Introduction

The introduction of neuromuscular blocking agents by Griffith and Johnson 83 years ago revolutionized anesthesia and surgical practices. Muscle relaxants are vital for facilitating endotracheal intubation, minimizing upper airway trauma, and creating optimal surgical conditions. However, the use of muscle relaxants and their reversal can lead to complications. This brief commentary aims to summarize the latest hot topics in neuromuscular blocking agents and their reversal, along with the associated complications. Additionally, we will discuss emerging pharmacological agents in neuromuscular blockade and novel reversal agents.

Complications Associated with Neuromuscular Blocking Agents

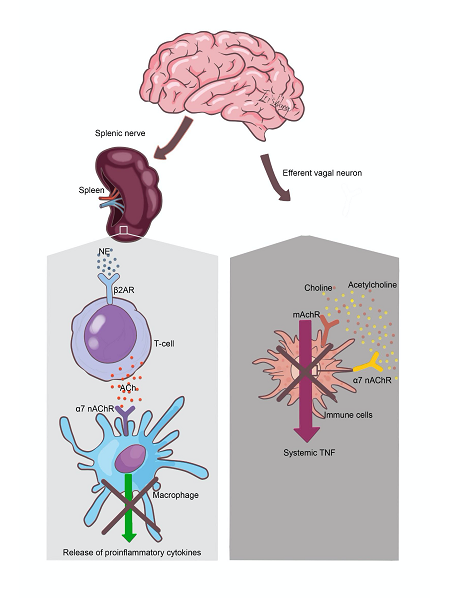

Inflammation is a typical response to surgical disturbances in homeostasis. The use of muscle relaxants may enhance the inflammatory response during surgery by inhibiting the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway. Macrophages are crucial in this inflammatory process, producing pro-inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukins (IL-1, IL-6). Excessive release of these mediators can lead to adverse outcomes, including diffuse tissue damage, hypotension, organ failure, and even death. The inflammatory response is counterbalanced by anti-inflammatory factors, including IL-10, IL-4, soluble TNF receptors, and other mediators.

The vagus nerve plays a significant role in this anti-inflammatory mechanism. Cytokines released at injury sites activate vagal afferent fibers, initiating an inflammatory reflex that stimulates vagal efferent fibers. This activation releases acetylcholine (ACh) at the distal end of the vagus nerve, which interacts with macrophages via α-7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (α7nAChR) to inhibit TNF-α and other pro-inflammatory cytokines. This anti-inflammatory pathway is known as the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway (CAP)[1–3].

Vagal nerve cholinergic activity is mediated through α7nAChR on macrophages, dendritic cells, and other immune cells. Activation of α7nAChR on macrophages reduces the release of inflammatory cytokines by inhibiting NF-κB promoter activity [4]. Electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve has been shown to suppress the inflammatory cascade triggered by NF-κB activation in the liver, reducing TNF levels and improving survival in models of hemorrhagic shock; vagotomy negates these effects [5]. Vagotomy has been associated with worsened pancreatitis and increased IL-6 levels, while treatment with the α7nAChR agonist GTS-21 alleviates pancreatitis severity[6]. Furthermore, subdiaphragmatic vagotomy has been linked to increased pancreatic cancer growth and reduced phagocytosis of E. coli by leukocytes, highlighting the importance of vagal cholinergic signals in resolving inflammation and limiting excessive pro-inflammatory responses [7,8].

Vagal nerve stimulation has emerged as a non-pharmacological treatment for TNF-α-related diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis [4]. The spleen, a major secondary lymphoid organ, is a significant reservoir for monocytes recruited to sites of inflammation and infection. Stimulation of the splenic nerve releases norepinephrine, which activates β2 receptors on cholinergic T cells, leading to ACh release and an anti-inflammatory response via α7nAChR on splenic macrophages (Figure 1) [2].

Figure 1. Cholinergic Anti-inflammatory Pathway Stimulation of the vagal afferents by peripheral injuries results in reflex arc stimulation of the vagal afferents that release ACh at α7nAChR on macrophages, thereby inhibiting release TNF-α. Simultaneous stimulation of vagal afferents leads to splenic nerve activation and release of NE at ß receptors in the cholinergic T cells in the spleen. The stimulated cholinergic T cells secrete ACh which inhibit release of TNF-α from splenic macrophages.

