Abstract

Brain tumors, especially malignant gliomas and metastases, continue to pose serious clinical challenges due to their complex biology and limited treatment options. The traditional research paradigm mainly focuses on the tumor cells themselves and their interaction with the immune microenvironment, while the critical role of the nervous system (including neurons, glial cells, neurotransmitters/modulators, and nerve fibers) in the pathological process of tumors has been underestimated for a long time. This review systematically reviews breakthrough research in recent years, revealing that the nervous system plays an indispensable driving role in the development, proliferation, invasion, and treatment resistance of brain tumors. Specifically, neuronal activity profoundly influences tumor behavior through the utilization of direct "neuron-tumor synapses", neurotransmitter signaling (e.g., glutamate, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), neuropeptides), and axon-guiding molecules. At the same time, glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, etc.) undergo phenotypic remodeling in the tumor microenvironment, and their secretion products and functional status have complex regulatory effects on tumor progression. Conversely, the growth of brain tumors also violently reshapes the structure and function of the nervous system (such as the destruction of nerve fiber bundles) and function (such as inducing epilepsy, cognitive impairment, and neurological deficits), which involves multiple mechanisms such as neuroplasticity changes, neuroinflammation, metabolic competition, and neurovascular unit destruction. This broad and profound two-way interaction between the nervous system and brain tumors not only provides a new perspective for understanding the unique pathophysiology of brain tumors but also highlights its important clinical translational value as potential diagnostic markers and therapeutic targets. Tumordating the neural regulatory network from neurons to the entire tumor microenvironment will lay the foundation for the development of innovative therapeutic strategies targeting the "neuro-tumor axis", which is expected to break through the current bottleneck in brain tumor treatment.

Keywords

Brain tumors, Nervous system, Tumor microenvironment, Neuron-tumor synapses, Neurotransmitters, Neuroglial cells, Targeted therapy

Introduction

A brain tumor is a space-occupying lesion that occurs because of abnormal cell growth in the cranial cavity (intracranial) [1–3]. They are mainly divided into two main categories: primary brain tumors originate in the brain tissue itself or its adjacent structures (such as meninges, pituitary gland, cranial nerves, blood vessels, etc.) [4,5]. Depending on the type of cell of origin and biological behavior (benign or malignant), it can be subdivided into various subtypes, among which gliomas (especially highly malignant glioblastomas) are the most common and aggressive primary malignancies; Other common types include meningiomas, pituitary adenomas, acoustic neuromas, and medulloblastoma [6].

Metastatic brain tumors (brain metastases) originate from malignant tumors in other parts of the body (such as lung cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, etc.) and cancer cells spread to the brain through the blood circulation or lymphatic system. The incidence of metastatic brain tumors is higher than that of most primary malignant brain tumors [7]. The growth of these tumors occupies a limited cranial space and causes a range of symptoms, including headaches, seizures, neurological deficits (such as motor, sensory, and language impairments), and cognitive decline, by compressing, infiltrating, or destroying the surrounding normal brain tissue, nerve fibers, and blood vessels. Its severity and treatment challenges are highly dependent on the type, location, growth rate and degree of malignancy of the tumor, especially the high-grade glioblastoma, which is still a difficult problem to overcome in the field of neurosurgery and oncology [8].

The nervous system is the most complex regulatory system in the human body, consisting of the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) and peripheral nervous system (nerves, ganglia, and receptors throughout the body), and its core functional units are neurons (responsible for the rapid transmission of electrochemical signals) and glial cells (multiple functions such as support, nutrition, insulation, and immune defense) [9]. The system is like the "command center" and "communication network" of the body, by receiving sensory information from the internal and external environment, it carries out highly integration, processing and decision-making in the center, and then sends instructions to precisely regulate somatic movements (such as muscle contraction), visceral activities (such as heartbeat, digestion) and endocrine functions through peripheral nerves, so as to maintain the stability of the body's internal environment (homeostasis) and respond to external changes adaptively [10]. In addition, the nervous system is also the biological basis of higher cognitive activities (e.g., learning, memory, thinking, emotion) and consciousness, and its plasticity (i.e., the ability to change structure and function based on experience) is a key mechanism for learning and injury repair [11].

