Abstract

Virus infections represent a serious threat for human health, causing immense costs and burdens for health systems. Viral diseases and their treatment are therefore of global interest, that extensively increased with the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic at the end of 2019. About one third of myocarditis cases originate in infections caused by the enterovirus Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3). The effects of CVB3 on the human pacemaker have been studied in detail. In human induced pluripotent stem cell derived pacemaker like cells, the pacemaker ion channel (HCN4) location has been found to be switched from membranous, to autophagosomal in a Rab7 dependant manner. Two CVB3 proteins have been of special interest, one being highly conserved in enteroviruses (CVB3 2C). Understanding of the CVB3 infection mechanism is therefore beneficial for the development of antiviral therapies and antiviral drugs. Additionally, the found mechanisms might potentially be transferable on other enteroviruses, providing therapy options for enteroviruses in general.

Keywords

Heart disease, Sinoatrial node, HCN4, Enterovirus, Coxsackievirus, Rab, GTPase

Background

Since the end of 2019, we have been in the midst of a global pandemic caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, which has caused immense costs for the global health system and has led to the death of many people. Since then, the number of publications dealing with viral diseases has risen sharply and the field of virology has become visible, partly because research into therapies and vaccinations against viral infections is now in the public spotlight.

Bacterial infections have been treatable since the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming in 1928. In contrast there are hardly any effective treatment options or antiviral agents for viral infections, as their development is very complicated and costly, while they are only effective against a few viral variants [1,2]. Even though research in this field has received a boost from the Corona pandemic, specific investigation is still in its infancy.

Peischard et al. investigated viral effects of the Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3), a virus belonging to the genus of enterovirus, which is causing myocarditis, cardiac arrhythmias, and heart failure [3-5]. About 25% of viral myocarditis cases originate from enteroviral infections. About 9% of patients develop dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) and up to 12% of sudden cardiac deaths in young adults have been linked to myocarditis. The most commonly found virus in patients suffering from viral myocarditis is CVB3 [6].

In a preliminary study, a system for investigating viral effects in human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes (hiPSC-CM) was implemented aiming to uncover new viral mechanisms of infection under controlled conditions [5]. In a pioneering work, the inducible CVB3 genome was introduced into a hiPSC line to enable highly controlled experiments in hiPSC derived cardiomyocytes [5]. In their recent work, Peischard et al. used the aforementioned viral expression system to investigate CVB3-induced cardiac dysfunction, focusing on the initiation process of cardiac excitation, in the sinoatrial node (SAN) [8].

Focus on Pacemaker-like Cells and HCN4

The heart is a complex organ consisting of a variety of tissues, each having a specific task. These tissues work together to ensure sufficient blood flow to supply the body with nutrients and oxygen. This blood flow is generated by the heartbeat (cardiac contraction). The induction of cardiac contraction is achieved by the SAN, where the specialized cardiac pacemaker cells are located [9]. Pacemaker cells express the hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel 4 (HCN4), which is important for controlled depolarization towards the action potential threshold. Inherited mutations can cause HCN4 dysfunction and bradycardia. So-called channelopathies have been described in the literature for causing a variety of cardiac dysfunctions and other diseases such as long QT-syndrome or cystic fibrosis [10-14]. On the other hand, ion channels, such as HCN4 can be modulated by a variety of small molecules (agonists and antagonists) and thus represent an interesting target for the treatment of the aforementioned diseases [15]. Modulation can be achieved by direct functional modification of the HCN4 protein or by modulation of HCN4 channel trafficking [16]. Both approaches seem attractive to compensate for CVB3 mediated HCN4 inhibition. Another source for cardiac dysfunctions can be found in pathogens, one of which is CVB3 [7,17].

With their new model of hiPSC-derived pacemaker-like cells and their ability to control the CVB3 expression level, Peischard et al. enable research on enteroviral infection of cardiac pacemaker cells. This was impossible before due to lack of sample material and safety regulations. They were able to pin down the virus-host interaction to specific alterations in ion channel function of HCN4, the main pacemaker channel [8,18,19]. Consequently, HCN4 has been analyzed as a target for treating CVB3-induced cardiac dysfunctions such as bradycardia and sinus block, which can mimic the pathomechanism in developing embryos and patients alike [20-22].

