Abstract

Background: Neurodegenerative diseases, such as the Alzheimer and the Parkinson's, currently lack effective pharmacotherapies. They are posing a significant global health threat, and it is urgent to discover and develop effective pharmacotherapies for patients. However, due to pathogenic mechanisms are poorly understood, the interventional drug clinical trials for neurodegenerative diseases have high failure rates.

Methods: This study explored a new approach for discovering pharmacotherapies for neurodegenerative diseases—repurposing those anti-cancer agents which could potentially treat neurodegenerative diseases. The core implication is that existing anti-cancer drugs, which have already undergone extensive safety and efficacy testing, could be repurposed, potentially accelerating the drug development pipeline for neurodegenerative diseases. By leveraging the hypothesized inverse correlation between cancer and Alzheimer's, and applying a rigorous computational systems biology approach (specifically, the link prediction on a heterogeneous bipartite drug-disease network), the study has unveiled promising anti-cancer drug-neurodegenerative disease potential therapeutic association drug-disease pairs. Eight distinct link prediction algorithms were rigorously tested on the heterogenous bipartite drug-disease therapeutic linkage network. Predictors’ performance was assessed using a leave-one-out cross-validation strategy, analyzing the mean and standard deviation of rank scores.

Results: The Rooted PageRank predictor emerged as the most effective algorithm during benchmarking and was subsequently chosen for predicting novel drug-disease therapeutic association linkages. The identification of specific drug-disease pairs, such as Oblimersen sodium for Alzheimer's disease, validated by existing literature, provides concrete starting points for further preclinical and clinical investigations.

Conclusions: This innovative computational approach not only broadens the scope of potential therapeutic molecules for neurodegenerative diseases, pinpointing anti-cancer drugs as potential therapeutic candidates, but also validates the utility of systems biology and network medicine in identifying novel drug-disease therapeutic relationships, ultimately providing concrete starting points for further preclinical and clinical investigations for neurodegenerative disease pharmacotherapies, and offering hope for new treatments for millions affected by neurodegenerative disorders.

Introduction

The neurodegenerative disorders result from loss of the structure and functions of neurons, causing brain dysfunctions and cognitive problems, e.g., the loss of memory, and incapability of linguistic ability. Such cognitive problems are threatening patients’ daily life and may lead to death. The neurodegenerative diseases have multiple subtypes, including but not limited to, the Alzheimer’s disease, the Parkinson’s diseases, the Huntington’s disease, the Batten disease, and the Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amongst, the Alzheimer’s disease and the Parkinson’s disease are the most typical ones and the most commonly seen and heard syndromes. In fact, the Alzheimer’s disease is the most common neurodegenerative disorder and the Parkinson’s disease is the second one [1,2].

Thanks to the long-term efforts of scientists, factors contributing to neurodegenerative diseases have been partially found. For example, the relevant genetic mutations and epigenetic effects were identified [3,4]; the aggregation of misfolded proteins, such as the tau protein and beta amyloid, were detected in neurodegenerative animal models [5,6]; the mitochondrial dysfunctions and the programmed cell death were also shown to associate with the neurodegenerative diseases [7,8].

Specifically, for Alzheimer’s disease, a number of hypotheses have been postulated to explain the genetic causes of it. The two of the most representative ones are amyloid hypothesis and tau hypothesis. The amyloid hypothesis suggests that the deposition of the extracellular beta amyloid causes Alzheimer’s disease [9], and the tau hypothesis claims the abnormalities of tau protein cause the disease [10]. These hypotheses have guided pharmaceuticals to invest great amounts of resources and efforts into developing therapies for treating the disease. For example, Eli Lilly developed a monoclonal antibody Solanezumab based on the beta amyloid hypothesis and methylthioninium chloride was developed for inhibiting the tau protein aggregation [11–13]. Nevertheless, none of them is able to completely cure Alzheimer’s disease. Solanezumab does not work on the patients who are already suffering the disease while the methylthioninium chloride failed in clinical trial phase III [14]. Another clinical trial of Verubecestat, an inhibitor of the upstream proteins of the beta amyloid, was also stopped in early 2017. So did the Aducanumab in 2019 [15,16].

Above disappointing facts urge researchers to find new ways for drug discovery of Alzheimer’s disease as well as other types of neurodegenerative diseases. Drug repositioning could be a favorable strategy for this purpose [11–14]. Repositioning discovers new therapeutic indications of existed drugs or chemical compounds, which saves great amount of resources and efforts than developing a novel drug from the very beginning [17,18]. There are succeeded drug repositioning cases [19,20]. Besides the famous story of Pfizer’s Viagra, two other examples are Requip and Colesevelam. Requip and Colesevelam are originally anti-Parkinsonion agent and hyperlipidemia therapy and then repositioned for restless leg syndrome and type 2 diabetes, respectively.

