Abstract

Cancer is one of the most dreaded diagnosis, with significant impact on the patient, carer and family. The diagnosis can lead to variety of emotions like confusion, anger, despair and fear. In case of Indigenous peoples, the process of sickness, disease and treatment are all closely related to connection to land, country, family and community. This paper evaluates the different responses recorded as a part of a larger Indigenous Australian study, regarding the feelings and emotions one feels when they hear of cancer (“the Big C”) in the community or family. The evaluation follows a brief discussion on the evidence available regarding the emotions recorded and the relevance in Indigenous peoples and circumstances. A deeper understanding of the impact of cancer in the community will also be beneficial, in providing informal carers or family members with the appropriate support they need to concur their own stress and anxiety.

Introduction

Emotions significantly effect psychological well-being and have a substantial impact on health [1]. The dynamic nature of the relationship between these factors is articulated by the World Health Organization: “Normally, emotions such as anxiety, anger, pain or joy interact to motivate a person to a goal-directed action. However, when certain emotions predominate and persist beyond their usefulness in motivating people for their goal-directed behaviour, they become morbid or pathological” [2]. Thus, it is crucial to consider the emotional state of cancer patients and carers and routinely monitor emotional wellbeing, similar to indicators of physical health such as blood pressure, pulse rate, and temperature [1]. The diagnosis of cancer is particularly difficult to navigate for carers, as treatment and support is typically limited to the cancer patient. Lack of available or adequate support can result in emotionally distressing circumstances for both families and communities.

Indigenous communities around the world have exhibited immense strength and resilience in the face of devastating impacts of colonisation, assimilation and attempted elimination of their cultures and peoples [3]. Despite this fortitude, the effect of colonisation and various government policies has resulted in irreversible damage to Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing. The continuing influence of systemic racial discrimination and global capitalism is further attributing to the health inequities faced by Indigenous peoples [4,5]. While there has been an observed reduction in chronic disease mortality rates among Indigenous populations, rates of cancer and associated mortality have intensified [6-9]. Cancer is the second most common cause of death among Indigenous peoples in Australia, and cancer survival rates are significantly lower among Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous Australians [10]. The increased global burden of cancer among Indigenous populations has led to an amplified research interest [9,11].

Connection to country is a vital spiritual connection for Indigenous peoples as it defines ancestral relationships and contributes towards culture and sovereignty [12]. The connection to land and Country is continued by keeping and passing of knowledge and responsibilities. Identity, kinship, culture, health, wellness and family are also deeply embedded in this connection [13-15]. Recognising these is a key pillar of the Well-being framework for Aboriginal people with chronic illness [16] and Optimal Care Pathways for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer in Australia [17]. The support of family and community play an indispensable role in alleviating cancer outcomes and survivorship, which can be achieved by acknowledging and respecting the family structures and values of Indigenous cultures. Most health care systems fail to recognise and acknowledge this connection in addition to the significant role of family and community [18-20]. It has been reported that cultural respect is a key factor which helps to achieve active engagement and interest by Indigenous patients [21-23]. For Indigenous peoples the experience of care is more elaborate as the health of an individual is determined by the emotional, cultural, social and physical well-being of an entire community [24]. This is mirrored in Australia’s National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework, which specifies that optimal cancer care should be “person centred so that the whole person (including family and cultural role) is considered, and the psychosocial, cultural and supportive care needs and preferences of Indigenous people are addressed across the continuum of care” [25]. Indigenous communities have suggested that individual life circumstances and personal experiences are relevant [26]. Acceptance by healthcare workers about broader cultural issues and the avoidance of generalisation of all Indigenous patients could play a pivotal role in increasing engagement of families in the cancer process [26]. A study from New Zealand [27] describes the cultural expectations and sensitivity anticipated from healthcare workers by Maori (Indigenous population of New Zealand) cancer patients, where the importance of having tikanga (customs and values) processes at the hospitals is emphasized. A Maori participant in the study elaborates:

“. . . the whole tikanga within the process. Knowing that we come with many wh?nau members, children, aunties, uncles, everybody wants to come, so shared rooms don't really meet our needs. Having somewhere for our children, so that they’re not being a distraction or a h?h? [nuisance], but that they need to be there and their koro’s [grandfathers], their nans, they need them there. … This is part of your healing process, this is what is going to make it better for you. ‘Cause in here it’s a positive outlook for them and that will improve their treatment response [27].”

