Abstract

Glycine-proline-glutamate (GPE) and cycloprolylglycine (cPG) are naturally cleaved peptides of the insulinlike growth factor I (IGF-I) in the central nervous system. The neuroprotective actions of IGF-I have been widely studied in experimental models of Alzheimer´s disease (AD) and AD patients. However, there is less data about the molecular mechanisms involved in the protective effects of both IGF-I derived peptides in murine models of this disease. Here, we have analyzed the key issues of our study on the effects of GPE and cPG in a murine model of amyloid-β peptide infusion and revised the research progress on the effects of both compounds and new analogues of these molecules against inflammation, its relationship with the expression and synthesis of hormones implicated in memory processes and the intracellular signaling pathways related to these protective effects. Understanding the molecular mechanisms involved in the action of these molecules in experimental models of AD will help to develop strategies to fight one of the most common neurological diseases.

Keywords

Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, GPE, Cycloprolylglycine, Inflammation, Neuroprotection, Signaling, Somatostatin

Abbreviations

Aβ: Amyloid-β peptide; AD: Alzheimer´s disease; AMPA: α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; cPG: cycloprolylglycine; CREB: cAMP response element-binding protein; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GABA: γ-aminobutyric acid; GFAP: Glial fibrillary acidic protein; GPE: Glycine-proline-glutamate; GRK: G-protein-coupled receptor kinase; GSK3β: Glycogen synthase kinase-3β; ICV: Intracerebroventricular; IGF-I: Insulin-like growth factor I; JNK: c-Jun N-terminal kinase; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; PI3K: Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase; p70S6K: p70 ribosomal S6 kinase; SRIF: Somatostatin.

Commentary

Alzheimer´s disease (AD) is a devastating disease caused by the accumulation and interaction of tau-containing neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid beta peptide (Aβ) plaques in the brain [1,2]. The increased production and deposition of Aβ peptides results in microglial activation, and the production of inflammatory cytokines further increases Aβ synthesis [3], leading to neuronal death and pathological changes in astrocytes that impair Aβ clearance [4].

This disease is the most common cause of cognitive impairment, being associated with a decrease in numerous neurotransmitters in the brain and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with AD [5]. One of the most affected is somatostatin [6], which is widely distributed in the hippocampus and is involved in the control of cognitive functions. Furthermore, the reduction of SRIF levels in the cerebrospinal fluid is directly related to the severity of this disease [7]. Intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion of Aβ is an experimental approach to this disease, since it increases Aβ deposition in the hippocampus, along with an increase in neuronal death and alterations in synaptic plasticity, neurotransmitter levels, learning and memory [8]. It also reduces SRIF levels in the brain [9], with the Aβ25-35 fragment having a greater deleterious effect on the cerebral somatostatinergic system than Aβ1-42 peptide [10]. In this regard, a decrease in the number of receptors for this neuropeptide has been described in AD patients, along with a decrease in SRIF levels [11].

Various approaches have been tried to block Aβ toxicity and reduce the progression of AD. Among them, the administration of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) in experimental models of the disease, which acts as a neurotrophic and survival factor by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway [12]. We have reported that co-administration of IGF-I with Aβ25-35 reduced cell death in the hippocampus, associated with an increase in Aβ-degrading enzymes [13]. This increase appeared to be associated with the restoration of hippocampal SRIF levels, as this neuropeptide stimulates neprilysin and insulin-degrading-enzyme (IDE) activities [14,15]. However, although brain levels of IGF-I are reduced in AD patients [16], its limited ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and possible mitogenic effects limits its clinical use [17,18].