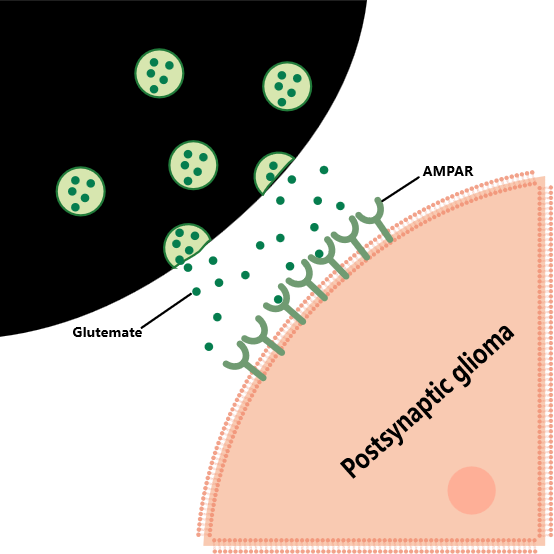

The role of the nervous system in pathophysiology is far beyond traditional understanding, especially in the regulation of tumor microenvironment. As an emerging interdisciplinary field, cancer neuroscience has revealed the precise mechanism of the nervous system's active involvement in tumor progression through cutting-edge technology in recent years. In 2021, Venkatesh et al. used single-cell sequencing and calcium imaging techniques to demonstrate that glioma cells sense glutamate released by neuronal activity through alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isooxazole-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors, triggering intracellular calcium oscillations to drive tumor proliferation [12]. In the same year, Mauffrey et al. discovered that there is a specific program for autonomic neogenesis in breast cancer tissues, and sympathetic nerve fibers activate tumor cell β2-adrenergic receptors by releasing norepinephrine, promoting angiogenesis and immune escape [13]. In 2023, Chen's team used optogenetics to manipulate mouse hippocampal neurons to demonstrate for the first time that γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic signaling can directly inhibit the differentiation of glioma stem cells, revealing the spatiotemporal-specific regulation of tumor stemness by neurotransmitters [14]. More critically, Jan Versijpt et al. concluded that sensory neurons remodel tumor-associated macrophage phenotypes by releasing calcitonin gene-related peptides (CGRPs) to establish a neuro-immune-tumor triple dialogue axis to accelerate pancreatic cancer metastasis [15]. These breakthrough studies not only validate the role of the nervous system as an active regulator of tumor progression, but also provide a molecular basis for the clinical translation of targeted nerve signaling pathways such as glutamate antagonists and β-blockers. Breakthroughs have been made in the regulation of neuronal activity on tumor progression. In 2023, the fusion application of single-cell spatial transcriptome and in vivo imaging technology revealed the systemic role of the nervous system in cancer: Venkataramani et al. found that after glioma cells receive glutamatergic synaptic input through the AMPA receptor, they release brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in reverse, activate neuronal tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB) receptors to form bidirectional excitatory circuits, and accelerate tumor invasion [16]. At the same time, Zhao's team confirmed that Substance P, released by sensory neurons in the breast cancer microenvironment, recruits immunosuppressive Treg cells through neurokinin-1 receptors (NK1R) to drive metastatic immune escape [17]. In 2024, the study was further extended to the systemic level: Chen et al. demonstrated that miR-21-5p carried by pancreatic cancer exosomes can penetrate the blood-brain barrier, target GABAergic neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus, and induce cachexia-related metabolic disorders [18]. These findings have prompted a paradigm shift towards multi-scale interaction networks, which was noted in the consensus published by the International Union for Cancer Neuroscience (ICNS) in 2023: 1) At the local level, astrocytes deliver cyclic guanosine monophosphate–adenosine monophosphate (cGAMP) molecules to tumors through gap junctions to activate the stimulator of interferon genes (STING pathway) and promote glioma radiotherapy resistance [19]. 2) At the systemic level, the vagus-spleen axis regulates bone marrow myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC) differentiation through acetylcholine, weakening the anti-PD-1 efficacy [20]. The current field has transcended the "cell-cell binary effect" and focused on the four-dimensional dynamic network of neuro-immune-metabolism-blood vessels, and its clinical translation is reflected in: Perampanel, an AMPA receptor antagonist targeting neuron-tumor synapses, combined with radiotherapy, can extend the survival of glioblastoma mice by 40%, while immunotherapy-elicited anti-GABAβ receptor autoantibodies were identified as key mediators of neurocognitive disorders [21–25]. Neuronal activity directly drives tumor progression through electrochemical signals, and the mechanism of this has been revealed in recent years. The 2023 Nature study confirmed that glioma cells receive neuronal signals by forming bidirectional AMPA receptor-dependent glutamatergic synapses, and at the same time reverse release (BDNF) to activate neuronal TrkB receptors to form a "tumor-neural positive feedback loop", which increases tumor infiltration in mouse models by 2.1 times [26–30]. What's even more subversive is that in 2025, Nature found that pancreatic cancer cells "gene brainwash" sensory neurons by secreting molecules such as Slit2/Lin28b, inducing a 230% surge in sympathetic tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression, while inhibiting pain-related CGRP neuronal function, and constructing a "pancreatic cancer neuro signature" (PCN) that promotes angiogenesis and immune evasion, even after tumor resection. At the metabolic level, the 2024 Science study revealed that breast cancer cells directly steal neuronal mitochondria through tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), which increases the oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) ability of cancer cells by 3 times, and enhances the colonization ability of metastases—46% of cancer cells in brain metastases carry neuronal mitochondria, which is significantly higher than 1.6% of primary lesions (P=1.2275×10??) [31–33]. This process is regulated by podoplanin (PDPN) cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) through exosome delivery of non-coding RNA PIAT fragments, inducing YBX1-dependent m5C modification to promote neural invasion [34,35]. The bidirectional regulation of neurotransmitters has also been redefined: in addition to glutamate, Cell found in 2023 that GABAergic signaling plays an inhibitory role in glioma stem cell differentiation, while substance P recruits regulatory T cells (Treg) through the NK1R to drive lung metastasis of breast cancer. In addition, in 2025, Nature confirmed that there is electrical synaptic coupling between neurons and cancer cells, and glioblastoma cells express the voltage-gated sodium channel Nav1.3, which increases the sensitivity to brain waves by 60%, and blocking this channel can reduce tumor aggressiveness [36–40]. The treatment strategy was thus revolutionized: Perampanel, an antagonist targeting the AMPA receptor, combined with radiotherapy, extended the survival of glioblastoma mice by 40%. The application of nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer can specifically cut off sensory nerve projections (reducing 9.8 times), and the efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors increased by 5.7 times after combined denervation. These findings indicate that the paradigm of tumor treatment has shifted from "simple anti-cancer" to systematic intervention of "cracking the four-dimensional network of neuro-immune-metabolism-tumor". Glioma activity indirectly shapes immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) through multidimensional immune reprogramming. Examples include secretome-mediated immune cell recruitment [41–44]. The CCL2/CCL7 gradient secreted by glioma stem cells (GSCs) recruits peripheral circulating plasma cells to the tumor core by binding to C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) and promotes the formation of GSCs niches. Clinical samples showed that increased plasma cell infiltration was significantly associated with poor prognosis of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) (HR=2.1, P<0.001) [45,46]. At the same time, osteopontin and CHI3L1, as specific secretion factors for diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), induce mesenchymal stem cells to differentiate into B7-H3 pericytes, enhance vascular barrier function (ABCG2 expression surges 250-fold), and polarize CD163 M2 macrophages (10-fold increase compared with normal tissues) to form a "cold" immune microenvironment. In addition, glioblast-derived IL-11 can induce CD8 T cell apoptosis by activating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling to drive astrocytes to express TRAIL (tumor necrosis factor-associated apoptosis-inducing ligand) and directly bind to T cell death receptor DR4/5 to induce apoptosis in CD8 T cells (apoptosis rate increased by 3.2 times), and knockout of Tnfsf10 (TRAIL-encoding gene) can restore anti-tumor immune response. CPQ (Carboxypeptidase Q) was specifically and highly expressed in the mesenchymal subtype GBM (AUC=91.5%), which drove macrophages to M2 polarization through the hematopoietic cell kinase / signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (HCK/STAT1) pathway, up-regulated immune checkpoints such as PD-1/TIM-3/CTLA-4 (*r*>0.68), and led to radiotherapy resistance (37% reduction in sensitivity). Transglutaminase 2 (TGM2) macrophages enriched in hypoxic necrosis area cleared apoptotic cells and inhibited inflammatory response through efferocytosis. The TGM2 inhibitor NC9 blocks this process, accumulating apoptotic cells by a factor of 2.1 and reversing immunosuppression. In response to the above mechanisms, the combination therapy has shown breakthrough potential: the AMPA receptor antagonist Perampanel blocks neuron-tumor synaptic transmission, relieves the tumor secretion of thrombospondin-1 (TSP1)-mediated immunosuppressive axis, increases pro-inflammatory tumor-associated macrophages TAMs by 1.3 times, and achieves complete tumor regression in 44% of mice with anti-PD-1 and CAR-T therapy [47,48]. Xevinapant combined with flavonoids ST-059620 synergistically induced apoptosis of GSCs (synergistic score 21.551) and overcame the evolution of drug resistance. In summary, gliomas construct a multi-level immunosuppressive barrier through the secretome-gliocyte-immune checkpoint network, and target key nodes (such as CPQ, TGM2, FcγRIIA) or block cell interactions (such as cytosis, synaptic transmission) can reverse the TME inhibitory state, providing a new paradigm for combined immunotherapy [49,50].

Gliomas systematically impair neuronal function through a multi-mechanism cascade: glutamate released by tumor cells overactivates neuronal AMPA receptors, while peritumoral oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC)-like glioma subsets overexpress potassium channel KCND2 (Neuron 2025), increasing extracellular K? concentrations by 35% and inducing epileptiform discharges (2.8-fold increased synchronicity); tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) disrupts the glutamate transporter GLT-1 function in astrocytes, resulting in a 40% decrease in glutamate clearance efficiency in the synaptic cleft and aggravating excitotoxicity. At the neural network level, TSP1 promotes abnormal synapse formation, increases neuron-tumor synaptic density by 3.1-fold in the high-functioning connectivity (HFC) region, leads to a 40% decrease in the strength of the default mode network (DMN) connection (28% decrease in metabolic activity of the posterior cingulate gyrus), and directly impairs memory and executive function (the risk of delayed cognitive recovery is increased by 52% in patients with imbalance in the dynamic characteristics of the frontal parietal network). In terms of remote regulation, glioma exosome delivery of miR-126 induces neurons to enter the cell cycle abnormally (apoptosis rate increased by 2.5 times, Nat Commun 2025), while miR-21-5p targets the Potassium-Chloride Cotransporter 2 (KCC2) chloride ion transporter of GABAergic neurons in the hypothalamus, disrupting Cl? homeostasis and inducing cachexia (30% weight loss in mice). Acetylcholine released from the basal forebrain activates calcium oscillations through glioma muscarinic receptor CHRM1/3 and counters thalamic memory encoding function. In response to the above mechanism, the AMPA receptor antagonist Perampanel combined with anti-PD-1/EGFRvIII-CAR T resulted in complete tumor regression in 44% of mice, KCND2 siRNA reduced organoid neuronal excitability by 70% (epileptic events decreased by 85%), cerebral cholinergic neurons in optogenetic silencing reduced pontine glioma by 50%, and repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improved patients' executive function score by 15–20 points—the marker was based on the "neuro-immune-metabolic axis" The multi-target intervention has officially broken through the bottleneck of traditional treatment [51–55].

This review systematically analyzes the multi-dimensional interaction network between neurons and central nervous system tumors (including primary intracranial tumors and brain metastases), and analyzes the mechanistic regulatory role of neurons in tumor progression from three dimensions: synaptic remodeling (such as the formation of neuron-tumor functional synapses), paracrine signaling axis (neurotransmitter/cytokine bidirectional communication), and tumor precursor cell evolution (neural stem cell microenvironment-driven malignant transformation). By integrating the dynamic two-way influence framework between these entities (neural activity-driven tumor proliferation vs. tumor remodeling neurological function), the cross-cutting model we construct will provide the theoretical cornerstone for the development of innovative therapies for multidisciplinary fusion strategies and ultimately achieve precise interventions for the neuro-tumor symbiotic system [56–59].

The Regulatory Role of the Nervous System in Brain Tumors

The nervous system plays a crucial role in the occurrence and development of brain tumors, which has been confirmed by many studies through animal models and clinical sample analysis. In glioma, a common primary brain tumor, neuronal activity drives tumor progression through a variety of mechanisms [60–62]. In terms of synaptic interaction mechanism, glioma cells can construct glutamatergic synaptic structures with neurons, thereby receiving excitatory inputs, such as glutamate, which promote cell depolarization and calcium influx, thereby accelerating proliferation and invasion. The related study, published in the journal Science, found that neuronal activity can strongly promote the growth of gliomas in specific circuits by constructing specific mouse models. From a paracrine perspective, factors such as neuroligin-3 and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) secreted during neuronal activity can activate oncogenic signaling pathways in tumor cells and promote tumor growth. In terms of neurotransmitter-mediated mechanisms, neurotransmitters such as glutamate and GABA act as signaling molecules between glioma cells and neurons, which can not only regulate glioma proliferation and invasion, but also regulate neurotransmitters and their receptors in turn, and reshape neurochemical signals to help tumor development. In addition, for craniopharyngioma, some studies have used chemogenetic technology to precisely regulate the electrical activity of hypothalamic endocrine neurons, and for the first time confirmed that hypothalamic neuronal activity has a two-way regulation of the development of craniopharyngioma, activation of neurons can accelerate tumor growth, and inhibition can slow down the expansion of tumor cells, the results were published in Science Translational Medicine. The regulation of brain tumors by the nervous system is a complex and multidimensional process, and in-depth exploration of these mechanisms can help to develop more effective treatment strategies for brain tumors [63–65].