Scientific Approach

To investigate pacemaker activity under viral induction, Peischard et al. developed a protocol for trans-differentiation of the hiPSC line SFS.1/ CVB3ΔVP0 in either ventricular-like or pacemaker-like cells based on a protocol from Zhang et al. and Schweizer et al. [23-25]. Quality control of these cell types was performed visually, by phenotype, and by immunostainings as well as analysis using immunofluorescence imaging and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Pacemaker-like cells showed a characteristic elongated shape, lacked the widespread contractile network characteristics, and expressed connexin 40, connexin 43 and connexin 45. Especially the expression of connexin 45 was emphasized, as connexin 45 has been described as a SAN-specific marker protein [26]. Apart from the expression of connexins, cardiac-specific ion channels (HCN4, Nav1.5, Cav1.2) were identified in pacemaker like cells using immunofluorescence staining and imaging. Cellular contraction behavior showed fast contraction with precise rhythm in pacemaker-like cells. Taken together, the basal characterization of the hiSPC-derived pacemaker-like cells shows characteristics of SAN cells.

As CVB3 is known for affecting the heart, causing bradycardia and heart failure [27,20], Peischard et al. investigated viral effects by induction of CBV3 expression for 5 days in hiPSC-derived pacemaker-like cells [8]. After induction, pacemaker-specific HCN4 showed significantly lower plasma membrane localization, but accumulation of HCN4-positive aggregates in the cytoplasm compared to non-induced cells. Electrochemical characterization of cellular activity by multi-electrode array (MEA) clearly demonstrated loss of HCN4 function in CVB3-expressing hiPSC-derived pacemaker-like cells.

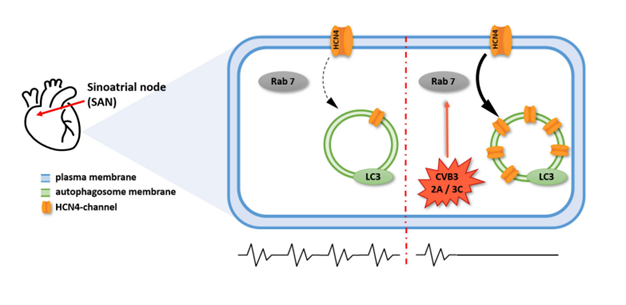

Based on the decreased membrane localization and cytoplasmic accumulation as well as the impairment of HCN4 function caused by CVB3, the authors hypothesized that CVB3 interferes with HCN4 expression and/or transport (Figure 1).

Two electrode voltage clamp (TEVC) screening identified the CVB3 proteins 2C and 3A to be mainly responsible for the HCN4 loss of function. Interestingly, in TEVC recordings only overall HCN4 activity was found to be altered but not channel kinetics, which led to the assumption that channel trafficking might be altered by CVB3 expression rather than structure and function of HCN4. Since CVB3-2C and CVB3-3A have previously been associated with the formation of autophagosomes and viral replication vesicles [28,29], it was tested whether cytoplasmic HCN4 accumulation was induced by the formation of autophagosomes through CVB3 expression.

Based on this knowledge, CVB3-induced autophagosome formation was identified as a potential mechanism for HCN4 aggregation in the cytoplasm (Figure 1). Analysis of autophagosome markers (LC3, Becline-1 and p62) by immunofluorescent imaging confirmed a significantly increased signal intensity for these markers when CVB3 was induced. Additionally, the autophagosome makers and HCN4 showed an elevated colocalization compared to the non-induced group, supporting a possible incorporation of HCN4 into autophagosomes under CVB3 induction.

