Abstract

Thyroid storm is a rare but potentially life-threatening form of thyrotoxicosis. The presence of excessive thyroid hormones leads to toxic direct and indirect effects on the cardiovascular system resulting in entity known as thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy (TCM). The end stage of TCM results in cardiorespiratory failure from cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema. Such outcomes have been rescued through mechanical circulatory support via extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). We describe a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old female who presented de-novo in thyroid storm and rapid atrial fibrillation, arrested within hours of presentation, was placed emergently on extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) via veno-arterial ECMO, and made a full neurological and cardiac recovery. TCM can be very challenging to treat medically with spiralling effects of tachyarrhythmia and worsening cardiac output leading to decompensated heart failure. TCM is often reversible once euthyroid physiology is achieved. It also appears to affect relatively younger patients with the average age of about 50 years. Mechanical support through means of ECMO should be strongly considered in patients presenting in cardiorespiratory failure from thyroid storm in ECMO-capable centres.

Keywords

Thyroid storm, Cardiac arrest, Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Introduction

Thyroid storm is potentially a fatal manifestation of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm is rare with reported incidence of approximately 0.6/100,000 persons per year and occur in relatively young patients with the average age of 50 years [1]. Thyroid storm often presents in patients with underlying thyroid disease, most commonly being Grave’s disease. Due to the presence of excessive thyroid hormones, the body transforms into a hypermetabolic state. Clinical presentation can be nonspecific with signs and symptoms of fever, tachycardia, palpitations, fatigue, dyspnea, and gastrointestinal upset; but in the most severe cases feature end-organ dysfunction such as hepatic failure, neurological deterioration and cardiorespiratory failure. Patients with thyrotoxicosis presenting in cardiorespiratory failure have mortality rates as high as 30% [2]. We report a case of a previously healthy 35-year-old female who presented to our emergency department (ED) in rapid atrial fibrillation (AF) and thyroid storm, who then decompensated rapidly into cardiac arrest, was placed on extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation (ECPR) via veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) and made a full neurological and cardiac recovery. We will briefly review the pathophysiology and management of cardiorespiratory failure in thyroid storm, as well as the current literature behind the utilization of ECMO in such cases.

