Abstract

Objectives: Anemia is a frequent extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and has been linked to increased disease activity and poorer outcomes. This study aimed to evaluate the association between hemoglobin (Hb) levels and RA disease activity in a Middle Eastern population.

Methods: A retrospective observational study was conducted using data from the Kuwait Registry for Rheumatic Diseases (KRRD), which includes adult RA patients meeting the ACR/EULAR criteria. Clinical and laboratory data were collected from six government hospitals across Kuwait between February 1, 2013, and February 1, 2023. Disease activity was assessed using DAS28, CDAI, and SDAI scores. Anemia was defined by WHO criteria (Hb <13 g/dL in males and <12 g/dL in females).

Results: Of the 1,968 registered patients, 1,775 were included in the final analysis. Anemia was present in 48.5% (n=860) of patients. Anemic individuals had significantly higher DAS28 and CDAI scores compared to those with normal Hb (p<0.001 and p=0.002, respectively), and higher HAQ disability scores (p<0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that anemia was independently associated with joint swelling, high HAQ scores, joint deformities, and positive anti-CCP titers.

Conclusion: This large population-based study from Kuwait confirms a strong association between low hemoglobin levels and higher RA disease activity. Monitoring anemia may offer additional insight into disease severity and guide more targeted RA management strategies in Middle Eastern populations.

Keywords

Anemia, Rheumatoid arthritis, DAS28, Kuwait, Middle East and North Africa

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune condition characterized by progressive destructive synovial joint inflammation. The global prevalence of RA in the adult population ranges from 0.3 to 1% [1]. Within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, the reported prevalence of RA varies more widely, ranging between 0.06 to 3.4% [2]. RA not only affects physical health, but also impacts patient quality of life, productivity, and places significant pressure on healthcare systems [3,4]. It is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and a major contributor to years lived with disability (YLDs) [3]. In addition, RA is associated with a higher risk of comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and infections due to immunosuppressive treatments [5]. Economically, the burden of RA is substantial, both directly from disease impact and its complications as well as indirect costs such as disability [6]. In step with global trends, the burden of RA has increased in the MENA region over the past 3 decades, highlighting the need for better guidelines to enable effective treatment for RA patients in these countries [7]. Extra-articular involvement is a frequent long-term complication of this disease, and RA-associated anemia is a commonly reported hematological abnormality [4,8]. The prevalence of RA-associated anemia is estimated to range between 7.5% to 47% in Western countries [1,4,8]. It is estimated that up to 60% of the patients with RA develop anemia during their disease course [9]. In the MENA region, the reported prevalence of anemia in RA patients varies widely between 30% to as high as 68% [10–12]. Although anemia of chronic disease is the most common form associated with RA, a few other studies indicate that iron deficiency anemia is more prevalent [13].

Anemia is a common extra-articular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and has been shown to correlate with increased disease activity and a higher burden of complications. Patients with RA-associated anemia often present with more severe disease phenotypes, including elevated disease activity scores, accelerated radiographic joint damage, and greater degrees of structural deformity and functional impairment [14]. Recent cohort studies confirm that low hemoglobin levels are significantly associated with higher disease activity scores such as DAS28 and SDAI, and that anemia prevalence increases with disease severity [14,15]. Despite this well-established association, anemia is not currently incorporated into any of the standard composite scoring systems used to evaluate RA disease activity.

The most widely used tools for assessing RA activity focus primarily on joint involvement, inflammatory markers, and patient-reported outcomes. The Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) evaluates disease severity based on the count of 28 tender and swollen joints, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) level, and a visual analog scale reflecting the patient’s overall health perception [16]. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) similarly incorporates the number of tender and swollen joints, CRP levels, and both patient and physician global assessments [17]. Meanwhile, the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) omits laboratory markers entirely, relying solely on clinical examination and global assessments by both the patient and the evaluator [18].

Recent studies have also suggested that novel hematologic indices such as red cell distribution width (RDW) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) may offer additional insight into disease activity and systemic inflammation in RA [19]. Moreover, some researchers have advocated for integrating hemoglobin or anemia-related markers into composite disease activity scores to better reflect the full systemic impact of the disease [20]. While current scoring systems remain indispensable tools for guiding treatment, their exclusion of anemia may overlook a clinically significant marker of inflammatory burden and disease progression.

There is a significant gap in our understanding of how RA-associated anemia interacts with disease activity, particularly in the MENA populations. This study aims to address this knowledge gap by investigating the relationship between these two factors in a cohort of patients diagnosed with RA in Kuwait. The findings of this study have broader implications for improving the management of RA in the MENA region. By clarifying the impact of anemia on disease activity, healthcare providers can tailor treatments more effectively, potentially leading to better disease outcomes and quality of life for patients. Furthermore, understanding the regional differences in disease manifestation may pave the way for developing more targeted public health strategies, including early diagnosis and personalized therapeutic interventions.