It has been reported that family plays a critical role during treatment and impacts survivorship; additionally, patient and health of other family members take priority over the caregiver’s own health [24,28]. Risetevski and colleagues found that families often felt they did not receive supportive care and did not feel welcome in hospitals [28]. The National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework [24] emphasizes the need for families and carers to be “involved, informed, supported and enabled throughout the cancer experience” [24].

Cancer requires long term support and intervention strategies, the burden of which usually falls on informal caregivers (family). Research among cancer survivors has revealed that health behaviours and coping are interrelated, with significant implications for positive behaviour alterations and improved health [29,30]. It has been previously discussed that poor health behaviours for example stress and anxiety of informal caregivers impact the health of survivors [31-34]. The fear and confusion associated with cancer demonstrates the necessity of exploring the emotional responses of Indigenous peoples on hearing Cancer in the community to improve understanding and increase support. This paper explores these emotional responses and provides an insight to understanding the perception of the impact of cancer for Indigenous Communities.

Findings from HPV-OPC Study

Methodology

The data used to explore the impact of cancer diagnoses for Indigenous communities is from the HPV-OPC Human Papillomavirus and Oropharyngeal Carcinoma (HPV-OPC) project which is a prospective longitudinal cohort study based in South Australia [35]. Participant eligibility was self-identification of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status, aged 18+ years and a South Australian resident. Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations (ACCHOs) were key stakeholders and heavily involved in participant recruitment at baseline. An Indigenous Reference Group was established to ensure Indigenous governance of all aspects of the project. The reference group was chaired by an Indigenous health manager and included Indigenous community members, health workers and councillors.

Baseline data was collected from February 2018 to January 2019 with 12-month follow-up data collected from February 2019 to January 2020. Information on socio-demographic factors, sexual behaviours and health-related behaviours were ascertained by self-report questionnaire, with assistance provided by the study’s Senior Indigenous Research Officer (JH) where required. All components of data collection were pilot tested and tailored for cultural sensitivity.

Ethical approval was received from the University of Adelaide Human Research Ethics Committee and the Aboriginal Health Council of South Australia’s Human Research Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

Sociodemographic characteristics

Age (dichotomised based on median split at 37 years; 37 and less or 38 and more), sex (male or female), geographic location (metropolitan, i.e. residing in Adelaide, South Australia’s capital city and non-metropolitan; i.e. residing elsewhere in the state) and level of education attained (till high school and above high school including trade, TAFE which stands for technical and further education and provides training for vocational occupations, or university).

Emotional response to cancer in family or community

Individual responses (Yes/No) to the question regarding the response to cancer in the community or family (Table 1) was explored. The objective was to gain better understanding of the approaches to consider for management of cancer in the Indigenous community, driven by the Aboriginal community. Apart from the list of emotions provided, there was an option to specify any other emotions identified. Data was descriptively analysed using SPSS (IBM; Version 27).

|

WHEN OTHERS IN YOUR FAMILY/COMMUNITY GET CANCER/ THE BIG C, DO YOU FEEL? |

||

|

ANGER |

Yes |

No |

|

FRUSTRATION |

Yes |

No |

|

SADNESS |

Yes |

No |

|

GUILT |

Yes |

No |

|

REVENGE |

Yes |

No |

|

FEAR |

Yes |

No |

Results

1011 participants were recruited at baseline (February 2018 to January 2019), across eight sites in South Australia. This cohort represents 5% of Indigenous adults in South Australia eligible for recruitment in this study.