Case Presentation

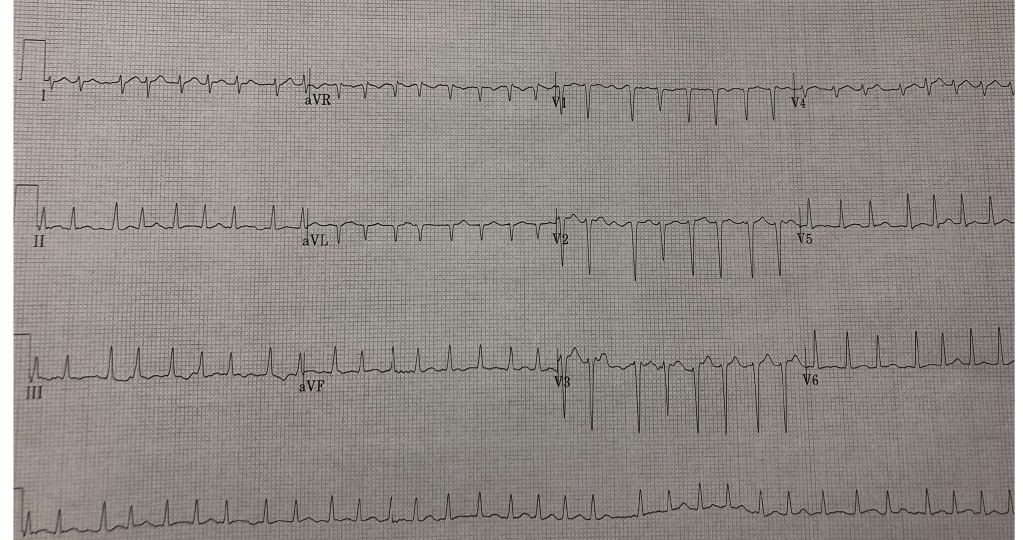

A 35-year-old Filipino female walked into our ED with a 2-week history of palpitations, dyspnea and peripheral edema. She was previously healthy, with no past medical history of thyroid disease, and reported no drug abuse or medication use. Her initial vital signs were a heart rate (HR) of 190-220 bpm in rapid AF (ECG shown in Figure 1), blood pressure of 150/70 mmHg, O2 saturation at 92% on room air, respiratory rate of 24 and temperature of 37.5°C. Her Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale was 75. Her bloodwork revealed a TSH that was non-detectable at <0.01 (normal range 0.34-4.82 mU/L), a free T4 of 100.8 (normal range 10.0-20.0 pmol/L) and free T3 of 16.3 (normal range 3.5-6.5 pmol/L). The rest of her bloodwork results are summarized in Table 1.

Figure1: Initial ECG.

