Abstract

Introduction: Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the most common gastrointestinal cancer and a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. Molecular indicators of pathogenic factors that regulate CRC, which are known as oncogenes, are desirable for response to treatment and improvement of CRC patient management. Several risk factors play a role in the development of this disease, which can occur genetically, familial, or sporadically. CRC tumorigenesis is stimulated by the proto-oncogene β-catenin (wnt/β-catenin). Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (c-Cbl) inhibits CRC tumor growth through an unknown mechanism that affects nuclear β-catenin. The current objective of this study is to evaluate the expression levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl genes to determine if their transcripts can be used as suitable diagnostic indicators. Additionally, we aim to investigate the correlation between clinicopathological information of CRC patients and the levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl.

Materials and Methods: Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) method was used to evaluate the expression levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl in 45 colorectal tumor tissues and 45 adjacent control tissues. Furthermore, we analyzed the diagnostic power of Cbl-b and c-Cbl by plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves.

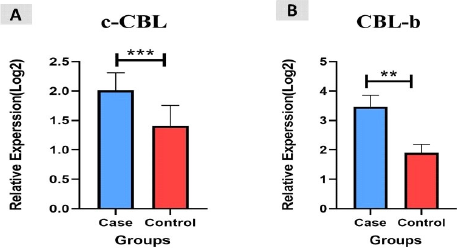

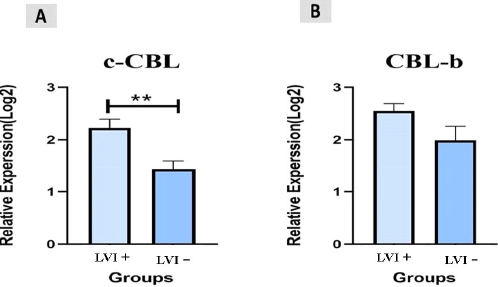

Results: Our results showed that the expression levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl were significantly increased in CRC patients compared to the adjacent control group (P<0.003, P<0.004). Analysis of clinicopathological features of CRC patients revealed that the expression of Cbl-b and c-Cbl was associated differently with TMN stage, LVI+ (P<0.0003, P<0.0001) (P<0.003, P<0.07).

Conclusion: These results indicate that the levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl may serve as potential diagnostic indicators for CRC.

Keywords

Colorectal cancer (CRC), c-Cbl, Cbl-b, Diagnostic biomarkers, Real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Introduction

The most prevalent gastrointestinal cancer is colorectal cancer (CRC), which is also one of the main causes of cancer-related mortality globally [1,2]. Given that cancer develops slowly from precancerous lesions, early discovery of the disease is critical as it improves prognosis when discovered in the early stages [3]. Therefore, early detection of the disease is critical. Despite the fact that numerous screening tests, including colonoscopy, have helped to reduce the risk of CRC-related death, there remains a significant variance in the incidence and mortality of CRC globally [4]. This disease can be inherited, familial, or sporadic, and a number of risk factors have led to its emergence [5]. When cancer progresses, the regulation of normal cell development and functions deteriorates. Several studies have focused on the many cell-intrinsic elements that regulate and modulate this process. Nonetheless, greater emphasis has been placed on the extrinsic factors that contribute to cancer growth and dissemination present in the tumor microenvironment. Also, the tumor microenvironment plays a crucial role in cancer growth and dissemination [3,6]. To effectively manage CRC patients, it is preferable to use biomarkers that can predict prognosis, disease recurrence, and therapy response. These biomarkers can be discovered in the molecular markers of pathogenic factors that regulate CRC carcinogenesis [7]. Large bowel tumors include a diverse variety of premalignant and malignant lesions, many of which can be removed endoscopically [3,8]. As a result, colon neoplasms can be avoided by intervening at various phases of carcinogenesis, which begins with the uncontrolled proliferation of epithelial cells and progresses to the creation of adenomas of various dimensions [9]. CRC treatment is becoming more customized, guided by a combination of clinical, neoplastic, and molecular factors [10]. Moreover, a series of histopathological degrees, and this progression can be caused by a sequence of genetic alterations in the cell, such as the activation of oncogenes and the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes [11].