Combining drug repositioning methods with the interesting evidences suggesting the inverse correlation between cancers and neurodegenerative diseases [21,22], researchers tried to reposition the existed anti-cancer drugs for neurodegenerative diseases, e.g., Carmustine [19], copper (II) chelating molecules [20], Tamibarotene [17], etc [18]. While relatively simpler than ab initio drug discovery, such in vitro and in vivo experiments are still laborious, time-consuming as well as with risks of failure. Therefore, before initiating wetlab experiments, it is necessary and of vital importance to select the high potential drug candidates from the compound pool. To this end, in silico systems biology approaches help via enabling large scale data analysis and computational predictive analysis.

In this work, in order to predict anti-cancer drug that has potential to work for neurodegenerative diseases, relevant drug and disease data were collected and similarity analyses were carried out for drug pairs and disease pairs. After data integration, a heterogeneous bipartite drug-disease network was constructed, and then Leave-One-Out and rank score were used to evaluate the predictive performance of different link predictors. On selecting the one with best predictive performance, i.e., the Rooted PageRank predictor, it was used to predict the anti-cancer drugs that could possibly be used to treat neurodegenerative diseases via network analyses.

Materials and Methods

Data

Multiple databases were queried for collection of the data of neurodegenerative diseases, including KEGG [23], DisGeNet [24], the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database [25], and the Neurodegenerative Disease Variation Database [26]. While the number of neurodegenerative diseases with sufficient phenotypic data available was limited. For example, 81 kinds of neurodegenerative diseases were found in KEGG, while many are not well-studied ones and parts of them are found to be rare diseases such as Lewy body dementia and Refsum disease. The drug data were collected from KEGG [23], DrugBank [27], Drugs@FDA, ChEMBL [28], and Pubchem database [29]. Two classes of drug data were collected for this study. One was the U.S. FDA-approved drugs for treating different sorts of neurodegenerative diseases, such as the Donepezil hydrochloride and Galantamine hydrobromide. These drugs were approved for treating the Alzheimer’s disease, while none of them can completely cure the Alzheimer’s disease.

For the purpose of similarity analysis and network construction, data screening was conducted. Neurodegenerative diseases lacking phenotypic data and those not associated with U.S. FDA-approved drugs were excluded from further data processing. Finally, we narrowed down the number of neurodegenerative diseases to be studied to 32 types, and we had 33 pairs of such drug-disease therapeutic relations including 29 drugs and 6 types of neurodegenerative diseases. The other class of drug data that required for this study was the anti-cancer drugs, which is also termed Antineoplastic agents under the category World Health Organization-defined Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical Classification (ATC) system. With the code “L01”, the anti-cancer drugs were located in ATC system. The query of ATC code “L01” against PubChem returned 1,301 hits of antineoplastic compounds, and 382 annotated with the term “Pharmacology action” were downloaded for further processing. Removal of invalid and structurally redundant drug data gave 171 anti-cancer drugs to our valid dataset of anti-cancer drugs.

Similarity analysis gives highly similar node pair a linkage in the network and hence making the network topological information richer and the better basis for hidden link detections through link predictors. To this end, the pair-wise structure comparison of total 201 drugs (30 U.S. FDA-approved drugs treating neurodegenerative disease and 171 anti-cancer drugs) was carried out using in house scripts and ChemmineR tool [30]. Molecular descriptor of atompair and fringerprint were applied to vectorize the chemical structure of drugs and the Tanimoto Similarity Coefficient [31] was used to measure the structure similarity between a pair of drugs. And for the 32 kinds of neurodegenerative diseases whose phenotypic/symptom data were available, using in house script and dSimer [32], the phenotypic similarity score of disease pairs was represented and measured by cosine similarity coefficient. Similar to Tanimoto Similarity Coefficient, the higher value of cosine similarity coefficient (from 0 to1) indicates a stronger similarity. Upon aforementioned similarity analysis for both drug pairs and disease pairs, two matrices of similarity score were combined with the bipartite approved drug-disease association data so as to further generate a large adjacency matrix of a heterogeneous bipartite graph for the purpose of link prediction.

Link predictors

Link prediction methods predict if hidden links or unobservable edges exist in network. A simple definition could be like: given a graph G = (V, E), where V is the set of nodes and E is the set of the edges in the graph G. If the set U denotes all the possible edges of G, the link prediction problem is to detect and rank the likelihood of edges from the set U – E. Note that in order to test the predictive performance of link predictors, E can be divided in to training set ET and probing/validation set EP. Therefore, ET∪EP = E and EP ∩ ET = Φ. In this study, the drug repositioning problem can be formulated to the link prediction problem. i.e., in drug-disease network, the likelihood of a link between an anti-cancer drug node and a neurodegenerative disease node can be predicted. If there exists such a link, we consider therapeutic effect may exist between the connected anti-cancer drugs and the neurodegenerative diseases. We chose network link prediction methods for computational drug repositioning purpose because of its advantages of being able to directly apply to network models and its low requirements on computation costs, compared with other indirectly link prediction methods, for example, the machine learning approaches which require higher computation costs. What is more, machine learning methods also have higher and more complicated requirements for generating and preparing the datasets, such as the feature datasets of different neurodegenerative diseases.