|

|

Patient |

Normal range |

|

INR |

2.4 |

(0.9-1.2) |

|

Creatinine (mmol/L) |

67 |

40-95 |

|

Alkaline Phosphatase (U/L) |

284 |

30-135 |

|

Bilirubin, total (mmol/L) |

96 |

<20 |

|

Bilirubin, direct (mmol/L) |

33 |

0-5 |

|

Alanine Aminotransferase (U/L) |

97 |

10-45 |

|

Asparatate Aminotranferase (U/L) |

142 |

10-38 |

|

Lactate Dehydrogenase (U/L) |

360 |

90-240 |

|

Creatine Kinase (U/L) |

297 |

25-250 |

|

Troponin I (mg/L) |

0.05 |

<0.02 |

|

Beta Natriuretic Peptide (ng/L) |

657 |

<37 |

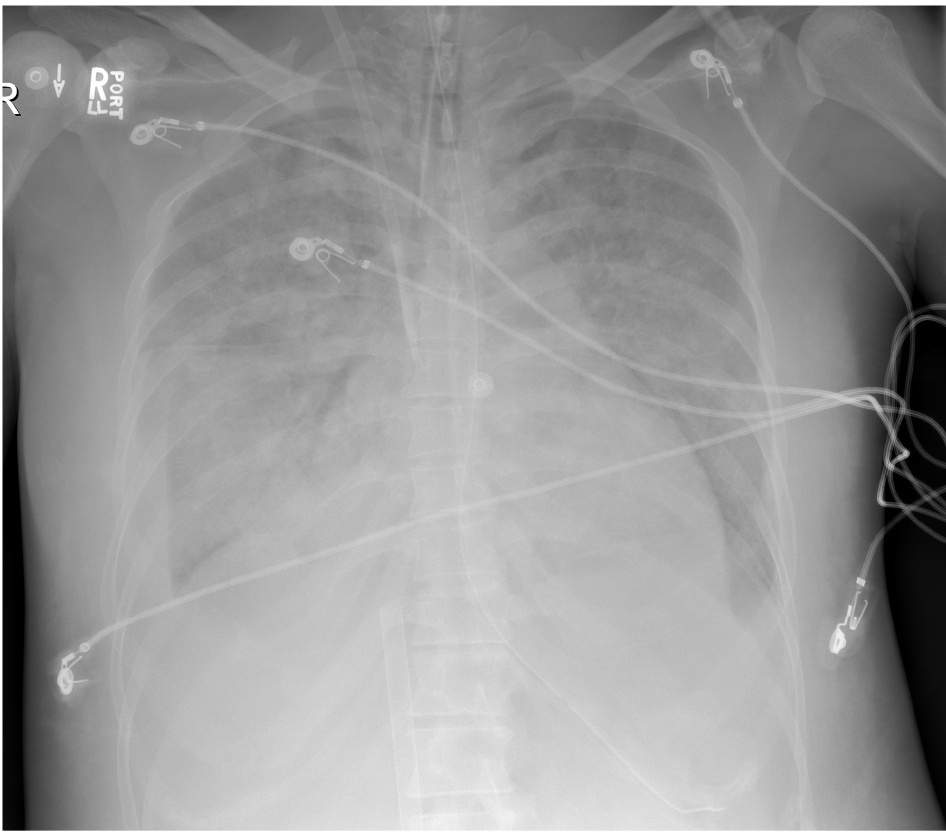

A diagnosis of thyroid storm was made, the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) was consulted and while in the ED, she was treated with intravenous (IV) doses of furosemide and metoprolol, and placed on bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) ventilation. Her arterial blood gas was 7.17/18/300/6 while on 100% FiO2 with a lactate level of 10.8 (normal 0.5-1.6 mmol/L). Shortly upon arriving to the ICU, and about 6 hours after presenting to the ED, she had a witnessed pulseless electrical activity (PEA) arrest. She received 5 rounds of CPR, a total of 3 mg epinephrine and was intubated. The hospital’s ECPR team was activated. There was return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) at 10 minutes. She then re-arrested within minutes of her initial ROSC and was placed on a LUCASÓ device for mechanical CPR. By 29 minutes into her second arrest, she was successfully cannulated and received ECPR via VA-ECMO. The patient was in dense cardiogenic shock on milrinone, epinephrine, norepinephrine and vasopressin infusions. A post-cannulation bedside transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was performed and revealed severe biventricular failure with a left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF) of approximately 5%. She was cooled to a temperature of 35-36 degrees Celsius for 24 hours. Anti-thyroid medications consisting of thioamides, potassium iodide (Lugol’s) solution and corticosteroids were initiated. Due to her metabolic acidosis and anuric renal failure, she was placed onto continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT). Her chest X-ray following intubation, cannulation and ROSC is shown in Figure 2. She was negative for SARS-CoV 2 virus on both nasopharyngeal swab and tracheal aspirate.

Figure 2: Chest X-Ray post arrest.

The next morning about 12 hours following the arrest, her cardiac function was already improving. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a LVEF of 20% while on de-escalating doses of vasopressor and ionotropic support. Over the course of the day however, her right lower leg became pulseless and developed compartment syndrome. An attempt to place a distal perfusion catheter to the lower leg was unsuccessful due to anatomical difficulty. A weaning trial was performed with bedside TEE. While on milrinone at 0.25 mcg/kg/min and norepinephrine at 6 mcg/min, with the ECMO flow rates turned down to 1 L/min, the patient had a LVEF of 45-50% and a LV outflow tract velocity time integral of 14 cm (normal 18-22 cm) at a HR of 90-100 bpm. She was then taken to the OR for right lower leg fasciotomy for compartment syndrome and her right femoral artery was repaired. Her VA-ECMO cannulation sites were swapped from the right femoral artery and vein to the left femoral artery and vein. By end of Day 2 she was fully weaned off vasopressor and ionotropic support, her sedation was lightened, and she was found to be awake and obeying all four limbs.

By Day 3, she appeared ready for decannulation. A repeat TEE revealed normal LV function but some persistent RV dysfunction. A pulmonary artery (PA) catheter was inserted to further assess her cardiac function and filling pressures during weaning of VA-ECMO. She was found to have a cardiac index of 4.2 (normal 2.5-4.0 L/min/m2) and cardiac output of 7.1 L/min (normal 4.0-8.0 L/min) via continuous cardiac output monitoring. A mixed venous oxygen saturation was measured at 80%, pulmonary artery pressures of 38/15 mmHg, and a central venous pressure of 12 mmHg. She was successfully decannulated at 65 hours following her initial arrest.

Her TSH antibody assay came back positive, confirming the diagnosis of Grave’s disease. A thyroid ultrasound revealed no nodules or masses but only signs of thyroiditis. At Day 7 she was successfully extubated and tolerated her first run of intermittent hemodialysis without vasopressor support. On Day 11, a repeat TTE was performed and revealed a normal LVEF at 65% in sinus rhythm with a normal right ventricular size and function. On Day 16, a split-thickness skin graft was placed over her fasciotomy incision site. On Day 17 she was transferred to the ward. On Day 22, she had her last run of dialysis and fortunately has made a full renal recovery. On Day 24, she provided her signed consent to allow us to write this case report. On Day 36, she was discharged from hospital to a rehabilitation centre.

