Commentary

Stroke remains a leading cause of death and long-term disability worldwide, with ischemic stroke representing approximately 85% of all stroke cases [1]. Cerebral ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury significantly exacerbates neuronal damage through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, ferroptosis, and endoplasmic reticulum stress (ERS).

In a recent publication featured in CELLULAR SIGNALLING, Wang et al. explored the neuroprotective role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-D3) in ischemic brain injury, emphasizing its capacity to alleviate ER stress via a vitamin D receptor (VDR)-mediated pathway. Their study demonstrated that 1,25-D3 reduced ER stress markers (p-PERK/PERK and CHOP), activated the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway to inhibit ferroptosis, and decreased lipid peroxidation, thus conferring neuroprotection through modulation of p53 signaling [2].

ER Stress and Stroke

ER stress plays a critical role in the pathophysiology of stroke. Following ischemic stroke, disturbances in the microenvironment—characterized by oxidative stress, intracellular calcium dysregulation, and accumulation of misfolded proteins—precipitate ER stress [3]. Persistent ER stress activates inflammatory pathways and promotes neuronal cell death, contributing significantly to extensive tissue damage.

The unfolded protein response (UPR) represents an adaptive cellular mechanism activated by ER stress to restore ER homeostasis. The UPR is primarily regulated by three ER transmembrane sensors: protein kinase RNA-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α), and activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) [4].

PERK-eIF2α-CHOP pathway

PERK activation leads to phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), resulting in global protein synthesis attenuation, while selectively promoting the translation of stress-responsive proteins such as ATF4 and CHOP. Chronic activation of the PERK/eIF2α pathway and subsequent CHOP upregulation ultimately drive apoptosis. Evidence indicates that activation of the PERK/eIF2α branch post-stroke temporarily inhibits protein synthesis, assisting neuronal recovery from ischemic insults [5]. Sun et al. demonstrated that the proton-sensitive G protein-coupled receptor GPR68 confers neuroprotection by enhancing PERK-eIF2α-mediated UPR activation in ischemic brain tissue [6]. Additionally, Piezo1, a mechanically gated calcium channel, was shown to mitigate ER stress-induced neuronal injury following intracerebral hemorrhage by suppressing PERK-ATF4-CHOP and IRE1 signaling pathways [7].

IRE1α-XBP1 pathway regulation

IRE1α, an ER membrane protein with dual kinase and endoribonuclease activities, plays a pivotal role under stress conditions, including nutrient deprivation and ER stress. Upon activation, IRE1α dissociates from stress granules (SG) via its intrinsic disordered region (IDR), forming aggregates that enhance the efficiency of IRE1α-mediated XBP1 mRNA splicing. This event promotes the expression of UPR-associated genes, including molecular chaperones and protein-folding enzymes, facilitating ER stress relief [8]. Under physiological conditions, nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) factor UPF3B negatively regulates IRE1α activation by binding to its kinase domain, thus preventing excessive ER stress activation [9]. However, stimuli such as the mycotoxin 3-acetyldeoxynivalenol (3-Ac-DON) promote phosphorylation-dependent dissociation of UPF3B from IRE1α, initiating apoptosis [10]. Furthermore, in tumor microenvironments, transmembrane p24 trafficking protein 4 (TMED4) stabilizes IRE1α by inhibiting its ER-associated degradation (ERAD), ensuring IRE1α functionality crucial for regulatory T cell stability [11].

ATF6 signaling and its role in ER homeostasis

ATF6, another critical UPR sensor, binds to the ER stress response element (ERSE), facilitating the transcription of molecular chaperones (e.g., BIP and GRP94) and protein-folding enzymes that promote correct protein folding [12]. Loperamide-induced ER stress, autophagy, and autophagic cell death involve ATF4 upregulation mediated by ATF6 activation [13]. Importantly, ATF6 cooperatively interacts with XBP1 to amplify UPR signaling through a positive feedback loop [14]. The calcium-regulated ER protein GRINA mitigates ER stress during hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing ATF6 ubiquitination, thereby maintaining calcium homeostasis and inhibiting ER-related autophagy [15]. Furthermore, silencing ATF6 decreases reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, preserves mitochondrial membrane potential, and alleviates mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately attenuating ER stress and apoptosis [16].

Notch3 mutations and ER stress

In addition to signaling pathways mediated by the three transmembrane sensors PERK, IRE1, and ATF6, Notch3 functional mutations have been identified as regulators of Rho kinase activity and ER stress. These mutations result in peripheral vascular dysfunction and disturbances in calcium (Ca²?) homeostasis, thereby predisposing individuals to cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) [17]. Recent evidence suggests that Notch3 mutations contribute to small artery vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) damage through ER stress induction and associated inflammatory pathways. Specifically, NOTCH3 mutations influence ER stress, interleukin-6 (IL-6), intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) expression, and the eNOS/sGC/cGMP signaling cascade [18]. However, the roles of local inflammatory and immune responses mediated by NOTCH3 mutations in stroke warrant further investigation. Intermittent fasting has emerged as a beneficial intervention for improving outcomes in stroke and Alzheimer's disease. Notably, 2-deoxyglucose, a glucose analog, mimics fasting conditions by alleviating ER stress and enhancing Bdnf transcriptional activity, thereby improving cognitive function, protein homeostasis, and recovery post-stroke [19].

