Abstract

Frankincense oil is widely used across the globe for various therapeutic implications. However, the potential toxicity profile of Frankincense oil has not been well explored. The present study is a debut attempt to study the organ-specific (cardiac, hepatic, and neuromuscular) toxicity profile of Frankincense essential oil from Boswellia sacra using the zebrafish embryo model. The results revealed a “no observed effect concentration” (NOEC) dose of Frankincense oil of 300 µg/ml. Signs of cardiac toxicity were not observed if the zebrafish embryos were incubated with Frankincense oil (100 µg/ml). In addition, signs of genotoxicity were also not observed at the same concentration. Similarly, neuromuscular toxicity evaluated by the locomotor activity in the presence of light and hepatic toxicity measured by liver size, yolk retention, and steatosis were not found. Despite the absence of toxic effects of Frankincense oil on zebrafish embryo survival, it should be further investigated to assess if the prolonged administration of Frankincense oil in higher vertebrates might induce potential toxic effects.

Keywords

Frankincense oil, Zebrafish, Acute toxicity, Genetic toxicity, Systemic toxicity

Introduction

Frankincense, commonly called “olibanum”, is a gum resin exudate from the Boswellia genus, which is widely found in the tropical regions of Asia and Africa [1]. Boswellia species are rich in the phytochemical constituent terpenoids, and almost 200 constituents have been reported so far [2]. Boswellia resin contains 5-9% essential oils, 21-22% water, and 65-85% alcohol soluble resin [3]. Frankincense exudate has been used in the traditional medical systems of China, Rome, Arabian countries, India, Greece, etc. for ages. It is used for conditions such as blood stagnation, inflammation, swelling, and pain [4]. The major bioactive compounds present in the exudate are α-pinene (45%), α-thujene (12%), sabinene (2.2%), methylchavicol (11.6%), kessane (0.9%), limonene (1.9%), 4-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKβ-BA) to 11-keto-β-boswellic acid (Kβ-BA), and linalool (0.9%). In addition, it also contains monoterpene and diterpenoid compounds [5,6].

The acid fraction and the limonene fraction of Frankincense oil possess potent antibacterial activity, particularly against Bacillus species [7], and antifungal properties [8], respectively. Boswellic acid and its derivatives also showed anti-tumor activity. The methanolic extract of Frankincense oil showed anti-carcinogenic properties by inhibiting TH1 cytokines [9]. The triterpenoid acid from Frankincense demonstrated significant cytotoxic activity by inhibiting the phosphorylation of Erk-1/2 [10,11]. In addition, free radical scavenging and anti-inflammatory properties of Frankincense have also been well established [12,13].

There is a rising interest towards the phenotype-based drug screening in drug discovery research. Screening of test compounds in zebrafish provides unique advantages of screening in living animals. The screening is carried out in zebrafish larvae or adults since it exhibits similarity towards biological processes across the vertebrate organ systems. In addition, their large-scale embryo production and rapid development facilitate drug screening procedures. The zebrafish model provides an early insight into the toxicity of drug candidate molecules. Unlike cell-based assays which provide limited information on the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of test compounds, the zebrafish model is sensitive to toxicological and pharmacological characterization as they share approximately 70% similarity to human genes; further, 84% of the genes are associated with human diseases [14-16]. Moreover, earlier studies have confirmed the physiological similarity of the organs of the zebrafish with those of human beings [17-19]. Hence, zebrafish serves as an excellent model to investigate the potential toxicity and the mechanisms of action of candidate drugs.

The therapeutic properties of Frankincense oil are well established in vivo and in vitro. Numerous studies reported the safety of Boswellia extracts. However, contradictory reports are also available. For instance, Boswellia serrata at a dose of 1000 mg/kg showed toxicity in a 90-day safety assessment study wherein the “no observed adverse effect level” (NOEL) was 500 mg/kg [20]. Another study by Devi et al. reported a NOEL for Boswellia ovalifoliata of 500 mg/kg in rats [21]. The most popular and commonly used Frankincense is from Boswellia sacra. Yahya et al. reported in a 28-day oral toxicity study that Boswellia sacra showed no signs of behavioral and organ toxicity up to doses of 100 mg/kg [22]. In addition, Han et al. performed a developmental and cardiotoxicity study of acetyl-11-keto-b-boswellic acid (AKBA) in zebrafish and found that AKBA induced developmental and cardiotoxicities by decreasing the antioxidant enzymes in zebrafish embryos [23]. The present study was designed to establish the neuro-, cardio-, and hepatotoxicities as well as the genotoxic profile of Frankincense oil in the zebrafish model.

Materials and Methods

Frankincense oil preparation

Omani frankincense gum resin grade Najdi from Boswellia sacra was subjected to hydrodistillation for 2 h using Clevenger apparatus to chemoprofile the compounds present in the Najdi gum resin [24,25]. The oil was serially diluted in E3 medium (34.8 g NaCl, 1.6 g KCl, 5.8 g CaCl2 × 2 H2O, 9.78 g MgCl2 × 6 H2O made up to 2 l with H2O) to obtain 5 logarithmic concentrations, i.e., 1000 µg/ml, 300 µg/ml, 100 µg/ml, 30 µg/ml, and 10 µg/ml.

Extraction and characterization of Frankincense oil

Frankincense oil (FO) extract was prepared from Boswellia sacra via the hydrolyzation method using a Clevenger-type apparatus at the Biodiversity Lab, Dhofar University, Oman. Briefly, 250 g of finely powdered Frankincense oleogum resin was added into a round-bottom flask which contained 2500 ml of distilled water, and then fixed onto a heating mantle. The hydrolyzation process was performed in a steam jacket maintained at atmospheric pressure and temperature at 100°C. Subsequently, Grade 1 essential oil was obtained after 2 h of hydrolyzation. Grades 2 and 3 were obtained after 4 and 6 h of hydrolyzation, respectively. The collected essential oils were dried with anhydrous sodium sulfate, stored in dark glass bottles and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) [26].

Zebrafish embryo and husbandry

Wild-type zebrafish strain AB and transgenic green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing zebrafish strains were procured and acclimatized in the ZeClinics zebrafish facility, Barcelona, Spain. The room was maintained at 14 h light/10 h dark cycle and the water temperature was maintained at 28 ± 2°C. The tank water was partially changed every week, and the quality was regularly analyzed. The fish were fed twice a day with commercial fish food pellets (TetraMin™). The aquarium was equipped with a mesh at the bottom to avoid cannibalization.

Zebrafish embryo collection

Fertilized embryos of Danio rerio were transferred to Petri plates containing E3 medium. Abnormal and non-fertilized embryos were removed. At 3 h post fertilization (hpf), 20 healthy embryos as per condition were transferred into each well of 24-well plates with E3 medium. After placing the embryos, the E3 medium were replaced with fresh solutions containing different concentrations of desired drugs to be tested in various assays. In the present study, the authors followed the national and international guidelines to carry out the experiments in zebrafish in accordance with the guidelines required by ZeClinic.