Direct neuron-tumor cell synaptic connections

In the field of glioma research, the key discovery of "synaptic connections" or "pseudo synapses" has brought new light to the understanding of the mechanisms of tumor progression. Through advanced electron microscopy technology and single-cell transcriptome analysis of a large number of clinical samples, researchers have clearly observed the existence of synapse-like structures like those between glioma cells and neurons, such as glutamatergic synaptic structures [66–68]. In healthy brains, neuronal activity is triggered by action potentials, and when this electrical activity is transmitted to synapses that form with glioma cells, it directly drives electrophysiological changes in tumor cells. Taking glutamatergic synapses as an example, glutamate released by neurons acts as a neurotransmitter and specifically binds to neural ligand receptors such as alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) on the surface of glioma cells, triggering receptor conformational changes, promoting the opening of cation channels, and sodium influx depolarizes glioma cell membranes, further activating voltage-gated calcium ion channels, resulting in a large increase in intracellular calcium signaling [69–72]. At the molecular level, neuroligand receptors such as AMPA receptors play a key role in signal transduction in this process, and their activation not only triggers membrane potential changes, but also initiates a series of downstream proliferative signaling pathways. At the same time, adhesion molecules are indispensable in the formation of stable connections between neurons and glioma cells, such as neuroligin-3, which not only promote the synapse formation of neuron-glioma, but also closely related to the malignant progression and poor prognosis of glioma. In addition, the gap junction composed of connexin forms an electrical coupling network between glioma cells, and the potassium ion current generated by tumor cells after receiving neuronal electrical signals can be efficiently propagated and amplified in the tumor cell network through gap junctions, which further enhances the fluctuation of calcium signals in tumor cells and synergistically promotes tumor cell proliferation. This direct neuron-tumor cell synaptic connection has become an important driver of glioma cell proliferation and invasion, providing a promising molecular target and pathway for the development of novel targeted therapy strategies [73–77].

The BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway plays a key regulatory role in the molecular mechanisms of neuron-tumor cell synaptic connection formation described above. Immunoelectron microscopy studies showed that the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway significantly increased the number of synaptic connections between neurons and glioma cells. Specifically, when BDNF binds to the TrkB receptor on the surface of glioma cells, it triggers a downstream cascade that significantly enhances the transport of α-β amino-β 3-β-hydroxy-β 5-β methyl-β 4-β isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) receptor to the glioma cell membrane. This process not only increases the number of functional AMPAR on the cell surface, but also significantly increases the flux of calcium ions, which in turn has a bidirectional regulatory effect on electrical signal transduction, which not only enhances the efficiency of electrical signal transmission between synapses, but also inhibits abnormal electrical signal interference by regulating the opening and closing of ion channels [78-80]. Driven by the enhancement of electrical signals, the depolarization amplitude of glioma cell membrane was significantly increased, which activated the downstream mitotic-related protein kinase pathway, and ultimately accelerated tumor cell proliferation [81]. Notably, the synapses between neurons and tumor cells are dominated by AMPARergic and most neuroglioma synapses (NGS) are composed of AMPAR (Figure 1A). The structural characteristics of such synapses are typical neurogenic presynaptic membranes, which form efficient signaling units with the postsynaptic membranes of glioma cells, and jointly construct an electrophysiological regulatory network to promote the malignant progression of glioma under the synergistic effect of BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway [82–85].

Figure 1A

From a synergistic perspective of structure and function, the unique construct of the (NGS) underpins its signaling [86]. Ultrastructural studies have revealed the presence of species with high electron density in the synaptic cleft, the presence of docked vesicles in the neoplastic postsynaptic membrane band matrix, and typical postsynaptic density regions, which confer NGS with a classical synaptic signaling capacity [87]. On this basis, the impact of neurons on glioma through NGS presents a multi-dimensional and networked characteristic. Glioma cells in the brain do not exist in isolation, but form a wide network of intercellular connections with the help of tumor microtubules (TM), and realize electrical coupling and information transmission through gap junctions. When the vesicles of presynaptic neurons fuse with the anterior membrane, glutamate is released as a key neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft, where it binds specifically to the AMPA receptor on the postsynaptic membrane [88]. The ionic influx initiated by AMPA receptor activation directly generates excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which in turn drives glioma cell depolarization and excitability. In particular, synapsively stimulated glioma cell subsets can rapidly transmit calcium waves to other tumor cells through the TM network, significantly enhancing the metabolic activity and invasion ability of the entire glioma network. In addition, AMPA receptor-mediated signaling not only activates ion channels, but also directly drives the invasion and proliferation of glioma cells by regulating downstream proliferative pathways. Experimental data confirm that inhibition of AMPA receptors or blockage of gap junctions between glioma cells can effectively inhibit tumor growth; Conversely, enhancing AMPA receptor signaling accelerates tumor progression. Although the current research has preliminarily revealed the core role of NGS in glioma progression, the molecular dynamics mechanism of neurons and glioma cells through NGS interaction, the regulatory mode of signaling network and its synergistic effect with the tumor microenvironment still need more in-depth multi-omics integration research and functional validation, so as to provide theoretical support for precision treatment strategies targeting neuro-tumor synapses [89–93].

Axon guidance and tumor invasion

During tumor invasion, brain tumor cells exhibit the ability to "hijack" the molecular mechanisms related to nervous system development and repair, among which axon-guiding molecules and their receptors constitute the key molecular pathways for tumor cell invasion [94]. Axon-oriented molecules such as Netrins, Slits, Semaphorins, and Ephrins dominate axonal growth and pathway selection in nervous system development, and tumor cells translate these molecular systems into self-aggressive "navigation systems" by expressing their corresponding receptors. As shown in Figure 1B, in the case of Netrins, the UNC5 Homolog (UNC5H) and deleted in colorectal cancer (DCC) receptors on the surface of tumor cells recognize Netrin-1 signaling, and when tumor cells are in a high-concentration Netrin-1 microenvironment, the UNC5H receptor mediates a repulsive signal, prompting tumor cells to migrate to a low-concentration area [95]. The DCC receptor activates downstream pro-invasive pathways such as PI3K/AKT upon Netrin-1 binding. After binding to the Robo receptor on the surface of tumor cells, the slits protein promotes the directed migration of tumor cells by inhibiting Rho GTPase activity, remodeling the cytoskeleton, and changing cell polarity. By binding to Plexin and Neuropilin receptors, the Semaphorins family not only induces plasmopodia contraction and inhibits cell adhesion, but also activates Src family kinases to enhance the motility of tumor cells [96,97]. The interaction between Ephrins and its receptor Eph regulates the proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells through bidirectional signaling, such as the activation of Rac1 and Cdc42 by Ephrin-B2 binding to EphB4, which promotes the formation and invasion of tumor cell filopodia [98].

Figure 1B

At the same time, nerve fibers, especially white matter fiber bundles, provide a physical invasion pathway for tumor cells. The white matter fiber bundles are composed of myelinated nerve fibers arranged in parallel, and their structural order and mechanical properties provide low-resistance channels for tumor cell migration [99]. Tumor cells degrade extracellular matrix components by secreting matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), weaken the barrier role of the tissues around the fiber bundle, and use self-expressed integrins and other adhesion molecules to bind to the surface components of the fiber bundle to achieve "contact-directed migration" along the fiber bundle [100]. In glioblastoma, tumor cells often spread rapidly along the white matter fiber bundles such as the corpus callosum and the endocapsule, forming a translobeal invasion, and the synergistic effect of axon-guiding molecules and physical pathways in this process significantly enhances the dissemination ability of the tumor [101,102]. Elucidating the invasion mechanism of tumor cells using axon-guiding molecules and nerve fibers will provide important targets for the development of novel intervention strategies to inhibit tumor spread [103].