Calcium homeostasis, ER stress, and apoptosis

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is crucial for maintaining cellular calcium (Ca²?) homeostasis and facilitating proper protein folding. ER functionality depends on tightly regulated Ca²? balance, as Ca²? is essential for ER-resident chaperones such as BiP/Grp78, calreticulin (CRT), and calnexin (CNX), which are critical for protein folding and quality control. Disruptions in ER Ca²? balance—whether due to excessive Ca²? depletion or overload—trigger ER stress, initiating the unfolded protein response (UPR). This response is pivotal in determining cell fate under pathological conditions, including stroke.

Ca²? homeostasis in the ER is maintained by the sarco/ER Ca²?-ATPase (SERCA) pump, responsible for importing Ca²?, and various Ca²? release channels. Reduced ER Ca²? levels inactivate Ca²?-dependent chaperones, leading to protein misfolding and accumulation of unfolded proteins within the ER lumen, thereby activating ER stress and the UPR. Impaired SERCA activity or excessive Ca²? release mediated by InsP3R can significantly lower ER Ca²? levels, further exacerbating protein misfolding and stress. Conversely, ER Ca²? overload disrupts Ca²? transfer at mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), resulting in mitochondrial Ca²? overload, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. If ER stress persists and the UPR cannot restore equilibrium, pro-apoptotic pathways involving Ca²? signaling are activated. Specifically, Ca²?-dependent activation of calpain and caspase-12, along with PERK-ATF4-CHOP signaling, promotes apoptosis by downregulating anti-apoptotic BCL-2 and upregulating pro-apoptotic BAX, aggravating cerebral ischemia-reperfusion-induced tissue damage [20].

Mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs)

Physical connections between the ER and mitochondria, termed mitochondria-associated ER membranes (MAMs), have recently gained attention. MAM integrity and function are essential for cellular homeostasis. Studies have revealed that mitochondrial mitofusin 2 (MFN2) and its splice variant ERMIT2 act as structural tethers connecting mitochondria to the ER. ERMIT2 and ERMIN2, splice variants of MFN2, regulate ER morphology and ameliorate ER stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in hepatic tissues [21]. Additionally, the EMC2-SLC25A46-Mic19 axis has been demonstrated to modulate ER-mitochondrial interactions, reduce ER-mitochondrial damage, and mitigate conditions such as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis, highlighting a critical role for ER-mitochondrial crosstalk in maintaining cellular health and preventing disease progression [22].

Ferroptosis and Stroke

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent, regulated form of programmed cell death characterized primarily by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products. Excessive intracellular iron, caused by disrupted iron uptake, transport, storage, and utilization, exacerbates lipid peroxidation, particularly affecting polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in cell membranes. This process results in membrane damage, cellular dysfunction, and cell death.

Following ischemic stroke, cell membrane PUFAs such as arachidonic acid undergo peroxidation mediated by enzymes like lipoxygenase (LOX) and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR), producing toxic lipid peroxides including 4-hydroxynonenal and malondialdehyde. Concurrently, intracellular glutathione (GSH) depletion significantly impairs glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity, preventing effective suppression of lipid peroxidation and exacerbating neuronal damage.

Figure 1. Overview of the mechanisms of endoplasmic reticulum stress and ischemic stroke. eIF2α: Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2α; ATF6: Activating Transcription Factor 6; ATF4: Activating Transcription Factor 4; UPR: Unfolded Protein Response; IRE1α: Inositol-Requiring Enzyme 1 α; PERK: Protein Kinase RNA-like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase; CHOP: C/EBP Homologous Protein; XBP1: X-box Binding Protein 1.

