Abstract

The hallmark of neoplastic transformation is a significant increase in master regulator complex network entropy of cancer cell. This happens as a result of breakdown of the fine interplay of the second law of thermodynamics with the living cell. The methodologies that have been employed towards elucidation of spatial genomics and polyomics of tumor mass, could be applied towards the generation of spatial master regulator complex network entropy, or spatial entropyomics of tumor mass. This would lead to the birth of a new blueprint for the development of future cancer therapeutics.

Introduction

Cancer and time have hand in hand [1], just like the passage of time along the thermodynamics arrow and aging. In case of aging of living cell, cellular network entropy increases smoothly for the most part [2]. In case of cancer, this increase happens at an aggressive, wild, and fast pace [3].

The control loops, such as apoptotic machinery [4], telomeres [5], and P53 [6], are mostly dysfunctional in cancer cell, and hence, not able to stop progression of neoplastic transformation. The evolution of cancer therapeutics in the last eighty years, from nitrogen mustard [7], to new generation of immunotherapy [8], and targeted therapeutic agents [9], and their limited success in metastatic neoplastic disorders, necessitates a new approach to this catastrophic disease.

Advancement of science including development of single cell sequencing [10] has made it possible to elucidate the evolutionary road map of tumor mass [11] along the axis of time. We have become able to identify genomics [12], epigenomics [13], micro-RNA diversity [14], and proteomics [15] of thousands of cells in neoplastic mass, as well as their dynamics of variation along the axis of time.

