Abstract

Background: Postoperative functional impairments are common in patients with oral cancer following surgery. Furthermore, these patients frequently experience fatigue and anxiety, which are strongly linked to a lower quality of life (QOL). The goal of our study was to investigate the effectiveness of comprehensive nursing intervention on alleviating postoperative fatigue and anxiety in patients with oral cancer.

Methods: A cohort of one hundred sixty patients who had surgery for oral cancer was randomly split into experimental and control groups. The research focused on evaluating fatigue and anxiety levels in postoperative oral cancer patients, both before and after the nursing intervention, in the pre-test and post-test groups. The methods utilized to measure the degree of fatigue and anxiety were the Multidimensional Exhaustion Inventory (MFI-20) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) scale respectively.

Results: The analysis revealed a statistically significant difference in educational status (p<0.01), occupation (p<0.01), monthly income (p<0.01), and cancer stage (p<0.01) between the experimental and control groups. Post-nursing intervention, the experimental group exhibited a significant decline in descriptive characteristics (p<0.04 vs. p=0.13) and in the mean and standard deviation of fatigue levels before and after the intervention (p<0.03 vs. p=0.16) compared to the control groups. However, there was no statistically significant reduction noted in the descriptive characteristics (p=0.10 vs. p=0.10), nor in the mean and standard deviation of anxiety levels before and after the tests (p=0.16 vs. p=0.28) when comparing the groups.

Conclusion: By implementing nursing interventions in regular practice, healthcare providers can help to alleviate fatigue and anxiety, which can significantly boost the QOL for postoperative patients with oral cancer. A future study should focus on improving the effectiveness of these nursing interventions over an extended period.

Keywords

Postoperative oral cancer, Nursing intervention, Fatigue, Anxiety, MFI-20 scale, BAI scale

Introduction

The exponential rise in non-communicable diseases in the twenty-first century is regarded as a major public health concern endangering both the socioeconomic well-being of communities and the health of their citizens. Chronic respiratory diseases, cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease are the most prevalent non-communicable disease types. Head and neck cancer is among the most commonly occurring cancers [1]. In this category, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is identified as the sixth most prevalent cancer worldwide, accounting for about 900,000 cases of incidence and almost 400,000 cases of mortality, respectively [2]. The collective term HNSCC is used for the majority of head and neck tumors that originate from the mucosal epithelium in the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx [3]. In Asia, where HNCs are reported for 57.5% of all global cases, up to 30% of all cancer cases occur in India [4]. Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is identified as the 17th most widespread cancer on a global scale, accounting for over 90% of all malignant neoplasms of the oral cavity [5]. The most common OSCC sites are the tongue and buccal cavity, followed by the lip and palate. The risk factors for OSCC, which include alcohol, smoking, having different chewing habits (Betel quid, gutka, pan masala, etc), and having high-risk HPV infections, are geographic location-specific [6].

One common symptom that cancer patients experience is fatigue. The term cancer-related fatigue (CRF) describes a distressing and persistent experience of physical, emotional, and/or cognitive tiredness that is associated with cancer or its treatment. This exhaustion is disproportionate to recent physical activity and affects normal daily activities [7]. Fatigue affects about 50% of the cancer patients during or after their therapy. These cancer-related symptoms may cause a decline in treatment adherence, a worse quality of life (QOL), and an even lower chance of survival than in patients who are not affected [8].

Anxiety is an unpleasant emotional condition that manifests as excessive and subjective discomfort, fear of the future, and both intentional and involuntary physical manifestations, such as chemical and biological changes [9]. Among cancer patients, anxiety and depression are prevalent mental health issues. Numerous factors have been linked to the incidence of anxiety in cancer patients. Research has indicated that several factors, including age, gender, educational attainment, and others, are significantly correlated with patients' depressive symptoms. Poor mental health, such as depressive symptoms, anxiety, and demoralization, is strongly and consistently correlated with stigma among cancer patients [10]. Coexisting anxiety or depression can affect the response of the patient toward pain perception [11]. Previous research has linked psychological suffering, including depression, somatization, anxiety, and poor sleep quality, to fatigue. It's been proposed that going through cancer therapy itself has a role in the development of fatigue [12].