The Rab7 GTPase plays a major role in transport of autophagosomes [30] and might therefore represent a pharmacological target for the CVB3 mechanism of infection. Addressing this idea, the authors transfected HeLa cells with HCN4-GFP and CVB3 proteins 2C and 3A (dsRed) to analyze colocalization with Rab7 and LC3. Colocalization of Rab7 and LC3 was significantly increased under CVB3-2C and CVB3-3A induction, confirming autophagy induction by CVB3 proteins. Additionally, HCN4 colocalization with Rab7 increased significantly when coexpressed with CVB3-2C, yet highly significant when coexpressed with CVB3-3A. Interestingly, HCN4 colocalization with the autophagosome marker LC3 was only increased when coexpressed with CVB3-3A, but not with CVB3-2C. This might indicate cytoplasmic accumulation of HCN4 by the CVB3 protein CVB3-3A.

Verifying these results, a pharmacological rescue experiment was performed using inhibitors of CVB3-2C (N6-Benzyladenosine, CVB3-3A (GW5074) or Rab7 (CID 196770) to achieve correct reorganization of HCN4 similar to the cell membrane localization under control conditions. Fluorescence intensity of the membranous- and cytosolic fraction of HCN4 was determined after 8 h, 12 h, and 24 h of inhibitor treatment. In contrast to CVB3-2C inhibition, inhibition of either CVB3-3A or Rab7 reorganized HCN4 distribution almost to a standard level after 12 h and 24 h when CVB3-3A was coexpressed. When CVB3-2C was coexpressed, neither CVB3-2C inhibition nor Rab7 inhibition resulted in comparable levels of HCN4 reorganization.

Summarizing these results, the authors concluded a HCN4 localization shift induced by CVB3 infection. Specifically, CVB3-3A was identified as a driver for cytoplasmatic aggregation of HCN4. As CVB3-3A is associated with autophagosome formation and autophagy induction, Peischard et al. focused on autophagosome transport, which includes Rab7 GTPases. Indeed, they found that inhibition of either CVB3-3A or Rab7 rescues HCN4 membrane localization, identifying these as interesting targets for the treatment of virus-induced cardiac disorders (e.g., bradycardia or cardiac arrest) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of HCN4 impairment by Coxsackievirus B3 (CVB3). The cell shown is a pacemaker cell, located in the sinoatrial node (SAN). Expression of CVB3 proteins 2C and/ or 3A inhibits plasma membrane density of HCN4, the major pacemaker channel. Impairment of HCN4 function results in inhibited cardiac pacemaker function in general. This process depends on Rab7-mediated vesicle trafficking, which renders CVB3 proteins 2C and 3A, as well as Rab7, attractive targets for the treatment of cardiac CVB3 infections.

Conclusion

Based on these results, Peischard et al. concluded a HCN4 localization shift induced by CVB3 infection. Specifically, CVB3-3A was identified as the driving force for cytoplasmatic aggregation of HCN4. As CVB3-3A is associated with autophagosome formation and autophagy induction, Peischard et al. focused on autophagosome transport, which is mediated by Rab7 GTPases. Indeed, they found that inhibition of either CVB3-3A or Rab7 rescues HCN4 membrane localization, identifying them as interesting targets for the treatment of virus-induced cardiac disorders (e.g., bradycardia or cardiac arrest) [8].

The relevance of improved treatment for viral diseases has become a global interest due to the pandemic caused by the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. However, the development of antiviral drugs holds fundamental challenges. Viruses generally use the machinery of a host cell for their replication [2,31], resulting in viral protein expression and virus assembly by the host cells [32]. Efficient antiviral drug design therefore requires molecular understanding of viral infection mechanisms. This enables the identification of adjustable target proteins for inhibition of the viral distribution, without causing serious side effects on the host. One option is targeting the virus itself, the other option is targeting host cell components [2]. Cell models build the basis for analysis of cellular and molecular mechanisms in vitro. With improvement of differentiation protocols for hiPSC cultures, it is possible to generate and analyze a variety of cells and tissues.