All neuromuscular blockers exert dose-dependent inhibition on human neuronal ACh receptors, including α7nAChR. This blockade may enhance inflammation and potentially increase the risk of postoperative complications [9].

A recent study found that neuromuscular blockade during general anesthesia is dose-dependently associated with a higher risk of postoperative delirium, although the administration of reversal agents may reduce this risk. These results underscore the inflammatory effects of muscle relaxants during surgery and the importance of complete reversal of their effects afterward [10].

Moreover, neuromuscular blockade is linked to an increased risk of residual paralysis, leading to postoperative pulmonary complications. Even mild residual blockade can impair pharyngeal muscle function, increasing the risk of aspiration pneumonia [11,12]. Neuromuscular blockers also indirectly contribute to postoperative hypoxemia by affecting carotid body nicotinic receptors [13].

The findings of the POPULAR study indicated that neuromuscular blocker use was associated with postoperative pulmonary complications in patients recovering from non-cardiac surgeries. Notably, neuromuscular blockers doubled the absolute incidence of postoperative pneumonia [14].

The introduction of sugammadex, a γ-cyclodextrin, has greatly enhanced the reversal of neuromuscular blocks induced by steroid-nucleus muscle relaxants such as rocuronium and vecuronium. Sugammadex forms a stable 1:1 complex with these agents, allowing for the encapsulation of free molecules in the vascular system, creating a concentration gradient that facilitates the restoration of nicotinic receptor function at the neuromuscular junction [15,16]. Approved in over 80 countries, sugammadex has been in clinical use in Europe since 2008 and in the U.S. since 2016. In addition, sugammadex was approved in 2024 for the reversal of neuromuscular blockade from rocuronium in children of all ages.

The use of sugammadex has shown to reduce the incidence of unplanned 30-day readmissions by 34% compared to neostigmine, with common causes for readmission being pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and fever [17].

However, its use is not without limitations, including ineffectiveness against benzylisoquinoline compounds and potential hypersensitivity and anaphylactic reactions (0.39%)[18]. Notably, it carries a tenfold higher risk of inducing severe hypersensitivity reactions compared to neostigmine, although such occurrences are rare [19].Other adverse effects may include bradycardia, hypotension, nausea, and interactions with other medications [20].

Sugammadex can bind factor Xa and prolong prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin time [21] or sex hormones [22], and thus can reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives.

Nonetheless, Georgakis et al. [23]. have reported complications associated with rocuronium and sugammadex compared to cisatracurium and neostigmine in patients with chronic kidney disease. A limitation of this study is that it did not specify the techniques used to guide muscle relaxant reversal. Incomplete reversal of neuromuscular blockers, especially aminosteriod agents like rocuronium, may inhibit the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, potentially exacerbating inflammatory responses and postoperative complications.

In patients with kidney disease, the duration of action for rocuronium is significantly prolonged compared to those with normal kidney function, which may further complicate reversal [24]. Conversely, cisatracurium is metabolized independently of kidney function, allowing for more effective elimination of its effects on the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway.

In our previous randomized controlled study, we found no significant difference in diaphragmatic contractility or pulmonary infection rates among patients undergoing neurointerventional procedures who received sugammadex or neostigmine, indicating that achieving a TOF ≥0.9 may be a more critical predictor of outcomes than the type of reversal agent [25].

In a recent retrospective cohort study involving patients who underwent general anesthesia with neuromuscular blockade in the bronchoscopy suite, we found a postoperative pulmonary complication rate of 2.7% for sugammadex and 1.9% for neostigmine. Although the absolute difference of 0.8% may not be clinically significant, it is important to note that sugammadex and neostigmine were chosen non-randomly, with many clinicians opting for neostigmine only when patients exhibited strong twitches [26].

In conclusion, the routine use of quantitative neuromuscular monitoring to ensure complete reversal of neuromuscular blockade may help prevent perioperative complications. Further randomized trials are necessary to accurately assess the impact of neuromuscular block reversal agent selection on postoperative respiratory complications.