There is a dearth of studies describing the fatigue and anxiety of postoperative patients with oral cancer in India. To the best of our knowledge, this study appears to be the first of its kind in India that examines fatigue and anxiety in this specific patient population after surgery. The aim of the research was to evaluate the impact of a comprehensive nursing intervention on alleviating postoperative fatigue and anxiety in patients with oral cancer.

Material and Methods

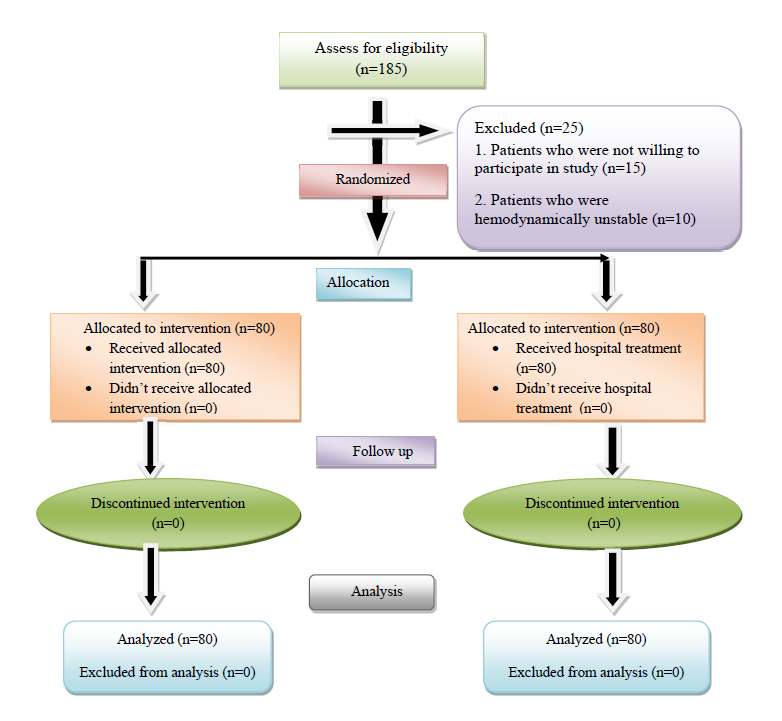

A total of 160 patients (97 males and 63 females) with stage I to IV OSCC who underwent surgery were included in this prospective cohort research between September 2022 and February 2024. The research adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Desh Bhagat University (DBU/RC/2023/2338). It was carried out at the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Regional Cancer Centre located in Agartala, Tripura, India. This investigation adopted a randomized control framework and a quantitative research approach to measure the extent of fatigue and anxiety experienced by patients following oral cancer surgery. The procedure for patient enrollment selection is depicted in the flowchart presented in Figure 1.

Data collection

Patients' clinical and demographic details were documented after their enrollment in the research. The information gathered consisted of age, gender, religion, educational status, occupation, monthly income, marital status, types of surgical interventions, cancer stage, tumor metastasis, and the primary site affected.

Comprehensive nursing intervention

Comprehensive nursing intervention involves supporting relaxation techniques, mouth opening exercises, active and passive range of motion, stretching activities, ensuring proper posture, chin tucks, and shoulder blade squeezes, conducted by research personnel. Furthermore, it offers educational resources regarding the use of thyme honey, dental care, and counselling for patients recovering from oral cancer surgery. The experimental group engaged with a video and PowerPoint presentation, while the control group was instructed to follow the hospital's standard care guidelines. The nursing intervention lasted between ten and fifteen minutes, and the educational intervention was thirty minutes long. Patients were advised to perform the exercise nine to ten times daily for five days in a row, with the opportunity to practice the exercise as necessary.

Assessment of fatigue

The research utilized the 20-item Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) as a self-report measure to determine the fatigue levels experienced by the patients involved. Five subscales make up this measure: mental, physical, reduced activity, decreased motivation, and general fatigue. All responses are provided on a 5-point Likert scale. All ratings were converted linearly from 0 (no fatigue) to 100 (the highest amount of fatigue). At least half of the items required a response before the scores for each subscale could be determined.