Materials and Methods

Design and participants

In this retrospective observational analysis, we utilized data from the Kuwait Registry for Rheumatic Diseases (KRRD), a longitudinal database of patients diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in Kuwait. The registry includes individuals aged 18 years or older who meet the classification criteria for RA established by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) [21]. Data were collected from six major government hospitals across Kuwait (Al-Amiri Hospital, Al-Farwaniya Hospital, Mubarak Al-Kabir Hospital, Sabah Hospital, Jaber Hospital, and Al-Jahra Hospital) between 1st February 2013 and 1st February 2023. The KRRD collects data through physician-entered electronic forms supplemented by structured patient interviews conducted during routine clinical visits. The questionnaire used in this study was previously published and validated in earlier KRRD studies [22]. All clinical data were recorded by 17 certified rheumatologists participating in the registry. To reduce potential confounding, patients with coexisting autoimmune diseases, malignancies, hematological disorders, or pregnancy were excluded from the analysis.

Basic demographic data and baseline disease characteristics were collected retrospectively from patients attending the rheumatology outpatient department (OPD). This data spanned their clinical and laboratory data, including hemoglobin (Hb), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide-2 (anti-CCP) antibodies, antinuclear antibody titers (ANA), as well as acute phase reactants ESR and CRP levels. The registry did not record mean corpuscular Hb (MCH), mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean corpuscular Hb concentration (MCHC), ferritin, or iron levels and so none of these anemia parameters could be measured. For patients with more than one test result, the mean result was taken. To assess RA disease activity, we used three scoring systems: DAS28, CDAI, and SDAI, in addition to the Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI), a validated tool for assessing functional disability in RA patients, and the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain evaluation (range 0–10 cm). The swollen and tender joint counts were assessed during each rheumatology OPD visit as part of routine clinical evaluation.

The Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ-DI) was used to evaluate functional disability among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. The HAQ-DI assesses 20 activities of daily living across eight areas: dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and common activities. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, where 0 = no difficulty, 1 = some difficulty, 2 = much difficulty, and 3 = unable to do. The highest score in each domain is taken, and the HAQ-DI is calculated as the mean of the eight domain scores, yielding a total score between 0 and 3. Higher scores reflect greater disability. Scores of 0.0–1.0 indicate mild disability, 1.1–2.0 moderate disability, and 2.1–3.0 severe disability. The HAQ-DI has been validated for use in rheumatoid arthritis populations and demonstrates good reliability and sensitivity to change [24,25].

The VAS data were collected at each clinic visit during patient evaluations, typically recorded at baseline (initial visit) and during subsequent follow-up visits scheduled every 3 to 6 months, in line with routine clinical care. All participating patients attended their OPD appointment at least twice during the study period. On each visit, our team collected data including disease activity scores, HAQ-DI, as well as hemoglobin and other laboratory data. The KRRD also gathered comorbidity history as provided by each participating patient, including the presence of coronary artery disease (CAD), bronchial asthma, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, osteoarthritis (OA), osteoporosis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and any thyroid condition (hypo- or hyperthyroidism).

Data pertaining to the KRRD were collected and stored on a secured website linked to the six participating hospitals. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the College of Medicine, University of Kuwait, Kuwait Ministry of Health, and Kuwait Institute for Medical Specializations (KIMS). The ethics approval number was (2016/477). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to data collection.

Medical personnel were trained to complete a standard form, either manually or electronically. The nurses underwent an educational course on RA and intensive training to ascertain tender and swollen joints. Global assessment of disease activity was performed by an outpatient rheumatologist. The methodology used in this study has been previously described in detail [22].

Definitions

Anemia was characterized in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines. An Hb concentration of <13 g/dL in males and <12 g/dL in females was indicative of anemia [23].

The categorization of disease activity levels and the criteria for remission were established as follows: DAS28 scores ranging from 2.6 to 3.2 denoted low activity, 3.2–5.1 moderate activity, >5.1 high activity; and below 2.6 were classified as remission. A SDAI score of 11 or less was considered low, 11–26, >26 as high, and <3.3 as remission. For the CDAI, a score between 2.8 and 10 was low, 10–22 was moderate, >22 was high, and 2.8 or less was remission. These metrics for assessing RA disease activity have been endorsed by the ACR for clinical applications [18].

Statistical analysis

Pertinent data were extracted for statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 29.0 (IBM; Armonk, NY, USA). The data were analyzed descriptively to assess the mean, standard deviation, percentage, and frequency of distribution of the study variables of interest, namely gender, age, disease duration, ESR, and serological markers, such as RF, ANA, and anti-CCP titers. A two-sample t-test was used to evaluate the significance of the differences between means. The chi-squared test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the relationships between categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to determine the association between anemia and various disease parameters and comorbidities.

