Abstract

Brucellosis is a zoonosis in which hepatic involvement is common but usually mild. Acute liver failure and acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) are rarely attributed to brucellosis, and even more rarely to people living with HIV (PLWH). We describe a 50-year-old man from Ghana with newly diagnosed advanced HIV infection and HBV reactivation (anti-HBc IgG positive, anti-HBc IgM negative) who developed ACLF shortly after starting antiretroviral therapy (ART). After an initial viro-immunological response to a bictegravir-based regimen, he experienced a paradoxical deterioration of liver function and was evaluated for liver transplantation. During this phase, he developed painful swelling of the left neck; imaging revealed osteo-articular and muscular lesions. Serology (Wright 1:320) was positive, blood cultures were negative and Brucella PCR was not available; therefore, disseminated brucellosis was considered probable based on serology, compatible clinical syndrome and complete response to anti-Brucella therapy. Targeted treatment with intravenous gentamicin plus oral doxycycline, with maintenance of ART, led to improvement of liver function, resolution of lesions and avoidance of transplantation. Based on timing, viro-immunological response and exclusion of alternative causes, we interpret this ACLF as likely precipitated by disseminated brucellosis in the setting of an unmasking immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Brucellosis should be considered as a potentially reversible cause of ACLF in PLWH from endemic areas, particularly soon after ART initiation.

Keywords

Brucellosis, Acute-on-chronic liver failure, HIV infection, HBV co-infection, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, Case report

Introduction

Brucellosis is a widespread zoonosis caused by Gram-negative intracellular coccobacilli of the genus Brucella, transmitted mainly through unpasteurized dairy products or occupational contact with infected animals [1]. Liver involvement, with hepatomegaly and mild elevation of aminotransferases, is frequent, but severe acute liver failure is distinctly uncommon [1,2]. Only isolated reports describe acute liver failure or ACLF attributable to brucellosis, including adult and pediatric cases and a recent description of severe liver injury with disseminated intravascular coagulation [3–5].

Coinfection with HIV adds complexity, as advanced immunosuppression may favor persistent or atypical infection, while immune reconstitution after ART can precipitate exaggerated inflammatory responses. Brucellosis is not considered a classic opportunistic infection in HIV, and an early European series suggested that it was rarely reported in PLWH and usually occurred in patients with relatively preserved CD4 counts [6]. In contrast, sero-epidemiological studies from endemic areas, such as Iran, have shown higher Brucella seroprevalence in PLWH than in HIV-negative controls, with a proportion of patients having high antibody titers but only mild or absent symptoms [7,8].

ACLF is recognized as a distinct clinical syndrome characterized by acute deterioration of liver function in patients with chronic liver disease or significant hepatic vulnerability, associated with organ failures and high short-term mortality [9,10]. Infections are well-established precipitants of ACLF. We report a case of ACLF likely precipitated by disseminated brucellosis in a patient with advanced HIV disease and acute HBV infection shortly after starting ART, and discuss the possible role of IRIS.

Case Report

A 50-year-old man from Ghana, living in Italy, presented with a 2-week history of epigastric pain, vomiting, asthenia and jaundice. He denied alcohol misuse, hepatotoxic drug intake or known chronic liver disease. Laboratory tests showed marked hepatocellular injury (aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase >1000 U/L), total bilirubin 2.9 mg/dL and international normalized ratio (INR) 2.07, with a Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 20. Serology was consistent with HBV infection and HBV DNA was 1.31×10^8 IU/mL. Anti-HBc IgG was positive and anti-HBc IgM was negative, supporting HBV reactivation rather than acute HBV infection; anti-HDV and anti-HCV were negative and anti-HAV IgG was positive. Screening for HIV was positive, with HIV-RNA approximately 4,070,000 copies/mL and CD4 count 14 cells/µL, fulfilling criteria for advanced HIV disease.

