Abstract

Introduction: Histones play vital roles in gene transcription and chromatin functioning, but they are very harmful since, in intercellular space, they stimulate toxic responses and systemic inflammation. Myelin basic protein (MBP) is the most important protein of the axon myelin-proteolipid sheath. Antibodies with various catalytic activities (abzymes; Abzs) are very specific features of some autoimmune diseases.

Methods: IgGs against individual histones (H3, H1, H2A, H2B, and H4) and MBP were isolated from the blood plasma of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE)-prone C57BL/6 mice by several affinity chromatographies. These IgGs corresponded to different stages of EAE evolution: spontaneous, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG), and complex of DNA with histones accelerated onset, acute, and remission stages.

Results: IgG-Abzs against MBP and five individual histones showed unusual complexation polyreactivity and enzymatic cross-reactivity in the specific hydrolysis of H3 histone. All IgGs at zero time (3-month-old mice) against MBP and five individual histones according to MALDI mass spectrometry demonstrated from 5 to 21 different H3 hydrolysis sites. The spontaneous evolution of EAE during 60 days results depending on IgGs against various histones in a powerful increase or decrease in the type and number of H3 hydrolysis sites. Mice treatment with MOG or DNA-histones complex leads to changes in IgGs activities and a specific alteration in type and number of H3 hydrolysis sites in comparison with sites corresponding to zero time and spontaneous development of EAE. The minimum number (5) of different H3 hydrolysis sites was revealed for IgGs against ?4 (60 days after immunization of mice with DNA-histones complex), while the maximum (21) to IgGs against H1 and MBP (60 days after spontaneous EAE development).

Conclusion: It first was shown that at various stages of EAE development and mice immunization with different antigens, IgG-abzymes against five individual histones and MBP could significantly differ in relative specific activities and number and type of particular sites of H3 hydrolysis. Possible reasons for such catalytic cross-reactivity and strong differences in the type and number of the splitting sites are discussed.

Keywords

EAE mouse model of human multiple sclerosis, C57BL/6 mice, Immunization mice with myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) and DNA-histones complex, Catalytic IgGs, Hydrolysis of histones and myelin basic protein, Cross-complexation and catalytic cross-reactivity

Abbreviations

Abs: Antibodies; AGDs: Antigenic Determinants; Abz: Abzyme; AA: Amino Acid; AIDs: Autoimmune Diseases; BFU-E: Erythroid Burst-Forming Unit (early erythroid colonies); CFU-GM: Granulocytic-Macrophagic Colony-Forming Unit; CFU-E: Erythroid Burst-Forming Unit (late erythroid colonies); CFU-GEMM: Granulocytic-Erythroid-Megakaryocytic-Macrophagic Colony-Forming Unit; EAE: Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis; ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; MBP: Myelin Basic Protein; MOG: Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein; MS: Multiple Sclerosis; HIV-1: Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1; MALDI-TOF: Matrix-Assisted Laser Ionization/Desorption Times-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry; RA: Relative Activity; SLE: Systemic Lupus Erythematosus; SDS-PAGE: Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate–Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis

Introduction

Histones, with their various modified forms, are vitally important in chromatin functioning. However, free extracellular histone molecules in biological liquids usually act as damage factors [1]. Mice treatment with exogenous histones determines several toxic responses because of inflammatory reactions and activation of Toll-like receptors [1]. Mice treatment using antibodies (Abs) neutralizing histones, heparin, activated protein C, and thrombomodulin causes the mice protection against lethal endotoxemia, sepsis, trauma, ischemia-reperfusion injury, pancreatitis, peritonitis, stroke, coagulation, and thrombosis. The increase in the free histones and nucleosome fragments in the biological liquids leads to several pathophysiological processes, including different autoimmune diseases (AIDs), inflammatory processes progression, and cancer [1].

In the core of nucleosome particles, tetramers contain two molecules of H4 and H3 histones circled by two dimers of H2A and H2B interacting with two supercoiled turns of double-stranded DNAs [2]. Histone H3 is important in the emerging field of epigenetics since its sequence variants and variable modifications could play an important role in the dynamic and long-term regulation of genes. H1 histone is essential for the higher-order chromatin substructure packing.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory-demyelinating AID of the central nervous system [3]. It demonstrates large T lymphocytes and macrophages in perivascular infiltration [4]. The activated myelin-reactive CD4+ T cells could be the principal MS mediators [4]. Some data indicate in MS pathogenesis the important role of B cells and auto-Abs against autoantigens of myelin, including MBP [4,5].

Artificial catalytically active antibodies (abzymes) against stable analogues of transition states of chemical reactions and their use [6-13], as well as natural abzymes, are well described in the literature [14-22].

There are several experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) mice models, which well mimic human MS-specific facets (for review, see [23-28]). AIDs were first suspected might be originated from particular defects of bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) [29]. Later, it was demonstrated that the spontaneous and antigen-accelerated evolution of AIDs occurs because of the specific reorganization of bone marrow HSCs [30-34]. EAE-prone C57BL/6 and SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus)-prone MRL-lpr/lpr mice were used for the analysis of possible mechanisms of spontaneous and antigen-accelerated AIDs [30-34]. It was shown that immunization of SLE-prone mice with DNA-proteins complexes and C57BL/6 mice with DNA-histones complexes or MOG [30-34] causes a significant acceleration of these AIDs development. The acceleration of AIDs is conditioned by particular specific changes in HSC differentiation profiles together with a significant rise in lymphocyte proliferation and repression of cells apoptosis in different organs of mice [30-34]. Moreover, these specific changes are associated with the appearance of many different auto-Abs-abzymes degrading DNAs, RNAs, polysaccharides, peptides, and proteins. The detection of various auto-Abzs is the earliest and statistically significant marker of the onset of many AIDs [30-34]. Catalytic activities of Abzs are easily detected even at the onset of several autoimmune pathologies (the pre-disease stage or the beginning of AIDs) before discovering typical markers of different AIDs [30-34]. Titers of auto-Abs to specific auto-antigens at the beginning of many AIDs usually correspond to typical indices' ranges characterizing healthy individuals. The appearance of plural Abzs legibly indicates the start of autoimmune reactions; an elevation in enzymatic activities of Abzs is associated with the achievement of profound pathologies [30-34]. However, several parallel mechanisms could provide different AIDs development, usually leading to self-tolerance breakdown [30-34].

Natural auto-Abzs degrading various peptides, proteins, oligosaccharides, nucleotides, DNAs, and RNAs were found in the blood sera of patients with several AIDs [33-46]. Conditionally healthy humans usually lack abzymes [30-34]. Auto-abzymes with very low activities degrading polysaccharides [35], vasoactive neuropeptide [36], and thyroglobulin [37,38] were, however, found in the blood of some healthy volunteers. The blood of SLE and MS patients contains Abzs hydrolyzing, RNAs, myelin basic protein (MBP), oligosaccharides, and histones [30-34].

Abzymes hydrolyzing five histones and MBP are of particular interest for understanding the mechanisms of AIDs and especially MS development. Abzs degrading five histones (H1-H4) and MBP are revealed in sera of MS [42], HIV-infected patients [34], and EAE-prone mice [43-46].

Detailed studies of abzymes showed that the immune response to auto-antigen in AIDs is very complex and multifaceted than could be imagined based on classical immunology. It was demonstrated recently that auto-IgGs of HIV-infected and MS patients against MBP hydrolyze specifically MBP and five H1-H4 histones and vice versa – preparations of abzymes against five histones effectively cleavage MBP [30,31,33,34]. It was wondering whether this catalytic cross-reactivity phenomenon is common for humans and animals with different AIDs. Recently, IgGs against five histones and MBP corresponding to spontaneous, DNA-histones complex, and MOG accelerated onset, acute, and remission stages of C57BL/6 mice EAE achievement were analyzed [43-46]. Such IgG-abzymes against five histones and MBP possess unusual polyreactivity in complex formation and catalytic cross-reactivity in the hydrolysis of H1, H2A, H2B, H4 histones, and MBP.

It was important to understand whether there is an unusual enzymatic cross-reactivity of Abs-Abzs against MBP and histones only in the case of H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones or for H3 histone also. In addition, the study of Abzs at different stages of EAE achievement by C57BL/6 mice allows us to understand how the relative activity of Abzs and their sequence specificity with respect to MBP and H3 histone can be changed depending on the stage of pathology.

Therefore, here we purified not only preparations of total polyclonal IgGs against five histones but also isolated Abs against five individual histones and MBP corresponding to different stages of EAE development. Then, we analyzed the Abs relative catalytic activity and catalytic cross-reactivity of IgGs against each of the five individual histones and MBP in the hydrolysis of H3 histone for the first time. It was demonstrated that Abzs against MBP and every of five histones possess catalytic cross-reactivity in the hydrolysis of H3 histone. In addition, IgGs against each of the five histones (H1-H4) and MBP corresponding to different stages of EAE development hydrolyze H3 histone in various specific sites and with different efficiency. Such chimeric abzymes with cross-catalytic reactivity could be very hazardous for the achievement of many AIDs since Abzs against five histones can damage MBP of nerve tissue shells.

