Abstract

Evolution of our thinking and design of cancer therapeutics [1] has gone through a tortuous path in the last eighty or so years, since the first patient was treated with a chemical agent [2]. Introduction of nitrogen mustard in the treatment of cancer in 1940’s was based on a serendipitous finding and observation during the second world war [3].

Design of multiagent chemotherapy protocols [4] which was the next step in the evolution of this path, was based on the thinking that killing cancer cells through interference with their life cycle in multiple directions and through multiple paths, would lead to a better outcome.

Through time, dissection of different intracellular pathways [5], related to cell survival and proliferation, has guided the design of newer agents interfering with and antagonizing those pathways [6]. The driving force of our thinking has all time been development of more sophisticated means to kill cancer cells [7].

Recurrence of cancer following complete response, as well as upfront resistance to chemo and targeted therapy has led to significant frustration and roadblock in clinical arena [8]. This has led to consideration of other kinds of approach to neoplastic disorders.

Meanwhile a better understanding of fundamental concepts, such as chromosomal instability [9] and intratumor heterogeneity [10], alongside developments, such as single cell sequencing [11] and nano-technology [12] have started to pave the road for future cancer therapeutics.

Keywords

Entropy, Master regulator complex, Cellular network entropy, Nano-machines, Cancer tumor evolutions, Future cancer therapeutics

Introduction

The second law of thermodynamics [13] has rightfully been recognized as the most fundamental law that prevails the known universe [14]. Interplay of living cell with this law is perhaps the most fascinating of all [15]. The most elegant part of this interplay is to maintain the network entropy [16] of numerous subcompartments of living cell at the lowest possible level, dictated by the limits of the second law. This inversely correlates with the maximum amount of free energy in different subcompartments of the living cell [17]. During the lifetime of living organisms, there is a constant tug of war, which at one end drags the cell towards higher level of entropy through the spontaneous increase in entropy of the surrounding universe, and a pullback by the constituents of living cell to lowest possible level, at the other end.

As such, since inception of life in primordial oceans [18], living organisms have armed themselves with sensors [19] in virtually every corner, angle and subcompartment, and executors which work in harmony to maximize free energy which inversely correlates with network entropy [20]. Indeed, this is the foundation of living organisms and the engine of their evolution in the last thirty-eight hundred million years or so.

One could see such footprints/sensors and executors across the board and without exception, ranging from telomeres [21] to epigenome [22], micro-RNA network [23], gene regulatory mechanisms [24] and protein-protein interactions [25]. Forward move of the thermodynamic arrow of time gradually shifts the equation towards higher level of systems network entropy [26].

Among a multitude of DNA damaging agents [27], inflammation seems to be the strongest pro-entropy force carrying the most immediate destructive power [28]. That is why our cells at mid-life are loaded with diverse group of mutations, the goal of which is protection against this strong pro-entropy force [29]. However, during the latter part of our life, as a result of universal increase in systems network entropy, those protective mutations prove deleterious.

Consequently, it makes a lot of sense that our future cancer therapeutics would tackle this most fundamental issue.

Entropy and Living Cell

The second law of thermodynamics is sitting at the center of evolution of life on earth. By the virtue of this law, the index of instability or disorder of the known universe is incessantly on the rise. This correlates inversely with free energy of a closed thermodynamic system. It has long been recognized that the living cell is the most efficient machinery as far as capability to minimize the speed of rise in entropy is concerned. All the subcompartments of living cell have evolved and have been selected toward achievement of this goal. This ranges from quaternary structure of cellular proteins [30], to elasticity of cell membrane [31], regulatory gene mechanisms [32], RNA spliceosomes [33], micro-RNA network [34], and epigenome [35].

Cellular networks, ranging from G-protein coupled receptors [36] which act as the radar of cellular energetics, modulating fair and balanced distribution of cellular energy, to proteasomes [37] and ubiquitination machinery [38] which eliminate old proteins characterized by their distorted quaternary structures which portend significant decrease in their plasticity or free energy, follow the same law. This further extends to fine harmony and alignment of constituents of Krebs cycle [39] and ATP generating machinery of mitochondrion [40].