Assessment of anxiety

The Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) Scale, recognized for its high validity and reliability, was used to measure the anxiety symptoms present in the enrolled patients. The BAI is a self-report measure with a score range of 0 to 3 and usually consists of 21 items. Thus, the total score for each patient ranges from 0 to 63 points. In this case, patients with higher total scores exhibit more severe anxiety symptoms. Based on our study, anxiety symptoms were categorized as mild if they fell between 8 and 15, moderate if they fell between 16 and 25, and severe if they fell between 26 and 63.

Statistical analyses

The analysis of the data was executed using version 25 of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS). The percentages and frequency distribution of the variables were calculated. Descriptive data were assessed through Fisher's exact test or Chi-square tests. For further analysis, Wilcoxon's test and independent t-test were utilized. A p-value of less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant for each analysis.

Results

Patient characteristics

A screening of 160 postoperative oral cancer patients for study enrollment took place between January 1, 2023, and December 31, 2023. The socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the experimental and control groups are summarized in Table 1. This study included a total of 160 participants; 97 (60.6%, 95% CI: 52.5 – 68.1) of them were male, and 63 (39.4%, 95% CI: 31.8 – 47.4) were female. Significant statistical differences were identified in educational status (p<0.01), occupation (p<0.01), monthly income (p<0.01), and cancer stage (p<0.01).

|

Variables |

Characteristics |

Experimental group (n=80) n (%) |

Control group (n=80) n (%) |

p-value |

|

Age (Years) |

21-30 |

0 |

1 (1.3) |

0.2

|

|

31-40 |

7 (8.8) |

9 (11.3) |

||

|

41-50 |

30 (37.5) |

18 (22.5) |

||

|

51-60 |

23 (28.8) |

25 (31.3) |

||

|

61-70 |

20 (25.0) |

27 (33.8) |

||

|

Gender |

Male |

46 (57.5) |

51 (63.8) |

0.4 |

|

Female |

34 (42.5) |

29 (36.3) |

||

|

Religion |

Hindu |

62 (77.5) |

68 (85.0) |

0.07 |

|

Muslim |

9 (11.3) |

4 (5.0) |

||

|

Christian |

5 (6.3) |

8 (10.0) |

||

|

Others |

4 (5.0) |

0 |

||

|

Educational status |

No formal education |

12 (15.0) |

25 (31.3) |

<0.01*

|

|

Primary |

42 (52.5) |

28 (35.0) |

||

|

Secondary |

26 (32.5) |

21 (26.3) |

||

|

Higher secondary |

0 |

6 (7.5) |

||

|

Graduate and above |

0 |

0 |

||

|

Occupation |

Govt |

2 (2.5) |

0 |

<0.01*

|

|

Private |

9 (11.3) |

5 (6.3) |

||

|

Self employed |

15 (18.8) |

31 (38.8) |

||

|

Daily wager |

17 (21.3) |

23 (28.8) |

||

|

Unemployed |

37 (46.3) |

21 (26.3) |

||

|

Monthly income (Rs) |

≤Rs.10, 000 |

38 (47.5) |

18 (22.5) |

<0.01*

|

|

10, 001-15,000 |

37 (46.3) |

44 (55.0) |

||

|

15, 001-20,000 |

4 (5.0) |

16 (20.0) |

||

|

>20,000 |

1 (1.3) |

2 (2.5) |

||

|

Marital status |

Single |

5 (6.3) |

3 (3.8) |

0.4 |

|

Married |

70 (87.5) |

75 (93.8) |

||

|

Widow |

3 (3.8) |

2 |

||

|

Divorced |

2 (2.5) |

0 |

||

|

Types of surgery |

Tumor Resection |

4 (5.0) |

2 (2.5) |

0.8

|

|

Micrographic surgery |

3 (3.8) |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Glossectomy surgery |

17 (21.3) |

18 (22.5) |

||

|

Mandibulectomy surgery |

40 (50.0) |

44 (55.0) |

||

|

Maxillectomy surgery |

15 (18.8) |

14 (17.5) |

||

|

Neck Dissection |

1 (1.3) |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Cancer Stage |

I |

16 (20.0) |

48 (60.0) |

<0.01*

|

|

II |

24 (30.0) |

20 (25.0) |

||

|

III |

23 (28.8) |

6 (7.5) |

||

|

IV |

17 (21.3) |

6 (7.5) |

||

|

Tumor metastasis |

Yes |

33 (41.3) |

23 (28.8) |

0.1 |

|

No |

47 (58.8) |

57 (71.3) |

||

|

Primary site |

Lip |

6 (7.5) |

4 (5.0) |

0.6 |

|

Buccal Side |

52 (65.0) |

43 (53.8) |

||

|

Hard Palate |

1 (1.3) |

3 (3.8) |

||

|

Posterior molar Region |

2 (2.5) |

3 (3.8) |

||

|

Tongue |

11 (13.8) |

15 (18.8) |

||

|

Floor of mouth |

0 |

2 (2.5) |

||

|

Angle of mouth |

3 (3.8) |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Submandibular gland |