Acute toxicity assays

The acute toxicity was performed by following The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) test guideline number 203 and 206 [24,25]. The E3 medium was replaced with prepared dilutions of FO, N,N-diethyl amino benzaldehyde (DEAB), and 1% DMSO which served as the test group, positive control, and negative control, respectively. The embryos were allowed at 96 hpf medial lethal dose (LC50). No observed effect concentration (NOEC), lowest observed effect concentration (LOEC), Number of coagulated eggs, formation of somite, tail detachment and presence of heartbeat were observed at 24, 48, and 96 hpf following test drug exposure. In addition, the teratogenicity potential was recorded in terms of body deformity, developmental delay, scoliosis, pigmentation, and heart edema at the pre-fixed time-points. In positive controls, the embryos were exposed to five different concentrations of DEAB, i.e., 0.1 μM, 1 μM, 10 μM, 100 μM, 1 mM in E3 medium.

Genotoxicity assay

Genotoxicity assay was performed according to the OECD test guideline 236. At 3 hpf, zebrafish embryos were incubated with E3 medium or Frankincense oil (300 μg/ml) for 96 h and mortality was checked every 24 h for 3 days. Following the test drug exposure, zebrafish embryos were anaesthetized with 0.17 mg/ml tricaine methane-sulfonate (MS-222) [27] and fixated with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C. After fixation, the embryos were washed twice in 1× PBST and incubated overnight in 30% sucrose/ 0.02% sodium azide/ 1× PBS solution. Embryos were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) blocks and cut into thin sections of size 14 µm. Before staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), the sections were rehydrated. Microscopic analysis was performed using SP5 confocal microscope. Each 100 nuclei were analyzed and micronuclei were counted.

Neuromuscular toxicity assays

To understand the effect of Frankincense oil on the zebrafish embryo’s nervous system, the authors assessed the locomotor activity in response to an external environmental stimulus. Fertilized transgenic zebrafish embryos (Cmlc2:GFP; fabp10:RFP; ela31:EGFP) were allowed to develop until four days post fertilization (dpf) at 28°C, which is the time when the fish acquire proper swimming activity. At 96 hpf, healthy larvae are transferred individually into a rounded 96-well plate (one embryo per well) with the aid of a pipette.

At 120 hpf, the embryos were incubated with Frankincense oil (300 μg/ml) and 5 mM pentylenetetrazole (PTZ) as positive control for 3 h. Following incubation, the CNS effects were analyzed using EthoVision XT 12 software and the DanioVision device from Noldus Information Technologies, Netherlands. The system was equipped with a camera placed above a chamber with circulating water and a temperature sensor programmed at 28.5°C. Each individual larva was kept in a 48-well plate and placed into the chamber. The chamber was then programmed to produce different stimuli such as light/dark environment, tapping and sound which were controlled by the software. Prior to each experiment, the larvae were acclimatized in the dark for 10 min. Then, the larvae were subjected to pre-programmed series of alternating dark - light environment and external stimuli. Briefly, the protocol contained 50 min of dark/light alternating environments phase (10 min each), then a series of five short flashes of light to detect epileptic seizures and finally a series repeated tapping for 30 sec (1 tapping/sec).

The first phase was designed to detect any anomalies in larval movement and stereotyped behavior. In addition, time spent by the larvae in the center or the periphery was used to measure their anxiety state. The second phase enabled us to analyze larval response to a seizure inducing visual stimuli and measure the putative seizure characteristics, i.e., the maximum velocity and the number of angles turned (specific of seizure erratic movement). The final phase detected alterations in short-term memory and learning. The above changes could be evaluated by testing the capacity to gradually reduce the response to the external stimuli, a process known as “habituation”. The CNS effects were assessed by comparing locomotory differences between the positive control and Frankincense oil-exposed larvae.

Cardiotoxicity assays

To analyze the cardiac effects of Frankincense oil-fertilized embryos of transgenic zebrafish (Cmlc2:GFP; fabp10:RFP; ela31:EGFP) were collected and allowed to develop until 5 dpfat 28.5°C, till the heartbeat became stable. At 96 hpf, zebrafish embryos were incubated with Frankincense oil (100 μg/ml), haloperidol (10 μM) and DMSO which served as test control, positive control, and negative control, respectively, for 4 h at 28.5°C. After the incubation period, the embryos were anaesthetized by immersion in 0.7 μM tricaine methane sulfonate/E3 solution.

Following incubation, the embryos were transferred into a microfluidic system (VAST, Union Biometrica, Belgium). The above system produces automatic aspiration, placement, and rotation of the larvae under the microscope (Leica, DM6-B, China). The embryos were positioned at the right angle, and the videos of fluorescent heart and blood flow were recorded for 30 sec. The recorded videos were analyzed using ZeCardio® software for the following parameters: bradycardia and tachycardia, QTc corrected interval according to the Framingham formula: QTc = QT + 0.154 (1 – RR), arrhythmia, atrial and ventricular fibrillation, cardiac arrest, and atrial and ventricular blood flow.

Hepatotoxicity assays

The hepatotoxic assay was carried out using the fertilized embryos of transgenic zebrafish (Cmlc2:GFP; fabp10:RFP; ela31:EGFP). The embryos were collected and allowed to develop until 5.5 days post fertilization at 28.5°C to reach full development of liver. To examine the hepatotoxicity of Frankincense oil, the authors analyzed the liver size, necrosis, yolk retention, hepatomegaly, and steatosis. At 96 hpf, zebrafish embryos were incubated with the following treatments: 1) Frankincense oil (300 μg/ml), 2) positive control acetaminophen (APAP) (2640 µM for necrosis and 1320 µM for yolk retention), 2% ethanol for steatosis, 3) negative control- DMSO. Following 32 h of incubation, the embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 2 – 4 h at room temperature and subjected to three washes with PBS. The following parameters were assessed for hepatotoxicity evaluation.

Following paraformaldehyde fixation, larvae were observed under a fluorescence stereo microscope (Olympus MVX10, Japan, and the images were captured with a digital camera (Olympus DP71) cell’D software. Hepatomegaly and necrosis assessment were performed using Fuji software (FugiFilm Holding Corporation, UK) Steatosis and yolk retention were evaluated by oil-red staining. Fixed larvae were bleached with bleach solution (0.1 ml of 5% sodium hypochlorite) for 20 min, followed by five washes with PBS. Prior to staining, bleached embryos were incubated in 85% propylene glycol (PG) for 10 min and then in 100% PG for 10 min. Thereafter, the embryos were incubated in Oil Red O 0.5% in 100% PG overnight at room temperature. Following staining, the embryos were washed with 100% PG for 30 min, then in 85% PG for 50 min and finally with 85% PG with equal volume of PBS for 40 min. Before adding 80% glycerol the embryos were washed with PBS. Bright field images were taken to assess the steatosis and yolk retention. For steatosis assessment, the larvae were considered to be positive when three or more round lipid droplets were visible within the hepatic parenchyma [28].