In this work, 8 types of link predictors were chosen. They are the Jaccard Similarity Coefficient [33], the Resource Allocation Index [34], the Degree Product Index [35,36], Katz Index [37], SimRank Predictor [38], Rooted PageRank Predictor [39], Graph Distance Predictor [40] and the Random predictor. All link predictors predict links using the topological structures of networks. Amongst, predictor of Jaccard Similarity Coefficient, Resource Allocation Index and Degree Product Index are the class of common neighbors-based link predictors, and their predictions rely on local topological similarities. The theoretical basis of the common neighbors index lies in the neighborhood similarity between two different nodes. Basically, it is considered that two nodes are likely to have a link to each other if they share greater number of common neighbor nodes. The greater the number of the common neighbors is, the more likely that two nodes have link between them. The Katz Index and Graph Distance Predictor can be classified into path-based link predictor. These two predictors count longer edges or paths for network link predictions. Rooted PageRank Predictor and SimRank Predictor are eigenvector-based link predictors while the Random Predictor predicts links in random way, and it served as a control reference. Features of aforementioned predictors were summarized in Table 1.

|

Predictor |

Description |

|

Jaccard Similarity Coefficient |

A classic type of common neighbors-based link predictors and has been widely applied in link prediction studies of multi-disciplines. The value ranges from 0 to 1 and depends on the ratio of the number of two nodes’ shared common neighbors (intersection of neighbor nodes) to the number of sum (union of neighbor nodes) of two nodes’ neighbor nodes [31,33,41]. |

|

Resource Allocation Index |

A modified type of common neighbors-based link predictors, it is defined as the reciprocal of the commonly shared neighbor nodes of a pair of nodes [34]. |

|

Degree Product Index |

The degree product index is the outcome of the multiplication of two nodes’ number of neighbor nodes. It is based on the hypothesis of preferential attachment model that, nodes with larger nodal degree numbers tend to form new links so as to accumulate higher degree number according to the power-law distribution [35,36]. |

|

Katz index |

Katz index is a type of path-based link predictors, and it considers all the possible path and distance from one node to another [37]. Katz index is considered a kind of extended common neighbors-based predictor. Unlike the common neighbors-based predictors, which only consider the node of 1-step away as neighbor, nodes of multiple steps away from the seed nodes are also considered as neighbors in link prediction. Katz index therefore partially overcomes the limitation of common neighbors-based predictors that they fail to analyze two nodes without (1-step) common neighbors. While Katz index’s consideration of all the possible paths and connection patterns in the networks makes the computational requirements become high. |

|

Graph Distance Predictor |

Graph distance predictor is also a kind of path-based link predictors. It measures a pair of nodes’ path-length and weights of path [40]. |

|

Rooted PageRank Predictor |

Rooted PageRank method works via an intuitive mechanism based on hierarchical relations of network [39]. For all nodes in a network, Rooted PageRank algorithm considers each single node of the network as the root node and then scores and ranks all other nodes against the root node according to specific hierarchical function. After all iterations are done, the top-ranked node pairs could be considered the potential links. The Rooted PageRank is in fact a kind of modification form or extension of the original PageRank algorithm [42]. |

|

SimRank Predictor |

SimRank uses the network topological structure to detect similarity [43]. It supposes that two objects are similar if they have similarity topological structures or referred by similar objects. SimRank goes through all the node pairs of the network and hence is usually computation-intensive. |

|

Random Predictor |

The Random predictor predicts links in random way, and it served as a control reference to other predictors’ outcomes. |

Metric and link prediction

In order to evaluate the predictive performances of different predictors, the Leave-One-Out strategy [44], combined with rank score was selected to be the metric. The combination of Leave-One-Out strategy with “Mean value ± Standard Deviation” of the rank score worked via the following way. For each round, one of the known drug-disease edge was removed from the drug-disease network. And then link predictor was applied to the network, and the score (or likelihood) of all the unobserved edges including the removed one at the beginning was computed and subsequently ranked from higher to lower score order. Locate the ranked position of the deleted edge which serves as a positive reference for predictors’ performance evaluation. If the known and deleted edge had high score and ranked at the top of the predicted drug-disease edge score list, the applied predictor could be considered an effective one. Else, the predictor was not. The number of ranked position of the deleted edge divided by the total number of edge predicted is the value of rank score. It could be easily figured out that the value of rank score ranges from 0 to 1, and simply the smaller value the rank score is, the better the predictor’s performance is. Repeat above actions until all the known drug-disease edges have been deleted for once. Suppose there are totally N of such edges. And then calculate the “Mean value ± Standard Deviation” of these N rank scores of each predictor. In such ways, the performances of different link predictors could be benchmarked quantitatively. Similarly, smaller values of “Mean value ± Standard Deviation” indicate the better and more stable performance of a predictor.

