Abstract

WHIM (Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections, and Myelokathexis) syndrome is a rare primary immunodeficiency disorder characterized by susceptibility to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. WHIM syndrome is caused by a gain-of-function mutation CXCR4, leading to increased responsiveness of neutrophils and lymphocytes to CXCL12. This results in an accumulation of atypical hypersegmented mature neutrophils in the bone marrow and peripheral blood neutropenia. This case report discusses a 10-year-old girl who was diagnosed with WHIM syndrome at the age of four years following Haemophilus influenzae meningitis. She was found to have Tetralogy of Fallot at birth, which was surgically repaired when she was one year old. She was also found to have significant neutropenia during surgery and received multiple doses of G-CSF with a good response. She presented to the hospital at the age of four years with fever, neck stiffness, lethargy, and headache and was diagnosed with H. influenzae meningitis. Her immunology workup revealed significant neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia, as well as low antibody levels to H. influenza type B, tetanus toxoid, and Streptococcus pneumonia, despite up-to-date vaccination. Furthermore, decreased levels of T cells and B cells were detected. The patient was started on IgG replacement therapy and Bactrim prophylaxis. Bone marrow biopsy revealed granulocytic hyperplasia and occasional hypersegmented neutrophils, suggesting myelokathexis. Genetic testing revealed a heterozygous CXCR4 mutation with a premature stop codon (p.Ser338Ter), confirming the diagnosis of WHIM syndrome. This case report highlights the association of WHIM syndrome with congenital heart defects, such as Tetralogy of Fallot. A literature review revealed three other cases of congenital heart defects in patients with WHIM syndrome, indicating a potential role for CXCR4 and CXCL12 in septum formation. The rarity of the disorder and the lack of a universal screening tool makes the diagnosis of WHIM syndrome difficult. Therefore, physicians should consider WHIM syndrome in patients with congenital heart defects, particularly if they have recurrent HPV infections, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Keywords

WHIM syndrome, CXCR4, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Myelokathexis, Tetralogy of Fallot

Introduction

WHIM (Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections, and Myelokathexis) syndrome is a rare primary immunodeficiency disorder characterized by susceptibility to human papillomavirus (HPV) infections, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia [1,2]. WHIM syndrome is caused by heterozygous gain of function mutation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4, leading to increased responsiveness of neutrophils and lymphocytes to CXCL12 [3-5]. As a result, these cells are abnormally retained in the bone marrow, leading to an accumulation of atypical hypersegmented mature neutrophils in the bone marrow (also known as myelokathexis) with peripheral blood neutropenia [6]. These patients also have an increased risk of disseminated warts and cervical cancer due to HPV susceptibility. In addition, some patients have B cells dysfunction evident in B-cell lymphopenia with a reduced number of switched memory (CD27+) B cells, hypogammaglobulinemia, and poor vaccine response [7-9]. Diagnosis of WHIM syndrome can be delayed for several reasons. One reason is that the disorder is rare, with an incidence of less than one case per million births [10], which can lead to a lack of familiarity among the primary physician. Additionally, infections associated with WHIM syndrome are not always severe or life-threatening and may take a long time for a consistent pattern of vulnerability to be identified. For example, warts typically appear at older ages [11]. However, early diagnosis can be made through screening in selected cases of newborn TREC (T cell receptor excision circles) [12].

In addition to its typical features, WHIM syndrome has been associated with congenital heart disease in some case reports [13]. Furthermore, studies in mice have shown that defects in CXCR4 or CXCL12 can result in cardiac defects, suggesting a potential role for these genes in septum formation [14,15]. Herein we describe a case report of a patient with WHIM syndrome who presented with Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) and a literature review for other cases of congenital heart defects in patients with WHIM.

Case Presentation

The patient is a ten-year-old girl diagnosed with WHIM syndrome at four years of age after presenting with H. influenzae meningitis. She was diagnosed with ToF at birth in an outside hospital and was surgically corrected at the age of 1 year. At that time, she was found to have significant neutropenia and received multiple doses of G-CSF with a good response. Unfortunately, the cause of neutropenia was not identified, and the family lost to follow-up. Over the next few years, she had 3-4 episodes of ear infection in the first few years of life and recurrent viral infections but no history of pneumonia or warts. Her growth has been normal. At the age of 4 years, she presented to the hospital with several days of fever, neck stiffness, lethargy, and headache. She was found to have H. influenzae meningitis. During that hospitalization, she developed HSV-1 perioral blisters, similar to lesions found on her mother at the same time.