Methods

Materials and chemicals

All compounds used, an equimolar mixture of H1-H4 five histones and individual homogeneous H3 histone were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein G-Sepharose and Superdex 200 columns were purchased from GE Healthcare (New York, USA). Myelin basic protein (MBP) was from the DBRC (Center of Molecular Diagnostics - Therapy; Moscow, Russia). Affinity sorbents containing immobilized histones (total or individual) and MOG were obtained according to the manufacturer's protocol using BrCN-activated Sepharose (Sigma; St. Louis, MO, USA), the mixture of five H1-H4 histones or five individual histones or MBP. Mouse MOG [35-55] oligopeptide was purchased from EZBiolab (Heidelberg, Germany). All preparations used were free from any possible contaminants.

Experimental animals

3-month-old C57BL/6 inbred mice (zero time of the experiment) were used recently to analyze possible mechanisms of spontaneous or antigen-induced development of EAE [43-46]. They were grown in special conditions free of pathogens in the vivarium of the ICG (Institute of Cytology and Genetics). All experiments with EAE-prone C57BL/6 mice were supported by the Bioethical Committee of the ICG protocols (document number - 134A of 07 September 2010), according to the principles of European Communities Council Directive: 86/609/CEE concerning experiments with animals. This Committee of the Institute supported the study. The weights, titers of antibodies against five histones and MBP, the - proteinuria (concentration of proteins in urine, mg/mL), and some other indexes characterizing EAE development were analyzed and described in [30-34,43-46].

Antibody purification

Polyclonal IgGs samples from the blood plasma of EAE-prone C57BL/6 mice (electrophoretically homogeneous) were isolated first by blood plasma proteins affinity chromatography on Protein G-Sepharose. Then, IgGs preparations were additionally subjected to FPLC (fast protein liquid chromatography-gel filtration) on Superdex-200 HR 10/30 column [43-46]. For additional purification of IgGs after their gel filtration, central parts of Abs peaks were filtrated through filters (pore size 0.1 µm) as in [43-46].

Removal of all IgGs-Abzs against H1-H4 five histones from total polyclonal IgG preparations was performed using histone5His-Sepharose (5.0 ml) containing five immobilized H1-H4 histones. The histone5His-Sepharose column was equilibrated with buffer A (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). After Abs loading, the column was washed carefully with A buffer to zero optical density (A280). Adsorbed IgGs possessing a low affinity for five immobilized histones were eluted from the column using A buffer supplemented with NaCl (0.2 M). High affinity for the histones IgGs were then desorbed specifically from the sorbent using an acidic buffer (0.1 M glycine-HCl, pH 2.6). The IgGs fractions eluted from the histone5His-Sepharose column at loading, and the sorbent washing with buffer A (5.0 mL) were unified and used to purify IgGs against MBP by their chromatography on the 5 mL MBP-Sepharose column equilibrated with buffer A. After the MBP-Sepharose washing with A buffer to zero optical density (A280), adsorbed low affinity for MBP IgGs were eluted first by buffer A and then with the same buffer supplemented with NaCl (0.2 M). Then, anti-MBP Abs were eluted from the affinity sorbent using acidic Tris-Gly buffer (pH = 2.6), similar to histone5His-Sepharose. Then, this fraction of IgGs preparation was named and used as anti-MBP antibodies. Such IgGs preparations were isolated in the case of mice corresponding to various stages before (Con-aMBP-0d, Spont-aMBP-60d) and after mice treatment with DNA-histones complex (DNA20-aMBP and DNA60-aMBP) and MOG (MOG20-aMBP) (Table 1).

|

|

Different total IgGs |

Designation |

IgGs against individual histones |

Designation |

|

Zero time (control), beginning of experiments (3 mice-old mice) |

Zero time (control) beginning of the experiment, IgGs against 5 histones and MBP |

Con-aH1-H4-0d |

anti-H1 histone |

Con-aH1-0d |

|

anti-H2A histone |

Con-aH2A-0d |

|||

|

anti-H2B histone |

Con-aH2B-0d |

|||

|

Con-aMBP-0d |

anti-H3 histone |

Con-aH3-0d |

||

|

anti-H4 histone |

Con-aH4-0d |

|||

|

Spontaneous development of EAE during 60 days (without mice immunization at 3 mice of age)

|

Spontaneous (spont) development of EAE during 60 days; IgGs against 5 histones and MBP |

Spont-aH1-H4-60d |

anti-H1 histone |

Spont-aH1-60d |

|

anti-H2A histone |

Spont-aH2A-60d |

|||

|

anti-H2B histone |

Spont-aH2B-60d |

|||

|

Spont-aMBP-60d |

anti-H3 histone |

Spont-aH3-60d |

||

|

anti-H4 histone |

Spont-aH4-60d |

|||

|

IgGs corresponding to 20 days after mice immunization with MOG |

IgGs against 5 histones and MBP corresponding to 20 days after mice immunization with MOG |

MOG20- aH1-H4-20 |

anti-H1 histone |

MOG20-aH1 |

|

anti-H2A histone |

MOG20-aH2A |

|||

|

anti-H2B histone |

MOG20-aH2B |

|||

|

MOG20- aMBP |

anti-H3 histone |

MOG20-aH3 |

||

|

anti-H4 histone |

MOG20-aH4 |

|||

|

IgGs corresponding to 20 days after mice immunization with complex DNA-histones |

IgGs against five histones and MBP; 20 days after mice immunization with complex DNA-histones |

DNA20- aH1-H4 |

anti-H1 histone |

DNA20-aH1 |

|

anti-H2A histone |

DNA20-aH2A |

|||

|

anti-H2B histone |

DNA20-aH2B |

|||

|

DNA20- aMBP |

anti-H3 histone |

DNA20-aH3 |

||

|

anti-H4 histone |

DNA20-aH4 |

|||

|

IgGs corresponding to 60 days after mice immunization with complex DNA-histones |

IgGs against five histones and MBP; 60 days after mice immunization with complex DNA-histones |

DNA60- aH1-H4 |

anti-H1 histone |

DNA60-aH1 |

|

anti-H2A histone |

DNA60-aH2A |

|||

|

anti-H2B histone |

DNA60-aH2B |

|||

|

DNA60- aMBP |

anti-H3 histone |

DNA60-aH3 |

||

|

anti-H4 histone |

DNA60-aH4 |

|||

|

*All these IgG preparations were used for the analysis of H3 histone hydrolysis. |

||||

For additional purifications of IgGs against 5 histones from possible hypothetical impurities of antibodies against MBP, the fractions eluted from histone5His-Sepharose were subjected to re-chromatography on MBP-Sepharose. IgGs eluted at the loading on MBP-Sepharose were named anti-5-histones IgGs. IgGs against 5 histones were separated from the blood plasma of mice corresponding to different stages of development of EAE before (Con-aH1-H4-0d, Spont-aH1-H4-60d), after immunization of mice with MOG (MOG20-aH1-H4-20) and DNA-histones complex (DNA20- aH1-H4 and DNA60- aH1-H4) (Table 1).

Antibody purification against individual five histones

IgG preparations against H1-H4 five histones were used further to isolate IgGs preparations against each of the five individual histones. The Abs preparations were applied sequentially first on H3-Sepharose containing immobilized H3. The fractions of IgGs eluted at loading on this resin were then applied sequentially to the following four sorbents: H1-Sepharose, H2A-Sepharose, H2B-Sepharose, and H4-Sepharose. All affinity chromatographies were carried out as in the case of MBP-Sepharose and histone5His-Sepharose. IgGs against H3, H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones were specifically eluted from each of the five affinity sorbents using buffer, pH 2.6 [43-46]. These IgGs fractions were designated respectively as anti-H3, anti-H1, anti-H2A, anti-H2B, and anti-H4 IgGs with the indicating to which EAE stage and which antigen used they correspond: Con (onset of the experiment); Spont (60 days of spontaneous EAE development); MBP (20 days after mice treated with MOG); DNA (20 or 60 days after mice treated with DNA-histones complex) (Table 1).

Proteolytic activity assay

Protease activity of all IgGs-Abzs was analyzed using SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis). The reaction mixtures (10–15 mL) containing 20 mM buffer Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1.0 mg/mL MBP, a mixture of five histones, or H3 histone, and 0.012 mg/mL IgGs preparations against histones or MBP (0.07-0.1 mg/mL) as described in [43-46]. The mixtures of histones or MBP and IgGs were incubated during 3–14 h at 37° C. The reactions of H3 hydrolysis were stopped by the addition of SDS to the 0.1% final concentration. The efficiency of H3 and MBP splitting was analyzed by SDS-PAGE using 20% gels. The gels were colored silver or Coomassie Blue. The relative proteolytic activities of IgGs preparations were calculated from the decrease in relative intensity of protein bands corresponding to initial non-hydrolyzed H3 or MBP corresponding to these protein-substrates incubation without IgGs. A detailed analysis of H3 hydrolysis sites by IgGs was performed using the MALDI-TOF spectrometry method.