The B-lineage lymphoma (Cbl) protein family is a subfamily of RING finger E3 ubiquitin ligases (RTKs) and is a prominent negative regulator of tyrosine kinases receptor [12]. Cbl proteins are negative regulators of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and can affect the sensitivity of cancer cells to certain drugs. A recent study found that when Casitas B-lineage lymphoma (c-Cbl) ubiquitinated estimated glomerular filtration rate (EGFR), CRC cells showed acquired resistance to cetuximab [13]. According to previous studies, Casitas B lymphoma-b (Cbl-b), the second member of the Cbl family, which controls the distribution of EGFR in lipid rafts, reduces the apoptosis produced by tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand, CD253 (TRAIL) [14]. However, it is still unknown if Cbl-b has a role in controlling the sensitivity of gastric cancer to cetuximab [12,13]. Beta proto-oncogene –catenin (wnt/β-catenin) has also been implicated in CRC carcinogenesis [15].

The role of c-Cbl in human CRC is still not well understood, but it has been found to target receptor tyrosine kinases like c-Met and nonreceptor tyrosine kinases like c-Src [16,17]. By reducing Wnt signaling and inhibiting nuclear catenin, c-Cbl reduces the development of colon cancer cells [18]. The expression of c-Cbl in colorectal cancers has been linked to the overall survival of stage IV CRC patients [19]. In this study, we aim to evaluate the expression levels of Cbl-b and c-Cbl as potential diagnostic biomarkers for CRC. We also aim to investigate the association of Cbl-b and c-Cbl with clinicopathological data of CRC patients.

Methods

Patients and samples

This case-control study collected tissue samples from patients referred to endoscopy, oncology, or surgery clinics from July 2020 to December 2022. Finally, 45 patient’s subjects were included, and the samples were collected either through biopsies or surgical resections. Moreover, matched control group specimens from CRC patients were collocated from tissue that contained no tumor cells and were physically adjacent (>2 cm apart) to the tumor site. The inclusion criteria age between 22 and 55 years old, and for the tumor tissue samples approved by a board-certified pathologist, the histological consistency of samples with colon adenocarcinoma and the patients have not received any CRC-associated therapy before the time of the biopsy. Subjects who received CRC-associated therapy, surgical resections, and any other malignancies were excluded from the study, as well as, their demographic, lifestyle, and histopathological information involving the clinical TNM staging was recorded.

Ethics statement

The study was compiled following the requirements approved by the Ethics Committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences, as well as informed written consent was obtained from all subjects before joining the study (Code No: IR.IUMS.REC.1400.1119).

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

The kit was used for RNA extraction (Cinna colon, Tehran, Iran). First, we homogenized each sample with a solution then added to a 2 ml tube containing 1 ml of ice-cold RNXTM-PLUS solution. The mixture was vortexed for 5-10 seconds and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes. Then, 200 μl of chloroform was added and mixed well by shaking for 15 seconds (without vortexing). The mixture was incubated on ice or at 4°C for 5 minutes. After that, it was centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes, and the aqueous phase was transferred to a new RNase-free 1.5 ml tube (without disturbing the mid-phase). An equal volume of isopropanol was added to the tube, mixed gently, and incubated on ice for 15 minutes. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12000 rpm at 4°C for 15 minutes, and the supernatant was discarded. Next, 1 ml of 75% ethanol was added to the tube and vortexed shortly to dislodge the pellet. The tube was then centrifuged at 40°C for 8 minutes at 7500 rpm. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was allowed to dry at room temperature for a few minutes (without letting it dry completely, as it would decrease the solubility of the pellet). The isolated RNA was eluted in 40 µl of RNase-free water. The concentration and integrity of the total RNA were assessed by measuring the A260/A280 using a nano Drop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The ratio for each sample was intended to be between 1.7 and 2.1. The RNA suspension was stored at -80°C for further analysis and then converted to cDNA. Reverse transcription reaction was performed using a cDNA kit (Cinna colon, Tehran, Iran), and cDNA was prepared from 2 μg of total RNA with Oligo(dT) and random hexamer primers. The kit mix was run on a PCR thermocycler gene as follows: 10 min at 25°C, 2 h at 37°C, 5 min at 85°C. The cDNA was diluted to a total concentration of 5 ng/μL.

