Abstract

A-to-I RNA modifications performed by the adenosine deaminase acting on RNA (ADAR) protein family are gaining traction as important mechanisms in cancer biology. A-to-I RNA editing changes adenosine to inosine on double stranded RNA, which co-transcriptionally alters transcript sequence and structure. A number of microRNA (miRNA) precursors are known to be edited by the ADARs, which alters the expression and/or function of the mature miRNA. A-to-I editing levels are high in thyroid tumors, but the ADAR-editase mechanisms governing thyroid cancer progression are unexplored. We recently demonstrated a functional role for ADAR1 and RNA editing in thyroid cancer, as shown by the suppression of tumorigenesis in vitro and in vivo following ADAR1 gene silencing. We also dissected the mechanism of action underlying this process in thyroid tumorigenesis and found that editing of the miRNA miR-200b is responsible, at least in part, for the aggressive features induced by ADAR1. Importantly, this editing event is overrepresented in thyroid tumors, and correlates with a worse progression-free survival and disease stage. Lastly, our results underscore the potential benefits of inhibiting RNA editing as a future treatment for advanced thyroid cancer, as pharmacological inhibition of ADAR1 editase activity with 8-azaadenosine reduced cancer cell aggressiveness in a heterotopic xenograft model. Overall, our study highlights the importance of miRNA editing in gene regulation and suggests its potential as a biomarker for thyroid cancer prognosis and therapy.

Concept of RNA Editing

RNA editing is a major co-transcriptional mechanism to modify specific nucleotides in RNA molecules, generating informational diversity. The most common type of RNA editing in mammals is adenosine to inosine (A-to-I) editing, which is mediated by the ADAR (adenosine deaminase acting on RNA) family of enzymes [1]. ADAR enzymes catalyze the recoding of A to I by hydrolytic deamination in double-stranded RNA molecules. The translation machinery then decodes I as guanosine (G), base-pairing with cytosine (C). Accordingly, A-to-I editing is similar to an A-to-G substitution without altering the DNA template and changing only a portion of RNAs. The ADAR enzyme family dynamically regulates RNA editing in cells: ADAR1, ADAR2 and ADAR3. Interestingly, whereas ADAR1 and ADAR2 are active enzymes, ADAR3 is reported to be catalytically inactive [2]. Aberrant RNA editing has been linked to several diseases, including cancer, through mechanisms that are poorly understood. In diseases such as cancer, aberrant RNA editing skews the balance between edited and wild-type RNAs, resulting not only in protein changes through missense codon change or alternative splicing in the case of coding RNAs, but also changing the stability and function of non-coding RNAs, including microRNAs (miRNAs) [3,4]. The focus of our recent work was the oncogenic role of ADAR1 in thyroid cancer [5].

MicroRNA Editing

miRNAs are small non-coding RNAs of ~22 nucleotides that suppress gene expression through interactions of their seed region with complementary sequences in the 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) of target messenger RNAs (mRNAs), and thus function as post-transcriptional regulators [6]. miRNAs participate in the transcriptional circuits of many cellular pathways and control important cell processes such as apoptosis, development, proliferation and differentiation. They can also participate in pathological processes such as oncogenesis, acting both as tumor suppressors and as oncogenes. Accordingly, miRNAs have been widely studied as potential biomarkers for diagnosis, cancer subtype classification, prognosis and therapy in different cancers [7-9].

Because of their critical role in gene regulation, miRNAs are frequently altered in cancer, not only at the level of their expression but also their nucleotide sequence by RNA editing. In some contexts, editing of a primary miRNA can affect its biogenesis, to inhibit miRNA maturation. Alternatively, as miRNA regulation requires the base-pairing of sequences, editing can alter the recognition of the target mRNA, particularly when it occurs within the seed sequence of the miRNA [10]. Because miRNAs can act both as tumor promoters and as suppressors, it might be hypothesized that editing processes could result in opposing outcomes depending on the specific miRNA. Several editing events appear to be critical in different cancers. For example, in metastatic melanoma, the biological function of miR-455-5p is dependent on its editing status, which can change the suite of genes recognized. Functionally, edited miR-455-5p inhibits melanoma growth and metastasis, whereas the wild-type form promotes these features by inhibiting the tumor suppressor CPEB1 (cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein 1) [11]. In glioma, miR-376a accumulates entirely in an unedited form, whereas in normal states miR-376a is edited. Edited miR-376a is unable to suppress its cognate target RAP2A, and instead gains the ability to target AMFR, overall having a pro-invasive effect [12]. However, miRNA editing does not always induce miRNA re-targeting; for instance, in glioblastoma it was found that the editing of oncogenic miR-221, miR-222, and miR-21 inhibits their maturation, leading to a decrease in the expression of the corresponding mature miRNAs, with important effects on tumor cell behavior [13].

