Abstract

Different computational models and new devices are under development, aiming to better comprehend and alter brain function. Ternary computating offers new approach by considering a third physiological state of the neuronal membrane: the refractory period (-1), in addition to resting potential state (0) and the action potential (1). As implants and trustworthy maps of the brain become more sophisticated due to a revolution in material science, new therapies emerge, with potential to treat chronic and often hard to treat neurological issues, but the ethical and economic issues regarding these advances still need debating, as well as more studies.

Keywords

Brain computation, Ternary computation, Brain implants, Brain-machine interfaces, Neural stem cell, Deep brain stimulation, Parkinson’s Disease, Alzheimer’s Disease, Bioelectronics, Neuron wiring

Abbreviations

DBS: Deep Brain Stimulation; BMI: Brain-machine Interface; CRISPR: Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats

Introduction

It is common knowledge that the neuron uses two types of computation: analogic and digital. The analogic computation happens at the dendritic area, where the summation of coming impulses must reach a threshold to shoot an irreversible electrical impulse, the action potential, which consists of an inversion of the membrane electrical potential [1]. The signal then runs along the axon in a unidirectional spike (digital computation). This mechanism enables the organisms to rapidly transport information inside the body and is therefore essential for complex lifeforms.

Since the action potential is either present, 1, or absent, 0, it seemed easy to assume binary computation as the most accurate way to model the brain. That is not a consent though.

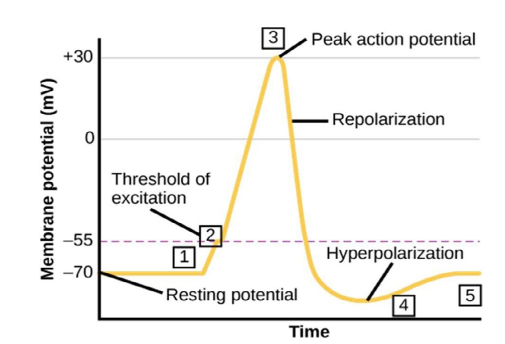

A different model for brain computation, a ternary one, has been proposed by several authors [2]. It considers a third distinct physiological state of the neuronal membrane: the refractory period, -1. During the resting state, the membrane potential is about -70 mV. If the summation of the impulses coming from other neurons reaches -55 mV, the neuron will fire an action potential, followed by a depolarization. The cell then enters a state of repolarization and consecutive hyperpolarization, which renders the neuronal membrane potential even more negative, farther from the threshold. While in this condition additional stimulus is necessary to reach the adequate membrane potential and fire an action potential (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The action potential: (1) Stimulus from a sensory cell or another neuron. (2) The threshold of excitation is reached, all Na+ channels open and the membrane depolarizes. (3) Peak of action potential: K+ channels open and K+ begins to leave the cell. At the same time, Na+ channels close. (4) The membrane becomes hyperpolarized as K+ ions continue to leave the cell. The hyperpolarized membrane is in a refractory period and cannot fire. (5) The K+ channels close and the Na+/K+ transporter restores the resting potential (figure modified under the licence CC BY 3,0 [1]).

The acknowledgment of the refractory period is the differential of ternary computation. It considers the amount of time it takes for an excitable membrane to be ready for a second stimulus. The absolute refractory period corresponds to depolarization and repolarization, whereas the relative refractory period corresponds to hyperpolarization. During the refractory period, if there is a stimulus, or if a spike converges to this point of the circuitry, an action potential will not be generated [1]. In consequence, the duration of the refractory period inversely affects the frequency pattern of spikes in the neuron.

Because of these interactions, it is interesting to consider the ternary computational model as default for brain computation. A trustworthy model could improve mapping, information decoding and simulation of the human brain circuitry, often hard to study in vivo. Besides, the brain has large computational capacity and consumes less energy (the equivalent of a light bulb of 20 W) than traditional computers [3,4]. The brain architecture and functionality serve therefore as inspiration: mimicking cerebral processes with electronic devices and silico models, and with them creating neuromorphic devices, new and more efficient ways of computing can be created, and studies of the brain with intimacy not previously known would be feasible, now without the restraints of an in vivo model. The rise of new technologies born out of this field of research, may also improve the quality and availability (model/design) of brain or neural implants.