1 (1.3) |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Base of tongue |

3 (3.8) |

3 (3.8) |

||

|

Maxilla |

0 |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Cheek |

0 |

1 (1.3) |

||

|

Alveolus |

1 (1.3) |

3 (3.8) |

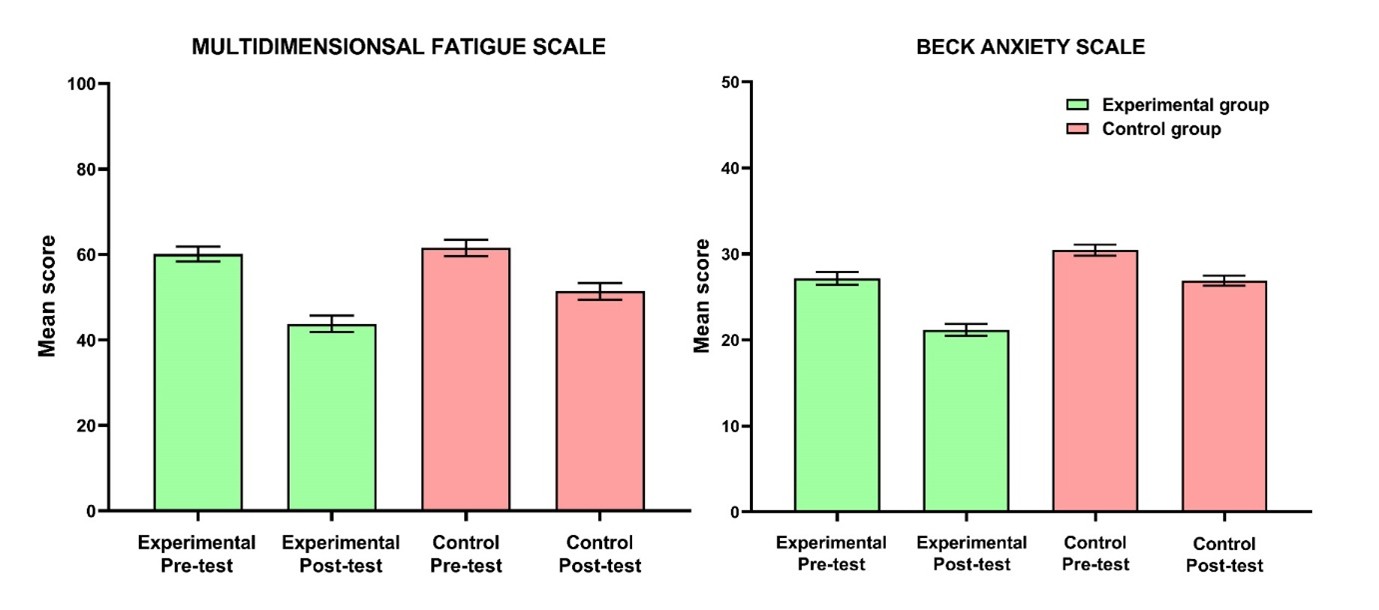

A summary of the descriptive characteristics of pre- and post-test levels of fatigue and anxiety in enrolled patients can be found in Table 2. The Mean and SD of pre-test and post-test levels of fatigue among postoperative patients with oral cancer are illustrated in Table 3. Additionally, Table 4 presents the Mean and SD of pre-test and post-test levels of anxiety among postoperative patients with oral cancer. Figure 2 illustrates that the experimental group achieved a statistically significant reduction in fatigue (p<0.01) and anxiety (p<0.01) following the nursing intervention, as opposed to the control group.