Discussion

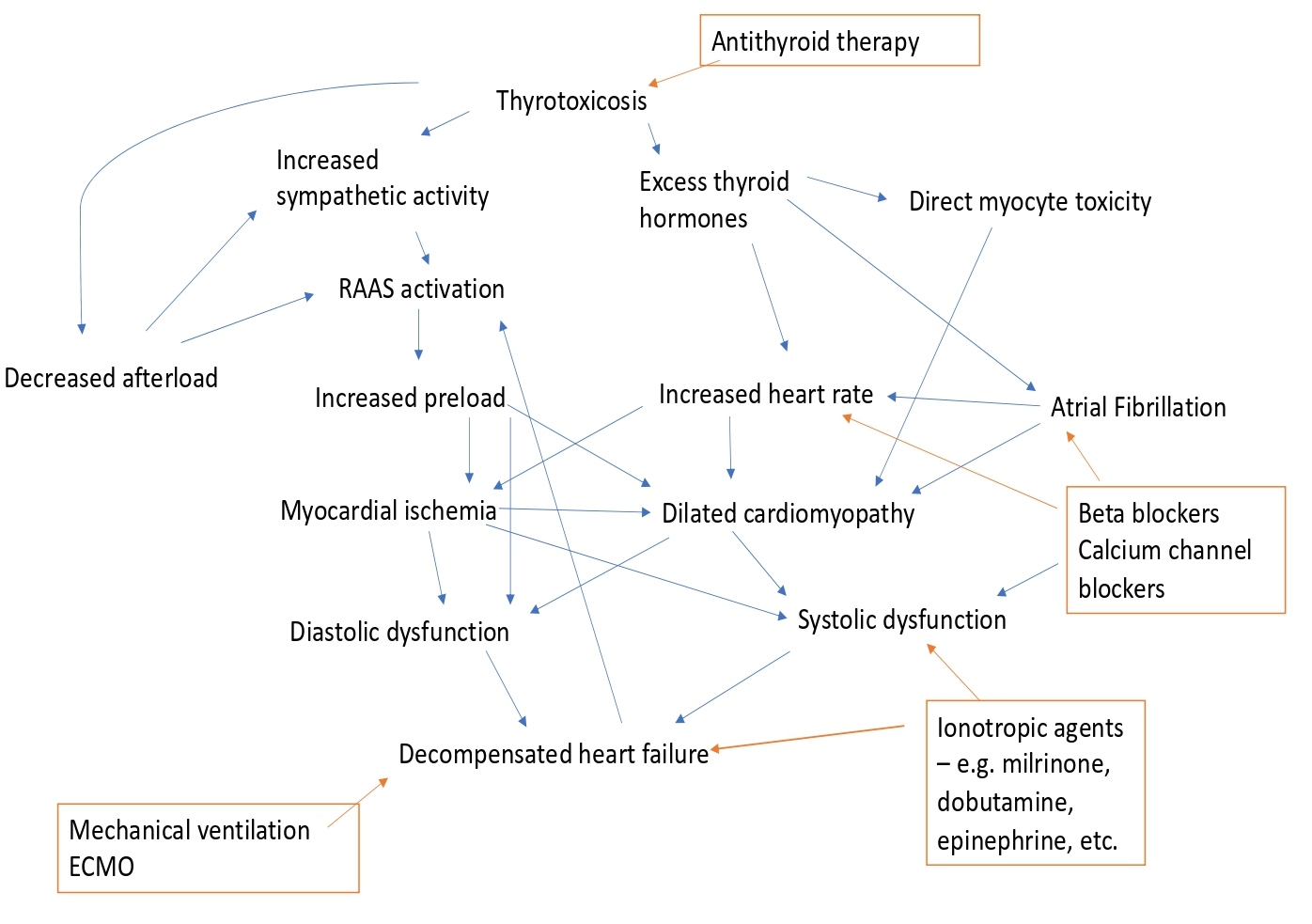

Thyroid hormones have both direct and indirect effects on the cardiovascular system. Thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy (TCM) has been previously described as a high output cardiac state. Specifically, during thyrotoxicosis, there is decreased systemic vascular resistance leading to decreased afterload, as well as increased preload from fluid and salt retention due to the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [3]. Furthermore, increased sympathetic activity and excess thyroid hormones at the cardiomyocytes can lead to excessive chronotropic and ionotropic effects leading to tachyarrhythmias and myocardial ischemia. Lastly, the development of rapid AF in thyrotoxicosis can precipitate further hemodynamic collapse due to loss of atrial kick, atrioventricular synchrony and HR control [4]. If all these mechanisms are not suppressed, the end result is a form of dilated cardiomyopathy with impaired systolic and diastolic function, manifesting as cardiorespiratory failure from cardiogenic shock and pulmonary edema (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Flow diagram depicting the potential mechanisms of thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy and subsequent decompensated heart failure and the management options. RAAS: Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System; Orange box denotes management options; Blue arrows denote worsening effect; Orange arrows denote improving effect.

The paramount step to treat thyroid storm is making the correct diagnosis. There is no standard guideline for the diagnosis of thyroid storm; however, two scoring systems have been derived to help facilitate this clinical diagnosis – the Busch and Wartofsky Point scale and the Japan Thyroid Association Thyroid storm criteria [5]. Following the recognition of thyroid storm, the mainstay treatments are to 1) achieve euthyroid state, 2) symptom control via beta blockade, and 3) provide supportive care to maintain end-organ perfusion [6]. A combination of thioamides, potassium iodide solution and corticosteroids are given to decrease thyroid hormone production, prevent T3 and T4 release, and stop T4 to T3 conversion, respectively. Unfortunately, these processes take time and do not have immediate effect. Thus, the immediate management is mostly symptom control and supportive care.