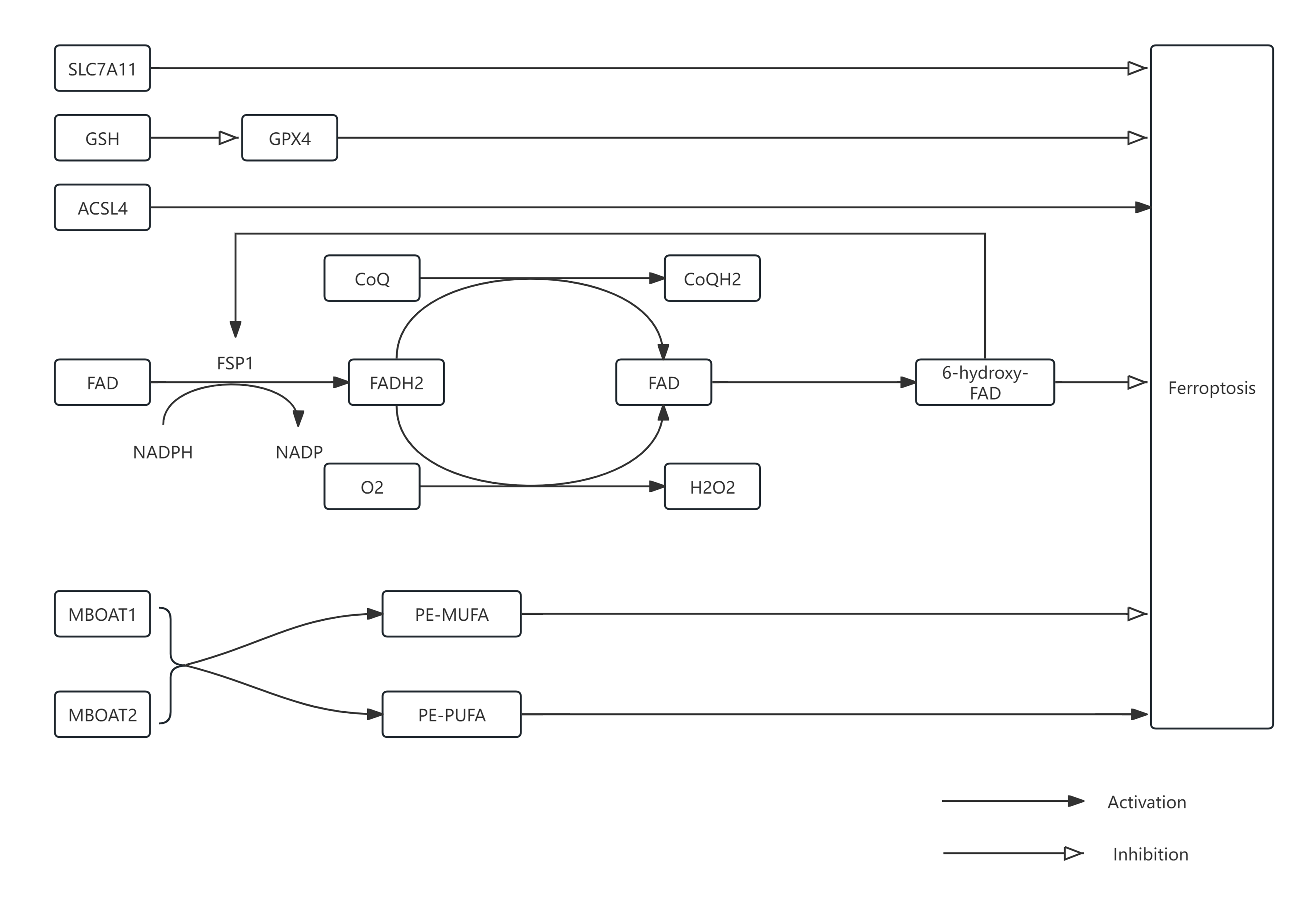

Figure 2. Overview of the mechanisms of ferroptosis and ischemic stroke. SLC7A11: Solute Carrier Family 7 Member A11; GSH: Glutathione; ACSL4: Acyl-CoA Synthetase Long-chain Family Member 4; FAD: Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide; FSP1: Ferroptosis Suppressor Protein 1; NADPH: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate; NADP: Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate; FADH2: Flavin Adenine Dinucleotide Reduced; CoQ: Coenzyme Q; CoQH2: Reduced Coenzyme Q; GPX4: Glutathione Peroxidase 4; MBOAT: Membrane-bound O-acyltransferase 1; MBOAT2: Membrane-bound O-acyltransferase 2.

Recent studies have identified various natural compounds capable of inhibiting ferroptosis and improving neurological outcomes post-stroke. For instance, Rehmannioside A, derived from traditional Chinese medicine, was shown by Chen Fu et al. to suppress ferroptosis and cognitive impairment following ischemic stroke via activation of the PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 and SLC7A11/GPX4 pathways [23]. Similarly, Xue Bai et al. demonstrated the protective effect of ferroptosis inhibition in both ischemic and hemorrhagic strokes through the activation of the PPARγ/AKT/GPX4 signaling pathway [24]. Other bioactive compounds, including Kaempferol, Rhein, and Loureirin C, enhance GPX4 expression and reduce neuronal death following ischemia-reperfusion injury [25-27]. Additionally, Quercetin, Gastrodin, and Baicalein effectively inhibit ferroptosis by upregulating GPX4 and downregulating ACSL4 [28-30].

