Keywords

Arnold Chiari Malformation, Ventricle-peritoneal shunt, Neuropathy, Ureteral obstruction, CSF pseudocyst, Microscopic hematuria, Hydronephrosis

Case Presentation

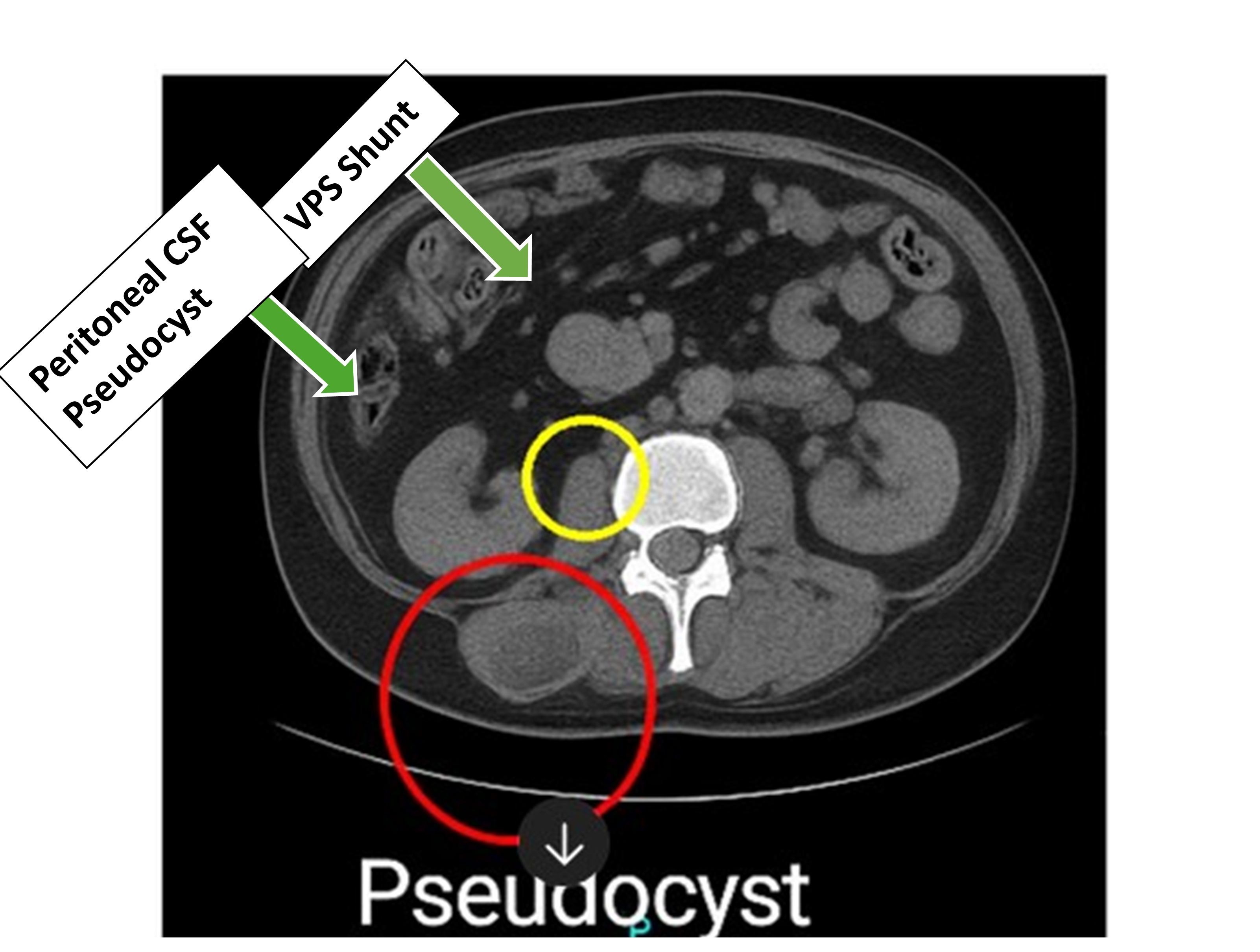

We report a case of a 51-year-old male presented to the neurology clinic with intermittent dizziness, blurred vision, chronic left sided weakness and numbness. Further workup by brain MRI unearthed increased intracranial pressure secondary to impaired CSF drainage. He was previously diagnosed with Arnold Chiari type I malformation for which ventricle-peritoneal shunt (VPS) was performed in 1994 (Figure 1). Following this, ensuing imaging or evaluation for shunt revision was never attempted. During routine follow up, he complained of abdominal pain and subsequent work up revealed microscopic hematuria. A CT scan of abdomen and pelvis unearthed a peritoneal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pseudocyst which is compressing the ureter and causing hydronephrosis (Figure 2). The probable causes of peritoneal pseudocyst including infection and adhesions was thoroughly investigated with appropriate investigations. Subsequently, he was referred for surgical resection of abdominal pseudocyst. During surgical exploration, a large peritoneal CSF containing pseudocyst with adhesions was identified. Furthermore, the pseudocyst was irregular in shape, lacked proper epithelial lining and had an ill-defined border. Complete resection of CSF pseudocyst was performed and VPS was removed and repositioned in another abdominal quadrant. Following surgery, patient signs and symptoms were completely resolved. He was advised to have a regular follow up of VPS periodically to detect shunt malfunction and associated complications.