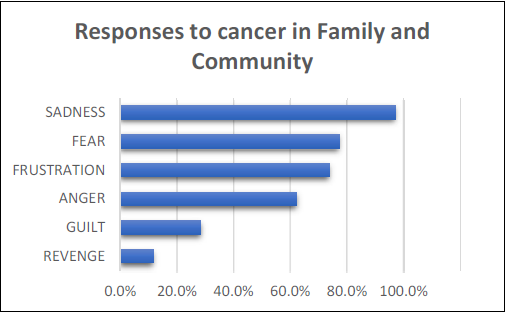

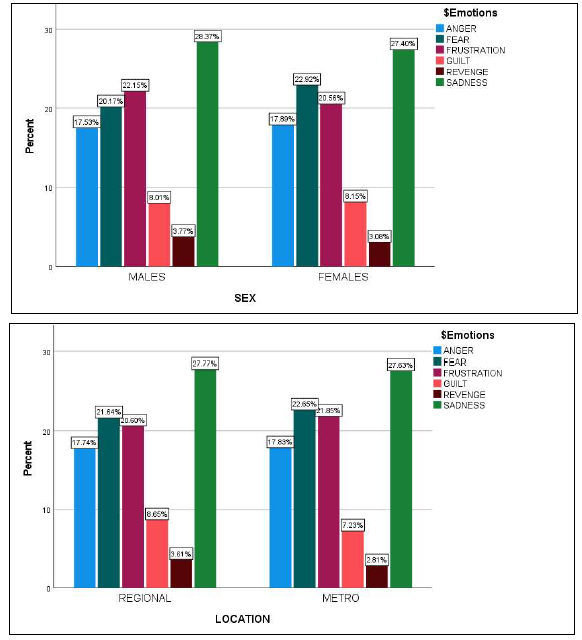

Of the 1011 participants, 998 responded to the question about how they felt about cancer in the family/community. Of the 988 participants more than half (66.6%) were females, and almost half (49.5%) were below the age of 37 years. Almost two-thirds (62.6%) resided in non-metropolitan locations and 67.5% reported high school as the highest educational attainment. More than half reported to feeling Anger (58.2%) and 69% reported feelings of frustration. Most (90.8%) reported feeling sad, 26.6% felt guilt whilst 10.8% reported feelings of revenge on hearing of cancer in the family or community. Almost three-quarters (72.1%) reported feeling fear on hearing the diagnosis (Figures 1 and 2, Table 2).

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the most frequently recorded responses.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of gender and location specific responses to cancer in the family/community.

|

|

Responses |

|

|

N |

Percent |

|

|

Anger |

581 |

62.3% |

|

Frustration |

689 |

73.9% |

|

Sadness |

906 |

97.2% |

|

Guilt |

265 |

28.4% |

|

Revenge |

108 |

11.6% |

|

Fear |

720 |

77.3% |

|

Characteristic

|

HPV-OPC study emotional response recoded (%, 95%CI) |

|||||

|

|

Anger (N=581) |

Frustration (N=689) |

Sadness (N=906) |

Guilt (N=265) |

Revenge (N=108) |

Fear (N=720) |

|

Total (100) |

58.2 (55.1-61.2) |

69.0 (66.1-71.8) |

90.8 (88.9-92.5) |

26.6 (23.9-29.4) |

10.8 (9.0-12.9) |

72.1 (69.3-74.9) |

|

Sex Male Female |

32.0 (28.3-35.9) 68.0 (64.1-71.7) |

34.1 (30.6-37.7) 65.9 (62.3-69.4) |

33.2 (30.2-36.3) 66.8 (63.7-69.8) |

32.1 (26.7-37.9) 67.9 (62.1-73.3) |

37.0 (28.4-46.4) 63.0 (53.6-71.6) |

29.7 (26.5-33.1) 70.3 (66.9-73.5) |

|

Age >37 <37 |

49.1 (45.0-53.1) 50.9 (46.9-55.0) |

50.2 (46.5-53.9) 49.8 (46.1-53.5) |

49.7 (46.4-52.9) 50.3 (47.1-53.6) |

46.4 (40.5-52.4) 53.6 (47.6-59.5) |

39.8 (31.0-49.2) 60.2 (50.8-69.0) |

51.7 (48.0-55.3) 48.3 (44.7-52.0) |

|

Geographic Location Regional Metropolitan |

61.8 (57.8-65.7) 38.2 (34.3-42.2) |

60.5 (56.8-64.1) 39.5 (35.9-43.2) |

62.0 (58.8-65.1) 38.0 (34.9-41.2) |

66.0 (60.2-71.5) 34.0 (28.5-39.8) |

67.6 (58.4-75.9) 32.4 (24.1-41.6) |

60.8 (57.2-64.3) 39.2 (35.7-42.8) |

|

Level of Education Till High school TAFE/University |

67.6 (63.8-71.4) 32.4 (28.6-36.2) |

67.5 (63.9-70.9) 32.5 (29.1-36.1) |

68.2 (65.1-71.2) 31.8 (28.8-34.9) |

67.5 (61.7-73.0) 32.5 (27.0-38.3) |

72.2 (63.3-80.0) 27.8 (20.0-36.7) |

67.5 (64.0-70.8) 32.5 (29.2-36.0) |

|

**HPV-OPC: Human Papillomavirus - Oropharyngeal Carcinoma study; CI: Confidence Intervals; TAFE: Provides training for technical education |

||||||

Discussion

Cancer has substantial repercussions on an individual and their families [36,37]. It has been reported that significant emotional, social, physical and, spiritual changes occur in a family after a family member has been diagnosed with cancer [38]. Green et al. [26] described the context of cancer as described by Indigenous participants. The most important factors identified were the experiences of racism (past and present), discrimination, Indigenous health disparities, mistrust in the healthcare system and different lifestyles. There was an unacceptable notion of generalizing all Indigenous peoples’ life, culture and, circumstances [26].