Real-time PCR

Real-time PCR analysis was conducted in duplicates using 2.0X Real Q-PCR Master Mix with SYBR Green (Ampliqon, Odense, Denmark). Each sample reaction involved 10 µl of 2X Real Q-PCR Master Mix, 1 µl cDNA, 1 µl of each primer (10 mol/µl), and 8 µl of distilled water. Reactions were run on the Step One Plus Real-time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) using the thermal cycling parameters 95°C for 2 min and 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 30 s. Specificity of products was verified by melting curve analysis. Gene expression levels were normalized using the expression level of beta-2 macroglobulin (β2 M) as the housekeeping gene. Primers were designed and positioned in a variety of exon junctions of c-CBL and CBL-b to avoid false-positive results due to DNA contamination (Table 1).

|

Genes size (bp) |

Primers |

Sequences |

Amplicon |

|

CBL-b |

Forward primer |

TCACAGGACAGACGAAATCTCA |

93 |

|

Reverse primer |

CTGGAATTGACCATTGGGAAAGA |

||

|

c-CBL |

Forward primer |

TGGTGCGGTTGTGTCAGAAC |

81 |

|

Reverse primer |

GGTAGGTATCTGGTAGCAGGTC |

||

|

Beta-2-microglogulin |

Forward primer |

TGTCTTTCAGCAAGGACTGGT |

143 |

|

Reverse primer |

TGCTTACATGTCTCGATCCCAC |

Statistical analysis

Efficiency values and cycle threshold (Ct) for each sample were determined using the Lin Reg software (version: 2017.1), and the expression ratio (Fold change 2 -ΔΔ Ct) of c-Cbl and C bl-b were estimated using REST 2009 software. The statistical differences of c-CBL and CBL-b mRNA levels between patients and control subjects were analyzed with Graph Pad Prism software version 8.0 (La Jolla, CA) using the Mann-Whitney test and unpaired t-test. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

