesity, guidelines are likely to be modified to include screening for mutations [2].

Setmelanotide, an MC4R agonist, has been approved to treat obesity due to MC4R mutations. Studies in animal models (Bischof et al. 2016) [22], showed that it had the potential to be used as a replacement therapy for rare syndromic forms of obesity due to impaired POMC neuronal function. Coulter et al. [23] suggested that it could be used to treat obesity resulting from POMC system mutations. Unlike earlier agents, setmelanotide had a favorable therapeutic index without adverse effects on the heart and blood pressure. The use of setmelanotide was included in the statement published in ‘The Anti-Obesity Medications and Investigational Agents: An Obesity Medicine Association Clinical Practice Statement’ (Bays et al. 2022) [24]. Side effects, observed after subcutaneous route of the drug comprise injection site reactions, skin hyperpigmentation, gastrointestinal disturbances, depression and rarely, spontaneous penile erection [2].

The efficacy of setmelanotide in monogenic childhood obesity is established [25]. In a comparative analysis on the effectiveness of semaglutide, liraglutide, orlistat, and phentermine for weight loss in obesity, semaglutide was most efficient in inducing weight loss and had additional cardiometabolic benefits. Liraglutide is less potent and requires daily injection. Phentermine has short-term benefits but has concerns about dependency and cardiovascular risks. Orlistat results in modest weight loss at the cost of gastrointestinal side effects which may affect adherence. The authors concluded semaglutide is the preferred option for significant and sustained weight loss in properly screened and selected obese subjects [26].

Our study has inherent limitations of an explorative study due to limitations on screening facilities and the cost of testing. The results from this small sample from a single center must be expanded by recruiting a larger sample and a more comprehensive family tree construction, phenotypic and genotype sequencing as well as functional validation of the mutations.

Here we document MC4R mutations in a population from southern India who presented to the Obesity and Diabetes Center. Limitations in identifying mutations causing obesity include the price of gene testing, which is often borne out of pocket expenses by the patient’s family. In addition, the cost of medication, viz setmelanotide is also likely to be a deterrent for those who need it.

Nevertheless, setmelanotide is a specific agent that is available for treatment of obesity due to mutations of the POMC system. Potential agents that could enter the market include not only MC4R agonists and antagonists, but also inverse agonists which are under investigation such as AgRP and its mimics for MC4R [27,28].

Our findings highlight the need for awareness of monogenic obesity in Indian populations, and the importance of considering genetic testing in selected patients with class 3 obesity, despite barriers of cost and accessibility. Identification of mutations early in life allows proper drug therapy in childhood, which would avoid the complications of adiposity at an early stage.

Conclusion

We report two adult women with class 3 obesity who harbored mutation of MC4R gene from southern India. Left undiagnosed, mutants may be identified in adulthood. Issues of accessibility to gene sequencing and cost constraint of drugs are limitations.

Author Contributions

Subha S designed and conducted the study and wrote the paper; GR Sridhar and Lakshmi G designed the study and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgements

Institutional review board statement

This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of King George Hospital.

Informed consent statement

All patients gave written informed consent before the study.

Conflict-of-interest statement

All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

Data sharing statement

Dataset available from Senkula Subha (senkhula.subha@gmail.com).

References

2. Sridhar GR, Gumpeny L. Built environment and childhood obesity. World J Clin Pediatr. 2024 Sep 9;13(3):93729.

3. Reddon H, Guéant JL, Meyre D. The importance of gene-environment interactions in human obesity. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016 Sep 1;130(18):1571–97.

4. Bayhaghi G, Karim ZA, Silva J. Descriptive analysis of MC4R gene variants associated with obesity listed on ClinVar. Sci Prog. 2024 Oct–Dec;107(4):368504241297197.

5. Álvarez-Martín C, Caballero FF, de la Iglesia R, Alonso-Aperte E. Association of MC4R rs17782313 Genotype With Energy Intake and Appetite: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2025 Mar 1;83(3):e931–46.

6. Yu K, Li L, Zhang L, Guo L, Wang C. Association between MC4R rs17782313 genotype and obesity: A meta-analysis. Gene. 2020 Apr 5;733:144372.

7. Adamska-Patruno E, Bauer W, Bielska D, Fiedorczuk J, Moroz M, Krasowska U, et al. An Association between Diet and MC4R Genetic Polymorphism, in Relation to Obesity and Metabolic Parameters-A Cross Sectional Population-Based Study. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Nov 7;22(21):12044.

8. AbouHashem N, Al-Shafai K, Al-Shafai M. The genetic elucidation of monogenic obesity in the Arab world: a systematic review. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Apr 20;35(6):699–707.

9. George A, Navi S, Nanda P, Daniel R, Anand K, Banerjee S, et al. Clinical and molecular characterisation of children with monogenic obesity: a case series. Pediatr Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2024;30(2):104–09.

