Keywords

Irreversible electroporation, Tumor microenvironment, Toll-like receptor agonist, PD1 blockade, Cancer immunotherapy

Commentary

Over the years, several ablation techniques, such as radiofrequency ablation (RFA), microwave ablation, and cryoablation, have been developed and implemented in the treatment of different cancers [1]. Of these ablation technologies, RFA is the most widely used [2]. RFA is a form of thermal ablation that relies on radio waves to produce an electrical current at the tip of an inserted electrode, thus allowing for heat production at the site of the tumor [1]. Compared to conventional surgical resection, RFA is more cost efficient, less invasive, and equally effective in specific cases such as small liver metastases [1,2]. Nonetheless, the major drawbacks of RFA are the “heat sink” side effect damaging nearby nerves or blood vessels and incomplete tumor ablation leading to cancer recurrence [1,2]. More recently, irreversible electroporation (IRE) has been explored as a novel ablation strategy [3,4]. IRE is a non-thermal approach that utilizes short electrical pulses to irreversibly puncture the tumor cell membrane, leading to cell death [1,3]. Compared to RFA, IRE is particularly advantageous because it does not rely on heat and therefore preserves delicate structures including blood vessels, bile ducts, and lactiferous ducts [1,3]. While preliminary success has been demonstrated in the treatment of various cancers including liver, pancreas, breast, and lung, research is required to optimize IRE treatment efficacy [3,4]. One such strategy involves the combination of IRE with immunotherapeutic anticancer agents [5].

Several promising immunotherapies have emerged in the treatment of cancer. First, toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of pattern recognition receptors that recognize conserved pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and play a role in activating immune responses [6,7]. TLRs are known to stimulate antigen presenting cells (APCs) such as dendritic cells (DCs), that can subsequently activate a tumor-specific T cell response [6]. TLR agonists—such as TLR3 agonist poly I:C (pIC) and TLR9 agonist CpG—have been shown to enhance antitumor T cell responses [2,6]. Second, programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) is highly expressed in B cells, T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and myeloid cells [8]. Its ligand, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), is expressed in DCs, macrophages, T cells, NK cells, and tumor cells [8]. Importantly, the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 on CD8+ T cells triggers the inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, leading to T cell dysfunction and exhaustion [9]. Blocking this axis—either by anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 antibodies—is a popular method used in cancer immunotherapy [8]. Overall, several strategies exist to enhance antitumor immune response.

The immunotolerant tumor microenvironment (iTME) is a key obstacle in anticancer immunotherapy. In short, the iTME plays a central role in enhancing tumor progression and metastasis, and resistance to tumor immunotherapy [10,11]. Various cell types can be found within the iTME, including both immune and non-immune cells [10,11]. TME immune cells are often classified into two subgroups: 1) the immunogenic group and 2) the immunotolerant group. In the immunogenic group CD8+CD103+CD11c+ type-1 conventional dendritic cells (cDC1s) strongly stimulate CD8+ T cell responses, CD11b+F4/80+CD169+ macrophages (M169) trigger antitumor activity by preferentially phagocytosing apoptotic tumor cells and presenting tumor antigens to CD8+ T cells, and CD11b+F4/80+MHCII+ type-1 tumor-associated macrophages (M1) secrete inflammatory cytokines that drive polarization of immunogenic CD4+ Th1 cells [12]. In the immunotolerant group, CD11b+Gr1+Ly6G+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)—one of the key players in iTME—activate suppressive CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells and show potent inhibitory effect on CD8+ T cell responses, CD11b+F4/80+MHCII- type-2 macrophages (M2) secrete suppressive cytokines TGF-β and IL-10, and CD317+B220+ plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) strongly favor inhibitory Treg cell expansion [13]. Due to an imbalance between immunogenic and immunotolerant factors, the TME is highly immunosuppressive and promotes conditions that are conducive to tumor growth, development, and enhanced evasion of immunosurveillance [10]. Additionally, the characteristics of the TME have been shown to vary depending on tumor stage, with the TME becoming increasingly immunotolerant as the cancer progresses [10]. For these reasons, anticancer immunotherapeutic agents that work by stimulating host immune cells have limited efficacy when administered alone [10]. It follows that targeting the TME may be a viable strategy to increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy [10].