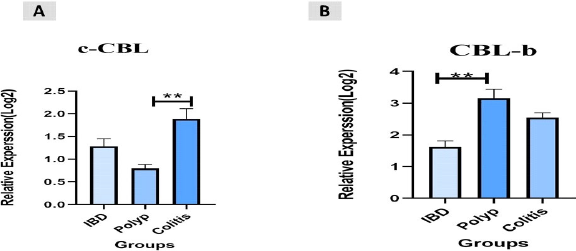

A total of 45 CRC patients (22 females and 23 males) aged between 22 and 55 years (mean ± SD = 43.91±9.73 years) were included in the study. Among the patients, 20 (45%) had colon cancer and 25 (55%) had rectal cancer. We measured the expression levels of c-Cbl and Cbl-b using qRT-PCR in CRC tissue and found that they were up-regulated in colorectal cancer tissues compared to controls (P<0.003, P<0.004, Figure 1). The retrospective review of patient records revealed that 11 (24.4%) CRC patients had inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), 15 (33.3%) had a polyp, and 19 (42.3%) had colitis. Additionally, based on clinical TNM staging, 27 (60%) patients were stage II, 12 (26.6%) were stage III, and 6 (13.4%) were stage IV. The expression of c-Cbl and Cbl-b was found to be associated with TNM stage (P<0.0003, P<0.0001). The stage IV group had up-regulated expression of c-Cbl compared to the stage II and III groups (stage II: 0.9% vs. 1.8%, stage III: 1.1% vs. 1.8%). Similarly, the stage IV group had up-regulated expression of Cbl-b compared to the stage II and III groups (stage II: 1.1% vs. 2.6%, stage III: 2.3% vs. 2.6%) (Figure 2). The clinical characteristics of the subjects included in the study are shown in Tables 2 and 3. ROC curve analysis showed that these genes may be useful biomarkers for distinguishing colorectal adenocarcinoma patients from control subjects. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) was larger, indicating a higher diagnostic value. The AUC for c-CBL and CBL-b expression levels is shown in Figure 3. In this study, lymph vascular invasion (LVI+) was observed in 10 (22%) of the 50 CRC cases. The expression of c-Cbl and Cbl-b was found to be associated with lymph vascular invasion (P<0.003, P<0.07), with the LVI+ group showing higher expression compared to the LVI- group (2.2% vs. 1.4%, 2.5% vs. 2.1%, Figure 4). Furthermore, the expression level of c-Cbl was found to be associated with a history of colitis in CRC patients and was up-regulated compared to the IBD and polyp groups (P<0.001). Similarly, the expression level of Cbl-b was associated with a history of polyps in CRC patients and was up-regulated compared to the IBD and colitis groups (P<0.001, Figure 5). These findings suggest that these genes may play a regulatory role in tumor progression.

Figure 1. The relative expression levels (−ΔCt) of c-CBL, CBL-b and β2M. A. shows the differences in c-CBL expression between all the study groups. B. shows the differences CBL-b expression between all the study groups. (***: P<0.003, **; P<0.004).

Figure 2. The relative expression levels (−ΔCt) of c-CBL and CBL-b levels. A. shows the differences in c-CBL levels between TMN stage in CRC patients. B. shows the differences in CBL-b levels between TMN stage in CRC patients. (P<0.0003, P<0.0001).

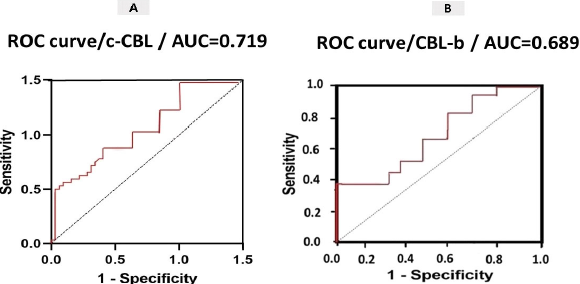

Figure 3. ROC curve analysis of the diagnostic value of CRC-related genes to distinguish between CRC patients and healthy individuals.

Figure 4. The relative expression levels (−ΔCt) of c-CBL and CBL-b levels. A. shows the differences in c-CBL levels between Lymph vascular invasion in CRC patients. B. shows the differences in CBL-b levels between Lymph vascular invasion in CRC patients. (**: P<0.003, P<0.07).

Figure 5. The relative expression levels (−ΔCt) of c-CBL and CBL-b levels. A. shows the differences in c-CBL expression between all the study groups. B. shows the differences in CBL-b expression between all the study groups. (p<0.001, p<0.001).

|

Variable |

Clinic pathological parameter |

Number of samples (n = 45) |

Mean ± SD |

p value |

|

Age |

≥ 45 |

24 |

14.63 ± 3.02 |

p<0.842 |

|

< 45 |

21 |

14.24 ± 4.37 |

||

|

Gender |

Male |

22 |

13.43 ± 1.24 |

p=0.786 |

|

Female |

23 |

13.47 ±2.82 |

||

|

TNM stage |

II |

27 |

8.42 ± 1.74 |

p<0. 0001 |

|

III |

12 |

15.79 ± 2.58 |

||

|

IIV |

4 |

16.32 ± 1.38 |

||

|

Tumor size |

<2 |

11 |

10.44 ± 4.53 |

p=0.07 |

|

2-3.5 |

12 |

15.21 ± 3.52 |

||

|

3.5-5 |

12 |

15.54 ± 2.23 |

||

|

>5 |

10 |

14.09 ± 3.38 |

||

|

Localization |

Colon |

20 |

11.25 ± 3.87 |

p=0.695 |

|

Rectum |

25 |

11.33 ± 2.89 |

||

|

Lymphatic invasion |

Positive |

10 |

12.77 ± 1.27 |

p<0.07 |

|

Negative |

35 |

12.82 ± 2.54 |

||

|

CRC: Colorectal Cancer; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis; LVI: Lymph Vascular Invasion |

