Abstract

Evolutionary path of cancer therapeutics which started around eighty-two years ago, following serendipitous discovery of nitrogen mustard [1] has been guided by an accelerated pace of new discoveries, an ever-increasing depth of understanding of intracellular biological processes [2] and application of advances made in other fields of science [3].

Success in any field, especially in cancer medicine, is based on embracing evolution in understanding other scientific fields [4] and its application to the forward move in cancer therapeutics. As such, we have gone through discovery of a diverse group of therapeutics, targeting different sub compartments of growth and proliferation pathways [5] and taking advantage of their synergistic efficacy, in different combinations [6]. Dissection of immune regulatory pathways [7] and their interaction with cancer cell has led to the generation of modern immune therapeutic agents. Single-cell sequencing technology [8] has paved the way for the development of spatial omics [9], which has opened the way on deeper understanding of tumor evolutionary path [10]. This would give us the opportunity to design a new generation of cancer therapeutics [11] intercepting with the forward evolutionary path of tumor mass.

Along this path, we face insurmountable barriers in developing meaningful and game changing treatment strategies by directing single changes in a hyper complex biological system [12], manifested by complexities of genome [13], epigenome [14], microRNA network [15], gene regulatory mechanisms [16], and protein-protein interactions [17]. Consequently, we need to search for a solution that enables us to freeze or slow down the forward evolutionary path of tumor mass [18], by making a single change in a game changing variable of cancer cell.

Spatial Entropyomics and Artificial Intelligence (AI), as the Next Wave

In contradistinction to the published spatial omics, including spatial genomics [19], epigenomics [20], transcriptomics [21], and proteomics [22], which present a hyper complex set of data in each category, spatial entropyomics [23], presents only one value, number or digit that applies to one single step in evolution of tumor mass.

Available mathematical models [24] defining master regulator complex network entropy of malignant cells prove and provide a much higher value for malignant cells, as compared with their normal counterparts. Forward evolutionary move of tumor mass [25] along the thermodynamic arrow of time [26], necessitates an ever-increasing master regulator complex network entropy of driver zone [27]. This could be calculated by employing single-cell technology [28]. The artificial intelligence (AI) revolution [29], which has already permeated various disciplines within biology and medicine, will enable us to calculate both the current and future master regulator complex network entropy of tumor mass driver zones.

As such, we could generate an archive of a series of numbers [digits] which belong to different driver zones [30] at different time brackets along the thermodynamic arrow of time from past to future. This is akin to digital revolution [31] which has replaced analog system in electronics.

Conversion of Master Regulator Complex Network Entropy: The Final Stride

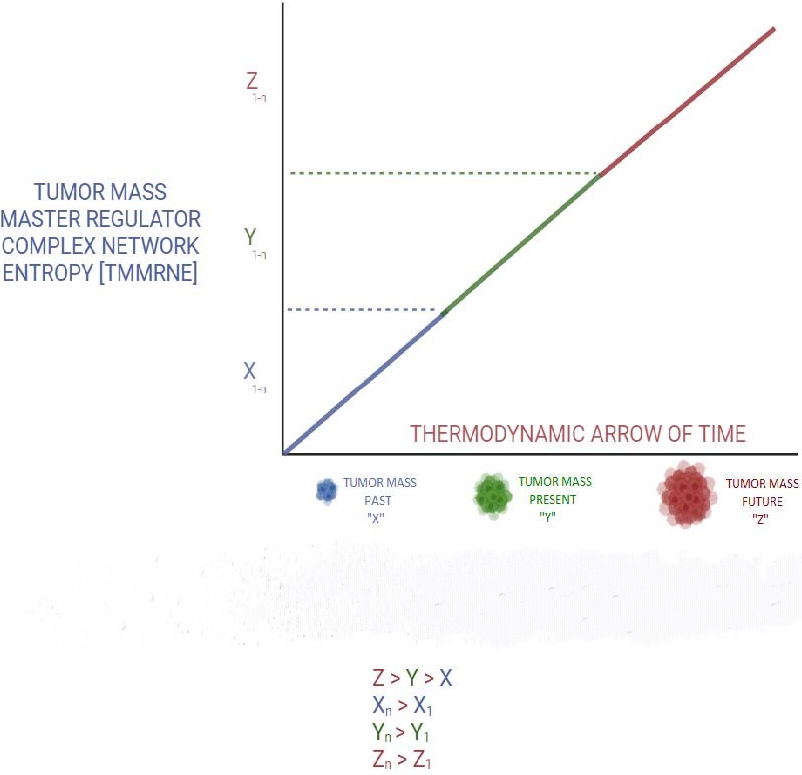

Major advances in nanotechnology [32], especially nano-delivery [33] and biological nanomachines [34] are expected to propel this venture to completion. Master regulator complex network entropy values of different malignant cells comprising the tumor mass [35] could get coded by a time value, as it relates to past, present, and future of tumor mass [36]. These numbers can be input into a specifically designed software program. This represents spatial entropyomics (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tumor mass MRNE along the thermodynamic arrow of time.