Enzymatic degradation of IGF-I at its N-terminal portion generates the tripeptide glycine-proline-glutamate (GPE), which is present in the circulation and brain [19]. A dipeptide, cycloprolylglycine (cGP) is formed from GPE, by cyclization after enzymatic cleavage of glutamate [20]. These small peptides exhibit pharmacological effects similar to those of IGF-I showing anti-inflammatory properties and protective effects after ischemic injury or Aβ infusion in the brain [21-23]. Similarly, GPE reduces cell death and microglial activation, and the effects of cGP are mediated by stabilizing IGF-I bioavailability, and consequently its function [24,25]. It is also important to note that, like IGF-I, GPE has a protective effect on the SRIF receptor-effector system in the temporal cortex in experimental models of AD [26].

Although these peptides were discovered more than three decades ago, their use has been limited and confined to experimental models of neurodegenerative diseases. This is partly due to the relatively short half-life of these compounds in serum [27], although the activity of proteases is lower in the central nervous system, and therefore, the half-life is longer [28]. Nevertheless, to maintain effective plasma levels of GPE, continuous intravenous administration may improve neuroprotection after brain damage [29]. There are also limitations in our knowledge of the neuroprotective mechanisms of these molecules; for example, although it interacts with glutamate receptors, the prevention of neuronal death by GPE and its analogues is not directly related to its affinity for these receptors [30]. Controversial actions have also been described, and thus, although GPE can bind to NMDA receptors and act as an antagonist, protecting hippocampal neurons from NMDA-induced toxicity “in vitro” [31], it can also be a weak agonist of these receptors [32]. Another problem with the use of these molecules is a selective protective effect on certain neurons; thus, after brain damage the infusion of these peptides prevents the loss of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)- and SRIFergic neurons, but not of those containing parvalbumin [21].

To avoid such instability problems, conjugates of these compounds with different functional groups have been created. Data in the literature indicate that in most cases GPE is an NMDA receptor antagonist, alleviating the harmful effects of glutamate overload, but with low affinity for this receptor [33], so new compounds with a higher affinity and a longer half-life have been designed. In this way, both compounds regulate IGF-I bioavailability by modifying the IGF-I binding to the IGF-I binding protein-3 [34] and new pseudopeptides show longer half-lives in plasma and good water solubility, modifying inflammatory state after Aβ exposure [35]. However, it has been reported that some analogs show biases in neuroprotection levels, depending on the design of the conjugates [36], so more work is needed to research new compounds for a greater efficacy in reducing the causes of AD. Another problem is that systemic administration of certain molecules may cause peripheral side effects in other tissues. Therefore, intranasal administration of nanoparticles is a strategy to be considered in this disease, given their ease of crossing the blood-brain barrier [37].

The use of these peptides is also limited by the lack of studies that have analyzed in depth the molecular mechanisms associated with their anti-inflammatory properties [35] and their association with neurotransmitter receptor-effector systems and signaling pathways involved in these protective actions. On this way, the few studies that have been carried out show that that GPE interacts with N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and cPG excites α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptors [38], albeit usually with lower affinity at physiological brain levels. Therefore, higher concentrations of both molecules must be achieved locally, usually after treatments, in order to improve synaptic transmission [39]. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt pathway is one of the keys signaling cascades that can modulate NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic plasticity and contribute to long-term potentiation [40].

Although both peptides mimic many of the effects of IGF-I, they do not bind to its receptor. Using autoradiographic techniques, it has been shown "in vivo" that GPE binds to glial cells [41] and that the effects of GPE and des-IGF-I, the molecule derived from the tripeptide rem differ in their actions in glia, since blockade of NMDA receptors prevented the effects of GPE in these cells, whereas the additive effects of both molecules indicate that des-IGF-I acts through IGF-I receptors [42]. Data on the actions of both peptides on neurons mostly refer to “in vitro” studies. In the studies of neuroprotective and proliferative effects in neural stem cell cultures, they have been described as being related to the activation of survival pathways and neuroprotective factors [43,44]. However, there are data suggesting that the neuroprotective actions of GPE are not as evident, as it binds weakly to the dentate gyrus, where NMDA receptors are highly expressed [45].

