Abstract

ERA is a robust tool in environmental decision-making, offering a quantitative framework for risk assessment and management. By separating scientific analysis from policymaking, ERA ensures objective evaluations of ecological risks. Whether dealing with prospective risks or retrospective assessments of past environmental damage, ERA provides a means to balance ecological protection with economic and social considerations. Moreover, integrating advanced monitoring techniques enhances ERA's ability to assess and mitigate the risks contaminants pose to ecosystems. ERA is a critical tool for environmental management, offering a structured yet flexible approach to evaluating the consequences of human actions on ecosystems. Its scientific rigor, transparency, and adaptability across scales make it invaluable for decision-makers, allowing for informed, sustainable development while ensuring ecological protection.

Keywords

Risk Assessment, Environment, Monitoring Methods, Biomarkers

ERA Framework

Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) is a key framework for evaluating the likelihood of adverse environmental impacts due to human activities. It offers a structured process incorporating several concepts and methodologies to assess environmental health, aiming for informed environmental protection and management decision-making [1].

Concepts in ERA

- Environmental Risk Assessment: ERA focuses on the likelihood of negative impacts on ecosystems, analyzing factors that may harm the environment due to anthropogenic activities. It evaluates the probability of adverse effects and enables decision-makers to mitigate risks [2].

- Environmental Value: This represents significant aspects of the ecosystem, including ecological, social, and economic importance. It highlights the potential consequences of their loss, beyond just monetary worth, encompassing cultural and ecological relevance, such as water supplies or species diversity.

- Indicators: Measurable parameters that show patterns or trends in environmental health, such as endangered species counts or land use changes. Indicators provide a way to assess and monitor ecological conditions, helping gauge risk and determine environmental trends.

- Natural Conditions: Defined as historical environmental states before European settlement, often used as a baseline in ERA. This includes variables like seasonal stream flows or biodiversity, offering a reference for understanding how current conditions deviate from the natural state.

- Pressures: These are human-induced factors that influence ecosystems, leading to cumulative impacts over time. Examples include land use changes, industrial development, and pollution.

- Risk: Refers to the likelihood of environmental degradation occurring. It is often measured through indicators and thresholds, helping identify the potential impact and severity of human actions on ecosystems.

- Risk Class: Categorizes risk levels, ranging from very low to very high, to help assess the severity of potential ecological damage. This classification system guides environmental management efforts, helping prioritize areas in need of intervention [3].

Environmental Principles in ERA

The Strengths and Process of Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)

**Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)** is a versatile and systematic framework designed to evaluate potential environmental impacts caused by human activities. ERA is essential for decision-making, enabling a balance between development and environmental protection. Its strengths and flexibility make it a widely used tool in environmental management [4].

Strengths of ERA

Flexibility and applicability:

- ERA can be applied at various scales, from large-scale provincial assessments to specific site-level analyses.

- It covers a wide range of environmental concerns, including biodiversity, water quality, and land use.

- The tool accommodates different funding levels, from quick assessments to comprehensive, detailed studies.

- ERA is adaptable for short-, medium-, or long-term projections, offering dynamic insights.

Public understanding and stakeholder engagement:

- The concept of “risk” or “threat” is simple and widely understood by the public, making ERA a transparent approach for communicating environmental risks and consequences.

- It provides explicit criteria for decision-making, promoting accountability, and ensuring stakeholders that the environmental effects of human activities are being systematically considered.

- ERA serves as a framework for improving dialogue between stakeholders and authorities on contentious environmental management or development issues [5].

Scientific rigor and accountability:

- ERA's structured approach builds a scientific foundation for decision-making that is valid, defensible, and replicable.

- It separates the assessment of risks from decision-making, making it easier to evaluate options objectively and transparently.

- The process acknowledges the assumptions and data used, which adds to its credibility and helps stakeholders understand the basis of the analysis.

Insight into Environmental-Human Interaction:

- ERA identifies and highlights the consequences of human activities on the environment, aiding in the identification of potential alternative management actions.

- It enhances understanding of the relationship between human activities and the ecosystem, helping in building sustainable management strategies [6].