Screening for antiviral drug targets has previously been dominated by library screenings, infection of cells and protein expression analyses [33,34]. Controllable virus expression by the used cell models enables working on viruses in a highly controlled cellular environment [5]. Moreover, differentiation of hiPSCs allows the analysis of different cell types based on a single cell line. When interested in virus-host-interactions of a specific cell type, specialized models, such as the hiPSC-derived pacemaker-like cells, provide an excellent experimental environment.

Verification of pacemaker function was the basis for subsequent experiments. Expression of HCN4 channels and connexin 45 are fundamental characteristics for pacemaker cells. In addition, electrophysiological analyses provide valid information on the functionality of the differentiated cells [23,35]. Peischard et al. confirmed pacemaker characteristics in their hiPSC-derived pacemaker-like cells, overcoming the previous lack of uniform sample material. In addition to virus-induced HCN4 alteration, viral proteins (CVB3-2C and CVB3-3A) were revealed and parts of the pathophysiological mechanisms of CVB3-3A were elucidated. These findings link CVB3-3A to autophagosomal effects and autophagosome transport with Rab7. Inhibition of either CVB3-3A or Rab7 provides possible targets for treating CVB3-induced bradycardia (Figure 1).

In contrast to the detailed evaluation of the CVB3-3A mechanism, the CVB3-2C effects on HCN4 could not be completely answered. It is currently unknown why inhibition of Rab7 did not rescue HCN4 distribution under CVB3-2C influence, even though Rab7 and HCN4 showed clear colocalization indicating potential functional interactions.

In a literature study on CVB3-2A function, Liu et al. postulated that enteroviral 2C proteins inhibit the NF-κB signaling pathway, resulting in an inhibited immune response [36]. Interestingly, 2C proteins are described as the most conserved non-structural proteins of enteroviruses. Conserved protein structure in enteroviruses could be a key of efficiently treating the genus of enterovirus including enterovirus type 71 (hand, foot, and mouth disease) and CVB3 [37].

Despite the discrepancy between the CVB3-2C hypothesis of Peischard et al. (dysregulated protein transport) and Li et al. (inhibition of immune response), investigation of CVB3-2C seems to be an interesting target, not only for CVB3 infections, but also for enteroviral infections in general [8].

HCN4 describes the major channel responsible for cardiac automaticity [18]. Virus-impacted trafficking in host cell proteins has been documented for CVB3 as well as for SARS-CoV-2 and HIV [20,38,39].

SARS-CoV-2 potentially uses altered trafficking to suppress host cell defenses [38]. Viral replication consists of four phases: entering the target cell, replication of the genome, expression of viral proteins, assembly, and particle release. Viral particle release results in infection of surrounding cells [40]. Since CVB3 exclusively dysregulated HCN4, its impairment could be assumed to provide benefits for CVB3 distribution. The relevance of HCN4 dysregulation requires further research.

In summary, the recent research by Peischard et al. [8] enables host cell-specific characterization of CVB3 infections in pacemaker-like cells. On the one hand, this solves the lack of sample material for human pacemaker cells and, on the other hand, creating a controlled environment for the analysis of virus-host-cell interaction. HCN4 dysfunction has been associated with bradycardia and cardiac arrest [20-22]. However, possible effects of viral infection have never been investigated. Thus, the findings by Peischard et al. reveal new potential targets for CVB3 treatment and drug development. Transferring these results on other (cardiogenic) viruses, as well as to additional cardiac ion channels, may substantially benefit research in the field of cardiology-associated viral diseases.

List of Abbreviations

CVB3: Coxsackievirus B3; DCM: Dilated Cardiomyopathy; hiPSC: Human induced Pluripotent Stem Cells; FACS: Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting; HCN4: Hyperpolarization-activated Cyclic Nucleotide-gated channel 4; MEA: Multi-Electrode Array; TEVC: Two Electrode Voltage Clamp; SAN: Sinoatrial Node

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) Grant numbers DFG Se1077/13-1, FOR 5146-Projektnummer 436298031 and GRK 2515, Chemical biology of ion channels (ChemBion) to GS.