The emotional cycle of cancer can be broadly divided into 3 stages; stage of diagnosis, stage of treatment and stage of recurrence. The stage of diagnosis and recurrence is most frequently associated with fear and sadness. Gorman and colleagues [36] explain the family’s fears associated with cancer and elaborated on it in reference to the stage of diagnosis and recurrence. They indicated that fear can be multifactorial including a loss of their relationship, the loss of control, the fear of sorrow and, the fear of pain and suffering.

The following section discusses each emotion (Fear, Anger, Frustration, Guilt, Sadness and, Revenge) individually. The association of these emotions with cancer in the community or family, with any prior research in regards to Indigenous communities, is discussed.

Fear

The Recognition Phase of cancer [39], includes the individual’s awareness about changes in their body which could indicate cancer, including abnormal growth, pain, or bleeding. Fear of cancer or previous cancer in the family/community can lead to a delay in acknowledging the changes and demotivate the patient to seek a diagnosis. This fear could be due to financial limitations, fear of healthcare providers, fear of dependency, or fear of disfigurement [36]. The roots of this fear are reinforced by avoidance of using the word – CANCER [40,41]. The fear of seeing a loved one in a vulnerable state has been associated with distress, fearing a change in personality and the dynamics of their relations [36]. Partners and spouses feel overwhelmed as they have not reflected what life together with illness and suffering would involve [42]. A cancer diagnosis can either distance couples due to the stress on the relationship or can bring them closer together as a part of the survival struggle [37]. Many Indigenous languages do not define the word “cancer” and are frequently associated with bad spirits and negative energies [43]. This adverse energy creates a fearful aura which is further fed into, by the scarce involvement of Indigenous peoples in health promotional activities and media awareness presentations [44]. Green et al. recorded the lack of open discussions about the ‘C-Word’ in Indigenous communities, which was associated with stigma and the large amount of stress [26]. Cancer is often associated with feelings of shame which leads to a late diagnosis and a poorer prognosis [43]. This highlights a large gap in communication about cancer and its management amongst Indigenous populations. The impact of institutional racism and intimidation of Indigenous patients due to ‘cold’ interactions with ‘medical monsters’ or the ‘dominant white medical culture’ further impedes successful engagement and instils fear [26]. The impact of racism was voiced by a study by the Maori [27];

“Our koros and our kuias [elders]; their mana [status/authority] gets tramped on. Their wishes don’t get respected. If you are t?turu to your M?ori-ness [everything is subsumed by your M?ori identity], you know that the wh?nau looks after their own. And when they are sick and they go to the hospital, that all goes out the window. It becomes, excuse me, the white man’s rule. There is no negotiating. You do it this way or you get out. I don’t get out. I got a mouth. And our old people, they don’t want other people wiping their bums, washing them. That is what keeps their mana intact, having that respect. . .. Their [HCP] job is to look after the tinana [body], but you need to look after the wairua [spirit/soul] too. Because that’s what keeps the person going.”

Anger and Frustration

An initial period of ambiguity and doubt is frequently followed by extreme reactions of anger and frustration, eventually leading to psychological distress and disruption. The family/community may go through denial or they may blame others for this diagnosis [36]. They may experience vulnerability with the conscious thought that this could happen to them. The inability of an individual to help or protect a loved one can create intense vulnerability, helplessness and, frustration [36]. Green et al. [26] reported that health professionals do recognize the fear and anger amongst Indigenous patients and felt that one bad experience could be critical in defining the care journey for the entire family/community. The emotional frustration and anger can be inferenced from quotes of participants in various studies [26,27];

“‘And they said, “Oh, Aboriginal people don’t burn when they have radiation”. And that’s an outright lie …Because I was burnt red raw from radiation [26].”

“We sat there absolutely petrified, waiting to squeeze every little bit of information they had in that little half an hour session. A secretary from upstairs came down twice to present some other patient’s case. And it just broke… I was just angry after that. …I thought we were going to get their devoted attention [27].”