Results

Phytochemistry

The Frankincense essential oil has been analyzed by GC/MS to determine its main chemical components. A total of 23 active components were detected. The retention times ranged from 6.05 to 31.45 sec and the retention index from 900 to 1513 (Table 1).

|

Compound |

Retention time (sec) |

Retention index |

|

n-nonane |

6.050 |

900 |

|

tricyclene |

6.650 |

918 |

|

α-thujene |

6.820 |

923 |

|

α-pinene |

7.080 |

930 |

|

camphene |

7.610 |

946 |

|

thujadiene |

7.740 |

950 |

|

sabinene |

8.410 |

970 |

|

β-pinene |

8.580 |

975 |

|

β-mircene |

9.020 |

988 |

|

n-decane |

9.450 |

1000 |

|

δ-3-carene |

9.740 |

1007 |

|

P-cymene |

10.380 |

1023 |

|

limonene |

10.560 |

1027 |

|

eucalyptole |

10.680 |

1030 |

|

cis-sabinene hydrate |

12.370 |

1070 |

|

terpinolene |

12.920 |

1084 |

|

P-cymenene |

13.130 |

1089 |

|

linalool |

13.480 |

1097 |

|

n-undecane |

13.610 |

1100 |

|

fenchone |

13.930 |

1108 |

|

α-campholenol |

14.710 |

1125 |

|

trans-pinocarveol |

15.290 |

1139 |

|

cis-verbenol |

15.520 |

1144 |

|

pinocarvone |

16.250 |

1160 |

|

cis-sabinol |

16.690 |

1170 |

|

4-terpineol |

17.080 |

1180 |

|

p-cymen-8-ol |

17.410 |

1187 |

|

α-terpineol |

17.740 |

1195 |

|

n-dodecane |

18.07 |

1200 |

|

verbenone |

18.240 |

1204 |

|

trans-carveol |

18.840 |

1218 |

|

bornyl acetate |

21.660 |

1281 |

|

thymol |

22.240 |

1294 |

|

n-tridecane |

22.510 |

1300 |

|

carvacrol |

22.770 |

1306 |

|

δ-elemene |

24.390 |

1344 |

|

α-copamene |

25.580 |

1371 |

|

β-bourbonene |

25.900 |

1379 |

|

β-elemene |

26.180 |

1385 |

|

n-tetradecane |

26.82 |

1400 |

|

β-caryophyllene |

27.380 |

1414 |

|

α-humulene |

28.870 |

1450 |

|

allo-aromadendrene |

29.040 |

1454 |

|

γ-muurolene |

29.630 |

1470 |

|

β-eudesmene |

30.240 |

1483 |

|

azulene |

30.530 |

1490 |

|

n-pentadecane |

30.94 |

1500 |

|

γ-cadinene |

31.450 |

1513 |

Acute toxicity

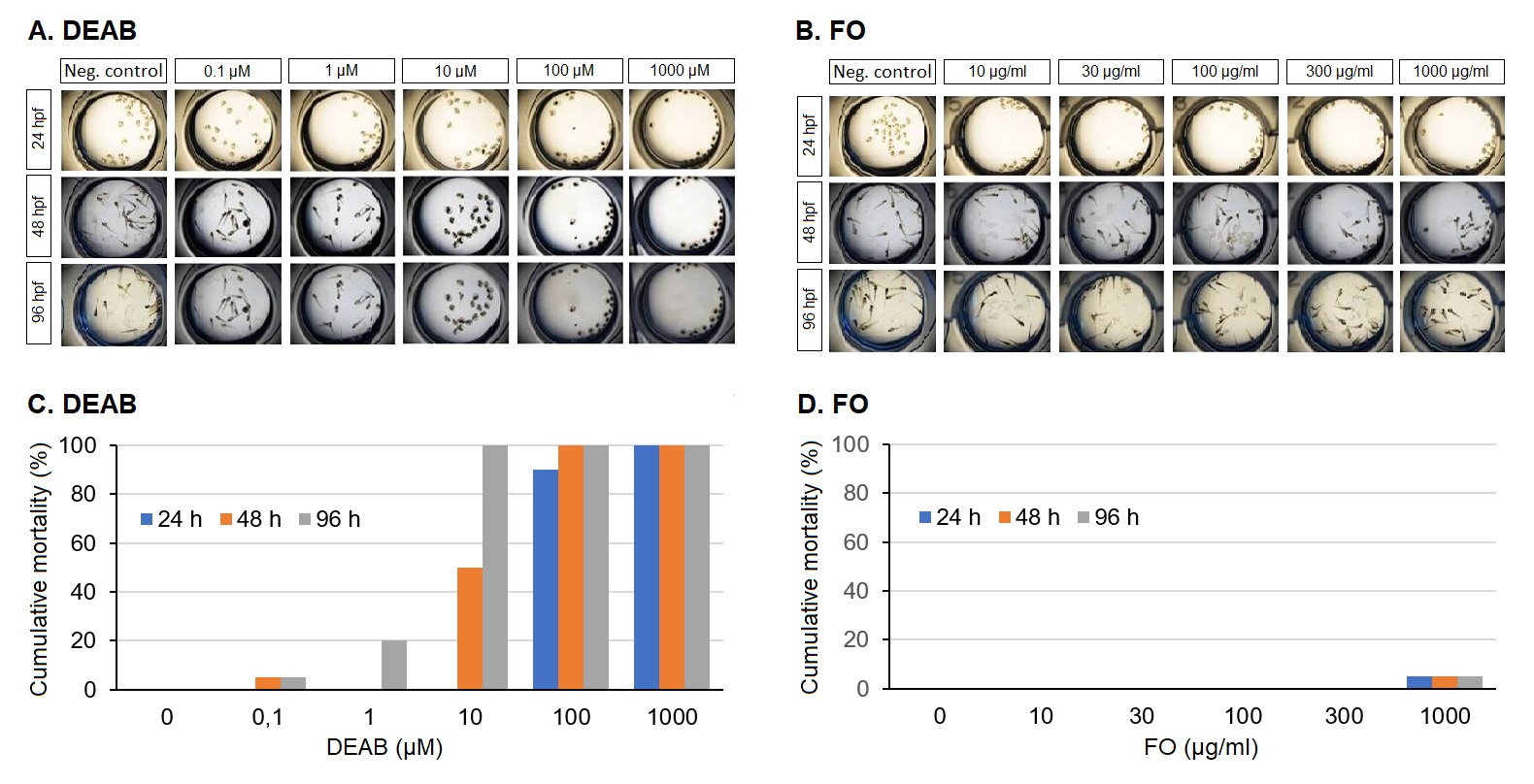

Cumulative toxicity: Exposure to 4-Diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB) at a concentration of 0.1 µM resulted in 5% cumulative mortality and increased to 100% in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Figure 1A). There was no cumulative mortality of Frankincense oil (FO) in a concentration range from 10 to 300 µg/ml upon exposure for 24, 48, or 96 h. Incubation with a high concentration of 1,000 µg/ml resulted in 5% mortality at all three incubation times (Figure 1B). The corresponding dose response curves for DEAB and FO are shown in Figure 1C. The log concentration vs. the percentage mortality response curve showed an upward trend with DEAB, while the FO values remained low.

Figure 1. Determination of acute toxicity of Frankincense oil. Representative images of zebrafish treated with different concentrations of (A) DEAB (positive control) and (B) FO. The mortality dose-response curves in (C) and (D) show the log concentration vs. percentage mortality response at various time points upon exposure to DEAB or Frankincense oil, respectively.

