Abstract

Background: The use of left placket single muscle flap covered anastomosis in proximal gastrectomy has not been reported in the literature. The occurrence of gastroesophageal reflux after proximal gastrectomy is closely related to the mode of digestive tract reconstruction. The currently available digestive tract reconstruction approach affects patient’s postoperative quality of life due to the disadvantages of gastroesophageal reflux and anastomotic stenosis. Therefore, the use of left open flap single muscle flap covered anastomosis in proximal gastrectomy may improve the postoperative quality of life of patients. We present a case report and literature review to illustrate the therapeutic results of left-opening single muscle flap covered anastomosis in proximal gastrectomy.

Case presentation: Two male patients with average age of 70.5 years and average BMI of 20.5 underwent laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with an intraoperative left open flap single muscle flap covered overlap anastomosis. The average duration of surgery was 277.5 min, with average intraoperative bleeding of 100 ml, and no anastomotic stenosis was detected by contrast examination on the sixth postoperative day. The postoperative exhaust time was 3 days in both cases, liquid diet was given for 7 days and discharged from the hospital on the 8th day after operation. On an average 19 lymph nodes were dissected. The postoperative pathological stages were T3N2M0 and T1bN0M0. No gastroesophageal reflux or anastomotic fistula was detected in the recent follow-up.

Conclusion: The application of the left flap covering the overlap anastomosis in laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy has achieved good results. Multi center large sample clinical studies are needed to further determine its role in gastroesophageal reflux.

Keywords

Laparoscopy, Proximal gastrectomy, Single muscle flap, Stomach tumors, Gastroesophageal reflux

Introduction

In 2020, the global incidence of gastric cancer ranked fifth among malignant tumors and fourth in mortality from cancer. The incidence of gastric cancer in East Asia is the highest in the world, in China the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer are the third and second among malignant tumors, respectively [1,2]. In recent years, the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased globally, but the proportion of esophagogastric junction cancer and gastric cancer in the upper third ranges from 9% to 25% and is on the rise [3-5]. According to a case registry study at West China Hospital of Sichuan University, the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in gastric adenocarcinoma increased from 22.3% to 35.7% over 25 years [6].