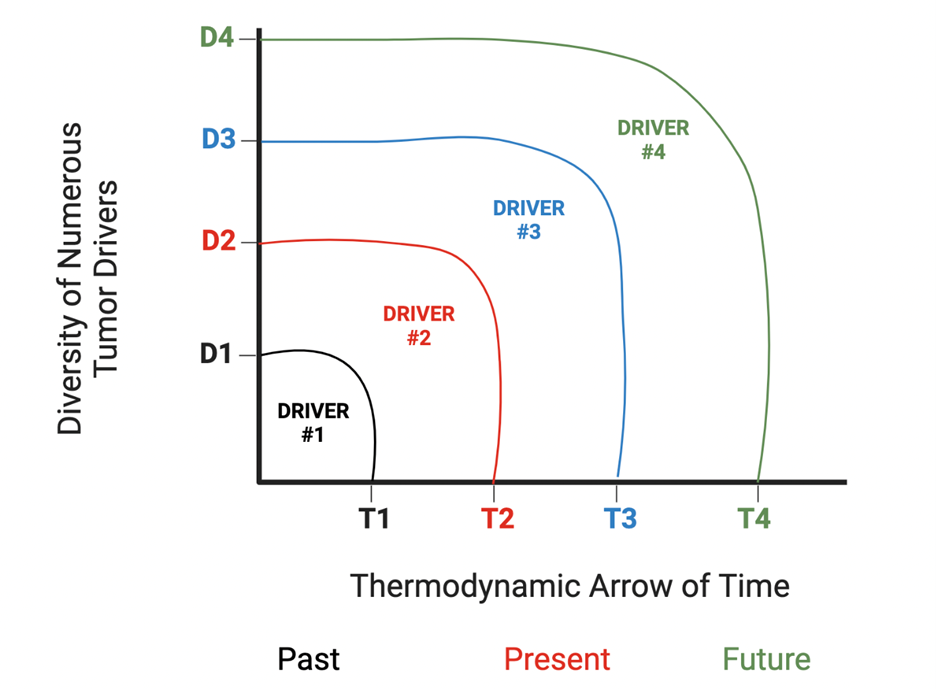

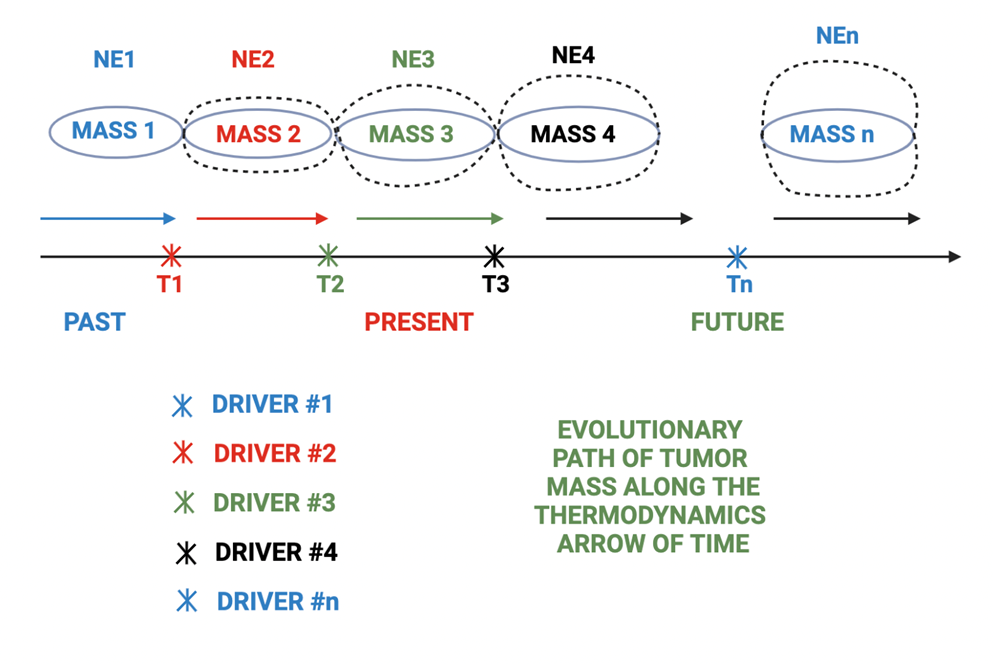

Based on available mathematical models [16] and published studies, we could measure master regulator complex network entropy of cells comprising the tumor mass [17] and develop models similar to spatial genomics, called spatial entropyomics. The main difference between spatial genomics and spatial entropyomics is that the latter lends itself to a much more practical and simpler therapeutic application. Here, we need to change one value, as compared with dealing with a complex genetic network. The simplicity and feasibility of this approach could potentially make it the main therapeutic strategy for neoplastic disorders in the future. One needs to keep in mind that the leading or driving zone of neoplastic mass, along the thermodynamic arrow of time [18], is the one with the highest cellular master regulator complex network entropy. As such, the driver zone is in constant flux and is persistently getting replaced with the one that has acquired a higher network entropy. (Figure 1). This value correlates with chromosomal or genetic instability (CIN) [19], which in turn shapes intra-tumor heterogeneity (ITH) (Figure 2) [20].

Figure 1. Different drivers come into existence to take over the forward evolutionary move of tumor mass, along the axis of time.

Figure 2. Cellular network entropy [NE] constantly increases, and the forward evolutionary move of tumor mass, along the thermodynamic arrow of time, is managed by new born drivers at more advanced stages of cancer evolution shown by bigger size. NE: Network Entropy; Mass: Tumor Mass.

Consequently, the current notion of one driver zone is wrong, and targeting that zone would further promote the birth of a new driver zone with a higher master regulator network entropy. Spatial entropyomics model is expected to allow us to calculate the value of a yet unborn future driver zone, master regulator complex network entropy. So, in our future cancer therapeutics design, not only would we shift the calculated driver front network entropy toward normalcy, but also preemptively do the same thing to the future and as yet unborn values.

Design of Programmable Nano-Machines [21]