Interaction between glial cells and tumors

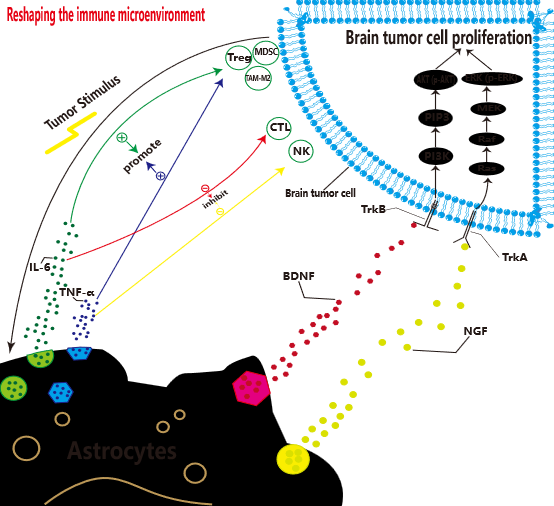

Here, we will further discuss the interaction of glial cells with tumors from the perspective of cancer neuroscience. Glial cells play an extremely complex and contradictory role in the brain tumor microenvironment, and their dynamic interaction with tumor cells profoundly affects disease progression. On the one hand, activated astrocytes promote the proliferation of immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), M2 tumor-associated macrophages (TAM-M2) by secreting pro-inflammatory factors such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and inhibit the proliferation of immunosuppressive cells such as regulatory T cells (Treg), MDSCs, and TAM-M2, and inhibit effector immune cells such as cytotoxic T cells (CTLs), Natural killer cells (NK) proliferate, thereby reshaping the immune state of the tumor microenvironment and synergizing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance [104–106]. At the same time, neurotrophic factors such as BDNF and NGF are released, and PI3K/AKT AND mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathways downstream of receptors such as TrkB and TrkA in tumor cells are activated, which directly drives tumor proliferation, as shown in Figure 1C. At the metabolic level, astrocytes provide tumor cells with energy substrates such as lactate and ketone bodies to support their rapid metabolic needs [107]. On the other hand, some astrocytes can upregulate the expression of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), forming a physical barrier to limit tumor cell invasion.

Figure 1C

Microglia and infiltrating macrophages are the main sources of TAMs, and their functional status is precisely regulated by neuronal activity and neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters such as GABA and serotonin released by neurons can induce tumoricity-promoting M2-type polarization by binding to TAM surface-specific receptors [108–110]. Taking GABA as an example, after binding to the GABAB receptor on the TAM surface, it activates the downstream cAMP/PKA pathway, inhibits NF-κB-mediated pro-inflammatory response, and upregulates the expression of arginase-1 (Arg-1) and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), promoting tumor angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, and immunosuppression [111]. In contrast, excitatory neurotransmitters such as glutamate released by neuronal activity can induce their conversion to tumor-suppressive M1 type by activating AMPA receptors on the TAM surface, enhancing antigen presentation and tumor killing ability [112].

The interaction of oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs) with tumors presents a potentially supportive characteristic [113]. Single-cell transcriptome analysis showed that OPCs could promote tumor angiogenesis through paracrine insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other pro-angiogenic factors. It also expresses platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), which binds to Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor (PDGFR) on the surface of tumor cells and activates tumor cell migration and invasion programs [114–116]. In addition, the metabolic coupling between OPCs and tumor cells may provide lipids, cholesterol and other substances to tumor cells, supporting their membrane structure remodeling and rapid proliferation [117–120]. The heterogeneous functions of glial cells and their multi-dimensional interactions with neurons and tumor cells constitute a complex network of tumor microenvironment regulation, which brings new challenges and opportunities for the development of targeted intervention strategies [121,122].

The Remodeling and Impact of Brain Tumors on the Nervous System

The existence of brain tumors not only directly destroys local brain tissue through mass effect and mechanical compression, but also profoundly induces a broad and complex remodeling process in the nervous system, which significantly affects neurological function. This remodeling involves multiple cascades of reactions from the microscopic molecular level to the macroscopic neural network level. In the tumor microenvironment, a variety of factors secreted by tumor cells (such as growth factors, inflammatory factors, excitatory neurotransmitters, proteases, etc.) can actively regulate the activity, synaptic plasticity and survival of neighboring neurons, induce abnormal synaptic formation (synaptogenesis) or elimination (synaptic pruning), and lead to the functional reorganization of local neural circuits [123]. At the same time, tumor infiltration and edema can disrupt the integrity of the white matter fiber tracts, disrupt long-distance neural connections, and force the neural network to perform compensatory functional reorganization, such as compensatory activation in the contralateral hemisphere or distal brain region. In addition, tumor-mediated imbalances in neurotransmitter homeostasis (e.g., glutamatergic excitotoxicity, impaired GABAergic inhibition) can further disrupt the excitability/inhibition balance of neural networks and induce pathological neural activities such as seizures [124–126]. It is important to note that tumor-induced neuroremodeling effects are not limited to adjacent areas of the tumor and can spread to distant brain regions and even the systemic nervous system through neural connections and humoral pathways (i.e., "telecommunication effects"), manifesting as cognitive dysfunction, neuroendocrine disorders, or behavioral changes [127]. Understanding these complex remodeling mechanisms is critical to elucidate the pathophysiological basis of clinical manifestations such as neurological deficits, epilepsy susceptibility, and cognitive decline in patients with brain tumors, and provides key targets for the development of novel therapeutic strategies aimed at preserving neurological function, mitigating the side effects of neurological injury, and even utilizing neuroplasticity for functional recovery. In-depth study of the two-way interaction between brain tumors and the nervous system, especially tumor-driven nerve remodeling, is the core research direction to improve the prognosis and quality of life of patients [128].

Structural failure and mass effect

Brain tumors directly compress the brain parenchyma through the mass effect, resulting in mechanical rupture of nerve fiber bundles (especially the arcuate fibers and the white matter pathway of the corpus callosum), resulting in focal neurological deficits. At the same time, the infiltrative growth of the tumor destroys the basement membrane of the blood vessels, induces microhemorrhage and blood-brain barrier leakage, and aggravates the angiogenic edema [129]. This structural injury triggers compensatory neuroplastic reorganization: apoptosis of GABAergic interneurons in the peritumoral cortex (40% reduction in density), which makes glutamatergic pyramidal neurons overexcited, the synchronized firing threshold decreases by 2.8 times, and the clinical manifestations are refractory epilepsy, while the distal brain region (such as the contralateral hippocampus) has a decrease in synaptic efficiency due to compensatory overload (35% decrease in LTP amplitude over a long period of time). It was accompanied by axonal myelin loss (0.15 increase in g-ratio value) and aplastic disorder (60% decrease in GAP-43 expression) [130]. More critically, tumor-associated neuroinflammation storm forms a vicious circle: glioma cells secrete IL-1β/IL-6/TNF-α triple factor, which converts microglia into a pro-inflammatory phenotype (CD68/iNOS) by activating the microglia TLR4/NF-κB pathway, which further releases reactive oxygen species (ROS) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-9), resulting in synaptophysin I degradation and neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction, and ultimately expanding the scope of neural circuit damage[131,132].

Metabolic interference

At the metabolic level, gliomas deprive neurons of energy with a "metabolic parasitism" strategy: their glycolysis rate is 8–10 times that of neurons, and they competitively uptake glucose through high expression of glucose transporter (GLUT) GLUT3/GLUT1, while secreting exosome miR-155 to inhibit neuronal glutaminase (GLS1), resulting in a 70% reduction in presynaptic glutamate synthesis and inducing neuronal energy crisis. Accumulation of tumor metabolic wastes (e.g., lactate) activates acid-sensitive ion channels (ASIC1a), inducing calcium overload apoptosis [133–135]. With neurovascular unit collapse: abnormal neovascularization lacks pericyte coverage (coverage <15%), endothelial tight junction protein claudin-5 expression is down-regulated by 50%, plasma protein leakage (fibrinogen deposition increases 3-fold), aggravated vasogenic edema; Local blood flow disturbances (40% increase in mean transit time) further limit substrate delivery. The above-mentioned multiple mechanisms synergistically lead to systemic neurological dysfunction: sensory pathway tumors activate the dorsal root ganglion transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel through the CXCL13/CXCR5 axis, inducing persistent burning pain (NRS score ≥7); Cognitive domain impairment was manifested in a 30% decrease in the functional connectivity of the default mode network (DMN), a decrease in the synchrony of prefrontal-thalamic theta oscillations, a 45% increase in the error rate of working memory, and a decline in executive function (a 60% increase in the time taken for the Trail Making Test) [136].

Tumor-induced neuroplasticity changes

Tumor-induced neuroplasticity changes are manifested by multi-level pathological restructuring: at the neural network level, the abnormal accumulation of excitatory neurotransmitters (such as glutamate) in the peritumoral microenvironment and the dysfunction of inhibitory pathways (GABAergic system) jointly disrupt the excitator/inhibition (E/I) balance, induce local neuronal hyperexcitation and synchronized discharge, resulting in tumor-associated epilepsy [137]. At the same time, distal brain regions are involved in the pathological process of motor/cognitive dysfunction through compensatory functional connection reorganization (e.g., contralateral hemisphere compensatory activation) or aberrant inhibition (e.g., default mode network node inactivation). At the synaptic level, tumor-derived factors (exosomes, MMP-9 protease) and oxidative stress (ROS) mediate synaptic structural damage, manifested by widespread loss of synapses caused by decreased dendritic spine density and degradation of postsynaptic dense matter (PSD-95), accompanied by abnormal functional synaptic efficacy—increased presynaptic glutamate release and reuptake disorder (EAAT2 downregulation) synergize with postsynaptic N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor overactivation, resulting in Ca²+-dependent excitotoxicity [138]. At the axonal level, invasive tumors lead to progressive lesions of the white matter tract, which are characterized by demyelination (Myelin Basic Protein [MBP] degradation) caused by inhibition of oligodendrocyte differentiation, disruption of nerve conduction due to Wallerian axonal degeneration, and the joint upregulation of glial scarring (chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan [CSPG] deposition) and nerve growth inhibitory factor (Nogo-A) to inhibit axonal budding and regeneration, ultimately leading to irreversible damage to long-term nerve connections. This cross-scale neuroplastic disorder together forms the core mechanism of epilepsy susceptibility, progressive neurological deficit and cognitive decline in cancer patients [139,140].