Authors' contributions

LM: Main contributor in writing the comment; NSS: Proofreading; GS: Corresponding author; SP: Corresponding author

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

References

2. Kausar S, Said Khan F, Ishaq Mujeeb Ur Rehman M, Akram M, Riaz M, Rasool G, et al. A review: Mechanism of action of antiviral drugs. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2021;35:20587384211002621.

3. Tian L, Yang Y, Li C, Chen J, Li Z, Li X, et al. The cytotoxicity of coxsackievirus B3 is associated with a blockage of autophagic flux mediated by reduced syntaxin 17 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(2):242.

4. Garmaroudi FS, Marchant D, Hendry R, Luo H, Yang D, Ye X, et al. Coxsackievirus B3 replication and pathogenesis. Future Microbiol. 2015;10(4):629-53.

5. Peischard S, Ho HT, Piccini I, Strutz-Seebohm N, Röpke A, Liashkovich I, et al. The first versatile human iPSC-based model of ectopic virus induction allows new insights in RNA-virus disease. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):16804.

6. Pollack A, Kontorovich AR, Fuster V, Dec GW. Viral myocarditis--diagnosis, treatment options, and current controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(11):670-80.

7. Peischard S, Ho HT, Theiss C, Strutz-Seebohm N, Seebohm G. A Kidnapping Story: How Coxsackievirus B3 and Its Host Cell Interact. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2019;53(1):121-40.

8. Peischard S, Möller M, Disse P, Ho HT, Verkerk AO, Strutz-Seebohm N, et al. Virus-induced inhibition of cardiac pacemaker channel HCN4 triggers bradycardia in human-induced stem cell system. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022;79(8):440.

9. Unudurthi SD, Wolf RM, Hund TJ. Role of sinoatrial node architecture in maintaining a balanced source-sink relationship and synchronous cardiac pacemaking. Front Physiol. 2014;5:446.

10. Amin AS, Pinto YM, Wilde AAM. Long QT syndrome: beyond the causal mutation. J Physiol. 2013;591(17):4125-39.

11. Marbán E. Cardiac channelopathies. Nature. 2002;415(6868):213-8.

12. Riordan JR, Rommens JM, Kerem B, Alon N, Rozmahel R, Grzelczak Z, et al. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science. 1989;245(4922):1066-73.

13. Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Ureche ON, Henrion U, Baltaev R, Mack AF, et al. Long QT syndrome-associated mutations in KCNQ1 and KCNE1 subunits disrupt normal endosomal recycling of IKs channels. Circ Res. 2008;103(12):1451-7.

14. Möller M, Silbernagel N, Wrobel E, Stallmayer B, Amedonu E, Rinné S. et al. In Vitro Analyses of Novel HCN4 Gene Mutations. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49(3):1238-48.

15. Zhang Y, Wang K, Yu Z. Drug Development in Channelopathies: Allosteric Modulation of Ligand-Gated and Voltage-Gated Ion Channels. J Med Chem. 2020;63(24):15258-78.

16. Seebohm G, Strutz-Seebohm N, Baltaev R, Korniychuk G, Knirsch M, Engel J, et al. Regulation of KCNQ4 potassium channel prepulse dependence and current amplitude by SGK1 in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2005;16(4-6):255-62.

17. Muir P. The association of enteroviruses with chronic heart disease. Rev Med Virol. 1992;2(1):9-18.

18. Porro A, Thiel G, Moroni A, Saponaro A. cyclic AMP Regulation and Its Command in the Pacemaker Channel HCN4. Front Physiol. 2020;11:771.

19. Bucchi A, Barbuti A, DiFrancesco D, Baruscotti M. Funny Current and Cardiac Rhythm: Insights from HCN Knockout and Transgenic Mouse Models. Front Physiol. 2012;3:240.

20. Steinke K, Sachse F, Ettischer N, Strutz-Seebohm N, Henrion U, Rohrbeck M, et al. Coxsackievirus B3 modulates cardiac ion channels. FASEB J. 2013;27(10):4108-21.