New muscle relaxants

In the quest for ultrashort-acting neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs), a new class of nondepolarizing NMBAs known as asymmetric mixed-onium chlorofumarates has been developed. These molecules share a common bis-benzyltetrahydroisoquinolinium core structure. Gantacurium, along with its analogues CW002 and CW001, belongs to this new family. Despite promising results related to their mechanism of action and safety profile, none of these drugs are currently available for clinical use [27].

The metabolism of this new class of NMBAs involves pH-sensitive hydrolysis, a slow process, and cysteine adduction, a faster one. Cysteine adduction occurs when chloride is replaced by cysteine, leading to the formation of a heterocyclic ring that prevents interaction with the postjunctional acetylcholine receptor at the neuromuscular junction. Consequently, these new NMBAs can be reversed with the administration of cysteine. Cysteine is typically provided as part of parenteral nutrition and exists in both L- and D-enantiomers; however, only the L-enantiomer is effective as a reversal agent for this class of NMBAs [28]. It is important to note that L-cysteine adduction is not dependent on liver or kidney function, nor is it affected by pH and temperature.

Gantacurium

Gantacurium is an ultrashort muscle relaxant, with an effective dose in 95% of the population (ED95) of 0.19 mg/kg. Its onset of action occurs in less than 3 minutes at 1x ED95. When the dose is increased to 4x ED95, the onset time is reduced to 1.5 minutes, with a duration of action lasting 15 minutes. The dose of L-cysteine for gantacurium reversal is 10 mg/kg.

The resultants products of gantacurium metabolism are mostly excreted by the kidney and to lesser extent in the bile [29,30].

Gantaurium analogues, CW002 and CW001, are two to four times more potent than gantacurium, indicating that a smaller dose is required for neuromuscular blockade. Additionally, the adduction reaction occurs more slowly, resulting in a reversal dose of L-cysteine of 50 mg/kg for CW002 and CW001, compared to 10 mg/kg for gantacurium [27,30].

The ED95 of CW002 is 0.77 mg/kg. After administering a dose of 1.8x ED95, the onset of neuromuscular block occurs in approximately 90 seconds, with a duration of action of 33.8 minutes [16].

The ED95 dose of CW001 is 0.025 mg/kg, and the duration of action for a dose of 4x ED95 is 20.8 minutes [31].

New Generation of Neuromuscular Blockade Reversal Agents

Adamgammadex

Adamgammadex is a γ-cyclodextrin derivative featuring thiolated side chains of L-acetylcysteine, which replace the mercaptopropionic acid chains found in sugammadex. This modification enhances the binding affinity for rocuronium while reducing the risk of anaphylaxis associated with adamgammadex. The increased number of chiral carbon atoms in L-acetylcysteine limits the entry of rocuronium into the cyclodextrin core, thereby decreasing the likelihood of subsequent dissociation. This slower penetration into the adamgammadex core accounts for its 50% lower potency compared to sugammadex observed in phase II and early phase III clinical trials [32,33]. Additionally, the greater number of chiral carbon atoms in the L-acetylcysteine side chains, relative to sugammadex, is believed to enhance drug stability and minimize allergic reactions, given that L-acetylcysteine is an endogenous compound [20].

In preclinical trials, adamgammadex demonstrated a significantly reduced propensity for hypersensitivity reactions, including anaphylaxis, along with minimal adverse effects on cardiac and coagulation functions compared to sugammadex. A recent multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) indicated that the equipotent dose of adamgammadex (4 mg/kg) was non-inferior to sugammadex (2 mg/kg) in improving the quality of reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade, while also exhibiting a favorable safety profile [34]. However, there are concerns that the increased dosage required for equipotent reversal with adamgammadex may negate these benefits. A study involving 156 patients, which compared the efficacy of adamgammadex and sugammadex at higher dosages for reversing deep rocuronium-induced neuromuscular block, found no differences in the frequency of side effects [35]. It is possible that patients with an allergy to sugammadex will also react to adamgammadex because of the structural similarity between the two drugs [20].

Further research is necessary to support the potential approval of adamgammadex for clinical use.