Beta-blockers are preferentially used to treat tachyarrhythmias. The 2016 Japanese Guidelines advocates to use esmolol over propranolol as it is short-acting and cardioselective [5]. However, beta blockade becomes difficult to tolerate once the patient develops decompensated heart failure. Uncontrolled tachyarrhythmias in the setting of cardiogenic shock can quickly spiral into circulatory collapse and cardiac arrest. Ionotropic agents like dobutamine, milrinone or epinephrine can further precipitate tachyarrhythmias, while anti-arrhythmics like beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers have negative ionotropic effects that can worsen cardiac output. Other agents such as digoxin can also be used but may not be as effective in lowering HR by increasing vagal tone in patients with high catecholamine driven states such as thyroid storm. This high catecholamine state also renders the use of electrical cardioversion similarly ineffective [7]. Amiodarone is a common anti-arrhythmic often used in the ICU for its more stable hemodynamic properties [8], but amiodarone itself contains iodine and has the potential to precipitate further hyperthyroid activity via the Jod-Basedow phenomenon [9]. However, amiodarone can be used once anti-thyroid therapy has taken effect and may be the most tolerable drug in treating rapid AF in patients with TCM and cardiogenic shock [7].

With fluid overload and decreased cardiac output, the development of pulmonary edema and respiratory failure may necessitate ventilatory support. Positive pressure ventilation can be helpful however the induction alone required for mechanical ventilation even with the use of low-dose anesthetics may still lead to circulatory collapse. In these patients who have decompensated into such dense cardiorespiratory failure despite full medical therapy, may only be salvageable through mechanical means via ECMO. In the last decade, ECMO has been used for metabolic indications such as thyroid storm [10-13]. The intent of ECMO in thyroid storm functions as a bridge towards recovery. In a recent case review by White et al. in 2018, there were 14 case reports of the use of ECMO in management of thyroid storm. The survival to discharge rate was 78.5% (10/14) with 9 of the 10 survivors able to have a cardiac recovery with a LVEF of at least 50%. One patient had a presenting EF of <10% and had a 30% EF at discharge. The majority of thyroid storm cases were in patients with known thyroid disease with medication noncompliance as the primary trigger. Interestingly, the 3 patients described in the case series who did not survive were initially treated as heart failure and the diagnosis of thyroid storm was not made till 3-4 days after presentation, highlighting the importance of prompt diagnosis. What is remarkable with our case is the speed of recovery she had. In the case review by White et al, the mean time of ECMO support was 183 hours (range 82-432 hours). Our patient was decannulated at 65 hours towards a full cardiac and neurological recovery despite having a cumulative 40 minutes of arrest time.