Teratogenicity: DEAB (10 µM) caused severe teratogenic effects, i.e., body deformation, pigmentation, and abnormalities in the yolk sac with 100% cumulative mortality. Thus, the “lowest observed effect concentration” (LOEC) of DEAB was 10 µM. FO (1,000 µg/ml) produced 5% mortality with mild teratogenic effects such as abnormalities in the yolk sac and cardiac oedema, and the final teratogenic score was found to be 28.57%. The “no observed effect concentration (NOEC) of FO was 100 µg/ml.

The E3 medium served as a vehicle control which did not provoke mortality or morphological changes in the embryos. Based on the above results, we have chosen 300 µg/ml FO as the highest concentration without causing cumulative mortality.

Genotoxicity

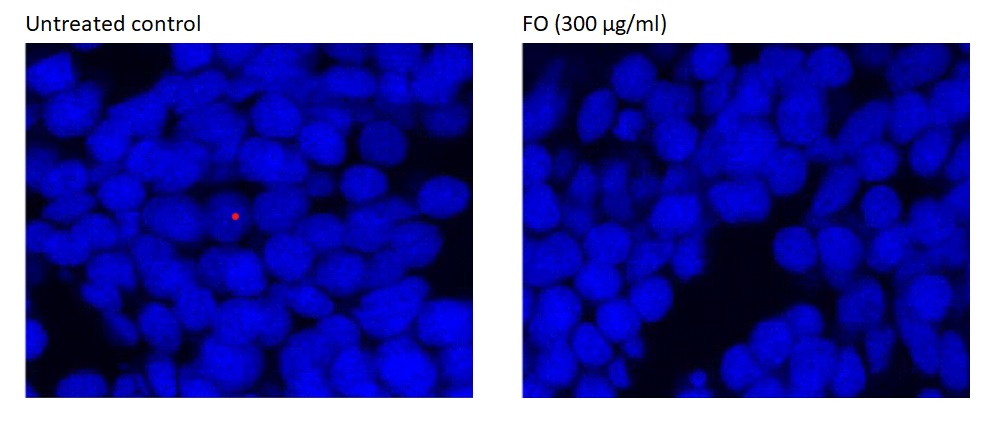

Exposure to Frankincense oil did not produce any genotoxic effects in zebrafish embryos if compared to DMSO-exposed zebrafish embryos (Figure 2). DAPI binds strongly to A-T rich DNA regions. It was used as a marker for cell membrane integrity. Frankincense oil treated zebrafish stained with DAPI did not show any ultrastructural changes compared to the appearance of the negative control zebrafish treated with DMSO (1%) in E3 medium.

Figure 2. Determination of genotoxicity of Frankincense oil. DAPI staining of zebrafish embryos treated with (left) DMSO (1%) in E3 medium (negative control) or (right) for 96 h using confocal microscopy.

Neuromuscular toxicity

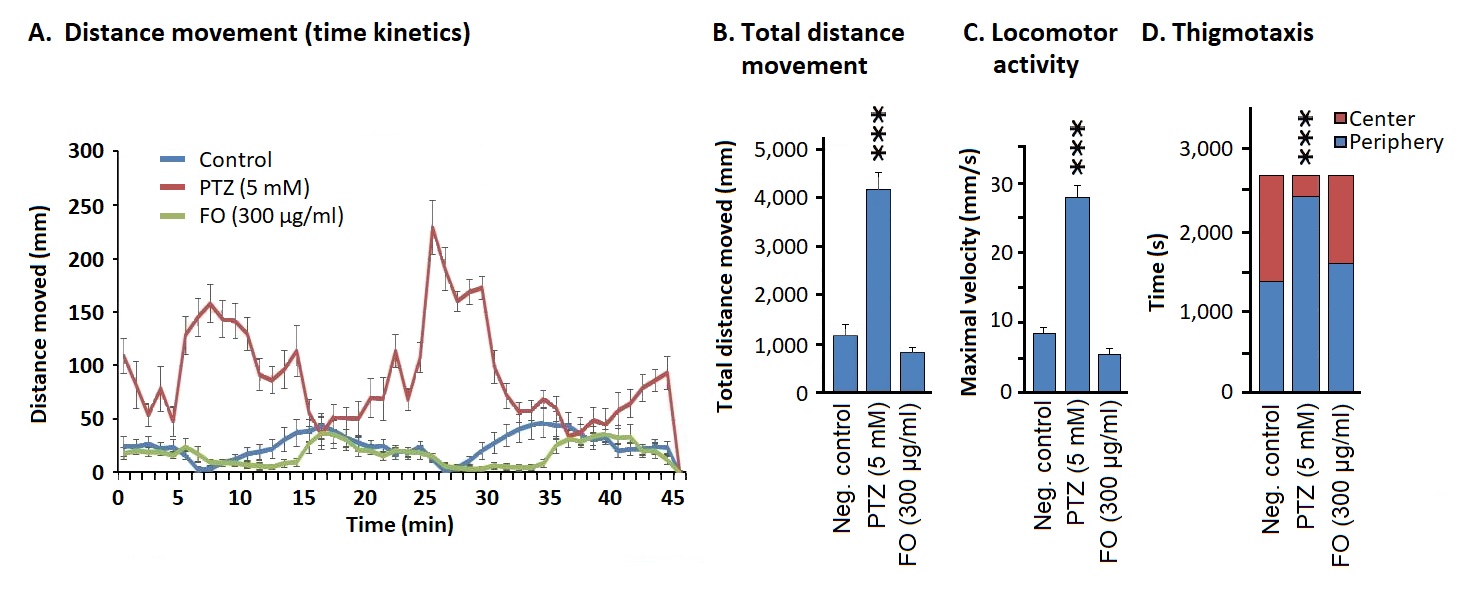

Distance movement assay: Pentelenetetrazol (PTZ)-exposed zebrafish embryos moved longer distances if compared to the negative control (1% DMSO in E3 medium) (Figure 3A). There was no significant difference in the distance moved between Frankincense- and vehicle-treated embryos. Typical diurnal (day/night) cycles in distance movements were observed for FO- and vehicle-treated embryos which were disturbed in PTZ-treated zebrafish (Figure 3A).

Locomotion assays: Then, we measured the maximal velocity of zebrafish. PTZ-treated group showed a significant increase in the maximum velocity if compared to the vehicle-treated group. FO (300 ug/ml) did not show any change in the maximum velocity if compared to the negative control group (Figure 3B).

Another parameter was the distance moved under light and dark (day/night) conditions. Again, the distances moved in the negative control group did not significantly differ from the FO-treated group, while the distances moved in the PTZ-treated group was significantly higher (Figure 3C).

Thigmotaxis assay: We measured the directed movement generated by thigmic stimuli (touch stimuli). PTZ-treated embryos spent significantly more time in the peripheral region of the water tank if compared to the negative control group (p<0.001), whereas the negative control group and FO-treated group spent equal time in both the center and periphery (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Determination of neurotoxicity of Frankincense oil. Distance movement assays: (A) distances moved by zebrafish upon treatment with PTZ, FO, or vehicle; (B) total distances moved upon treatment with FO or vehicle; (C) locomotor assay: maximal velocity of zebrafish upon treatment with PTZ, FO, or vehicle; (D) thigmotaxis analysis showing the time of zebrafish spent in the center or periphery of the water tank upon treatment with FO or vehicle.