21. DiFrancesco D. HCN4, Sinus Bradycardia and Atrial Fibrillation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2015;4(1):9-13.

22. Baruscotti M, Bucchi A, Viscomi C, Mandelli G, Consalez G, Gnecchi-Rusconi T, et al. Deep bradycardia and heart block caused by inducible cardiac-specific knockout of the pacemaker channel gene Hcn4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(4):1705-10.

23. Schweizer PA, Darche FF, Ullrich ND, Geschwill P, Greber B, Rivinius R, et al. Subtype-specific differentiation of cardiac pacemaker cell clusters from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2017;8(1):229.

24. Peischard S, Piccini I, Strutz-Seebohm N, Greber B, Seebohm G. From iPSC towards cardiac tissue-a road under construction. Pflugers Arch. 2017;469(10):1233-43.

25. Zhang M, Schulte JS, Heinick A, Piccini I, Rao J, Quaranta R, et al. Universal cardiac induction of human pluripotent stem cells in two and three-dimensional formats: implications for in vitro maturation. Stem Cells. 2015;33(5):1456-69.

26. Boyett MR, Inada S, Yoo S, Li J, Liu J, Tellez J, et al. Connexins in the sinoatrial and atrioventricular nodes. Adv Cardiol. 2006;42:175-97.

27. Massilamany C, Gangaplara A, Reddy J. Intricacies of cardiac damage in coxsackievirus B3 infection: implications for therapy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;177(2):330-9.

28. Alirezaei M, Flynn CT, Wood MR, Harkins S, Whitton JL. Coxsackievirus can exploit LC3 in both autophagy-dependent and -independent manners in vivo. Autophagy. 2015;11(8):1389-407.

29. Wong J, Zhang J, Si X, Gao G, Mao I, McManus BM, et al. Autophagosome supports coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J Virol. 2008;82(18):9143-53.

30. Kuchitsu Y, Fukuda M. Revisiting Rab7 Functions in Mammalian Autophagy: Rab7 Knockout Studies. Cells 2018;7(11).

31. Ho HT, Peischard S, Strutz-Seebohm N, Klingel K, Seebohm G. Myocardial Damage by SARS-CoV-2: Emerging Mechanisms and Therapies. Viruses 2021;13(9):1880.

32. Ryu W-S. Virus Life Cycle. In: Molecular Virology of Human Pathogenic Viruses. Elsevier; 2017. p. 31-45.

33. Kolokoltsov AA, Deniger D, Fleming EH, Roberts NJ, Karpilow JM, Davey RA. Small interfering RNA profiling reveals key role of clathrin-mediated endocytosis and early endosome formation for infection by respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol. 2007;81(14):7786-800.

34. Kolokoltsov AA, Saeed MF, Freiberg AN, Holbrook MR, Davey RA. Identification of novel cellular targets for therapeutic intervention against Ebola virus infection by siRNA screening. Drug Dev Res. 2009;70(4):255-65.

35. Husse B, Franz W-M. Generation of cardiac pacemaker cells by programming and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863(7 Pt B):1948-52.

36. Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S-C. NF-κB signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023.

37. Li Q, Zheng Z, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Liu Q, Meng J, et al. 2C Proteins of Enteroviruses Suppress IKKβ Phosphorylation by Recruiting Protein Phosphatase 1. J Virol. 2016;90(10):5141-51.

38. Banerjee AK, Blanco MR, Bruce EA, Honson DD, Chen LM, Chow A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Disrupts Splicing, Translation, and Protein Trafficking to Suppress Host Defenses. Cell. 2020;183(5):1325-1339.e21.

39. Pereira EA, daSilva LLP. HIV-1 Nef: Taking Control of Protein Trafficking. Traffic. 2016;17(9):976-96.

40. Jones JE, Le Sage V, Lakdawala SS. Viral and host heterogeneity and their effects on the viral life cycle. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021;19(4):272-82.