||||

|

Variable |

Clinic pathological parameter |

Number of samples (n = 45) |

Mean ± SD |

p value |

|

Age |

≥ 45 |

24 |

12.87 ± 2.02 |

p<0.682 |

|

< 45 |

21 |

12.18 ± 3.37 |

||

|

Gender |

Male |

22 |

14.65 ± 2.34 |

p=0.576 |

|

Female |

23 |

14.47 ±3.72 |

||

|

TNM stage |

II |

27 |

7.52 ± 4.63 |

p<0.0003 |

|

III |

12 |

10.89 ± 2.48 |

||

|

IIV |

4 |

12.32 ± 3.36 |

||

|

Tumor size |

<2 |

11 |

11.84 ± 3.46 |

p=0.08 |

|

2-3.5 |

12 |

12.04 ± 3.42 |

||

|

3.5-5 |

12 |

12.07 ± 3.24 |

||

|

>5 |

10 |

9.09 ± 3.38 |

||

|

Localization |

Colon |

20 |

15.28 ± 3.90 |

p=0.595 |

|

Rectum |

25 |

15.35 ± 4.29 |

||

|

Lymphatic invasion |

Positive |

10 |

9.77 ± 2.26 |

p<0.003 |

|

Negative |

35 |

5.82 ± 3.64 |

||

|

CRC: Colorectal Cancer; TNM: Tumor-node-metastasis; LVI: Lymph Vascular Invasion |

||||

Discussion

Colorectal cancer (CRC) tumorigenesis is driven by the proto-oncogene β-catenin. c-Cbl inhibits CRC tumor growth via a poorly understood mechanism that targets nuclear β-catenin. In addition, nothing is known about the function of c-Cbl in human CRC. In order to better understand the mechanism of action of Cbl-b and c-Cbl in colorectal cancer, we looked at these gene expressions in 45 CRC patients.