|

Day/month |

24/03 |

3/04 |

24/04 |

2/05 |

14/05 |

24/05 |

1/06 |

10/06 |

18/06 |

1/07 |

12/07 |

31/07 |

9/08 |

27/08 |

13/09 |

24/09 |

|

HIV RNA (copies/mL) |

4,070,000 |

|

|

1710 |

|

|

374 |

|

|

|

1390 |

|

|

|

293 |

|

|

CD 4 (cell/ul) |

14 |

|

104 |

|

|

|

115 |

|

|

|

181 |

161 |

|

186 |

153 |

|

|

HBV DNA (IU/mL) |

131,000,000 |

|

|

|

681 |

|

560 |

|

|

|

< 10 |

|

|

|

|

<10 |

|

AST (U/L) |

1335 |

423 |

879 |

989 |

890 |

330 |

94 |

68 |

68 |

47 |

57 |

46 |

48 |

36 |

45 |

55 |

|

ALT (U/L) |

1781 |

666 |

637 |

721 |

679 |

288 |

81 |

52 |

35 |

26 |

31 |

24 |

29 |

19 |

25 |

33 |

|

Bilirubin (mg/dl) |

2.9 |

4 |

8.9 |

8.9 |

8.2 |

8.2 |

9 |

7.8 |

5.8 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

4.1 |

4.9 |

2.6 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

|

INR |

2.07 |

1.69 |

1.57 |

|

2.69 |

3.1 |

3.74 |

3.44 |

3.44 |

3.04 |

2.79 |

2.52 |

2.8 |

1.91 |

1.81 |

1.59 |

|

Albumin (g/dL) |

4.3 |

2.9 |

|

2.5 |

1.9 |

2.1 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.6 |

3.1 |

3.3 |

2.4 |

2.5 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.3 |

|

Antithrombin III(%) |

50 |

|

|

|

3 |

|

22 |

14 |

26 |

|

21 |

26 |

|

43 |

18 |

30 |

|

V factor (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

20 |

16 |

17 |

13 |

|

22 |

27 |

|

|

45 |

49 |

|

Cholinesterase(U/L) |

13020 |

6164 |

|

2586 |

1769 |

1730 |

<1500 |

<1500 |

<1500 |

<1500 |

<1500 |

<1500 |

|

1547 |

2004 |

2525 |

|

Creatinine mg/dL) |

1.2 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

1 |

1 |

1.4 |

1.4 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

|

Platelets (106/uL) |

166 |

163 |

109 |

98 |

72 |

87 |

87 |

117 |

87 |

72 |

58 |

61 |

49 |

70 |

64 |

73 |

Figure 1. Therapeutic timeline from admission to last follow-up.