Pillar [6]MaxQ and Calabadion 2

Pillar[6]MaxQ and Calabadion 2 can encapsulate not only steroidal neuromuscular blocking agents but also the benzylisoquinolinium blocking agent cisatracurium [36,37]. Additionally, Pillar[6]MaxQ exhibits a strong binding affinity for succinylcholine and gallamine [37]. In a recent study involving isoflurane-anesthetized rats, the equipotent doses of sugammadex and Pillar[6]MaxQ were compared regarding their effectiveness in reversing neuromuscular blockade induced by rocuronium or vecuronium. Both sugammadex and Pillar[6]MaxQ demonstrated similar recovery profiles [38]. However, Pillar[6]MaxQ exhibits over 20,000-fold higher affinity for neuromuscular blocking agents compared to sugammadex, which reduces the likelihood of displacement and subsequent recurarization [37].

Currently, there is no human data available regarding the allergenic potential of either Pillar[6]MaxQ or Calabadion 2.

Chloride channel blockers

Chloride channel 1 (CLC-1) is a voltage-gated chloride channel found in skeletal muscle membranes, playing a crucial role in stabilizing the resting membrane potential of skeletal muscle cells by facilitating chloride ion conductance. This function helps prevent excessive muscle depolarization [39]. Utilizing CLC-1 blockers presents a novel strategy to enhance muscle fiber excitability, rather than directly targeting neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) or acetylcholine receptors. This approach increases the responsiveness of muscle fibers to residual nerve signals, allowing for muscle contractions that counteract the effects of NMBAs [28].

In vivo studies conducted in anesthetized rats demonstrated that the CLC-1 blocker (compound A-3) at a dose of 13 mg/kg accelerated the recovery of both twitch and tetanic (sustained) force following neuromuscular blockade induced by aminosteroidal and benzylisoquinolinium agents. Furthermore, the reversal effects of CLC-1 (compound A-3) were observed to be faster than those of neostigmine in reversing neuromuscular blockade caused by rocuronium and cisatracurium [39,40].

Inhibition of CLC-1 represents a promising new mechanism for the rapid reversal of neuromuscular blockade; however, further research is needed to assess its clinical applicability.

Conclusion

Recently, ongoing research has revealed significant advancements in pharmacological agents for neuromuscular blockade and its reversal, however their use is still not without complications. Continued investigation will clarify the role of these novel agents in clinical practice.

References

2. Hoover DB. Cholinergic modulation of the immune system presents new approaches for treating inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2017 Nov;179:1–16.

3. Bonaz B, Sinniger V, Pellissier S. Anti-inflammatory properties of the vagus nerve: potential therapeutic implications of vagus nerve stimulation. J Physiol. 2016 Oct 15;594(20):5781–90.

4. Chavan SS, Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Relevance of Neuro-immune Communication. Immunity. 2017 Jun 20;46(6):927–42.

5. Guarini S, Altavilla D, Cainazzo MM, Giuliani D, Bigiani A, Marini H, et al. Efferent vagal fibre stimulation blunts nuclear factor-kappaB activation and protects against hypovolemic hemorrhagic shock. Circulation. 2003 Mar 4;107(8):1189–94.

6. Giebelen IA, van Westerloo DJ, LaRosa GJ, de Vos AF, van der Poll T. Local stimulation of alpha7 cholinergic receptors inhibits LPS-induced TNF-alpha release in the mouse lung. Shock. 2007 Dec;28(6):700–3.

7. Partecke LI, Käding A, Trung DN, Diedrich S, Sendler M, Weiss F, et al. Subdiaphragmatic vagotomy promotes tumor growth and reduces survival via TNFα in a murine pancreatic cancer model. Oncotarget. 2017 Apr 4;8(14):22501–12.

8. Dalli J, Colas RA, Arnardottir H, Serhan CN. Vagal Regulation of Group 3 Innate Lymphoid Cells and the Immunoresolvent PCTR1 Controls Infection Resolution. Immunity. 2017 Jan 17;46(1):92–105.