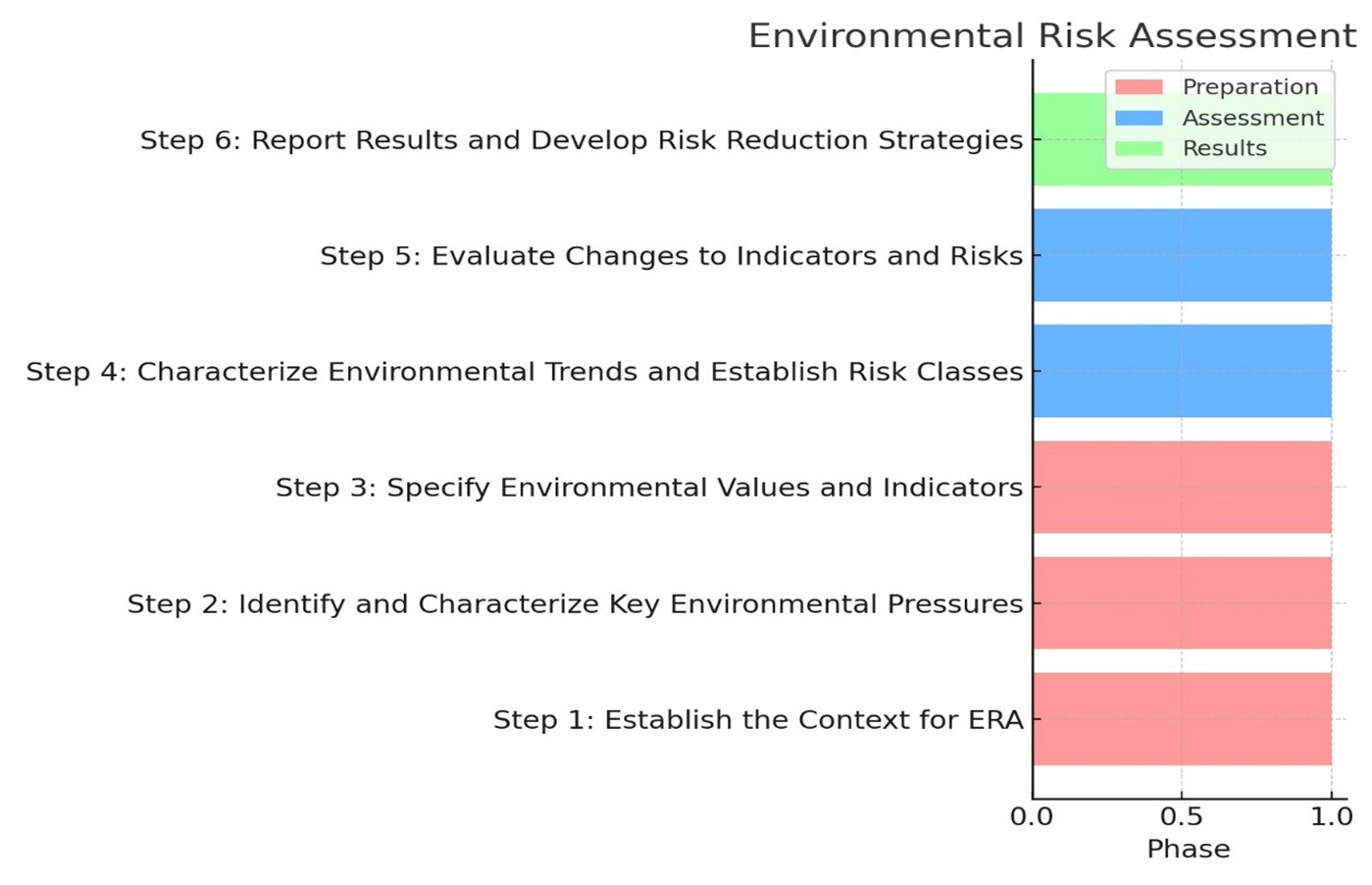

The ERA Process is Broken into Two Main Phases: **Preparation** and **Assessment**, Followed by Reporting the Results

- Preparation:

- Assessment:

- Results:

Step 1: Establish the Context for ERA: Define the scope, goals, and boundaries for the assessment, including the environmental issues at hand.

Step 2: Identify and Characterize Key Environmental Pressures: Recognize human-induced factors or activities that may stress the environment.

Step 3: Specify Environmental Values and Indicators: Choose the environmental values and corresponding indicators that will be used to measure environmental health and evaluate risks [7].

Figure 1. Environmental risk assessment process.

Step 4: Characterize Environmental Trends and Establish Risk Classes: Evaluate current and historical trends for the chosen indicators, and categorize the degree of risk (e.g., low, moderate, high).

Step 5: Evaluate Changes to Indicators and Risks: Analyze how the environmental indicators and risks may change under different scenarios, based on human activities and pressures [8].

Step 6: Report Results and Develop Risk Reduction Strategies: Present the findings of the ERA in a clear and actionable manner and propose strategies to mitigate or manage identified risks.