Mitotic spindles [41], microtubules [42], kinetochores [43], centromere geometry [44] and centrosomes [45], as well as telomeres [46] are not exceptions to this rule. Indeed, the fine orchestration and spontaneity of sequence of complex events are all different notes of this fascinating symphony of life.

I have alluded to this process as law of spontaneity in the book that I published in 2018 [47]. The two major components of this fascinating harmony are sensors [48], which exist at virtually any subcompartment of the cell and executors [49], which have evolved to adopt the task of keeping cellular networks entropy at the lowest level, as per the limits of the second law of thermodynamics. Perhaps the most important of these sensors are the ones that sense thermodynamics arrow of time [50], which directly lead to aging [51] and increase in cellular network entropy.

Telomeres could be considered the masterpiece built into the genome in this regard [52]. Their shortening following consecutive rounds of mitosis reflects the passage of time [53], which at a critical threshold activates apoptotic machinery to prevent catastrophic cellular events [54].

As perfect a machinery as living cell is, clearly it cannot escape minimal increase in network entropy [55], the accrual of which through time, leads to aging [56], disease [57], and demise [58]. In this regard, neoplastic transformation [59] could be considered a process in which increase in cellular networks entropy happens at a massively fast pace [17], such that the built-in cellular machineries cannot catch up with its repair, even if they have remained functional. Clearly sensors, executors, or a combination of both could have become dysfunctional in different scenarios and to different degrees.

Methodology

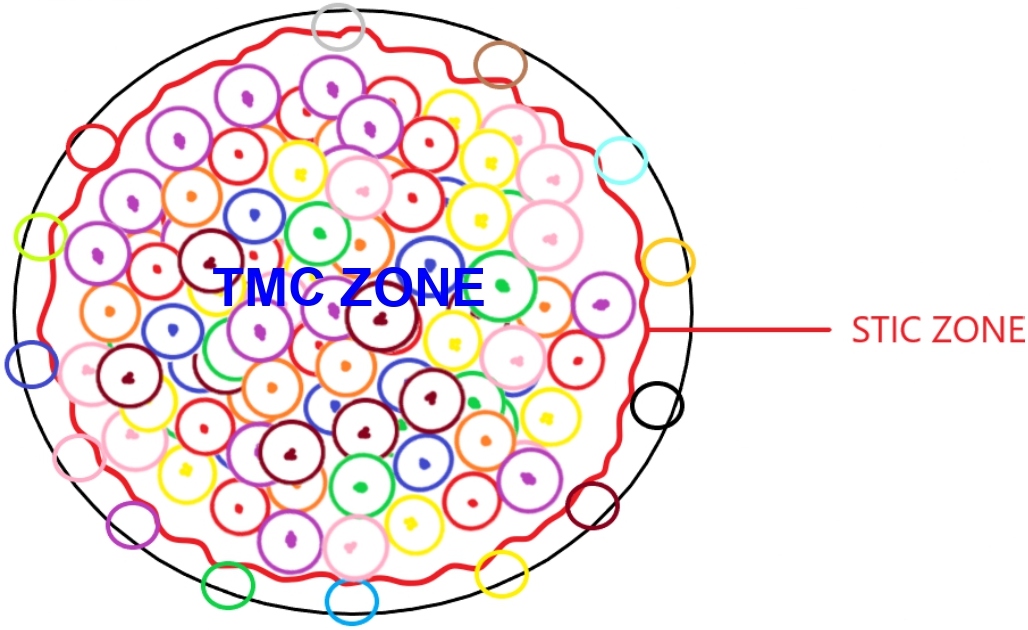

By employing single cell sequencing technology, we could derive and decipher DNA, RNA, micro-RNA, epigenome, and protein signatures of master regulator clusters of cells in game changing compartments of tumor mass [60]. In this regard, glioblastoma multiforme could serve as a reasonable example [61] (Figure 1).

Figure 1: General schema of glioblastoma multiforme tumor mass with TMC and STIC zone representations.

TMC zone (Tumor Mass cell zone) generates tumor bulk, by replication and generation of pre-existing and new gene signatures. STIC zone (Stem-like tumor initiating cell zone) homes the stem like initiating cancer cells. Cells in this zone could reprogram tumor mass following surgical resection, by a multitude of mechanisms, including conversion to tumor mass zone cells.