A Hub for Two-way Interaction: The Tumor Microenvironment

As the core hub of bidirectional interaction, the homeostasis of the tumor microenvironment (TME) is deeply shaped by the deep involvement of nervous system components: neurons, glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes), neurotransmitters (glutamate, GABA), and nerve fibers are not only the structural components of TME, but also the key implementers of functional regulation. At the neuro-immune-tumor axis level, sensory/sympathetic nerve fibers directly regulate the polarized phenotype (e.g., tumor-promoting M2 transformation) and T cell infiltration inhibition of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) by releasing neuropeptides (e.g., Substance P (SP), calcitonin gene-related peptide [CGRP]) and catecholamines, while the factors secreted by tumor cells (nerve growth factor[NGF], brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]) inversely upregulate the expression of neuronal axon-guiding molecules (Netrin-1, Semaphorin 4D) and induce perineural invasion (PNI) and accelerated metastasis; Conversely, inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α) released by immune cells (microglia and T cells) can activate neuronal N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and glial TLR pathways, forming a positive feedback loop between neuroinflammation and tumor progression [141–143]. At the metabolic coupling level, there is fierce competition for metabolic substrates between tumors and neuro/glial cells: glutamine, which is dependent on neuronal activity, is taken up by tumor cells in large quantities through alanine-serine-cysteine transporter 2 (ASCT2) transporters to support their tricarboxylic acid cycle replenishment, while excess lactate produced by tumor Warburg effect is injected into oligodendrocytes through monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCTs), disrupting myelin homeostasis and activating the signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) tumor promoting pathway [144]. Astrocytes provide nitrogen sources and antioxidant precursors (glutathione) to tumors through the glutamate-glutamine cycle, while glial-derived adenosine triphosphate (ATP) activates the expression of genes associated with tumor invasion through purinergic receptors (P2X7R). This multi-dimensional interaction makes TME a dynamic integration platform for neuro-immune-metabolic networks, providing a theoretical basis for the development of novel anti-tumor strategies targeting the neural microenvironment [145].

Conclusion

Our systematic review delineates the nervous system as an active driver and pathological substrate in brain tumorigenesis, establishing a paradigm-shifting model of bidirectional neuro-tumor crosstalk. Neurons directly propel tumor progression through electrochemical synapses (e.g., AMPAR-mediated glutamatergic signaling) and paracrine axes (e.g., neuroligin-3/BDNF-TrkB activation of PI3K/AKT), while gliomas co-opt developmental pathways via axonal guidance molecules (Netrins/Semaphorins) to facilitate invasion along white matter tracts. Reciprocally, tumors orchestrate multiscale neural remodeling: structural destruction of fiber bundles induces compensatory plasticity; metabolic hijacking (GLUT3-mediated glucose competition, miR-155-suppressed glutaminase) triggers neuronal energy failure; and dysregulated neuroplasticity (E/I imbalance, PSD-95 degradation, Wallerian degeneration) underlies epilepsy and cognitive decline. Critically, the tumor microenvironment emerges as a neural-immune-metabolic hub—where neurotransmitter-modulated TAM polarization (GABA-induced M2 skewing), astrocyte-mediated immunosuppression (IL-6/STAT3-TRAIL axis), and oligodendrocyte-tumor metabolic coupling (lactate/STAT3 feedforward) collectively foster therapeutic resistance. This interdependence mandates innovative targeting strategies: disrupting neuron-tumor synapses (AMPA antagonists like perampanel), blocking neurodevelopmental hijacking (Robo/Slit inhibitors), and reprogramming neuro-immune axes (GABAergic modulation of TAMs) demonstrate preclinical efficacy in suppressing growth and restoring neural function. Future therapeutics must transcend conventional cytotoxics to dismantle the dynamic quadripartite network of neurons, glia, immune cells, and tumor cells, thereby converting mechanistic insights into precision interventions that simultaneously halt oncogenesis and preserve neurological integrity.

Acknowledgements

None.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This review did not involve human participants, animal subjects, or clinical trials. Ethical approval was not required in accordance with institutional and national regulations.

Funding

This review received no specific funding.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Authors' Contributions

Cheng Xue: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing – Review & Editing.

References

2. Mack SC, Hubert CG, Miller TE, Taylor MD, Rich JN. An epigenetic gateway to brain tumor cell identity. Nat Neurosci. 2016 Jan;19(1):10–9.

3. Sampson JH, Maus MV, June CH. Immunotherapy for Brain Tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Jul 20;35(21):2450–6.

4. Boire A, Brastianos PK, Garzia L, Valiente M. Brain metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020 Jan;20(1):4–11.

5. Van den Bent MJ, Geurts M, French PJ, Smits M, Capper D, Bromberg JE, et al. Primary brain tumours in adults. The Lancet. 2023 Oct 28;402(10412):1564–79.

6. Ostrom QT, Price M, Neff C, Cioffi G, Waite KA, Kruchko C, et al. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2015-2019. Neuro Oncol. 2022 Oct 5;24(Suppl 5):v1–95.

7. Zaidi M. Skeletal remodeling in health and disease. Nat Med. 2007 Jul;13(7):791–801.

8. Sisk CL, Foster DL. The neural basis of puberty and adolescence. Nat Neurosci. 2004 Oct;7(10):1040–7.

9. Gamble KL, Berry R, Frank SJ, Young ME. Circadian clock control of endocrine factors. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014 Aug;10(8):466–75.

10. Schiller M, Ben-Shaanan TL, Rolls A. Neuronal regulation of immunity: why, how and where? Nat Rev Immunol. 2021 Jan;21(1):20–36.

11. Gizowski C, Bourque CW. The neural basis of homeostatic and anticipatory thirst. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018 Jan;14(1):11–25

12. Venkatesh HS, Morishita W, Geraghty AC, Silverbush D, Gillespie SM, Arzt M, et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature. 2019 Sep;573(7775):539–45.

13. Mauffrey P, Tchitchek N, Barroca V, Bemelmans AP, Firlej V, Allory Y, et al. Progenitors from the central nervous system drive neurogenesis in cancer. Nature. 2019 May;569(7758):672–8.

14. Chen W, Li C, Liang W, Li Y, Zou Z, Xie Y, et al. The Roles of Optogenetics and Technology in Neurobiology: A Review. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022 Apr 19;14:867863.

15. Versijpt J, Paemeleire K, Reuter U, MaassenVanDenBrink A. Calcitonin gene-related peptide-targeted therapy in migraine: current role and future perspectives. Lancet. 2025 Mar 22;405(10483):1014–26.

16. Venkataramani V, Tanev DI, Strahle C, Studier-Fischer A, Fankhauser L, Kessler T, et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature. 2019 Sep;573(7775):532–8.

17. Perner C, Flayer CH, Zhu X, Aderhold PA, Dewan ZNA, Voisin T, et al. Substance P Release by Sensory Neurons Triggers Dendritic Cell Migration and Initiates the Type-2 Immune Response to Allergens. Immunity. 2020 Nov 17;53(5):1063–77.e7.

18. Yazdankhah M, Shang P, Ghosh S, Hose S, Liu H, Weiss J, et al. Role of glia in optic nerve. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2021 Mar;81:100886.

19. Liu DD, He JQ, Sinha R, Eastman AE, Toland AM, Morri M, et al. Purification and characterization of human neural stem and progenitor cells. Cell. 2023 Mar 16;186(6):1179–94.e15.

20. Taylor KR, Monje M. Neuron-oligodendroglial interactions in health and malignant disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023 Dec;24(12):733–46.

21. Monje M, Borniger JC, D'Silva NJ, Deneen B, Dirks PB, Fattahi F, et al. Roadmap for the Emerging Field of Cancer Neuroscience. Cell. 2020 Apr 16;181(2):219–22.

22. Winkler F, Venkatesh HS, Amit M, Batchelor T, Demir IE, Deneen B, et al. Cancer neuroscience: State of the field, emerging directions. Cell. 2023 Apr 13;186(8):1689–707.

23. Shi DD, Guo JA, Hoffman HI, Su J, Mino-Kenudson M, Barth JL, et al. Therapeutic avenues for cancer neuroscience: translational frontiers and clinical opportunities. Lancet Oncol. 2022 Feb;23(2):e62–74.