|

Variables |

Characteristics |

Experimental group |

Control group |

||||

|

Pre-test Mean ± SD |

Post-test Mean ± SD |

p-value |

Pre-test Mean ± SD |

Post-test Mean ± SD |

p-value |

||

|

Fatigue |

Mild |

19.0 ± 2.4 |

18.5 ± 2.7 |

0.04*

|

17.5 ± 0.7 |

17.2 ± 2.3 |

0.13

|

|

Moderate |

34.2 ± 3.8 |

33.7 ± 4.2 |

33.2 ± 6.3 |

33.0 ± 6.1 |

|||

|

Severe |

53.5 ± 6.1 |

52.8 ± 5.5 |

50.9 ± 6.2 |

51.1 ± 6.3 |

|||

|

Very Severe |

73.1 ± 5.4 |

72.2 ± 6.2 |

68.5 ± 5.5 |

68.2 ± 5.7 |

|||

|

Exhausted |

82.5 ± 1.5 |

81.0 ± 1.7 |

82.3 ± 2.2 |

82.2 ± 1.8 |

|||

|

Anxiety |

Low |

19.5 ± 3.2 |

19.2 ± 3.8 |

0.10 |

19.1 ± 2.7 |

18.8 ± 3.1 |

0.10 |

|

Moderate |

27.1 ± 4.1 |

26.9 ± 3.5 |

30.1 ± 3.8 |

29.5 ± 3.8 |

|||

|

Potentially concerning the level of anxiety |

38.4 ± 1.8 |

38.0 ± 1.2 |

37.4 ± 1.5 |

37.5 ± 1.9 |

|||

|

Groups |

Domains Of Fatigue |

Max score |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

Wilcoxon’s Test |

|

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Z value |

p-value |

|||

|

Experimental Group (n=80) |

General Fatigue |

20 |

11.7 ± 4.2 |

11.3 ± 3.9 |

-2.6 |

0.03* |

|

Physical Fatigue |

20 |

12.1 ± 4.1 |

12.0 ± 3.7 |

-1.9 |

0.12 |

|

|

Reduced Activity |

20 |

11.1 ± 3.8 |

10.7 ± 3.5 |

-2.4 |

0.04* |

|

|

Reduced Motivation |

20 |

11.8 ± 3.5 |

11.7 ± 4.1 |

-1.3 |

0.20 |

|

|

Mental Fatigue |

20 |

12.5 ± 4.3 |

12.2 ± 4.2 |

-2.7 |

0.05* |

|

|

Overall |

100 |

60.1 ± 15.6 |

58.6 ± 16.1 |

-3.1 |

0.03* |

|

|

Control Group (n=80) |

General Fatigue |

20 |

12.7 ± 4.4 |

12.6 ± 3.9 |

-1.4 |

0.09 |

|

Physical Fatigue |

20 |

12.2 ± 4.1 |

11.8 ± 3.8 |

-2.9 |

0.01* |

|

|

Reduced Activity |

20 |

12.8 ± 3.9 |

12.9 ± 4.2 |

-1.7 |

0.17 |

|

|

Reduced Motivation |

20 |

11.7 ± 3.6 |

11.6 ± 3.7 |

-1.4 |

0.26 |

|

|

Mental Fatigue |

20 |

12.0 ± 3.3 |

11.9 ± 3.8 |

-1.6 |

0.21 |

|

|

Overall |

100 |

61.5 ± 16.4 |

61.2 ± 16.7 |

-1.5 |

0.16 |

|

|

Sl. no. |

Groups |

Max score |

Pre-test |

Post-test |

Wilcoxon’s Test |

|

|

Mean ± SD |

Mean ± SD |

Z value |

p-value |

|||

|

1 |

Experimental Group (n=80) |

63 |

27.2 ± 6.5 |

27.1 ± 6.1 |

-1.2 |

0.16 |

|

2 |

Control Group (n=80) |

63 |

30.4 ± 6.0 |

30.2 ± 6.4 |

-1.3 |

0.28 |

Figure 2. Mean and standard error of mean of fatigue and anxiety scales of experimental and control group.

