Abstract

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women worldwide, with the highest mortality rates. While breast tumors can have heterogeneous biology, the mutational burden/genomic alterations, etc, are relatively less when compared to other malignancies like pancreatic cancer or glioblastomas, rendering breast tumors comparatively less aggressive. Despite this, adjuvant chemotherapy, which was devised as a means to reduce the risk of distant recurrence, has become the mainstay treatment choice for a majority of these patients, but is proving effective only for a subset. Therefore, efficient and effective treatment planning should involve strategies to de-escalate therapy regimens to balance the benefits and side effects of each therapy.

To circumvent the dilemma of relying solely on clinical parameters for chemotherapy treatment decisions, molecular profiling was introduced to look for signatures that better describe underlying tumor biology and act as an effective prognostic tool. This review discusses the advancements in prognostic tools for early breast cancer patients, giving a comprehensive overview of several commercially available prognostic tests. We also discuss CanAssist Breast®, a relatively newer entry into the field of prognostic tests and the only one that uses immunohistochemistry as a platform coupled with Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Abbreviations

AGO: Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynäkologische Onkologie (German Gynecological Oncology Group); AI: Artificial Intelligence; ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology; CAB: CanAssist Breast®; ER: Estrogen Receptor; ESMO: European Society for Medical Oncology; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor; HR: Hormone Receptor; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; NPI: Nottingham Prognostic Index; PR: Progesterone Receptor; SAARC: South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation; TNM: Tumor, Node, Metastasis

Introduction

Breast cancer accounts for the highest incidence and mortality rates among all cancer types in women worldwide [1]. The onset of widespread awareness and screening programs has significantly contributed to the early detection and management of breast cancer, possibly contributing to the increased incidence rates as well as the decreased mortality rates over the years [1,2]. Our understanding of the disease as a complex, heterogeneous neoplasm has also evolved through these years based on emergent molecular information made available through the advancement of science and technology. Currently, the most common and widely accepted classification of breast cancer stems from an immunohistochemical perspective based on the expression of the hormone receptors (HR)- estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR), and the human epidermal growth factor (HER2) [3]. According to this classification, the four main subtypes of breast cancer are HR+/HER2-, HR-/HER2-, HR+/HER2+, and HR-/HER2+, with approximately 70% of female breast cancer patients being diagnosed with the HR+/HER2- (hormone receptor-positive, HER2 negative) subtype of the disease [3,4]. These four subtypes are associated with distinct risk profiles and have different treatment strategies, considering other parameters, such as cancer stage and the patient's overall health status [5]. The patients diagnosed with HR+/HER2- breast cancer are treated using a multimodal approach that involves surgery, radiation, and adjuvant or neoadjuvant systemic therapies such as endocrine therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapies [6]. The treatment plans are usually devised after assessing critical clinicopathological parameters such as the TNM status, tumor grade, HR/HER2 expression status, age, and the expression of Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker. The TNM staging indicates the tumor size, lymph node involvement, and the distant metastasis status of the patient at the time of presentation [7]. The tumor grading determines the differentiation status of the tumor, where well-differentiated tumors have a better prognosis than poorly differentiated tumors [8]. Even after considering all these parameters for devising treatment plans for patients, they still face a high 50% risk of cancer recurrence in the first 5 years after treatment and even a persistent long-term recurrence risk beyond 10 years [6].

In the last couple of decades, several tests have been designed with the intent of molecular profiling tumors to provide biological information that can aid in understanding the nature of cancer and, therefore, guide the physician in designing treatment plans suited for each patient. In this review, we discuss the advancements in the field of breast cancer prognosis and the several prognostic tests that are commercially available, with a special emphasis on CanAssist Breast®, one of the newer entries in the market, developed for Indian patients.