9. Jonsson M, Gurley D, Dabrowski M, Larsson O, Johnson EC, Eriksson LI. Distinct pharmacologic properties of neuromuscular blocking agents on human neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: a possible explanation for the train-of-four fade. Anesthesiology. 2006 Sep;105(3):521–33.

10. Ahrens E, Wachtendorf LJ, Shay D, Tenge T, Paschold BS, Rudolph MI, et al. Association Between Neuromuscular Blockade and Its Reversal With Postoperative Delirium in Older Patients: A Hospital Registry Study. Anesth Analg. 2025 Aug 1;141(2):363–72.

11. Farhan H, Moreno-Duarte I, McLean D, Eikermann M. Residual Paralysis: Does it Influence Outcome After Ambulatory Surgery? Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2014 Dec;4(4):290–302.

12. Ruscic KJ, Grabitz SD, Rudolph MI, Eikermann M. Prevention of respiratory complications of the surgical patient: actionable plan for continued process improvement. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2017 Jun;30(3):399–408.

13. Broens SJL, Boon M, Martini CH, Niesters M, van Velzen M, Aarts LPHJ, Dahan A. Reversal of Partial Neuromuscular Block and the Ventilatory Response to Hypoxia: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Healthy Volunteers. Anesthesiology. 2019 Sep;131(3):467–76.

14. Kirmeier E, Eriksson LI, Lewald H, Jonsson Fagerlund M, Hoeft A, Hollmann M, et al; POPULAR Contributors. Post-anaesthesia pulmonary complications after use of muscle relaxants (POPULAR): a multicentre, prospective observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2019 Feb;7(2):129–40.

15. Booij LH. Cyclodextrins and the emergence of sugammadex. Anaesthesia. 2009 Mar;64 Suppl 1:31–7.

16. Stäuble CG, Blobner M. The future of neuromuscular blocking agents. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020 Aug;33(4):490–8.

17. Oh TK, Oh AY, Ryu JH, Koo BW, Song IA, Nam SW, Jee HJ. Retrospective analysis of 30-day unplanned readmission after major abdominal surgery with reversal by sugammadex or neostigmine. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2019 Mar 1;122(3):370–8.

18. Miyazaki Y, Sunaga H, Kida K, Hobo S, Inoue N, Muto M, Uezono S. Incidence of Anaphylaxis Associated With Sugammadex. Anesth Analg. 2018 May;126(5):1505–8.

19. Harper NJN, Cook TM, Garcez T, Farmer L, Floss K, Marinho S, et al. Anaesthesia, surgery, and life-threatening allergic reactions: epidemiology and clinical features of perioperative anaphylaxis in the 6th National Audit Project (NAP6). Br J Anaesth. 2018 Jul;121(1):159–71.

20. Hunter JM, Blobner M. Developing novel drugs to reverse neuromuscular block: do we need them? Br J Anaesth. 2025 Jun;134(6):1591–6.

21. Rahe-Meyer N, Fennema H, Schulman S, Klimscha W, Przemeck M, Blobner M, et al. Effect of reversal of neuromuscular blockade with sugammadex versus usual care on bleeding risk in a randomized study of surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 2014 Nov;121(5):969–77.

22. Devoy T, Hunter M, Smith NA. A prospective observational study of the effects of sugammadex on peri-operative oestrogen and progesterone levels in women who take hormonal contraception. Anaesthesia. 2023 Feb;78(2):180–7.

23. Georgakis NA, DeShazo SJ, Gomez JI, Kinsky MP, Arango D. Risk of Acute Complications with Rocuronium versus Cisatracurium in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Propensity-Matched Study. Anesth Analg. 2025 May 1;140(5):1004–11.

24. Robertson EN, Driessen JJ, Vogt M, De Boer H, Scheffer GJ. Pharmacodynamics of rocuronium 0.3 mg kg(-1) in adult patients with and without renal failure. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2005 Dec;22(12):929–32.

25. Farag E, Rivas E, Bravo M, Hussain S, Argalious M, Khanna S, et al. Sugammadex Versus Neostigmine for Reversal of Rocuronium Neuromuscular Block in Patients Having Catheter-Based Neurointerventional Procedures: A Randomized Trial. Anesth Analg. 2021 Jun 1;132(6):1666–76.