Health Risk Assessment (HRA) and Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)

**Health Risk Assessment (HRA)** has been a critical tool for evaluating the impact of environmental pollution on human health since its emergence in the 1980s. It establishes a direct link between pollution and health risks, providing a quantitative measure of how pollution affects human health. The method recommended by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) has become the standard for HRA studies worldwide. This approach is essential for water environment protection, pollution remediation, and risk management, allowing regulatory bodies to evaluate the risk levels of pollutants in water and take appropriate action.

Health Risk Assessment (HRA)

HRA helps to estimate the nature and probability of adverse health effects in humans exposed to chemicals in contaminated environments. By assessing water pollution's potential harm, HRA guides environmental authorities in managing water safety and public health. In practice, HRA is highly applicable in cases where water pollution is a significant concern, as it provides vital data on how pollutants affect human populations. For instance, by evaluating the levels of risk in water bodies and comparing them to accepted health thresholds, administrative bodies can prioritize cleanup efforts and ensure safer environments for human populations [9]. The adverse health effects on humans are linked to the inactivation of critical genes for survival. HRA and ERA need to assess the impact of xenobiotics on these essential genes for survival to reverse mitophagy and programmed cell death in the developing and developed world [10].

Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)

**Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)**, on the other hand, has gained prominence as society recognized that some chemicals—non-toxic to humans—could have harmful effects on the ecosystem. ERA focuses on the risk these chemicals pose to ecological resources like fish, birds, and forests, evaluating the impact of pollutants such as DDT or acid rain. ERA is divided into two major processes: risk analysis and risk management [11].

- -Risk analysis: involves identifying hazards, assessing the effects, and evaluating exposure levels to characterize the risk.

- -Risk management: focuses on developing regulatory measures to mitigate or prevent these risks based on the findings of the risk analysis.

Although predictive ERA is the most common form, there has been a growing interest in retrospective ERA. This form of ERA assesses pollution from past activities that continue to have adverse effects. Retrospective ERA primarily investigates the relationship between historical pollutants and their long-term ecological impacts, providing insights that can inform future risk management strategies. ERA is a critical tool for understanding and mitigating the risks posed by human activities to the environment. Driven by the need to allocate limited resources effectively, risk assessment helps distinguish between **risk** (the probability of harm occurring due to exposure) and **hazard** (the inherent potential to cause harm) [12]. ERA provides a systematic framework for evaluating the likelihood of ecological damage and comparing various risks, offering decision-makers a scientific basis for prioritizing actions and minimizing environmental harm [13].

Risk analysis vs. risk management: ERA separates risk analysis from risk management. Risk analysis is a scientific process that estimates the magnitude and probability of environmental effects, while risk management involves making decisions based on those analyses, balancing the risk against the cost of mitigation. This separation ensures transparency and objectivity in environmental decision-making [14].

Application of ERA to Chemicals

ERA has primarily been used to assess the impact of chemicals on ecosystems. International bodies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have been at the forefront of developing ERA methodologies. ERA provides a quantitative basis for comparing risks, essential for balancing environmental protection with economic considerations [11]. Franke et al. [15] highlighted the importance of clearly defined and measurable endpoints (e.g., species diversity, population dynamics) in ERA to avoid ambiguity in environmental assessments.

Predictive vs. retrospective assessments

Traditionally, ERA has been used for predictive assessments, which estimate the nature and likelihood of future impacts (e.g., PEC/PNEC assessments). However, there has been a growing emphasis on retrospective assessments. These are conducted on past human activities affecting ecosystems, such as legacy pollutants, acid rain, or pesticides [16]. Retrospective ERA typically follows three approaches:

- Source-driven assessments: Start with a known pollution source and trace the effects.

- Exposure-driven assessments: Investigate cases where exposure is evident without identifying the source or its effects.

Effects-driven assessments: Begin with observed environmental damage (e.g., declining species populations) and work backward to identify the cause [15,17].

Environmental Monitoring Methods

To assess environmental risks, several monitoring techniques are employed:

- Chemical Monitoring (CM): Measures the levels of known contaminants in the environment.

- Bioaccumulation Monitoring (BAM): Examines contaminant levels in organisms and assesses bioaccumulation risks.

- Biological Effect Monitoring (BEM): Identifies early biological changes (biomarkers) that indicate exposure to contaminants.

- Health Monitoring (HM): Detects irreversible damage or diseases in organisms caused by pollutants.

- Ecosystem Monitoring (EM): Evaluates ecosystem health by examining biodiversity, species composition, and population densities [18].

These monitoring methods, especially when combined with biomarkers and bioaccumulation data, offer a comprehensive approach to assessing the ongoing impacts of contaminants in ecosystems and help to classify environmental quality [19].