Discussion

The term head and neck cancers (HNCs) refer to tumors that originate in areas such as the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, nasal cavity, or sinuses. Due to the intricacy of the illness, patients frequently receive intensive multimodal therapy. The location of the tumors and this treatment may have a negative influence on numerous daily functions, including breathing, swallowing, and speaking [13]. According to studies, the most common side effects experienced by people with HNC getting treatment—especially those after surgery—are pain, fatigue, and issues with sleep. For 70% HNC patients, pain is the most prevalent symptom.

With the growing complexity of surgical procedures, patients tend to feel more fatigued, negatively impacting their QOL and increasing the likelihood of developing emotional issues like anxiety and depression. The physical and psychological difficulties that arise after surgery are primarily due to surgical wounds, the stress of the illness, and the nature of the interventions [14]. Patients with oral cancer frequently experience emotional discomfort, fatigue, sleep disturbances, anxiety, and depression. These side effects can develop during therapy and last a long time, making the condition more severe [15].

Following surgery, patients experience problems with their appearance in addition to compromised swallowing, articulation, and chewing abilities. Year by year, surgery is becoming less invasive because of advancements in medical technology, which reduces the physical pain that surgical patients experience afterward. Previous research also indicates that the third day following surgery is a time of change for both mental and physical states and that quality of recovery (QoR) on this day correlates with QOL three months later. Following surgery, QoR is a crucial predictor of postoperative QOL [16]. The QOL is a multidimensional measure of a patient's overall well-being that takes into account their perspective on their physical, social, and emotional functioning areas [17]. An essential component of assessing a patient's psychological state is patient satisfaction. Additionally, financial difficulties, therapy, and communication all had an impact on patients' satisfaction.

There are several screening tools available, with different lengths and levels of complexity. However, before a screening tool can be recommended for routine usage, it must first be shown to be valid in a particular patient population. In our study, we used MFI-20 and BAI, which are two of the most commonly, used questionnaire scales for identifying fatigue and anxiety in oncological settings and are reported as reliable and valid instruments for measuring fatigue [18,19] and anxiety, respectively [20,21]. What the typical symptom pattern is for patients having oral cancer surgery is yet unknown, though. Studies have demonstrated that improved postoperative recovery, one of which centers on stress reduction and symptom relief, can greatly benefit the clinical results of patients with HNC who are having surgery. Hence, by elucidating the primary symptoms and their intensity in surgically treated oral cancer patients, medical professionals could adjust treatment regimens to expedite recovery and enhance clinical results [22]. An earlier study that looked at the correlation between cytokine levels and cancer symptoms found that female patients had higher degrees of fatigue (moderate to severe fatigue) than male patients. Additionally, proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 levels were noticeably higher in those groups [13]. Higher degrees of fatigue are linked to female sex and younger age (<60 years), yet these differences do not persist longitudinally [23].

Through the questionnaire, patients indicated how fatigue and anxiety affected their daily lives and work-related activities in general. The findings of our study indicated that nursing interventions played a crucial role in alleviating postoperative fatigue and anxiety in oral cancer patients, particularly in the experimental group versus the control group. Furthermore, nursing interventions were found to be effective in improving patient knowledge and self-management. For patients with postoperative oral cancer and cancerous pain, the comprehensive nursing intervention method can help them recognize and comprehend their condition, change their perspective, build confidence in their ability to recover, accept and engage with the treatment in a positive manner, reduce the pain and fatigue they feel subjectively, reduce their negative emotions, reduce anxiety, and enhance their QOL and sleep.

Conclusion

There was a significant statistical difference in educational attainment, employment, monthly income, and cancer stage between the experimental and control groups. Post-nursing intervention, the experimental group showed a marked decrease in descriptive characteristics and in the mean and standard deviation of fatigue levels from pre-test to post-test compared to the control group. In contrast, no significant changes were observed in the descriptive characteristics or in the mean and standard deviation of anxiety levels between the two groups.

The QOL for patients undergoing surgery for oral cavity cancer is significantly affected by the treatment, which is the perceived difference between their current state and their ideal expectations. Effective patient outcomes can be achieved by healthcare workers through the use of audio-visual communication, which is very helpful in giving patients personalized and pertinent information while also reducing their psychological burden. Healthcare professionals, including nurses, can employ non-pharmacological strategies such as comprehensive nursing interventions, psychosocial therapies, behavioral or mindfulness-based stress therapies, sleep therapy, physical therapy programs (for instance, exercise, yoga, and massage therapy), and acupuncture, all of which effectively reduce fatigue and anxiety.