Results

Patient characteristics

In total, 1,968 patients were registered in the KRRD study between February 2013 and February 2023, of whom 193 were excluded because of incomplete or missing data. Of the remaining 1,775 patients, 65.4% were female. The mean patient age was 56.2±12.6 years. Of these, 52.3% were non-Kuwaitis. Mean disease duration was 11.2 years. The mean Hb level of the participants in the study was 10.7 g/dL. The number of patients with low Hb levels, consistent with the WHO criteria for anemia, was 860 (48.5%). The overall mean Hb level in the anemic group was 7.7±4.7 g/dl (mean Hb 7.7±5 g/dL in men, 7.7±4.5 g/dL in women). In the normal Hb group, 915 RA patients (51.5%) had a mean Hb value of 13.5 g/dL (mean Hb 14.5±1 g/dL in men, 13.1±0.8 g/dL in women). Other blood measures (MCH, MCV, and MCHC), vitamin B12 levels, and iron levels (ferritin and iron levels) were not measured in the KRRD database. The overall characteristics of the anemia and normal Hb groups were comparable. The gender distribution, mean patient age, and disease duration were similar between the groups. Table 1 describes the demographics of our registry by comparing the anemia and non-anemia groups.

|

|

Anemic (N=860) |

Normal (N=915) |

Total (N=1775) |

p value |

|

Gender Female Male |

529.0 (61.5%) 331.0 (38.5%) |

632.0 (69.1%) 283.0 (30.9%) |

1161.0 (65.4%) 614.0 (34.6%) |

< 0.0011 |

|

Age in years Mean (SD) Range |

56.1 (12.8) 17.6–93.7 |

56.4 (12.4) 18.4–88.0 |

56.2 (12.6) 17.6–93.7 |

0.6162 |

|

Disease Duration (years) Mean (SD) Range |

11.3 (7.1) 0.2–53.7 |

11.2 (7.1) 0.2–56.7 |

11.2 (7.1) 0.2–56.7 |

0.6842 |

|

Tobacco smoker |

44 (7.2%) |

87 (11.9%) |

131 (9.8%) |

0.0041 |

|

Creatinine (µmol/L) Mean (SD) Range |

64.7 (29.8) 0.7–602 |

63.3 (18) 3.9–256 |

64 (24.4) 0.7–602 |

0.2572

|

|

Hgb Mean (SD) Range |

77.3 (47.4) 11.0–129.0 |

135.7 (11.2) 120.0–175.0 |

107.4 (44.8) 11.0–175.0 |

< 0.0012 |

|

Comorbidities Asthma Ischemic heart disease Type 2 Diabetes mellitus Hyperlipidemia Hypertension Osteoarthritis Osteoporosis Peptic ulcer disease Hypothyroidism |

91.0 (10.6%) 27.0 (3.1%) 188.0 (21.9%) 92.0 (10.7%) 198.0 (23.0%) 68.0 (7.9%) 61.0 (7.1%) 9.0 (1.0%) 95.0 (11.0%) |

98.0 (10.7%) 27.0 (3.0%) 172.0 (18.8%) 107.0 (11.7%) 196.0 (21.4%) 76.0 (8.3%) 58.0 (6.3%) 22.0 (2.4%) 124.0 (13.6%) |

189.0 (10.6%) 54.0 (3.0%) 360.0 (20.3%) 199.0 (11.2%) 394.0 (22.2%) 144.0 (8.1%) 119.0 (6.7%) 31.0 (1.7%) 219.0 (12.3%) |

0.9301 0.8171 0.1091 0.5061 0.4171 0.7581 0.5251 0.0291 0.1091 |

|

1 Pearson’s Chi-squared test; 2 Linear Model ANOVA; SD: Standard Deviation |

||||

Relationship between Hb levels and RA disease measures

The differences between the anemic and normal Hb groups in terms of RA disease measures, including RA disease activity scores, health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores, antibody levels, acute-phase reactants are shown in Table 2. The anemic group had a statistically significant higher mean ESR (36.9±27.6 mm/h) but not CRP (p<0.0011). In addition, this group had worse disease activity scores than the normal Hb cohort, including DAS28, CDAI, and HAQ scores, indicating higher disease activity in the anemic group. The difference in SDAI disease activity was not statistically significant. Comparison of the levels of RF, anti-CCP antibodies, antinuclear antibody titers, and sicca symptoms revealed no statistically significant differences between the two groups.