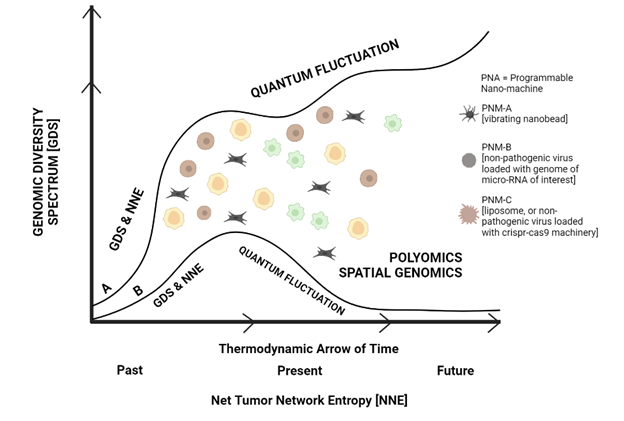

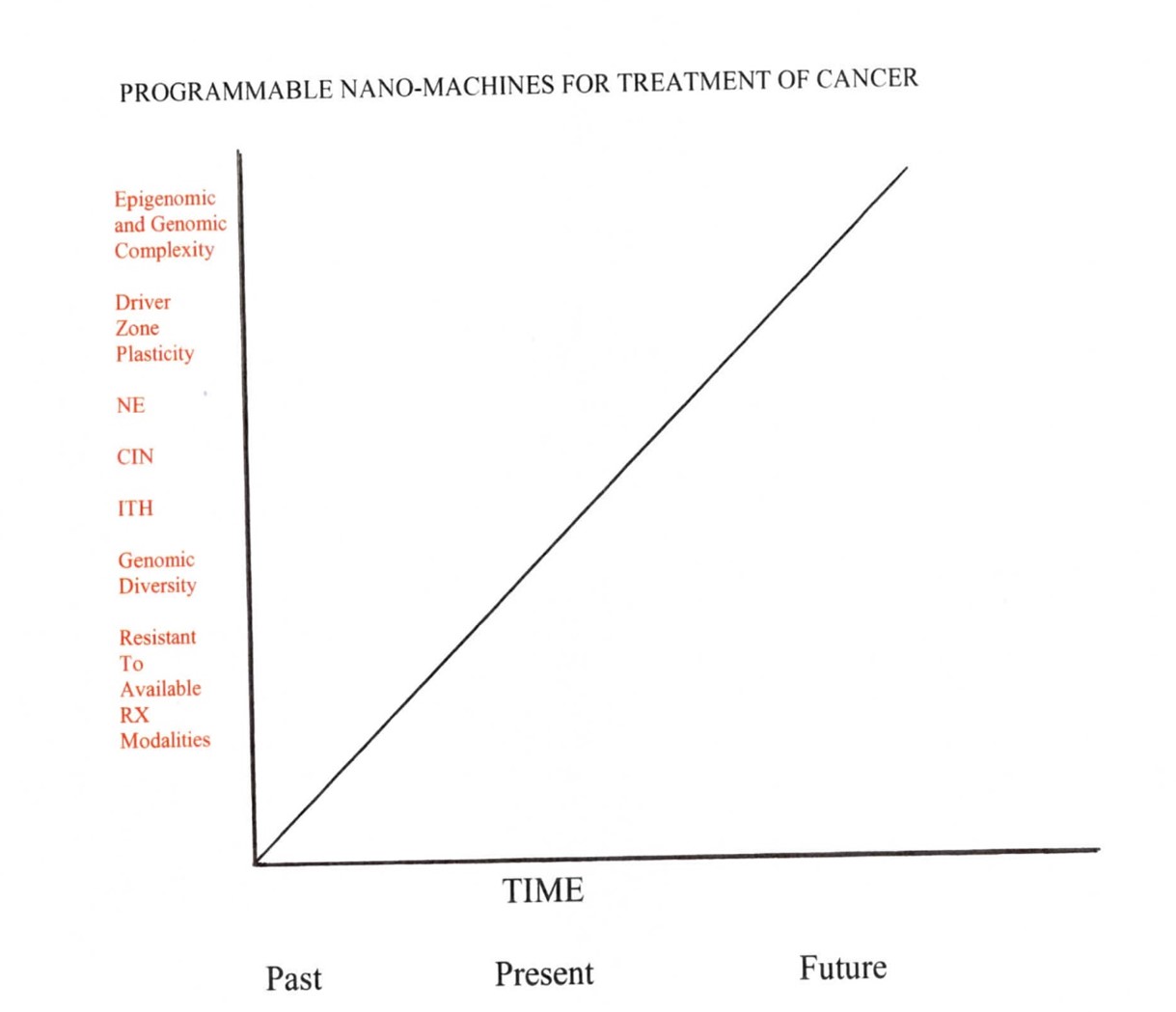

Cancer can be treated based on spatial entropyomics concept. Figures 3 and 4, depict the basic principles and concepts that govern homeostasis and evolution of tumor mass. These concepts and principles build the foundation on which the design of future cancer therapeutics by employing nano-machines. Figure 5 depicts conversion of curve A to curve B. Curve A, shows an increase in genomic diversity [22] and net tumor network entropy, along the axis of time. Curve B, shows a decrease in genomic diversity and net tumor network entropy through the therapeutic effect of programmable nano-machines.

