Abstract

The hyperpolarization of neuronal membranes through the activation of potassium and chloride channels is a significant mechanism involved in the antinociceptive effects of various drugs. Thus, in this study, we aimed to determine whether potassium or chloride channels mediate the peripheral antinociceptive effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs). The mechanical paw pressure test was utilized as an algesimetric method. Hyperalgesia was induced by intraplantar injection of prostaglandin E2. The EETs (5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET) and the channel blockers were administered intraplantar in male Swiss mice (n=4). Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post-test. Glibenclamide (Glib; 80 μg/paw), a blocker of ATP-sensitive K+ channels; tetraethylammonium (TEA; 30 μg/paw), a blocker of voltage-gated K+ channels; dequalinium (DQ; 50 μg/paw), a blocker of small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels; and paxilline (Pax; 20 μg/paw), a blocker of high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, did not alter the peripheral antinociception induced by 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET. All blockers, when administered alone, did not change the nociceptive threshold of the animals. Niflumic acid (Nifl. Ac.; 32 μg/paw), a selective calcium-activated chloride channels blocker, did not reverse the peripheral antinociceptive effect of 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET. In conclusion, these results suggest that the peripheral antinociceptive effects of 5,6-, 8,9-,11,12-, and 14,15-EET do not appear to be related to the opening of potassium or chloride channels.

Keywords

Antinociception, EET, Chloride channels, Potassium channels

Introduction

Hyperpolarization occurs when the membrane potential becomes more negative at a specific location. This event takes place when ion channels regulate the movement of certain ions into or out of the cell, altering the electrical field of the biological membrane across various systems. For instance, the efflux of K+ through K+ channels and the influx of Cl- through the Ca2+-activated chloride channels (CaCCs) can lead to hyperpolarization [1].

K+ channels are the most common and diverse class of ion channels in neurons [2]. When activated, K+ channels facilitate an extremely rapid efflux of K+ across the membrane, influencing the threshold, waveform, and frequency of the electrical signal in the neuronal membrane, leading to repolarization and even hyperpolarization. Moreover, applying K+ channel activators peripherally can reduce the excitability of free nerve endings (FNE) and dorsal root ganglion (DRG), while K+ channel blockers can enhance firing [2-5]. The literature describes the involvement of K+ channels in the peripheral antinociception of hydrogen peroxide [6] and cannabidiol [7].

CaCCs are present in various areas associated with pain management, including the DRG, the spinal cord, and neurons in the autonomic system. This family of channels also contributes to regulating membrane excitability, generating after-polarizations, and affecting membrane oscillatory behavior [8]. Our group demonstrated the involvement of CaCCs in the CB1 cannabinoid receptors-induced peripheral analgesia [9].

A majoritarian of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) signaling is linked to its K+ channel activation capacity. In smooth vascular muscle, this mechanism causes hyperpolarization and relaxation [10]. Furthermore, although there is no data regarding the possible activation of CaCCs induced by EETs, it has been noted that EETs inhibit volume-activated chloride channels (VACCs) in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells through a cGMP-dependent pathway [11].

The literature indicates that molecules inducing hyperpolarization of the neuronal membrane can reduce excitatory transmission, primarily mediated by nociceptive afferent fibers, thereby enhancing neural inhibitory transmission by decreasing nociceptive signaling [12].

In this study, we aimed to describe the final activator of the antinociceptive pathway of EETs and to determine whether their effects depend on the activation of K+ and CaCCs.

Methods

Animals

Male Swiss mice weighing between 30 and 40 g were housed at the Bioterism Center of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (CEBIO-ICB/UFMG) with free access to food and water. They were maintained under a light/dark cycle of 12 hours (6:00-18:00 h) and at a controlled temperature of 24 ± 2°C. After the tests, the animals were euthanized with a high-dose intraperitoneal injection of an anesthetic mixture (300 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride and 15 mg/kg xylazine hydrochloride, both Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The Ethics Committee on Animal Experimentation (CEUA-UFMG) approved the project, which included calculations for sample size, the algesimetric method, euthanasia, and all procedures involving experimental animals under protocol 75/2017. Our study strictly followed the ARRIVE(Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Drugs

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was diluted in 2% ethanol in a sterile aqueous solution of sodium chloride (NaCl) 0.9% (sterile saline solution). 5,6-epoxieicosatrienoic acid (5,6-EET) (Cayman Chemical, EUA) was dissolved in methyl acetate in saline solution. 8,9-epoxieicosatrienoic acid (8,9-EET) (Cayman Chemical, EUA) and 11,12-epoxieicosatrienoic acid (11,12-EET) (Cayman Chemical, EUA) were dissolved in 6.4% ethanol in saline solution. 14,15-epoxieicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EET) (Cayman Chemical, EUA) was dissolved in 25.6% ethanol in saline solution. Glibenclamide (Tocris Bioscience), an ATP-dependent K+ channel (KATP) blocker, was dissolved in 1% Tween20 in saline solution; tetraethylammonium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich), a voltage-dependent K+ channel blocker, dequalinium dichloride (Tocris Bioscience), a selective blocker of the small conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel, and paxilline (Tocris Bioscience), a potent blocker of high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels, were dissolved in isotonic saline. All the drugs were injected via intra-plantar (i.pl.) in a volume of 20 μl.