26. Farag E, Shah K, Argalious M, Abdelmalak B, Gildea T, et al. Pulmonary complications associated with sugammadex or neostigmine in patients recovering from advanced diagnostic or interventional bronchoscopy: a retrospective two-centre analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2025 Jul;135(1):197–205.

27. de Boer HD, Carlos RV. New Drug Developments for Neuromuscular Blockade and Reversal: Gantacurium, CW002, CW011, and Calabadion. Curr Anesthesiol Rep. 2018;8(2):119–24.

28. de Boer HD, Vieira Carlos R. Next generation of neuromuscular blockade reversal agents. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Aug 1;38(4):337–42.

29. Belmont MR, Lien CA, Tjan J, Bradley E, Stein B, Patel SS, et al. Clinical pharmacology of GW280430A in humans. Anesthesiology. 2004 Apr;100(4):768–73.

30. Jankovic R, Stojanovic M, Nikolic A. Is there still a place for fast-acting neuromuscular blockade agents: fast onset or safe and prompt reversal? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2025 Aug 1;38(4):343–8.

31. Savarese JJ, McGilvra JD, Sunaga H, Belmont MR, Van Ornum SG, Savard PM, et al. Rapid chemical antagonism of neuromuscular blockade by L-cysteine adduction to and inactivation of the olefinic (double-bonded) isoquinolinium diester compounds gantacurium (AV430A), CW 002, and CW 011. Anesthesiology. 2010 Jul;113(1):58–73.

32. Zhang Y, Jiang Y, Lei Q, Li C, Jin S, Wang Q, et al. Phase III clinical trial comparing the efficacy and safety of adamgammadex with sugammadex for reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular block. Br J Anaesth. 2024 Jan;132(1):45–52.

33. Jiang YY, Zhang YJ, Zhu ZQ, Huang YD, Zhou DC, Liu JCet al. Adamgammadex in patients to reverse a moderate rocuronium-induced neuromuscular block. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022 Aug;88(8):3760–70.

34. Zhao Y, Chen S, Huai X, Yu Z, Qi Y, Qing J, et al. Efficiency and Safety of the Selective Relaxant Binding Agent Adamgammadex Sodium for Reversing Rocuronium-Induced Deep Neuromuscular Block: A Single-Center, Open-Label, Dose-Finding, and Phase IIa Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 25;8:697395.

35. Zhao Y, Ren Y, Xie W, Wang Y, Lei Y, Zhu Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of adamgammadex for reversing rocuronium-induced deep neuromuscular block: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, positive-controlled phase III trial. Br J Anaesth. 2025 Aug;135(2):331–9.

36. Haerter F, Simons JC, Foerster U, Moreno Duarte I, Diaz-Gil D, Ganapati S, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Calabadion and Sugammadex to Reverse Non-depolarizing Neuromuscular-blocking Agents. Anesthesiology. 2015 Dec;123(6):1337–49.

37. Zhang W, Bazan-Bergamino EA, Doan AP, Zhang X, Isaacs L. Pillar [6] MaxQ functions as an in vivo sequestrant for rocuronium and vecuronium. Chemical Communications. 2024;60(32):4350–3.

38. Cotten JF, Isaacs L. Pillar[6]MaxQ and Sugammadex Enhance Recovery From Rocuronium- and Vecuronium-Mediated Neuromuscular Blockade With Similar Effects in Isoflurane-Anesthetized Rats. Anesth Analg. 2025 Jan 28;140(6):1495–7.

39. Pedersen SS, Holse C, Mathar CE, Chan MTV, Sessler DI, Liu Y, et al. Intraoperative Inspiratory Oxygen Fraction and Myocardial Injury After Noncardiac Surgery: Results From an International Observational Study in Relation to Recent Controlled Trials. Anesth Analg. 2022 Nov 1;135(5):1021–30.

40. Skals M, Broch-Lips M, Skov MB, Riisager A, Ceelen J, Nielsen OB, et al. ClC-1 Inhibition as a Mechanism for Accelerating Skeletal Muscle Recovery After Neuromuscular Block in Rats. Nat Commun. 2024 Oct 28;15(1):9289.