Need for Breast Cancer Prognostication

At present, the high risk of distant recurrence, which can be fatal as against local recurrence, has significantly contributed to the prevalent use of chemotherapy regimens in treatment plans. Although the inclusion of adjuvant chemotherapy along with endocrine therapy has resulted in a substantial reduction in the risk of recurrence and death in patients with HR+/HER2- breast cancer [9], the extent of benefit from the chemotherapy varies within different subsets of patients with differing underlying risks of cancer recurrence which is poorly understood [10]. It is often observed that patients of the same age diagnosed with the same-stage disease can have differing outcomes, and the importance of biology before anatomy is realized.

For the majority of patients diagnosed with HR-positive breast cancer, adjuvant endocrine therapy is recommended irrespective of other factors like menopausal status, age, or HER2 status of the tumor. For patients diagnosed with node-positive disease, the recommended treatment regimen is adjuvant chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy [11].

Although adjuvant chemotherapy has played a significant role in the management of breast cancer, it is to be noted that the meta-analyses performed by the EBCTCG showed the reduction in risk of recurrence by adjuvant chemotherapy to be unaffected by factors such as age, nodal status, tumor diameter or grade, ER expression and that use of chemotherapy led to only a one-third decrease in the cancer mortality rate [9,12]. This suggests that adjuvant chemotherapy fails to impart its purported benefits for a significant subset of the patients. Moreover, the clinical benefits of chemotherapy often overshadow the multiple adverse effects associated with it, such as cardiac toxicity, secondary leukemia, cognitive function, and neurotoxicity, impacting the long-term quality of life of the patients [13]. This has led to an era of ‘de-escalation’ of treatment and opened up the need for better ‘prognostic’ tools that can assess individual patients’ risk of cancer recurrence based on a deeper biological understanding of the disease and thereby aid the process of optimal treatment planning, leading to de-escalation of adjuvant chemotherapy and its associated adversities [14,15].

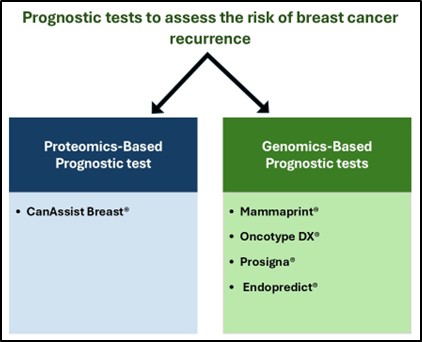

The currently available prognostic tools are designed to assess the molecular characteristics of tumors based on either their proteomic or genomic expression profiles. The following sections describe some commonly used prognostic tests for therapy guidance in early breast cancer patients (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.The figure depicts a schematic representation of some of the commonly used commercial prognostic tests to assess the risk of breast cancer recurrence.

|

Test name |

Innovator/Manufacturer |

Methodology (Genomics/Proteomics) |

No. of genes/proteins assessed |

Risk categories |

|

CanAssist Breast® |

OncoStem Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd, India |

Proteomics |

5 |

Risk score 0 - 15.5: Low risk |

|

Mammaprint® |

Agendia Inc., USA |

Genomics |

70 |

Index score 0.001 - 1.000: Low risk |

|

Oncotype DX® |

Genomic Health Inc., USA; Exact Sciences, USA |

Genomics |

21 |

Recurrence score <18: Low risk |

|

Prosigna® |

NanoString Technologies Inc., USA; Veracyte Inc, USA |

Genomics |

50 |

Continuous risk of recurrence score (ROR) from 0-100 is used to identify risk categories. Patients are classified as low, intermediate, or high risk based on ROR score ranges adjusted for different intrinsic subtypes and clinical parameters [16,48] |