Conclusion

Thyroid storm is a rare manifestation of thyrotoxicosis. Patients can rapidly decompensate into cardiorespiratory failure from TCM. The key to management is achieving euthyroid state through anti-thyroid medication, symptomatic treatment with beta-blockade and supportive care to maintain end-organ perfusion. Despite full medical therapy, patients may still deteriorate and be salvageable only through means of mechanical circulatory support via ECMO. We report a young female who made a full recovery with ECMO following circulatory collapse from thyroid storm. As TCM is reversible, the management of refractory cardiogenic shock with ECMO as a temporizing bridge towards recovery should be strongly considered.

References

2. Mohananey D, Smilowitz N, Villablanca PA, Bhatia N, Agrawal S, Baruah A, et al. Trends in the Incidence and In-Hospital Outcomes of Cardiogenic Shock Complicating Thyroid Storm. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 2017 Aug;354(2):159-64.

3. Ertek S, Cicero AF. State of the art paper Hyperthyroidism and cardiovascular complications: a narrative review on the basis of pathophysiology. aoms. 2013;5:944-52.

4. Dahl P, Danzi S, Klein I. Thyrotoxic cardiac disease. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2008 Sep;5(3):170-6.

5. Satoh T, Isozaki O, Suzuki A, Wakino S, Iburi T, Tsuboi K, et al. 2016 Guidelines for the management of thyroid storm from The Japan Thyroid Association and Japan Endocrine Society (First edition): The Japan Thyroid Association and Japan Endocrine Society Taskforce Committee for the establishment of diagnostic criteria and nationwide surveys for thyroid storm [Opinion]. Endocr J. 2016;63(12):1025-64.

6. Bourcier S, Coutrot M, Kimmoun A, Sonneville R, de Montmollin E, Persichini R, et al. Thyroid Storm in the ICU: A Retrospective Multicenter Study. Critical Care Medicine. 2020 Jan;48(1):83-90.

7. Parmar MS. Thyrotoxic atrial fibrillation. MedGenMed. 2005 Jan 4;7(1):74.

8. Bosch NA, Cimini J, Walkey AJ. Atrial Fibrillation in the ICU. Chest. 2018 Dec;154(6):1424-34.

9. Jabrocka-Hybel A, Bednarczuk T, Bartalena L, Pach D, Ruchała M, Kamiński G, et al. Amiodarone and the thyroid. Endokrynol Pol. 2015;66(2):176-86.

10. Pong. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Hyperthyroidism-Related Cardiomyopathy: Two Case Reports. J Endocrinol Metab. 2013; Available from: http://www.jofem.org/index.php/jofem/article/view/144

11. Chao A, Wang CH, You HC, Chou NK, Yu HY, Chi NH, et al. Highlighting Indication of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in endocrine emergencies. Scientific reports. 2015 Aug 24;5(1):1-8.

12. Kiriyama H, Amiya E, Hatano M, Hosoya Y, Maki H, Nitta D, et al. Rapid Improvement of thyroid storm-related hemodynamic collapse by aggressive anti-thyroid therapy including steroid pulse: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Jun;96(22):e7053.

13. Genev I, Lundholm MD, Emanuele MA, McGee E, Mathew V. Thyrotoxicosis-induced cardiomyopathy treated with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Heart & Lung. 2020 Mar;49(2):165-6.