Recent studies have revealed that IRE ablation coupled with various immunotherapeutic strategies may increase cancer treatment efficacy [14]. First, Zhao and colleagues demonstrated that IRE in combination with PD-1 blockade significantly suppressed tumor growth and prolonged survival of mice bearing pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma or melanoma tumors [15]. Their IRE+PD-1 blockade regimen stimulated an increase in selective tumor infiltration by CD8+ T cells. Further, they found that IRE+PD-1 blockade was able to mildly modulate the TME by increasing the CD8+ T cell to Treg cell ratio. Importantly, they concluded that tumor infiltration by CD8+ T cells is the key to superior efficacy of IRE+PD-1 blockade treatment. Second, Narayana and colleagues determined that IRE combined with both TLR7 agonist 1V270 and PD-1 blockade improved treatment efficacy [16]. Researchers observed an increase in cDC1s in the TME resulting in the inhibition of primary pancreatic tumor growth. Notably, researchers found that IRE+TLR7 agonist+PD-1 blockade led to the regression of distant untreated tumors in mice. Third, Zhang and colleagues have demonstrated that OX40 agonist in combination with IRE triggers a systemic antitumor immune response [17]. OX40 is expressed in activated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Importantly, stimulation of OX40 signaling promotes the differentiation, proliferation, and survival of effector T cells as well as the generation of memory T cells [17]. Researchers discovered that co-administration of OX40 with IRE eradicated 80% of primary tumors in mice, led to an increase in CD8+ T cell tumor infiltration, and conferred immunity to tumor rechallenge. Lastly, Burbach and colleagues found that IRE combined with CTLA-4 immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) led to increased expansion of tumor-specific CD8+ T cells [18]. Researchers determined that IRE + CTLA-4 ICI established a robust memory T cell population that was associated with tumor remission and protection from tumor rechallenge [18]. Overall, recent research suggests that IRE in combination with immunotherapeutic strategies is a promising approach to cancer treatment.