10. Ayers KL, Glicksberg BS, Garfield AS, Longerich S, White JA, Yang P, et al. Melanocortin 4 Receptor Pathway Dysfunction in Obesity: Patient Stratification Aimed at MC4R Agonist Treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jul 1;103(7):2601–2612.

11. Lazareva J, Brady SM, Yanovski JA. An evaluation of setmelanotide injection for chronic weight management in adult and pediatric patients with obesity due to Bardet-Biedl syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2023 Apr;24(6):667–674.

12. Melchior C, Schulz A, Windholz J, Kiess W, Schöneberg T, Körner A. Clinical and functional relevance of melanocortin-4 receptor variants in obese German children. Horm Res Paediatr. 2012;78(4):237–46.

13. Hainerová I, Larsen LH, Holst B, Finková M, Hainer V, Lebl J, et al. Melanocortin 4 receptor mutations in obese Czech children: studies of prevalence, phenotype development, weight reduction response, and functional analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Sep;92(9):3689–96.

14. Morell-Azanza L, Ojeda-Rodríguez A, Giuranna J, Azcona-SanJulián MC, Hebebrand J, Marti A, et al. Melanocortin-4 Receptor and Lipocalin 2 Gene Variants in Spanish Children with Abdominal Obesity: Effects on BMI-SDS After a Lifestyle Intervention. Nutrients. 2019 Apr 26;11(5):960.

15. Trier C, Hollensted M, Schnurr TM, Lund MAV, Nielsen TRH, Rui G, et al. Obesity treatment effect in Danish children and adolescents carrying Melanocortin-4 Receptor mutations. Int J Obes (Lond). 2021 Jan;45(1):66–76.

16. Rettenbacher E, Tarnow P, Brumm H, Prayer D, Wermter AK, Hebebrand J, et al. A novel non-synonymous mutation in the melanocortin-4 receptor gene (MC4R) in a 2-year-old Austrian girl with extreme obesity. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2007 Jan;115(1):7–12.

17. Rong R, Tao YX, Cheung BM, Xu A, Cheung GC, Lam KS. Identification and functional characterization of three novel human melanocortin-4 receptor gene variants in an obese Chinese population. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2006 Aug;65(2):198–205.

18. Stokić E, Djan M, Vapa Lj, Djan I, Plećas A, Srdić B. Polymorphism Val103Ile of the melanocortin-4 receptor gene in the Serbian population. Mol Biol Rep. 2010 Jan;37(1):33–7.

19. Hinney A, Bettecken T, Tarnow P, Brumm H, Reichwald K, Lichtner P, et al. Prevalence, spectrum, and functional characterization of melanocortin-4 receptor gene mutations in a representative population-based sample and obese adults from Germany. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 May;91(5):1761–9.

20. Huang J, Wang C, Zhang HB, Zheng H, Huang T, Di JZ. Neuroimaging and neuroendocrine insights into food cravings and appetite interventions in obesity. Psychoradiology. 2023 Oct 14;3:kkad023.

21. Ferraz Barbosa B, Aquino de Moraes FC, Bordignon Barbosa C, Palavicini Santos PTK, Pereira da Silva I, Araujo Alves da Silva B, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Setmelanotide, a Melanocortin-4 Receptor Agonist, for Obese Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Pers Med. 2023 Oct 4;13(10):1460.

22. Bischof JM, Van Der Ploeg LH, Colmers WF, Wevrick R. Magel2-null mice are hyper-responsive to setmelanotide, a melanocortin 4 receptor agonist. Br J Pharmacol. 2016 Sep;173(17):2614–21.

23. Coulter AA, Rebello CJ, Greenway FL. Centrally Acting Agents for Obesity: Past, Present, and Future. Drugs. 2018 Jul;78(11):1113-1132.

24. Bays HE, Fitch A, Christensen S, Burridge K, Tondt J. Anti-Obesity Medications and Investigational Agents: An Obesity Medicine Association (OMA) Clinical Practice Statement (CPS) 2022. Obes Pillars. 2022 Apr 15;2:100018.

25. Trapp CM, Censani M. Setmelanotide: a promising advancement for pediatric patients with rare forms of genetic obesity. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2023 Apr 1;30(2):136–140.

26. Patel JP, Hardaswani D, Patel J, Saiyed F, Goswami RJ, Saiyed TI, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Semaglutide, Liraglutide, Orlistat, and Phentermine for Weight Loss in Obese Individuals: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2025 Mar 10;17(3):e80321.

27. Fontaine T, Busch A, Laeremans T, De Cesco S, Liang YL, Jaakola VP, et al. Structure elucidation of a human melanocortin-4 receptor specific orthosteric nanobody agonist. Nat Commun. 2024 Oct 1;15(1):7029.