|

EndoPredict® |

Myriad Genetics Inc., USA |

Genomics |

12 |

EP score <5 or EPclin score<3.3: Low risk |

CanAssist Breast®

Over the years, a few prognostic tests have entered the commercial market for molecular risk scores (Oncotype DX®, Mammaprint®, Prosigna®, Endopredict®, MammaTyper, Breast Cancer Index) [7,16]. However, it is to be noted that all of these prognostic tests are genomics-based and have been developed and validated in Western populations, therefore raising concerns regarding their application to Asian populations [17,18]. Studies have noted considerable differences between the incidence and biology of breast cancer in Asian women, with approximately 50% of the diagnoses being made under the age of 50 years and the detection of early and small breast tumors being negatively impacted due to the generally small-volume breasts and relatively dense parenchymal breast tissue in these women [19,20]. Recent research has also shown that the molecular landscape of Asian breast cancers varies from that of the Caucasian populations, with a significantly higher incidence of HER2+ disease [21,22]. These studies highlight the need for developing prognostic tests that account for the ethnic and molecular diversity of cancers and are validated in appropriately diverse patient cohorts.

CanAssist Breast® (CAB) (OncoStem Diagnostics Pvt. Ltd, India) is the first proteomics-based prognostic test developed on South Asian/Indian patients and validated in global studies. Although a majority of the widely used prognostic assays are based on gene expression profiling, it is to be noted that the transcriptional abundance of genes is not always correlated with the corresponding protein expression or its post-translational modifications. Immunohistochemical studies prove superior, allowing for protein expression analysis with subcellular precision. Considering these aspects, CAB was developed as a novel immunohistochemistry-based risk classifier of metastasis in early-stage ER+ breast cancer [23,24].

A 298-sample retrospective training set consisting of samples primarily from Indian patients was used to design the test, which calculates a CAB risk score using a machine-learning-based algorithm that combines the expression of five chosen biomarkers and the three clinicopathological parameters: tumor size, tumor grade, and node status. The biomarkers used in the test- CD44, ABCC4, ABCC11, N-cadherin, and pan-cadherin are selected from a larger pool of candidate biomarkers involved in the regulation of the critical hallmarks of cancer. These biomarkers were selected based on their role in tumor metastasis and are distinct from other proliferation and gene–expression–based prognostic signatures. The CAB algorithm integrates the information regarding the expression of the five biomarkers and the three clinicopathological parameters to determine a CAB risk score indicative of the probability of distant recurrence in 5 years. CAB was independently clinically validated in multiple studies in the US, Spain, Germany, Italy, Austria, and the Netherlands on ~ 4,000 patients [23-28].

The use of CAB has been steadily increasing over the past few years, and several studies have been conducted to further validate and cement its role as an effective prognostic tool for Indian breast cancer patients. The CAB stratification of patients as low-risk or high-risk was also statistically significant compared to Ki-67 and IHC4 score-based stratification systems. It was also found that the CAB test classified 17% of node-negative patients as high-risk, whereas 65% of node-positive patients were classified as low-risk. The similar rates of recurrence in CAB low-risk patients with node-negative and node-positive disease indicate that chemotherapy may not be beneficial for all node-positive patients, further highlighting the relevance of proteomic parameters detailing the biology underlying the disease over anatomy/clinicopathologic features in assessing the risk of recurrence [29].

Attempts are ongoing to validate the efficacy of CAB using different sample types and in various patient cohorts to broaden the scope of its application. A prerequisite for CAB testing is the availability of treatment-naïve samples since any form of therapy can alter the tumor biology and hence cannot be further used for appropriate risk assessment. Although CAB is typically performed on surgical specimens, core needle biopsies are the only treatment-naïve samples available in certain situations. Therefore, CAB has been validated for its efficacy in such samples by comparing it with surgical specimens, which shows excellent concordance, further alluding to the feasibility of core needle biopsy samples as acceptable for CAB testing [30]. The CAB test has also been validated for its high throughput potential by testing tissue microarrays on an automated platform, adding to its repertoire of applications [31].