GPX4-independent ferroptosis regulation: The role of FSP1

Mechanistically, ferroptosis inhibition primarily involves GPX4-dependent pathways and GPX4-independent pathways mediated by ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1). FSP1, a distinct ferroptosis inhibitor independent of glutathione, functions as a homodimer via its C-terminal domain (CTD) [31]. Loss of the CTD prevents dimer formation and disrupts ferroptosis inhibition. FSP1 catalyzes the reduction of ubiquinone (CoQ) to ubiquinol (CoQH2) using NAD(P)H as an electron donor, providing antioxidant protection. Under aerobic conditions, FSP1 also reduces oxygen to hydrogen peroxide (H?O?), again utilizing NAD(P)H. Furthermore, FSP1-mediated hydroxylation of FAD to 6-hydroxy-FAD enhances its catalytic and antioxidant activities [32]. Recent findings by Man-Ru Liu et al. demonstrated that Sorafenib induces ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the ERK-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of FSP1 [33]. In ovarian cancer, ACSL1 has been shown to enhance ferroptosis resistance by promoting FSP1 myristoylation, augmenting antioxidant capacity [34]. Emerging evidence indicates that enhancing FSP1 expression can mitigate ferroptosis-related damage following subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury [35]. However, research on the interactions between FSP1 and ferroptosis in neurological disorders remains limited and warrants further exploration.

Emerging ferroptosis regulators: MBOATs and hormonal signaling

Notably, recent studies have identified novel mechanisms of ferroptosis inhibition involving the membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOATs), specifically MBOAT1 and MBOAT2, which function independently of GPX4 and FSP1 pathways [36]. In cells deficient for both GPX4 and FSP1, MBOAT2 maintains effective inhibition of ferroptosis, underscoring its distinct mechanism. MBOAT enzymes catalyze the transfer of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) such as oleic acid to lysophosphatidylethanolamine (lyso-PE), promoting phospholipid remodeling [36,37]. This activity increases PE-MUFA levels and decreases PE-PUFA content, thereby reducing susceptibility to lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, estrogen receptors (ER) and androgen receptors (AR) transcriptionally regulate MBOAT1 and MBOAT2, respectively, by binding to their gene promoters [38, 39]. The MBOAT-mediated phospholipid remodeling pathway thus represents a promising, albeit relatively unexplored, therapeutic target for neurological diseases characterized by ferroptosis.

Multi-target Therapeutic Strategies: The Neuroprotective Role of Vitamin D

Vitamin D has demonstrated substantial potential as a therapeutic agent for ischemic stroke, exerting neuroprotective effects through multiple pathways. It mitigates endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress by reducing levels of phosphorylated PERK (p-PERK), PERK, and CHOP, while concurrently activating the Nrf2/GPX4 signaling axis to inhibit ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation [2]. Beyond its neuroprotective role, clinical studies have validated vitamin D's broad therapeutic efficacy and safety profile. For instance, vitamin D supplementation significantly reduces the recurrence of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and alleviates depressive symptoms in elderly individuals aged 60 and above [40,41]. Furthermore, maternal high-dose vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy positively influences early neurodevelopmental outcomes in children [42] and improves insulin sensitivity in prediabetic patients, potentially delaying diabetes onset [43].

Recent preclinical studies have further elucidated vitamin D's multifaceted roles in cerebrovascular and neuroinflammatory conditions. Pan Cui et al. demonstrated that microglia and macrophages in vitamin D receptor (VDR)-deficient mice exhibit a pronounced pro-inflammatory phenotype post-stroke, characterized by elevated secretion of TNF-α and IFN-γ. These cytokines subsequently augment CXCL10 release, exacerbating neuroinflammation and stroke-induced brain injury [44]. Jiaxin Liu and colleagues reported that vitamin D promotes macrophage-mediated hematoma clearance in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage, enhancing tissue repair and improving clinical outcomes [45]. Additionally, research by Tetsuro Kimura et al. identified VDR expression on intracranial vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, highlighting vitamin D's capacity to prevent aneurysm rupture [46]. Clinical trials published in prominent journals like BMJ further confirm vitamin D’s cardiovascular benefits, reducing the incidence of major cardiovascular events [47].

Vitamin D receptor (VDR) signaling in endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis

Activation of the vitamin D receptor (VDR) by vitamin D3 critically modulates essential pathways involved in endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, contributing significantly to its neuroprotective effects. Specifically, vitamin D3 inhibits the phosphorylation of protein kinase RNA-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) and the subsequent expression of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP) through VDR activation [2]. Mechanistically, activated VDR may directly bind to the vitamin D response element (VDRE) located within the promoter region of the PERK gene, repressing its transcriptional activity. Alternatively, VDR activation may recruit transcriptional co-repressors, such as histone deacetylases, leading to suppressed PERK expression. Inhibition of PERK signaling consequently reduces phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α), decreasing activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) and CHOP levels, ultimately attenuating ER stress-induced apoptosis and mitigating neuronal injury during cerebral ischemia-reperfusion [48].

Beyond the PERK pathway, vitamin D3 and VDR signaling also potentially regulate the inositol-requiring enzyme 1α (IRE1α)-X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) pathway through indirect mechanisms. For instance, VDR activation could modulate IRE1α activity by regulating associated cofactors or modifying enzymatic activities relevant to IRE1α function. Additionally, vitamin D3 might transiently elevate ER unfolded protein load by inhibiting specific components of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) machinery, such as Hrd1 or gp78, indirectly activating IRE1α and promoting adaptive splicing of XBP1. Such compensatory activation of the IRE1α-XBP1 pathway enhances the unfolded protein response (UPR), thereby improving cellular resilience to ER stress conditions [48].