24. Demir IE, Mota Reyes C, Alrawashdeh W, Ceyhan GO, Deborde S, Friess H, et al. Future directions in preclinical and translational cancer neuroscience research. Nat Cancer. 2021 Nov;1:1027–31.

25. Venkatesh HS, Johung TB, Caretti V, Noll A, Tang Y, Nagaraja S, et al. Neuronal Activity Promotes Glioma Growth through Neuroligin-3 Secretion. Cell. 2015 May 7;161(4):803–16

26. Venkataramani V, Tanev DI, Strahle C, Studier-Fischer A, Fankhauser L, Kessler T, et al. Glutamatergic synaptic input to glioma cells drives brain tumour progression. Nature. 2019 Sep;573(7775):532–8.

27. Venkatesh HS, Morishita W, Geraghty AC, Silverbush D, Gillespie SM, Arzt M, et al. Electrical and synaptic integration of glioma into neural circuits. Nature. 2019 Sep;573(7775):539–45.

28. Zeng Q, Michael IP, Zhang P, Saghafinia S, Knott G, Jiao W, et al. Synaptic proximity enables NMDAR signalling to promote brain metastasis. Nature. 2019 Sep;573(7775):526–31

29. Monje M. Synaptic Communication in Brain Cancer. Cancer Res. 2020 Jul 15;80(14):2979–82.

30. Mancusi R, Monje M. The neuroscience of cancer. Nature. 2023 Jun;618(7965):467–79.

31. Jung E, Alfonso J, Osswald M, Monyer H, Wick W, Winkler F. Emerging intersections between neuroscience and glioma biology. Nat Neurosci. 2019 Dec;22(12):1951–60.

32. Broekman ML, Maas SLN, Abels ER, Mempel TR, Krichevsky AM, Breakefield XO. Multidimensional communication in the microenvirons of glioblastoma. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018 Aug;14(8):482–95.

33. Achrol AS, Rennert RC, Anders C, Soffietti R, Ahluwalia MS, Nayak L, et al. Brain metastases. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019 Jan 17;5(1):5.

34. Klemm F, Maas RR, Bowman RL, Kornete M, Soukup K, Nassiri S, et al. Interrogation of the Microenvironmental Landscape in Brain Tumors Reveals Disease-Specific Alterations of Immune Cells. Cell. 2020 Jun 25;181(7):1643–60.e17.

35. Bikfalvi A, da Costa CA, Avril T, Barnier JV, Bauchet L, Brisson L, et al. Challenges in glioblastoma research: focus on the tumor microenvironment. Trends Cancer. 2023 Jan;9(1):9–27.

36. Hanahan D, Monje M. Cancer hallmarks intersect with neuroscience in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2023 Mar 13;41(3):573–80

37. Hoogstrate Y, Draaisma K, Ghisai SA, van Hijfte L, Barin N, de Heer I, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals tumor microenvironment changes in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2023 Apr 10;41(4):678–92.e7.

38. Khanmammadova N, Islam S, Sharma P, Amit M. Neuro-immune interactions and immuno-oncology. Trends Cancer. 2023 Aug;9(8):636–49.

39. Bejarano L, Kauzlaric A, Lamprou E, Lourenco J, Fournier N, Ballabio M, et al. Interrogation of endothelial and mural cells in brain metastasis reveals key immune-regulatory mechanisms. Cancer Cell. 2024 Mar 11;42(3):378–95.e10.

40. Greenwald AC, Darnell NG, Hoefflin R, Simkin D, Mount CW, Gonzalez Castro LN, et al. Integrative spatial analysis reveals a multi-layered organization of glioblastoma. Cell. 2024 May 9;187(10):2485–501.e26.

41. Pan Y, Hysinger JD, Barron T, Schindler NF, Cobb O, Guo X, et al. NF1 mutation drives neuronal activity-dependent initiation of optic glioma. Nature. 2021 Jun;594(7862):277–82.

42. Taylor KR, Barron T, Hui A, Spitzer A, Yalçin B, Ivec AE, et al. Glioma synapses recruit mechanisms of adaptive plasticity. Nature. 2023 Nov;623(7986):366–74.

43. Venkatesh HS, Tam LT, Woo PJ, Lennon J, Nagaraja S, Gillespie SM, et al. Targeting neuronal activity-regulated neuroligin-3 dependency in high-grade glioma. Nature. 2017 Sep 28;549(7673):533–7.

44. Chen P, Wang W, Liu R, Lyu J, Zhang L, Li B, et al. Olfactory sensory experience regulates gliomagenesis via neuronal IGF1. Nature. 2022 Jun;606(7914):550–6.

45. Hambardzumyan D, Gutmann DH, Kettenmann H. The role of microglia and macrophages in glioma maintenance and progression. Nat Neurosci. 2016 Jan;19(1):20–7.

46. Li W, Graeber MB. The molecular profile of microglia under the influence of glioma. Neuro Oncol. 2012 Aug;14(8):958–78.

47. Li T, Xu D, Ruan Z, Zhou J, Sun W, Rao B, et al. Metabolism/Immunity Dual-Regulation Thermogels Potentiating Immunotherapy of Glioblastoma Through Lactate-Excretion Inhibition and PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2024 May;11(18):e2310163.

48. Jayaram MA, Phillips JJ. Role of the Microenvironment in Glioma Pathogenesis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2024 Jan 24;19:181–201.

49. Ravi VM, Will P, Kueckelhaus J, Sun N, Joseph K, Salié H, et al. Spatially resolved multi-omics deciphers bidirectional tumor-host interdependence in glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2022 Jun 13;40(6):639–55.e13.

50. Wang Q, Hu B, Hu X, Kim H, Squatrito M, Scarpace Let al. Tumor Evolution of Glioma-Intrinsic Gene Expression Subtypes Associates with Immunological Changes in the Microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2017 Jul 10;32(1):42–56.e6.

51. Yao M, Ventura PB, Jiang Y, Rodriguez FJ, Wang L, Perry JSA, et al. Astrocytic trans-Differentiation Completes a Multicellular Paracrine Feedback Loop Required for Medulloblastoma Tumor Growth. Cell. 2020 Feb 6;180(3):502–20.e19.

52. de Pablos-Aragoneses A, Valiente M. An Inbred Ecosystem that Supports Medulloblastoma. Immunity. 2020 Mar 17;52(3):431–3.

53. van Hooren L, Handgraaf SM, Kloosterman DJ, Karimi E, van Mil LWHG, Gassama AA, et al. CD103+ regulatory T cells underlie resistance to radio-immunotherapy and impair CD8+ T cell activation in glioblastoma. Nat Cancer. 2023 May;4(5):665–81.

54. Andersen BM, Faust Akl C, Wheeler MA, Chiocca EA, Reardon DA, Quintana FJ. Glial and myeloid heterogeneity in the brain tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Cancer. 2021 Dec;21(12):786–802.

55. Zhu C., Kros J. M., Cheng C., and Mustafa D., “The Contribution of Tumor?Associated Macrophages in Glioma Neo?Angiogenesis and Implications for Anti?Angiogenic Strategies,” Neuro?Oncology 19, no. 11 (2017): 1435–46.

56. Wang X, Ding H, Li Z, Peng Y, Tan H, Wang C, et al. Exploration and functionalization of M1-macrophage extracellular vesicles for effective accumulation in glioblastoma and strong synergistic therapeutic effects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Mar 16;7(1):74.

57. Buckingham SC, Campbell SL, Haas BR, Montana V, Robel S, Ogunrinu T, et al. Glutamate release by primary brain tumors induces epileptic activity. Nat Med. 2011 Sep 11;17(10):1269–74.

58. Meyer-Baese A, Jütten K, Meyer-Baese U, Amani AM, Malberg H, Stadlbauer A, et al. Controllability and Robustness of Functional and Structural Connectomic Networks in Glioma Patients. Cancers (Basel). 2023 May 11;15(10):2714.

59. Krishna S, Choudhury A, Keough MB, Seo K, Ni L, Kakaizada S, et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature. 2023 May;617(7961):599–607.

60. Aabedi AA, Lipkin B, Kaur J, Kakaizada S, Valdivia C, Reihl S, et al. Functional alterations in cortical processing of speech in glioma-infiltrated cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Nov 16;118(46):e2108959118.

61. Teplyuk NM, Uhlmann EJ, Wong AH, Karmali P, Basu M, Gabriely G, et al. MicroRNA-10b inhibition reduces E2F1-mediated transcription and miR-15/16 activity in glioblastoma. Oncotarget. 2015 Feb 28;6(6):3770-83.

62. Herrup K, Yang Y. Cell cycle regulation in the postmitotic neuron: oxymoron or new biology? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 May;8(5):368–78.

63. Zhu Y, Lu Y, Zhang Q, Liu JJ, Li TJ, Yang JR, et al. MicroRNA-26a/b and their host genes cooperate to inhibit the G1/S transition by activating the pRb protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012 May;40(10):4615–25.