Cardiotoxicity

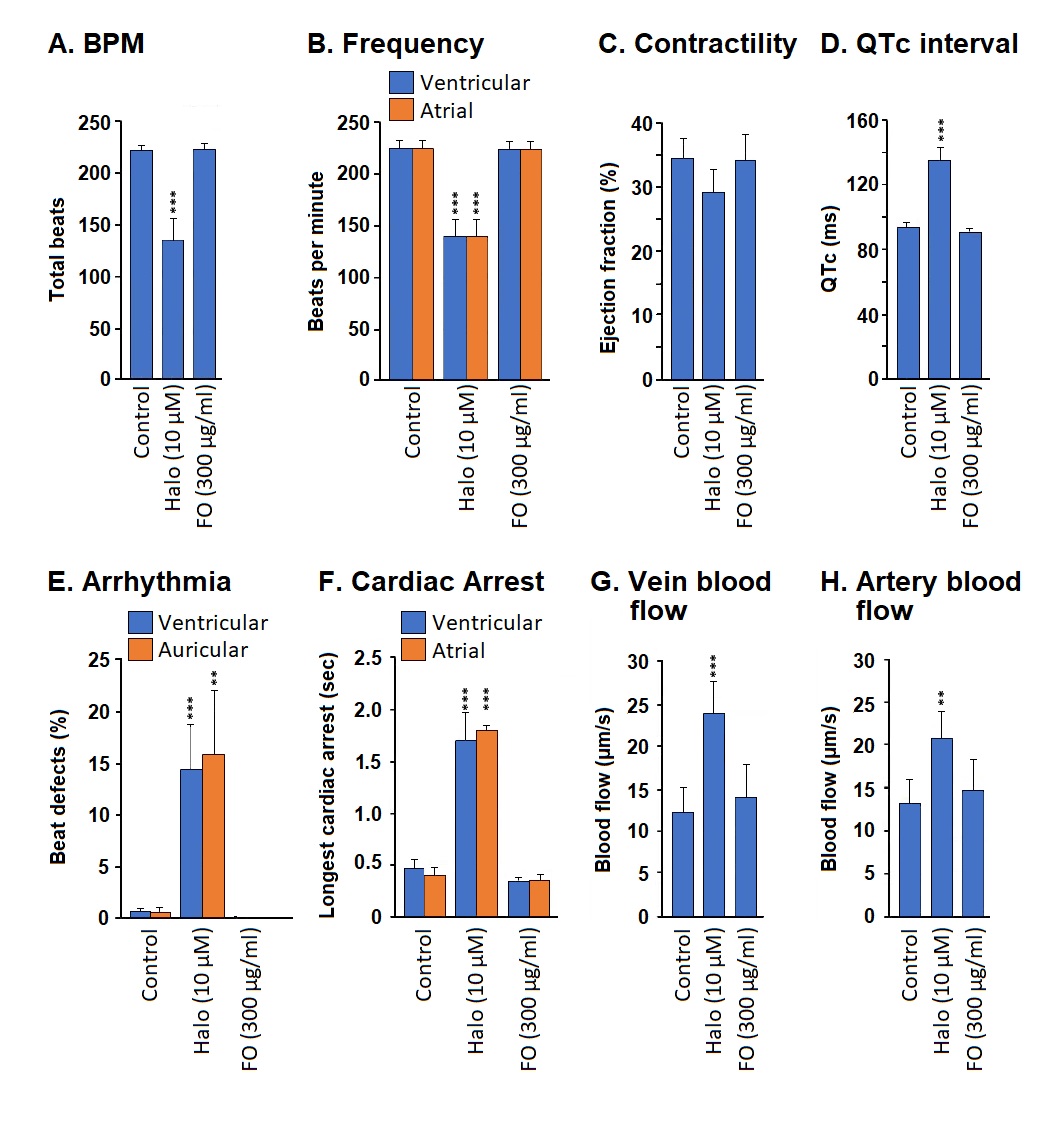

Cardiotoxicity was assessed by six parameters: (1) heartbeats per minute (BPM), (2) ejection fraction, (3) QT interval (QTc), which measures the time from the start of the Q wave to the end of the T wave, (4) auricular and ventricular arrhythmia, (5) cardiac arrest, and (6) the rate of blood flow.

Frequency (heartbeats per minute): Exposure to haloperidol (positive control) significantly decreased the BPM if compared to the vehicle treatment (p<0.001). There was no significant difference in BPM between the Frankincense oil- and vehicle-treated embryos (Figure 4A).

Treatment with haloperidol (positive control) significantly reduced both the atrial and ventricular BPM if compared to the negative control (p<0.01). In contrast, FO treatment did not significantly change the atrial and ventricular BPM (Figure 4B).

Contractility: Haloperidol or FO treatment did not significantly change the ejection fraction if compared to the negative control (Figure 4C).

QTc interval: Incubation with haloperidol significantly prolonged the QT interval if compared to negative control (p<0.001). However, FO incubation did not affect QTc (Figure 4D).

Arrhythmia: Haloperidol incubation significantly increased both the ventricular and auricular arrhythmia if compared to the negative control group (p<0.001), whereas Frankincense oil incubation did not show any irregularity in the cardiac rhythm (Figure 4E).

Cardiac arrest: The haloperidol-treated zebrafish embryos showed significantly increased incidences of cardiac arrest if compared to negative control. Frankincense oil did not cause any significant cardiac arrest incidence (Figure 4F).

Blood flow: Haloperidol incubation significantly increased the blood flow in veins (Figure 4G, p<0.001) and arteries (Figure 4H, p<0.01) if compared to E3 incubated negative control. Nevertheless, incubation with Frankincense oil did not significantly change both the arterial and venular blood flow if compared to the negative control.

Figure 4. Determination of cardiotoxicity of Frankincense oil. The cardiac function has been measured in terms of (A,B) frequency (total heartbeats per minute and ventricular or atrial heartbeats per minute), (C) contractility (ejection fraction), (D) QT interval (QTc) measuring the time from the start of the Q wave to the end of the T wave, (E) auricular and ventricular arrhythmia, (F) cardiac arrest, and (G,H) the rate of vein or artery blood flow.