Therefore, to gain insight into the mechanisms of both peptides involved in the protection/restoration of the SRIF system, involved in learning and memory processes, we had studied the hippocampal effects of co-administration of GPE or cPG in an experimental model of AD, based on chronic ICV infusion of Aβ25-35 [46]. Intraperitoneal injections of 300 µg of GPE or cPG at 0, 6 and 12 days were used, based on previous reports with similar concentrations and routes of administration [22,41,47]. In these previous publications both peptides were shown to exert numerous benefits after neuronal damage caused by Aβ or ischemia. These include their protective role on neurotransmitters involved in learning and memory processes through cytosolic calcium modulation, increased neuronal survival mediated by glial cells and the prevention of sensorimotor impairments stand out. In a first set of studies, we analyzed the effect of both peptides on the β-amyloid-induced cell death and depletion of SRIFergic system in the hippocampus. Both IGF-I metabolites reduced Aβ-induced cell death and depletion of the hippocampal SRIFergic system, with GPE being more effective than cPG and related to the reduction of c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation.

The toxic effects of Aβ peptides, as well as the protective effects of GPE and cPG are modulated by opposing changes in common signaling pathways, that ultimately regulate, among other actions, cell death and the implementation of neurotransmitter systems [43,48]. We therefore examined the activation of different signaling targets that can be grouped into two different pathways, Akt/cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)/ G-protein-coupled receptor kinase (GRK), which converge on the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR)/p70 ribosomal S6 kinase (p70S6K). Our results showed restoration of Akt phosphorylation in Aβ-treated rats when GPE was co-administered, together with blockade of JNK and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) and an increase in CREB activation. Blockade of these targets is associated with a reduction in cell death, and probably with a protective effect on the SRIFergic system [49]. In addition, the increase in CREB phosphorylation can directly increase SRIF and SRIF receptor 2, as both genes have CRE sites [50,51] and we detected an increase in both mRNA levels after co-administration of GPE [46].

Co-administration of cPG did not modify either GSK3β or CREB phosphorylation, but increased ERK1/2 and GRK2 activation. ERK phosphorylation upregulates the transcription of GRK2 [52], and this protein phosphorylates SRIF receptor 2, potentiating the SRIF receptor-effector system [53]. It is noteworthy that both IGF-I metabolites activate, through different pathways, the phosphorylation of p70S6K, a crucial factor in protein synthesis, with translational control at synapses required for the development of long-term memory [54].

This neurodegenerative disease is associated with increased brain inflammation and astrogliosis [55,56]. In our study [46], we had found an increase in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and vimentin levels in Aβ-treated rats, together with an increase in the inflammatory environment, as reported [57]. Co-administration of these peptides favored the generation of an anti-inflammatory profile, i.e., GPE binds to astrocytes and promote their survival, which is associated with reduced brain inflammation in models of neurodegenerative disorders [58].