Role of RNA Editing in Cancer

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Consortium has recently provided the full transcriptome of various cancer types, allowing the RNA-editing genomic landscape to be systematically characterized and compared with that of normal genomes [14-16]. These studies identified widespread and reproducible A-to-I editing-specific events and revealed that A-to-I editing and associated enzymes are significantly altered, typically elevated, in most cancer types, with the strongest levels reported thus far in breast, thyroid, and head and neck cancers. Importantly, increased editing activity has been found to be negatively associated with patient survival [14,15], and other studies have demonstrated that ADAR1-mediated RNA editing is a dominant driver of cancer relapse and progression [17-19]. Indeed, ADAR1 is an established oncogene in several tumor types including oral cancer [20], cervical cancer (HeLa cells) [21], lung cancer [22], and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [19]. The functional impact of ADAR1 expression and the underlying mechanisms remain, however, enigmatic.

Role of RNA editing in thyroid cancer

Despite the fact that thyroid tumors have one of the highest levels of RNA editing activity when compared with matched normal tissue, we were surprised that no functional studies of this process had been conducted. Thyroid cancer is the most common endocrine malignancy [23] and its incidence has rapidly increased in the last few decades [24-26]. In general terms, thyroid cancer has a good prognosis [27], as the majority of the patients can be cured by thyroidectomy (removing all or part of the thyroid) followed by radioiodine ablation. However, a small number of patients develop aggressive forms of the disease that are refractory to radioactive iodine treatment, and their life expectancy is short. The molecular basis of aggressive thyroid cancer progression is not well understood and there remains an urgent need to develop new effective therapies. Our recent study [5] sheds some light on the mechanisms underlying this process, and reveals that beyond genomic mutations, reprogramming by RNA modifications adds another layer of molecular complexity to thyroid cancer cells. Supporting the findings in other types of cancer [17-22], we found that ADAR1 plays a role in the tumorigenic behavior of thyroid cancer cells. Indeed, ADAR1 loss-of-function in three different thyroid cancer cell lines impeded cell proliferation, migration, invasion and three-dimensional (3D) growth. This latter result is important as 3D models can accurately recreate the complexity and heterogeneity of tumors. We confirmed these observations in vivo and showed that tumor growth was significantly delayed in ADAR1-silenced tumors in a heterotopic xenograft mouse model. An important translational aspect of our study is the finding that the inhibition of ADAR1-dependant RNA editing using the small molecule 8-azaadenosine (8-aza) decreased cancer aggressiveness, an effect evident in both 2D and 3D cultures. Although it is likely that this molecule needs to be improved to minimize its adverse effects [28], we propose RNA editing as a tractable therapeutic target for thyroid cancer.