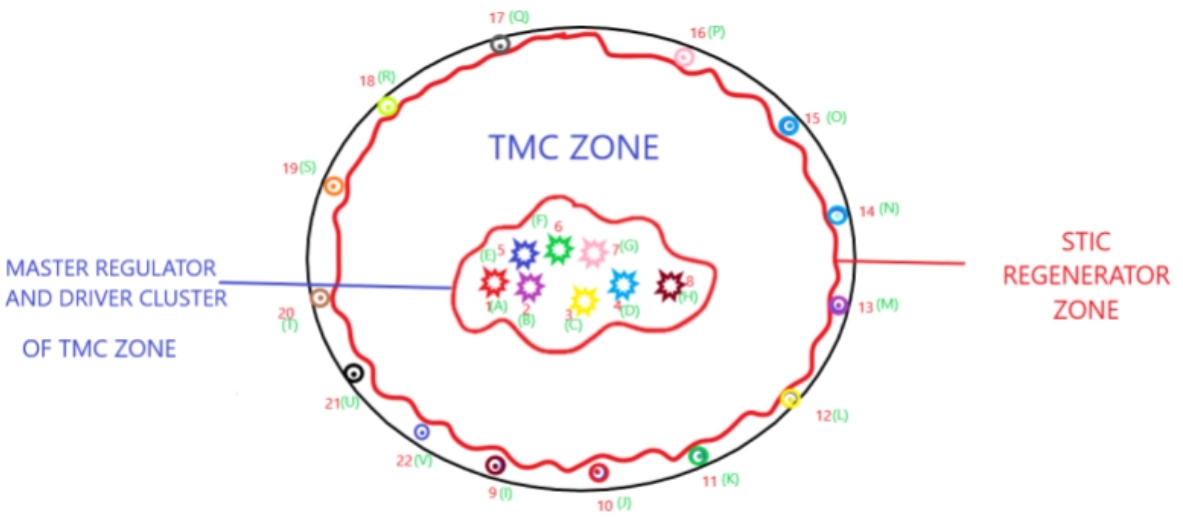

Cluster of master regulator and driver cells reside in TMC (tumor mass cell) zone, and regenerator cells exist in STIC (stem-like initiating cell) zone [62]. Master regulator and driver cluster of cells in TMC (tumor mass cell) zone act as a driving force for repopulating the tumor mass. Regenerator cells could replenish the whole glioblastoma multiforme tumor mass with their diverse group of DNA, RNA, protein, and epigenome signatures following surgical resection [63] (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Master regulator complex network entropy. A-H: different values of master regulator complex network entropy and single cell sequenced DNA & RNA signatures; 1-8: hold master regulator network entropy values and their signatures of A-H; 9-22: STIC (stem-like initiating cell) regenerator cells, hold master regulator network entropy values and their signatures of I-V.