Hepatotoxicity

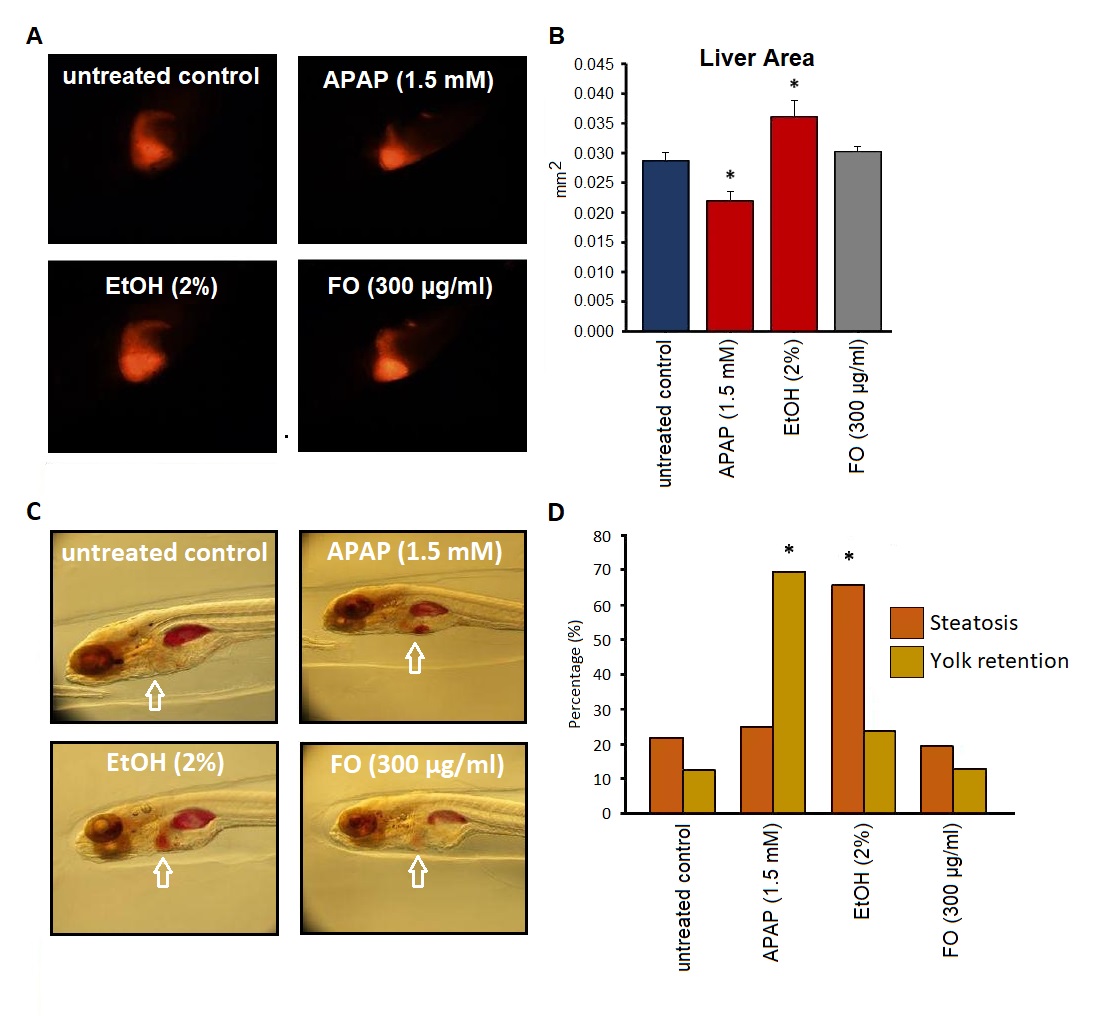

Acetaminophen-treated zebrafish (positive control) showed a significantly decreased liver size if compared to the negative control (p<0.05). In contrast, the ethanol (2%) treated group displayed a significantly increased liver size if compared to the vehicle-treated group (p<0.05). However, FO did not significantly change the liver size if compared to the vehicle-treated group (Figures 5A and 5B).

In addition, we also investigated the effect of Frankincense oil on steatosis and yolk retention. Ethanol-treated embryos showed a significant increase in steatosis if compared to DMSO-treated negative control embryos (p<0.05). In case of yolk retention, the APAP-treated embryos significantly increased in the yolk retention if compared to the DMSO-treated negative control (p<0.05). However, FO-treated embryos did not show any significant signs of steatosis and change in yolk retention if compared to the negative control group (Figures 5C and 5D).

Figure 5. Determination of hepatotoxicity of Frankincense oil. (A,B) Size of Red Fluorescent Protein (RFP)-expressing livers and (C,D) Steatosis and yolk retention. (A) Representative images of the treatment groups. (B) Quantification of the liver area (mm2): Embryos were treated with either acetaminophen (APAP), ethanol (EtOH), Frankincense oil (FO), or vehicle (negative control). (C) Representative zebrafish images of all treatment groups. (D) Percent steatosis and yolk retention in APAP-, EtOH-, FO- or vehicle-treated embryos.

Discussion

A plethora of human and animal studies reported the potential benefits of Frankincense oil for various diseases. The present study was designed to develop organ-specific toxicity profiles of Frankincense oil using the Zebrafish model. Frankincense oil at NOEC (300 µg/ml) did not show toxic signs in any of the studied organs. These results may facilitate to establish the pharmacological safety profile of the Frankincense oil using higher vertebrate models.

The Frankincense oil extract used for the present study was rich in major bio-constituents such as boswellic acids, mainly, α-pinene (79.59%), followed by δ-3-careen (9.94%), camphene (3.23%) and β-pinene (2.39%). Previous studies reported that the above-mentioned constituents contribute to the potential therapeutic properties of Frankincense oil [26]. The antioxidant properties of Frankincense oil have been well established: it is a potent scavenger of DPPH, OH, NO, O2, and peroxide radicals [29]. In addition, Su et al. found decreased expression of TNFα, PGE2, IL-2, NO, and MDA following Frankincense oil administration [30]. In this context, the authors attribute the above-mentioned properties of Frankincense oil aids to their pharmacological actions.

Zebrafish embryos are widely used for toxicological screening of new chemical compounds to understand the general toxicity, the teratogenicity profile, etc. Zebrafish embryos are more sensitive to chemical compounds than larval or adult fish [31]. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] also promoted the use of zebrafish to estimate NOEC, LOEC, and LC50 following the test guidelines such as OECD TG: 203 and 206 [24,25]. In the present study, the DEAB (10 µM) incubated embryos showed 100% mortality within 96 h. The above finding was consistent with previous studies. DEAB is a potent inhibitor of aldehyde dehydrogenase isoenzymes, thereby inducing cell death and mortality in colon cancer-derived HT-29/eGFP, HCT-116/eGFP, and LS-180/eGFP cell lines [32]. A recent study by Morgan et al. [33] showed that DEAB particularly inhibited ALDH3A1, ALDH2, and ALDH1A2 isoforms. The present study further warrants the effect of Frankincense oil and its bioactive constituents on aldehyde dehydrogenase enzyme activity, which might give more information on its safety profile.

Chemoconvulsant properties of pentelenetetrazol (PTZ) have been well established. PTZ acts by inhibiting the picrotoxin-binding site of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)A receptor complex [34]. Huang et al. [35] revealed that picrotoxin and PTZ interacted by overlapping but at different domains on the GABAA receptor. Also, PTZ produced abnormal ionic conductance by altering the sodium and potassium conductance via intracellular Ca2+ concentration [36]. We made similar observations in the present study, wherein exposure to PTZ escalated the locomotory movement of the zebrafish, thereby indicating the potential neuronal toxicity of PTZ in zebrafish. In the present study, exposure to Frankincense did not produce any abnormality in the locomotor functions in embryos, indicating that it does not interfere with GABAergic functions. On the other hand, Frankincense increased the number of neuronal processes in the hippocampal CA1 region and also improved memory in passive-avoidance learning task [37]. Furthermore, Frankincense oil administration alleviated the dendritic regression in the CA1 pyramidal cells of aged rats which revealed its neuroprotective properties with a good safety profile [38].