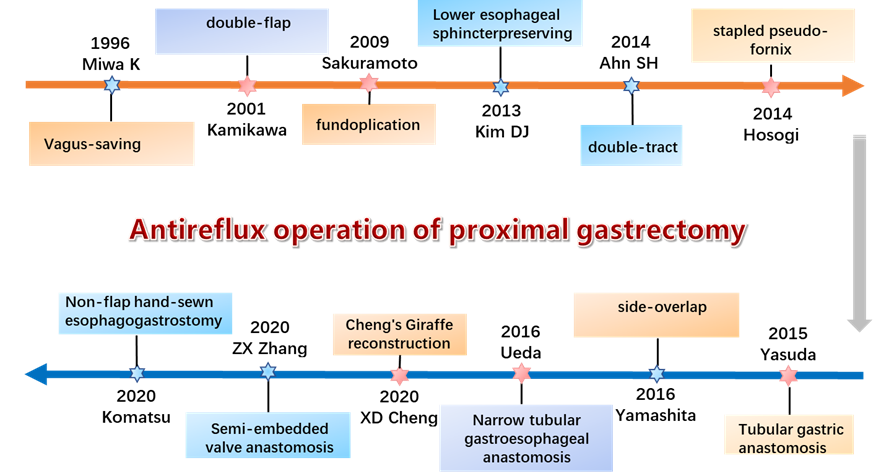

All tumors of the esophagogastric junction with the center of the tumor within 5 cm from the dentate line of the esophagus belong to the Siewert type, among which Siewert I is 1-5 cm above the dentate line, Siewert II is 1 cm above the dentate line to 2 cm below, and Siewert III is 2-5 cm below the dentate line. The method used for resection of Siewert II tumors is controversial, and there is no clinical consensus at present. Proximal gastrectomy is widely used in Asian countries because of its advantages in nutrient absorption and preservation of the physiological functions of the stomach [7]. However, proximal gastrectomy disrupts the angle of His and removes the lower esophageal sphincter, resulting in the loss of the antireflux barrier and a postoperative gastroesophageal reflux incidence of 4.5% to 28.6% [8]. Researchers have been exploring antireflux procedures for reconstruction of the digestive tract after proximal gastrectomy. For example, the Vagus-saving method proposed by Miwa et al. in 1996 [9], the double muscle flap anastomosis proposed by Kamikawa et al. in 2001, and the flapless manual anastomosis proposed by Komatsu et al. in 2020 [10]. The development of reconstruction methods is shown in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1:Development of antireflux operation in proximal gastrectomy.

|

Years |

Author |

Anti reflux operation |

Sample size |

Patient characteristics |

Gastroesophageal reflux (%) |

Anastomotic stenosis (%) |

Anastomotic leakage (%) |

Operation time(min) |

Reference |

|

2013 |

Dong Jin Kim |

Lower esophageal sphincter-preserving |

9 |

average age 60.7, male 6, female 3 |

0.00 |

11.11 |

11.11 |

143.56 |

[11] |

|

2013 |

Isao Nozaki |

Jejunal interposition |

102 |

average age 67, male 79, female 23 |

3.00 |

5.88 |

0 |

- |

[12] |

|

2014 |

Masaki Nakamura |

Fundoplication |

64 |

average age 73, male 49, female 15 |

22.00 |

18.75 |

0 |

- |

[13] |

|

Jejunal interposition |

25 |

average age 70, male 21, female 4 |

0.00 |

28.00 |

0 |

- |

|||

|

Jejunal pouch interposition |

12 |

average age 50, male 9, female 3 |

8.00 |

8.33 |

0 |

- |

|||

|

2014 |

Hisahiro Hosogi |

Stapled pseudo-fornix |

15 |

average age 69.7, male 13, female 2 |

26.70 |

20.00 |

6.67 |

315 |

[14] |

|

2015 |

Atsushi Yasuda |

A reliable angle of His by placing a gastric tube |

25 |

average age 71.6, male 18, female 7 |

4.00 |

20.00 |

0 |

286.4 |

[15] |

|

Jejunal interposition |

21 |

average age 61, male 13, female 8 |

4.76 |

9.52 |

9.52 |

268.8 |

|||

|

2016 |

Shinji Kuroda, |

Double-Flap Technique |

33 |

median age 73, male 26, female 7 |

0 |

9.09 |

0 |

319.5, 109* |

[16] |

|

2017 |

Yoshito Yamashita |

Side overlap esophagogastrostomy |

14 |

average age 59, male 11, female 3 |

7.14 |

0.00 |

0 |

330, 38* |

[17] |

|

Non-Side overlap esophagogastrostomy |

16 |

average age 66, male 11, female 5 |

31.25 |

18.75 |

12.50 |

337, 40* |

|||

|

2019 |

Kei Hosoda |

Double-flap |

40 |

average age 69.5, male 36, female 4 |

17.50 |

17.50 |

2.50 |

353 |

[18] |

|

OrVil techniques |

51 |

average age 69.7, male 38, female 13 |

49.00 |

27.45 |

7.84 |

280 |

|||

|

2019 |

Zhiguo Li |

PJIRSTR |

98 |

≤ 60 25, ≥ 60 73 male 88, female 10 |

3.06 |

0.00 |

0 |

144.37, 53.85* |

[19] |

|

PJIRDTR |

103 |

≤ 60 23, ≥ 60 80 male 90, female 13 |

2.91 |

0.00 |

0.97 |

143.62, 50.22* |

|||

|

2020 |

Baohua Wang |

Semi-embedded valve anastomosis |

28 |

average age 58.9, male 24, female 4 |

3.50 |

3.57 |

0 |

164.3, 35.4* |

[20] |

|

2020 |

Shuhei Komatsu |

Non-flap hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy |

23 |

average age 67, male 18, female 5 |

0.00 |

4.35 |

0 |

325 |

[10] |

|

2021 |

Ke-kang Sun |

Esophagus two-step-cut overlap |

48 |

average age 67, male 34, female 14 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