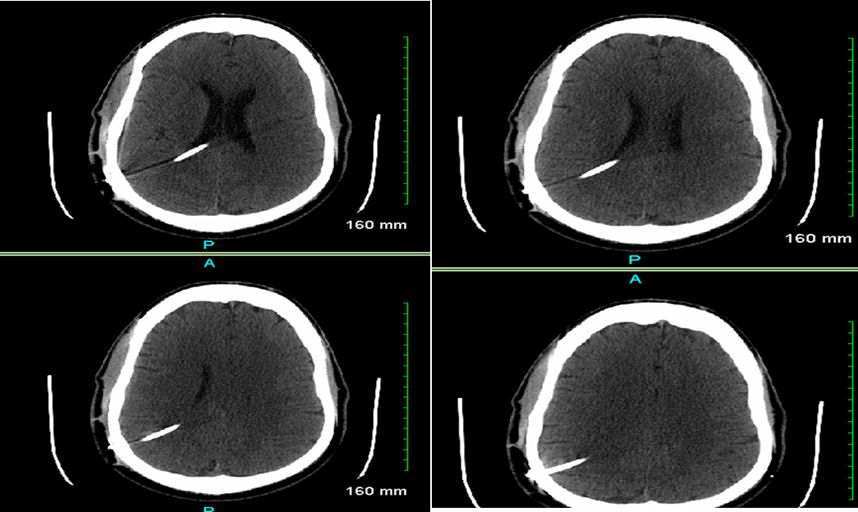

Figure 1. CT head with and without contrast. A right posterior parietal approach shunt extending though the lateral ventricle with its tip at the posterior midline in the upper third ventricle. Ventricular system appears to be decompressed. The intracranial and extracranial shunt tube appears to be normal.

Figure 2. CT abdomen and pelvis. Imaging of the pelvis shows loculated fluid collection in the right lower quadrant. There are some calcifications in soft tissues in the right lower quadrant.

Discussion

There is an excess buildup of CSF in clinical disorders such as hydrocephalus, tumors, arachnoid cyst or myelomeningocele due to thwarting of CSF circulation in the brain [1]. Accordingly, increased intracranial pressure due to crippled CSF drainage can lead to symptoms ranging from chronic headaches, learning difficulties, visual disturbances, urinary retention, dementia, gait disturbances and mental retardation [1,2]. In such clinical scenarios, a VPS is a best therapeutic option to drain and divert the excess CSF from the cerebral ventricles to the abdominal cavity, atrial cavity or pleural cavity [1]. In patient with VPS, the risk of developing abdominal pseudocyst is heightened due to stymied CSF absorption in the peritoneal cavity secondary to infections, adhesions, subclinical peritonitis, obstruction, and multiple shunt revisions [3]. Furthermore, foreign body reaction stimulating localized adhesions, inflammation and particle like proteins in the CSF are also speculated to be the possible mechanisms for CSF pseudocyst inception [4]. Moreover, shunt failure might happen due to proximal malfunction, distal failure, catheter occlusion and infection, thus inciting impaired CSF drainage and fluid accumulation in the gut [5].

Peritoneal CSF pseudocysts are broadly classified into three types according to their pathophysiological states, actively infected, sterile with active systemic inflammation, and sterile with no signs of systemic inflammation [6]. The incidence of abdominal pseudocyst is approximately 0.33–6.8% in patients with VPS shunt [7]. When such a clinical scenario transpires, the patient can present with abdominal pain, abdominal mass, nausea, vomiting, and headache. Very rarely, the CSF pseudocyst enlarges so that it can obstruct the ureter causing hydronephrosis and renal failure as happened in our patient [8]. Ultrasonography and CT (Computer Tomography) scan abdomen is usually diagnostic for diagnosis of peritoneal CSF pseudocyst [9]. Surgical therapy is the mainstay of management of peritoneal CSF pseudocyst. This entails redirection of shunt into different abdominal quadrant, atrial cavity or pleural cavity or external surface [10–12]. All the patients should be treated with empirical antibiotics irrespective of pseudocyst culture results, as subclinical infection can be commonly responsible for instigating recurrent CSF pseudocysts [6].