|

|

Anemia group |

Normal Hb group |

p value |

|

DAS28 Mean (SD) |

3.0 (1.4) |

2.6 (1.2) |

<0.0011 |

|

CDAI Mean (SD) |

7.6 (10.6) |

6.2 (9.2) |

0.0021 |

|

SDAI Mean (SD) |

7.5 (5.7) |

6.9 (5.4) |

0.0881 |

|

HAQ Mean (SD) |

1.1 (0.7) |

0.9 (0.6) |

<0.0011 |

|

RF positive |

617.0 (77.6%) |

652.0 (77.7%) |

0.9612 |

|

Anti-CCP positive |

449.0 (65.8%) |

486.0 (68.2%) |

0.3552 |

|

ANA positive |

198.0 (29.4%) |

237.0 (33.7%) |

0.0872 |

|

VAS Mean (SD) |

1.9 (2.6) |

1.7 (2.4) |

0.0751 |

|

ESR Mean (SD) |

36.9 (27.6) |

25.4 (18.6) |

<0.0011 |

|

CRP Mean (SD) |

5.1 (5.1) |

4.7 (4.8) |

0.1191 |

|

1 Linear Model ANOVA; 2 Pearson’s Chi-squared test; Hb: Hemoglobin; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; SD: Standard Deviation; DAS28: Disease Activity Score in 28 joints; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; RF: Rheumatoid Factor; Anti-CCP: Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide-2; ANA: Antinuclear Anti-Antibody; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; CRP: C-reactive Protein. |

|||

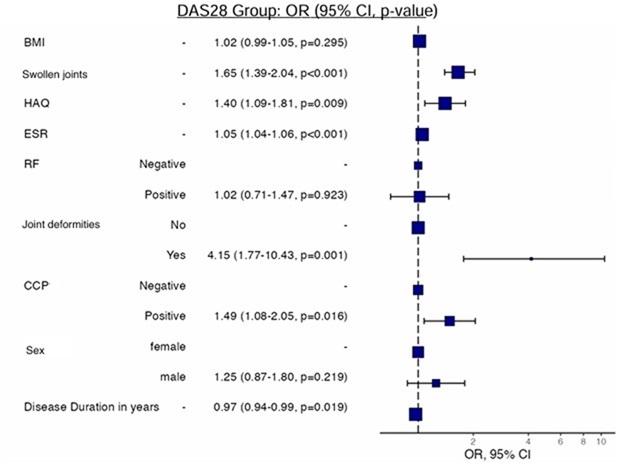

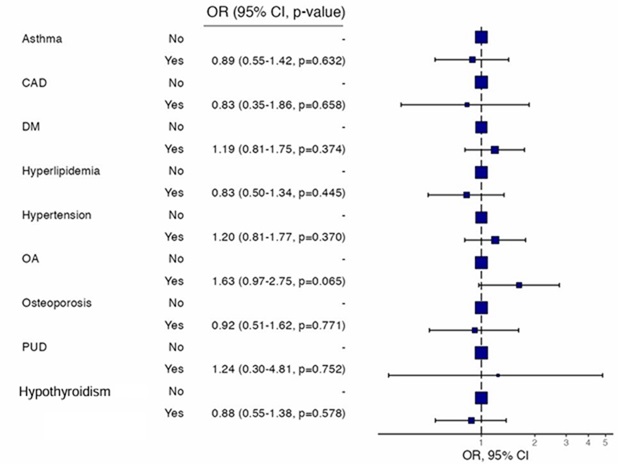

In multivariate analysis, RA patients with the following disease characteristics were associated with anemia: joint swelling, high HAQ scores, associated joint deformities, and positive anti-CCP antibody titers (Figure 1). Our study analyzed the association among patient comorbidities, RA disease activity, and anemia. However, on multivariate analysis, there was no statistically significant relationship between patient comorbidities, disease activity, and low Hb levels (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Multivariate analysis of the association between the probability of anemia and various disease parameters in the KRRD. BMI: Body Mass Index; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; ESR: Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; RF: Rheumatoid Factor; CCP: Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide-2.

Figure 2. Multivariate analysis of the association between the probability of anemia and various comorbidities in the KRRD. CAD: Coronary Arterial Disease; DM: Diabetes Mellitus type 2; OA: Osteoarthritis; PUD: Peptic Ulcer Disease.

The logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify predictors of disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, categorized by Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28) as either low disease activity (DAS28 <3.2) or moderate-to-high disease activity (DAS28 ≥3.2). Key findings indicate that swollen joint counts (OR=1.65, 95% CI [1.39, 2.04], p<.001), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores (OR=1.40, 95% CI [1.09, 1.81], p=.009), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) levels (OR=1.05, 95% CI [1.04, 1.06], p<.001), and positive anti-CCP antibody titers (OR=1.49, 95% CI [1.08, 2.05], p=.016) were significant predictors of higher disease activity in multivariable analysis. Patients with joint deformities had markedly increased odds of higher disease activity (OR=4.15, 95% CI [1.77, 10.43], p=.001). Conversely, body mass index (BMI), rheumatoid factor (RF) positivity, gender, and disease duration showed no significant associations with higher DAS28 scores in multivariable analysis. These results underscore the importance of swollen joint counts, functional disability, inflammatory markers, and autoantibody status in predicting disease severity in RA, highlighting the need for comprehensive assessment and targeted interventions for patients with elevated DAS28 scores.