2.08 |

22.5* |

[21] |

|

2021 |

Takeshi Omori1 |

Tri Double-Flap Hybrid Method |

59 |

average age 68, male 12, female 47 |

6.78 |

5.08 |

1.69 |

316# |

[22] |

Currently, there are three main types of digestive tract reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy: an operation to change the morphology of the physiological digestive tract (tube anastomosis with pseudofornix, jejunal interposition, double-tract, tubular gastric anastomosis); modified esophagogastric anastomosis (side-overlap, semiembedded valve anastomosis, double-flap, non-flap hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy); and gastric function-preserving surgery (proximal gastrectomy with vagus-saving, proximal gastrectomy with lower esophageal sphincter-preserving). Although there are numerous proximal gastrectomy antireflux gastrointestinal reconstruction procedures, there is no uniform standard. In 2019, a multicenter retrospective study [23] showed that gastroesophageal reflux occurred in 10.6% of patients who underwent double muscle flap anastomosis, and the overall incidence of anastomosis-related complications was 7.2%.

Laparoscopic reconstruction is the only independent risk factor for anastomosis-related complications. This is mainly due to the drawbacks of the complex operation of double muscle flap anastomosis, the long learning time, the long operative time and the tendency of the double muscle flap to cause ischemic necrosis. Recently, our center has modified the laparoscopic reconstruction of the digestive tract after proximal gastrectomy by replacing the double muscle flap with a single muscle flap.

Case Presentation

Two male patients with average age of 70.5 years and average BMI of 20.5 underwent laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy with an intraoperative left open flap single muscle flap covered overlap anastomosis. One case with a moderately-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of T3N2M0 and another case with a moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma of T1bN0M0 (Table 2).

|

Case |

Years |

BMI |

TNM |

Operation time (min? |

Blood loss ?ml? |

Differentiation grade |

Tumor size ?cm? |

Number of lymph nodes dissected |

Hospitalization days |

Exhaust time ?day? |

|

1 |

75 |

20 |

T3N2M0 |

275 |

100 |

moderately-poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma |

5*4 |

17 |

8 |

3 |

|

2 |

66 |

21 |

T1bN0M0 |

280 |

100 |

moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma |

5*4 |

21 |

9 |

3 |

Operation method

The patient was placed under general anesthesia in the supine position with their legs spread apart, and laparoscopic instruments were inserted using the conventional "curved 5-hole method". After entering the abdomen, routine exploration was performed to determine whether there were metastatic lesions. D2 lymph node dissection for proximal gastric cancer was completed according to the Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) Clinical Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Gastric Cancer [24].