Figure 3. The value of epigenomic and genomic complexity, as well as driver zone plasticity and its network entropy constantly increase along the thermodynamic arrow of time. These changes get reflected into a higher CIN, ITH and resistance to available treatment measures. CIN: Chromosomal Instability; ITH: Intratumor Heterogeneity.

Figure 4. Regulator of the driver zone is the most ideal target for programmable nano-machines. By using artificial intelligence [32] and machine learning technology [33], we could identify RDZ. This zone is expected to have the highest master regulator network entropy, which correlates with CIN and ITH, and inversely correlates with the transmembrane electrostatic force [33]. RDZ: Regulator of Driver Zone; CIN: Chromosomal Instability; ITH: Intratumor Heterogeneity.

Figure 5. Programmable nano-machines would convert curve A, a tumor with higher genomic diversity and net tumor network entropy, to curve B, a tumor with lower genomic diversity and net tumor network entropy.

Programmable nano-machines, could have one of the many possible designs, including vibrating nano-beads [23], non-pathogenic viruses [24], loaded with crispr-cas9 editing machinery [25], or micro-RNA of interest [26], all the way to smart molecules [27] capable of executing the task of interest.

The common denominator among a diverse group of programmable nano-machines, is their capability to decrease the leading or driving front network entropy as close to normal as possible. By doing so, the driver front loses its capability of evolutionary forward move of tumor mass into a higher level of genomic complexity, CIN, ITH, and cellular network entropy. Consequently, neoplastic disorder [28] loses its progression capability and it shifts toward a chronic disease [29]. Such treatment could get repeated at predetermined time intervals, calculated for migration of spatial entropyomics to a lower level of cellular master regulator complex network entropy.

Conclusion

Spatial entropyomics, is expected to give birth to a new blueprint and path to future cancer therapeutics. As compared with other members of polyomics, such as spatial genomics and epigenomics, which represent complex genomic and epigenomic signatures making their modification very difficult or impractical, spatial entropyomics represents a single value, the highest of which sits at the driver forefront of tumor mass.

This simplicity lends itself to modification and reversal towards the normal range by one of the many designs of programmable nano-machines. As such, a new era of cancer therapeutics, which started eighty years ago with nitrogen mustard, will be led by programmable nano-machines which would modify the master regulator network entropy of driver zone of tumor mass, so that the forward evolutionary move of tumor mass [30] would cease or slow down significantly and consequently turn cancer into one of the many manageable chronic diseases [31].

References

2. West J, Bianconi G, Severini S, Teschendorff AE. Differential network entropy reveals cancer system hallmarks. Scientific Reports. 2012 Nov 13;2(1):1-8.

3. Nijman SM. Perturbation-driven entropy as a source of cancer cell heterogeneity. Trends in Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;6(6):454-61.

4. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013 Jun 6;153(6):1194-217.

5. Aguado J, di Fagagna FD, Wolvetang E. Telomere transcription in ageing. Ageing Research Reviews. 2020 Sep 1;62:101115.

6. Hrstka R, Coates PJ, Vojtesek B. Polymorphisms in p53 and the p53 pathway: roles in cancer susceptibility and response to treatment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2009 Mar;13(3):440-53.

7. Einhorn J. Nitrogen mustard: the origin of chemotherapy for cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 1985 Jul 1;11(7):1375-8.

8. Zhang H, Chen J. Current status and future directions of cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Cancer. 2018;9(10):1773.

9. A Baudino T. Targeted cancer therapy: the next generation of cancer treatment. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. 2015 Mar 1;12(1):3-20.

10. Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu J, et al. Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer research: progress and perspectives. Journal of Hematology & Oncology. 2021 Dec;14(1):1-26.

11. Morash M, Mitchell H, Beltran H, Elemento O, Pathak J. The role of next-generation sequencing in precision medicine: a review of outcomes in oncology. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2018 Sep 17;8(3):30.