Other factors which precipitate feelings of frustration include disorder in daily chores such as sustaining a job, taking care of dependents and, other domestic errands [36]. A loss of control surrounds the patient and the family, as they come to terms with the realization that there is nothing that they can do to stop the disease. This can spawn many emotions, with anger being the most common. This anger is often expressed to healthcare workers (physicians and nurses) for their incapability and inefficiencies [36]. The loss of control and its associated anger also arises from other areas of patients’ lives including loss of sleep, anxiety, conflicts within the family and disordered schedules.

Guilt

The most feared aspect of cancer for the patient and family is metastasis and recurrence. This is associated with depression, guilt, fear of death and anger. It has been observed that patients with recurrences lean towards less contact with family and loved ones due to the feelings of extensive strain on relationships and overwhelming changes in the emotional climate [45,46]. The patient feels constantly guilty of the emotional, physical, social and financial drain caused to the family by their illness. Conversely, it has been observed that positive support from partners or families may result in heightened confidence among patients to fight the illness and relationships are stronger to face any new challenges. Thus, the perception and management of cancer in the family /community is a very important aspect, which controls the psychological balance of the patient [36]. Guilt may be a cardinal feature of the caregiving experience, and to fully understand the implications of this complex phenomenon, more research is recommended.

Sadness

There is a constant surge in the apprehensions regarding the loss of life which produce strong emotions, which all lead to intense sadness. The grieving process initiates with denial leading to anger, irritability and despair ending in sadness. It has been observed that the intensity of sadness increases if the family members protect themselves by avoidance or preoccupation [36]. Acceptance and supporting the loved ones, regardless of age, is extremely important in this process [47]. From an Indigenous perspective, it has been found that being away from one’s own Country or traditional lands, as well as the likelihood of dying off Country, was a particular cause of sadness [26]. Green et al. found that all Indigenous participants reported intense grief and shock when they heard of cancer in their family or community [26].

Revenge

Studies have reported the correlational and causal role of anger in precipitating feelings of revenge [48-50]. Anger is the most significant predictor of vengeance [51]. In case of perceived injustices, there is a sense of morally appropriate anger that triggers feelings of revenge [52]. Although there is limited literature which records the emotional feelings of revenge amongst community members or family members of cancer patients, it emerges as a possible consequence. This consequence can be explained by the feelings of intense anger and frustration felt by families which could promote feelings of revenge or vengeance as well.

Some useful interventions include assisting family/community in facing their loss, recognizing their struggles to support the patient, and ascertaining ways to affirm patients and families sense of control [36]. It has been reported that family caregivers had improved mourning outcomes when they felt they had accomplished something to cherish such as providing comfort and compassion to their loved one [53]. Australia’s National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework emphasizes the assessment of Indigenous understandings of care, to augment the capacity of cancer services [24]. Community suggested solutions included more open conversations or yarns (‘Yarning’ is a popular term used for an Indigenous style of conversation and storytelling) [54] about the cancer journey and available resources and pathways [26]. The appointment of Indigenous liaison officers or health workers was emphasized in one study [26] and suggested that it would enable the family to trust the system, voice their concerns and further facilitate relationships with the healthcare workforce.

There is an increase in the level of acknowledgment that diverse methods are required to effectively capture and appreciate the perspectives and perceptions of cancer among Indigenous communities [55-57]. Despite the increase in awareness, there is limited pragmatic evidence regarding the best methodology to achieve desirable results. In general, measurement of Indigenous cancer patients’ experiences is a complex process, and the additional aspects such as poor cancer outcome increase the challenge and urgency of the situation.

References

2. WHO. 2006.

3. Conte KP, Gwynn J, Turner N, Koller C, Gillham KE. Making space for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community health workers in health promotion. Health Promot Int. 2020;35(3):562-74.

4. Taylor EV, Lyford M, Parsons L, Mason T, Sabesan S, Thompson SC. “We’re very much part of the team here”: A culture of respect for Indigenous health workforce transforms Indigenous health care. PLOS One. 2020;15(9):e0239207.

5. Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet (London, England). 2009;374(9683):65-75.

6. Cabinet. DotPMa. Closing the Gap Prime Minister's report 2020. 2020.

7. McLennan WMR. The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics. 1997.

8. Vos T, Barker B, Begg S, Stanley L, Lopez AD. Burden of disease and injury in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: the Indigenous health gap. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;38(2):470-7.