The cardiovascular system of the zebrafish is in close resemblance with the human system [39]. Therefore, the zebrafish model could be considered as a suitable model to assess the potential cardiotoxicity of the chemical substances [40]. Haloperidol caused bradycardia in both humans and zebrafish [41,42]. It also promoted QT prolongation by blocking the HERG potassium channels [43,44], and it blocked the sodium channels [45]. Frankincense oil incubation did not show any deviations in the cardiac functions viz heart rate, frequency, cardiac arrest, and blood flow if compared to the vehicle-treated haloperidol group. The above data indicate that Frankincense did not block the functions of the potassium or sodium channels in the tested concentrations and can, hence, be considered as free from cardiotoxic potential.

The liver is a major visceral organ highly prone to toxicity since it is highly perfused and has abundant metabolizing enzymes. In general, the metabolism of many chemical compounds produces toxic metabolites and by-products, e.g., paracetamol and carbon tetrachloride. Acetaminophen, the toxic metabolite of paracetamol is converted into N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI) which induces glutathione (GSH) depletion, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction leading to the depletion of ATP and cell death [46-48]. The above-mentioned changes results in fatty liver, steatosis, increased yolk retention and necrosis [49,50]. Frankincense did not show any abnormalities in the liver morphology, steatosis, and yolk retention. Chen et al., [51] reported the potent hepatoprotective properties of boswellic acid against acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity in Balb/c mice. They found that boswellic acid pre-treatment maintained the GSH levels and also glutathione reductase activity and suppressed the protein expression of inflammatory markers such as CYP2E1, NF-κB p65, JNK, TLR-3, and TLR-4. The present study showed that Frankincense oil is free from hepatotoxicity in the tested concentrations in zebrafish. In summary, the present study revealed that Frankincense was safe regarding organ-specific toxicity (cells, neurons, heart, and liver) in the tested conditions and concentrations. Nevertheless, further studies are warranted in higher phylogenetic models to provide more information on the safety profile.

Conclusion

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the present study is the first one to establish the organ-specific toxicity profile of Frankincense oil in a zebrafish model. There were no signs of genotoxic, neurotoxic, cardiovascular, and hepatotoxic effects of Frankincense oil, and the NOEC was 100 µg/ml in the zebrafish model at the test conditions.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during the present study are included in this published article.

Competing / conflicts of interest

L.R. discloses patents EP1803461A1 and 20200345801. The other authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Funding

No outside supported funds were received.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank their institutions for continued support.

References

2. Shen T, Lou HX. Bioactive constituents of myrrh and frankincense, two simultaneously prescribed gum resins in Chinese traditional medicine. Chemistry & Biodiversity. 2008 Apr;5(4):540-53.

3. Rashan L, Hakkim FL, Idrees M, Essa MM, Velusamy T, Al-Baloshi M, Al-Balushi BS, Al Jabri A, Al-Rizeiqi MH, Guillemin GJ, Hasson SSet al. Boswellia gum resin and essential oils: potential health benefits− an evidence based review. International Journal of Nutrition, Pharmacology, Neurological Diseases. 2019 Apr 1;9(2):53-71.

4. Hamidpour R, Hamidpour S, Hamidpour M, Shahlari M. Frankincense (Boswellia Species): From the selection of traditional applications to the novel phytotherapy for the prevention and treatment of serious diseases. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2013 Oct;3(4):221-6.

5. Mathe C, Connan J, Archier P, Mouton M, Vieillescazes C. Analysis of frankincense in archaeological samples by gas chromatography‐mass spectrometry. Annali di Chimica: Journal of Analytical, Environmental and Cultural Heritage Chemistry. 2007 Jun;97(7):433-45.

6. de Rapper S, Van Vuuren SF, Kamatou GP, Viljoen AM, Dagne E. The additive and synergistic antimicrobial effects of select frankincense and myrrh oils--a combination from the pharaonic pharmacopoeia. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2012 Apr;54(4):352-8.

7. Başer KH, Demirci B, Dekebo A, Dagne E. Essential oils of some Boswellia spp., myrrh and opopanax. Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 2003 Mar;18(2):153-6.

8. Camarda L, Dayton T, Di Stefano V, Pitonzo R, Schillaci D. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of some oleogum resin essential oils from Boswellia spp.(Burseraceae). Annali di Chimica: Journal of Analytical, Environmental and Cultural Heritage Chemistry. 2007 Aug;97(9):837-44.

9. Chevrier MR, Ryan AE, Lee DY, Zhongze M, Wu-Yan Z, Via CS. Boswellia carterii extract inhibits TH1 cytokines and promotes TH2 cytokines in vitro. Clinical and Diagnostic Laboratory Immunology. 2005 May;12(5):575-80.

10. Park YS, Lee JH, Bondar JH, JA S. H. and Golubic, M.(2002). Cytotoxic action of acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA) on meningioma cells. Plantae Medical.;68:397-401.

11. Poeckel D, Tausch L, Kather N, Jauch J, Werz O. Boswellic acids stimulate arachidonic acid release and 12-lipoxygenase activity in human platelets independent of Ca2+ and differentially interact with platelet-type 12-lipoxygenase. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006 Sep 1;70(3):1071-8.

12. Lamb DC, Lei L, Warrilow AG, Lepesheva GI, Mullins JG, Waterman MR, et al. The first virally encoded cytochrome p450. Journal of Virology. 2009 Aug 15;83(16):8266-9.

13. Siddiqui MZ. Boswellia serrata, a potential antiinflammatory agent: an overview. Indian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2011 May;73(3):255.

14. Jeong JY, Kwon HB, Ahn JC, Kang D, Kwon SH, Park JA, et al. Functional and developmental analysis of the blood–brain barrier in zebrafish. Brain Research Bulletin. 2008 Mar 28;75(5):619-28.

15. Goldstone JV, McArthur AG, Kubota A, Zanette J, Parente T, Jönsson ME, et al. Identification and developmental expression of the full complement of Cytochrome P450 genes in Zebrafish. BMC Genomics. 2010 Dec;11(1):1-21.

16. Li ZH, Alex D, Siu SO, Chu IK, Renn J, Winkler C, et al. Combined in vivo imaging and omics approaches reveal metabolism of icaritin and its glycosides in zebrafish larvae. Molecular BioSystems. 2011;7(7):2128-38.

17. Milan DJ, Peterson TA, Ruskin JN, Peterson RT, MacRae CA. Drugs that induce repolarization abnormalities cause bradycardia in zebrafish. Circulation. 2003 Mar 18;107(10):1355-8.

18. Tiso N, Moro E, Argenton F. Zebrafish pancreas development. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinologsssssy. 2009 Nov 27;312(1-2):24-30.

19. Ganis JJ, Hsia N, Trompouki E, de Jong JL, DiBiase A, Lambert JS, et al. Zebrafish globin switching occurs in two developmental stages and is controlled by the LCR. Developmental Biology. 2012 Jun 15;366(2):185-94.

20. Singh P, Chacko KM, Aggarwal ML, Bhat B, Khandal RK, Sultana S, Kuruvilla BT et al. A-90 day gavage safety assessment of Boswellia serrata in rats. Toxicology International. 2012 Sep;19(3):273.

21. Devi PS, Adilaxmamma K, Rao G, Srilatha C, Raj M. Safety evaluation of alcoholic extract of Boswellia ovalifoliolata stem-bark in rats. Toxicology International. 2012 Jul 1;19(2):115.