As tumor mass evolutionary path takes it from past to present and future, master regulator complex network entropy increases accordingly and to higher values.

Modifications in these values, needed to convert current and future driver zones [37] to past and present driver zones respectively, would be calculated by employing AI. This data is handed to nano-technology and nano-delivery team, whose task is to design a physical or biological modification [38] needed and its delivery to driver zones of interest, so that the driver zones would be shifted back in time [39]. As such, we would reverse the thermodynamic arrow of time [40] in tumor mass, ie: we would drag tumor mass back in time (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Dragging tumor mass back in time.

Taking master regulator network entropy of tumor mass back in time, i.e. changing MRNE [master regulator network entropy].

Value of Present to past and future to present.

By applying single cell sequencing technology and calculating MRNE of isolated cells, we could map tumor mass evolutinory path by those values. By using AI, we could predict the future drive zone MRNE. By employing nano-technology and nano-delivery through nanomachines, we could modify those values in reverse direction of themodynamic arrow of time.

On one occasion we might come in need of delivery of certain electrostatic force [41] to driver zone of interest and on another occasion we might come in need of delivery of a gene editing mechanism [42] using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-Cas9 to the zone of interest.

The common denominator among all different tasks is to take the driver zone to the past. This would freeze or significantly slow down the forward evolutionary speed of tumor mass [43] and would make cancer a chronic disease.

Conclusion

The history of cancer therapeutics which started eighty-two years ago, through serendipitous discovery of nitrogen mustard, has taken us through a tortuous path. Deep understanding of dynamics of tumor mass and its evolution has brought us to spatial entropyomics and digital age in modern oncology. Revolutions in AI, single-cell sequencing, nanotechnology and their application in the design of future cancer therapeutics, are expected to turn cancer into a chronic disease, even if not cured, without the toxicities associated with chemotherapy [44], radiation therapy [45], immunotherapy [46] and biological agents [47]. If we could make this historical achievement within one hundred years following introduction of nitrogen mustard into cancer therapeutics, our future generations would one day say, it took their ancestors one hundred years to solve one of the most complicated problems human race ever faced.

References

2. Montalbán-López M, Scott TA, Ramesh S, Rahman IR, van Heel AJ, Viel JH, et al. New developments in RiPP discovery, enzymology and engineering. Nat Prod Rep. 2021 Jan 1; 38(1):130-239.

3. Jiang P, Sinha S, Algae K, Hannenhalli S, Sahinalp C, Ruppin E. Big data in basic and translational cancer research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022 Nov; 22(11):625-39.

4. Gurevitch J, Koricheva J, Nakagawa S, Stewart G. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature. 2018 Mar 7;555(7695):175-82.

5. Huang R, Zhou PK. DNA damage repair: historical perspectives, mechanistic pathways and clinical translation for targeted cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Jul 9; 6(1):254.

6. Yu H, Ning N, Meng X, Chittasupho C, Jiang L, Zhao Y. Sequential Drug Delivery in Targeted Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2022 Mar 5; 14(3):573.

7. Cao LL, Kagan JC. Targeting innate immune pathways for cancer immunotherapy. Immunity. 2023 Oct 10; 56(10):2206-17.

8. Jovic D, Liang X, Zeng H, Lin L, Xu F, Luo Y. Single-cell RNA sequencing technologies and applications: A brief overview. Clin Transl Med. 2022 Mar; 12(3):e694.

9. Saviano A, Henderson NC, Baumert TF. Single-cell genomics and spatial transcriptomics: Discovery of novel cell states and cellular interactions in liver physiology and disease biology. J Hepatol. 2020 Nov; 73(5):1219-30.

10. Bolouri H. Network dynamics in the tumor microenvironment. Semin Cancer Biol. 2015 Feb;30:52-9.

11. Grodzinski P, Kircher M, Goldberg M, Gabizon A. Integrating Nanotechnology into Cancer Care. ACS Nano. 2019 Jul 23; 13(7):7370-76.

12. Cheng F, Liu C, Shen B, Zhao Z. Investigating cellular network heterogeneity and modularity in cancer: a network entropy and unbalanced motif approach. BMC Syst Biol. 2016 Aug 26; 10 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):65.

13. Del Giacco L, Cattaneo C. Introduction to genomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2012; 823:79-88.

14. Ganesan A. Epigenetics: the first 25 centuries. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018 Jun 5;373(1748):20170067.

15. Liu Q, Zhang W, Wu Z, Liu H, Hu H, Shi H, Li S, Zhang X. Construction of a circular RNA-microRNA-messengerRNA regulatory network in stomach adenocarcinoma. J Cell Biochem. 2020 Feb;121(2):1317-31.

16. Davidson EH, Levine MS. Properties of developmental gene regulatory networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008 Dec 23;105(51):20063-6.

17. Wang T, Yang N, Liang C, Xu H, An Y, Xiao S, et al. Detecting Protein-Protein Interaction Based on Protein Fragment Complementation Assay. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2020; 21(6):598-610.