Moreover, VDR activation inhibits signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) binding to the activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) promoter, resulting in reduced ATF6 mRNA and protein expression and diminished downstream ER stress signaling [49]. Supporting evidence from recent studies indicates that vitamin D (1,25D?) directly ameliorates ER stress via VDR-dependent suppression of ATF6 in mammary epithelial cells [50].

Regarding the interaction between vitamin D signaling and ferroptosis modulators such as membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOATs) or ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1), direct experimental data are currently limited. Nevertheless, vitamin D significantly enhances cellular antioxidant capacity via activation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent pathways [51,52]. Such antioxidant enhancement may indirectly support FSP1 functionality by promoting its stability or expression, thereby conferring protective effects against ferroptosis. Additionally, given the transcriptional regulatory capacity of VDR [53], vitamin D signaling could potentially influence the expression or functional regulation of enzymes such as MBOAT1 and MBOAT2, known to be transcriptionally regulated by nuclear hormone receptors including estrogen and androgen receptors [36]. However, explicit experimental confirmation demonstrating direct vitamin D-mediated regulation of MBOATs or FSP1 is lacking. Future research to clarify these mechanisms is crucial, as elucidating such interactions could substantially enhance our understanding of the crosstalk between vitamin D signaling and ferroptosis, ultimately informing therapeutic strategies for neuroprotection.

Modulation of multiple cell death pathways by vitamin D

Mechanistically, vitamin D also modulates multiple cell death pathways beyond ER stress and ferroptosis. In cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury models, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-VitD3) inhibits NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis by activating the antioxidant Nrf2/HO-1 pathway [54]. In septic encephalopathy, vitamin D attenuates histone-induced pyroptosis and ferroptosis, reducing associated neurological deficits [55]. Moreover, vitamin D administration significantly reduces apoptosis and hepatic injury induced by type 2 diabetes [56]. Studies by Aimei Li et al. indicate that autophagic dysfunction observed in diabetic nephropathy models lacking VDR may be linked to disrupted Ca²?/CAMKK2/AMPK signaling, highlighting vitamin D’s regulatory role in autophagy and inflammation [57].

Despite substantial evidence supporting the beneficial role of vitamin D in alleviating ER stress and ferroptosis in ischemic stroke, critical gaps remain in the current understanding. For instance, it remains unclear whether the modulatory effects of vitamin D on ER stress pathways are influenced by cell type, stroke severity, or the particular experimental stroke model employed. Differences in VDR expression levels among neuronal and glial cells could lead to heterogeneous responses to vitamin D treatment. Moreover, the activation patterns of ER stress pathways may differ significantly between acute and chronic ischemic models, and the therapeutic outcomes of vitamin D administration could be profoundly impacted by variations in dosing and timing. Another pivotal unresolved issue pertains to distinguishing direct versus indirect actions of vitamin D on ferroptosis regulators such as ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1) and membrane-bound O-acyltransferases (MBOATs). Addressing these knowledge gaps necessitates comprehensive comparative analyses involving diverse cellular and animal stroke models, complemented by rigorous clinical trials. Such research endeavors will significantly enhance our mechanistic insights into vitamin D signaling and optimize its therapeutic potential for stroke management.

Although preclinical findings underscore the promising therapeutic potential of vitamin D in mitigating ER stress and ferroptosis in stroke, several translational limitations must be explicitly recognized. Most current data originate from preclinical research involving cellular experiments and animal stroke models. While these studies are indispensable, they cannot entirely replicate the complexity of human stroke pathology, particularly the inter-individual variations in patient characteristics, comorbidities, and timing of therapeutic intervention. Moreover, the translational relevance of mechanisms observed in preclinical models requires validation in human subjects. Consequently, rigorous clinical trials are essential to translate these preclinical insights into clinically effective strategies. Future clinical investigations should strive to validate therapeutic efficacy, establish optimal dosing regimens, determine precise therapeutic windows, and ensure the long-term safety and bioavailability of vitamin D supplementation in diverse stroke populations. Resolving these translational challenges is paramount for fully harnessing the therapeutic capabilities of vitamin D in clinical stroke management.

Conclusion

Collectively, these findings underscore the versatility of vitamin D signaling through its receptor as a critical regulatory nexus interconnecting ER stress, ferroptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress pathways. Given the multifaceted and complex pathology of stroke, single-target pharmacological approaches often yield limited therapeutic efficacy. Thus, drug development paradigms are increasingly shifting toward multi-target strategies capable of simultaneously modulating multiple pathological mechanisms [58-60]. Vitamin D exemplifies such a multifunctional therapeutic candidate; however, translating these promising preclinical findings into clinical practice remains challenging. Important clinical questions, including determining optimal dosing regimens, timing, administration routes, and enhancing bioavailability, must be addressed to maximize therapeutic benefit in stroke patients. Future research directions should specifically investigate combination therapies—for example, combining vitamin D with ferroptosis regulators such as FSP1 inducers, or modulators of ER stress pathways—in diverse cellular and animal stroke models. Clarifying cell type-specific responses, the direct versus indirect mechanisms of vitamin D action, and validating efficacy across various stroke severities will be crucial. Ultimately, rigorous translational research and well-designed clinical trials are essential to fully exploit the therapeutic potential of vitamin D-based multi-target strategies, aiming to improve patient outcomes and quality of life following stroke.