Upon identification of the best link predictor through benchmarking, the best one—the Rooted PageRank predictor, was applied to the full network dataset so as to predict potential link between anti-cancer drug and neurodegenerative disease. Similarly, the predicted anti-cancer drug-neurodegenerative disease association edges were ranked according to the scores returned by algorithm. And then top-ranked predictive drug-disease pairs were considered the potential anti-cancer drugs that have effect on neurodegenerative disease. Literature databases were subsequently searched in order to find support for our prediction.

Results

Heterogeneous bipartite drug-disease network

Through data screening, neurodegenerative diseases without phenotypic data and disease that do not have U.S. FDA-approved drugs were removed. As a result, 32 types of neurodegenerative diseases and 33 pairs of such drug-disease therapeutic relations including 29 drugs and 6 types of neurodegenerative diseases were retained for further analyses. The diseases included were the Alzheimer’s disease, Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, Huntington’s disease, Parkinsonian disorder/syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, and Postherpetic neuralgia (Supplementary Table S1). These data indicate the existence of multiple “me-too” drugs for only small number of specific neurodegenerative diseases and a large number of neurodegenerative diseases lack pharmacotherapies yet.

The disease-disease phenotypic similarity was analyzed, as described in the method section. Table 2 listed the top-ranked 8 most similar neurodegenerative disease pairs. Amongst, the Parkinson’s disease and Parkinsonian disorder had the highest score of cosine similarity coefficient (about 0.92) in terms of phenotypic similarity. Generally, most of the disease pair-wise cosine similarity coefficients were low (around 0.1), indicating that most of these diseases did not share lots of similar or common phenotypes/symptoms. Several cases of low similarity disease pairs were also found. Such as the disease pair of Cockayne Syndrome and the Parkinsonian Disorders (whose similarity coefficient was zero) and the disease pair of Lewy Body Disease and Canavan Disease (whose similarity coefficient was lower than 0.02). For molecular structure similarity of drug pairs, the Tanimoto Similarity Coefficient was used to measure the similarity, while most of the coefficient values were low. Specifically, it was expected that high similarity between approved drugs treating neurodegenerative diseases and anti-cancer drug could be found, as it is more likely for such anti-cancer drugs to be associated to neurodegenerative disease nodes in the network link predictions.

|

ID |

Disease A |

Disease B |

Cosine Similarity Coefficient |

|

1 |

Parkinson’s Disease |

Parkinsonian Disorders |

0.92 |

|

2 |

Spinocerebellar Degenerations |

Cerebellar Ataxia |

0.88 |

|

3 |

Huntington Disease |

Neuroacanthocytosis |

0.86 |

|

4 |

Spinocerebellar Degenerations |

Machado-Joseph Disease |

0.84 |

|

5 |

Spinocerebellar Ataxias |

Machado-Joseph Disease |

0.80 |

|

6 |

Machado-Joseph Disease |

Friedreich Ataxia |

0.79 |

|

7 |

Spinocerebellar Degenerations |

Friedreich Ataxia |

0.79 |

|

8 |

Spinocerebellar Ataxias |

Spinocerebellar Degenerations |

0.79 |

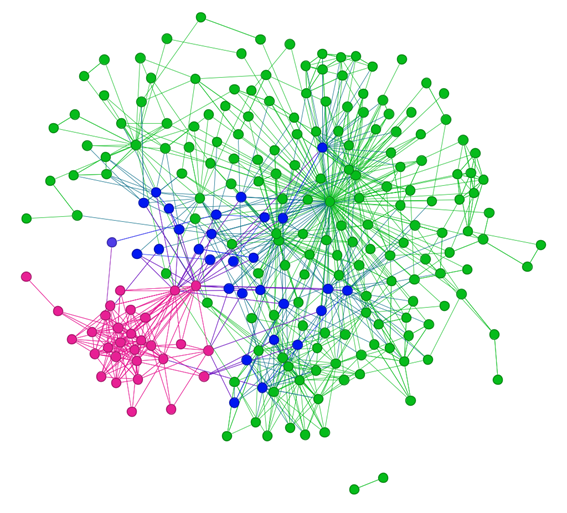

Through integration of drug-disease association data and similarity data, a heterogeneous bipartite drug-disease network was constructed and visualized (Figure 1). It was heterogeneous because two kinds of nodes and three types of edges presented in the network. There were 201 drug nodes in the network, which consisted of 171 anti-cancer drugs and 30 FDA-approved drugs for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Accordingly, another 32 nodes represented different neurodegenerative diseases in the network.