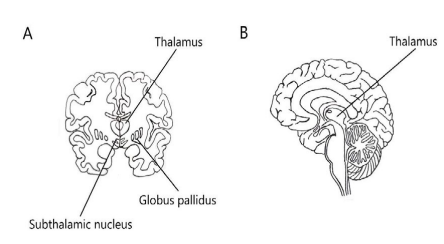

These devices are often portraited in futuristic science fiction, enabling people to directly plug into the network or generate new abilities and senses [3-5], but some of them are a reality already. Cochlear implants, since 1957, transform sound into electric signals and directly stimulate the auditory nerve [6]. Some patients with Parkinson’s disease benefit from implanted electrodes, which fire electrical impulses into specific frequencies. This technology, called deep brain stimulation (DBS), modulates the abnormal activity that causes symptoms, improving the patient’s quality of life through a decrease of tremors and rigidity [7]. The results of this implant are similar to that of Levodopa, but without the symptoms’ fluctuations and drug side effects. DBS triggers blood flow and chemical reactions which lead to the release of neurotransmitters. It acts as a pacemaker, providing regular sets of electrical adjustable impulses (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sketches. Coronal section of the brain (A). Sagittal section of the right brain hemisphere (B). Three areas in the brain are the target for electric stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: subthalamic nucleus, the globus pallidus, and the thalamus (ventral intermediate nucleus) [14-17].

In 2013, a 52 years old patient had a brain-machine interface (BMI) surgically implanted, in order to provide movement capacity lost because of tetraplegia. After the surgery and 13 weeks of training, the participant was able to move the prosthetic limb, and accomplished high-performance seven-dimensional movement [8]. BMIs have also been used in communication. In a recent research, a patient accurately and independently controlled a computer typing program 28 weeks after implanting a BMI and was then able to type two letters per minute. The BMI supplemented and even supplanted the patient's eye-tracking device [9].

And the perspectives for BMIs? Neuralink, one in many multidisciplinary groups with focus on neurosciences [10], might have an answer: it foresees the possibility of a full integrated BMI. The purpose of that would be the achievement of a sort of symbiosis with artificial intelligence (AI). In a scenario where AI mightily surpasses human intelligence, a fusion with an adjuvant supplemental circuitry could be a way to keep us up with the deep transformations caused by intelligent machines [11]. Neuralink may be one small step ahead in that direction, and according to the company, the focus keeps on patient safety.

Simply put, they hypothesize the brain as limbic system (responsible for emotions) and cortex (the thinking part of the brain). Smartphones and computers would represent a third and digital layer yet limited by our sensory and motor abilities. Neuralink implants intend to increase the speed of connection between brain and digital pieces and improve present bandwidth, with attention to output [11]. This raises several ethical, social and economic questions, which should be deeply discussed by scientists, politicians and the community [12,13]. After all, technology reverberates the ideas of the society in which it is developed, for good or bad.

The initial goal of Neuralink is to understand and treat brain or spine related disorders, empowering disabled patients to control phones and computers through use of implanted devices. By reading, decoding and stimulating neuronal spikes, Neuralink’s electrodes would enable these patients to control their electronic devices. With an order of 10 electrodes, Parkinson’s DBS is one of the best U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved systems [14-16]. Neuralink implants have up to 10,000 electrodes. Since neurons represent information by the timing of spikes [1,17], Neuralink implants, with their superior capacity of information conduction, should be able to both record and stimulate neurons, reading and converting analogic and digital signals. Developers admit, though, that implant capacity is limited by the properties of the available materials.