The findings showed that different levels of c-Cbl and Cbl-b expression were related to different TNM stages (P<0.0003, P<0.0001). In another study, it was found that the levels of expression of c-Cbl, Cbl-b, and EGFR were found to be higher in the gastric carcinoma group compared to the control group (P<0.01). Moreover, there is a positive correlation between the expression of the Cbl-b gene and lymph node metastasis as well as TNM staging in gastric carcinoma (P<0.001). Also, the overexpression of c-Cbl, Cbl-b, and EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) genes are associated with the invasion and progression of gastric carcinoma. The study suggests that these genes may serve as potential biomarkers for gastric carcinoma, indicating their potential value in diagnosing and treating the disease [20]. Although, their potential roles in the development and metastasis of colorectal cancer (CRC) are not yet clearly understood. Our result show that, the expression levels of c-Cbl and Cbl-b were upregulated in colorectal cancer tissues as opposed to control tissues (P<0.003, P<0.004). This study displays the chosen clinical features of the participants. Using qRT-PCR, we evaluated the expression levels of c-Cbl and Cbl-b in CRC tissue. Kumaradevan et al. in 2017 found that c-Cbl, a negative regulator of CRC tumor growth, is associated with overall survival of patients with mCRC. This further validates the molecular features of c-Cbl, which are critical to its effect on nuclear β-catenin. Moreover, c-Cbl's ubiquitin ligase activity has been found to regulate several aspects of CRC, such as tumor growth and angiogenesis [21]. Moreover, c-Cbl's ubiquitin ligase activity has been found to regulate several aspects of CRC, such as tumor growth and angiogenesis. According to ROC curve research, the tissue may serve as a good biomarker to differentiate colorectal cancer patients from healthy individuals. The diagnostic value is higher when the area under the ROC curve (AUC) is larger. In accordance with our results, Cristóbal et al. by analyzing the c-Cbl expression at the colorectal cancer levels have shown that c-Cbl was up-regulated in a recurrent event in 8 out of 22 CRC patients, as evidenced by c-Cbl overexpression in the tumor samples compared to their paired normal colonic mucosa. Thus, c-Cbl deregulation could be a contributing factor to the acquisition of invasiveness properties of CRC cells and may represent a novel therapeutic target for a subset of CRC patients [22]. In the present study, LVI+ was found in 10 (22%) of the 50 CRC. The findings showed that expression of c-Cbl and Cbl-b were associated with lymph vascular invasion in different ways (P<0.003, P<0.07). The LVI+ group had an expression that was up-regulated in comparison to the LVI- group (2.2% vs. 1.4%, 2.5% vs. 2.1%). In another study, it was found that c-Cbl plays a role in regulating CRC tumor growth through its interaction with β-catenin, regardless of CTNNB1 or APC mutation status. This study indicates a previously unrecognized activity of c-Cbl as a negative regulator of CRC [23]. Also, our findings showed that, in contrast to IBD and polyp groups, the expression level of c-Cbl was more highly regulated in CRC patients with a history of colitis. Moreover, compared to the IBD and colitis groups, the CRC patient with a history of polyp had a higher expression level of Cbl-b (P<0.001). There is proof that the oncogene's regulatory function is connected to cancer, which drives tumor growth. This study demonstrates a strong link between c-Cbl and the overall survival of patients with CRC and provides new insights into a possible role of the expression level of Cbl-b was variously associated with the CRC patient and there is evidence that the regulatory role of an oncogene is linked to cancer which acts as tumor progression. This study had some limitations including small sample size, and we examined analysis at an mRNA level; it would be better to verify our results by evaluating the findings in larger numbers.

Author Contributions

All the authors of this manuscript participated in all stages of the project, including research design, execution of lab experiments, data collection and analysis, and manuscript writing.

Funding Statement

This work was financially supported by Deputy of Research, Iran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.22407).

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Iran University of Medical Sciences. This study was compiled and approved by the ethics committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences in compliance with the requirements (Code No: IR.IUMS.REC.1400.1119), and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before participating in the study.

Consent to participate

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Consent to publish

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Data availability statement

Data will be available reasonable request.

References

2. Mozooni Z, Bahadorizadeh L, Yarmohammadi R, Jabalameli M, Amiri BS. The Role of Interferon-gamma and Its Receptors in Gastrointestinal Cancers. Pathology-Research and Practice. 2023 Jun 21:154636.

3. Simon K. Colorectal cancer development and advances in screening. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2016 Jul 19:967-76.

4. Hossain MS, Karuniawati H, Jairoun AA, Urbi Z, Ooi DJ, John A, et al. Colorectal cancer: a review of carcinogenesis, global epidemiology, current challenges, risk factors, preventive and treatment strategies. Cancers. 2022 Mar 29;14(7):1732.

5. Keum N, Giovannucci E. Global burden of colorectal cancer: emerging trends, risk factors and prevention strategies. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019 Dec;16(12):713-32.

6. Markman JL, Shiao SL. Impact of the immune system and immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2015 Apr;6(2):208-23.

7. Das V, Kalita J, Pal M. Predictive and prognostic biomarkers in colorectal cancer: A systematic review of recent advances and challenges. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017 Mar 1;87:8-19.

8. Fuccio L, Spada C, Frazzoni L, Paggi S, Vitale G, Laterza L, et al. Higher adenoma recurrence rate after left-versus right-sided colectomy for colon cancer. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2015 Aug 1;82(2):337-43.

9. Preisler L, Habib A, Shapira G, Kuznitsov-Yanovsky L, Mayshar Y, Carmel-Gross I, et al. Heterozygous APC germline mutations impart predisposition to colorectal cancer. Scientific Reports. 2021 Mar 4;11(1):5113.