CAB has also been validated to show high concordance with the widely used prognostic test Oncotype DX® [25]. Another study comparing the risk stratification by CAB and two other prognostic tests, PREDICT and Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI), observed high concordance between the tests in the low-risk categories. However, the high-risk category showed discordant results. CAB segregates a significant subset of high-risk patients in both PREDICT and NPI sets as low-risk, thereby preventing over-treatment [26]. Further studies to assess the prognostication efficiency of CAB include the retrospective validation study of the test on a multi-country European cohort of 864 patients from Spain, Italy, Austria, and Germany, which showed robust results suggesting the applicability of the test independent of ethnic differences [27]. A recent study in a Dutch sub-cohort of the completed prospective randomized TEAM trial showed that the prognostic relevance of the test remains valid even 10 years post-diagnosis and, therefore, remains highly relevant in its potential to guide treatment plans for patients [28]. So far, CAB has been prescribed for ~7,500 HR+/HER2- patients, and the growing test numbers indicate an increase in clinicians' confidence in the test for guiding personalized treatment plans [32]. The validation in Asian cohorts and the relatively affordable nature of the test compared to its Western counterparts have led to CAB being recommended by consensus guidelines for managing early breast cancer in India, SAARC, and other Asian low and middle-income countries [33].

Mammaprint®

The very first gene expression-based assay to determine breast cancer prognosis was the 70-gene classifier or Mammaprint® (Agendia Inc., USA) [16]. In a landmark study, DNA microarray analysis was performed on primary breast tumors of 117 young patients, and the data were used to develop a gene expression signature strongly predictive of “poor prognosis,” which indicated a short interval to distant metastases [34]. Subsequent studies showed that the components of the 70-gene signature form highly interconnected networks, with their expression levels being regulated by key tumorigenesis-related genes, and their biological functions reflect the six hallmarks of cancer as defined by Hanahan and Weinberg [35]. Towards the end of 2002, the group published another study showing the validation of the prognostic test in a group of 295 patients by predicting distant metastases within five years after treatment, further asserting the usefulness of the test in predicting the disease outcome and its superior standing compared to the standard systems based on clinical and histologic criteria prevalent at the time [36]. The independent large-scale retrospective study by the TRANSBIG Consortium on 302 node-negative patients further confirmed the prognostic value of the 70-gene signature in stratifying patients as low- or high-risk and the possibility of the test being utilized as a predictive tool in guiding treatment plans [37,38]. This emboldened the design and execution of the large-scale prospective clinical trial MINDACT, conducted on 6,693 women diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer. The study further strengthened the claim that a significant subset of these patients, although presented as clinically high-risk, fall within the low-genomic risk category and, therefore, can forego chemotherapy with similar outcomes [17,38,39]. Introduced in 2002, Mammaprint® remains one of the most widely used prognostic breast cancer tests, recommended by NCCN, ASCO, St.Gallen, ESMO, and AGO treatment guidelines [7].

Oncotype DX®

In yet another landmark study, a 21-gene RT-PCR assay was developed based on three independent clinical studies, making Oncotype DX® (Genomic Health Inc., USA; Exact Sciences, USA) the second gene expression-based prognostic test to enter the market for breast cancer [16,40]. The group selected 250 candidate genes from published literature and genomic databases to assess their expression profile in a group of 447 patients from three different clinical studies (hence a heterogeneous population) and to further correlate the expression status of these genes to recurrence status. The results from the study were employed to design a recurrence-score algorithm based on the expression of 21 genes, of which 5 were reference genes used for normalization, and 16 were cancer-related genes that included ER and HER2-associated genes, as well as genes involved in proliferation and invasion. The newly defined 21-gene signature and the recurrence-score algorithm were validated for their ability to quantify the likelihood of distant recurrence in patients enrolled in the large multicenter NSABP trial B-14 (tamoxifen-treated patients with node-negative, estrogen-receptor–positive breast cancer) [40].