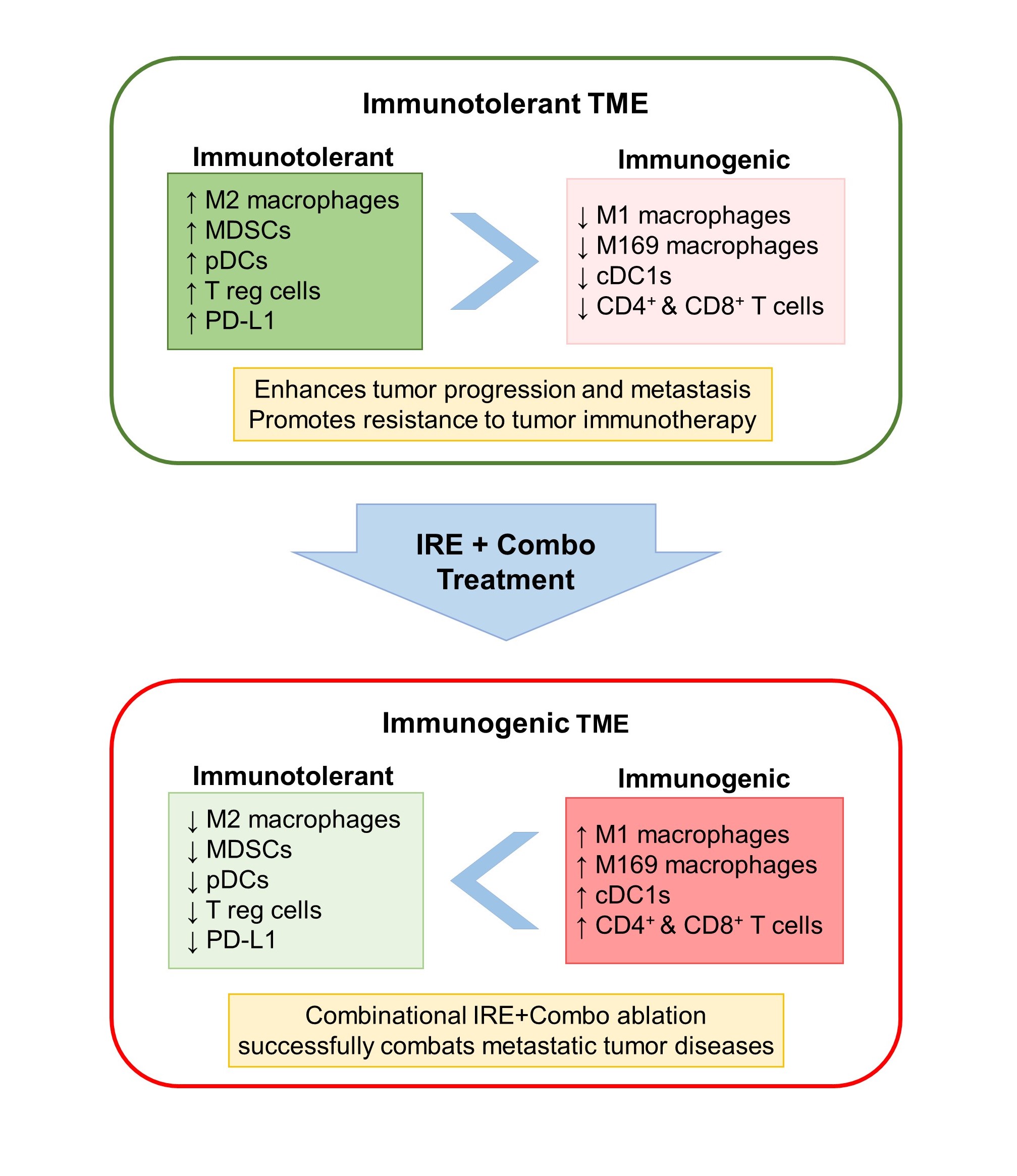

To improve the therapeutic efficacy of IRE ablation,we developed treatment protocols involving IRE in combination with either TLR3/9 agonists (pIC and CpG), PD-1 blockade, or both (IRE+Combo), and investigate their stimulatory effect on CD8+ T cell response and antitumor immunity in a mouse model bearing large primary and medium distant EG7 lymphomas engineered to express chicken ovalbumin (OVA) [19]. OVA was used as a nominal tumor antigen to detect tumor-specific CD8+ T cell response. First, we found that IRE induces massive EG7 tumor apoptosis in the central area of tumor tissue, but IRE or Combo alone was unable to stimulate significant OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response and inhibition of tumor growth [19]. However, IRE ablation combined with either pIC/CpG (IRE+pIC/CpG) or PD-1 blockade (IRE+PD-1 blockade) induced significant (3.8% or 1.79%) OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response, with IRE+pIC/CpG having more efficient inhibition of EG7 tumor growth than IRE+PD-1 blockade [19]. Importantly, IRE+Combo treatment induced potent OVA-specific CD8+ T cell response (5.8%), leading to eradication of both primary and untreated distant EG7 tumors or lung tumor metastasis [19]. To elucidate its underlying mechanism, we used flow cytometry to analyze immune cell profiles of enzymatically prepared tumor tissue single-cell suspensions stained with a cocktail of antibodies recognizing different cellular markers of various immune subsets. We demonstrated that, compared to IRE+PD-1 blockade, IRE+pIC/CpG plays a larger role in reducing the abundance of immunotolerant M2, MDSCs, pDCs and Treg cells, and in increasing the frequency of immunogenic cDC1, M1, M169, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [19]. In contrast, IRE+PD-1 blockade treatment demonstrates more efficient capacity in dramatically reducing inhibitory PD-L1 expression on suppressive M2, MDSCs and EG7 tumor cells than IRE+pIC/CpG. Therefore, we uncovered that TLR3/9 agonists and PD-1 blockade play distinct roles, whereby TLR3/9 agonists contribute mainly to modulating immune cell profiles and PD-1 blockade contributes mainly to downregulating PD-L1 expression in the TME. We also demonstrated that IRE+Combo induces cooperative modulational effects to convert iTMEs by reducing immunotolerant immune cell subsets and PD-L1 expression and increasing immunogenic subsets [19]. In addition to downregulation of PD-L1, IRE+Combo also greatly modulates M2, MDSCs and EG7 tumor cells in peripheral areas of tumor tissues [19]. IRE+Combo-treated M2, MDSCs and EG7 tumor cells show downregulation of suppressive IDO and arginase, compared to IRE-treated ones [19]. Given the evidence that IRE+Combo treatment of primary EG7 tumors induces the “abscopal” effect by eradicating untreated distant tumors, we wanted to investigate whether IRE+Combo treatment modulates the iTME in distant tumors. Interestingly, we found that the iTME in distant tumors is similarly converted, though in slightly milder content than that in treated primary tumors [19]. Lastly, we investigated whether IRE+Combo treatment affects systemic immune tolerance. Most notably, we showed that IRE+Combo promotes cDC1 and effector CD8+ T cell responses in tumor-draining lymph nodes, and reduces inhibitory M2, MDSCs, and cytokine TGF-β and increases immunogenic cytokines IL-2 and IFN-γ in mouse peripheral blood [19], indicating that IRE+Combo is able to convert not only the local iTMEs, but can also confer systemic immunotolerance. This regimen successfully eradicated primary and untreated distant tumors as well as lung tumor metastases. These findings demonstrate that combining IRE ablation to induce massive tumor apoptosis and release a large amount of tumor antigens with Combo adjuvants to convert iTME and systemic immune tolerance and activate CD8+ T cell responses and antitumor immunity is a promising strategy in cancer therapy (Figure 1) and warrants further investigation.