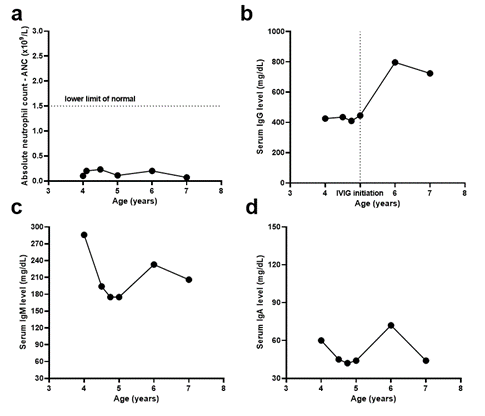

The patient was referred to Immunology due to her history of hypogammaglobulinemia and recent meningitis. Initial laboratory evaluation revealed a decreased number of CD8+ T cells and CD19+ B cells and normal CD4+ T cells and NK cells (Table 1). She also had elevated IgM (286 mg/dL), low IgG (426 mg/dL), normal IgE, and IgA (Table 1, Figure 1). Haemophilus influenza antibody levels were low (0.22) but increased significantly after booster vaccination (>9.0). Although the patient's Streptococcus pneumoniae antibody levels were protective for only three of 23 serotypes, the patient responded well to Pneumovax and achieved protective antibody levels for 20 of 23 serotypes. CD40 receptor expression, microarray testing, and anti-neutrophil antibody testing were all normal. Further testing six weeks later showed decreased T cell subsets (CD4+ T cells <400, CD8+ T cells <250) and CD19+ B cells, with normal NK cell count. The patient was prescribed prophylactic Bactrim and underwent a bone marrow biopsy, revealing granulocytic hyperplasia and occasional hypersegmented neutrophils, possibly indicating myelokathexis or autoimmune neutropenia. Given the combination of hypogammaglobulinemia and possible myelokathexis, WHIM (warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis) syndrome was suspected. A genetic test confirmed a heterozygous mutation in CXCR4 (p.Ser338Ter) that has been shown to be deleterious in prior studies [13,16-18]. The patient received IgG replacement therapy and intermittent G-CSF for six years, experiencing relatively infrequent infections. The patient did not develop warts till the time of this report.

Figure 1:The procedure used in this review to select the studies.