(1) Establish the pneumoperitoneum, an incision of approximately 1 cm is made in the lower part of the proposed esophageal resection and a stapler nail holder with a needle of 25 mm is inserted (Figure 2a). (2) The needle was punctured out of the esophageal wall at a position 2 cm to the upper right of the esophageal incision. (3) Using a 60 mm Endostapler transection, the esophagus is cut approximately 1 cm above the esophageal incision (Figure 2b). (4) Remove the nail holder and sutures of approximately 5 cm are reserved for traction, the pneumoperitoneum is closed, and the specimen is removed through the subumbilical incision to make a tubular stomach on the premise that the tumor resection margin is guaranteed. The tumor is located in the gastric fundus posterior wall near the cardia, without invasion of the serosal layer. A rightward “?” shape with a width of 3 cm and a vertical spacing of 4 cm is marked approximately 3-4 cm from the proximal end of the residual anterior gastric wall (Figure 2c). (5) Cut according to the marked "?" shape to form a single muscle valve (Figure 2d). (6) The muscle flap is used to wrap the anastomosis in the subsequent process (Figure 2e). An opening of about 2 cm is opened longitudinally at approximately 4 cm below the muscle flap, and then a 25 mm circular stapler is inserted through the opening and passed out at the center of the “?” shape to from the muscle flap. (7) The remnant stomach is placed back into the abdominal cavity, the pneumoperitoneum is established again, and esophageal stump anastomosis. Covering the anastomosis with a single muscle flap, continuously strengthening the suture with 3 #0 barbed wire and wrapping the “?” continuous suture on the pulp muscle flap of the anterior wall of the stomach around the anastomosis, (Figures 2f-2h). (8) The posterior wall of the broken end of the esophagus was overlapped with the mucosa and submucosa of the remnant stomach. The anterior wall of the broken end of the esophagus was continuously sutured with the whole layer of the remnant stomach. The plasma muscle flap of the anterior wall of the stomach was sutured and embedded in the anastomosis to complete the reconstruction of the digestive tract (Figure 2i).

Figure 2: Laparoscopic Proximal Gastrectomy Esophagogastric Kamikawa Anastomosis Modification Procedure. a. an incision of about 1 cm was made at 2 cm in the lower part of the proposed esophageal resection, and a stapler nail holder with a needle of 25 mm was inserted; b. The 60 mm Endostapler transection of the esophagus about 1 cm above the esophageal incision; c. 3-4 cm away from the proximal end of the anterior wall of the remnant stomach is marked with a “?” shape, the width is about 3 cm, the upper and lower spacing is about 4 cm; d. The electric scalpels incised the plasma membrane and muscle layer on the upper and lower sides of the “?” shaped transverse row and the right side of the longitudinal row, preserving the left plasma membrane and forming a single muscle flap; e. Single muscle flap overlying the anastomosis; f. continuous reinforcement of the anastomosis with barbed sutures; g. posterior wall anastomosis with continuous suturing of the entire esophageal section and the mucosal and submucosal layers of the remnant stomach; h. continuous suturing of the antral pulpy muscle flap in a “?” shape around the anastomosis; i.formation of an Overlap single muscle flap.

The number of lymph node dissections and tumor pathological staging was done according to the 2017 American Joint Commission on Cancer TNM staging standard (8th Edition) [25].