64. Kim H, Huang W, Jiang X, Pennicooke B, Park PJ, Johnson MD. Integrative genome analysis reveals an oncomir/oncogene cluster regulating glioblastoma survivorship. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Feb 2;107(5):2183–8.

65. Johnston MF, Simon SA, Ramón F. Interaction of anaesthetics with electrical synapses. Nature. 1980 Jul 31;286(5772):498–500.

66. Südhof TC. Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature. 2008 Oct 16;455(7215):903–11.

67. Harnett MT, Makara JK, Spruston N, Kath WL, Magee JC. Synaptic amplification by dendritic spines enhances input cooperativity. Nature. 2012 Nov 22;491(7425):599–602.

68. Trenholm S, McLaughlin AJ, Schwab DJ, Turner MH, Smith RG, Rieke F, et al. Nonlinear dendritic integration of electrical and chemical synaptic inputs drives fine-scale correlations. Nat Neurosci. 2014 Dec;17(12):1759–66.

69. Perea G, Navarrete M, Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 2009 Aug;32(8):421–31.

70. Dolphin AC, Lee A. Presynaptic calcium channels: specialized control of synaptic neurotransmitter release. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2020 Apr;21(4):213–29.

71. Pereda AE. Electrical synapses and their functional interactions with chemical synapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014 Apr;15(4):250–63.

72. Tritsch NX, Granger AJ, Sabatini BL. Mechanisms and functions of GABA co-release. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016 Mar;17(3):139–45.

73. Nagai J, Rajbhandari AK, Gangwani MR, Hachisuka A, Coppola G, Masmanidis SC, et al. Hyperactivity with Disrupted Attention by Activation of an Astrocyte Synaptogenic Cue. Cell. 2019 May 16;177(5):1280–92.e20.

74. Ghorbani S, Yong VW. The extracellular matrix as modifier of neuroinflammation and remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2021 Aug 17;144(7):1958–73.

75. Kaneko M, Stryker MP. Production of brain-derived neurotrophic factor gates plasticity in developing visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 Jan 17;120(3):e2214833120.

76. Pei Z, Guo X, Zheng F, Yang Z, Li T, Yu Z, et al. Xuefu Zhuyu decoction promotes synaptic plasticity by targeting miR-191a-5p/BDNF-TrkB axis in severe traumatic brain injury. Phytomedicine. 2024 Jul;129:155566.

77. Lin SC, Bergles DE. Synaptic signaling between GABAergic interneurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nat Neurosci. 2004 Jan;7(1):24–32.

78. Nicoll RA, Tomita S, Bredt DS. Auxiliary subunits assist AMPA-type glutamate receptors. Science. 2006 Mar 3;311(5765):1253–6.

79. Derkach VA, Oh MC, Guire ES, Soderling TR. Regulatory mechanisms of AMPA receptors in synaptic plasticity. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007 Feb;8(2):101–13.

80. Harris KM, Weinberg RJ. Ultrastructure of synapses in the mammalian brain. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012 May 1;4(5):a005587.

81. Winkler F, Wick W. Harmful networks in the brain and beyond. Science. 2018 Mar 9;359(6380):1100–01.

82. Osswald M, Jung E, Sahm F, Solecki G, Venkataramani V, Blaes J, et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature. 2015 Dec 3;528(7580):93–8.

83. Xie R, Kessler T, Grosch J, Hai L, Venkataramani V, Huang L, et al. Tumor cell network integration in glioma represents a stemness feature. Neuro Oncol. 2021 May 5;23(5):757–69.

84. Dupuis JP, Nicole O, Groc L. NMDA receptor functions in health and disease: Old actor, new dimensions. Neuron. 2023 Aug 2;111(15):2312–28.

85. Kalia LV, Kalia SK, Salter MW. NMDA receptors in clinical neurology: excitatory times ahead. Lancet Neurol. 2008 Aug;7(8):742–55.

86. Li L, Zeng Q, Bhutkar A, Galván JA, Karamitopoulou E, Noordermeer D, et al. GKAP Acts as a Genetic Modulator of NMDAR Signaling to Govern Invasive Tumor Growth. Cancer Cell. 2018 Apr 9;33(4):736–51.

87. Merlo LM, Pepper JW, Reid BJ, Maley CC. Cancer as an evolutionary and ecological process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006 Dec;6(12):924–35.

88. Nguyen DX, Bos PD, Massagué J. Metastasis: from dissemination to organ-specific colonization. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009 Apr;9(4):274–84.

89. Liu Y, Cao X. Characteristics and Significance of the Pre-metastatic Niche. Cancer Cell. 2016 Nov 14;30(5):668–81.

90. Massagué J, Obenauf AC. Metastatic colonization by circulating tumour cells. Nature. 2016 Jan 21;529(7586):298–306.

91. Li L, Hanahan D. Hijacking the neuronal NMDAR signaling circuit to promote tumor growth and invasion. Cell. 2013 Mar 28;153(1):86–100.

92. Yin J, Tu G, Peng M, Zeng H, Wan X, Qiao Y, et al. GPER-regulated lncRNA-Glu promotes glutamate secretion to enhance cellular invasion and metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. FASEB J. 2020 Mar;34(3):4557–72.

93. Bayer KU, De Koninck P, Leonard AS, Hell JW, Schulman H. Interaction with the NMDA receptor locks CaMKII in an active conformation. Nature. 2001 Jun 14;411(6839):801–5.

94. Matta JA, Ashby MC, Sanz-Clemente A, Roche KW, Isaac JT. mGluR5 and NMDA receptors drive the experience- and activity-dependent NMDA receptor NR2B to NR2A subunit switch. Neuron. 2011 Apr 28;70(2):339–51.

95. Grosshans DR, Clayton DA, Coultrap SJ, Browning MD. LTP leads to rapid surface expression of NMDA but not AMPA receptors in adult rat CA1. Nat Neurosci. 2002 Jan;5(1):27–33

96. Terashima A, Pelkey KA, Rah JC, Suh YH, Roche KW, Collingridge GL, et al. An essential role for PICK1 in NMDA receptor-dependent bidirectional synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2008 Mar 27;57(6):872–82.

97. Lee SJ, Escobedo-Lozoya Y, Szatmari EM, Yasuda R. Activation of CaMKII in single dendritic spines during long-term potentiation. Nature. 2009 Mar 19;458(7236):299–304.

98. Harward SC, Hedrick NG, Hall CE, Parra-Bueno P, Milner TA, Pan E, et al. Autocrine BDNF-TrkB signalling within a single dendritic spine. Nature. 2016 Oct 6;538(7623):99–103.

99. Chen HJ, Rojas-Soto M, Oguni A, Kennedy MB. A synaptic Ras-GTPase activating protein (p135 SynGAP) inhibited by CaM kinase II. Neuron. 1998 May;20(5):895–904.

100. Kornau HC, Schenker LT, Kennedy MB, Seeburg PH. Domain interaction between NMDA receptor subunits and the postsynaptic density protein PSD-95. Science. 1995 Sep 22;269(5231):1737–40

101. Naisbitt S, Kim E, Tu JC, Xiao B, Sala C, Valtschanoff J, et al. Shank, a novel family of postsynaptic density proteins that binds to the NMDA receptor/PSD-95/GKAP complex and cortactin. Neuron. 1999 Jul;23(3):569–82.

102. Krapivinsky G, Medina I, Krapivinsky L, Gapon S, Clapham DE. SynGAP-MUPP1-CaMKII synaptic complexes regulate p38 MAP kinase activity and NMDA receptor-dependent synaptic AMPA receptor potentiation. Neuron. 2004 Aug 19;43(4):563–74.

103. Schmeisser MJ, Ey E, Wegener S, Bockmann J, Stempel AV, Kuebler A, et al. Autistic-like behaviours and hyperactivity in mice lacking ProSAP1/Shank2. Nature. 2012 Apr 29;486(7402):256–60.

104. Ma Z, Liu K, Li XR, Wang C, Liu C, Yan DY, et al. Alpha-synuclein is involved in manganese-induced spatial memory and synaptic plasticity impairments via TrkB/Akt/Fyn-mediated phosphorylation of NMDA receptors. Cell Death Dis. 2020 Oct 8;11(10):834.

105. Cai Q, Zeng M, Wu X, Wu H, Zhan Y, Tian R, et al. CaMKII?-driven, phosphatase-checked postsynaptic plasticity via phase separation. Cell Res. 2021 Jan;31(1):37–51.

106. Compans B, Camus C, Kallergi E, Sposini S, Martineau M, Butler C, et al. NMDAR-dependent long-term depression is associated with increased short term plasticity through autophagy mediated loss of PSD-95. Nat Commun. 2021 May 14;12(1):2849.

107. Yao M, Meng M, Yang X, Wang S, Zhang H, Zhang F, et al. POSH regulates assembly of the NMDAR/PSD-95/Shank complex and synaptic function. Cell Rep. 2022 Apr 5;39(1):110642.