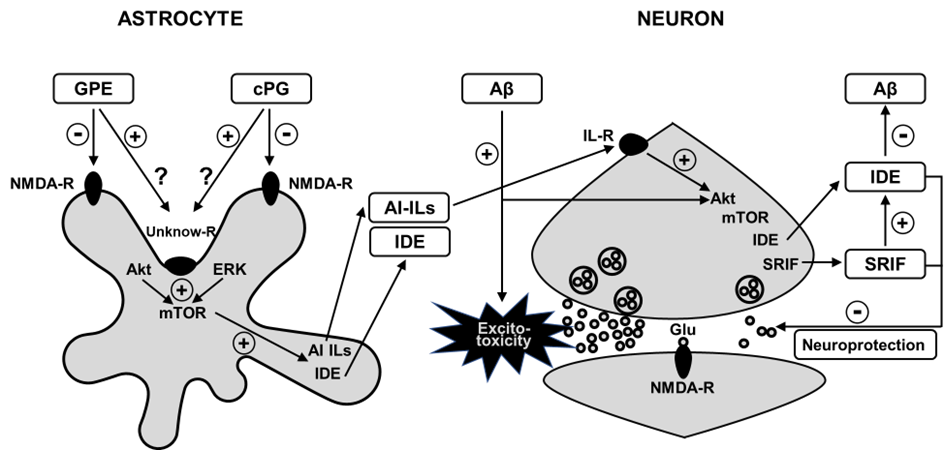

In turn, anti-inflammatory interleukins (IL) may play a relevant role in altering survival signaling pathways and the functionality of brain neurotransmitter systems [59,60]. Consequently, we had chosen IL-4, which was increased after co-administration of GPE or cPG and analyzed its effect on Akt phosphorylation and SRIF levels “in vitro”. IL-4 increased Akt activation and SRIF levels in neuronal cultures. Furthermore, Aβ25-35 plus GPE or cPG increased IL-4 levels in glial cell cultures. These data show that at least some of the effects of both small peptides are mediated by changes in the inflammatory environment that activate survival pathways. The most remarkable feature of this study is that both peptides in most cases prevented Aβ-induced changes in signaling pathways modulating anti-inflammatory processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Proposed model for reduction in hippocampal Aβ levels after GPE or cPG administration to Aβ25-35 treated rats. Infusion of Aβ reduces Akt signaling, whereas both peptides activate it. After binding them to NMDA receptors or to a possible unknow receptor in astrocytes, Akt activation may produce a rise in mTOR hosphorylation, increasing insulin-degrading enzyme and anti-inflammatory cytokines. These cytokines may bind to receptors in neurons, enhancing Akt-related ignaling, and subsequently; IDE and SRIF synthesis, that in turn reduce Aβ content. Thus, these events can improve neuroprotection by inhibiting Aβ-induced excitotoxicity. Aβ: β-amyloid 25-35 peptide; AI-ILs: Anti-inflammatory interleukins; Akt: Protein kinase B; cPG: cycloprolylglycine; ERK: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase; GPE: Gly-Pro-Glu; glu: glutamate; IDE: Insulin-degrading-enzyme; IL-R: IL-receptor; mTOR: mechanistic target of rapamycin; NMDA-R: N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor; SRIF: somatostatin.

In summary, our study demonstrated that GPE and cPG attenuation increased cell death and inflammation in an experimental model of AD disease. The intracellular signaling mechanisms involved in the protective effects of the two IGF-I-derived peptides are different, although their protective effects were mediated by the activation of targets associated with protein synthesis and memory consolidation, coinciding with the restoration of a neurotransmitter system involved in cognitive processes. Recent reports have shown that cPG normalizes IGF-I function in age-related neurological situations [61] and reduces amyloid plaque burden, thereby, improving memory in a transgenic model of AD [62]. It should also be noted that different peptidomimetics of GPE modulate oxidative stress and inactivate α-secretase, thereby reducing cell death by apoptosis and necrosis [63]. In fact, the development of analogs of these small peptides is providing compounds with longer half-lives and lack of cytotoxicity [64], which may allow their future use in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Funding

This work received no external funding.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

2. Busche MA, Hyman BT. Synergy between amyloid-β and tau in Alzheimer's disease. Nature Neuroscience. 2020 Oct;23(10):1183-1193.

3. Wang H, Sun M, Li W, Liu X, Zhu M, Qin H. Biomarkers associated with the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2023 Dec 7;17:1279046.

4. Kim J, Yoo ID, Lim J, Moon JS. Pathological phenotypes of astrocytes in Alzheimer's disease. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2024 Jan 4;56:95-9.

5. Yang Z, Zou Y, Wang L. Neurotransmitters in prevention and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 Feb 14;24(4):3841.

6. Burgos-Ramos E, Hervás-Aguilar A, Aguado-Llera D, Puebla-Jiménez L, Hernández-Pinto AM, Barrios V, et al. Somatostatin and Alzheimer's disease. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2008 May 14;286(1-2):104-11.