18. Leong SP, Witz IP, Sagi-Assif O, Izraely S, Sleeman J, Piening B, et al. Cancer microenvironment and genomics: evolution in process. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022 Feb; 39(1):85-99.

19. Dhainaut M, Rose SA, Akturk G, Wroblewska A, Nielsen SR, Park ES, et al. Spatial CRISPR genomics identifies regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2022 Mar 31;185(7):1223-39.e20.

20. Arslan E, Schulz J, Rai K. Machine Learning in Epigenomics: Insights into Cancer Biology and Medicine. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 2021 Dec;1876(2):188588.

21. Robles-Remacho A, Sanchez-Martin RM, Diaz-Mochon JJ. Spatial Transcriptomics: Emerging Technologies in Tissue Gene Expression Profiling. Anal Chem. 2023 Oct 24;95(42):15450-60.

22. Aslam B, Basit M, Nisar MA, Khurshid M, Rasool MH. Proteomics: Technologies and Their Applications. J Chromatogr Sci. 2017 Feb;55(2):182-96.

23. Afrasiabi K. Spatial entropyomics: The path to future cancer therapeutics. Journal of Cancer. 2022;3(2):50-4.

24. Rich JN. Cancer stem cells: understanding tumor hierarchy and heterogeneity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Sep;95(1 Suppl 1):S2-S7.

25. Graham TA, Sottoriva A. Measuring cancer evolution from the genome. J Pathol. 2017 Jan;241(2):183-91.

26. Ben-Naim A. Entropy and Time. Entropy (Basel). 2020 Apr 10;22(4):430.

27. Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu J, et al. Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer research: progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2021 Jun 9;14(1):91.

28. Liang SB, Fu LW. Application of single-cell technology in cancer research. Biotechnol Adv. 2017 Jul;35(4):443-9.

29. Weidlich V, Weidlich GA. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine and Radiation Oncology. Cureus. 2018 Apr 13;10(4):e2475.

30. Luchini C, Pea A, Scarpa A. Artificial intelligence in oncology: current applications and future perspectives. Br J Cancer. 2022 Jan;126(1):4-9.

31. Shrestha B, Wang L, Brey EM, Uribe GR, Tang L. Smart Nanoparticles for Chemo-Based Combinational Therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2021 Jun 8;13(6):853.

32. Nedorezova DD, Fakhardo AF, Nemirich DV, Bryushkova EA, Kolpashchikov DM. Towards DNA Nanomachines for Cancer Treatment: Achieving Selective and Efficient Cleavage of Folded RNA. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2019 Mar 26;58(14):4654-8.

33. Chen YJ, Dalchau N, Srinivas N, Phillips A, Cardelli L, Soloveichik D, et al. Programmable chemical controllers made from DNA. Nat Nanotechnol. 2013 Oct;8(10):755-62.

34. Chaturvedi VK, Singh A, Singh VK, Singh MP. Cancer Nanotechnology: A New Revolution for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy. Curr Drug Metab. 2019;20(6):416-29.

35. Youssef N, Budd A, Bielawski JP. Introduction to Genome Biology and Diversity. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1910:3-31.

36. Ho D, Wang P, Kee T. Artificial intelligence in nanomedicine. Nanoscale Horiz. 2019 Mar 1;4(2):365-77.

37. Herrera-Ibatá DM. Machine Learning and Perturbation Theory Machine Learning (PTML) in Medicinal Chemistry, Biotechnology, and Nanotechnology. Curr Top Med Chem. 2021;21(7):649-60.

38. Fan D, Cao Y, Cao M, Wang Y, Cao Y, Gong T. Nanomedicine in cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Aug 7;8(1):293.

39. Sidow A, Spies N. Concepts in solid tumor evolution. Trends Genet. 2015 Apr;31(4):208-14.

40. Lucia U, Deisboeck TS, Ponzetto A, Grisolia G. A Thermodynamic Approach to the Metaboloepigenetics of Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Feb 7;24(4):3337.

41. Zhang XC, Li H. Interplay between the electrostatic membrane potential and conformational changes in membrane proteins. Protein Sci. 2019 Mar;28(3):502-12.

42. Savić N, Schwank G. Advances in therapeutic CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Transl Res. 2016 Feb;168:15-21.

43. Pucci C, Martinelli C, Ciofani G. Innovative approaches for cancer treatment: current perspectives and new challenges. Ecancermedicalscience. 2019;13:961.

44. Livshits Z, Rao RB, Smith SW. An approach to chemotherapy-associated toxicity. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014 Feb;32(1):167-203.

45. Baskar R, Lee KA, Yeo R, Yeoh KW. Cancer and radiation therapy: current advances and future directions. Int J Med Sci. 2012;9(3):193-9.

46. Zhang H, Chen J. Current status and future directions of cancer immunotherapy. J Cancer. 2018 Apr 19;9(10):1773-81.

47. Conte P, Guarneri V. The next generation of biologic agents: therapeutic role in relation to existing therapies in metastatic breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2012 Jun;12(3):157-66