The revised recurrence scoring system (scale of 0-100) by Oncotype DX® places patients with a risk score of below 11, 11-25, and above 25 as low risk, intermediate risk, and high risk of recurrence, respectively. Endocrine therapy is recommended for patients in the low-risk category. In contrast, high-risk patients are recommended chemoendocrine therapy, leaving patients with intermediate-risk scores without a definitive treatment plan that can be advisable based on the test. The large-scale prospective study TAILORx was designed to address this knowledge gap. Among the 9,719 eligible patients enrolled in the study (HR+/HER2-, axillary node-negative breast cancer) with follow-up information available, 6,711 (69%) were determined to have an intermediate risk score and were randomly assigned to either the endocrine or chemoendocrine treatment group. The findings from the study revealed that chemoendocrine therapy had similar benefits as endocrine therapy alone for patients with an intermediate risk of recurrence, further highlighting the minimal advantage offered by chemotherapy to a significant group of patients [41,42]. In light of these findings, as well as several other studies that yielded similar results showcasing the prognostic and predictive potential of Oncotype DX® in assessing recurrence risk and guiding treatment plans, it is now widely included in NCCN, ASCO, ESMO, and similar other treatment guidelines [7,16].

Prosigna®

The ER expression status of breast cancer plays a significant role in determining the prognosis of the patient. However, gene expression microarray studies have revealed that even within ER+ and ER- groups, there are subsets (intrinsic subtypes) with distinct molecular features, which led to an alternate system of breast cancer molecular subtyping consisting of the groups luminal A, luminal B, HER2-enriched, basal-like, and normal-like [43,44].

The Prosigna® (NanoString Technologies Inc., USA, ; Veracyte Inc, USA) test was developed with the intent to improve the landscape of breast cancer prognosis and prediction of chemotherapy benefit by creating a model based on the intrinsic subtypes, leading to the establishment of a 50-gene subtype predictor, which was evaluated and found efficient for prognosis in 761 patients with no systemic therapy and also for prediction of complete pathologic response to chemotherapy in a group of 133 patients [43]. In a comparison study performed using information available from the ATAC trial involving postmenopausal patients with hormone receptor-positive primary breast cancer from the tamoxifen- or anastrozole-alone groups, Prosigna® provided more prognostic information than Oncotype DX® with a better stratification of the intermediate and high-risk groups [45], and is also currently recommended by NCCN, ASCO, and other similar treatment guidelines [7].

Endopredict®

Endopredict® (Myriad Genetics Inc., USA) was another molecular prognostic test developed to predict the risk of distant recurrence in patients with ER+ and HER2- patients treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy alone. The risk score indicated by the test (EP) can be combined with the clinical parameters of nodal status and tumor size to arrive at an improved risk score EPclin that provides additional prognostic information. Both EP and EPclin scores were validated independently in patients from two Austrian randomized phase III trials - ABCSG-6 (n = 378) and ABCSG-8 (n = 1,324) and are recommended in major treatment guidelines [46].

Conclusions

Over the last couple of decades, our understanding of breast cancer biology has advanced to the point of better appreciating the heterogeneous nature of the disease crafted by diverse molecular landscapes across different patient groups. This diversity in tumor biology is now understood to be a significant factor driving response to different therapy regimens and, therefore, implicates the usage of prognostic tools that go beyond current methods of understanding the tumor biology from clinical characteristics to a deeper molecular level. The scope of molecular-level understanding of the disease should also be broadened to account for signatures unique to different ethnic groups, which would further warrant the validation of available tests on patients of diverse ethnicities. While the most commonly used prognostic tests are currently intended for use in HR+/HER2- breast cancer patients, their significant role in clinical therapy guidance highlights that usage of such tests for other breast cancer subtypes will take us even closer to the goal of personalized treatment for all breast cancer patients.

Limitations

This review focuses on some of the most commonly used tests in the market for breast cancer prognosis, with validation data available in the public domain, and has not included discussion on tests that are less commonly used or not extensively validated.