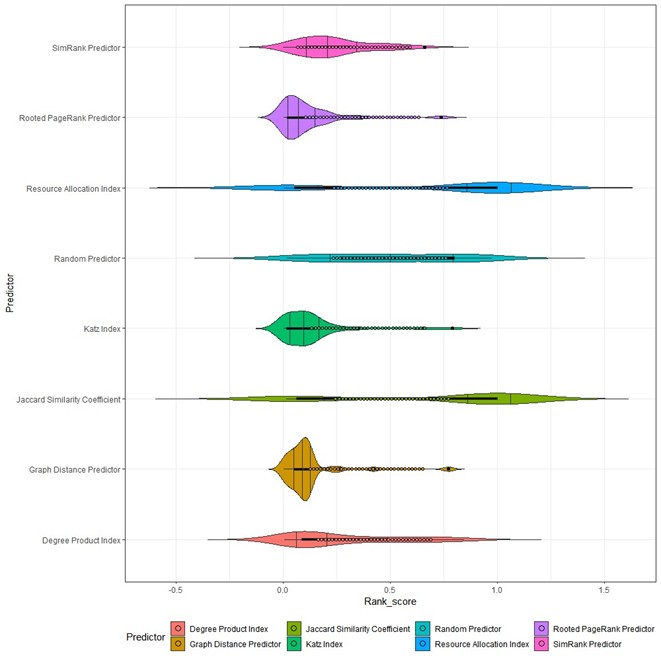

Rooted PageRank performed the best

As described in the method section, different predictors rank scores generated under the Leave-One-Out metric were visualized via violin plot (Figure 2), and their mean values and standard deviations were also calculated and shown in Table 3. The Common neighbors-based predictors, i.e., Jaccard Similarity Coefficient, Resource Allocation Index, and Degree Product Index had greater fluctuation in their rank scores, which indicated their desirable and unstable predictive performances. And compared with Degree Product Index, the Jaccard Similarity Coefficient and Resource Allocation Index’s fluctuations were more obvious. The Random predictor generated random scores in the prediction, which served as a random reference to other predictors’ results. The rest 3 predictors, i.e., SimRank Predictor, Graph Distance Predictor, and Rooted PageRank Predictor, had the relatively better performance that other predictors. Amongst, the Rooted PageRank has the smallest average rank score and standard deviation (Figure 2 and Table 3), and hence it has been considered the best predictors.

|

Link predictor |

Mean value ± standard deviation of rank scores |

|

Jaccard Similarity Coefficient |

0.69±0.45 |

|

Resource Allocation Index |

0.68±0.47 |

|

Degree Product Index |

0.27±0.26 |

|

Katz Index |

0.14±0.17 |

|

Graph Distance Predictor |

0.12±0.14m |

|

Rooted PageRank Predictor |

0.11±0.14 |

|

SimRank Predictor |

0.16±0.21 |

|

Random Predictor |

0.50±0.32 |

Rooted PageRank algorithm scored the best mean and standard deviation in terms of predictive performance. Graph Distance Predictor has a very close performance, but its rank score mean value was slightly larger than that of the Rooted PageRank Predictor (Table 3), indicating that, the Graph distance predictor’s overall performance failed to outperform Rooted PageRank’s. And therefore, Rooted PageRank predictor was the better method for current network dataset.

Drug-disease link prediction

Using the best predictor, Rooted PageRank, the probable links between drug nodes and disease nodes were predicted. The top-ranked hits were selected and listed in Table 4. Three anti-cancer drugs were predicted to be effective for postherpetic neuralgia. They were Vincristine, Vincristine sulfate, and Vinblastine. For these predictive therapeutic results, relevant literature supports were found. Other predictive results were, Venetoclax for Parkinson’s disease, and Oblimersen sodium for Parkinson’s disease, Parkinsonian disorder, and Alzheimer’s disease.

|

Neurodegenerative disease |

Anti-cancer drug |

Description |

Reference of anti-neurodegeneration study of relevant anti-cancer drug |

|

Postherpetic neuralgia |

Vincristine |

Preventing tublin aggregations and disrupting metaphase in cell cycle. It is used to treat leukemia, neuroblastoma, Hodgkin’s disease, etc. |

Dowd et al., 1999 [45] |

|

Vincristine Sulfate |

Sulfate salt of Vincristine. With better bioavailability and pharmacokinetic features than Vincristine. |

Mora et al., 2016 [46] |

|

|

Vinblastine |

Vinca alkaloid of Vincristine. Has similar anti-cancer mechanisms to Vincristine. Used to treat brain cancer, melanoma and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, etc. |

Opavsky et al., 1989 [47] |

|

|

Parkinson’s disease |

Venetoclax |

Venetoclax weakens the survival of cancer cells via targeting and blocking Bcl-2 protein’s functions. It is used to treat lymphoma and leukemia. Side effects exist. |

|

|

Oblimersen sodium |

It is a bcl-2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide. It targets Bcl-2 mRNA, inhibits the formation of Bcl protein and hence weakens the survival of cancer cells. It is used to treat breast cancer, lymphoma, etc. |

|

|

|

Alzheimer’s disease |

Oblimersen sodium |

Same as above. |

|

|

Parkinsonian disorder |

Oblimersen sodium |

Same as above. |

|

|

A part of the predictive top-hits have the supporting evidence from literature and reports. |