MALDI-TOF analysis of histone hydrolysis

H3 histone was hydrolyzed for 0-20 h in the presence of IgGs preparations against MBP or five individual histones using standard conditions described above. The ascertainment of the H3 hydrolysis products was performed using the 337-nm nitrogen laser VSL-337 ND, 3 ns pulse duration of Reflex III system (Bruker Frankfurt, Germany). Aliquots of reaction mixtures (1–2 µL) incubated at 23oC during different times (0-20 h) were used for analysis by MALDI mass spectrometry. As the matrix, sinapinic acid was used. To 1.6 µl of the matrixes and 1.6 µL of 0.2% trifluoroacetic acid, 1.6 µL of the solutions containing histone H3 (1.0 mg/mL) were added, and 1.0-1.6 µL of the mixtures obtained were applied on the iron MALDI plates. They were air-dried. All MALDI spectra obtained were calibrated using special standards II and I calibrant mixtures of special oligopeptides or proteins (Germany, Bruker Daltonic) in the external as well as internal calibration mode. The analysis of molecular weights (Da) and specific sites of H3 hydrolysis by different IgGs preparations was performed using Protein Calculator v3.3 (Scripps Research Institute).

Statistical analysis

The results correspond to the average values (mean ± standard deviation) from 9-10 independent MALDI spectra for each IgGs preparation against 5 individual histones and MBP.

Results

Choosing a model for analysis of IgGs enzymatic cross-reactivity

Theoretically, the immune system of humans can produce up to 106 variants of Abs against one antigen with different properties [30-34]. The possibilities of enzyme immunoassay (ELISA) and affinity chromatography in studying the possible diversity of antibodies in the sera blood of healthy donors and patients with AIDs against external and internal specific antigens are minimal.

As was shown in many publications (for review, see [30-34,41-46]), only the analysis of the catalytic activities of antibodies allows the revealing of an exceptionally expanded diversity of antibodies against different individual antigens. An approximate evaluation of the possible number of abzymes for one antigen and their diversity in terms of enzymatic properties was carried out in several works [30-34,41-46]. A cDNA library of light chains (κ-type) of antibodies from SLE patients and the phage display method were used to obtain monoclonal abzymes [47-52]. The pool of phage particles was divided into ten peaks eluted from MBP-Sepharose by different concentrations of NaCl. Phage particles of one peak (0.5 M NaCl) were used to obtain individual colonies and isolation corresponding to these colonies' monoclonal light chains of antibodies (MLChs) [47-52]. MLChs corresponding to 22 out of 72 (~30%) randomly selected of 440 individual colonies possess MBP-hydrolyzing activity. Of the 22 MLCh preparations with a comparable affinity for MBP, 12 had metalloprotease activity, four were serine-like, and three were thiol-like proteases. Two MLChs demonstrated serine and metalloprotease activities combined in one active site and one had three activities - these two proteases and DNase activity [49,52].

It is important that, unlike other antibody analysis methods, determining the optimal conditions for the manifestation of catalytic activity makes it possible to distinguish between antibodies with comparable affinity for the same antigen. It showed that all preparations of MLCh-abzymes differed greatly in relative activity, optimal concentrations of ??different metal ions (K+, Na+, Mg2+, Zn2+, Mn2+, Co2+, Ni2+, etc.), as well as pH optima [49,52].

The DNA sequences of these MLChs were analyzed, and they were identical (89-100%) to the germ lines of IgLV8 light chain genes of several described Abs [47-52]. Homology analysis of the MLChs protein sequences with those of several classical Zn2+- and Ca2+-dependent and human serine and thiol proteases was carried out. The analysis revealed MLChs protein sequences responsible for MBP binding, metal ion chelation, and catalysis. All of them turned out to be very close to those for serine-like and metal-dependent classical proteases [47-52].

It should be emphasized that IgGs of all peaks eluted from MBP-Sepharose had MBP-hydrolyzing activities. If we take into account the average percentage of active abzymes in one of 10 peaks, which is approximately 30%, and the number of analyzed individual colonies, then the possible number of abzymes of only κ–type of light chains with MBP-hydrolyzing activity in the blood of SLE patients can be ≥ 1000. However, the MBP-hydrolyzing activity possessed antibodies with kappa and lambda chains [47-52].

The evolution of EAE in EAE-prone C57BL/6 mice arises spontaneously [23-28,33,34]. Immunization of mice with DNA-histones complexes or MOG significantly accelerates the development of EAE [30,31,33,34]. After mice immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex, there are several stages of the EAE progress: the onset at 7-8, the acute phase at 18-20, and the remission stage later 25-30 days [23-28,33,34]. The acceleration of pathology achievement is associated with specific changes in the profile of bone marrow HSCs differentiation and the increase in lymphocyte proliferation [30-34]. These processes, in parallel, are bound with the production of lymphocytes synthesizing Abzs degrading DNAs, RNAs, MBP, MOG, and histones. The parameters characterizing all these specific changes in mice were investigated earlier in [30,31,33,34]. To analyze the enzymatic cross-reactivity of IgGs, we have chosen two antigens described earlier: C57BL/6 mice immunized with MOG and DNA-histones complex [30,31,33,34,43-46]. Data relating to changes in the differentiation profile of HSCs before and after mice treatment with MOG and DNA-histones complex are presented in Combined Supplementary data (Supplementary Figure S1). Data on the changes in the titers of Abs against DNA, MOG, and histones during the evolution of EAE are given in Supplementary Figure S2. The changes in the relative activities of abzymes in the hydrolysis of MBP, MOG, DNA, and histones during the EAE development are demonstrated in Supplementary Figure S3. One can see that during development of spontaneous EAE, the increment in the relative amounts of four precursors of hemopoietic cells [CFU-E (erythroid burst-forming unit - late erythroid colonies), CFU-GM (granulocytic-macrophagic colony-forming unit), CFU-GEMM (granulocytic-erythroid-megakaryocytic-macrophagic colony-forming unit), and BFU-E (erythroid burst-forming unit early erythroid colonies)] in the bone marrow of C57BL/6 mice are relatively slow and gradual. Mice immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex results in various overtime changes in the profile of stem cells differentiation. Overall, EAE development accelerates in all cases [30,31,33,34,43-46].

Recently, we studied a possible catalytic cross-reactivity of IgGs of C57BL/6 mice against five individual histones (H1-H4, isolated using Sepharose containing five immobilized histones) as well as MBP in the hydrolysis of H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones [43-46]. It was shown that the treatment of mice with MOG and complex DNA with histones results in the hydrolysis of all H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones by specific IgGs against each of five histones (H1-H4) in different sites. Moreover, the sites of every five histones hydrolysis by IgGs against five histones and MBP significantly change depending on the different stages of development of EAE [43-46]. In this work, a detailed analysis of the enzymatic cross-activity of IgGs against five histones and MBP was carried out using the H3 as substrate.

For this purpose, IgGs against each of the five individual histones were isolated from the fraction of antibodies against all five histones. It was shown that the treatment of mice with MOG leads to the onset of the pathology by 7–8 days (the appearance of abzymes) and a sharp worsening in the acute phase at 18–20 days (maximum activity of abzymes). After treatment of mice with a DNA–histones complex, the first peak of EAE development activation is observed in 7–20 days. Still, the activity of abzymes increases more strongly in addition from 30 to 60 days. Thus, the following groups of mice were used to purify and analyze total IgGs against 5 histones, individual histones, and MBP corresponding to different stages of EAE (Table 1).

Purification of antibodies

Purification of electrophoretically homogeneous IgG preparations (IgGmix; the mixtures of 7 plasma blood samples corresponding to each of the mice groups) using Protein G-Sepharose and FPLC gel filtration in drastic conditions (pH 2.6) was described previously [43-46]. After SDS-PAGE of IgGmix samples, proteolytic activity in the hydrolysis of histones and MBP was detected only in one IgG protein band (Supplementary Figure S4).

IgGmix against five histones corresponding to each of the mice groups was purified earlier by chromatography on histone5H-Sepharose containing five immobilized histones [43-46]. Non-specifically bound and having low affinity to five histones, IgG fractions were first eluted with 0.2 M NaCl. Anti-histones specific IgGs having a high affinity for five histones were eluted with Tris-Gly buffer, pH 2.6 [43-46]. For additional purification of IgGs against 5 histones from potential impurities of Abs against MBP, the fraction from histone5H-Sepharose was passed through MBP-Sepharose. The fraction obtained at loading onto MBP-Sepharose was further used as anti-5-histones IgGs and was used to purify IgGs against each of the 5 individual histones (Table 1).

The IgGmix fraction eluted at loading from histone5H-Sepharose was used to isolate anti-MBP IgGs by their chromatography on MBP-Sepharose [43-46]. IgGs with low affinity for MBP-Sepharose were eluted using NaCl (0.2 M). Anti-MBP Abs were eluted using an acidic buffer (pH 2.6) as in [43-46]. For additional removal of anti-MBP IgGs against potential impurities of anti-histones IgGs, the fraction eluted from MBP-Sepharose was subjected to re-chromatography on histone5H-Sepharose. The fraction of IgGs eluted from the histone5H-sorbent was named anti-MBP antibodies (Table 1).

A possible enzymatic cross-reactivity of anti-5-histone IgGs (from histone5-Sepharose) and anti-MBP IgGs (from MBP-Sepharose) was first analyzed. Figures 1A and 1B demonstrate hydrolysis of H3 histone with anti-5-histone IgGs and anti-MBP IgGs, while Figures 1C and 1D show hydrolysis of MBP by these IgGs.