Figure 1. Effects of IRE+Combo treatment on the TME immune cell composition. Combinational IRE+Combo ablation effectively combats metastatic tumors by converting the immunotolerant TME. Specifically, IRE+Combo treatment downregulates inhibitory PD-L1, reduces the abundance of immunotolerant M2, MDSCs, pDCs, and T reg cells, and increases the number of immunogenic M1, M169, cDC1, CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in the TME.

In summation, the modulation of the iTME is an intriguing approach for cancer immunotherapy but remains poorly understood [20]. Our recent findings strengthen the idea that immunomodulatory strategies work synergistically with tumor ablation treatment to eradicate tumors by converting iTMEs [14-16,19,21]. Moving forward, research may continue to investigate IRE in combination with different immunomodulatory adjuvants and may also explore other avenues to transform the iTME. Targeting the TME is a promising strategy for cancer therapy and efforts should continue to be made to enhance our understanding. Overall, further research should be conducted to elucidate the most effective combination of tumor ablation and immunomodulatory adjuvants.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

2. Xu A, Zhang L, Yuan J, Babikr F, Freywald A, Chibbar R, et al. TLR9 agonist enhances radiofrequency ablation-induced CTL responses, leading to the potent inhibition of primary tumor growth and lung metastasis. Cell Mol Immunol. 2019 Oct;16(10):820-32.

3. Zhang X, Zhang X, Ding X, Wang Z, Fan Y, Chen G, et al. Novel irreversible electroporation ablation (Nano-knife) versus radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of solid liver tumors: a comparative, randomized, multicenter clinical study. Front Oncol. 2022 Sep 28;12:945123.

4. Zhang N, Li Z, Han X, Zhu Z, Li Z, Zhao Y, et al. Irreversible Electroporation: An Emerging Immunomodulatory Therapy on Solid Tumors. Front Immunol. 2022 Jan 7;12:811726.

5. Tian G, Guan J, Chu Y, Zhao Q, Jiang T. Immunomodulatory Effect of Irreversible Electroporation Alone and Its Cooperating With Immunotherapy in Pancreatic Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021 Sep 21;11:712042.