The logistic regression analysis explored the association between comorbid conditions and disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis (RA), categorized using the DAS28 cutoff of <3.2 (low activity) and ≥3.2 (moderate-to-high activity). None of the comorbid conditions examined, including asthma (OR=0.89, 95% CI [0.55, 1.42], p=.632), coronary artery disease (CAD) (OR=0.83, 95% CI [0.35, 1.86], p=.658), diabetes mellitus (DM) (OR=1.19, 95% CI [0.81, 1.75], p=.374), hyperlipidemia (OR=0.83, 95% CI [0.50, 1.34], p=.445), hypertension (OR=1.20, 95% CI [0.81, 1.77], p=.370), osteoarthritis (OA) (OR=1.63, 95% CI [0.97, 2.75], p=.065), osteoporosis (OR=0.92, 95% CI [0.51, 1.62], p=.771), peptic ulcer disease (PUD) (OR=1.24, 95% CI [0.30, 4.81], p=.752), or thyroid conditions (OR=0.88, 95% CI [0.55, 1.38], p=.578), were significantly associated with higher disease activity in multivariable models. Although osteoarthritis showed a trend toward significance (p=.065), it did not meet the threshold for statistical significance. These findings suggest that the presence of these comorbidities does not independently contribute to predicting disease activity levels in RA as measured by DAS28 scores, emphasizing the need to consider other clinical and laboratory markers when evaluating disease severity.

Discussion

Anemia is a common hematological complication of RA. One study found that the lifetime prevalence of mild RA-associated anemia was 57%, with a cross-sectional prevalence of 31.5% after a mean disease duration of 10 years [24]. RA-associated anemia progressively worsens with disease duration if left untreated [25,26]. The relationship between low Hb levels and more aggressive RA disease activity has been established, although studies involving the MENA region remain scarce [14,25,27]. In our study, based on data from the KRRD registry, WHO-defined anemia was found in 48.45% of patients with RA. This result falls within the range of RA-associated anemia reported in other regional studies. The highest percentage of RA-associated anemia was reported to be 61% in a Saudi study, although the patient sample size was small and therefore may not be representative of the true prevalence [12]. The most common type of anemia in the KRRD could not be determined because MCH, MCV, MCHC, serum vitamin B12 levels, ferritin and iron levels were beyond the scope of the registry. Iron deficiency anemia was previously reported in patients with RA in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia [12]. However, anemia of chronic disease (ACD) is far more prevalent in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as RA, suggesting that the anemia observed in our patients is probably the result of ACD [12,13]. Our study found that in the RA anemic group, the mean Hb level was 7.7 g/dL in both male and female patients. This low Hb value is consistent with the WHO definition of severe anemia [23].

Anemia is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in various diseases and medical conditions [28]. In patients with normal kidney function, anemia was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization and death, after adjusting for age, gender, diabetes mellitus, and comorbidities. In patients with congestive heart failure, anemia correlates with significantly impaired cardiac functional capacity and increased mortality. Similarly, ACD is associated with an increased risk of morbidity and mortality [29,30]. In patients with RA, anemia is associated with high levels of disease activity and erosive arthritis, as well as an increased risk of mortality [1,18,25,31]. These adverse outcomes underscore the importance of diagnosing, treating and monitoring anemia in the comprehensive care of patients with RA.

Our study showed a significant association between low Hb levels and higher levels of disease activity in the DAS28 and CDAI scoring systems, but not in the SDAI, suggesting an inverse relationship between low Hb levels and increased auto-inflammatory processes observed in RA. The acute phase reactants ESR and CRP were also elevated in the anemic group, providing additional evidence of increased RA disease activity compared with the non-anemic group. In addition, our study found a small but statistically significantly worse HAQ score in the anemic group, reflecting the increased RA-associated disability in this cohort. RA-associated anemia is a common hematological complication that is mainly an immune-driven disorder involving a complex interplay of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6, widespread erythropoietic system dysfunction, and impaired iron homeostasis [32,33]. Previous studies similar to ours have confirmed the association between RA-associated anemia and disease activity. The CORRONA study showed a greater degree of RA disease severity in the low versus normal Hb patient groups, and the percentage of patients with low Hb in AR functional classes 3 and 4 was doubled [34]. Furthermore, ESR and CRP levels were approximately twice as high in the anemic group as in the normal Hb group. Another study found a significant association between lower Hb concentrations and higher DAS28 scores [25].

In our study, both the univariate and multivariate analyses of anemic RA patients with a DAS ≥3.2 showed that certain RA disease measures, such as disease severity (including joint swelling and associated deformities), HAQ scores, and anti-CCP titers, were predictive of low hemoglobin (Hb) levels. Univariate analysis also demonstrated that positive rheumatoid factor (RF) titers were significantly associated with low Hb levels; however, this association lost significance in multivariate analysis, suggesting that RF may act as a surrogate marker for inflammation rather than being an independent predictor of anemia. This may reflect collinearity with other variables, such as CRP, joint damage, or anti-CCP titers, which tend to track with RF positivity in seropositive RA.