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE analysis of H3 histone splitting by IgGs-Abzs against five histones (A) and H3 histone with antibodies against MBP (B) as well as cleavage myelin basic protein (MBP) by IgGs against five histones (C) and Abs-abzymes against MBP (D). Lanes C correspond to the histones (A and B) and MBP (C and D) incubated in the absence of IgGs. The mixtures of MBP or five histones with (0.03-0.1 mg/ml) and without IgGs were incubated for 12 h. The relative percentage of H3 and MBP hydrolysis was estimated by comparing the relative density of these proteins bands compared to proteins incubated in the absence of antibodies (Lanes C).

The efficiency of H3 and MBP cleavage with IgGs against 5 histones and MBP was estimated from the decrease in these proteins in their initial bands (lanes C, Figure 1) after incubation with IgGs compared to their content after control-incubation of H3 histone without antibodies. After 12 h of H3 incubation with different IgGs, the relative content of H3 (~15.3 kDa) and MBP (~18.5 kDa) decreased remarkably or significantly compared to the control experiment (lanes C). These data suggest that IgGs against five histones and MBP possess the known phenomenon of Abs' unspecific complex formation polyreactivity and enzymatic cross-reactivity in MBP and H3 histone hydrolysis. These data cannot, however, provide monosemantic proof of enzymatic cross-reactivity between IgG-abzymes against MBP and five histones because it cannot be ruled out that after their isolations by several affinity chromatographies, the obtained IgGs nevertheless could contain minimal admixtures of alternative IgGs. More powerful evidence of catalytic cross-reactivity could be achieved from a significant difference in the specific sites of H3 histone hydrolysis by IgGs against MBP and five individual histones.

MALDI specters of H3 histone hydrolysis

Here, the analysis of enzymatic cross-reactivity in the hydrolysis of H3 histone by IgGs against five individual histones and MBP was carried out.

The IgGs fractions possessing a high affinity to five individual histones and MBP were used to reveal the cleavage sites of H3 by MALDI TOF mass spectrometry. First, an analysis of the splitting sites of histone H3 was carried out using IgGs against H3 corresponding to the zero time (3-months-old mice) in comparison with the spontaneous development of EAE (without immunization of mice) within 60 days as well as mice immunization with MOG and complex DNA-histones (Figure 2). Right after the addition of the IgGs (Figure 2A), H3 histone was almost homogeneous, showing 2 signals of its one- (m/z = 15,263.4 Da) and two-charged ions (m/z = 7631.7 Da). For all IgG samples listed in Table 1, 9-10 spectra were obtained. Several typical specters are shown in Figure 2. Each preparation of IgGs demonstrated a specific set of peaks corresponding to products of H3 histone hydrolysis.

Figure 2. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the absence (A) and the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against H3 corresponding Con-aH3-0d (B), Spont-aH3-60d (C), MBP20-aH3 (D), DNA20-aH3 (E), and DNA60-aH3 (F). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

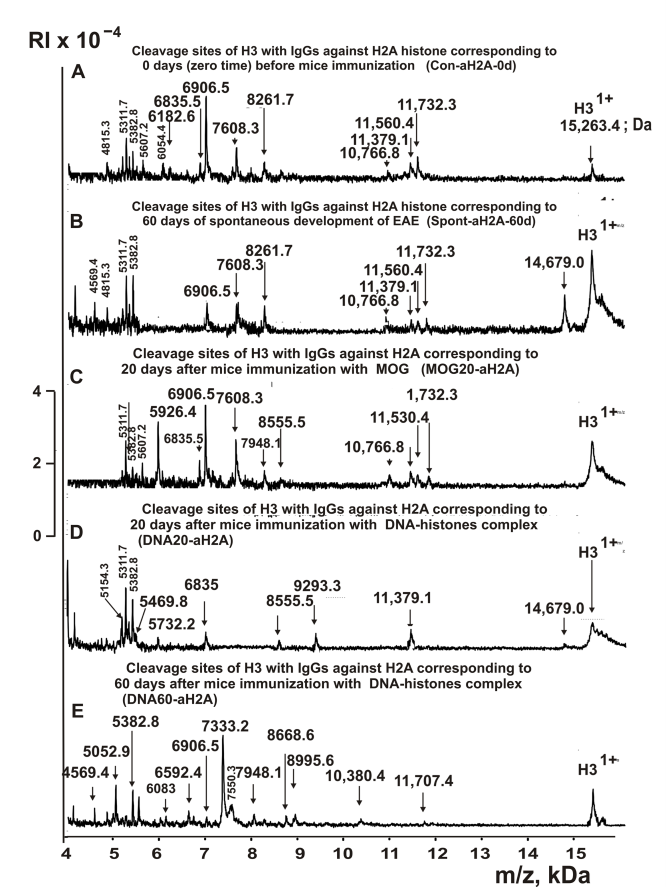

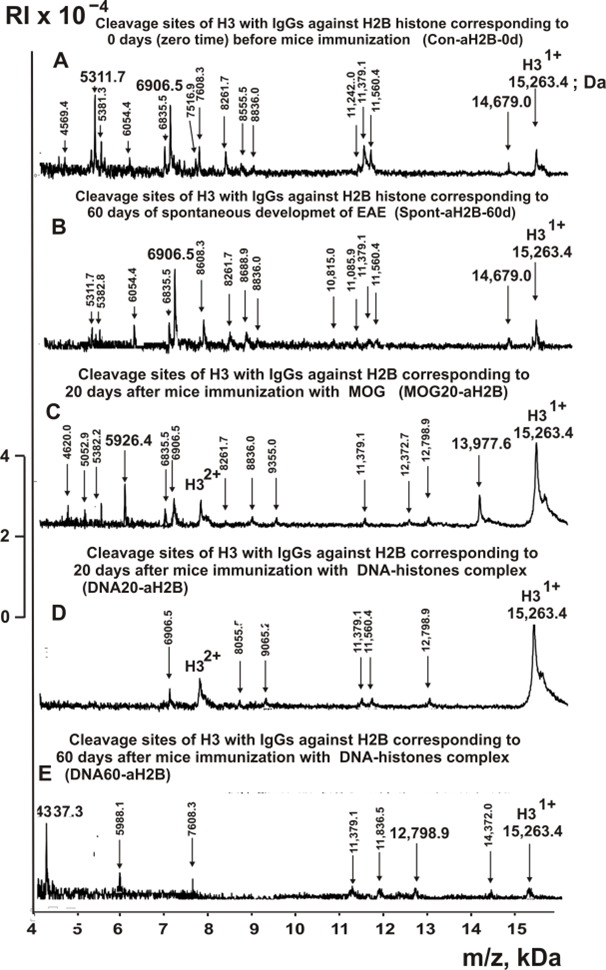

It can be seen that in comparison with the initial experiment (zero time), there is a change in the types and number of sites for hydrolysis of H3 histone by antibodies against this histone after the spontaneous development of EAE for 60 days and immunization of mice with MOG and a complex of DNA with histones. A similar situation was observed in the case of hydrolysis of H3 histone by IgGs against H1, H2A, H2B, and H4, corresponding to different stages of EAE development. Figures 3-5 demonstrate spectra corresponding to hydrolysis of H3 by IgGs against H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones before and after immunization of mice with MOG and the DNA-histones complex.

Figure 3. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against H1 corresponding Con-aH1-0d (A), Spont-aH1-60d (B), MBP20-aH1 (C), DNA20-aH1 (D), and DNA60-aH1 (E). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

Figure 4. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against H2A corresponding Con-aH2A-0d (A), Spont-aH2A-60d (B), MBP20-aH2A (C), DNA20-aH2A (D), and DNA60-aH2A (E). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

Figure 5. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against H2B corresponding Con-aH2B-0d (A), Spont-aH2B-60d (B), MBP20-aH2B (C), DNA20-aH2B (D), and DNA60-aH2B (E). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

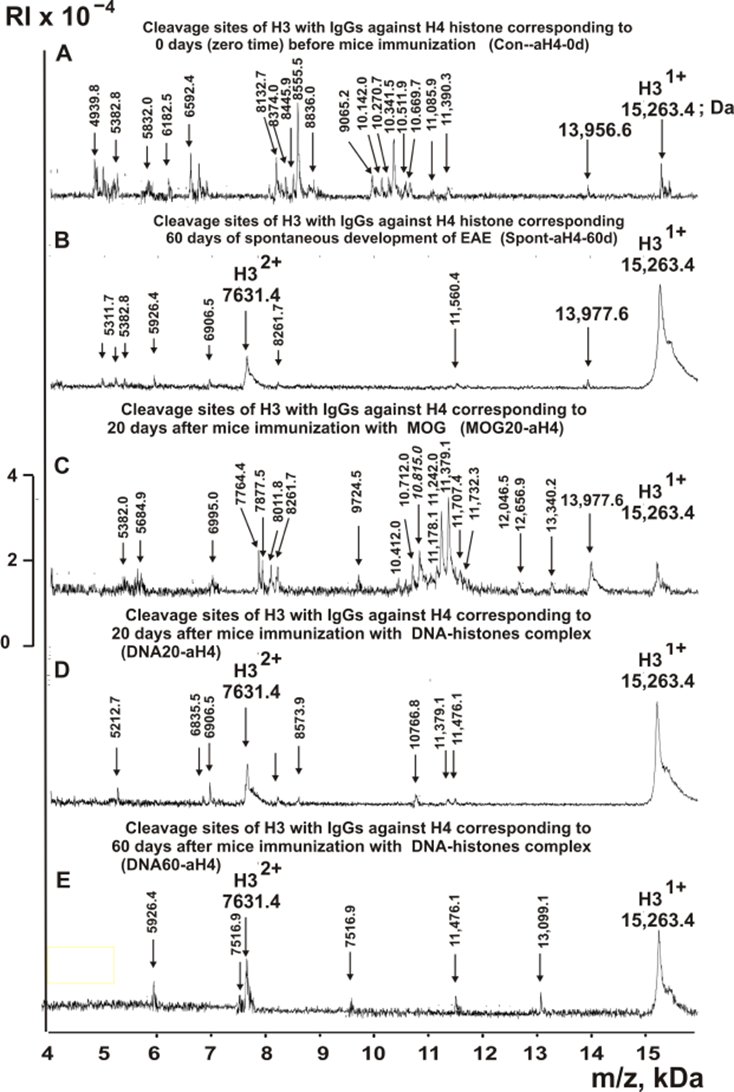

One can see from Figures 2-6 that each IgG preparation demonstrates its specific number of peaks corresponding to hydrolysis H3 histone products with different molecular weights.