108. Shen Z, Sun D, Savastano A, Varga SJ, Cima-Omori MS, Becker S, et al. Multivalent Tau/PSD-95 interactions arrest in vitro condensates and clusters mimicking the postsynaptic density. Nat Commun. 2023 Oct 27;14(1):6839.

109. Park ES, Kim SJ, Kim SW, Yoon SL, Leem SH, Kim SB, et al. Cross-species hybridization of microarrays for studying tumor transcriptome of brain metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Oct 18;108(42):17456–61.

110. Neman J, Termini J, Wilczynski S, Vaidehi N, Choy C, Kowolik CM, et al. Human breast cancer metastases to the brain display GABAergic properties in the neural niche. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014 Jan 21;111(3):984–9.

111. Qu F, Brough SC, Michno W, Madubata CJ, Hartmann GG, Puno A, et al. Crosstalk between small-cell lung cancer cells and astrocytes mimics brain development to promote brain metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2023 Oct;25(10):1506–19.

112. Vílchez-Acosta A, Manso Y, Cárdenas A, Elias-Tersa A, Martínez-Losa M, Pascual M, et al. Specific contribution of Reelin expressed by Cajal-Retzius cells or GABAergic interneurons to cortical lamination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2022 Sep 13;119(37):e2120079119.

113. Del Río JA, Heimrich B, Borrell V, Förster E, Drakew A, Alcántara S, et al. A role for Cajal-Retzius cells and reelin in the development of hippocampal connections. Nature. 1997 Jan 2;385(6611):70–4.

114. Huang-Hobbs E, Cheng YT, Ko Y, Luna-Figueroa E, Lozzi B, Taylor KR, et al. Remote neuronal activity drives glioma progression through SEMA4F. Nature. 2023 Jul;619(7971):844–50.

115. Söhl G, Maxeiner S, Willecke K. Expression and functions of neuronal gap junctions. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005 Mar;6(3):191–200.

116. Alcamí P, Pereda AE. Beyond plasticity: the dynamic impact of electrical synapses on neural circuits. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2019 May;20(5):253–71.

117. Giaume C, Naus CC, Sáez JC, Leybaert L. Glial Connexins and Pannexins in the Healthy and Diseased Brain. Physiol Rev. 2021 Jan 1;101(1):93–145.

118. Sofroniew MV. HepaCAM shapes astrocyte territories, stabilizes gap-junction coupling, and influences neuronal excitability. Neuron. 2021 Aug 4;109(15):2365–7.

119. Pedroni A, Dai YE, Lafouasse L, Chang W, Srivastava I, Del Vecchio L, et al. Neuroprotective gap-junction-mediated bystander transformations in the adult zebrafish spinal cord after injury. Nat Commun. 2024 May 21;15(1):4331.

120. Ni C, Lou X, Yao X, Wang L, Wan J, Duan X, et al. ZIP1+ fibroblasts protect lung cancer against chemotherapy via connexin-43 mediated intercellular Zn2+ transfer. Nat Commun. 2022 Oct 7;13(1):5919.

121. Hausmann D, Hoffmann DC, Venkataramani V, Jung E, Horschitz S, Tetzlaff SK, et al. Autonomous rhythmic activity in glioma networks drives brain tumour growth. Nature. 2023 Jan;613(7942):179–86.

122. Jung E, Osswald M, Blaes J, Wiestler B, Sahm F, Schmenger T, et al. Tweety-Homolog 1 Drives Brain Colonization of Gliomas. J Neurosci. 2017 Jul 19;37(29):6837–50.

123. Venkataramani V, Schneider M, Giordano FA, Kuner T, Wick W, Herrlinger U, et al. Disconnecting multicellular networks in brain tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022 Aug;22(8):481–91.

124. Schneider M, Vollmer L, Potthoff AL, Ravi VM, Evert BO, Rahman MA, et al. Meclofenamate causes loss of cellular tethering and decoupling of functional networks in glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2021 Nov 2;23(11):1885–97.

125. Gritsenko PG, Atlasy N, Dieteren CEJ, Navis AC, Venhuizen JH, Veelken C, et al. p120-catenin-dependent collective brain infiltration by glioma cell networks. Nat Cell Biol. 2020 Jan;22(1):97–107.

126. Varn FS, Johnson KC, Martinek J, Huse JT, Nasrallah MP, Wesseling P, et al; GLASS Consortium. Glioma progression is shaped by genetic evolution and microenvironment interactions. Cell. 2022 Jun 9;185(12):2184–99.e16.

127. Yoshida T, Yamagata A, Imai A, Kim J, Izumi H, Nakashima S, et al. Canonical versus non-canonical transsynaptic signaling of neuroligin 3 tunes development of sociality in mice. Nat Commun. 2021 Mar 23;12(1):1848.

128. Varghese M, Keshav N, Jacot-Descombes S, Warda T, Wicinski B, Dickstein DL, et al. Autism spectrum disorder: neuropathology and animal models. Acta Neuropathol. 2017 Oct;134(4):537–66.

129. Hörnberg H, Pérez-Garci E, Schreiner D, Hatstatt-Burklé L, Magara F, Baudouin S, et al. Rescue of oxytocin response and social behaviour in a mouse model of autism. Nature. 2020 Aug;584(7820):252–6.

130. Liu R, Qin XP, Zhuang Y, Zhang Y, Liao HB, Tang JC, et al. Glioblastoma recurrence correlates with NLGN3 levels. Cancer Med. 2018 Jul;7(7):2848–59.

131. Camporesi E, Nilsson J, Vrillon A, Cognat E, Hourregue C, Zetterberg H, et al. Quantification of the trans-synaptic partners neurexin-neuroligin in CSF of neurodegenerative diseases by parallel reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. EBioMedicine. 2022 Jan;75:103793.

132. Dang NN, Li XB, Zhang M, Han C, Fan XY, Huang SH. NLGN3 Upregulates Expression of ADAM10 to Promote the Cleavage of NLGN3 via Activating the LYN Pathway in Human Gliomas. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021 Aug 16;9:662763.

133. Kuhn PH, Colombo AV, Schusser B, Dreymueller D, Wetzel S, Schepers U, et al. Systematic substrate identification indicates a central role for the metalloprotease ADAM10 in axon targeting and synapse function. Elife. 2016 Jan 23;5:e12748.

134. Wang Y, Liu YY, Chen MB, Cheng KW, Qi LN, Zhang ZQ, et al. Neuronal-driven glioma growth requires G?i1 and G?i3. Theranostics. 2021 Jul 25;11(17):8535–49.

135. Jain P, Surrey LF, Straka J, Luo M, Lin F, Harding B, et al. Novel FGFR2-INA fusion identified in two low-grade mixed neuronal-glial tumors drives oncogenesis via MAPK and PI3K/mTOR pathway activation. Acta Neuropathol. 2018 Jul;136(1):167–9.

136. Luszczak S, Kumar C, Sathyadevan VK, Simpson BS, Gately KA, Whitaker HC, et al. PIM kinase inhibition: co-targeted therapeutic approaches in prostate cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020 Jan 31;5(1):7.

137. Crino PB. mTOR: A pathogenic signaling pathway in developmental brain malformations. Trends Mol Med. 2011 Dec;17(12):734–42.

138. Ren AA, Snellings DA, Su YS, Hong CC, Castro M, Tang AT, et al. PIK3CA and CCM mutations fuel cavernomas through a cancer-like mechanism. Nature. 2021 Jun;594(7862):271–6.

139. Raman M, Chen W, Cobb MH. Differential regulation and properties of MAPKs. Oncogene. 2007 May 14;26(22):3100–12.

140. Deschênes-Simard X, Kottakis F, Meloche S, Ferbeyre G. ERKs in cancer: friends or foes? Cancer Res. 2014 Jan 15;74(2):412–9.

141. Goel HL, Mercurio AM. VEGF targets the tumour cell. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013 Dec;13(12):871–82.

142. Cherry EM, Lee DW, Jung JU, Sitcheran R. Tumor necrosis factor-like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) promotes glioma cell invasion through induction of NF-?B-inducing kinase (NIK) and noncanonical NF-?B signaling. Mol Cancer. 2015 Jan 27;14(1):9.

143. Schmidt D, Textor B, Pein OT, Licht AH, Andrecht S, Sator-Schmitt M, et al. Critical role for NF-kappaB-induced JunB in VEGF regulation and tumor angiogenesis. EMBO J. 2007 Feb 7;26(3):710–9.

144. Varfolomeev E, Blankenship JW, Wayson SM, Fedorova AV, Kayagaki N, Garg P, et al. IAP antagonists induce autoubiquitination of c-IAPs, NF-kappaB activation, and TNFalpha-dependent apoptosis. Cell. 2007 Nov 16;131(4):669–81.

145. Liang J, Saad Y, Lei T, Wang J, Qi D, Yang Q, et al. MCP-induced protein 1 deubiquitinates TRAF proteins and negatively regulates JNK and NF-kappaB signaling. J Exp Med. 2010 Dec 20;207(13):2959–73.