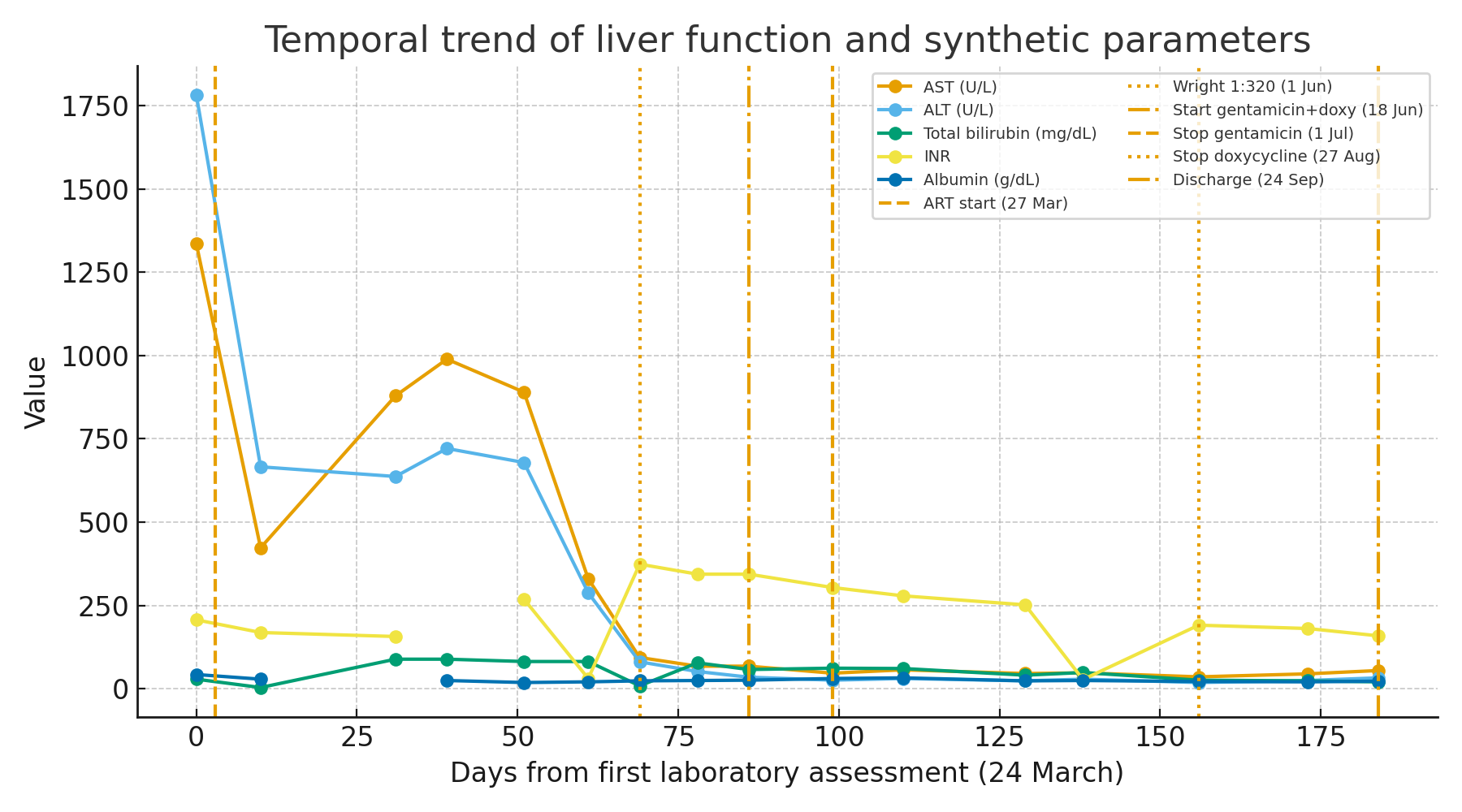

Figure 2. Temporal trend of liver function and synthetic parameters.