ADAR1 mechanism of action in thyroid cancer

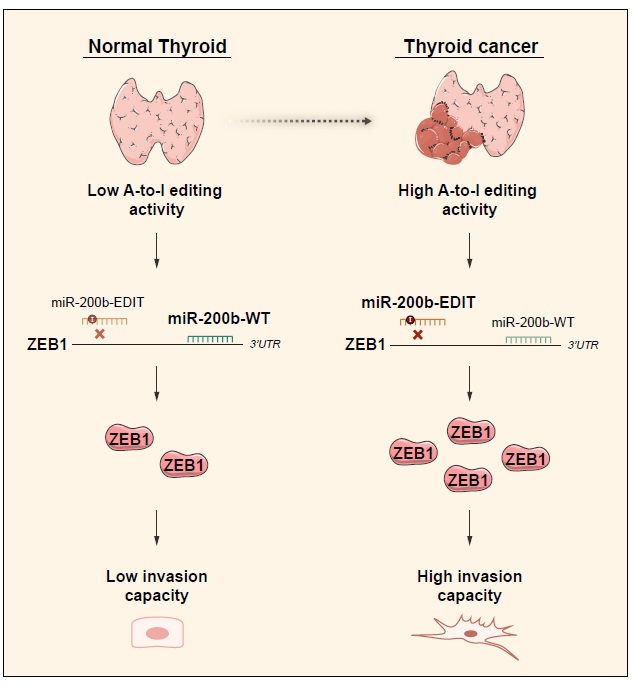

Our results underscore ADAR1 overexpression as an oncogenic event in thyroid cancer. Whether the resulting RNA editing plays a causative role in thyroid tumor progression, however, remains an open question. To address this limitation, we focused on an RNA-editing event that occurs in the seed region of miR-200b, an event that is overrepresented in thyroid tumors compared with normal tissues of the TCGA cohort [16]. Although little is known about miR-200b in thyroid cancer, it has been reported to be exclusively downregulated in the most aggressive form of the disease – anaplastic thyroid carcinoma [29] – suggesting a role in cancer progression. Interestingly, miR-200b has been described as an important tumor suppressor miRNA in other tissues and it is under intensive clinical investigation as a therapeutic cancer target [30]. Moreover, miR-200b is a known suppressor of epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) by inhibiting key regulators such as the transcriptional repressor ZEB1 [31]. ZEB1 is an important activator of EMT during embryonic development and in cancer. It suppresses E-cadherin transcription and the expression of basement membrane components and cell polarity proteins [32] Studies of thyroid carcinomas have shown an increased expression of ZEB1 [32,33] in this cancer type. Indeed, its overexpression was associated with aggressive features such lymph node and distant metastasis [33]. By analyzing the edited and wild-type levels of miR-200b in six thyroid cancer patients, we confirmed that miR-200b is over edited, and found a significant increase in the edited/wild-type ratio in tumor samples. Of clinical relevance, TCGA data reveal a strong correlation between miR-200b editing levels and worse progression-free survival [16]. We found that the edited form of miR-200b has weakened activity against its target gene ZEB1, likely explaining the reduced aggressiveness of ADAR1-silenced thyroid cells [5]. Thus, our data strongly suggest that induction of miR-200b editing, by increasing the ADAR1-dependent RNA editing activity in thyroid cancer cells, is an additional strategy to increase ZEB1 levels and thus stimulate EMT, ultimately leading to an increase in their motility and invasion features (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic summary of the proposed mechanism for the ADAR1-induced thyroid tumorigenesis. In the thyroid tissue, the ADAR1-dependent A-to-I editing activity is low, thus founding miR-200b mainly in its wildtype (WT) form. This miRNA is able to inhibit ZEB1 maintaining low levels of this protein and the low invasion capacity of the thyroid cells. However, in the cancerous state, the ADAR1 A-to-I editing activity is high, allowing the editing of miR-200b. The edited miR-200b presents an impaired ability to inhibit ZEB1, increasing the levels of this protein and therefore increasing the invasion capacity of the thyroid cancer cells.

Conclusions

The inhibition of ADAR1 expression and A-to-I RNA editing affects thyroid cancer aggressiveness impairing proliferation, invasion and migration. The molecular mechanism encompasses the tumor suppressor miR-200b, which is over-edited in thyroid tumors weakening its ability to inhibit ZEB1. In conclusion, ADAR1 acts as an oncogene in thyroid cancer and is a new potential therapeutic target.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Kenneth McCreath for his comments on the manuscript and for his linguistic assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by grants SAF2016-75531-R from Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MICIN), Spain, Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional FEDER, B2017/BMD-3724 from Comunidad de Madrid, and GCB14142311CRES from Fundación Española contra el Cáncer (AECC) JR-M hold a FPU fellowship from MECD (Spain).

References

2. Chen CX, Cho DS, Wang Q, Lai F, Carter KC, Nishikura K. A third member of the RNA-specific adenosine deaminase gene family, ADAR3, contains both single- and double-stranded RNA binding domains. RNA. 2000;6(5):755-67.

3. Li JB, Levanon EY, Yoon JK, Aach J, Xie B, Leproust E, et al. Genome-wide identification of human RNA editing sites by parallel DNA capturing and sequencing. Science. 2009;324(5931):1210-3.

4. Wang Y, Liang H. When MicroRNAs Meet RNA Editing in Cancer: A Nucleotide Change Can Make a Difference. Bioessays. 2018;40(2).

5. Ramírez-Moya J, Baker AR, Slack FJ, Santisteban P. ADAR1-mediated RNA editing is a novel oncogenic process in thyroid cancer and regulates miR-200 activity. Oncogene. 2020.

6. Lin S, Gregory RI. MicroRNA biogenesis pathways in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2015;15(6):321-33.

7. Tassinari V, Cesarini V, Silvestris DA, Gallo A. The adaptive potential of RNA editing-mediated miRNA-retargeting in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. 2019;1862(3):291-300.

8. Rupaimoole R, Slack FJ. MicroRNA therapeutics: towards a new era for the management of cancer and other diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2017;16(3):203-22.