Author Contributions: Credit

Yifeng zhang; Writing – original draft; Conceptualization; Investigation; Visualization

Xiaolu wang: Writing – original draft; Conceptualization; Investigation

Zimeng chen: Writing – original draft; Conceptualization; Investigation

Yanqiang wang: Writing – review and editing; Conceptualization; Investigation; Visualization

Funding

This work was supported by the Yuan Du Scholars Program and the Affiliated Hospital of Shandong Second Medical University Horizontal Project (WYFYKY-HX202307, WYFYKY-HX202201), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870943), the Health China Bu Chang ZhiYuan Public welfare projects for heart and brain health under Grant (No. HIGHER2023072), and the Shandong Second Medical University Affiliated Hospital Technology Development Project (2023FYM001, 2023FYM006).

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Editorial teachers and reviewers. And thank Editorial teachers and reviewers.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

2. Song T, Li J, Xia Y, Hou S, Zhang X, Wang Y. 1,25-D3 ameliorates ischemic brain injury by alleviating endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis: Involvement of vitamin D receptor and p53 signaling. Cell Signal. 2024;122:111331.

3. Huang G, Zang J, He L, Zhu H, Huang J, Yuan Z, et al. Bioactive Nanoenzyme Reverses Oxidative Damage and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Neurons under Ischemic Stroke. ACS Nano. 2022;16(1):431-52.

4. Ghemrawi R, Khair M. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(17):6127.

5. Wang YC, Li X, Shen Y, Lyu J, Sheng H, Paschen W, et al. PERK (Protein Kinase RNA-Like ER Kinase) Branch of the Unfolded Protein Response Confers Neuroprotection in Ischemic Stroke by Suppressing Protein Synthesis. Stroke. 2020;51(5):1570-7.

6. Sun W, Tiwari V, Davis G, Zhou G, Jonchhe S, Zha X. Time-Dependent Potentiation of the PERK Branch of UPR by GPR68 Offers Protection in Brain Ischemia. Stroke. 2024;55(10):2510-21.

7. Qu J, Zong HF, Shan Y, Zhang SC, Guan WP, Yang Y, et al. Piezo1 suppression reduces demyelination after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neural Regen Res. 2023;18(8):1750-6.

8. Salvagno C, Mandula JK, Rodriguez PC, Cubillos-Ruiz JR. Decoding endoplasmic reticulum stress signals in cancer cells and antitumor immunity. Trends Cancer. 2022;8(11):930-43.

9. Sun X, Lin R, Lu X, Wu Z, Qi X, Jiang T, et al. UPF3B modulates endoplasmic reticulum stress through interaction with inositol-requiring enzyme-1α. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(8):587.

10. Jia H, Liu N, Zhang Y, Wang C, Yang Y, Wu Z. 3-Acetyldeoxynivalenol induces cell death through endoplasmic reticulum stress in mouse liver. Environ Pollut. 2021;286:117238.

11. Jiang Z, Wang H, Wang X, Duo H, Tao Y, Li J, et al. TMED4 facilitates regulatory T cell suppressive function via ROS homeostasis in tumor and autoimmune mouse models. J Clin Invest. 2024;135(1):e179874.

12. Spaan CN, Smit WL, van Lidth de Jeude JF, Meijer BJ, Muncan V, van den Brink GR, et al. Expression of UPR effector proteins ATF6 and XBP1 reduce colorectal cancer cell proliferation and stemness by activating PERK signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(7):490.

13. Zielke S, Kardo S, Zein L, Mari M, Covarrubias-Pinto A, Kinzler MN, et al. ATF4 links ER stress with reticulophagy in glioblastoma cells. Autophagy. 2021;17(9):2432-48.

14. Jain K, Tyagi T, Du J, Hu X, Patell K, Martin KA, et al. Unfolded Protein Response Differentially Modulates the Platelet Phenotype. Circ Res. 2022;131(4):290-307.

15. Yu H, Wang C, Qian B, Yin B, Ke S, Bai M, et al. GRINA alleviates hepatic ischemia‒reperfusion injury-induced apoptosis and ER-phagy by enhancing HRD1-mediated ATF6 ubiquitination. J Hepatol. 2025 Jan 22:S0168-8278(25)00019-4.

16. Zhang S, Zhao X, Hao J, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. The role of ATF6 in Cr(VI)-induced apoptosis in DF-1 cells. J Hazard Mater. 2021;410:124607.