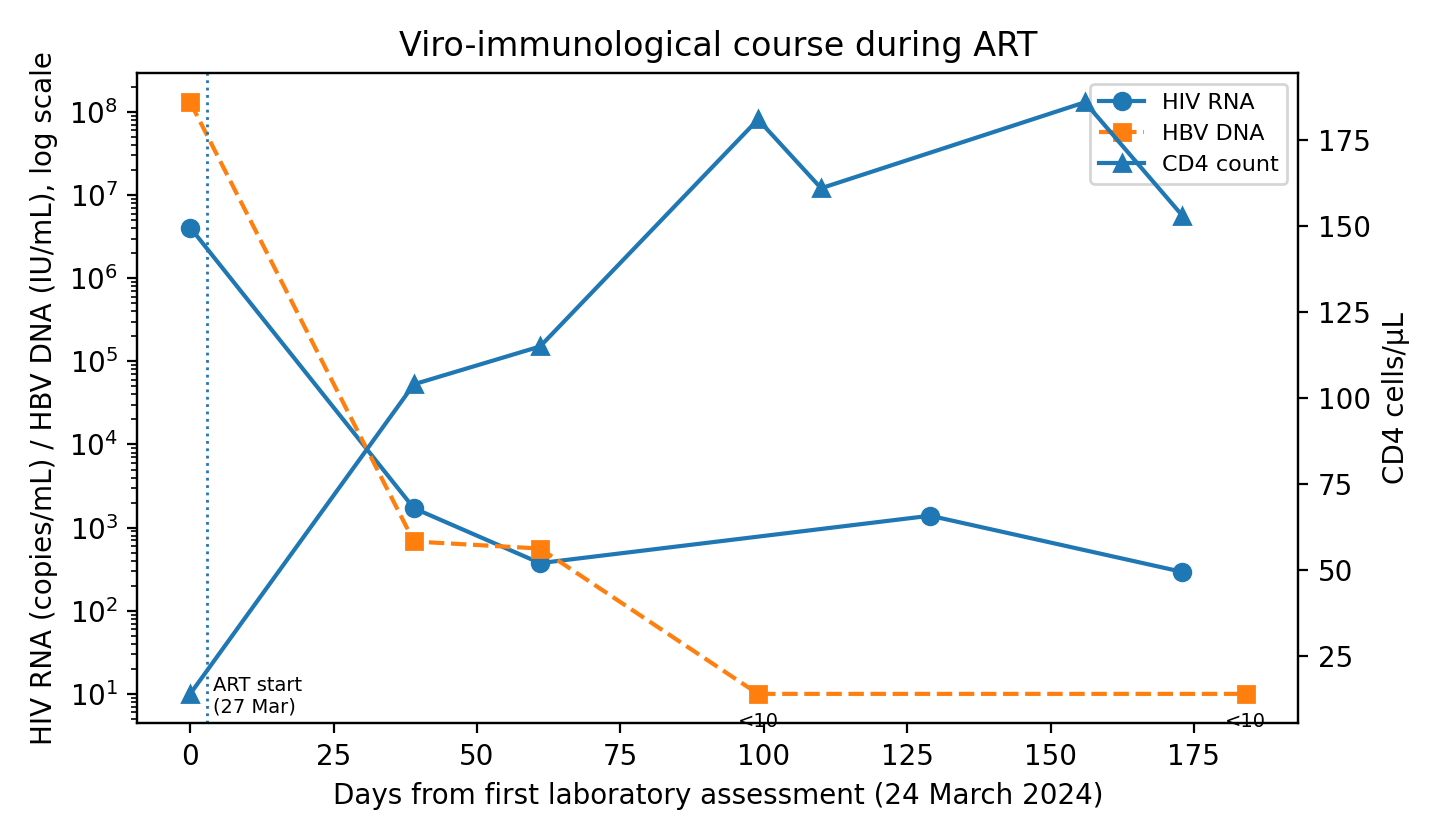

Figure 3. Viro-immunological course during ART.

A few days after admission, ART was started with a fixed-dose combination of bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide in order to treat both HIV and HBV. In the first weeks of therapy, HIV-RNA and HBV DNA declined by several logs, while CD4 count rose above 100 cells/µL and liver enzymes decreased, suggesting partial biochemical improvement.

About two months after ART initiation, the patient developed progressive jaundice, worsening coagulopathy and hypoalbuminemia, with bilirubin peaking at 9 mg/dL, INR up to 3.7 and MELD score 28, consistent with ACLF. Liver transplantation was considered.

During this paradoxical deterioration, the patient developed painful swelling in the left laterocervical region. Imaging revealed an abscess involving the sternocleidomastoid and pectoral muscles with sternoclavicular arthritis and osteomyelitis. Empirical antibiotic therapy with meropenem and linezolid was started, but blood cultures remained negative. Standard serology showed a Wright agglutination titer of 1:320, and this was considered highly suggestive of disseminated brucellosis in the context of a compatible clinical-radiological syndrome; Brucella PCR was not available. Targeted therapy was initiated with intravenous gentamicin 3 mg/kg/die for 13 days combined with oral doxycycline 100 mg BID for 8 weeks. Rifampicin was avoided because of potential pharmacokinetic interactions with bictegravir. ART was maintained without modification. After starting anti-Brucella therapy, liver function progressively improved, with decreasing bilirubin and INR and rising albumin; the MELD score fell to 17 at discharge. Osteo-articular lesions regressed radiologically and clinically. At follow-up, HIV-RNA and HBV DNA were suppressed, and CD4 count continued to increase, with no relapse of brucellosis.

Discussion

This case illustrates an uncommon but clinically important cause of ACLF in a patient with advanced HIV disease and HBV infection. Although liver involvement is frequent in brucellosis, most patients develop only mild biochemical abnormalities or hepatomegaly [1,2]. Severe acute liver failure or ACLF due to brucellosis has been described only in isolated reports, including adult and pediatric cases and one case of severe liver injury associated with disseminated intravascular coagulation [3–5]. In our patient, ACLF arose in close temporal association with disseminated brucellosis and improved promptly after targeted therapy without changes to ART, supporting a contributory role for Brucella.