Several mechanisms may underlie these associations. Chronic systemic inflammation is central to anemia in RA, primarily through pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α, which impair iron metabolism and suppress erythropoietin production and responsiveness. IL-6 stimulates hepatic production of hepcidin, a key regulator of iron homeostasis, which restricts iron availability for erythropoiesis, resulting in anemia of chronic disease despite normal or increased iron stores [13,35,36]. This process may be more active in patients with higher disease severity, as reflected by greater joint damage, disability (HAQ), and seropositivity (anti-CCP), explaining their independent association with lower Hb levels. The loss of significance for RF in multivariate models may also reflect its overlapping role with these other variables that more directly capture disease activity or severity.

This observation aligns with findings from other studies, such as a recent cohort from Oman, in which RA severity and elevated ESR were associated with low Hb levels, while variables such as HAQ scores and joint damage were not included in the final multivariate model [15]. Differences in sample size, study design, population characteristics, and variable selection may account for such discrepancies across studies. Additionally, demographic and geographic variabilities such as differences in genetic background, healthcare access, and comorbidity burden—can influence both disease phenotype and anemia prevalence, which may partly explain the differing predictive strengths of certain variables in various RA populations [37].

Our study also evaluated the potential role of comorbidities in anemia but found no statistically significant association between low Hb levels and chronic conditions such as asthma, ischemic heart disease, diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, peptic ulcer disease, or thyroid disorders. These findings reinforce the notion that the anemia observed in our cohort was predominantly RA-related rather than arising from external comorbidities. Notably, although the association between rheumatoid arthritis and coronary artery disease (CAD) is well documented in the literature, our data did not demonstrate a significant difference in ischemic heart disease prevalence between anemic and non-anemic RA patients (3.1% vs 3.0%, p=0.817) [38]. This discrepancy may be due to underreporting of CAD in the registry, a relatively low prevalence in our study population, or regional and demographic factors unique to our cohort. It is also possible that the prevalence or severity of these comorbidities was insufficient to impact hemoglobin levels significantly, or that their effects were diluted in a multivariate model focused on RA-specific variables. Moreover, the anemia in RA is increasingly understood as inflammation-driven, involving IL-6–mediated hepcidin upregulation and iron sequestration [35,36].

The lack of correlation between non-RA comorbidities and anemia strengthens the rationale for focusing on RA-driven mechanisms when evaluating and managing anemia in clinical practice. Furthermore, anemia in RA has been independently associated with increased fatigue, poorer functional status, and reduced quality of life, making it a clinically relevant outcome [39]. Emerging evidence also suggests that improvements in hemoglobin levels are associated with better RA disease outcomes, including reductions in joint swelling, alleviation of fatigue, and enhancements in patient-reported energy levels and quality-of-life measures. Collectively, these findings underscore the importance of systematically incorporating anemia screening and management into the routine care of patients with moderate to severe RA, particularly those exhibiting high disease activity or seropositivity [40].

Finally, this study provides important insights from a Middle Eastern population, a region that remains underrepresented in RA-related anemia research. Cultural, genetic, and healthcare system differences may affect disease presentation, treatment accessibility, and anemia prevalence. As such, our data contributes to closing the regional knowledge gap and may support the development of population-specific treatment approaches.

This study benefits from a large and diverse sample of 1,775 patients, enhancing the statistical power and generalizability of the findings within the MENA region. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the Kuwait Registry for Rheumatic Diseases (KRRD) relies heavily on retrospective data from patient medical records, which introduces the potential for recall bias—particularly for variables such as marital status, occupation, weight, and BMI. These variables, which may influence both RA disease activity and anemia, were not consistently recorded and therefore could not be analyzed. Second, while the registry emphasized objective clinical and laboratory assessments, symptom reporting was not systematically captured, limiting our ability to evaluate the frequency or progression of symptoms over the 10-year study period. Third, medication data—particularly on disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), corticosteroids, and NSAIDs—were inconsistently updated beyond baseline, preventing us from assessing the impact of treatment regimens on disease outcomes. Finally, key hematological parameters essential for a detailed evaluation of anemia—including MCV, MCH, MCHC, vitamin B12, ferritin, and serum iron—were not available in the registry dataset. This restricted our ability to distinguish between different types and causes of anemia. These limitations underscore the need for future prospective studies with more comprehensive and systematically collected clinical, laboratory, and treatment data.