Figure 6. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against H4 corresponding Con-aH4-0d (A), Spont-aH4-60d (B), MBP20-aH4 (C), DNA20-aH4 (D), and DNA60-aH4 (E). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

Figure 7 shows specters of H3 histone splitting by IgGs corresponding to IgGs against MBP.

Figure 7. MALDI-TOF spectra corresponding to products of H3 (1.0 mg/ml) hydrolysis in the presence of Abs (0.04 mg/ml) against MBP corresponding Con-aMBP-0d (A), Spont-aMBP-60d (B), MOG20-aMBP (C), DNA20-aMBP (D), and DNA60-aMBP (E). All designations of IgGs and the values of m/z are shown in the Figure.

As can be seen from Figures 2-7, antibodies against all five histones and MBP, corresponding to different stages of EAE development, hydrolyze H3 histone at a different number of sites, which differ in type and location in the protein molecule of H3 histone.

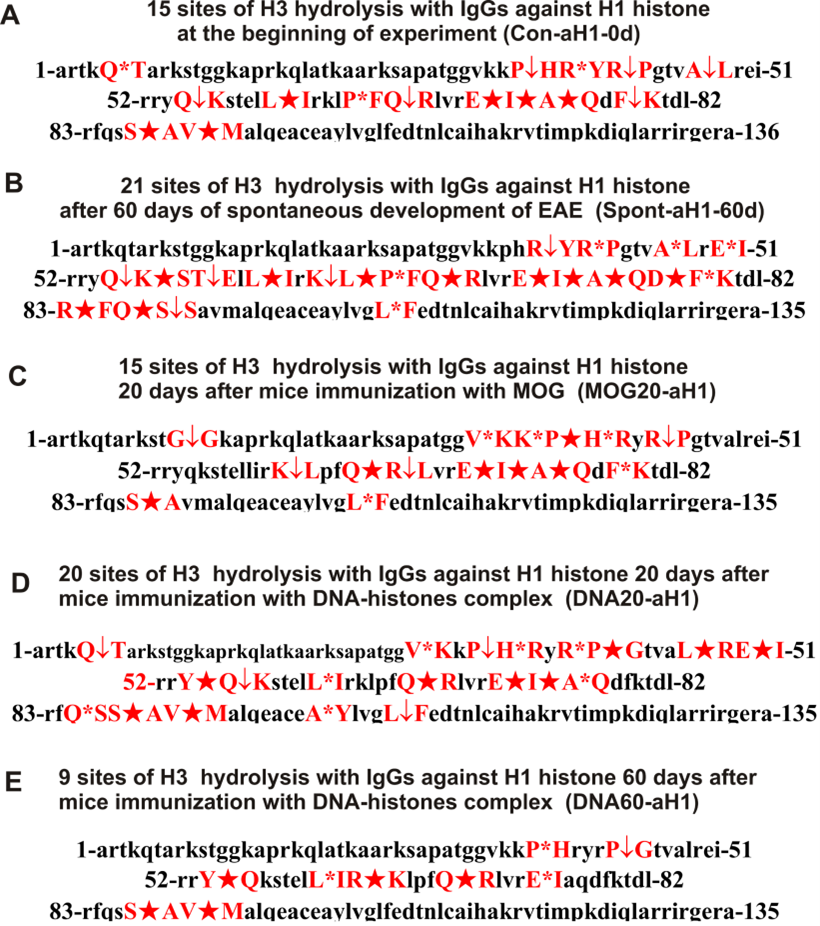

Sites of H3 histone hydrolysis

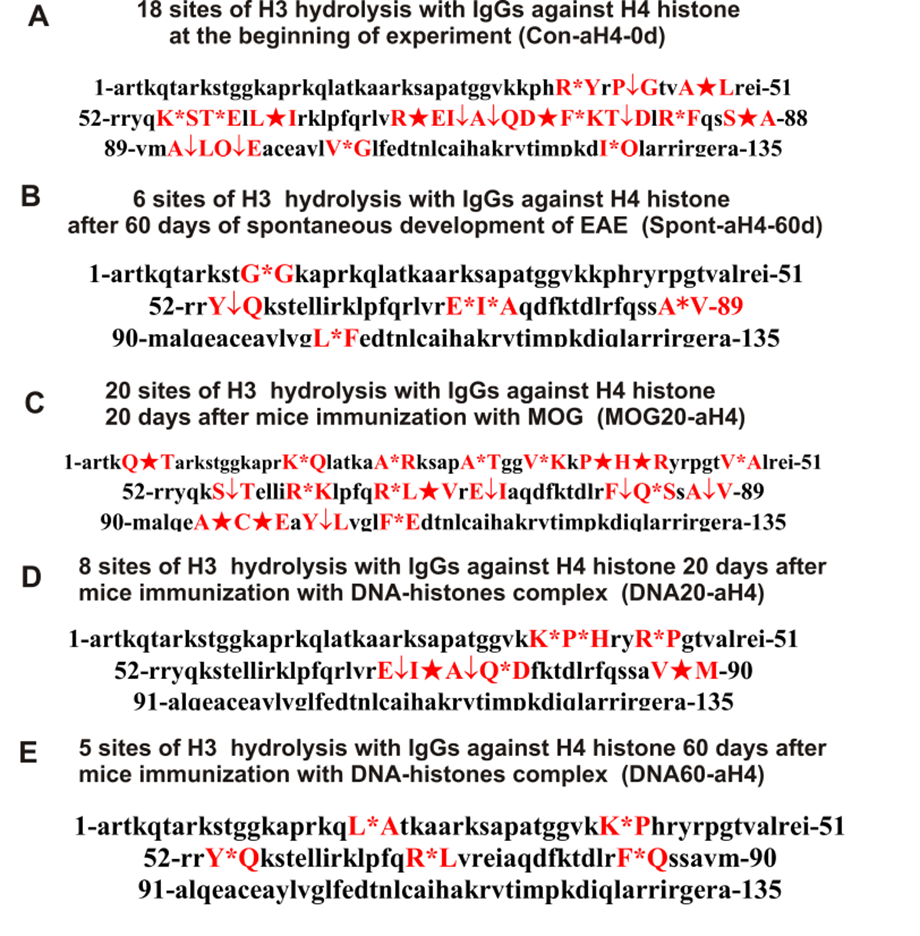

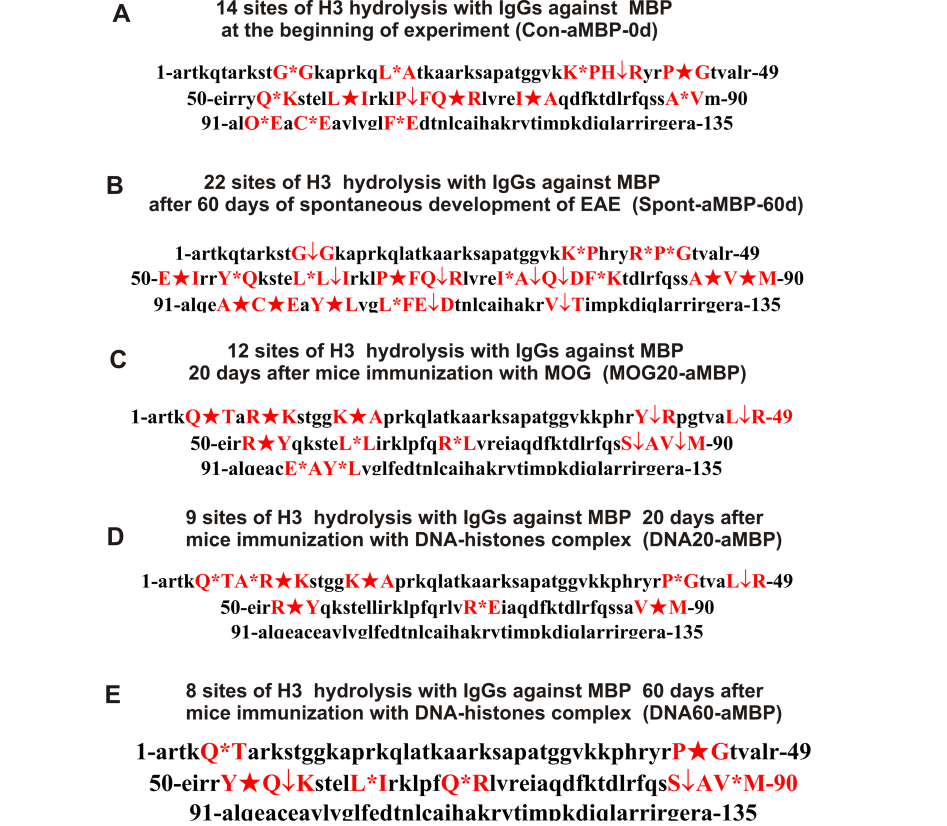

The types of sites of H3 hydrolysis by all IgG preparations were established using an average data of 8-10 independent spectra. All sites of H3 histone hydrolysis by all IgGs against five individual histones and MBP are summarized in Figures 8-13.