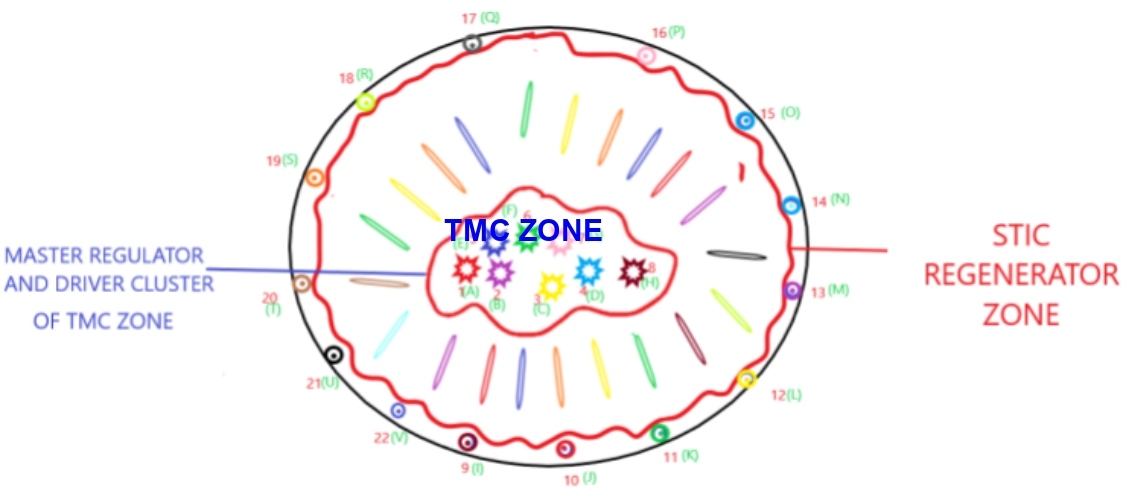

Following single cell sequencing and measurement of master regulator complex network entropy and genetic signature of malignant cells in these two key areas of tumor mass and deciphering their evolutionary roadmap, programmable nano-machines would get deployed to execute appropriate modifications of their cellular and master regulator complex network entropy and distorted signatures [64] (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Master regulator complex network entropy and distorted signatures. TMC zone: Tumor Mass Cell Zone; STIC zone: Stem-like Initiating Cell Zone.

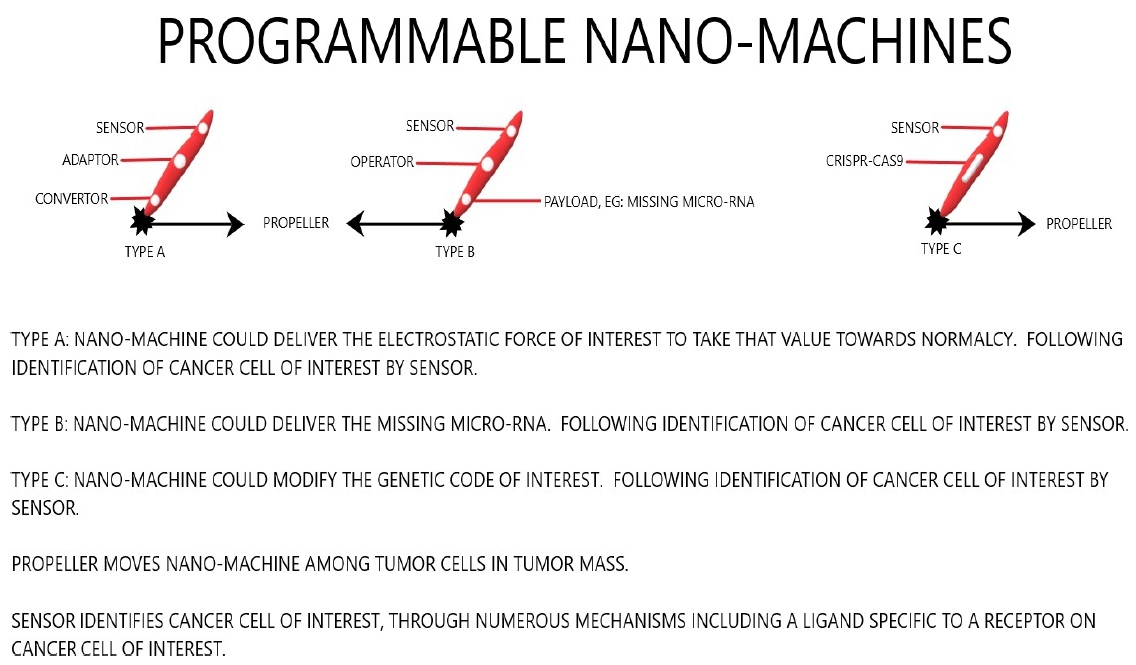

Depiction of programmable nano-machines deployed into tumor mass to execute the task of appropriate modification of master regulator network entropy and gene signatures. There are so many different ways to achieve this goal and this needs to get tailored and customized for different malignancies, in different ways. In case of glioblastoma multiforme, programmable nano-machines could get delivered intraoperatively or following surgical resection by painting the resection margins with a liquid containing the programmable nano machines. Generally speaking, programmable nano-machines, which are capable of modifying the master regulator complex network entropy and other distortions, could either get delivered intralesionally or systemically.

Such conversion could be done either by delivering the calculated electrostatic forces into the cells in the areas of interest [65], or by delivering the necessary modifications in genome, epigenome, protein, RNA, or micro-RNA compartments [66] (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Programmable nano-machines.