7. Nilsson CL, Brinkmalm A, Minthon L, Blennow K, Ekman R. Processing of neuropeptide Y, galanin, and somatostatin in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Peptides. 2001 Dec;22(12):2105-12.

8. Wu X, Lv YG, Du YF, Chen F, Reed MN, Hu M, et al. Neuroprotective effects of INT-777 against Aβ1-42-induced cognitive impairment, neuroinflammation, apoptosis, and synaptic dysfunction in mice. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2018 Oct;73:533-545.

9. Aguado-Llera D, Arilla-Ferreiro E, Chowen JA, Argente J, Puebla-Jiménez L, Frago LM, et al. 17Beta-estradiol protects depletion of rat temporal cortex somatostatinergic system by beta-amyloid. Neurobiology of Aging. 2007 Sep;28(9):1396-409.

10. Aguado-Llera D, Arilla-Ferreiro E, Campos-Barros A, Puebla-Jiménez L, Barrios V. Protective effects of insulin-like growth factor-I on the somatostatinergic system in the temporal cortex of beta-amyloid-treated rats. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2005 Feb;92(3):607-15.

11. Ádori C, Glück L, Barde S, Yoshitake T, Kovacs GG, Mulder J, et al. Critical role of somatostatin receptor 2 in the vulnerability of the central noradrenergic system: new aspects on Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathologica. 2015 Apr;129(4):541-63.

12. Jacobsen KT, Adlerz L, Multhaup G, Iverfeldt K. Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1)-induced processing of amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP) and APP-like protein 2 is mediated by different metalloproteinases. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010 Apr 2;285(14):10223-31.

13. Aguado-Llera D, Canelles S, Frago LM, Chowen JA, Argente J, Arilla E, et al. The protective effects of IGF-I against β-amyloid-related downregulation of hippocampal somatostatinergic system involve activation of Akt and protein kinase A. Neuroscience. 2018 Mar 15;374:104-18.

14. Watamura N, Kakiya N, Nilsson P, Tsubuki S, Kamano N, Takahashi M, et al. Somatostatin-evoked Aβ catabolism in the brain: Mechanistic involvement of α-endosulfine-KATP channel pathway. Molecular Psychiatry. 2022 Mar;27(3):1816-28.

15. Tundo G, Ciaccio C, Sbardella D, Boraso M, Viviani B, Coletta M, et al. Somatostatin modulates insulin-degrading-enzyme metabolism: implications for the regulation of microglia activity in AD. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34376.

16. Kang K, Bai J, Zhong S, Zhang R, Zhang X, Xu Y, et al. Down-regulation of insulin like growth factor 1 involved in Alzheimer's disease via MAPK, Ras, and FoxO signaling pathways. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2022 May 4;2022:8169981.

17. Horvath A, Salman Z, Quinlan P, Wallin A, Svensson J. Patients with Alzheimer's disease have increased levels of insulin-like growth factor-I in serum but not in cerebrospinal fluid. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2020;75(1):289-98.

18. Basu R, Kopchick JJ. GH and IGF1 in cancer therapy resistance. Endocrine-Related Cancer. 2023 Jul 28;30(9):e220414.

19. Yamamoto H, Murphy LJ. Enzymatic conversion of IGF-I to des(1-3)IGF-I in rat serum and tissues: a further potential site of growth hormone regulation of IGF-I action. Journal of Endocrinology. 1995 Jul;146(1):141-8.

20. Guan J, Harris P, Brimble M, Lei Y, Lu J, Yang Y, et al. The role for IGF-1-derived small neuropeptides as a therapeutic target for neurological disorders. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets. 2015 Jun;19(6):785-93.

21. Guan, J.; Gluckman, P.D. IGF-1 derived small neuropeptides and analogues: A novel strategy for the development of pharmaceuticals for neurological conditions. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009, 157, 881-91.