Our research presents both advantages and drawbacks. A notable strength is the substantial participation rate. Since only one center was chosen, it's possible that the findings cannot be applied to other demographic groups. Time and money restraints prevented an increase in the sample size. It is recommended that this research be replicated in diverse areas across the country, given that patients' experiences of fatigue and anxiety can differ based on their lifestyle choices and available support. Furthermore, the researchers did not identify any comparable studies conducted in India for reference.

Implication

Implementing these interventions can improve patient fatigue and anxiety, enhance patient QOL, and contribute to better overall healthcare quality. Clinicians and other health professionals can apply the study's inexpensive, time-efficient intervention to their clinical practices. It shouldn't be viewed as a therapeutic substitute, though. The implications identified by the researcher greatly influence nursing practice, administration, education, and research. Through evidence-based, practice-based staff development programs, nurses and other healthcare workers can evaluate their requirements. Workshops, symposiums, and skill labs can be arranged by educational institutions to address postoperative fatigue and anxiety. Nurse administrators should provide funding to uphold acceptable work environments and a happy work environment, in addition to strengthening hospital policies. Generalizing the study's conclusions is made possible by its replication. Publication of the research findings in professional journals and online will help ensure that they are applied as effectively as possible.

Key Message

1). What is current knowledge?

Oral cancer ranks as the second most frequent disease within the Indian population. Postoperative functional impairments are common in patients with oral cancer following surgery. Furthermore, these patients frequently experience fatigue and anxiety, which are strongly linked to a lower QOL.

2). What is new here?

The nursing intervention led to a significant decline in the descriptive characteristics of the experimental group (p<0.04 vs. p=0.13) and in the mean and standard deviation of fatigue levels from pre- to post-test (p<0.03 vs. p=0.16) when compared to the control groups. However, there was no statistically significant change in the descriptive characteristics (p=0.10 for both groups) or in the mean and standard deviation of anxiety levels from pre- to post-test (p=0.16 vs. p=0.28) across the groups.

Source(s) of Support

Nil.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge all the patients who contributed to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' Contributions

Concepts: SN, KF, SD, MP, AD; Design : SN, KF, SD, MP, AD; Definition of intellectual content: SN, KF, SD, MP, AD; Literature search: SN, MP, AD; Clinical studies: AD; Experimental studies: AD; Data acquisition: SN, AD; Data analysis: SN, KF, MP, AD; Statistical analysis: MP; Manuscript preparation: MP, AD; Manuscript editing: SN; Manuscript review: KF, SD. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors, that the requirements for authorship as stated earlier in this document have been met, and that each author believes that the manuscript represents honest work.

Additional Information

Data availability

All data from this study is available with the corresponding author, which will be shared upon request.

Ethics approval statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and this research was approved by Desh Bhagat University’s Institutional Review Board (DBU/RC/2023/2338). The research was conducted at Atal Bihari Vajpayee Regional Cancer Centre, Agartala, Tripura, India.

Patient consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

2. Badwelan M, Muaddi H, Ahmed A, Lee KT, Tran SD. Oral squamous cell carcinoma and concomitant primary tumors, what do we know? A review of the literature. Current Oncology. 2023 Mar 27;30(4):3721-34.

3. Johnson DE, Burtness B, Leemans CR, Lui VW, Bauman JE, Grandis JR. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2020 Nov 26;6(1):92.

4. Chauhan R, Trivedi V, Rani R, Singh U. A study of head and neck cancer patients with reference to tobacco use, gender, and subsite distribution. South Asian journal of cancer. 2022 Jan;11(01):046-51.

5. Nethan ST, Ravi P, Gupta PC. Epidemiology of oral squamous cell carcinoma in Indian scenario. In: Routray S, Editor. Microbes and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A Network spanning infection and inflammation. Singapore: Springer; 2022. P. 1-7.

6. Anwar N, Pervez S, Chundriger Q, Awan S, Moatter T, Ali TS. Oral cancer: Clinicopathological features and associated risk factors in a high risk population presenting to a major tertiary care center in Pakistan. Plos one. 2020 Aug 6; 15(8):e0236359.