|||

Postherpetic neuralgia is a kind of persistent nerve pain resulting from shingles and herpes varicella-zoster virus. The patients of it are with main symptoms of headaches, numbness, pain, burning, etc [48]. According to our predictive results, 3 anti-cancer drugs were predicted to have potential treatment effects on the postherpetic neuralgia. They are Vincristine, Vincristine sulfate, and Vinblastine (Table 4). Vinblastine is an anti-cancer drug of tubulin modulator. It is used for generalized Hodgkin’s disease, lymphocytic lymphoma, breast cancer, neuroblastoma, etc. In fact, according to literature review, there is already report about the usage of Vinblastine to treat the postherpetic neuralgia [47]. This is a literature evidence which indicates the good performance and predictive power of our method. For the other two predicted anti-cancer drugs, the Vincristine sulfate is the sulfate salt of Vincristine, and Vincristine sulfate is used to treat neoplasms and lymphoma. Vincristine is used to treat acute lymphocytic leukemia and etc. While due to poor oral bioavailability, Vincristine was formulated to become Vincristine sulfate so as to obtain better pharmacokinetic results [46]. Interestingly, Vincristine was also reported to be used for trying to cure postherpetic neuralgia patients [45]. This is another supporting evidence of the good predictive power of our prediction framework.

Discussion

Neurodegenerative disorders pose a significant global challenge because of the brain's immense complexity, which makes in-depth research difficult. We've also observed that some neurodegenerative conditions are rare diseases, often receiving minimal research attention. Examples include Lewy body disease and Huntington's disease. Currently, a substantial number of individuals suffer from complex or rare diseases due to a lack of effective treatment.

The traditional drug discovery approach for neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer's disease, has often fallen short. This highlights the urgent need for alternative strategies. With an increasing number of approved drugs showing effects on additional molecular targets or therapeutic uses, it's a smart move to explore disease-oriented drug repositioning, especially when conventional methods struggle with hard-to-study and hard-to-treat diseases.

Drug repositioning offers several benefits over developing new drugs from scratch (i.e., the de novo drug discovery and development approach), such as lower costs in terms of time and resources. These advantages, along with the success rate of repositioning, can be further boosted by computational analytics. For instance, large-scale computational data screening and analysis can help select high-potential drug candidates, thereby saving resources and costs by reducing the number of chemicals needing experimental testing. Furthermore, computational predictive analyses, like machine learning, can forecast whether chemicals and biomolecules will interact effectively. These computational approaches are becoming increasingly vital and significant in drug repositioning efforts.

In the predictive results of this work, Venetoclax used for treating chronic lymphocytic leukemia was predicted to have potential treatment effect on the Parkinson’s disease. As an anti-cancer drug, Venetoclax works via selective suppression on Bcl-2, an anti-apoptotic protein. Bcl-2 in fact exists in wide range of cell types, including the neural cells [49–51]. And the apoptosis is one of the possible reasons causing neurodegenerative disease including the Parkinson’s disease. Potential associations may exist between Venetoclax and the Parkinson’s disease via Bcl-2 regulations and apoptotic processes. Another anti-cancer drug for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma, i.e., the Oblimersen sodium, was also predicted to associate with the Alzheimer’s diseases, the Parkinson’s disease and the Parkinsonian disorder. Similar to Venetoclax, Oblimersen sodium is also a Bcl-2 modulatory protein, and it works via the anti-sense mechanisms and regulations of the cellular apoptotic processes [52]. It is likely that, through such apoptosis regulatory mechanisms, aforementioned 3 kinds of neurodegenerative diseases could be modulated by Oblimersen sodium. Furthermore, molecular modelling methods such as molecular docking analysis are good in silico way to further analyze the molecular binding interaction models of drug-target pairs, which could be likely to provide support for our prediction. However, neither the Alzheimer’s disease nor the Parkinson’s disease has the clear or confirmed drug target, which gives difficulty to conduct the molecular docking analysis of predicted drug-target association pairs.

While our network analysis successfully identified several anti-cancer drugs with potential for treating neurodegenerative diseases, further validation is crucial. We need to conduct in vitro and in vivo experiments to confirm these predicted therapeutic effects.

Additionally, exploring other link prediction methods is a valuable next step. Every method has its strengths and weaknesses, and no single one is perfect. For instance, machine learning and community-based link prediction methods offer a variety of predictors with different underlying principles. Applying these diverse predictors could lead to the discovery of even more promising drug repurposing opportunities.

Conclusions

This research explored a novel strategy to identify anti-cancer drugs with potential for treating neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer's. We built a heterogeneous bipartite drug-disease network by analyzing similarities between drug pairs and disease pairs. We then applied and evaluated eight different prediction methods on this network. Through rigorous testing using a leave-one-out strategy and rank scores, Rooted PageRank emerged as the most effective predictor. We used Rooted PageRank to identify anti-cancer drugs likely to have therapeutic effects on neurodegenerative diseases. Our computational and predictive analyses uncovered several high-potential drug-disease associations, including Vincristine-Postherpetic neuralgia and Oblimersen sodium-Alzheimer's disease. We found further literature evidence supporting these predictions.