10. Tang R, Langdon WY, Zhang J. Negative regulation of receptor tyrosine kinases by ubiquitination: Key roles of the Cbl family of E3 ubiquitin ligases. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2022 Jul 28;13:971162.

11. Onfroy-Roy L, Hamel D, Malaquin L, Ferrand A. Colon fibroblasts and inflammation: sparring partners in colorectal cancer initiation?. Cancers. 2021 Apr 7;13(8):1749.

12. Chen X, Jiang L, Zhou Z, Yang B, He Q, Zhu C, et al. The Role of Membrane-Associated E3 Ubiquitin Ligases in Cancer. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022 Jul 1;13:928794.

13. Stintzing S, Zhang W, Heinemann V, Neureiter D, Kemmerling R, Kirchner T, et al. Polymorphisms in genes involved in EGFR turnover are predictive for cetuximab efficacy in colorectal cancer. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics. 2015 Oct 1;14(10):2374-81.

14. Jun H, Jang E, Kim H, Yeo M, Park SG, Lee J, et al. TRAIL & EGFR affibody dual-display on a protein nanoparticle synergistically suppresses tumor growth. Journal of Controlled Release. 2022 Sep 1;349:367-78.

15. Pan X, Li C, Feng J. The role of LncRNAs in tumor immunotherapy. Cancer Cell International. 2023 Feb 21;23(1):30.

16. Li H, Zhang J, Ke JR, Yu Z, Shi R, Gao SS, Li JF, Gao ZX, Ke CS, Han HX, Xu J. Pro-prion, as a membrane adaptor protein for E3 ligase c-Cbl, facilitates the ubiquitination of IGF-1R, promoting melanoma metastasis. Cell Reports. 2022 Dec 20;41(12):111834.

17. Doghish AS, Elballal MS, Elazazy O, Elesawy AE, Elrebehy MA, Shahin RK, et al. The role of miRNAs in liver diseases: Potential therapeutic and clinical applications. Pathology-Research and Practice. 2023 Feb 14:154375.

18. Lotfollahzadeh S, Lo D, York EA, Napoleon MA, Yin W, Elzinad N, et al. Pharmacologic Manipulation of Late SV40 Factor Suppresses Wnt Signaling and Inhibits Growth of Allogeneic and Syngeneic Colon Cancer Xenografts. The American Journal of Pathology. 2022 Aug 1;192(8):1167-85.

19. Asbagh LA, Vazquez I, Vecchione L, Budinska E, De Vriendt V, Baietti MF, et al. The tyrosine phosphatase PTPRO sensitizes colon cancer cells to anti-EGFR therapy through activation of SRC-mediated EGFR signaling. Oncotarget. 2014 Oct;5(20):10070-83.

20. Richards S, Walker J, Nakanishi M, Belghasem M, Lyle C, Arinze N, et al. Haploinsufficiency of Casitas B-Lineage Lymphoma Augments the Progression of Colon Cancer in the Background of Adenomatous Polyposis Coli Inactivation. The American Journal of Pathology. 2020 Mar 1;190(3):602-13.

21. Kumaradevan S, Lee SY, Richards S, Lyle C, Zhao Q, Tapan U, et al. c-Cbl expression correlates with human colorectal cancer survival and its Wnt/β-catenin suppressor function is regulated by Tyr371 phosphorylation. The American Journal of Pathology. 2018 Aug 1;188(8):1921-33.

22. Cristóbal I, Manso R, Rincón R, Caramés C, Madoz-Gúrpide J, Rojo F, et al. Up-regulation of c-Cbl suggests its potential role as oncogene in primary colorectal cancer. International journal of Colorectal Disease. 2014 May;29:641.

23. Shashar M, Siwak J, Tapan U, Lee SY, Meyer RD, Parrack P, et al. c-Cbl mediates the degradation of tumorigenic nuclear β-catenin contributing to the heterogeneity in Wnt activity in colorectal tumors. Oncotarget. 2016 Nov 11;7(44):71136-50.