9. Condon JR, Zhang X, Baade P, Griffiths K, Cunningham J, Roder DM, et al. Cancer survival for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: a national study of survival rates and excess mortality. Population Health Metrics. 2014;12(1):1.

10. Australia. AIoHaWC. Cancer in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia: an overview. Cancer Series no78. 2013.;Cat. no. CAN 75.

11. Sarfati D, Garvey G, Robson B, Moore S, Cunningham R, Withrow D, et al. Measuring cancer in indigenous populations. Annals of Epidemiology. 2018;28(5):335-42.

12. Kingsley J, Townsend M, Henderson-Wilson C, Bolam B. Developing an exploratory framework linking Australian Aboriginal peoples' connection to country and concepts of wellbeing. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2013;10(2):678-98.

13. Meiklejohn JA, Bailie R, Adams J, Garvey G, Bernardes CM, Williamson D, et al. “I’m a Survivor”: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Survivors’ Perspectives of Cancer Survivorship. Cancer Nursing. 2020;43(2).

14. Shahid S, Durey A, Bessarab D, Aoun SM, Thompson SC. Identifying barriers and improving communication between cancer service providers and Aboriginal patients and their families: the perspective of service providers. BMC Health Services Research. 2013;13(1):460.

15. Shahid S, Finn LD, Thompson SC. Barriers to participation of Aboriginal people in cancer care: communication in the hospital setting. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2009;190(10):574-9.

16. Davy C, Kite E, Sivak L, Brown A, Ahmat T, Brahim G, et al. Towards the development of a wellbeing model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with chronic disease. BMC Health Services Research. 2017;17(1):659.

17. Chynoweth J, McCambridge MM, Zorbas HM, Elston JK, Thomas RJS, Glasson WJH, et al. Optimal Cancer Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: A Shared Approach to System Level Change. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;6:108-14.

18. Aspin C, Brown N, Jowsey T, Yen L, Leeder S. Strategic approaches to enhanced health service delivery for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with chronic illness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:143.

19. Tam L, Garvey G, Meiklejohn J, Martin J, Adams J, Walpole E, et al. Exploring Positive Survivorship Experiences of Indigenous Australian Cancer Patients. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(1):135.

20. Cavanagh BM, Wakefield CE, McLoone JK, Garvey G, Cohn RJ. Cancer survivorship services for indigenous peoples: where we stand, where to improve? A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice. 2016;10(2):330-41.

21. Wotherspoon C, Williams CM. Exploring the experiences of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients admitted to a metropolitan health service. Australian health review : a publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2019;43(2):217-23.

22. Shahid S, Finn L, Bessarab D, Thompson SC. 'Nowhere to room … nobody told them': logistical and cultural impediments to Aboriginal peoples' participation in cancer treatment. Australian Health Review : a Publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2011;35(2):235-41.

23. Tranberg R, Alexander S, Hatcher D, Mackey S, Shahid S, Holden L, et al. Factors influencing cancer treatment decision-making by indigenous peoples: a systematic review. Psycho-Oncology. 2016;25(2):131-41.

24. Australia C. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework. Surry Hills, NSW, Australia. 2015.

25. Australia. C. National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Cancer Framework 2015. Cancer Australia, Surry Hills, NSW Accessed 6 Dec 2018.

26. Green M, Anderson K, Griffiths K, Garvey G, Cunningham J. Understanding Indigenous Australians’ experiences of cancer care: stakeholders’ views on what to measure and how to measure it. BMC Health Services Research. 2018;18(1):982.

27. Kidd J, Cassim S, Rolleston A, Chepulis L, Hokowhitu B, Keenan R, et al. Hā Ora: secondary care barriers and enablers to early diagnosis of lung cancer for Māori communities. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):121.

28. Risetevski E TS, Kingaby S, Nightingale C and Iddawela M. Understanding Aboriginal Peoples’ Cultural and Family Connections Can Help Inform the Development of Culturally Appropriate Cancer Survivorship Models of Care. JCO Global Oncology. 2020;6:124-32.

29. Litzelman K, Kent EE, Rowland JH. Interrelationships Between Health Behaviors and Coping Strategies Among Informal Caregivers of Cancer Survivors. Health Education & Behavior : the Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education. 2018;45(1):90-100.