As such, we would be tackling the heart of the matter, namely distorted cellular and master regulator complex network entropy, which is sitting at the center of neoplastic transformation. Consequently, evolutionary road of tumor mass would get blocked or slowed down. This eventually leads to significant prolongation of patient’s life, and on occasion could potentially translate into cure.

Conclusion

The last eighty or so years has been quite a fascinating journey in the history of cancer therapeutics. We started with nitrogen mustard and evolved into multi-agent chemotherapy, targeted [67] and immunotherapy [68]. We have developed multimodality treatment strategies, combining surgical resection, chemo and radiation therapy.

As technology and knowledge in cancer biology have evolved, we also have continued to evolve our cancer therapeutics. However, our metastatic cancer patients for the most part have remained incurable.

The time has come for addressing the most fundamental principle that is sitting at the heart of neoplastic transformation, namely distorted cellular and master regulator complex network entropy of malignant cell, and push these abnormal states towards normalcy. We need to change our path of thinking and cancer treatment strategy. As Albert Einstein once said, stupidity is best defined as going the same path and expecting to reach a different destination.

References

2. Gilman A. Therapeutic applications of chemical warfare agents. In: Federation Proceedings 1946 Jun; 5: 285-292.

3. Einhorn J. Nitrogen mustard: the origin of chemotherapy for cancer. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 1985 Jul 1;11(7):1375-8.

4. Frei E 3rd, Karon M, Levin RH, Freireich EJ, Taylor RJ, Hananian J, et al. The effectiveness of combinations of antileukemic agents in inducing and maintaining remission in children with acute leukemia. Blood. 1965 Nov;26(5):642-56.

5. Singh RK, Kumar S, Prasad DN, Bhardwaj TR. Therapeutic journery of nitrogen mustard as alkylating anticancer agents: Historic to future perspectives. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2018 May 10;151:401-33.

6. Henson ES, Gibson SB. Surviving cell death through epidermal growth factor (EGF) signal transduction pathways: implications for cancer therapy. Cellular Signalling. 2006 Dec 1;18(12):2089-97.

7. Otto T, Sicinski P. Cell cycle proteins as promising targets in cancer therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2017 Feb;17(2):93-115.

8. Mimeault M, Batra SK. New advances on critical implications of tumor-and metastasis-initiating cells in cancer progression, treatment resistance and disease recurrence. Histology and Histopathology. 2010 Aug;25(8):1057.

9. Vargas-Rondón N, Villegas VE, Rondón-Lagos M. The role of chromosomal instability in cancer and therapeutic responses. Cancers. 2018 Jan;10(1):4.

10. Stanta G, Bonin S. Overview on clinical relevance of intra-tumor heterogeneity. Frontiers in Medicine. 2018 Apr 6;5:85.

11. Morash M, Mitchell H, Beltran H, Elemento O, Pathak J. The role of next-generation sequencing in precision medicine: a review of outcomes in oncology. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2018 Sep;8(3):30.

12. Gharpure KM, Wu SY, Li C, Lopez-Berestein G, Sood AK. Nanotechnology: future of oncotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2015 Jul 15;21(14):3121-30.

13. Trevors JT, Saier Jr MH. Thermodynamic perspectives on genetic instructions, the laws of biology and diseased states. Comptes Rendus Biologies. 2011 Jan 1;334(1):1-5.

14. Gatenby RA, Frieden BR. The critical roles of information and nonequilibrium thermodynamics in evolution of living systems. Bulletin of Mathematical Biology. 2013 Apr 1;75(4):589-601.

15. Lane N, Martin W. The energetics of genome complexity. Nature. 2010 Oct;467(7318):929-34.

16. Lineweaver CH, Egan CA. Life, gravity and the second law of thermodynamics. Physics of Life Reviews. 2008 Dec 1;5(4):225-42.

17. Davies PC, Rieper E, Tuszynski JA. Self-organization and entropy reduction in a living cell. Biosystems. 2013 Jan 1;111(1):1-0.

18. National Academy of Sciences. The Origin of the Universe, Earth, and Life. In Science and Creationism: A View from the National Academy of Sciences (2nd ed.). The National Academies Press. 1999.

19. Daut J. The living cell as an energy-transducing machine. A minimal model of myocardial metabolism. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Reviews on Bioenergetics. 1987 Jan 1;895(1):41-62.