7. Berg M, Silander E, Bove M, Johansson L, Nyman J, Hammerlid E. Fatigue in Long-Term Head and Neck Cancer Survivors From Diagnosis Until Five Years After Treatment. Laryngoscope. 2023 Sep;133(9):2211-21.

8. Lundt A, Jentschke E. Long-Term Changes of Symptoms of Anxiety, Depression, and Fatigue in Cancer Patients 6 Months After the End of Yoga Therapy. Integr Cancer Ther. 2019 Jan-Dec;18:1534735418822096.

9. Firmeza MA, de Oliveira PP, Rodrigues AB, da Rocha LC, de Moura Grangeiro AS. Anxiety in patients with malignant neoplasms in the mediate postoperative period: a correlational study. Online Brazilian Journal of Nursing. 2016;15(2):134-45.

10. Yuan L, Pan B, Wang W, Wang L, Zhang X, Gao Y. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms among patients diagnosed with oral cancer in China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2020 Aug 5;20(1):394.

11. Chaitanya NC, Garlapati K, Priyanka DR, Soma S, Suskandla U, Boinepally NH. Assessment of Anxiety and Depression in Oral Muscovites Patients Undergoing Cancer Chemoradiotherapy: A Randomized Cross-sectional Study. Indian J Palliat Care. 2016 Oct-Dec;22(4):446-54.

12. Goedendorp MM, Gielissen MF, Verhagen CA, Peters ME, Bleijenberg G. Severe fatigue and related factors in cancer patients before the initiation of treatment. Br J Cancer. 2008 Nov 4;99(9):1408-14.

13. Sharp L, Watson LJ, Lu L, Harding S, Hurley K, Thomas SJ, et al. Cancer-Related Fatigue in Head and Neck Cancer Survivors: Longitudinal Findings from the Head and Neck 5000 Prospective Clinical Cohort. Cancers (Basel). 2023 Oct 5;15(19):4864.

14. Loh EW, Shih HF, Lin CK, Huang TW. Effect of progressive muscle relaxation on postoperative pain, fatigue, and vital signs in patients with head and neck cancers: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2022 Jul;105(7):2151-7.

15. Gasparro R, Calabria E, Coppola N, Marenzi G, Sammartino G, Aria M, et al. Sleep Disorders and Psychological Profile in Oral Cancer Survivors: A Case-Control Clinical Study. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr 13;13(8):1855.

16. Araya K, Fukuda M, Mihara T, Goto T, Akase T. Association Between Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms During Prehospitalization Waiting Period and Quality of Recovery at Postoperative Day 3 in Perioperative Cancer Patients. J Perianesth Nurs. 2022 Oct;37(5):654-61.

17. Palitzika D, Tilaveridis I, Lavdaniti M, Vahtsevanos K, Kosintzi A, Antoniades K. Quality of Life in Patients With Tongue Cancer After Surgical Treatment: A 12-Month Prospective Study. Cureus. 2022 Feb 23;14(2):e22511.

18. Wondie Y, Hinz A. Application of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory to Ethiopian Cancer Patients. Front Psychol. 2021 Dec 2;12:687994.

19. Bakalidou D, Krommydas G, Abdimioti T, Theodorou P, Doskas T, Fillopoulos E. The Dimensionality of the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI-20) Derived From Healthy Adults and Patient Subpopulations: A Challenge for Clinicians. Cureus. 2022 Jun 26;14(6):e26344.

20. Garcia JM, Gallagher MW, O'Bryant SE, Medina LD. Differential item functioning of the Beck Anxiety Inventory in a rural, multi-ethnic cohort. J Affect Disord. 2021 Oct 1;293:36-42.

21. Starosta AJ, LA B. Beck anxiety inventory. Encyclopedia of clinical neuropsychology. Cham: Springer. 2017.

22. Ou M, Wang G, Yan Y, Chen H, Xu X. Perioperative symptom burden and its influencing factors in patients with oral cancer: A longitudinal study. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2022 Aug 1;9(8):100073.

23. Abel E, Silander E, Nordström F, Olsson C, Brodin NP, Nyman J, et al. Fatigue in Patients With Head and Neck Cancer Treated With Radiation Therapy: A Prospective Study of Patient-Reported Outcomes and Their Association With Radiation Dose to the Cerebellum. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2022 Apr 8;7(5):100960.