17. Neves KB, Morris HE, Alves-Lopes R, Muir KW, Moreton F, Delles C, et al. Peripheral arteriopathy caused by Notch3 gain-of-function mutation involves ER and oxidative stress and blunting of NO/sGC/cGMP pathway. Clin Sci (Lond). 2021;135(6):753-73.

18. Panahi M, Hase Y, Gallart-Palau X, Mitra S, Watanabe A, Low RC, et al. ER stress induced immunopathology involving complement in CADASIL: implications for therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2023;11(1):76.

19. Kumar A, Karuppagounder SS, Chen Y, Corona C, Kawaguchi R, Cheng Y, et al. 2-Deoxyglucose drives plasticity via an adaptive ER stress-ATF4 pathway and elicits stroke recovery and Alzheimer's resilience. Neuron. 2023;111(18):2831-46.e10.

20. Wu Y, Fan X, Chen S, Deng L, Jiang L, Yang S, et al. Geraniol-Mediated Suppression of Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Protects against Cerebral Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury via the PERK-ATF4-CHOP Pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24(1):544.

21. Naón D, Hernández-Alvarez MI, Shinjo S, Wieczor M, Ivanova S, Martins de Brito O, et al. Splice variants of mitofusin 2 shape the endoplasmic reticulum and tether it to mitochondria. Science. 2023;380(6651):eadh9351.

22. Dong J, Chen L, Ye F, Tang J, Liu B, Lin J, et al. Mic19 depletion impairs endoplasmic reticulum-mitochondrial contacts and mitochondrial lipid metabolism and triggers liver disease. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):168.

23. Fu C, Wu Y, Liu S, Luo C, Lu Y, Liu M, et al. Rehmannioside A improves cognitive impairment and alleviates ferroptosis via activating PI3K/AKT/Nrf2 and SLC7A11/GPX4 signaling pathway after ischemia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2022;289:115021.

24. Bai X, Zheng E, Tong L, Liu Y, Li X, Yang H, et al. Angong Niuhuang Wan inhibit ferroptosis on ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke by activating PPARγ/AKT/GPX4 pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;321:117438.

25. Yuan Y, Zhai Y, Chen J, Xu X, Wang H. Kaempferol Ameliorates Oxygen-Glucose Deprivation/Reoxygenation-Induced Neuronal Ferroptosis by Activating Nrf2/SLC7A11/GPX4 Axis. Biomolecules. 2021;11(7):923.

26. Liu H, Zhang TA, Zhang WY, Huang SR, Hu Y, Sun J. Rhein attenuates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury via inhibition of ferroptosis through NRF2/SLC7A11/GPX4 pathway. Exp Neurol. 2023;369:114541.

27. Liu Y, Mi Y, Wang Y, Meng Q, Xu L, Liu Y, et al. Loureirin C inhibits ferroptosis after cerebral ischemia reperfusion through regulation of the Nrf2 pathway in mice. Phytomedicine. 2023;113:154729.

28. Li M, Meng Z, Yu S, Li J, Wang Y, Yang W, et al. Baicalein ameliorates cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via regulating GPX4/ACSL4/ACSL3 axis. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;366:110137.

29. Gong C, Fu X, Ma Q, He M, Zhu X, Liu L, et al. Gastrodin: Modulating the xCT/GPX4 and ACSL4/LPCAT3 pathways to inhibit ferroptosis after ischemic stroke. Phytomedicine. 2025;136:156331.

30. Peng C, Ai Q, Zhao F, Li H, Sun Y, Tang K, et al. Quercetin attenuates cerebral ischemic injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;963:176264.

31. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693-8.

32. Lv Y, Liang C, Sun Q, Zhu J, Xu H, Li X, et al. Structural insights into FSP1 catalysis and ferroptosis inhibition. Nat Commun. 2023;14(1):5933.

33. Liu MR, Shi C, Song QY, Kang MJ, Jiang X, Liu H, et al. Sorafenib induces ferroptosis by promoting TRIM54-mediated FSP1 ubiquitination and degradation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7(10):e0246.

34. Zhang Q, Li N, Deng L, Jiang X, Zhang Y, Lee LTO, et al. ACSL1-induced ferroptosis and platinum resistance in ovarian cancer by increasing FSP1 N-myristylation and stability. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):83.

35. Chen J, Shi Z, Zhang C, Xiong K, Zhao W, Wang Y. Oroxin A alleviates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage by regulating ferroptosis and neuroinflammation. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21(1):116.

36. Liang D, Feng Y, Zandkarimi F, Wang H, Zhang Z, Kim J, et al. Ferroptosis surveillance independent of GPX4 and differentially regulated by sex hormones. Cell. 2023;186(13):2748-64.e22.

37. Rodencal J, Kim N, He A, Li VL, Lange M, He J, et al. Sensitization of cancer cells to ferroptosis coincident with cell cycle arrest. Cell Chem Biol. 2024;31(2):234-48.e13.

38. Belavgeni A, Tonnus W, Linkermann A. Cancer cells evade ferroptosis: sex hormone-driven membrane-bound O-acyltransferase domain-containing 1 and 2 (MBOAT1/2) expression. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):336.