|

Immunologic Phenotype |

Normal range |

Laboratory results |

|

White blood cell - WBC |

5.0-14.5 x 109/L |

1.69 x 109/L |

|

Absolute neutrophil count - ANC |

1.5-8.1 x 109/L |

0.101 x 109/L |

|

Absolute lymphocyte count - ALC |

1.2-7.8 x 109/L |

1.487 x 109/L |

|

Absolute monocyte count - AMC |

0.2-1.5 x 109/L |

0.068 x 109/L |

|

Lymphocyte Phenotype |

||

|

CD3% (pan T-cells) |

54 -79% |

57 |

|

CD3 absolute count |

1,051-3,031/mm3 |

832 |

|

CD3+CD4+% (T-helper cell) |

28-49% |

40 |

|

CD3+CD4+ absolute count |

548-1,720/mm3 |

587 |

|

CD3+CD8+% (T- cytotoxic cells) |

17-32% |

13 |

|

CD3+CD8+ absolute count |

332-1,307/mm3 |

187 |

|

CD4/CD8 ratio |

0.98-2.51 |

3.1 |

|

CD19% (pan B-cells) |

9-32% |

6 |

|

CD19 absolute count |

203-1,139/mm3 |

87 |

|

CD3-CD16CD56+% (NK cells) |

6-25% |

36 |

|

CD3-CD16CD56+ absolute count |

138-1,027/mm3 |

528 |

|

B-cell Phenotype |

||

|

Naïve B cells (CD19+CD27-IgD+) |

54.85-96.02% of B Cells |

59.76 |

|

Marginal Zone B cells (CD19+CD27+IgD+) |

0.65-11.96% of B Cells |

36.26 |

|

Class Switched Memory B cells (CD19+CD27+IgD-) |

1.14-26.87% of B Cells |

2.73 |

|

Plasmablasts/Plasmacells (CD19+CD38highCD27high) |

0.00-4.23% of B Cells |

0.40 |

|

Immunoglobulins |

||

|

Immunoglobulin G (IGG) |

445-1,187 mg/dL |

426 |

|

Immunoglobulin M (IGM) |

41-186 mg/dL |

286 |

|

Immunoglobulin E (IGE) |

<142 KU/L |

10.8 |

|

Immunoglobulin A (IGA) |

25-153 mg/dL |

60.0 |

Literature Review

A literature search was conducted on PubMed to identify cases of WHIM syndrome associated with ToF using the following keywords: Tetralogy of Fallot and WHIM. Three other cases were identified in addition to our case (Table 2). Of note, some patients were reported in multiple publications. Genetic studies were carried out on these cases, and the most frequent mutation identified was p.Ser338Ter, followed by R334X mutation.

|

Patient number |

P1 (our case) |

P2 |

P3 |

P4 |

|

Mutation (CXCR4) |

p.Ser338Ter |

p.Ser338Ter |

p.Arg334 Ter |

p.Ser338Ter |

|

Age at molecular diagnosis |

4y |

19y |

5y |

6w (neutropenia and affected father) |

|

Clinical manifestations at onset |

H. influenzae meningitis |

TOF |

TOF |

TOF; neutropenia |

|

Neutropenia |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Myelokathexis |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

Hypogammaglobulinemia (age at onset) |

+ (4y) |

- |

+ (5y) |

+ |

|

Warts |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

|

Recurrent infections |

Ear infection, viral infection |

Pneumonia |

Pneumonia |

- |

|

Medical treatment |

G-CSF, antibiotic prophylaxis, IVIG |

G-CSF, antibiotic prophylaxis |

G-CSF, antibiotic prophylaxis |

IVIG |

|

congenital heart defects |

TOF associated with the presence of patent ductus arteriosus |

TOF |

TOF |

TOF |

|

Age at surgical correction |

1y |

1y |

2y |

2.5 m |

Case 2: 19-year-old male who was diagnosed with WHIM syndrome at 2.5 years old after experiencing severe neutropenia, recurrent pneumonia infections, and bronchiectasis. The bone marrow biopsy showed myelokathexis. Sequencing of the CXCR4 gene revealed p.Ser338Ter mutation. The patient also had TOF with pulmonary atresia, agenesis of the left-hand fingers, and hypoplasia of the radius on the same side. The patient was treated with subcutaneous injections of granulocyte-colony stimulating factor therapy [13].

Case 3: 15-year-old female patient who had TOF at birth, which was surgically corrected at the age of 2 years. The patient had recurrent respiratory infections since childhood, and severe neutropenia was diagnosed at the age of 2 years. The bone marrow biopsy showed myelokathexis. Sequencing of the CXCR4 gene revealed p.Arg334 Ter mutation. She was treated with granulocyte-colony stimulating factor therapy, and antibiotic prophylaxis was given to prevent pneumonia episodes. The patient later developed a plantar wart and hypogammaglobulinemia [13,19,20].

Case 4: 8.6-year-old male with ToF underwent a surgical correction in the first month of life. Neutropenia and hypogammaglobulinemia were present since infancy, and a bone marrow biopsy revealed myelokathexis. Genetic analysis of the CXCR4 gene showed p.Ser338Ter, which was shared with three other family members with neutropenia and recurrent infections but no congenital heart defect. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy effectively controlled infectious episodes [13,18].

Discussion

This study presents a case of a 10-year-old girl with WHIM syndrome and ToF, along with a review of three other cases of WHIM associated with ToF. Our patient was diagnosed with WHIM syndrome at the age of 4 years following H. influenzae meningitis infection. She had ToF at birth and was found to have significant neutropenia at the time of surgery. Unfortunately, the cause of her neutropenia was not identified, and a genetic test was not ordered. This highlights a gap in the knowledge in some pediatric centers about the many genetic diseases that can cause congenital neutropenia and cardiac disorders, such as WHIM syndrome, Atelis syndrome-2 [21], Dursun syndrome [22], Tiiac syndrome [23] and Barth syndrome [24]. In addition to the importance of genetic testing for accurate diagnosis and management of congenital neutropenia, it is particularly crucial in the case of WHIM syndrome due to the potential for targeted therapy with CXCR4 inhibitors [25,26]. With the emergence of CXCR4-targeted therapy, early diagnosis of WHIM syndrome through genetic testing can facilitate prompt initiation of therapy, which may improve outcomes and prevent complications. Therefore, it is recommended that genetic testing be considered in all pediatric patients with primary neutropenia disorders, especially in cases where targeted therapies are available or under development [27].