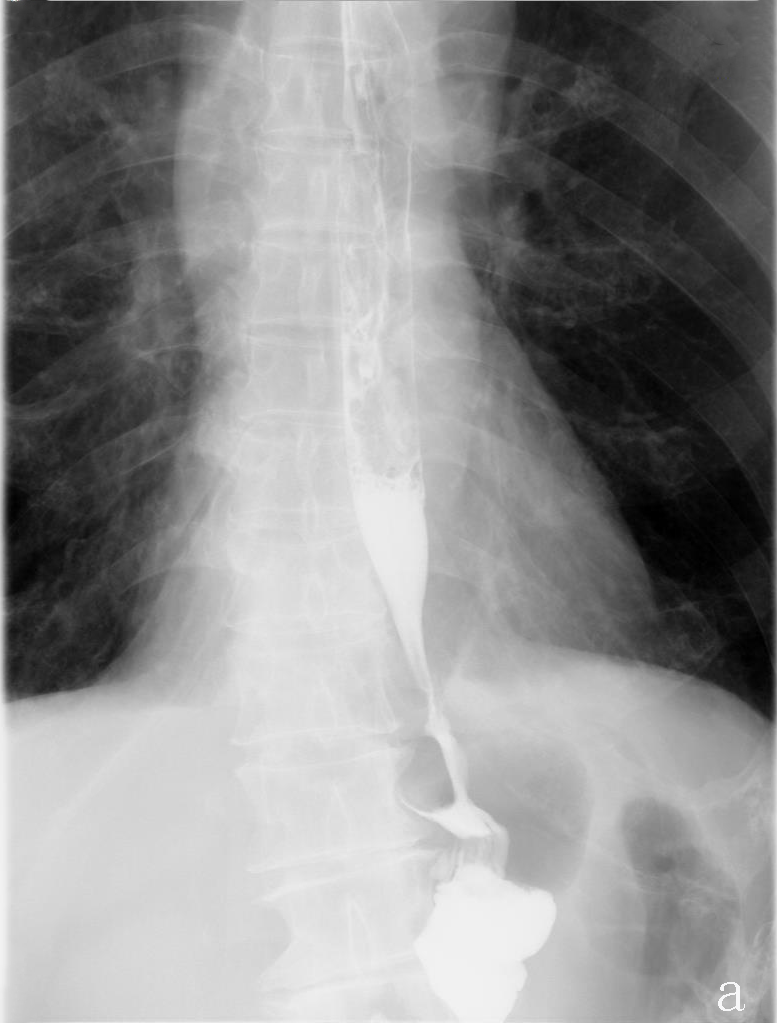

The average duration of surgery was 277.5 min and average intraoperation blood loss was 100 ml. The postoperative exhaust time was 3 days in both cases. Upper digestive tract water-soluble angiography was performed on the 6th postoperative day to rule out anastomotic leakage and anastomotic stenosis (Figure 3), oral feeding was resumed, and the nutrient tube was removed. Liquid diet was followed for 7 days and patients were discharged from the hospital on the 8th day after operation. Average of 19 lymph nodes were dissected.

Figure 3:Upper digestive tract water-soluble angiography.

Discussion and Conclusion

The destruction of the antireflux barrier due to the removal of the cardia by proximal gastrectomy leads to a higher incidence of anastomotic stricture and reflux esophagitis [26,27]. Therefore, the mode of reconstruction of the digestive tract after proximal gastrectomy is particularly important. Miwa et al. were the first to propose a proximal gastrectomy with preservation of the vagus nerve, but with the proposed function of gastric preservation, the anatomical structure has become more demanding, requiring dissection of the hepatobiliary and abdominal branches. This surgical procedure is more complex and robotic surgery offers significant advantages [9]. Kim et al. reported a lower esophageal sphincter-preserving procedure with one postoperative anastomotic fistula (11.11%) and one anastomotic stricture (11.11%) without gastroesophageal reflux. This procedure was limited to gastric cancer located in corpus and fundus with a small curved side <3 cm and a large curved side <5 cm due to the need to preserve the lower esophageal sphincter [11].

Hosogi et al. [14] reported a sutured pseudodome procedure in which the linear anastomosis was cut with scissors to drain the staples, the anterior esophageal wall was sutured vertically and intermittently to the remnant stomach, a pseudodome was made manually, and 26.7% of patients developed gastroesophageal reflux at the one-year postoperative endoscopic follow-up.

Nozaki et al. [12] reported 95 cases of proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition placement, which showed only 3 cases of gastroesophageal reflux (3%) (GERD B). Dual-channel anastomosis, a modification of the jejunal interposition, is the more popular procedure recommended in recent years. Li et al. performed an RCT study of dual-channel anastomosis, jejunal interposition, and Roux-en-Y anastomosis [19]. The incidence of gastroesophageal reflux at 18 months postoperatively was 20.2% in the Roux-en-Y anastomosis group and only 2.9% and 3.1% in the dual-channel anastomosis and jejunal interposition groups. Jejunal interposition is more irritating to the remnant gastric sinus and increases gastric acid secretion, which increases the risk of peptic ulcer. Compared to jejunal interposition, dual-channel anastomosis allows direct jejunal access to still pass food when abnormal residual gastroduodenal access occurs, and direct jejunal access reduces the stimulation of the residual gastric sinus and decreases gastric acid secretion. However, due to the numerous anastomoses of dual-channel anastomosis, it increases the risk of anastomotic stenosis and anastomotic fistula and requires a higher level of laparoscopic manipulation by the operator.