Fish Bioaccumulation Markers and Their Role in Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA)

In the context of Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA), fish bioaccumulation markers serve as crucial indicators for assessing exposure to environmental contaminants. These markers help understand how harmful chemicals accumulate in aquatic organisms and provide insight into the potential ecological impacts. Key concepts such as bioaccumulation, bioconcentration, biomagnification, and bioavailability highlight the processes through which chemicals interact with aquatic ecosystems, particularly with fish populations [20,21].

Bioaccumulation

Bioaccumulation refers to the accumulation of persistent hydrophobic chemicals in aquatic organisms through mechanisms such as direct uptake from water via gills or skin (bioconcentration), ingestion of suspended particles, or consumption of contaminated food (biomagnification). These chemicals, including PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), may not produce immediate toxic effects but can cause long-term damage, often affecting higher trophic levels, such as birds or fish eggs [22]. The rate at which these chemicals accumulate in biota is influenced by factors like uptake and elimination kinetics, which are specific to both the chemical and the organism [23].

Bioconcentration

Bioconcentration occurs when chemicals are absorbed from water into an organism's tissues. The bioconcentration factor (BCF) is the ratio of a chemical's concentration in the organism to its concentration in water at a steady state. This process is largely driven by passive diffusion, like oxygen uptake, with chemicals accumulating in the lipid-rich tissues of fish. Studies have shown that factors like oxygen levels in the water and the lipid content of biological membranes significantly influence the rate of chemical uptake [24,25].

Biomagnification

Biomagnification describes the process by which chemicals are absorbed from food and accumulate in organisms at higher concentrations than in their diet. The biomagnification factor (BMF) is determined by the balance between the efficiency of chemical uptake from food and the rate of clearance from the organism. This phenomenon is particularly relevant for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) that do not break down easily and thus remain in the ecosystem, magnifying their effects as they move up the food chain [26,27].

Bioavailability

Bioavailability refers to the portion of a chemical present in the environment that can be absorbed by an organism. The bioavailability of a chemical affects its **bioaccumulation potential**, and variations in bioavailability can lead to underestimations of bioconcentration. This parameter is critical for producing accurate exposure assessments, as chemicals in sediments or bound to particles may not be readily available for uptake by aquatic organisms [28,29].

Conclusion

In conclusion, HRA and ERA serve as critical tools in evaluating and managing risks posed by environmental pollution, addressing both human health and ecological well-being. HRA provides a framework to assess health risks from environmental pollutants and informs public health protection strategies. Meanwhile, ERA offers a comprehensive view of how pollutants affect ecosystems, supporting regulatory measures to safeguard natural resources. Together, these assessments form a unified approach to environmental protection and sustainable health management. Fish bioaccumulation markers play a vital role in assessing ecological risks, offering insights into how contaminants accumulate and transfer through aquatic systems. Key processes like bioaccumulation, bioconcentration, and biomagnification help understand pollutant behavior and their long-term effects on aquatic life and food webs. This knowledge supports informed decision-making for mitigating environmental risks and ensuring the preservation of ecosystem health.

References

2. Linkov I, Trump BD, Wender BA, Seager TP, Kennedy AJ, Keisler JM. Integrate life-cycle assessment and risk analysis results, not methods. Nature Nanotechnology. 2017 Aug;12(8):740-3.

3. Qian L, Zeng X, Ding Y, Peng L. Mapping the knowledge of ecosystem service-based ecological risk assessment: scientometric analysis in CiteSpace, VOSviewer, and SciMAT. Frontiers in Environmental Science. 2023 Nov 30; 11:1326425.

4. Talukdar S, Rahman A, Bera S, Ramana GV, Prashar A. Environmental Risk and Resilience in a Changing World: A Comprehensive Exploration and Interplay of Challenges and Strategies. In: Talukdar S, Rahman A, Bera S, Ramana GV, Prashar A. Environmental Risk and Resilience in the Changing World: Integrated Geospatial AI and Multidimensional Approach. Cham: Springer Nature; 2024. p. 3-17.

5. Cundy AB, Bardos RP, Church A, Puschenreiter M, Friesl-Hanl W, Müller I, et al. Developing principles of sustainability and stakeholder engagement for "gentle" remediation approaches: the European context. J Environ Manage. 2013 Nov 15; 129:283-91.

6. Liwång H, Ringsberg JW, Norsell M. Quantitative risk analysis–Ship security analysis for effective risk control options. Safety Science. 2013 Oct 1; 58:98-112.