Human trials with Neuralink implants are supposed to initiate in 2020 and will involve severely paralysed patients. The goal is to capacitate them to operate phones and computers. The company says the procedure will be as easy and safe as Lasik, a simple laser surgery with duration of about 15 minutes [18-21]. It could, in the future, become an elective procedure available to people in need of it.

We’ve been discussing the insertion of electronics in the nervous system, but we should also consider the possibility of mixed implants [22], made of electronic and biological parts. These components could carry molecules, drugs, growth factors and even living cells [23-26], that could be derived from stem cell technology, a tool with ever growing importance in regenerative medicine [27,28]. Previous research demonstrates that probes coated with gelatin can improve neuronal density and reduce microglial pro-inflammatory responses [29]. The biomaterial component of these hybrid implants could act as a modulator of immune response, angiogenesis and cellular environment, through the transport of molecules and cells.

The ideal biomaterial for implants or their coating should be biocompatible and antimicrobial. Nevertheless, stimulus of the natural physiology of the host tissue would be also desirable. Oxides, for instance, can be used to create a film around metallic implants and facilitate integration with host tissue [30,31]. Titanium is the most biocompatible metal because it is corrosion resistant, bio-inert, capable of osseointegration and endures intense stress. In the presence of oxygen, it naturally forms a protective oxide film. This thin layer prevents reactions between the metal and the harsh surrounding environment, and even though there are reports of pathogenic metal eating bacteria [32-34], there is no evidence of such in titanium, rendering it safe for implants.

Living cells are another form of biomaterials. Stem cells, specially, would offer advantages, for they can be differentiated in many cell types, from allogeneic or endogenous sources. Endogenous cells, obtained from the patient, enable production of immune-compatible neuron-like cells [35]. Should cells with different genetic material be needed, the source for them could be either allogeneic or modified endogenous cells. These could be obtained through gene editing technology, such as CRISPR [36,37]. Thus, stem cell development could provide a variety of nervous cells. Neurons are the main goal. That because neuron synapses allow the nervous system to interpret and change receiving information, so it works basically as a chip: the neural chip. Each neuron has about 10,000 synapses, in a brain with about 100 billion neurons [17], totalizing 1 quadrillion neuronal connection.

Therefore, cells could be an aid for implants. Other way around is glimpsed as well: implants could become some sort of support for cell therapy, based on the saying “fire together, wire together” [38]. Implants could facilitate integration of newly transplanted neurons with the rest of the nervous system, assuring graft survival as well, an issue in stem cell technology field [39]. All that through electric orchestration.

An example of that lies in Alzheimer’s disease. One consequence of it is synaptic loss, which in turn causes neuronal exclusion from the neural grid and culminates in the death of the cell. Even though neuroinflammation appears to be the main issue to be tackled in Alzheimer’s disease [40-42], implants could help to stimulate neuron firing and to maintain integration to the neural circuitry or facilitate newly transplanted neurons to integrate as well.

If stimulation turns out to be effective in neuron integration, it would immensely help cell therapy and tissue transplants [43]. In cases where timing is essential, as in vision related issues, there is a short time window during brain maturation to learn to see and interpret visual stimuli. After 7 years old, neuroplasticity is usually reduced and treatments for the visual system are less effective [44].

That happens because the neuronal maturation and integration depends on usage of action potentials in specific frequencies during its development. It is through them that the system can coordinate the cellular integration to the circuitry. Genetic expression can be used to label neuron-like cells, but it is the ability to fire action potentials and create new synapses (neuroplasticity [45]) that give the neuron the tools needed to fulfil its function. The electric properties of neuronal maturation are being recorded and mapped. This data could bring better understanding of this process and help simulate artificial electric patterns and evaluate its effects in regenerative strategies [46]. This artificially generated stimulus could accelerate electrophysiological maturation of stem cell derived neurons, both in vitro and in vivo, and help their integration grafts, as well as retard the cognitive loss in elderly through a boost in neuroplasticity.