20. Wohl I, Sherman E. ATP-dependent diffusion entropy and homogeneity in living cells. Entropy. 2019 Oct;21(10):962.

21. López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013 Jun 6;153(6):1194-217.

22. Ganesan A. Epigenetics: the first 25 centuries. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2018 Jun 5;373(1748).

23. Seo J, Jin D, Choi CH, Lee H. Integration of microRNA, mRNA, and protein expression data for the identification of cancer-related microRNAs. PLoS One. 2017 Jan 5;12(1):e0168412.

24. Narula J, Williams CJ, Tiwari A, Marks-Bluth J, Pimanda JE, Igoshin OA. Mathematical model of a gene regulatory network reconciles effects of genetic perturbations on hematopoietic stem cell emergence. Developmental Biology. 2013 Jul 15;379(2):258-69.

25. De Las Rivas J, Fontanillo C. Protein–protein interactions essentials: key concepts to building and analyzing interactome networks. PLoS Computational Biology. 2010 Jun 24;6(6):e1000807.

26. Wehrl A. General properties of entropy. Reviews of Modern Physics. 1978 Apr 1;50(2):221.

27. de Almeida LC, Calil FA, Machado-Neto JA, Costa-Lotufo LV. DNA damaging agents and DNA repair: from carcinogenesis to cancer therapy. Cancer Genetics. 2021 Apr;252-253:6-24.

28. Kiraly O, Gong G, Olipitz W, Muthupalani S, Engelward BP. Inflammation-induced cell proliferation potentiates DNA damage-induced mutations in vivo. PLoS Genetics. 2015 Feb 3;11(2):e1004901.

29. Gryder BE, Nelson CW, Shepard SS. Biosemiotic entropy of the genome: mutations and epigenetic imbalances resulting in cancer. Entropy. 2013 Jan;15(1):234-61.

30. Janin J, Bahadur RP, Chakrabarti P. Protein–protein interaction and quaternary structure. Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 2008 May;41(2):133-80.

31. Akimov SA, Molotkovsky RJ, Kuzmin PI, Galimzyanov TR, Batishchev OV. Continuum models of membrane fusion: Evolution of the theory. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020 Jan;21(11):3875.

32. Nair A, Chauhan P, Saha B, Kubatzky KF. Conceptual evolution of cell signaling. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019 Jan;20(13):3292.

33. Wilkinson ME, Charenton C, Nagai K. RNA Splicing by the Spliceosome. Annual Review of Biochemistry. 2020 Jun 20;89:359-88.

34. Liu Q, Zhang W, Wu Z, Liu H, Hu H, Shi H, et al. Construction of a circular RNA‐microRNA‐messengerRNA regulatory network in stomach adenocarcinoma. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2020 Feb;121(2):1317-31.

35. Jones PA, Issa JP, Baylin S. Targeting the cancer epigenome for therapy. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2016 Oct;17(10):630-41.

36. Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2007 Feb;7(2):79-94.

37. Budenholzer L, Cheng CL, Li Y, Hochstrasser M. Proteasome structure and assembly. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2017 Nov 10;429(22):3500-24.

38. Nandi D, Tahiliani P, Kumar A, Chandu D. The ubiquitin-proteasome system. Journal of Biosciences. 2006 Mar 1;31(1):137-55.

39. Weitzman JK. Krebs citric acid cycle: half a century and still turning. In: Biochem. Soc. Symp 1987 (Vol. 54, pp. 1-198).

40. Hatefi Y. ATP synthesis in mitochondria. EJB Reviews 1993. 1994:201-9.

41. Pavin N, Tolić IM. Mechanobiology of the mitotic spindle. Dev Cell. 2021 Jan 25;56(2):192-201.

42. Goodson HV, Jonasson EM. Microtubules and microtubule-associated proteins. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2018 Jun 1;10(6):a022608.

43. Hara M, Fukagawa T. Dynamics of kinetochore structure and its regulations during mitotic progression. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2020 Feb 12:1-5.