Although the TRECs newborn screening program can potentially diagnose WHIM syndrome, its significant rate of false negatives renders it less than ideal for screening [12]. As a result, physicians must be aware of early symptoms of WHIM syndrome, such as neutropenia, lymphopenia, and congenital heart defects [11] to facilitate early diagnosis and prevent complications such as meningitis and hearing loss, as was the case with our patient. Additionally, an Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Model has estimated a potential prevalence of 1800-3700 patients in the United States who exhibit a WHIM-like phenotype, a much higher estimate than the approximately 100 reported cases of WHIM in the literature [28].

Although the exact mechanism by which WHIM syndrome causes congenital heart defects is not fully understood, studies using mouse models of CXCR4 defects have demonstrated the development of these defects [14,15]. In our review, we identified three other cases of Tetralogy of Fallot in patients with WHIM syndrome [13], which is a significant number given the rarity of WHIM syndrome. In contrast, the incidence of ToF in the general population is 3 in 10,000 live births [29]. Interestingly, two specific mutations, p.Ser338Ter (present in three of the cases) and p.Arg334Ter (present in one of the cases) were found to be associated with Tetralogy of Fallot. This suggests that premature termination of the protein at these locations may influence septal formation in utero. However, it is unlikely that this influence is direct, as there are reports of WHIM patients with the p.Ser338Ter mutation who did not have Tetralogy of Fallot [13]. Instead, it is possible that the mutations influence the balance of CXCR4 and CXCR7 effects on cell responses to CXCL12 [13]. This case highlights the need for physicians to consider WHIM syndrome in patients with congenital heart defects, particularly if they have recurrent HPV infections, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia.

Conclusion

WHIM syndrome is a rare primary immunodeficiency disorder that can be difficult to diagnose due to its rarity and variable presentation. This case report highlights the association between WHIM syndrome and congenital heart defects such as Tetralogy of Fallot. Physicians should consider WHIM syndrome in patients with congenital heart defects, recurrent HPV infections, neutropenia, and hypogammaglobulinemia. Early diagnosis is important for appropriate management and treatment.

References

2. Dotta L, Tassone L, Badolato R. Clinical and genetic features of Warts, Hypogammaglobulinemia, Infections and Myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome. Curr Mol Med. 2011;11(4):317-25.

3. Hernandez PA, Gorlin RJ, Lukens JN, Taniuchi S, Bohinjec J, Francois F, et al. Mutations in the chemokine receptor gene CXCR4 are associated with WHIM syndrome, a combined immunodeficiency disease. Nat Genet. 2003;34(1):70-4.

4. Kawai T, Choi U, Whiting-Theobald NL, Linton GF, Brenner S, Sechler JM, et al. Enhanced function with decreased internalization of carboxy-terminus truncated CXCR4 responsible for WHIM syndrome. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(4):460-8.

5. Luo J, De Pascali F, Richmond GW, Khojah AM, Benovic JL. Characterization of a new WHIM syndrome mutant reveals mechanistic differences in regulation of the chemokine receptor CXCR4. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(2):101551.

6. Aprikyan AA, Liles WC, Park JR, Jonas M, Chi EY, Dale DC. Myelokathexis, a congenital disorder of severe neutropenia characterized by accelerated apoptosis and defective expression of bcl-x in neutrophil precursors. Blood. 2000;95(1):320-7.

7. Mc Guire PJ, Cunningham-Rundles C, Ochs H, Diaz GA. Oligoclonality, impaired class switch and B-cell memory responses in WHIM syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2010;135(3):412-21.

8. Ellison M, Salzer U, Geier C, Ong M-S, Cruz R, Gordon S, et al., editors. Immune cell profiling and fitness in WHIM syndrome. New York: Springer/Plenum Publishers; 2021.

9. Keszei M, Devonshire AL, Ellison M, Csomos K, Ujhazi B, Makhija M, et al., editors. Abnormal B Cell Function in WHIM Syndrome. New York: Springer/Plenum Publishers; 2019.

10. Tiri A, Masetti R, Conti F, Tignanelli A, Turrini E, Bertolini P, et al. Inborn Errors of Immunity and Cancer. Biology (Basel). 2021;10(4).