The immunobiology of brucellosis provides a plausible mechanism. Control of Brucella infection depends mainly on a Th1-type, cell-mediated immune response that activates macrophages to clear intracellular bacteria through interleukin-12, interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α [1,11,12]. Advanced HIV infection, with profound CD4+ T-cell depletion impairs this response and may allow brucellosis to remain subclinical or paucisymptomatic. When effective ART is started, rapid viral suppression and immune recovery can unmask such infections and trigger an exaggerated inflammatory reaction, recognized as IRIS. Suggested diagnostic criteria for IRIS include recent initiation of ART, documented viro-immunological response, new or worsening inflammatory manifestations of an infection and lack of a better alternative explanation. Our patient fulfilled these criteria and improved with specific anti-Brucella therapy while continuing ART, making an unmasking brucellosis IRIS a plausible explanation; drug-induced liver injury and HBV flare were less consistent with the overall clinical and virological picture.

Brucellosis is rarely reported in PLWH and is not an AIDS-defining condition. A European case series described brucellosis in HIV-infected patients with relatively preserved CD4 counts and outcomes similar to HIV-negative individuals [6]. In contrast, sero-epidemiological studies in endemic areas have found higher Brucella seroprevalence in PLWH than in HIV-negative controls, with a subset of patients showing high antibody titers but few or no symptoms [7,8]. Taken together, these observations suggest that brucellosis in HIV may be underdiagnosed rather than truly rare, particularly in regions where zoonotic exposure is common. To our knowledge, brucellosis-associated ACLF in advanced HIV disease with concomitant HBV infection and probable unmasking IRIS has not been previously reported.

ACLF is increasingly recognized as a syndrome in which acute insults, often infectious, precipitate organ failures and high short-term mortality in patients with underlying hepatic vulnerability [9,10]. In this context, identifying reversible or treatable triggers is crucial. Our case highlights that zoonotic infections such as brucellosis may represent one such trigger, especially in migrants or travellers from endemic areas. From a practical standpoint, clinicians should consider brucellosis in the differential diagnosis of unexplained ACLF in PLWH shortly after ART initiation, and standard anti-Brucella regimens can be used with careful attention to drug–drug interactions, while continuing ART whenever possible.

Conclusion

Brucellosis should be recognized as a potentially reversible cause of ACLF in patients with advanced HIV infection, particularly in those from endemic areas and in the early months after ART initiation. Early suspicion, serological testing and prompt targeted therapy may prevent liver transplantation and improve outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical Approval

According to the policy of the AORN dei Colli – Cotugno Hospital, single anonymized case reports do not require formal approval by the local Ethics Committee.

References

2. Ozturk-Engin D, Erdem H, Gencer S, Kaya S, Baran AI, Batirel A, et al. Liver involvement in patients with brucellosis: results of the Marmara study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014 Jul;33(7):1253–62.

3. García Casallas JC, Villalobos Monsalve W, Arias Villate SC, Fino Solano IM. Acute liver failure complication of brucellosis infection: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2018 Mar 9;12(1):62.

4. Çakar S, Eren G, Gülfidan G, Ömür Ecevit Ç, Bekem Ö. First Pediatric Case Report of an Acute Liver Failure as a Complication of Brucellosis. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2021 Nov 11;10(10):975–6.

5. Zhang W, Xu F, Zheng Q, Dong X. Brucellosis complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation and liver injury: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2025 Oct 14;25(1):1307.

6. Moreno S, Ariza J, Espinosa FJ, Podzamczer D, Miró JM, Rivero A, et al. Brucellosis in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998 May;17(5):319–26.

7. Abdollahi A, Morteza A, Khalilzadeh O, Rasoulinejad M. Brucellosis serology in HIV-infected patients. Int J Infect Dis. 2010 Oct;14(10):e904–6.

8. Hajiabdolbaghi M, Rasoulinejad M, Abdollahi A, Paydary K, Valiollahi P, SeyedAlinaghi S, et al. Brucella infection in HIV infected patients. Acta Med Iran. 2011;49(12):801–5.

9. Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013 Jun;144(7):1426–37, 1437.e1–9.

10. Arroyo V, Moreau R, Jalan R, Ginès P; EASL-CLIF Consortium CANONIC Study. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: A new syndrome that will re-classify cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2015 Apr;62(1 Suppl):S131–43.

11. de Figueiredo P, Ficht TA, Rice-Ficht A, Rossetti CA, Adams LG. Pathogenesis and immunobiology of brucellosis: review of Brucella-host interactions. Am J Pathol. 2015 Jun;185(6):1505–17.

12. Skendros P, Boura P. Immunity to brucellosis. Rev Sci Tech. 2013 Apr;32(1):137–47.