In 2015, Yasuda et al. [15]. reported a tubular gastric anastomosis, which is mainly a linear cutting-closure device that closes the gastric tissue along the side of the lesser curvature parallel to the greater curvature of the stomach, forming a tubular stomach 5-7 cm wide and approximately 20 cm long. Follow-up results showed that only 1 patient out of 25 patients developed gastroesophageal reflux (4%). However, this surgery increases the risk of bleeding and leakage due to the presence of a long gastric wall incision margin in the tubular stomach, which predisposes patients to esophagogastric anastomotic stricture.

In 2017, Yamashita et al. [17]. reported a side overlap esophagogastrostomy, where the left angle of the esophageal dissection was opened by ultrasonic shears, and the width was able to permit a linear cutter stapler to fix the leftmost and rightmost ends of the remnant stomach to the right and left diaphragm feet; the anterior wall of the remnant stomach was opened, the sidewall of the esophageal remnant stomach was anastomosed, and the closure was rotated counterclockwise at an angle. It was found that in the side-overlap anastomosis group, 7% of patients developed reflux esophagitis, while 31% of patients in the conventional esophageal remnant gastric anastomosis group developed reflux esophagitis. However, this surgery is not suitable for patients with a high tumor location.

In 2020, a semi-embedded valve anastomosis was reported by Zhang et al. [20]. The left half of the esophagus is deeply encapsulated by a circular anastomosis using a linear cutter stapler with a row of staples to form a one-way flap to reconstruct the angle of His and fundus. Gastroscopy was repeated six months after surgery in 28 patients and only 1 patient was found to have gastroesophageal reflux (3.6%, GERD B). This procedure may cause anastomotic stricture due to excessive encapsulation, and its cost is high.

In 2001, Kamikawa et al. reported a double muscle flap anastomosis to achieve antireflux by increasing the pressure at the ventral segment esophageal and remnant gastric junction, after which a study reported by Kuroda et al. [16] in 2016 showed that 33 patients who underwent proximal gastrectomy followed by double muscle flap anastomosis had no esophagogastric reflux (GERD ≥ B) one year after either open or laparoscopic double muscle flap anastomosis. However, three patients (9%) developed anastomotic stenosis requiring balloon dilation. This study demonstrated for the first time the feasibility of the Kamikawa double muscle flap procedure performed laparoscopically.

In 2020, Komatsu et al. [10] reported a flapless hand-sutured anastomosis, and Komatsu et al. suggested that the anti-reflux was not caused by the double flap covering but rather by the reconstructed stapled pseudofornix, with a flattened anastomosis closed by pressure. The first few steps of its anastomosis operation were the same as the double muscle flap anastomosis, followed by freeing the abdominal segment of the esophagus for 5 cm and overlapping the anastomosis with the remnant stomach, fixing the uppermost part of the remnant stomach with a bilateral diaphragm foot suture, and the anastomosis was achieved by hand suture. Twenty-three patients were followed up for six months and none had gastroesophageal reflux (GERD ≥ B).

Double muscle flap anastomosis and flapless manual anastomosis using anterior esophagogastric wall anastomosis, which does not modify the digestive tract, have less impact on gastrointestinal hormones and do not affect gastroscopic examinations. However, the operation is complicated, the technical requirements are high, the double flap coverage can be too tight and may cause anastomotic stenosis, the poor blood flow of the muscle flap may cause necrosis, and the high requirements for the remaining remnant of the stomach [28].

To address these shortcomings of double muscle flap surgery, our team changed the double muscle flap to a single muscle flap based on the Kamikawa surgery and used it in our practice. The use of barbed wire in the closure of the single muscle flap tunneled structure avoids overtightening that can lead to anastomotic stenosis, and it provides an antireflux effect. We performed a small incision below the umbilicus for reverse puncture anastomosis to reduce the risk of reflux by encasing the anastomosis with a single muscle flap based on the tubular stomach. This technique can avoid the shortcomings of traditional tubular gastroesophageal anastomosis, such as a longer incision, difficult exposure, and a high risk of anastomosis stenosis.