References

2. Bray F, McCarron P, Parkin DM. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(6):229-39.

3. Orrantia-Borunda E, Anchondo-Nuñez P, Acuña-Aguilar LE, Gómez-Valles FO, Ramírez-Valdespino CA. Subtypes of Breast Cancer. In: Mayrovitz HN, editor. Breast Cancer [Internet]. Brisbane (AU): Exon Publications; 2022.

4. National Cancer Institute. Female breast cancer subtypes - Cancer Stat Facts [Internet]. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast-subtypes.html

5. Cao LQ, Sun H, Xie Y, Patel H, Bo L, Lin H, et al. Therapeutic evolution in HR+/HER2- breast cancer: from targeted therapy to endocrine therapy. Front Pharmacol. 2024 Jan 24;15:1340764.

6. Huppert LA, Gumusay O, Idossa D, Rugo HS. Systemic therapy for hormone receptor-positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-negative early stage and metastatic breast cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023 Sep-Oct;73(5):480-515.

7. Fasching PA, Kreipe H, Del Mastro L, Ciruelos E, Freyer G, Korfel A, et al. Identification of Patients with Early HR+ HER2- Breast Cancer at High Risk of Recurrence. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2024 Feb 8;84(2):164-84.

8. Cuyún Carter G, Mohanty M, Stenger K, Morato Guimaraes C, Singuru S, Basa P, et al. Prognostic Factors in Hormone Receptor-Positive/Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Negative (HR+/HER2-) Advanced Breast Cancer: A Systematic Literature Review. Cancer Manag Res. 2021 Aug 20;13:6537-6566.

9. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG); Peto R, Davies C, Godwin J, Gray R, Pan HC, Clarke M, et al. Comparisons between different polychemotherapy regimens for early breast cancer: meta-analyses of long-term outcome among 100,000 women in 123 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012 Feb 4;379(9814):432-44.

10. Lopez-Tarruella S, Echavarria I, Jerez Y, Herrero B, Gamez S, Martin M. How we treat HR-positive, HER2-negative early breast cancer. Future Oncol. 2022 Mar;18(8):1003-22.

11. Gradishar WJ, Moran MS, Abraham J, Abramson V, Aft R, Agnese D, et al. Breast Cancer, Version 3.2024, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024 Jul;22(5):331-57.

12. Anampa J, Makower D, Sparano JA. Progress in adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: an overview. BMC Med. 2015 Aug 17;13:195.

13. Azim HA Jr, de Azambuja E, Colozza M, Bines J, Piccart MJ. Long-term toxic effects of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2011 Sep;22(9):1939-47.

14. Curigliano G, Burstein HJ, Winer EP, Gnant M, Dubsky P, Loibl S, et al. De-escalating and escalating treatments for early-stage breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Expert Consensus Conference on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2017. Ann Oncol. 2017 Aug 1;28(8):1700-12.

15. Burstein HJ, Curigliano G, Thürlimann B, Weber WP, Poortmans P, Regan MM, et al. Panelists of the St Gallen Consensus Conference. Customizing local and systemic therapies for women with early breast cancer: the St. Gallen International Consensus Guidelines for treatment of early breast cancer 2021. Ann Oncol. 2021 Oct;32(10):1216-35.

16. Sinn P, Aulmann S, Wirtz R, Schott S, Marmé F, Varga Z, et al. Multigene Assays for Classification, Prognosis, and Prediction in Breast Cancer: a Critical Review on the Background and Clinical Utility. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2013 Sep;73(9):932-40.

17. Cardoso F, van't Veer LJ, Bogaerts J, Slaets L, Viale G, Delaloge S, et al. MINDACT Investigators. 70-Gene Signature as an Aid to Treatment Decisions in Early-Stage Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016 Aug 25;375(8):717-29.

18. Albain KS, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Faghih A, Hayes DF, Geyer CE, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and Clinical Outcomes in Hormone Receptor-Positive, HER2-Negative, Node-Negative Breast Cancer in the Randomized TAILORx Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021 Apr 6;113(4):390-9.