Figure 8. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against H3 histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aH3-0d (A); Spont-aH3-60d (B); MOG20-aH3 (C); DNA20-aH3 (D); and DNA60-aH3 (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Figure 9. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against H1 histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aH1-0d (A); Spont-aH1-60d (B); MOG20-aH1 (C); DNA20-aH1 (D); and DNA60-aH1 (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Figure 10. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against H2A histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aH2A-0d (A); Spont-aH2A-60d (B); MOG20-aH2A (C); DNA20-aH2A (D); and DNA60-aH2A (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Figure 11. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against H2B histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aH2B-0d (A); Spont-aH2B-60d (B); MOG20-aH2B (C); DNA20-aH2B (D); and DNA60-aH2B (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Figure 12. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against H4 histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aH4-0d (A); Spont-aH4-60d (B); MOG20-aH4 (C); DNA20-aH4 (D); and DNA60-aH4 (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Figure 13. Sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgG preparations against MBP histone corresponding to 3-month-old mice (zero time), after spontaneous development of EAE (before mice treatment) during 60 days and immunization with MOG and DNA-histones complex: Con-aMBP-0d (A); Spont-aMDP-60d (B); MOG20-aMBP (C); DNA20-aMBP (D); and DNA60-aMDP (E). Major sites of H3 histone cleavage are shown by stars (?), moderate ones by arrows (↓), and minor sites of the cleavages by small stars (*).

Overall, the sites of H3 histone cleavage by IgGs against five histones H1-H4 and MBP corresponding to the beginning of the experiment, spontaneous development of EAE during 60 days, 20 days after mice immunization using MOG, as well as 20 and 60 days after their treatment with DNA-histones complex are substantially, very, or completely different and predominantly are located in specific amino acids (AAs) clusters of different lengths.

Tables with sites of H3 histone hydrolysis

All IgGs preparations split H3 histone in many different sites, various fragments of H3 protein sequence. To facilitate comparison of the different sites of hydrolysis of H3 with IgGs against various histones, they are given in three Tables.

IgGs against H3 histone of 3-months-old mice (zero time, Con-aH3-0d) hydrolyzed this histone at 11 sites, and after 60 days of EAE spontaneous development (Spont-aH3-60d) at 12 sites; only 6 of them are the same (Table 2). Twenty days after immunization of mice with MOG and the DNA-histone complex, the number of sites decreases to 8 and 9, respectively. In the first case (MOG20-aH3) are observed 4, while in the second (DNA20-aH3), 6 sites are coinciding with those for Con-aH3-0d (Table 2). In the case of DNA60-aH3, 13 sites of histone H3 hydrolysis were found, and several of them coincide with sites in: 8 (Spont-aH3-60d), 7 (Con-aH3-0d and Con-aH3-0d), and 4 (MOG20-aH3). Overall, the change in the number (8-13) and type of sites of H3 histone hydrolysis by Con-aH3-0d antibodies against this histone, corresponding to different stages of EAE development, is relatively small. However, some IgGs hydrolyze H3 at very specific sites that are absent in the case of other preparations: Con-aH3-0d (M90-A91), Spont-aH3-60d (P43-G44, R53-Y54, and F84-Q85); MOG20-aH3 (H39-R40, F78-K79, and A98-Y99); DNA20-aH3 (A95-C96); DNA60-aH3 (R42-P43, R52-R53, A75-Q76, and Q76-D77). I74-A75 is the only hydrolysis site found for all five anti-H3 histone IgGs. It should be emphasized that those sites that coincide for two or more IgGs samples differ in cleavage efficiency and may be major, moderate, or minor sites in the case of different preparations (Table 2).

|

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H3 and anti-H1 IgGs |

|||||||||

|

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H3 IgGs |

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H1 IgGs |

||||||||

|

Con-aH3-0d |

Spont-aH3-60d |

MOG20- aH3 |

DNA20- aH3 |

DNA60- aH3 |

Con-aH1-0d |

Sponta-H1-60d |

MOG20- aH1 |

DNA20- aH1 |

DNA60- aH1 |

|

11 sites |

12 sites |

8 sites |

9 sites |

13 sites |

15 sites |

21 sites |

15 sites |

20 sites |

9 sites |

|

Q5-T6** |

Q5-T6 |

- |

- |

- |

Q5-T6 |

- |

- |

Q5-T6** |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

G12-G13 |

- |

- |

|

- |

P43-G44** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

V35-K36 |

V35-K36 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K37-P38 |

- |

- |

|

P38-H39 |

- |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

- |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

|

- |

- |

H39-R40 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

H39-R40 |

H39-R40 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R40-Y41 |

R40-Y41 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

R42-P43 |

R42-P43 |

R42-P43 |

R42-P43 |

R42-P43 |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P43-G44 |

P43-G44 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A47-L48 |

A47-L48 |

- |

- |

- |

|

L48-R49 |

L48-R49 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L48-R49 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E50-I51 |

- |

E50-I51 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

R52-R53 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

R53-Y54 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

Y54-Q55 |

Y54-Q55 |

Y54-Q55 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y54-Q55 |

Y54-Q55 |

|

Q55-K56 |

- |

- |

- |

Q55-K56 |

Q55-K56 |

Q55-K56 |

- |

Q55-K56 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

T58-E59 |

- |

- |

- |

|

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

- |

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

- |

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R63-K64 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K64-L65 |

K64-L65 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L65-P66 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P66-F67 |

P66-F67 |

- |

- |

- |

|

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

- |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R69-L70 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

|

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

A75-Q76 |

A75-Q76 |

A75-Q76 |

A75-Q76 |

A75-Q76 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q76-D77 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

D77-F78 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

F78-K79 |

|

- |

F78-K79 |

F78-K79 |

F78-K79 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R83-F84 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

F84-Q85 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q85-S86 |

- |

Q85-S86 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S86-S87 |

- |

- |

- |

|

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

- |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

- |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

|

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

- |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

- |

- |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

|

M90-A91 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

A95-C96 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

A98-Y99 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A98-Y99 |

- |

|

L103-F104 |

- |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

- |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

- |

|

* The molecular weights of the histone hydrolysis products were used for the estimation of the corresponding sites of hydrolysis based on a set of data from 9–10 spectra. **Major sites of hydrolysis are shown in red, moderate sites in black, and minor sites in blue. Missing splitting sites are marked with a dash (-). |

|||||||||

As was shown earlier using the examples of hydrolysis of H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 histones by antibodies against five H1-H4 histones, the number of splitting sites and their type can vary greatly depending on the histone hydrolyzed, antibody preparation used and the stage of EAE development [43-46]. While the number of H3 hydrolysis sites for different IgGs against this histone did not differ much, it was found that the number and type of splitting sites of H3 histone with IgGs against H1 histone could greatly both increase or decrease compared to time zero (Table 2). The spontaneous achievement of EAE leads to an increase in the number of H3 histone hydrolysis by IgGs against H1 histone from 15 (Con-aH1-0d) to 21 (Spont-aH1-60d); 9 other major and moderate H3 histone hydrolysis sites appear (Table 2). Treatment of mice with MOG does not lead to a change in the number of hydrolysis sites compared to time zero, but only 7 of 15 sites for Con-aH1-0d and MOG20-aH1 are the same (Table 2). Interestingly, not only the spontaneous development of EAE, but also immunization of mice with the DNA-histones complex leads to an increase in the number of H3 hydrolysis sites for DNA20-aH1 from 15 to 20, but only 9 of them are similar to those for Con-aH1-0d. Moreover, out of 21 (Spont-aH1-60d) and 20 (DNA20-aH1) sites, only 7 sites coincide, but they differ in hydrolysis efficiency. Somewhat unexpectedly, specific changes in the differentiation profile of stem cells after immunization of mice with the DNA-histones complex first during 20 days leads to an increase in the sites of hydrolysis of H3 with anti-H1 antibodies to 21, and then by 60 days (DNA60-aH1) to a decrease to 9 sites (Table 2). Eight of the 9 hydrolysis sites of H3 splitting by DNA60-aH1 are among the 21 sites in the case of DNA20-aH1.