Conclusion

Despite these limitations, our study showed a high prevalence of anemia in patients with RA in Kuwait. Our findings also suggest an inverse relationship between hemoglobin levels and RA disease activity based on high disease activity scores and HAQ scores. Studies have shown better RA disease outcomes with improved Hb levels, including reduced associated symptoms, such as joint swelling, improvement in reported energy levels, and quality of life measures. Despite its importance, anemia is not included in any RA disease activity scoring system. We conclude that the relationship between anemia and RA disease activity remains a topic that requires further research. Given the potential effect of disease-associated morbidity and mortality, physicians should be vigilant in monitoring Hb levels, as well as diagnosing and treating anemia in patients with RA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and in adherence to the highest ethical standards in medical research. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committees of the College of Medicine, University of Kuwait, the Kuwait Ministry of Health, and the Kuwait Institute for Medical Specializations (KIMS) (approval reference number: 2016/477). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the registry. All data were collected, analyzed, and reported with integrity and transparency, ensuring strict confidentiality and protection of participants’ privacy. The research complied with internationally accepted standards for research practice and reporting.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Kuwait Ministry of Health but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the Ethics Committee of Kuwait Ministry of Health.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Authors’ contributions

F. Ali was responsible for manuscript writing, reviewing, and overall manuscript preparation. F. Alsayegh contributed to the study conception and design, as well as manuscript review and editing. A. Alsaber performed the data analysis and prepared the tables and figures. A. Alherz was responsible for data collection and contributed to manuscript review and editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgments to declare.

Financial interests

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest or non-financial interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

References

2. Almoallim H, Al Saleh J, Badsha H, Ahmed HM, Habjoka S, Menassa JA, et al. A Review of the Prevalence and Unmet Needs in the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Africa and the Middle East. Rheumatol Ther. 2021 Mar;8(1):1–16.

3. Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Hoy D, Smith E, Bettampadi D, Mansournia MA, et al. Global, regional and national burden of rheumatoid arthritis 1990-2017: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study 2017. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019 Nov;78(11):1463–71.

4. Dore RK, Antonova JN, Burudpakdee C, Chang L, Gorritz M, Genovese MC. The Incidence, Prevalence, and Associated Costs of Anemia, Malignancy, Venous Thromboembolism, Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events, and Infections in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients by Treatment History in the United States. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022 Jun;4(6):473–82.

5. Løppenthin K, Esbensen BA, Østergaard M, Ibsen R, Kjellberg J, Jennum P. Morbidity and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis compared with an age- and sex-matched control population: A nationwide register study. J Comorb. 2019 Jun 3;9:2235042X19853484.

6. Hresko A, Lin TC, Solomon DH. Medical Care Costs Associated With Rheumatoid Arthritis in the US: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-Analysis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018 Oct;70(10):1431–8.

7. Mousavi SE, Nejadghaderi SA, Khabbazi A, Alizadeh M, Sullman MJM, Kaufman JS, et al. The burden of rheumatoid arthritis in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990-2019. Sci Rep. 2022 Nov 11;12(1):19297.

8. Song J, Zhang Y, Li A, Peng J, Zhou C, Cheng X, et al. Prevalence of anemia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and its association with dietary inflammatory index: A population-based study from NHANES 1999 to 2018. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 Jun 21;103(25):e38471.

9. Nikolaisen C, Figenschau Y, Nossent JC. Anemia in early rheumatoid arthritis is associated with interleukin 6-mediated bone marrow suppression, but has no effect on disease course or mortality. J Rheumatol. 2008 Mar;35(3):380–6. Epub 2008 Feb 1.

10. Khalaf W, Al-Rubaie HA, Shihab S. Studying anemia of chronic disease and iron deficiency in patients with rheumatoid arthritis by iron status and circulating hepcidin. Hematol Rep. 2019 Mar 12;11(1):7708.

11. Alanazi F. Clinical Profile and Comorbidities Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients in Sudair, Saudi Arabia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021 Nov;13(Suppl 2):S1583–7.

12. Al-Ghamdi A, Attar SM. Extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis: a hospital-based study. Ann Saudi Med. 2009 May-Jun;29(3):189–93.

13. Genedy MM, Shabana AA, Elghzaly AA, Bassiouni SA. Assessment of hepcidin in Egyptian patients with rheumatoid arthritis and its relation to anemia: a single-center study. Egyptian Rheumatology and Rehabilitation. 2024 Sep 10;51(1):44.

14. Chen YF, Xu SQ, Xu YC, Li WJ, Chen KM, Cai J, et al. Inflammatory anemia may be an indicator for predicting disease activity and structural damage in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Jun;39(6):1737–45.

15. Al-Mazedi MS, Rajan R, Al-Herz A, Alsaber A, Al-Jarallah M, Dashti R, et al. Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Stratified by Hemoglobin Levels: A Multi-center Study. Oman Med J. 2024 Sep 30;39(5):e671.

16. McWilliams DF, Kiely PDW, Young A, Joharatnam N, Wilson D, Walsh DA. Interpretation of DAS28 and its components in the assessment of inflammatory and non-inflammatory aspects of rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol. 2018 Mar 23;2:8.

17. Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, Kalden JR, Emery P, Eberl G, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003 Feb;42(2):244–57.

18. Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May;64(5):640–7.

19. Yetişir A, Sariyildiz A, Türk İ, Coskun Benlidayi I. Evaluation of inflammatory biomarkers and the ratio of hemoglobin-red cell distribution width in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors. Clin Rheumatol. 2024 Jun;43(6):1815–21.

20. Liu S, Liu J, Cheng X, Fang D, Chen X, Ding X, et al. Application Value of Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratio as a Novel Indicator in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Review Based on Clinical Evidence. J Inflamm Res. 2024 Oct 23;17:7607–17.

21. Kay J, Upchurch KS. ACR/EULAR 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012 Dec;51 Suppl 6:vi5–9.

22. Al-Herz A, Al-Awadhi A, Saleh K, Al-Kandari W, Hasan E, et al. A comparison of rheumatoid arthritis patients in Kuwait with other populations: results from the KRRD registry. Br J Med Med Res. 2016;14(9):1–11.

23. World Health Organization. Haemoglobin concentrations for the diagnosis of anaemia and assessment of severity. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

24. Wolfe F, Michaud K. Anemia and renal function in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006 Aug;33(8):1516–22.

25. Möller B, Scherer A, Förger F, Villiger PM, Finckh A; Swiss Clinical Quality Management Program for Rheumatic Diseases. Anaemia may add information to standardised disease activity assessment to predict radiographic damage in rheumatoid arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014 Apr;73(4):691–6.

26. Shah J, Farooq A, Zadran S, Kakar ZH, Zarrar M, Bhatti HMHS. Prevalence of Anemia in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Presenting at Multi-organization Tertiary Care Hospitals. Cureus. 2024 Oct 26;16(10):e72418.

27. Talukdar M, Barui G, Adhikari A, Karmakar R, Ghosh UC, Das TK. A Study on Association between Common Haematological Parameters and Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017 Jan;11(1):EC01–4.

28. Culleton BF, Manns BJ, Zhang J, Tonelli M, Klarenbach S, Hemmelgarn BR. Impact of anemia on hospitalization and mortality in older adults. Blood. 2006 May 15;107(10):3841–6.

29. Ugarph-Morawski A, Wändell P, Benson L, Savarese G, Lund LH, Dahlström U, et al. The association between anemia, hospitalization, and all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure managed in primary care: An analysis of the Swedish heart failure registry. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2025 Feb;129:105645.

30. Gafter-Gvili A, Schechter A, Rozen-Zvi B. Iron deficiency anemia in chronic kidney disease. Acta haematologica. 2019 May 15;142(1):44–50.

31. van Steenbergen HW, van Nies JA, van der Helm-van Mil AH. Anaemia to predict radiographic progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jul;72(7):e16.

32. Favalli EG. Understanding the Role of Interleukin-6 (IL-6) in the Joint and Beyond: A Comprehensive Review of IL-6 Inhibition for the Management of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2020 Sep;7(3):473–516.

33. Patil DS. Investigating the role of iron homeostasis in anemia of chronic disease: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Journal of Population Therapeutics and Clinical. 2025 Apr 22;726–34.

34. Furst DE, Chang H, Greenberg JD, Ranganath VK, Reed G, Ozturk ZE, et al. Prevalence of low hemoglobin levels and associations with other disease parameters in rheumatoid arthritis patients: evidence from the CORRONA registry. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2009 Jul-Aug;27(4):560–6.

35. Wei ST, Sun YH, Zong SH, Xiang YB. Serum Levels of IL-6 and TNF-α May Correlate with Activity and Severity of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Med Sci Monit. 2015 Dec 24;21:4030–8.

36. Wang CY, Babitt JL. Hepcidin regulation in the anemia of inflammation. Curr Opin Hematol. 2016 May;23(3):189-97.

37. Zhang M, Li M, Hu H, Li X, Tian M. Global, regional, and national burdens of rheumatoid arthritis in young adults from 1990 to 2019. Arch Med Sci. 2024 Feb 22;20(4):1153–62.

38. Bedeković D, Bošnjak I, Bilić-Ćurčić I, Kirner D, Šarić S, Novak S. Risk for cardiovascular disease development in rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024 Jun 4;24(1):291.

39. Torlinska B, Raza K, Filer A, Jutley G, Sahbudin I, Singh R, et al. Predictors of quality of life, functional status, depression and fatigue in early arthritis: comparison between clinically suspect arthralgia, unclassified arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024 Apr 20;25(1):307.

40. Tonino RPB, Zwaginga LM, Schipperus MR, Zwaginga JJ. Hemoglobin modulation affects physiology and patient reported outcomes in anemic and non-anemic subjects: An umbrella review. Front Physiol. 2023 Feb 15;14:1086839.