22. Burgos-Ramos E, Martos-Moreno GA, López MG, Herranz R, Aguado-Llera D, Egea J, et al. The N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-I protects against beta-amyloid-induced somatostatin depletion by calcium and glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta modulation. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2009 Apr;109(2):360-70.

23. Kaneko H, Namihira M, Yamamoto S, Numata N, Hyodo K. Oral administration of cyclic glycyl-proline facilitates task learning in a rat stroke model. Behavioural Brain Research. 2022 Jan 24;417:113561.

24. Marinelli L, Fornasari E, Di Stefano A, Turkez H, Arslan ME, Eusepi P, et al. (R)-α-Lipoyl-Gly-l-Pro-l-Glu dimethyl ester as dual acting agent for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Neuropeptides. 2017 Dec;66:52-58.

25. Guan J, Li F, Kang D, Anderson T, Pitcher T, Dalrymple-Alford J, et al. Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP) normalises insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) function: clinical significance in the ageing brain and in age-related neurological conditions. Molecules. 2023 Jan 19;28(3):1021

26. Aguado-Llera D, Martín-Martínez M, García-López MT, Arilla-Ferreiro E, Barrios V Gly-Pro-Glu protects beta-amyloid-induced somatostatin depletion in the rat cortex. Neuroreport. 2004 Aug 26;15(12):1979-82.

27. Silva-Reis SC, Sampaio-Dias IE, Costa VM, Correia XC, Costa-Almeida HF, García-Mera X, et al. Concise overview of glypromate neuropeptide research: from chemistry to pharmacological applications in neurosciences. ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 2023 Feb 15;14(4):554-72.

28. Baker AM, Batchelor DC, Thomas GB, Wen JY, Rafiee M, Lin H, Guan J. Central penetration and stability of N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-I, glycine-proline-glutamate in adult rat. Neuropeptides. 2005 Apr;39(2):81-7.

29. Batchelor DC, Lin H, Wen JY, Keven C, Van Zijl PL, Breier BH, Gluckman PD, Thomas GB. Pharmacokinetics of glycine-proline-glutamate, the N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-1, in rats. Analytical Biochemistry. 2003 Dec 15;323(2):156-63.

30. Alonso De Diego SA, Gutiérrez-Rodríguez M, Pérez de Vega MJ, González-Muñiz R, Herranz R, Martín-Martínez M, Cenarruzabeitia E, Frechilla D, Del Río J, Jimeno ML, García-López MT. The neuroprotective activity of GPE tripeptide analogues does not correlate with glutamate receptor binding affinity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2006 Jul 1;16(13):3396-400.

31. Sara VR, Carlsson-Skwirut C, Bergman T, Jörnvall H, Roberts PJ, Crawford M, Håkansson LN, Civalero I, Nordberg A. Identification of Gly-Pro-Glu (GPE), the aminoterminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor 1 which is truncated in brain, as a novel neuroactive peptide. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1989 Dec 15;165(2):766-71.

32. Vaaga CE, Tovar KR, Westbrook GL. The IGF-derived tripeptide Gly-Pro-Glu is a weak NMDA receptor agonist. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2014 Sep 15;112(6):1241-5.

33. Górecki DC, Beresewicz M, Zabłocka B. Neuroprotective effects of short peptides derived from the Insulin-like growth factor 1. Neurochemistry International. 2007 Dec;51(8):451-8.

34. Misiura M, Miltyk W. Proline-containing peptides-New insight and implications: a review. Biofactors. 2019 Nov;45(6):857-66.

35. Marinelli L, Fornasari E, Di Stefano A, Turkez H, Genovese S, Epifano F, et al. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel analogues of Gly-l-Pro-l-Glu (GPE) as neuroprotective agents. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters. 2019 Jan 15;29(2):194-98.

36. Silva-Reis SC, Costa VM, Correia da Silva D, Pereira DM, Correia XC, Costa-Almeida HF, García-Mera X, Rodríguez-Borges JE, Sampaio-Dias IE. Exploring structural determinants of neuroprotection bias on novel glypromate conjugates with bioactive amines. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024 Mar 5;267:116174.