The number of sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgGs against H2A histone (Con-aH2A-0d) at zero time is maximal (16) but then decreases to: 11 (Spont-aH2A-60d), 12 (MOG20-aH2A and DNA20-aH2A) and 10 sites (DNA60-aH2A) (Table 3). It is interesting that for all five IgGs against H2A, there is not at least one common hydrolysis site for them. It is interesting that the development of EAE from 20 to 60 days after immunization of mice with the DNA-histones complex occurs in such a way that for the IgGs there are only two common sites for hydrolysis of H3 histone by DNA20-aH2A and DNA60-aH2A (Table 3). A feature of antibodies against H2A is that the sites of hydrolysis of H3 histone by Con-aH2A-0d and Spont-aH2A-60d are very rare in the case of IgGs after immunization of mice with MOG and DNA-histones complex (Table 3).

|

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H2A IgGs |

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H2B IgGs |

||||||||

|

Con-aH2A-0d |

Spont-aH2A-60d |

MOG20—aH2A |

DNA20—aH2A |

DNA60—aH2A |

Con-aH2B-0d |

Spont-aH2B-60d |

MOG20—aH2B |

DNA20—aH2B |

DNA60—aH2B |

|

16 sites |

11 sites |

12 sites |

12 sites |

9 sites |

13 sites |

13 sites |

16 sites |

6 sites |

7 sites |

|

- |

Q5-T6** |

- |

Q5-T6** |

- |

Q5-T6 |

Q5-T6** |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R8-K9 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

G12-G13 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K23-A24 |

K23-A24 |

K23-A24 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K27-S28 |

- |

- |

|

V35-K36 |

V35-K36 |

V35-K36 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

- |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

|

H39R40 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R40-Y41 |

- |

- |

- |

|

R42-P43 |

- |

R42-P43 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P43-G44 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

L48-R49 |

- |

- |

L48-R49 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

R49-L50 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

E50-I51? |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R52 -R53 |

- |

R52-R53 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R53-Y54 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

Y54-Q55 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y54-Q55 |

- |

- |

|

Q55-K56 |

- |

Q55-K56 |

- |

- |

Q55-K56 |

Q55-K56 |

Q55-K56 |

- |

- |

|

K56-S57 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

L61-I62? |

L61-I62? |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L61-I62 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L64-I65 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

K64-L65? |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

P66-F67 |

- |

- |

- |

P66-F67 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

- |

- |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

- |

Q68-R69 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R69-L70 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

E73-I74 |

- |

- |

- |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

- |

- |

|

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

- |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

- |

|

A75-Q76 |

- |

- |

A75-Q76 |

- |

A75-Q76 |

- |

A75-Q76 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

D77-F78 |

- |

D77-F78 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

F78-K79 |

F78-K79 |

F78-K79 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K79-T80 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

T80-D81 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

L82-R83 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

S87-A78 |

S87-A78 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

A78-V79 |

A78-V79 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A78-V79 |

- |

- |

|

V79-M80 |

V79-M80 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

V79-M80 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

L82-R83 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L82-R83 |

|

- |

- |

- |

S86-S87 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

S87-A88 |

- |

S87-A88 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

A95-C96 |

- |

- |

A95-C96 |

A95-C96 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

C96-E97 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E97-A98 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y99-L100 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

G103-L103 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

- |

- |

L103-F104 |

L103-F104 |

- |

L103-F104 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

F104-E105 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E107-G106 |

|

- |

- |

- |

V117-T118 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

* The molecular weights of the histone hydrolysis products were used for the estimation of the corresponding sites of hydrolysis based on a set of data from 9–10 spectra. **Major sites of hydrolysis are shown in red, moderate sites in black, and minor sites in blue. Missing splitting sites are marked with a dash (-). |

|||||||||

The number of sites (13) of hydrolysis of H3 histone by IgGs against H2B at the beginning of the experiment (Con-aH2B-0d) and after 60 days of spontaneous development of EAE for 60 days (Spont-aH2A-60d) coincided, but only 9 of them are common to these preparations (Table 3). Immunization of EAE-prone mice with MOG leads to the production of lymphocytes producing antibodies hydrolyzing H3 at 16 sites (MOG20-aH2B) and with a different specificity. In a set of polyclonal MOG20-aH2B IgGs there are antibodies hydrolyzing H3 in another polypeptide chain, G12-K27, P43-L48, and A78-V79, but there are no hydrolysis sites from S87 to L103 amino acids (AAs) which are characteristic of Con-aH2B-0d and Spont-aH2A-60d. Treatment of mice with the DNA-histone complex leads to another change in the production of antibodies against H2B histone - a decrease in H3 hydrolysis sites to 6 (DNA20-aH2B) and 7 (DNA60-aH2B) compared to zero time; only two hydrolysis sites for two last IgGs are common for these preparations (Table 3).

Data on sites of hydrolysis of H3 by antibodies against histone H4 and MBP are given in Table 4.

|

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-H4 IgGs |

Sites of H3 hydrolysis with anti-MBP IgGs |

||||||||

|

Con-aH4-0d |

Spont-aH4-60d |

MOG20-aH4 |

DNA20-aH4 |

DNA60-aH4 |

Con-aMBP-0d |

Spont-aMBP-60d |

MOG20-aMBP |

DNA20-aMBP |

DNA60-aMBP |

|

18 sites |

6 sites |

20 sites |

8 sites |

5 sites |

14 sites |

21 sites |

12 sites |

9 sites |

8 sites |

|

- |

- |

Q5-T6** |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q5-T6 |

Q5-T6 |

Q5-T6 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

A7-R8 |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R8-K9 |

R8-K9 |

- |

|

- |

G12-G13** |

- |

- |

- |

G12-G13** |

G12-G13 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

K14-A15 |

K14-A15 |

- |

|

- |

- |

K18-Q19 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

L20-A21 |

L20-A21 |

|

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

A25-R26 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

A31-T32 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

V35-K36 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

K37-P38 |

K37-P38 |

K37-P38 |

K37-P38 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

P38-H39 |

P38-H39 |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

H39-R40 |

- |

- |

H39-R40 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R40-Y41 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y41-R42 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

R42-P43 |

- |

- |

R42-P43 |

- |

- |

- |

|

P43-G44 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P43-G44 |

P43-G44 |

- |

P43-G44 |

P43-G44 |

|

- |

- |

V46-A47 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E50-I51 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y54-Q55 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q55-K56 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

A47-L48 |

- |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

K56-S57 |

- |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L48-R49 |

- |

|

K56-S57 |

K56-S57 |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R53-Y54 |

R53-Y54 |

- |

|

K56-S57 |

Y54-Q55 |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Y54-Q55 |

|

K56-S57 |

- |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q55-K56 |

|

K56-S57 |

- |

K56-S57 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

S57-T58 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

T58-E59 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L60-L61 |

L60-L61 |

- |

- |

|

L61-I62 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L61-I62 |

L61-I62 |

- |

- |

L61-I62 |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

P66-F67 |

P66-F67 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

R63-K64 |

- |

R69-L70 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q68-R69 |

Q68-R69 |

- |

- |

Q68-R69 |

|

- |

- |

R69-L70 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R69-L70 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

L70-V71 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

R72-E73 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

R72-E73 |

- |

|

- |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

E73-I74 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

- |

I74-A75 |

- |

I74-A75 |

I74-A75 |

- |

- |

- |

|

A75-Q76 |

- |

- |

A75-Q76 |

- |

- |

A75-Q76 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

Q76-D77 |

- |

- |

Q76-D77 |

- |

- |

- |

|

D77-F78 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

F78-K79 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

F78-K79 |

- |

- |

- |

|

T80-R81 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

R83-F84 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

F84-Q85 |

- |

F84-Q85 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

Q85-S86 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

S87-A88 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

S87-A88 |

- |

S87-A88 |

|

- |

A88-V89 |

A88-V89 |

- |

- |

A88-V89 |

A88-V89 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

V89-M90 |

- |

- |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

V89-M90 |

|

A91-L92 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Q93-E94 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Q93-E94 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

A95-C96 |

- |

- |

- |

A95-C96 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

C96-E97 |

- |

- |

C96-E97 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E97-A98 |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

Y99-L100 |

- |

- |

- |

Y99-L100 |

Y99-L100 |

- |

- |

|

V101-G102 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

L103-F104 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

L103-F104 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

F104-E105 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

E105-D106 |

- |

- |

- |

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

!117-T118 |

- |

- |

- |

|

I124-Q125 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

* The molecular weights of the histone hydrolysis products were used for the estimation of the corresponding sites of hydrolysis based on a set of data from 9–10 spectra. **Major hydrolysis sites are shown in red, moderate sites in black, and minor sites in blue. Missing splitting sites are marked with a dash (-). |

|||||||||

Only in the case of immunization of mice with MOG (MOG20-aH4), there was an increase in the sites of H3 hydrolysis in comparison with Con-aH4-0 against histone H4 from 18 to 20 (Table 4). Specific changes in the differentiation profile of stem cells during the spontaneous development of EAE as well as immunization of mice with the DNA-histones complex led to the formation of B lymphocytes producing IgGs hydrolyzing H3 at a smaller number of sites: 6 (Spont-aH4-60d), 8 (DNA20-aH4), and 5 (DNA60-aH4). Four of the 6 hydrolysis sites of Spont-aH4-60d coincide with 4 of the 18 sites of Con-aH4-0 but differ in the efficiency of hydrolysis at these sites by these IgGs. Of the eight sites found in the case of DNA20-aH4, only two coincide with those of Con-aH4-0 and Spont-aH4-60d. Two identical hydrolysis sites of H3 were also found for DNA20-aH4 and DNA60-aH4 (Table 4). It should be noted that all five sites of histone H3 hydrolysis by anti-H4 antibodies (DNA60-aH4), unlike other IgG preparations, belong to minor ones (Table 4).