12. Gonçalves GA, Paiva RD. Gene therapy: advances, challenges and perspectives. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2017 Jul;15:369-75.

13. Ganesan A. Epigenetics: the first 25 centuries. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2018 Jun 5;373(1748):20170067.

14. Seo J, Jin D, Choi CH, Lee H. Integration of MicroRNA, mRNA, and protein expression data for the identification of cancer-related MicroRNAs. PLoS One. 2017 Jan 5;12(1):e0168412.

15. Aslam B, Basit M, Nisar MA, Khurshid M, Rasool MH. Proteomics: technologies and their applications. Journal of Chromatographic Science. 2017 Feb 1;55(2):182-96.

16. Dogra P, Butner JD, Chuang YL, Caserta S, Goel S, Brinker CJ, et al. Mathematical modeling in cancer nanomedicine: a review. Biomedical Microdevices. 2019 Jun;21(2):1-23.

17. Park Y, Lim S, Nam JW, Kim S. Measuring intratumor heterogeneity by network entropy using RNA-seq data. Scientific reports. 2016 Nov 24;6(1):1-2.

18. Sevick EM, Prabhakar R, Williams SR, Searles DJ. Fluctuation theorems. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem.. 2008 May 5;59:603-33.

19. Vargas-Rondón N, Villegas VE, Rondón-Lagos M. The role of chromosomal instability in cancer and therapeutic responses. Cancers. 2017 Dec 28;10(1):4.

20. Stanta G, Bonin S. Overview on clinical relevance of intra-tumor heterogeneity. Frontiers in Medicine. 2018 Apr 6;5:85.

21. Chen YJ, Dalchau N, Srinivas N, Phillips A, Cardelli L, Soloveichik D, et al. Programmable chemical controllers made from DNA. Nature Nanotechnology. 2013 Oct;8(10):755-62.

22. Youssef N, Budd A, Bielawski JP. Introduction to genome biology and diversity. Evolutionary Genomics. 2019:3-1.

23. Kabe Y, Sakamoto S, Hatakeyama M, Yamaguchi Y, Suematsu M, Itonaga M, et al. Application of high-performance magnetic nanobeads to biological sensing devices. Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry. 2019 Mar;411(9):1825-37.

24. Schwarz B, Uchida M, Douglas T. Biomedical and catalytic opportunities of virus-like particles in nanotechnology. Advances in Virus Research. 2017 Jan 1;97:1-60.

25. Savić N, Schwank G. Advances in therapeutic CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Translational Research. 2016 Feb 1;168:15-21.

26. Nedorezova DD, Fakhardo AF, Nemirich DV, Bryushkova EA, Kolpashchikov DM. Towards DNA nanomachines for cancer treatment: achieving selective and efficient cleavage of folded RNA. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2019 Mar 26;58(14):4654-8.

27. Shrestha B, Wang L, Brey EM, Uribe GR, Tang L. Smart nanoparticles for chemo-based combinational therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jun;13(6):853.

28. Pucci C, Martinelli C, Ciofani G. Innovative approaches for cancer treatment: Current perspectives and new challenges. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:961.

29. Beck S, Ng T. C2c: turning cancer into chronic disease. Genome Medicine. 2014 Dec;6(5):1-4.

30. Ho D, Wang P, Kee T. Artificial intelligence in nanomedicine. Nanoscale Horizons. 2019;4(2):365-77.

31. Herrera-Ibatá DM. Machine learning and perturbation theory machine learning (ptml) in medicinal chemistry, biotechnology, and nanotechnology. Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry. 2021 Apr 1;21(7):649-60.

32. Zhang XC, Li H. Interplay between the electrostatic membrane potential and conformational changes in membrane proteins. Protein Science. 2019 Mar;28(3):502-12.

33. Sidow A, Spies N. Concepts in solid tumor evolution. Trends in Genetics. 2015 Apr 1;31(4):208-14.

34. Arruebo M, Vilaboa N, Sáez-Gutierrez B, Lambea J, Tres A, Valladares M, et al. Assessment of the evolution of cancer treatment therapies. Cancers. 2011 Aug 12;3(3):3279-330.