37. Mohebichamkhorami F, Faizi M, Mahmoudifard M, Hajikarim-Hamedani A, Mohseni SS, Heidari A, Ghane Y, Khoramjouy M, Khayati M, Ghasemi R, et al. Microfluidic synthesis of ultrasmall chitosan/graphene quantum dots particles for intranasal delivery in Alzheimer's disease treatment. Small. 2023 Oct;19(40):e2207626.

38. Gudasheva TA, Koliasnikova KN, Alyaeva AG, Nikolaev SV, Antipova TA, Seredenin SB. Neuroprotective effect of the neuropeptide cycloprolylglycine depends on AMPA- and TrkB-receptor activation. Doklady Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2022 Dec;507(1):264-267.

39. Itoh N, Enomoto A, Nagai T, Takahashi M, Yamada K. Molecular mechanism linking BDNF/TrkB signaling with the NMDA receptor in memory: the role of Girdin in the CNS. Rev Neurosci. 2016 Jul 1;27(5):481-90.

40. Yoshii A, Constantine-Paton M. BDNF induces transport of PSD-95 to dendrites through PI3K-AKT signaling after NMDA receptor activation. Nature Neuroscience. 2007 Jun;10(6):702-11.

41. Sizonenko SV, Sirimanne ES, Williams CE, Gluckman PD. Neuroprotective effects of the N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1, glycine-proline-glutamate, in the immature rat brain after hypoxic-ischemic injury. Brain Research. 2001 Dec 13;922(1):42-50.

42. Ikeda T, Waldbillig RJ, Puro DG. Truncation of IGF-I yields two mitogens for retinal Müller glial cells. Brain Research. 1995 Jul 17;686(1):87-92.

43. Almengló C, Devesa P, Devesa J, Arce VM. GPE promotes the proliferation and migration of mouse embryonic neural stem cells and their progeny in vitro. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017 Jun 16;18(6):1280.

44. Gudasheva TA, Koliasnikova KN, Antipova TA, Seredenin SB. Neuropeptide cycloprolylglycine increases the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neuronal cells. Doklady Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2016 Jul;469(1):273-6.

45. Saura J, Curatolo L, Williams CE, Gatti S, Benatti L, Peeters C, Guan J, Dragunow M, Post C, Faull RL, Gluckman PD, Skinner SJ. Neuroprotective effects of Gly-Pro-Glu, the N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1, in the hippocampus in vitro. Neuroreport. 1999 Jan 18;10(1):161-4.

46. Aguado-Llera D, Canelles S, Fernández-Mendívil C, Frago LM, Argente J, Arilla-Ferreiro E, et al. Improvement in inflammation is associated with the protective effect of Gly-Pro-Glu and cycloprolylglycine against Aβ-induced depletion of the hippocampal somatostatinergic system. Neuropharmacology. 2019 Jun;151:112-26.

47. Povarnina PY, Kolyasnikova KN, Nikolaev SV, Antipova TA, Gudasheva TA. Neuropeptide cycloprolylglycine exhibits neuroprotective activity after systemic administration to rats with modeled incomplete global ischemia and in in vitro modeled glutamate neurotoxicity. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine. 2016 Mar;160(5):653-5.

48. Ai J, Wang H, Chu P, Shopit A, Niu M, Ahmad N, et al. The neuroprotective effects of phosphocreatine on amyloid beta 25-35-induced differentiated neuronal cell death through inhibition of AKT/GSK-3β /Tau/APP/CDK5 pathways in vivo and vitro. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2022 Feb 1;179:416-7.

49. Abbah J, Vacher CM, Goldstein EZ, Li Z, Kundu S, Talbot B, et al. Oxidative stress-induced damage to the developing hippocampus is mediated by GSK3β. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2022 Jun 15;42(24):4812-27.