39. Sex Hormone Signaling Suppresses Ferroptosis via Phospholipid Remodeling. Cancer Discov. 2023;13(8):1759.

40. Jeong SH, Kim JS, Kim HJ, Choi JY, Koo JW, Choi KD, et al. Prevention of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo with vitamin D supplementation: A randomized trial. Neurology. 2020;95(9):e1117-e25.

41. Alavi NM, Khademalhoseini S, Vakili Z, Assarian F. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on depression in elderly patients: A randomized clinical trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(5):2065-70.

42. Rodgers MD, Mead MJ, McWhorter CA, Ebeling MD, Shary JR, Newton DA, et al. Vitamin D and Child Neurodevelopment-A Post Hoc Analysis. Nutrients. 2023;15(19):4250.

43. Niroomand M, Fotouhi A, Irannejad N, Hosseinpanah F. Does high-dose vitamin D supplementation impact insulin resistance and risk of development of diabetes in patients with pre-diabetes? A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;148:1-9.

44. Cui P, Lu W, Wang J, Wang F, Zhang X, Hou X, et al. Microglia/macrophages require vitamin D signaling to restrain neuroinflammation and brain injury in a murine ischemic stroke model. J Neuroinflammation. 2023;20(1):63.

45. Liu J, Li N, Zhu Z, Kiang KM, Ng ACK, Dong CM, et al. Vitamin D Enhances Hematoma Clearance and Neurologic Recovery in Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Stroke. 2022;53(6):2058-68.

46. Kimura T, Rahmani R, Miyamoto T, Kamio Y, Kudo D, Sato H, et al. Vitamin D deficiency promotes intracranial aneurysm rupture. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2024;44(7):1174-83.

47. Thompson B, Waterhouse M, English DR, McLeod DS, Armstrong BK, Baxter C, et al. Vitamin D supplementation and major cardiovascular events: D-Health randomised controlled trial. Bmj. 2023;381:e075230.

48. Erzurumlu Y, Aydogdu E, Dogan HK, Catakli D, Muhammed MT, Buyuksandic B. 1,25(OH)(2) D(3) induced vitamin D receptor signaling negatively regulates endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD) and androgen receptor signaling in human prostate cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2023;103:110577.

49. Wei J, Zhan J, Ji H, Xu Y, Xu Q, Zhu X, et al. Fibroblast Upregulation of Vitamin D Receptor Represents a Self-Protective Response to Limit Fibroblast Proliferation and Activation during Pulmonary Fibrosis. Antioxidants (Basel). 2023;12(8):1634.

50. Wen G, Eder K, Ringseis R. 1,25-hydroxyvitamin D3 decreases endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced inflammatory response in mammary epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2020;15(2):e0228945.

51. Xu P, Lin B, Deng X, Huang K, Zhang Y, Wang N. VDR activation attenuates osteoblastic ferroptosis and senescence by stimulating the Nrf2/GPX4 pathway in age-related osteoporosis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;193(Pt 2):720-35.

52. Li L, Li WJ, Zheng XR, Liu QL, Du Q, Lai YJ, et al. Eriodictyol ameliorates cognitive dysfunction in APP/PS1 mice by inhibiting ferroptosis via vitamin D receptor-mediated Nrf2 activation. Mol Med. 2022;28(1):11.

53. Carlberg C, Muñoz A. An update on vitamin D signaling and cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;79:217-30.

54. Qiao J, Ma H, Chen M, Bai J. Vitamin D alleviates neuronal injury in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via enhancing the Nrf2/HO-1 antioxidant pathway to counteract NLRP3-mediated pyroptosis. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2023;82(8):722-33.

55. Sun Y, Pu Z, Zhao H, Deng Y, Zhang J, Li S, et al. Vitamin D can mitigate sepsis-associated neurodegeneration by inhibiting exogenous histone-induced pyroptosis and ferroptosis: Implications for brain protection and cognitive preservation. Brain Behav Immun. 2025;124:40-54.

56. Hamouda HA, Mansour SM, Elyamany MF. Vitamin D Combined with Pioglitazone Mitigates Type-2 Diabetes-induced Hepatic Injury Through Targeting Inflammation, Apoptosis, and Oxidative Stress. Inflammation. 2022;45(1):156-71

57. Li A, Yi B, Han H, Yang S, Hu Z, Zheng L, et al. Vitamin D-VDR (vitamin D receptor) regulates defective autophagy in renal tubular epithelial cell in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice via the AMPK pathway. Autophagy. 2022;18(4):877-90.

58. Turgutalp B, Kizil C. Multi-target drugs for Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2024;45(7):628-38.

59. Xu W, Ye C, Qing X, Liu S, Lv X, Wang W, et al. Multi-target tyrosine kinase inhibitor nanoparticle delivery systems for cancer therapy. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16:100358.

60. Rodríguez-Soacha DA, Scheiner M, Decker M. Multi-target-directed-ligands acting as enzyme inhibitors and receptor ligands. Eur J Med Chem. 2019;180:690-706.