In the wake of what is being considered the fourth industrial revolution, the biomedical sciences are going to play a bigger role than in any previous moment of human history [12]. The line that separates organic and synthetic is to become ever thinner, with the advent an array of new biocompatible components, and more efficient insulators and superconductors [22]. The biological field progresses in a pace never seen, thanks to the development in stem cell research, bioengineering, gene editing, optogenetics and data science. These, combined to emerging forms of computation, are about to bring even more disruption [13], and restorative neuroscience is a field to be benefited from this revolution. Research is still needed. Severely disabled patients could have their locomotion, movement and sensitivity ameliorated and be given back their independence. Humanity has benefited from technology and must continue to improve it. That said, it is important to consider the challenges of this new era. The economic gap between more and less favoured grows bigger, and creates difficulty in the distribution of these advances, and a cruel and unfair a health gap could be even more expanded as well. The communication revolution, largely responsible for the exchange of information that led to the scientific and cultural upheaval experienced today, may also be a hindrance: privacy and data safety have never been more at risk, and the individual biological information must be protected and cared for at all costs [47,48].

It is easy to get carried away by all the possible advancements and enhancing of abilities that are about to take place. But it is important to consider these delicate questions and push through them with the ethical treatment of the subjects, their safety and wellbeing, and consider the potential to a more egalitarian distribution of our resources and knowledge.

References

2. Johnson AS, Winlow W. Are Neural Transactions in the Retina Performed by Phase Ternary Computation? Annanlsnof Behavioral Neuroscience.2019;2(1):223–36.

3. Merkle RC. Energy limits to the computational power of the human brain. Foresight Update. 1989 Aug;6.

4. Drubach DMD. The Brain Explained. Pearson; 2000. 176 p.

5. Reynolds A. Great Wall of Mars. In: Beyond the Aquila Rift : The Best of Alastair Reynolds ( English Edition ). Gollancz, editor. London: Gollancz; 2016. 784 p.

6. Santina CD (Jonhs HM. Introduction to Cochlear Implantation: Johns Hopkins Listening Center | Q&A [Internet]. Introduction to Cochlear Implantation: Johns Hopkins Listening Center | Q&A. Baltimore, USA: Johns Hopkins Medicine; 2017. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wYUd24x248

7. Michigan Medicine. Deep Brain Stimulation at Michigan Medicine [Internet]. USA: Movement Disorders Clinic at Michigan Medicine; 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3pSMFYhh5E8

8. Collinger JL, Wodlinger B, Downey JE, Wang W, Tyler-Kabara EC, Weber DJ, McMorland AJ, Velliste M, Boninger ML, Schwartz AB. High-performance neuroprosthetic control by an individual with tetraplegia. The Lancet. 2013 Feb 16;381(9866):557-64.

9. Vansteensel MJ, Pels EG, Bleichner MG, Branco MP, Denison T, Freudenburg ZV, Gosselaar P, Leinders S, Ottens TH, Van Den Boom MA, Van Rijen PC. Fully implanted brain–computer interface in a locked-in patient with ALS. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016 Nov 24;375(21):2060-6.

10. Jun JJ, Steinmetz NA, Siegle JH, Denman DJ, Bauza M, Barbarits B, Lee AK, Anastassiou CA, Andrei A, Aydın Ç, Barbic M. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature. 2017 Nov;551(7679):232.

11. Neuralink. Neuralink Launch Event USA: YouTube; 2019. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r-vbh3t7WVI

12. Yoon D. What we need to prepare for the fourth industrial revolution. Healthcare informatics research. 2017 Apr 1;23(2):75-6.

13. Schwab K. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. 1st ed. Currency; 2017. 189 p.

14. Mirzadeh Z, Chapple K, Lambert M, Evidente VG, Mahant P, Ospina MC, Samanta J, Moguel-Cobos G, Salins N, Lieberman A, Tröster AI. Parkinson’s disease outcomes after intraoperative CT-guided “asleep” deep brain stimulation in the globus pallidus internus. Journal of neurosurgery. 2016 Apr 1;124(4):902-7.