Ultimately, this work demonstrates a successful computational and systems biology approach for drug repurposing, identifying existing anti-cancer drugs as promising candidates for treating neurodegenerative conditions.

Data Availability

Dataset of this study would be available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author: Dr. Hui-Heng Lin.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding Statement

This work received support from Ernst Mach Program (Grant ID: ICM-2018-10230), Österreichs Agentur für Bildung und Internationalisierung, OeAD, Wien, Österreich.

Acknowledgments

This work was kindly supported by multiple researchers and scholars from Viennese research institutions, including but not limited to the following kind supporters: the Univ.-Prof. Dr. Wolf-Dieter Rausch from the Eurasia-Pacific Uninet and Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien, the Dr. David Philip Kreil and Dr. Maciej Kandula from Universität für Bodenkultur, the Dr. Stefan Thurner and Dr. Peter Klimek from Die Medizinische Universität Wien, the Dr. Markus Strauss from the Complexity Science Hub Vienna, and the Dr. Thomas Scherngell from AIT Austrian Institute of Technology GmbH.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1 shows U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved drugs for treating different neurodegenerative diseases.

References

2. de Lau LM, Breteler MM. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Jun;5(6):525–35.

3. Marsh JL, Lukacsovich T, Thompson LM. Animal models of polyglutamine diseases and therapeutic approaches. J Biol Chem. 2009 Mar 20;284(12):7431–5.

4. Thompson LM. Neurodegeneration: a question of balance. Nature. 2008 Apr 10;452(7188):707–8.

5. Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA. Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1989 Oct;3(4):519–26.

6. Hamley IW. The amyloid beta peptide: a chemist's perspective. Role in Alzheimer's and fibrillization. Chem Rev. 2012 Oct 10;112(10):5147–92.

7. Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006 Oct 19;443(7113):787–95.

8. Bredesen DE, Rao RV, Mehlen P. Cell death in the nervous system. Nature. 2006 Oct 19;443(7113):796–802.

9. Hardy J, Allsop D. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1991 Oct;12(10):383–8.

10. Mudher A, Lovestone S. Alzheimer's disease-do tauists and baptists finally shake hands? Trends Neurosci. 2002 Jan;25(1):22–6.

11. Uenaka K, Nakano M, Willis BA, Friedrich S, Ferguson-Sells L, Dean RA, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, safety, and tolerability of the amyloid β monoclonal antibody solanezumab in Japanese and white patients with mild to moderate alzheimer disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2012 Jan-Feb;35(1):25–9.

12. Wischik CM, Bentham P, Wischik DJ, Seng KM. O3‐04–07: Tau aggregation inhibitor (TAI) therapy with rember™ arrests disease progression in mild and moderate Alzheimer's disease over 50 weeks. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2008 Jul;4: T167.

13. Harrington C, Rickard JE, Horsley D, Harrington KA, Hindley KP, Riedel G, et al. O1‐06–04: Methylthioninium chloride (MTC) acts as a Tau aggregation inhibitor (TAI) in a cellular model and reverses Tau pathology in transgenic mouse models of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2008 Jul;4: T120–1.

14. Wendler A, Wehling M. Translatability scoring in drug development: eight case studies. J Transl Med. 2012 Mar 7;10:39.

15. Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 2016 Sep 1;537(7618):50–6.

16. Servick K. Another major drug candidate targeting the brain plaques of Alzheimer’s disease has failed. What’s left. Science. 2019 Mar;10.

17. Kitaoka K, Shimizu N, Ono K, Chikahisa S, Nakagomi M, Shudo K, et al. The retinoic acid receptor agonist Am80 increases hippocampal ADAM10 in aged SAMP8 mice. Neuropharmacology. 2013 Sep;72:58–65.

18. Monacelli F, Cea M, Borghi R, Odetti P, Nencioni A. Do Cancer Drugs Counteract Neurodegeneration? Repurposing for Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;55(4):1295–306

19. Hayes CD, Dey D, Palavicini JP, Wang H, Patkar KA, Minond D, et al. Striking reduction of amyloid plaque burden in an Alzheimer's mouse model after chronic administration of carmustine. BMC Med. 2013 Mar 26;11:81.

20. Lanza V, Milardi D, Di Natale G, Pappalardo G. Repurposing of Copper(II)-chelating Drugs for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2018 Feb 12;25(4):525–39.

21. Musicco M, Adorni F, Di Santo S, Prinelli F, Pettenati C, Caltagirone C, et al. Inverse occurrence of cancer and Alzheimer disease: a population-based incidence study. Neurology. 2013 Jul 23;81(4):322–8.

22. Roe CM, Behrens MI, Xiong C, Miller JP, Morris JC. Alzheimer disease and cancer. Neurology. 2005 Mar 8;64(5):895–8.

23. Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000 Jan 1;28(1):27–30.