19. Bhoo-Pathy N, Yip CH, Hartman M, Uiterwaal CS, Devi BC, Peeters PH, et al. Breast cancer research in Asia: adopt or adapt Western knowledge? Eur J Cancer. 2013 Feb;49(3):703-9.

20. Yu AYL, Thomas SM, DiLalla GD, Greenup RA, Hwang ES, Hyslop T, et al. Disease characteristics and mortality among Asian women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2022 Mar 1;128(5):1024-37.

21. Telli ML, Chang ET, Kurian AW, Keegan TH, McClure LA, Lichtensztajn D, et al. Asian ethnicity and breast cancer subtypes: a study from the California Cancer Registry. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Jun;127(2):471-8.

22. Pan JW, Zabidi MMA, Ng PS, Meng MY, Hasan SN, Sandey B, et al. The molecular landscape of Asian breast cancers reveals clinically relevant population-specific differences. Nat Commun. 2020 Dec 22;11(1):6433.

23. Ramkumar C, Buturovic L, Malpani S, Kumar Attuluri A, Basavaraj C, Prakash C, et al. Development of a Novel Proteomic Risk-Classifier for Prognostication of Patients With Early-Stage Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Biomark Insights. 2018 Jul 30;13:1177271918789100.

24. Attuluri AK, Serkad CPV, Gunda A, Ramkumar C, Basavaraj C, Buturovic L, et al. Analytical validation of CanAssist-Breast: an immunohistochemistry based prognostic test for hormone receptor positive breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2019 Mar 20;19(1):249.

25. Sengupta AK, Gunda A, Malpani S, Serkad CPV, Basavaraj C, Bapat A, et al. Comparison of breast cancer prognostic tests CanAssist Breast and Oncotype DX. Cancer Med. 2020 Nov;9(21):7810-8.

26. Gunda A, Eshwaraiah MS, Gangappa K, Kaur T, Bakre MM. A comparative analysis of recurrence risk predictions in ER+/HER2- early breast cancer using NHS Nottingham Prognostic Index, PREDICT, and CanAssist Breast. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022 Nov;196(2):299-310.

27. Gunda A, Basavaraj C, Serkad V CP, Adinarayan M, Kolli R, Siraganahalli Eshwaraiah M, et al. A retrospective validation of CanAssist Breast in European early-stage breast cancer patient cohort. Breast. 2022 Jun;63:1-8.

28. Zhang X, Gunda A, Kranenbarg EM, Liefers GJ, Savitha BA, Shrivastava P, et al. Ten-year distant-recurrence risk prediction in breast cancer by CanAssist Breast (CAB) in Dutch sub-cohort of the randomized TEAM trial. Breast Cancer Res. 2023 Apr 14;25(1):40.

29. Bakre MM, Ramkumar C, Attuluri AK, Basavaraj C, Prakash C, Buturovic L, et al. Clinical validation of an immunohistochemistry-based CanAssist-Breast test for distant recurrence prediction in hormone receptor-positive breast cancer patients. Cancer Med. 2019 Apr;8(4):1755-64.

30. Savitha BA, Shrivastava P, Bhagat R, Krishnamoorthy N, Shivashimpi DK, Bakre MM. Comparison of Risk Stratification by CanAssist Breast Test Performed on Core Needle Biopsies Versus Surgical Specimens in Hormone Receptor-Positive, Her2-Negative Early Breast Cancer. Cureus. 2024 Sep 23;16(9):e70054.

31. Serkad CPV, Attuluri AK, Basavaraj C, Adinarayan M, Krishnamoorthy N, Ananthamurthy SB, et al. Validation of CanAssist Breast immunohistochemistry biomarkers on an automated platform and its applicability in tissue microarray. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021 Oct 15;14(10):1013-21.