22. Al-Yahya AA, Asad M, Sadaby A, Alhussaini MS. Repeat oral dose safety study of standardized methanolic extract of Boswellia sacra oleo gum resin in rats. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020 Jan 1;27(1):117-23.

23. Han L, Xia Q, Zhang L, Zhang X, Li X, Zhang S, et al. Induction of developmental toxicity and cardiotoxicity in zebrafish embryos/larvae by acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid (AKBA) through oxidative stress. Drug and Chemical Toxicology. 2022 Jan 2;45(1):143-50.

24. OECD iLibrary. OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals, section 2. Test No. 203: Fish, Acute Toxicity Test [Internet]. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/test-no-203-fish-acute-toxicity-test_9789264069961-en (accessed on April 4, 2023).

25. OECD iLibrary. OECD guidelines for the testing of chemicals, section 2. Test No. 206: Avian Reproduction Test [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 29]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/test-no-206-avian-reproduction-test_9789264070028-en (accessed on March 1, 2023).

26. Di Stefano V, Schillaci D, Cusimano MG, Rishan M, Rashan L. In vitro antimicrobial activity of Frankincense oils from Boswellia sacra grown in different locations of the Dhofar region (Oman). Antibiotics (Basel). 2020;9:195.

27. Nordgreen J, Tahamtani FM, Janczak AM, Horsberg TE. Behavioural effects of the commonly used fish anaesthetic tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) on zebrafish (Danio rerio) and its relevance for the acetic acid pain test. PLoS One. 2014 Mar 21;9(3):e92116.

28. Howarth DL, Yin C, Yeh K, Sadler KC. Defining hepatic dysfunction parameters in two models of fatty liver disease in zebrafish larvae. Zebrafish. 2013 Jun 1;10(2):199-210.

29. Sharma A, Upadhyay J, Jain A, Kharya MD, Namdeo A, Mahadik KR. Antioxidant activity of aqueous extract of Boswellia Serrata. J Chem Bio Phy Sci. 2011 Jan 1;1:60-71.

30. Su S, Duan J, Chen T, Huang X, Shang E, Yu L, Wei K, Zhu Y, Guo J, Guo S, Liu P et al. Frankincense and myrrh suppress inflammation via regulation of the metabolic profiling and the MAPK signaling pathway. Scientific Reports. 2015 Sep 2;5(1):1-5.

31. Beheshti S, Aghaie R. Therapeutic effect of frankincense in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Avicenna Journal of Phytomedicine. 2016 Jul;6(4):468.

32. Kozovska Z, Patsalias A, Bajzik V, Durinikova E, Demkova L, Jargasova S, Smolkova B, Plava J, Kucerova L, Matuskova M et al. ALDH1A inhibition sensitizes colon cancer cells to chemotherapy. BMC Cancer. 2018 Dec;18(1):1-1.

33. Morgan CA, Parajuli B, Buchman CD, Dria K, Hurley TD. N, N-diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB) as a substrate and mechanism-based inhibitor for human ALDH isoenzymes. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2015 Jun 5;234:18-28.

34. Ramamjaneyulu R, Ticku MH. Interactions of pentamethylenetetrazol and tetrazole analogues with the picrotoxinin site of the benzodiazepine-GABA receptor-ionophore complex. Eur J Pharmacol. 1984;98:337-45.

35. Huang RQ, Bell-Horner CL, Dibas MI, Covey DF, Drewe JA, Dillon GH. Pentylenetetrazole-induced inhibition of recombinant gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA(A)) receptors: mechanism and site of action. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001 Sep;298(3):986-95.

36. Bazyan AS, Zhulin VV, Karpova MN, Klishina NY, Glebov RN. Long-term reduction of benzodiazepine receptor density in the rat cerebellum by acute seizures and kindling and its recovery 6 months later by a pentylenetetrazole challenge. Brain Research. 2001 Jan 12;888(2):212-20.

37. Sharma P, Kumari S, Sharma J, Purohit R, Singh D. Hesperidin interacts with CREB-BDNF signaling pathway to suppress pentylenetetrazole-induced convulsions in zebrafish. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2021 Jan 11;11:607797.

38. Jalili C, Salahshoor MR, Moradi S, Pourmotabbed A, Motaghi M. The therapeutic effect of the aqueous extract of boswellia serrata on the learning deficit in kindled rats. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2014 May;5(5):563.

39. Bakkers J. Zebrafish as a model to study cardiac development and human cardiac disease. Cardiovascular Research. 2011 Jul 15;91(2):279-88.

40. Han Y, Zhang JP, Qian JQ, Hu CQ. Cardiotoxicity evaluation of anthracyclines in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2015 Mar;35(3):241-52.

41. Milan DJ, Jones IL, Ellinor PT, MacRae CA. In vivo recording of adult zebrafish electrocardiogram and assessment of drug-induced QT prolongation. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2006 Jul;291(1):H269-73.

42. Girardin F, Sztajzel J. Cardiac adverse reactions associated with psychotropic drugs. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 2007 Mar;9(1):92.

43. Taglialatela M, Castaldo P, Pannaccione A, Giorgio G, Annunziato L. Human ether-a-gogo related gene (HERG) K channels as pharmacological targets: present and future implications. Biochemical Pharmacology. 1998 Jun 1;55(11):1741-6.

44. Ehret GB, Voide C, Gex-Fabry M, Chabert J, Shah D, Broers B, et al. Drug-induced long QT syndrome in injection drug users receiving methadone: high frequency in hospitalized patients and risk factors. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2006 Jun 26;166(12):1280-7.

45. Ogata N, Narahashi T. Block of sodium channels by psychotropic drugs in single guinea-pig cardiac myocytes. British Journal of Pharmacology. 1989 Jul;97(3):905.

46. Clark R, Fisher JE, Sketris IS, Johnston GM. Population prevalence of high dose paracetamol in dispensed paracetamol/opioid prescription combinations: an observational study. BMC Clinical Pharmacology. 2012 Dec;12(1):1-8.

47. Jaeschke H, McGill MR. Cytochrome P450-derived versus mitochondrial oxidant stress in acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Toxicology Letters. 2015 Jun 15;235(3):216-7.

48. Jaeschke H, McGill MR, Ramachandran A. Oxidant stress, mitochondria, and cell death mechanisms in drug-induced liver injury: lessons learned from acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Drug Metabolism Reviews. 2012 Feb 1;44(1):88-106.

49. He JH, Guo SY, Zhu F, Zhu JJ, Chen YX, Huang CJ, Gao JM, Dong QX, Xuan YX, Li et al. A zebrafish phenotypic assay for assessing drug-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2013 Jan 1;67(1):25-32.

50. Ginting CN, Lister IN, Girsang E, Widowati W, Yusepany DT, Azizah AM, et al. Hepatotoxicity prevention in Acetaminophen-induced HepG2 cells by red betel (Piper crocatum Ruiz and Pav) extract from Indonesia via antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-necrotic. Heliyon. 2021 Jan 1;7(1):e05620.

51. Chen LC, Hu LH, Yin MC. Alleviative effects from boswellic acid on acetaminophen-induced hepatic injury - Corrected and republished from: Biomedicine (Taipei). 2016 Jun;6(2):9. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2017 Jun;7(2):13.