24. Piñero J, Queralt-Rosinach N, Bravo À, Deu-Pons J, Bauer-Mehren A, Baron M, et al. DisGeNET: a discovery platform for the dynamical exploration of human diseases and their genes. Database (Oxford). 2015 Apr 15;2015: bav028.

25. Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger JS, Bocchini CA, McKusick VA. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005 Jan 1;33(Database issue):D514–7.

26. Yang Y, Xu C, Liu X, Xu C, Zhang Y, Shen L, et al. NDDVD: an integrated and manually curated Neurodegenerative Diseases Variation Database. Database (Oxford). 2018 Jan 1;2018: bay018.

27. Wishart DS, Knox C, Guo AC, Shrivastava S, Hassanali M, Stothard P, et al. DrugBank: a comprehensive resource for in silico drug discovery and exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006 Jan 1;34(Database issue): D668–72.

28. Gaulton A, Bellis LJ, Bento AP, Chambers J, Davies M, Hersey A, et al. ChEMBL: a large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 Jan;40(Database issue): D1100–7.

29. Bolton EE, Wang Y, Thiessen PA, Bryant SH. PubChem: integrated platform of small molecules and biological activities. In Annual reports in computational chemistry 2008 Jan 1 (Vol. 4, pp. 217-241). Elsevier., 2008. 217–41.

30. Cao Y, Charisi A, Cheng LC, Jiang T, Girke T. ChemmineR: a compound mining framework for R. Bioinformatics. 2008 Aug 1;24(15):1733–4.

31. Lipkus AH. A proof of the triangle inequality for the Tanimoto distance. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry. 1999 Oct;26(1):263–5.

32. Li M, Peng N. Integration of Disease Similarity Methods. School of Information Science and Engineering, Central South University, Changsha, China;2016.

33. Hamers L, Hemeryck Y, Herweyers G, Janssen M, Keters H, Rousseau R, et al. Similarity measures in scientometric research: The Jaccard index versus Salton's cosine formula. Inf. Process. Manag. 1989 May 1;25(3):315–8.

34. Zhou T, Lü L, Zhang YC. Predicting missing links via local information. The European Physical Journal B. 2009 Oct;71(4):623–30.

35. Newman ME. Clustering and preferential attachment in growing networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2001 Aug;64(2 Pt 2):025102.

36. Barabasi AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999 Oct 15;286(5439):509–12.

37. Katz L. A new status index derived from sociometric analysis. Psychometrika. 1953 Mar;18(1):39–43.

38. Jeh G, Widom J. Simrank: a measure of structural-context similarity. In: Proceedings of the eighth ACM SIGKDD international conference on Knowledge discovery and data mining. ACM, 2002.

39. Jaber M, Papapetrou P, Helmer S, Wood PT. Using time-sensitive rooted pagerank to detect hierarchical social relationships. In: International Symposium on Intelligent Data Analysis. Springer, Cham, 2014.

40. Egghe L, Rousseau R. A measure for the cohesion of weighted networks. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2003 Feb 1;54(3):193–202.

41. Lü L, Zhou T. Link prediction in complex networks: A survey. Physica A: statistical mechanics and its applications. 2011 Mar 15;390(6):1150–70.

42. Page L, Brin S, Motwani R, Winograd T. The PageRank citation ranking: Bringing order to the web. Stanford infolab; 1999 Nov 11.

43. Li P, Liu H, Yu JX, He J, Du X. Fast single-pair simrank computation. In: Proceedings of the 2010 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining. 2010 Apr 29.

44. Kearns M, Ron D. Algorithmic stability and sanity-check bounds for leave-one-out cross-validation. Neural Comput. 1999 Aug 15;11(6):1427–53.

45. Dowd NP, Day F, Timon D, Cunningham AJ, Brown L. Iontophoretic vincristine in the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia: a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999 Mar;17(3):175–80.

46. Mora E, Smith EM, Donohoe C, Hertz DL. Vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy in pediatric cancer patients. Am J Cancer Res. 2016 Nov 1;6(11):2416–30.

47. Opavský J, Pĕnicková V, Jezdinský J. Iontoforetická aplikace vinblastinu k ovlivnĕní refrakterních korenových bolestí a postherpetické neuralgie [Iontophoretic administration of vinblastine in the control of refractory spinal root pain and postherpetic neuralgia]. Cas Lek Cesk. 1989 May 5;128(19):590–4.

48. Johnson RW, Rice AS. Clinical practice. Postherpetic neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 2014 Oct 16;371(16):1526–33.

49. Davids MS, Letai A. ABT-199: taking dead aim at BCL-2. Cancer Cell. 2013 Feb 11;23(2):139–41.

50. Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013 Feb;19(2):202–8.

51. King AC, Peterson TJ, Horvat TZ, Rodriguez M, Tang LA. Venetoclax: A First-in-Class Oral BCL-2 Inhibitor for the Management of Lymphoid Malignancies. Ann Pharmacother. 2017 May;51(5):410–6.

52. Melnikova I, Golden J. Apoptosis-targeting therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004 Nov;3(11):905–6.