7. Manuele FA. Chapter 1: Risk assessments: their significance and the role of the safety professional. In: Popov G, Lyon BK, Hollcraft B (eds). Risk assessment: a practical guide to assessing operational risks. Hoboken: Wiley; 2016. p. 1-22.

8. Ferreira V, Barreira AP, Loures L, Antunes D, Panagopoulos T. Stakeholders’ engagement on nature-based solutions: A systematic literature review. Sustainability. 2020 Jan 15;12(2):640.

9. Ben Y, Fu C, Hu M, Liu L, Wong MH, Zheng C. Human health risk assessment of antibiotic resistance associated with antibiotic residues in the environment: A review. Environ Res. 2019 Feb;169:483-93.

10. Martins IJ. Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics. 2017 Aug 1;3(3):1-8.

11. Breedveld L. Combining LCA and RA for the integrated risk management of emerging technologies. Journal of Risk Research. 2013 Apr 1;16(3-4):459-68.

12. Harder AT, Knorth EJ, Kalverboer ME. Risky or needy? Dynamic risk factors and delinquent behavior of adolescents in secure residential youth care. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology. 2015 Sep;59(10):1047-65.

13. Kangas AS, Kangas J. Probability, possibility and evidence: approaches to consider risk and uncertainty in forestry decision analysis. Forest Policy and Economics. 2004 Mar 1;6(2):169-88.

14. Gasparatos A, Doll CN, Esteban M, Ahmed A, Olang TA. Renewable energy and biodiversity: Implications for transitioning to a Green Economy. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews. 2017 Apr 1;70:161-84.

15. Franke C, Studinger G, Berger G, Böhling S, Bruckmann U, Cohors-Fresenborg D, et al. The assessment of bioaccumulation. Chemosphere. 1994 Oct 1;29(7):1501-14.

16. Hernández AF, Tsatsakis AM. Human exposure to chemical mixtures: Challenges for the integration of toxicology with epidemiology data in risk assessment. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017 May;103:188-93.

17. Ward PJ, Blauhut V, Bloemendaal N, Daniell JE, de Ruiter MC, Duncan MJ, et al. Natural hazard risk assessments at the global scale. Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences. 2020 Apr 22;20(4):1069-96.

18. Khan A, Gupta S, Gupta SK. Multi-hazard disaster studies: Monitoring, detection, recovery, and management, based on emerging technologies and optimal techniques. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2020 Aug 1;47:101642.

19. Papathoma-Köhle M, Promper C, Glade T. A common methodology for risk assessment and mapping of climate change related hazards—implications for climate change adaptation policies. Climate. 2016 Feb 2;4(1):8.

20. Bjørn A, Owsianiak M, Molin C, Laurent A. Main characteristics of LCA. Life Cycle Assessment: Theory and Practice. 2018:9-16.

21. Abdel-Kader. Assessment and monitoring of land degradation in the northwest coast region, Egypt using Earth observations data. Egypt J Remote Sens Sp Sci. 2019;22:165-73.

22. Tillitt DE, Giesy JP, Ankley GT. Bioaccumulation of PCBs and Their Effects on Fish Reproduction and Development. Environmental Health Perspectives. 1992;103(Suppl 4):121-30.

23. Horwitz P, Finlayson CM. Wetlands as settings for human health: incorporating ecosystem services and health impact assessment into water resource management. BioScience. 2011 Sep 1;61(9):678-88.

24. Boese BL, Lee H, Specht DT, Randall R, Pelletier J. Evaluation of PCB Exposure Pathways in Benthic Organisms: Uptake via Sediment and Water. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. 1988;7(1):115-28.

25. Kowalska A, Grobelak A. Organic matter decomposition under warming climatic conditions. In: Prasad MNV, Pietrzykowski M, eds. Climate Change and Soil Interactions. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. pp. 397-412.

26. Sijm DT, Seinen W, Opperhuizen A. Life-cycle biomagnification study in fish. Environmental Science & Technology. 1992 Nov;26(11):2162-74.

27. Denmark OF. Environmental impacts on the genome and epigenome: mechanisms and risks. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2011;52(1):13-87.

28. Kristensen P, Tyle H. Bioavailability and Ecotoxicology of Hydrophobic Organic Chemicals: The Role of Sediment Sorption in Contaminant Fate and Bioavailability. Marine Pollution Bulletin. 1991;22(11):555-9.

29. Harder R, Holmquist H, Molander S, Svanström M, Peters GM. Review of Environmental Assessment Case Studies Blending Elements of Risk Assessment and Life Cycle Assessment. Environ Sci Technol. 2015 Nov 17;49(22):13083-93.