32. Maniar V, Rajappa S, Bakre M, Savitha BA. Real-world data on prognostication of early-stage breast cancer patients using CanAssist Breast- first immunohistochemistry based prognostic test developed and validated on Asians. ESMO Congress: 2024; Barcelona [cited 2025 Mar 5]. Available from: https://oncostem.com/assets/files/ESMO%20Europe%202024%20final%20poster-%2009_09_24.pdf

33. Parikh P, Babu G, Singh R, Krishna V, Bhatt A, Bansal I, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of HR-positive HER2/neu negative early breast cancer in India, SAARC region and other LMIC by DELPHI survey method. BMC Cancer. 2023 Jul 31;23(1):714.

34. van 't Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002 Jan 31;415(6871):530-6.

35. Tian S, Roepman P, Van't Veer LJ, Bernards R, de Snoo F, Glas AM. Biological functions of the genes in the mammaprint breast cancer profile reflect the hallmarks of cancer. Biomark Insights. 2010 Nov 28;5:129-38.

36. van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van't Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, Voskuil DW, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002 Dec 19;347(25):1999-2009.

37. Cardoso F, Van't Veer L, Rutgers E, Loi S, Mook S, Piccart-Gebhart MJ. Clinical application of the 70-gene profile: the MINDACT trial. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 10;26(5):729-35.

38. Buyse M, Loi S, van't Veer L, Viale G, Delorenzi M, Glas AM, et al. Validation and clinical utility of a 70-gene prognostic signature for women with node-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Sep 6;98(17):1183-92.

39. Cardoso F, Piccart-Gebhart M, Van't Veer L, Rutgers E; TRANSBIG Consortium. The MINDACT trial: the first prospective clinical validation of a genomic tool. Mol Oncol. 2007 Dec;1(3):246-51.

40. Paik S, Shak S, Tang G, Kim C, Baker J, Cronin M, et al. A multigene assay to predict recurrence of tamoxifen-treated, node-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 30;351(27):2817-26.

41. Sparano JA, Paik S. Development of the 21-gene assay and its application in clinical practice and clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Feb 10;26(5):721-8.

42. Sparano JA, Gray RJ, Makower DF, Pritchard KI, Albain KS, Hayes DF, et al. Adjuvant Chemotherapy Guided by a 21-Gene Expression Assay in Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 12;379(2):111-21.

43. Parker JS, Mullins M, Cheang MC, Leung S, Voduc D, Vickery T, et al. Supervised risk predictor of breast cancer based on intrinsic subtypes. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 10;27(8):1160-7.

44. Yersal O, Barutca S. Biological subtypes of breast cancer: Prognostic and therapeutic implications. World J Clin Oncol. 2014 Aug 10;5(3):412-24.

45. Dowsett M, Sestak I, Lopez-Knowles E, Sidhu K, Dunbier AK, Cowens JW, et al. Comparison of PAM50 risk of recurrence score with oncotype DX and IHC4 for predicting risk of distant recurrence after endocrine therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Aug 1;31(22):2783-90.

46. Filipits M, Rudas M, Jakesz R, Dubsky P, Fitzal F, Singer CF, et al. EP Investigators. A new molecular predictor of distant recurrence in ER-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer adds independent information to conventional clinical risk factors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011 Sep 15;17(18):6012-20.

47. Soliman H, Shah V, Srkalovic G, Mahtani R, Levine E, Mavromatis B, et al. MammaPrint guides treatment decisions in breast Cancer: results of the IMPACt trial. BMC Cancer. 2020 Jan 31;20(1):81.

48. Prosigna Breast Cancer Prognostic Gene Signature Assay [Internet]. Available from: https://www.prosigna.com/patients/

49. Dubsky P, Brase JC, Jakesz R, Rudas M, Singer CF, Greil R, e al. Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group (ABCSG). The EndoPredict score provides prognostic information on late distant metastases in ER+/HER2- breast cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2013 Dec 10;109(12):2959-64.