50. Montminy MR, Bilezikjian LM. Binding of a nuclear protein to the cyclic-AMP response element of the somatostatin gene. Nature. 1987 Jul 9-15;328(6126):175-8.

51. Kimura N, Tomizawa S, Arai KN, Osamura RY, Kimura N. Characterization of 5'-flanking region of rat somatostatin receptor sst2 gene: transcriptional regulatory elements and activation by Pitx1 and estrogen. Endocrinology. 2001 Apr;142(4):1427-41.

52. Michinaga S, Nagata A, Ogami R, Ogawa Y, Hishinuma S. Differential regulation of histamine H1 receptor-mediated ERK phosphorylation by Gq proteins and arrestins. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2023 Jul;213:115595.

53. Carr HS, Chang JT, Frost JA. The PDZ domain protein SYNJ2BP regulates GRK-dependent sst2A phosphorylation and downstream MAPK signaling. Endocrinology. 2021 Feb 1;162(2):bqaa229.

54. Yang W, Zhou X, Ma T. Memory decline and behavioral inflexibility in aged mice are correlated with dysregulation of protein synthesis capacity. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 2019 Sep 4;11:246.

55. Chiotis K, Johansson C, Rodriguez-Vieitez E, Ashton NJ, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, et al. Tracking reactive astrogliosis in autosomal dominant and sporadic Alzheimer's disease with multi-modal PET and plasma GFAP. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2023 Sep 12;18(1):60.

56. Shaw BC, Anders VR, Tinkey RA, Habean ML, Brock OD, Frostino BJ, et al. Immunity impacts cognitive deficits across neurological disorders. Journal of Neurochemistry. 2023 Oct 29.

57. Shi M, Chu F, Zhu F, Zhu J. Peripheral blood amyloid-β involved in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease via impacting on peripheral innate immune cells. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2024 Jan 4;21(1):5.

58. Minelli A, Conte C, Cacciatore I, Cornacchia C, Pinnen F. Molecular mechanism underlying the cerebral effect of Gly-Pro-Glu tripeptide bound to L-dopa in a Parkinson's animal model. Amino Acids. 2012 Sep;43(3):1359-67.

59. Paintlia AS, Paintlia MK, Singh I, Singh AK. IL-4-induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation inhibits NF-kappaB trans activation in central nervous system (CNS) glial cells and protects oligodendrocyte progenitors under neuroinflammatory disease conditions: implication for CNS-demyelinating diseases. The Journal of Immunology. 2006 Apr 1;176(7):4385-98.

60. Pannell M, Szulzewsky F, Matyash V, Wolf SA, Kettenmann H. The subpopulation of microglia sensitive to neurotransmitters/neurohormones is modulated by stimulation with LPS, interferon-γ, and IL-4. Glia. 2014 May;62(5):667-79.

61. Guan J, Li F, Kang D, Anderson T, Pitcher T, Dalrymple-Alford J, et al. Cyclic glycine-proline (cGP) normalises insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) function: clinical significance in the ageing brain and in age-related neurological conditions. Molecules. 2023 Jan 19;28(3):1021.

62. Arora T, Sharma SK. Cyclic glycine-proline improves memory and reduces amyloid plaque load in APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease. 2023 Mar 1;2023:1753791.

63. Turkez H, Cacciatore I, Marinelli L, Fornasari E, Aslan ME, Cadirci K, et al. Glycyl-L-prolyl-L-glutamate pseudotripeptides for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Biomolecules. 2021 Jan 19;11(1):126.

64. Turkez H, Ozdemir Tozlu O, Tatar A, Arslan ME, Cadirci K, Marinelli L, et al. Toxicity of Glycyl-l-Prolyl-l-Glutamate pseudotripeptides: cytotoxic, oxidative, genotoxic, and embryotoxic perspectives. Journal of Toxicology. 2022 Nov 19;2022:3775194.