30. Park CL, Iacocca MO. A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping. 2014;27(2):123-37.

31. Daly J, Sindone AP, Thompson DR, Hancock K, Chang E, Davidson P. Barriers to participation in and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation programs: a critical literature review. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing. 2002;17(1):8-17.

32. James EL, Stacey F, Chapman K, Lubans DR, Asprey G, Sundquist K, et al. Exercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health (ENRICH): the protocol for a randomized efficacy trial of a nutrition and physical activity program for adult cancer survivors and carers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:236.

33. Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association. 2004;23(6):599-611.

34. Weaver KE, Rowland JH, Augustson E, Atienza AA. Smoking concordance in lung and colorectal cancer patient-caregiver dyads and quality of life. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention : A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2011;20(2):239-48.

35. Jamieson LM, Garvey G, Hedges J, Leane C, Hill I, Brown A, et al. Cohort profile: indigenous human papillomavirus and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma study - a prospective longitudinal cohort. BMJ Open. 2021;11(6):e046928.

36. Gorman LM. Psychosocial Impact of Cancer on the Individual, Family, and Society. Psychosocial Nursing Care Along the Cancer Continuum. 2018(3):1-21.

37. Glajchen M. The emerging role and needs of family caregivers in cancer care. The Journal of Supportive Oncology. 2004;2(2):145-55.

38. Northouse L. Helping families of patients with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2005;32(4):743-50.

39. Nail LM. I'm coping as fast as I can: psychosocial adjustment to cancer and cancer treatment. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28(6):967-70.

40. Holland JC. History of psycho-oncology: overcoming attitudinal and conceptual barriers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64(2):206-21.

41. Holland JC. American Cancer Society Award lecture. Psychological care of patients: psycho-oncology's contribution. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2003;21(23 Suppl):253s-65s.

42. Shell JA, & Kirsch, S. ). . Psychosocial issues, outcomes, and quality of life. Oncology Nursing. 2001;4: 948-72.

43. J P. There’s no aboriginal word for cancer. Origins. 2013;1 22 - 3.

44. Treloar C, Gray R, Brener L, Jackson C, Saunders V, Johnson P, et al. Health literacy in relation to cancer: addressing the silence about and absence of cancer discussion among Aboriginal people, communities and health services. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2013;21(6):655-64.

45. Mahon SM, Casperson DS. Psychosocial concerns associated with recurrent cancer. Cancer Practice. 1995;3(6):372-80.

46. R DBaS. Supporting families in Palliative Care. supporting Families in Palliative care - Social Aspects of Care.

47. Hames CC. Helping Infants and Toddlers When a Family Member Dies. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2003;5(2).

48. Barber L, Maltby J, Macaskill A. Angry memories and thoughts of revenge: The relationship between forgiveness and anger rumination. Personality and Individual Differences. 2005;39:253-62.

49. Eisenberger R, Lynch P, Aselage J, Rohdieck S. Who takes the most revenge? Individual differences in negative reciprocity norm endorsement. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin. 2004;30(6):787-99.

50. Lerner J, Goldberg J, Tetlock P. Sober Second Thought: The Effects of Accountability, Anger, and Authoritarianism on Attributions of Responsibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1998;24:563-74.

51. Roseman IJ, Wiest C, Swartz TS. Phenomenology, behaviors, and goals differentiate discrete emotions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;67(2):206-21.

52. Tripp TM BR. “Righteous” anger and revenge in the workplace: the fantasies, the feuds, the forgiveness. International Handbook of Ange. 2010;ed. M Potegal, G Stemmer, C Spielberger:pp. 413-31.

53. Koop PM, Strang VR. The bereavement experience following home-based family caregiving for persons with advanced cancer. Clinical Nursing Research. 2003;12(2):127-44.

54. Laycock A wWD, Harrison N, Brands J. Researching Indigenous health: a practical guide for researchers. . The Lowitja Institute, Melbourne. 2018.

55. Information. BoH. Patient perspectives – hospital care for Aboriginal people. Sydney (NSW). 2016.

56. Green M, Cunningham J, O'Connell D, Garvey G. Improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with cancer requires a systematic approach to understanding patients' experiences of care. Australian Health Review : A Publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2017;41(2):231-3.

57. Yerrell PH, Roder D, Cargo M, Reilly R, Banham D, Micklem JM, et al. Cancer Data and Aboriginal Disparities (CanDAD)-developing an Advanced Cancer Data System for Aboriginal people in South Australia: a mixed methods research protocol. BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e012505-e.