9. Heneghan HM, Miller N, Kerin MJ. MiRNAs as biomarkers and therapeutic targets in cancer. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(5):543-50.

10. Nishikura K. A-to-I editing of coding and non-coding RNAs by ADARs. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2016;17(2):83-96.

11. Shoshan E, Mobley AK, Braeuer RR, Kamiya T, Huang L, Vasquez ME, et al. Reduced adenosine-to-inosine miR-455-5p editing promotes melanoma growth and metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(3):311-21.

12. Choudhury Y, Tay FC, Lam DH, Sandanaraj E, Tang C, Ang BT, et al. Attenuated adenosine-to-inosine editing of microRNA-376a* promotes invasiveness of glioblastoma cells. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(11):4059-76.

13. Tomaselli S, Galeano F, Alon S, Raho S, Galardi S, Polito VA, et al. Modulation of microRNA editing, expression and processing by ADAR2 deaminase in glioblastoma. Genome Biol. 2015;16:5.

14. Han L, Diao L, Yu S, Xu X, Li J, Zhang R, et al. The Genomic Landscape and Clinical Relevance of A-to-I RNA Editing in Human Cancers. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(4):515-28.

15. Paz-Yaacov N, Bazak L, Buchumenski I, Porath HT, Danan-Gotthold M, Knisbacher BA, et al. Elevated RNA Editing Activity Is a Major Contributor to Transcriptomic Diversity in Tumors. Cell Rep. 2015;13(2):267-76.

16. Wang Y, Xu X, Yu S, Jeong KJ, Zhou Z, Han L, et al. Systematic characterization of A-to-I RNA editing hotspots in microRNAs across human cancers. Genome Res. 2017;27(7):1112-25.

17. Jiang Q, Crews LA, Barrett CL, Chun HJ, Court AC, Isquith JM, et al. ADAR1 promotes malignant progenitor reprogramming in chronic myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(3):1041-6.

18. Qi L, Chan TH, Tenen DG, Chen L. RNA editome imbalance in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(5):1301-6.

19. Qin YR, Qiao JJ, Chan TH, Zhu YH, Li FF, Liu H, et al. Adenosine-to-inosine RNA editing mediated by ADARs in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2014;74(3):840-51.

20. Liu X, Fu Y, Huang J, Wu M, Zhang Z, Xu R, et al. ADAR1 promotes the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem-like cell phenotype of oral cancer by facilitating oncogenic microRNA maturation. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):315.

21. Wang H, Hou Z, Wu Y, Ma X, Luo X. p150 ADAR1 isoform involved in maintenance of HeLa cell proliferation. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:282.

22. Gannon HS, Zou T, Kiessling MK, Gao GF, Cai D, Choi PS, et al. Identification of ADAR1 adenosine deaminase dependency in a subset of cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):5450.

23. Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(12):2893-917.

24. Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, Check D, Kitahara CM. Trends in Thyroid Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(13):1338-48.

25. Safavi A, Azizi F, Jafari R, Chaibakhsh S, Safavi AA. Thyroid Cancer Epidemiology in Iran: a Time Trend Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(1):407-12.

26. Carlberg M, Hedendahl L, Ahonen M, Koppel T, Hardell L. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the Nordic countries with main focus on Swedish data. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:426.

27. Xing M. Molecular pathogenesis and mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(3):184-99.

28. Spremulli EN, Cummings FJ, Crabtree GW, LaBresh K, Jordan M, Calabresi P. Hemodynamic effects of potentially useful antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983;70(3):499-504.

29. Braun J, Hoang-Vu C, Dralle H, Hüttelmaier S. Downregulation of microRNAs directs the EMT and invasive potential of anaplastic thyroid carcinomas. Oncogene. 2010;29(29):4237-44.

30. Feng X, Wang Z, Fillmore R, Xi Y. MiR-200, a new star miRNA in human cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;344(2):166-73.

31. Díaz-López A, Moreno-Bueno G, Cano A. Role of microRNA in epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis and clinical perspectives. Cancer Manag Res. 2014;6:205-16.

32. Montemayor-Garcia C, Hardin H, Guo Z, Larrain C, Buehler D, Asioli S, et al. The role of epithelial mesenchymal transition markers in thyroid carcinoma progression. Endocr Pathol. 2013;24(4):206-12.

33. Zhang Y, Liu G, Wu S, Jiang F, Xie J, Wang Y. Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1: its clinical significance and functional role in human thyroid cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:1303-10.