In practice, we have found that a single muscle flap is easier and safer to make on a tubular stomach, the anastomotic embedding is also more complete, and the reverse puncture anastomosis with the incision below the umbilicus has a better view for patients with higher tumors. No anastomotic stenosis was found on the sixth day after operation. No adverse symptoms were observed based on the latest follow-up results. This preliminary result indicated that the short-term effectiveness of laparoscopic single muscle flap formation after proximal gastrectomy reached the expected results.

Further examination and longer follow-up are needed to determine the long-term efficacy of this technique. Future prospective, multicenter, large-sample prospective studies are needed to verify whether this technique can be used as one of the options for postproximal gastrectomy digestive tract reconstruction.

References

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2021 May;71(3):209-49.

3. Leers JM, Knepper L, van der Veen A, Schröder W, Fuchs H, Schiller P, et al. The CARDIA-trial protocol: a multinational, prospective, randomized, clinical trial comparing transthoracic esophagectomy with transhiatal extended gastrectomy in adenocarcinoma of the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) type II. BMC Cancer. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-2.

4. Jung MK, Schmidt T, Chon SH, Chevallay M, Berlth F, Akiyama J, et al. Current surgical treatment standards for esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancer. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2020 Dec;1482(1):77-84.

5. Ishikawa S, Shimada S, Miyanari N, Hirota M, Takamori H, Baba H. Pattern of lymph node involvement in proximal gastric cancer. World Journal of Surgery. 2009 Aug;33(8):1687-92.

6. Liu K, Yang K, Zhang W, Chen X, Chen X, Zhang B, et al. Changes of esophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma and gastroesophageal reflux disease among surgical patients during 1988–2012: a single-institution, high-volume experience in China. Annals of Surgery. 2016 Jan;263(1):88.

7. Kumamoto T, Sasako M, Ishida Y, Kurahashi Y, Shinohara H. Clinical outcomes of proximal gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A comparison between the double-flap technique and jejunal interposition. Plos One. 2021 Feb 24;16(2):e0247636.

8. Wang S, Lin S, Wang H, Yang J, Yu P, Zhao Q, et al. Reconstruction methods after radical proximal gastrectomy: a systematic review. Medicine. 2018 Mar;97(11).

9. Miwa K, Kinami S, Sato T, Fujimura T, Miyazaki I. Vagus-saving D2 procedure for early gastric carcinoma. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 1996 Apr 1;97(4):286-90.

10. Komatsu S, Kosuga T, Kubota T, Kumano T, Okamoto K, Ichikawa D, et al. Non-flap hand-sewn esophagogastrostomy as a simple anti-reflux procedure in laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy for gastric cancer. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2020 Jun;405(4):541-9.

11. Kim DJ, Lee JH, Kim W. Lower esophageal sphincter-preserving laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy in patients with early gastric cancer: a method for the prevention of reflux esophagitis. Gastric Cancer. 2013 Jul;16(3):440-4.

12. Nozaki I, Hato S, Kobatake T, Ohta K, Kubo Y, Kurita A. Long-term outcome after proximal gastrectomy with jejunal interposition for gastric cancer compared with total gastrectomy. World Journal of Surgery. 2013 Mar;37(3):558-64.

13. Nakamura M, Nakamori M, Ojima T, Katsuda M, Iida T, Hayata K, et al. Reconstruction after proximal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer in the upper third of the stomach: an analysis of our 13-year experience. Surgery. 2014 Jul 1;156(1):57-63.

14. Hosogi H, Yoshimura F, Yamaura T, Satoh S, Uyama I, Kanaya S. Esophagogastric tube reconstruction with stapled pseudo-fornix in laparoscopic proximal gastrectomy: a novel technique proposed for Siewert type II tumors. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2014 Apr;399(4):517-23.