11. Geier CB, Ellison M, Cruz R, Pawar S, Leiss-Piller A, Zmajkovicova K, et al. Disease Progression of WHIM Syndrome in an International Cohort of 66 Pediatric and Adult Patients. J Clin Immunol. 2022;42(8):1748-65.

12. Evans MO, 2nd, Petersen MM, Khojah A, Jyonouchi SC, Edwardson GS, Khan YW, et al. TREC Screening for WHIM Syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(3):621-8.

13. Badolato R, Dotta L, Tassone L, Amendola G, Porta F, Locatelli F, et al. Tetralogy of fallot is an uncommon manifestation of warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2012;161(4):763-5.

14. Nagasawa T, Nakajima T, Tachibana K, Iizasa H, Bleul CC, Yoshie O, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a murine pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor/stromal cell-derived factor 1 receptor, a murine homolog of the human immunodeficiency virus 1 entry coreceptor fusin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93(25):14726-9.

15. Zou YR, Kottmann AH, Kuroda M, Taniuchi I, Littman DR. Function of the chemokine receptor CXCR4 in haematopoiesis and in cerebellar development. Nature. 1998;393(6685):595-9.

16. Lagane B, Chow KYC, Balabanian K, Levoye A, Harriague J, Planchenault T, et al. CXCR4 dimerization and β-arrestin–mediated signaling account for the enhanced chemotaxis to CXCL12 in WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2008;112(1):34-44.

17. Balabanian K, Lagane B, Pablos JL, Laurent L, Planchenault T, Verola O, et al. WHIM syndromes with different genetic anomalies are accounted for by impaired CXCR4 desensitization to CXCL12. Blood. 2005;105(6):2449-57.

18. Beaussant Cohen S, Fenneteau O, Plouvier E, Rohrlich PS, Daltroff G, Plantier I, et al. Description and outcome of a cohort of 8 patients with WHIM syndrome from the French Severe Chronic Neutropenia Registry. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:71.

19. Tassone L, Notarangelo LD, Bonomi V, Savoldi G, Sensi A, Soresina A, et al. Clinical and genetic diagnosis of warts, hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, and myelokathexis syndrome in 10 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123(5):1170-3, 3 e1-3.

20. Gulino AV, Moratto D, Sozzani S, Cavadini P, Otero K, Tassone L, et al. Altered leukocyte response to CXCL12 in patients with warts hypogammaglobulinemia, infections, myelokathexis (WHIM) syndrome. Blood. 2004;104(2):444-52.

21. Grange LJ, Reynolds JJ, Ullah F, Isidor B, Shearer RF, Latypova X, et al. Pathogenic variants in SLF2 and SMC5 cause segmented chromosomes and mosaic variegated hyperploidy. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):6664.

22. Boztug K, Appaswamy G, Ashikov A, Schaffer AA, Salzer U, Diestelhorst J, et al. A syndrome with congenital neutropenia and mutations in G6PC3. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(1):32-43.

23. Abdollahpour H, Appaswamy G, Kotlarz D, Diestelhorst J, Beier R, Schaffer AA, et al. The phenotype of human STK4 deficiency. Blood. 2012;119(15):3450-7.

24. Kudlaty E, Agnihotri N, Khojah A. Hypogammaglobulinaemia and B cell lymphopaenia in Barth syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2022;15(6).

25. Dale DC, Firkin F, Bolyard AA, Kelley M, Makaryan V, Gorelick KJ, et al. Results of a phase 2 trial of an oral CXCR4 antagonist, mavorixafor, for treatment of WHIM syndrome. Blood. 2020;136(26):2994-3003.

26. McDermott DH, Liu Q, Velez D, Lopez L, Anaya-O'Brien S, Ulrick J, et al. A phase 1 clinical trial of long-term, low-dose treatment of WHIM syndrome with the CXCR4 antagonist plerixafor. Blood. 2014;123(15):2308-16.

27. Furutani E, Newburger PE, Shimamura A. Neutropenia in the age of genetic testing: Advances and challenges. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(3):384-93.

28. Garabedian C, Neri L, Seng J, Jones GK, Woodring J. Application of an Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning Model for Estimating Potential US Prevalence of WHIM Syndrome, a Rare Immunodeficiency, from Insurance Claims Data. Blood. 2021 Nov 23;138:4305.

29. Bedair R, Iriart X. EDUCATIONAL SERIES IN CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE: Tetralogy of Fallot: diagnosis to long-term follow-up. Echo Research and Practice. 2019 Mar;6(1):R9.