6. Kaczanowska S, Joseph AM, Davila E. TLR agonists: our best frenemy in cancer immunotherapy. J Leukoc Biol. 2013 Jun;93(6):847-63.

7. Kaur A, Baldwin J, Brar D, Salunke DB, Petrovsky N. Toll-like receptor (TLR) agonists as a driving force behind next-generation vaccine adjuvants and cancer therapeutics. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2022 Oct 1;70:102172.

8. Wang Q, Xie B, Liu S, Shi Y, Tao Y, Xiao X, et al. What Happens to the Immune Microenvironment After PD-1 Inhibitor Therapy? Front Immunol. 2021 Dec 23;12:773168.

9. Nelson CE, Mills LJ, McCurtain JL, Thompson EA, Seelig DM, Bhela S, et al. Reprogramming responsiveness to checkpoint blockade in dysfunctional CD8 T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Feb 12;116(7):2640-5.

10. Pitt JM, Marabelle A, Eggermont A, Soria JC, Kroemer G, Zitvogel L. Targeting the tumor microenvironment: removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 2016 Aug 1;27(8):1482-92.

11. Ngiow SF, Young A. Re-education of the Tumor Microenvironment With Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2020 Jul 28;11:1633.

12. Asano K, Nabeyama A, Miyake Y, Qiu CH, Kurita A, Tomura M, et al. CD169-Positive Macrophages Dominate Antitumor Immunity by Crosspresenting Dead Cell-Associated Antigens. Immunity. 2011 Jan 28;34(1):85-95.

13. Conrad C, Gregorio J, Wang YH, Ito T, Meller S, Hanabuchi S, et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Promote Immunosuppression in Ovarian Cancer via ICOS Costimulation of Foxp3+ T-Regulatory Cells. Cancer Res. 2012 Oct 14;72(20):5240-9.

14. van den Bijgaart RJE, Schuurmans F, Fütterer JJ, Verheij M, Cornelissen LAM, Adema GJ. Immune Modulation Plus Tumor Ablation: Adjuvants and Antibodies to Prime and Boost Anti-Tumor Immunity In Situ. Front Immunol. 2021 Apr 14;12:617365.

15. Zhao J, Wen X, Tian L, Li T, Xu C, Wen X, et al. Irreversible electroporation reverses resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in pancreatic cancer. Nat Commun. 2019 Feb 22;10(1):899.

16. Narayanan JS, Ray P, Hayashi T, Whisenant TC, Vicente D, Carson DA, et al. Irreversible Electroporation Combined with Checkpoint Blockade and TLR7 Stimulation Induces Anti-Tumor Immunity in a Murine Pancreatic Cancer Model. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019 Oct;7(10):1714-26.

17. Zhang QW, Guo XX, Zhou Y, Wang QB, Liu Q, Wu ZY, et al. OX40 agonist combined with irreversible electroporation synergistically eradicates established tumors and drives systemic antitumor immune response in a syngeneic pancreatic cancer model. Am J Cancer Res. 2021 Jun 15;11(6):2782-801.

18. Burbach BJ, O’Flanagan SD, Shao Q, Young KM, Slaughter JR, Rollins MR, et al. Irreversible electroporation augments checkpoint immunotherapy in prostate cancer and promotes tumor antigen-specific tissue-resident memory CD8+ T cells. Nat Commun. 2021 Jun 23;12:3862.

19. Babikr F, Wan J, Xu A, Wu Z, Ahmed S, Freywald A, et al. Distinct roles but cooperative effect of TLR3/9 agonists and PD-1 blockade in converting the immunotolerant microenvironment of irreversible electroporation-ablated tumors. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021 Dec;18(12):2632-47.

20. Tiwari A, Trivedi R, Lin SY. Tumor microenvironment: barrier or opportunity towards effective cancer therapy. J Biomed Sci. 2022 Oct 17;29:83.

21. Eresen A, Yang J, Scotti A, Cai K, Yaghmai V, Zhang Z. Combination of natural killer cell-based immunotherapy and irreversible electroporation for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Jul;9(13):1089.