15. Yasuda A, Yasuda T, Imamoto H, Kato H, Nishiki K, Iwama M, et al. A newly modified esophagogastrostomy with a reliable angle of His by placing a gastric tube in the lower mediastinum in laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2015 Oct;18(4):850-8.

16. Kuroda S, Nishizaki M, Kikuchi S, Noma K, Tanabe S, Kagawa S, et al. Double-flap technique as an antireflux procedure in esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 2016 Aug 1;223(2):e7-13.

17. Yamashita Y, Yamamoto A, Tamamori Y, Yoshii M, Nishiguchi Y. Side overlap esophagogastrostomy to prevent reflux after proximal gastrectomy. Gastric Cancer. 2017 Jul;20(4):728-35.

18. Hosoda K, Washio M, Mieno H, Moriya H, Ema A, Ushiku H, et al. Comparison of double-flap and OrVil techniques of laparoscopy-assisted proximal gastrectomy in preventing gastroesophageal reflux: a retrospective cohort study. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2019 Feb;404(1):81-91.

19. Li Z, Dong J, Huang Q, Zhang W, Tao K. Comparison of three digestive tract reconstruction methods for the treatment of Siewert II and III adenocarcinoma of esophagogastric junction: a prospective, randomized controlled study. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2019 Dec;17(1):1-9.

20. Wang B, Wu Y, Wang H, Zhang H, Wang L, Zhang Z. Semi-embedded valve anastomosis a new anti-reflux anastomotic method after proximal gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction. BMC Surgery. 2020 Dec;20(1):1-9.

21. Sun KK, Wang Z, Peng W, Cheng M, Huang YK, Yang JB, et al. Esophagus two-step-cut overlap method in esophagojejunostomy after laparoscopic gastrectomy. Langenbeck's Archives of Surgery. 2021 Mar;406(2):497-502.

22. Omori T, Yamamoto K, Yanagimoto Y, Shinno N, Sugimura K, Takahashi H, et al. A Novel Valvuloplastic Esophagogastrostomy Technique for Laparoscopic Transhiatal Lower Esophagectomy and Proximal Gastrectomy for Siewert Type II Esophagogastric Junction Carcinoma—the Tri Double-Flap Hybrid Method. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 2021 Jan;25(1):16-27.

23. Kuroda S, Choda Y, Otsuka S, Ueyama S, Tanaka N, Muraoka A, et al. Multicenter retrospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the double?flap technique as antireflux esophagogastrostomy after proximal gastrectomy (rD?FLAP Study). Annals of Gastroenterological Surgery. 2019 Jan;3(1):96-103.

24. Wang FH, Shen L, Li J, Zhou ZW, Liang H, Zhang XT, et al. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer. Cancer Communications. 2019 Dec;39(1):1-31.

25. Amin MB, Greene FL, Edge SB, Compton CC, Gershenwald JE, Brookland RK, et al. The eighth edition AJCC cancer staging manual: continuing to build a bridge from a population‐based to a more “personalized” approach to cancer staging. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2017 Mar;67(2):93-9.

26. Ji X, Jin C, Ji K, Zhang J, Wu X, Jia Z, et al. Double tract reconstruction reduces reflux esophagitis and improves quality of life after radical proximal gastrectomy for patients with upper gastric or esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research and Treatment: Official Journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2021 Jul 1;53(3):784-94.

27. Hojo Y, Nakamura T, Kumamoto T, Kurahashi Y, Ishida Y, Kitayama Y, et al. Marked improvement of severe reflux esophagitis following proximal gastrectomy with esophagogastrostomy by the right gastroepiploic vessels-preserving antrectomy and Roux-en-Y biliary diversion. Gastric Cancer. 2022 Jul 7:1-6.

28. Mine S, Nunobe S, Watanabe M. A novel technique of anti-reflux esophagogastrostomy following left thoracoabdominal esophagectomy for carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. World Journal of Surgery. 2015 Sep;39(9):2359-61.