15. Benabid AL, Chabardes S, Mitrofanis J, Pollak P. Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. The Lancet Neurology. 2009 Jan 1;8(1):67-81.

16. Mitchell KT, Larson P, Starr PA, Okun MS, Wharen Jr RE, Uitti RJ, Guthrie BL, Peichel D, Pahwa R, Walker HC, Foote K. Benefits and risks of unilateral and bilateral ventral intermediate nucleus deep brain stimulation for axial essential tremor symptoms. Parkinsonism & related disorders. 2019 Mar 1;60:126-32.

17. Lent R. Cem Bilhões de Neurônios? Conceitos Fundamentais de Neurociências. 2nd ed. Atheneu. 2009.

18. Medical MN. Laser Eye Surgery (LASIK) by Nucleus Medical Media. YouTube; Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-YkzgfgN2k

19. Patel DB, Patel AM, Shah MA, Vyas AK, Shah S. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction following LASIK surgery. Indian Journal of Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 2018 Oct;4(4):473-7.

20. Chan TC, Ng AL, Cheng GP, Wang Z, Ye C, Woo VC, Tham CC, Jhanji V. Vector analysis of astigmatic correction after small-incision lenticule extraction and femtosecond-assisted LASIK for low to moderate myopic astigmatism. British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2016 Apr 1;100(4):553-9.

21. Kohnen T, Lwowski C, Hemkeppler E, Petermann K, Forster R, Herzog M, Böhm M. Comparison of Femto-LASIK with combined Accelerated Crosslinking to Femto-LASIK in high myopic eyes: a prospective randomized trial. American journal of ophthalmology. 2019 Nov 1.

22. Simon DT, Gabrielsson EO, Tybrandt K, Berggren M. Organic bioelectronics: bridging the signaling gap between biology and technology. Chemical Reviews. 2016 Jul 1;116(21):13009-41.

23. Yamada A, Vignes M, Bureau C, Mamane A, Venzac B, Descroix S, Viovy JL, Villard C, Peyrin JM, Malaquin L. In-mold patterning and actionable axo-somatic compartmentalization for on-chip neuron culture. Lab on a Chip. 2016;16(11):2059-68.

24. Carvalho BF de, Sousa DB de C, Portela Neto AJ, Nunes JPS, Vasconcelos PAS de. Medicinal properties of amniotic stem cells. JBRA Assistance Reproduction. 2013;17(5):1–4.

25. Spencer KC, Sy JC, Ramadi KB, Graybiel AM, Langer R, Cima MJ. Characterization of mechanically matched hydrogel coatings to improve the biocompatibility of neural implants. Scientific reports. 2017 May 16;7(1):1952.

26. Ryu S, Lee SH, Kim SU, Yoon BW. Human neural stem cells promote proliferation of endogenous neural stem cells and enhance angiogenesis in ischemic rat brain. Neural regeneration research. 2016 Feb;11(2):298.

27. de Carvalho BF, de Souza Sene I, de Carvalho AL, de Vasconcelos PA. The current need to continue researching with embryonic stem cell. JBRA Assisted Reproduction. 2013 Feb 1;17(1):53-5.

28. Evangelista LS, Devina F, Carvalho BF. The Stem Cell Research and the Aging of Brazilian Population. JBRA assisted reproduction. 2015 Jan 1;19(1):33-5.

29. Köhler P, Wolff A, Ejserholm F, Wallman L, Schouenborg J, Linsmeier CE. Influence of probe flexibility and gelatin embedding on neuronal density and glial responses to brain implants. PLoS One. 2015 Mar 19;10(3):e0119340.

30. Kim SE, Lim JH, Lee SC, Nam SC, Kang HG, Choi J. Anodically nanostructured titanium oxides for implant applications. Electrochimica Acta. 2008 May 30;53(14):4846-51.