In our patient, CSF pseudocyst was surgically excised and shunt was repositioned to different abdominal quadrant. This resulted in significant relief of his signs and symptoms. Most cases of peritoneal pseudocyst occur within 6 months of previous abdominal surgery secondary to low grade infection, peritonitis or immune mediated reaction [11,13].

The presence of inflammatory markers requires external distal tubing with peritoneal reimplantation while absence of inflammatory markers necessitates reimplantation within the peritoneum [6]. One-year survival rate of laparoscopic shunt diversion is poorer in infected pseudocysts (47%) as compared to non-infectious cases (100%) [6]. One-year-survival rate in shunts managed with distal shunt externalization and distal shunt externalization followed by peritoneal reimplantation is 82% and 90% respectively [6,14].

Case Highlights

In patients with VPS, shunt failure might be expected due to proximal malfunction, distal failure, catheter occlusion and infection. Accordingly, a high degree of suspicion for peritoneal abdominal pseudocyst is deemed necessary in those presenting with in those presenting with abdominal pain and abdominal swelling. Common causes of peritoneal CSF pseudocyst include infection, adhesions, previous abdominal surgery, foreign body reaction and immune mediated mechanism. Prompt confirmation of diagnosis with abdominal CT is required before moving forward with shunt explanation or revision. Treatment of infection is always required as subclinical infection can precipitate higher recurrence rates with associated increase in morbidity and mortality. Patients with VPS shunt should undergo regular follow up as shunt revision might be required as early as 5–10 years.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Consent taken.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, S.H.K & KM; Methodology, S.H.K & KM; Software, N.G.; Validation, N.A; Formal Analysis, N.A.; Investigation, S.H.K & VP.; Resources, N.A.; Data Curation, N.A.; Writing– Original Draft Preparation, S.H.K & KM.; Writing– Review & Editing, S.H.K.& KM.; Visualization, S.H.K.; Supervision, K.M..; Project Administration, K.M.

References

2. Erps A, Roth J, Constantini S, Lerner-Geva L, Grisaru-Soen G. Risk factors and epidemiology of pediatric ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection. Pediatr Int. 2018 Dec;60(12):1056–61.

3. Fatani GM, Bustangi NM, Kamal JS, Sabbagh AJ. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt-associated abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts and the role of laparoscopy and a proposed management algorithm in its treatment. A report of 2 cases. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2020 Aug;25(4):320–6.

4. Yim SB, Chung YG, Won YS. Delayed abdominal pseudocyst after ventriculoperitoneal shunt surgery: a case report. The Nerve. 2018 Oct 24;4(2):111–4.

5. Stone JJ, Walker CT, Jacobson M, Phillips V, Silberstein HJ. Revision rate of pediatric ventriculoperitoneal shunts after 15 years. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2013 Jan;11(1):15–9.

6. Whittemore BA, Braga BP, Price AV, De Oliveira Sillero R, Sklar FH, Megison SM, et al. Management of cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts in the laparoscopic age. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2023 Dec 15;33(3):256–67.

7. Mobley LW 3rd, Doran SE, Hellbusch LC. Abdominal pseudocyst: predisposing factors and treatment algorithm. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005 Mar-Apr;41(2):77–83.

8. Leung GK. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pseudocyst presented with inferior vena caval obstruction and hydronephrosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2010 Sep;26(9):1243–5.

9. Egelhoff J, Babcock DS, McLaurin R. Cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts: sonographic appearance and clinical management. Pediatr Neurosci. 1985-1986;12(2):80–6.

10. Erşahin Y, Mutluer S, Tekeli G. Abdominal cerebrospinal fluid pseudocysts. Childs Nerv Syst. 1996 Dec;12(12):755–8.

11. Yuh SJ, Vassilyadi M. Management of abdominal pseudocyst in shunt-dependent hydrocephalus. Surg Neurol Int. 2012;3:146.

12. Gaskill SJ, Marlin AE. Pseudocysts of the abdomen associated with ventriculoperitoneal shunts: a report of twelve cases and a review of the literature. Pediatr Neurosci. 1989;15(1):23-6; discussion 26–7.

13. Raghavendra BN, Epstein FJ, Subramanyam BR, Becker MH. Ultrasonographic evaluation of intraperitoneal CSF pseudocyst. Report of 3 cases. Childs Brain. 1981;8(1):39–43.

14. Erwood A, Rindler RS, Motiwala M, Ajmera S, Vaughn B, Klimo P, et al. Management of sterile abdominal pseudocysts related to ventriculoperitoneal shunts. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019 Oct 11;25(1):57–61.