Thus, antibodies against all five histones possess polyspecific binding to H3 histone and cross-catalytic activity - the ability to hydrolyze H3 histone. Interestingly, the spontaneous development of EAE leads to various changes in the production of B lymphocytes that produce antibodies capable of hydrolyzing H3 histone. The number of H3 hydrolysis sites in the case of spontaneous development of EAE for IgGs against different histones may remain almost unchanged [anti-H3 (11-12) and anti-H2B (13-13)], increase [anti-H1 (15-21)] or decrease [anti-H2A (16-11) and anti-H4 (18-6)]. In addition, antibodies against various histones after 60 days of spontaneous development of EAE are very different from Abs at the zero time, not only in the number but also in the type of splitting sites. This indicates that changes in the differentiation of bone marrow stem cells during the spontaneous development of EAE occur in such a way that the formation of lymphocytes producing antibodies against each of five different histones is very different and individual in relation to each histone and stage of EAE development.

As previously shown in several studies [43-46], immunization of mice with MOG and DNA-histones complex leads to different changes in the differentiation profile of bone marrow stem cells among themselves and in comparison, with the spontaneous development of EAE. These differences lead to the fact that at twenty days after immunization of mice with MOG and also 20 and 60 days after their treatment with the DNA-histone complex, the number of sites and their type are very different both in the case of these abzymes and in comparison, with antibodies corresponding to time zero and spontaneous development of EAE. In other words, the immunogens used stimulate such a change in the differentiation profile of HSCs when occurs the predominant formation of lymphocytes synthesizing abzymes with higher activity and altered H3 hydrolysis sites.

As noted above, antibodies against four histones (H1, H2A, H2B, and H4) effectively hydrolyze MBP and vice versa [43-46]. A similar result was obtained in the case of Abzs against histone H3 and MBP. Data on the sites of hydrolysis of histone H3 by IgGs against MBP are given in Table 4. With the spontaneous development of EAE, there is an increase in the sites of H3 hydrolysis in the case of Con-aMBP-0d and Spont-aMBP-60d from 14 to 21 (Table 4). Treatment of mice with MOG (MOG20-aMBP) results in a decrease in H3 hydrolysis sites from 14 to 12. None of the H3 hydrolysis sites in the case of MOG20-aMBP coincide with those for Con-aMBP-0d, but two are identical to those of Spont-aMBP-60d. After immunization of mice with the DNA-histones complex, the number of H3 hydrolysis sites decreased to 9 (DNA20-aMBP) and 8 (DNA60-aMBP) (Table 4). Only two H3 hydrolysis sites coincide for Con-aMBP-0d and DNA20-aMBP antibodies. Three common sites have been discovered for DNA20-aMBP and DNA60-aMBP. As seen from Tables 2-4, the number of H3 hydrolysis sites and their type differs noticeably or strongly in the case of all abzymes versus five histones and MBP.

Discussion

The non-specific complex formation of different enzymes with foreign molecules is a widespread phenomenon [53]. The correct selection of specific substrates by canonical enzymes on the stage of complex formation is, more often, at most, 1-2 orders of magnitude [53]. It is following changes in enzymes and substrates structures that lead to the stage of catalysis, providing the rise in the reaction rate by 5-8 orders of magnitude in comparison with unspecific substrates. Therefore, catalytic cross-reactivity in the case of canonical enzymes is a very rare case [53]. Classical enzymes usually catalyze only one chemical reaction. However, the situation with abzymes against five histones and MBP turned out to be much more complicated. In the case of enzymes there is a simple situation: one gene – one protein. The formation of antibodies to each antigen occurs in a completely different way. Theoretically, the immune system of humans can produce up to 106 variants of Abs against one antigen with different properties [54]. During the V (D) J recombination process, a unique DNA region encoding a variable domain is formed. The variable regions of heavy (H) or light (L) chains are encoded by a locus divided into several fragments - subgenes, which are designated V (variable), D (diversity), and J (joining) [55-57]. After activation by antigen, B cells begin to proliferate rapidly. An increased rate of point mutations is observed in parallel with frequent loci divisions encoding the hypervariable domains of the heavy and light chains. This process is called somatic hypermutation. As a result of this process, the daughter cells resulting from the division will produce antibodies with slightly different variable domains. Thus, somatic hypermutation serves as another mechanism for increasing antibody diversity and affects antibodies' affinity to the antigen [55-57]. As a result, the potential number of B-lymphocytes synthesizing antibodies with various properties, including different abzymes against the same antigen, can be very large.

Similar to many known enzymes, Abzs against many various proteins usually cleave only one specific globular antigen-protein and could not split many other control unspecific proteins [30,31,33,34]. It was first shown that anti-MBP abzymes of patients with several AIDs hydrolyze only MBP, while Abs against histones - only histones [30,31,33,34]. Until recently, there was no data on the catalytic cross-activity of any abzymes against different proteins. However, it was recently demonstrated that HIV-infected IgGs against MBP could hydrolyze not only MBP but also five individual H1-H4 and vice versa - abzymes against these histones effectively hydrolyze MBP [30,31,33,34].

The polyreactivity or polyspecificity of complex formation in the case of various antibodies is a widespread phenomenon [58-63]. Relative affinity for unspecific antigens to Abs is usually significantly lower than for specific ones, and such low-affinity Abs can be eluted from affinity sorbents by 0.1-0.15 M NaCl [30-34]. Therefore, weakly nonspecifically associated Abs were eluted from several affinity sorbents using 0.2 M NaCl. IgGs against MBP and five different histones, in addition, were finally passed through alternative affinity sorbents. First, IgG against five histones (H1-H4) and MBP containing no alternative IgGs were obtained. The fraction of IgGs against all five histones was used to isolate Abs-Abzs against each of the five individual histones.

It was previously shown that polyclonal IgG preparations from the blood plasma of EAE-prone mice used in this study do not contain even small admixtures of canonical proteases [43-46]. The comparison of H1, H2A, H2B, and H4 splitting sites with IgGs against MBP and individual histones well supported this conclusion [43-46]. Data from Tables 2-4 also indicate the absence of classical protease impurities in the antibody preparations used. Trypsin splits different proteins after R (arginine) and K (lysine) residues. The H3 histone sequence contains 13 sites for potential cleavage of H3 by trypsin after K and 18 sites after R. Chymotrypsin splits different proteins after F (phenylalanine), Y (tyrosine), and W (tryptophan) aromatic AAs. However, the number of sites of H3 hydrolysis by all IgG-abzymes after K, R, F, and Y residues is small (Tables 2-4).

In contrast to classical proteases, the sites of H3 hydrolysis by all IgGs-abzymes are mainly grouped in specific clusters of H3 histone sequence and mainly occur after neutral AAs: A, L, Q, T, G, and V (Tables 2-4). The specific sites of H3 hydrolysis by all preparations of IgG-abzymes against five histones and MBP do not correspond to those for chymotrypsin and trypsin. They are not disposed along the entire length of H3 histone but are grouped into particular AA clusters.

The strong evidence that the IgGs-abzymes against five individual histones and MBP do not contain even at least noticeable impurities of Abzs against alternative histones follows from a very different number of specific sites of H3 hydrolysis by IgGs against each individual histone and MBP (Tables 2-4). Impotently, the number of H3 splitting sites by preparations of different IgG-abzymes varies from 5 to 21 (Tables 2-4). A specific set of splitting sites was found for each IgG-abzyme preparation, and a very weak coincidence of cleavage sites in the case of various IgG preparations was revealed (Tables 2-4). All groups of cleavage sites differ not only in their location in H3 protein sequence but also the same hydrolysis sites in the case of different IgGs-abzymes vary greatly in the relative efficiency of H3 hydrolysis; major, medium, and minor sites (Tables 2-4).

As shown in Tables 2-4, 29 IgG preparations exhibit different major sites in H3 histone hydrolysis. Therefore, it is interesting to understand why at different stages of spontaneous development of EAE and after mice treatment with MOG and DNA-histones complex, the formation of abzymes hydrolyzing H3 histone at different sites is possible. For this, it is helpful to analyze some literature data.

First, unexpectedly high occurrence of catalytic antibodies in AID mice was observed in comparison with normal conventionally used mouse strains [63,64]. This is due to the fact that only in the case of mice predisposed to AIDs does a change in the differentiation of stem cells occur, which leads to the production of abzyme-producing lymphocytes [30-34]. In addition, multiple sclerosis is at least a two-phase pathology [65-67]. The cascade of specific reactions at the first inflammatory phase is very complex, involving several chemokines, cytokines, various proteins, enzymes, macrophages, and other cells producing osteopathin, and NO radicals [65]. The coordinated action of B- and T-cell, mediators of inflammation, complement system, and auto-Abs results in the formation of demyelination and disturbance of axons. The neurodegenerative stage of disease that appears later is associated directly with neural tissue destruction [65]. Therefore, during the analysis of medicine, immunological, and biochemical indices of MS, every specific phase of MS must be considered, including changes in systemic metabolic specificities, immunoregulation, and exhaustion of different adaptive and compensatory mechanisms [65-67]. During the spontaneous and antigen-induced EAE development at different stages, there may be an association of every individual histones and their complexes, as well as MBP with other different proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, polysaccharides, cells, etc.