31. Veronesi F, Giavaresi G, Fini M, Longo G, Ioannidu CA, d'Abusco AS, Superti F, Panzini G, Misiano C, Palattella A, Selleri P. Osseointegration is improved by coating titanium implants with a nanostructured thin film with titanium carbide and titanium oxides clustered around graphitic carbon. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 2017 Jan 1;70:264-71.

32. Sánchez-Porro C, de la Haba RR, Cruz-Hernández N, González JM, Reyes-Guirao C, Navarro-Sampedro L, et al. Draft genome of the marine gammaproteobacterium Halomonas titanicae. Genome Announcments [Internet]. 2013;1(2):1–2.

33. Von Graevenitz A, Bowman J, Del Notaro C, Ritzler M. Human infection with halomonas venusta following fish bite. Journal of Clinical Microbiology.2000;38(8):3123–4.

34. Stevens DA, Hamilton JR, Johnson N, Kim KK, Lee JS. Halomonas, a newly recognized human pathogen causing infections and contamination in a dialysis center: Three new species. Medicine (Baltimore).2009;88(4):244–9.

35. Persoon CM, Moro A, Nassal JP, Farina M, Broeke JH, Arora S, Dominguez N, van Weering JR, Toonen RF, Verhage M. Pool size estimations for dense‐core vesicles in mammalian CNS neurons. The EMBO journal. 2018 Oct 15;37(20).

36. Ran FA, Hsu PD, Wright J, Agarwala V, Scott DA, Zhang F. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nature protocols. 2013 Nov;8(11):2281.

37. Kalebic N, Taverna E, Tavano S, Wong FK, Suchold D, Winkler S, Huttner WB, Sarov M. CRISPR/Cas9‐induced disruption of gene expression in mouse embryonic brain and single neural stem cells in vivo. EMBO reports. 2016 Mar 1;17(3):338-48.

38. Rose T, Hübener M. Neurobiology: Synapses get together for vision. Nature. 2017 Jul;547(7664):408.

39. Uemura M, Refaat MM, Shinoyama M, Hayashi H, Hashimoto N, Takahashi J. Matrigel supports survival and neuronal differentiation of grafted embryonic stem cell-derived neural precursor cells. Journal Neuroscience Research. 2010;88(3):542–51.

40. Mayeux R, Stern Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine. 2012 Aug 1;2(8):a006239.

41. Chen JH, Ke KF, Lu JH, Qiu YH, Peng YP. Protection of TGF-β1 against neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration in Aβ1-42-induced alzheimer’s disease model rats. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):1–19.

42. Zhang J, Ke KF, Liu Z, Qiu YH, Peng YP. Th17 Cell-Mediated Neuroinflammation Is Involved in Neurodegeneration of Aβ1-42-Induced Alzheimer’s Disease Model Rats. PLoS One. 2013;8(10).

43. Garzón-Muvdi T, Quiñones-Hinojosa A. Neural stem cell niches and homing: recruitment and integration into functional tissues. Ilar Journal. 2010 Jan 1;51(1):3-23.

44. Holmes JM, Levi DM. Treatment of amblyopia as a function of age. Visual neuroscience. 2018;35.

45. Cramer SC, Sur M, Dobkin BH, O'brien C, Sanger TD, Trojanowski JQ, Rumsey JM, Hicks R, Cameron J, Chen D, Chen WG. Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain. 2011 Apr 9;134(6):1591-609.

46. Telias M, Segal M, Ben-Yosef D. Electrical maturation of neurons derived from human embryonic stem cells. F1000Research. 2014;3.

47. Elhai JD, Frueh BC. Security of electronic mental health communication and record-keeping in the digital age. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2016 Feb 1;77(2):262-8.

48. Abouelmehdi K, Beni-Hessane A, Khaloufi H. Big healthcare data: preserving security and privacy. Journal of Big Data. 2018 Dec 1;5(1):1.