44. Bloom K, Costanzo V. Centromere structure and function. Centromeres and Kinetochores. 2017:515-39.

45. Regolini M. The Centrosome as a Geometry Organizer. The Golgi Apparatus and Centriole. 2019:253-76.

46. Giardini MA, Segatto M, Da Silva MS, Nunes VS, Cano MI. Telomere and telomerase biology. Progress in Molecular Biology and Translational Science. 2014 Jan 1;125:1-40.

47. Afrasiabi, K. Fundamentals of Living and Nonliving Universes from Black Holes to Cancer. Page Publishing, Inc. 2018.

48. Ali MM, Kang DK, Tsang K, Fu M, Karp JM, Zhao W. Cell‐surface sensors: lighting the cellular environment. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology. 2012 Sep;4(5):547-61.

49. Cheng F, Liu C, Shen B, Zhao Z. Investigating cellular network heterogeneity and modularity in cancer: a network entropy and unbalanced motif approach. BMC Systems Biology. 2016 Aug;10(3):301-11.

50. Umezawa Y. Genetically encoded optical probes for imaging cellular signaling pathways. Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 2005 Jun 15;20(12):2504-11.

51. Ogrodnik M. Cellular aging beyond cellular senescence: Markers of senescence prior to cell cycle arrest in vitro and in vivo. Aging Cell. 2021 Apr;20(4):e13338.

52. Shay JW. Telomeres and aging. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2018 Jun 1;52:1-7.

53. Lu W, Zhang Y, Liu D, Songyang Z, Wan M. Telomeres—structure, function, and regulation. Experimental Cell Research. 2013 Jan 15;319(2):133-41.

54. Victorelli S, Passos JF. Telomeres and cell senescence-size matters not. EBioMedicine. 2017 Jul 1;21:14-20.

55. West J, Bianconi G, Severini S, Teschendorff AE. Differential network entropy reveals cancer system hallmarks. Scientific Reports. 2012 Nov 13;2(1):1-8.

56. Blasco MA. Telomeres and human disease: ageing, cancer and beyond. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2005 Aug;6(8):611-22.

57. Nijman SM. Perturbation-driven entropy as a source of cancer cell heterogeneity. Trends in Cancer. 2020 Jun 1;6(6):454-61.

58. Bailey MH, Tokheim C, Porta-Pardo E, Sengupta S, Bertrand D, Weerasinghe A, et al. Comprehensive characterization of cancer driver genes and mutations. Cell. 2018 Apr 5;173(2):371-85.

59. Rhim JS. Neoplastic transformation of human cells in vitro. Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 1993 Jan 1;4(3):313-35.

60. Park Y, Lim S, Nam JW, Kim S. Measuring intratumor heterogeneity by network entropy using RNA-seq data. Scientific Reports. 2016 Nov 24;6(1):1-2.

61. Sasmita AO, Wong YP, Ling AP. Biomarkers and therapeutic advances in glioblastoma multiforme. Asia‐Pacific Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Feb;14(1):40-51.

62. Rich JN. Cancer stem cells: understanding tumor hierarchy and heterogeneity. Medicine. 2016 Sep;95(Suppl 1):S2-S7.

63. Trinh AL, Chen H, Chen Y, Hu Y, Li Z, Siegel ER, et al. Tracking functional tumor cell subpopulations of malignant glioma by phasor fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy of NADH. Cancers. 2017 Dec;9(12):168.

64. Chen YJ, Dalchau N, Srinivas N, Phillips A, Cardelli L, Soloveichik D,et al. Programmable chemical controllers made from DNA. Nature Nanotechnology. 2013 Oct;8(10):755-62.

65. Haley NE, Ouldridge TE, Ruiz IM, Geraldini A, Louis AA, Bath J, et al. Design of hidden thermodynamic driving for non-equilibrium systems via mismatch elimination during DNA strand displacement. Nature Communications. 2020 May 22;11(1):1-1.

66. Wei T, Cheng Q, Min YL, Olson EN, Siegwart DJ. Systemic nanoparticle delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoproteins for effective tissue specific genome editing. Nature Communications. 2020 Jun 26;11(1):1-2.

67. A Baudino T. Targeted cancer therapy: the next generation of cancer treatment. Current Drug Discovery Technologies. 2015 Mar 1;12(1):3-20.

68. Zhang H, Chen J. Current status and future directions of cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Cancer. 2018;9(10):1773.