Measurement of nociceptive threshold

Hyperalgesia was induced using prostaglandin E2 (PGE2; 2 µg) via an intraplantar injection in the right hind paw. The mechanical nociceptive threshold was expressed in grams (g) and assessed by measuring the response to a paw pressure test (Ugo-Basile; SRL, Varese, Italy), as previously described in rats [13] and mice [14]. The test utilizes a cone-shaped paw presser with a rounded tip that applies a linearly increasing force to the hind paw. The weight in grams needed to elicit the nociceptive response of paw withdrawal was identified as the nociceptive threshold. A cutoff value of 150 g was set to minimize the risk of paw damage.

The nociceptive threshold of the right paw was measured as the average of three consecutive trials recorded before and 180 minutes after the PGE2 injection. Hyperalgesia was calculated as the difference between these two averages (Δ of nociceptive threshold).

Experimental protocol

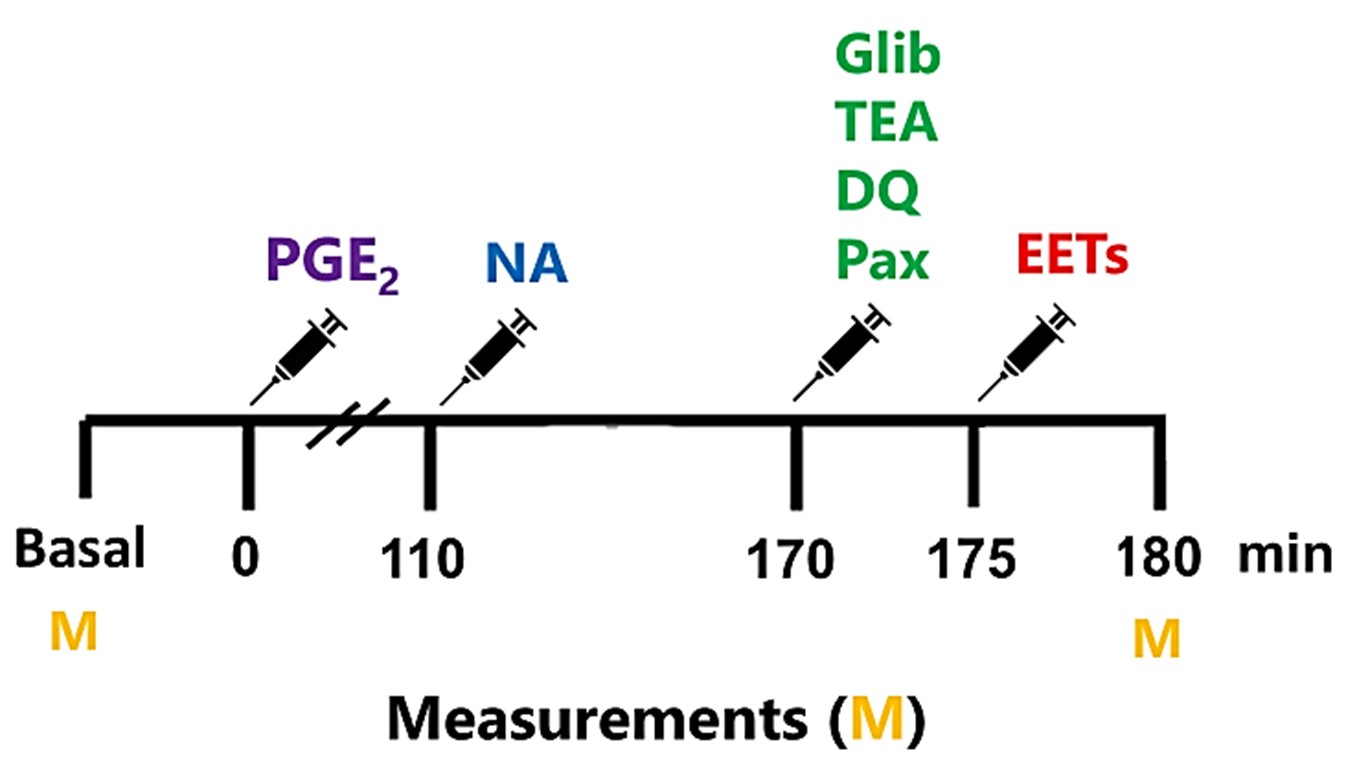

The basal threshold was measured before the experiments, indicating no drug effects (Figure 1). Subsequently, PGE2 was administered at the onset (zero minutes). To assess whether K+ and CaCC blockers can reverse the antinociceptive effect of EETs, either EETs or their vehicle were injected at 175 minutes. Selective blockers of voltage-gated potassium channels, ATP-sensitive potassium channels, and large and small conductance calcium-activated potassium channels were administered at 170 minutes. The Ca2+-activated Cl- channel blocker or vehicle was injected at 110 minutes. The timing of drug injections is based on the peak action of each antagonist or inhibitor, aligning with the peak effect of all during the evaluation of the nociceptive threshold (180 minutes after PGE2 injection in the hind paw).

Figure 1. Experimental protocol for evaluating the involvement of ion channels in the antinociceptive effect of EETs. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and EETs were administered into the right hind paw at 0 and 175 minutes, respectively. All potassium channel blockers, including glibenclamide (Gli), Tetraethylammonium (TEA), dequalinium (DQ), and paxilline (Pax), were administered at 170 minutes, while the chloride channel blocker niflumic acid was given at 110 minutes. All measurements (M) were taken before drug administration (Basal) and at 180 minutes.

Data and statistical analysis

All results are presented in the graphics as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 software, and the data underwent a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by a Bonferroni post-test for multiple comparisons. Only p-values less than 0.01 (p<0.01) were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study on the participation of K+ channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effect of EETs

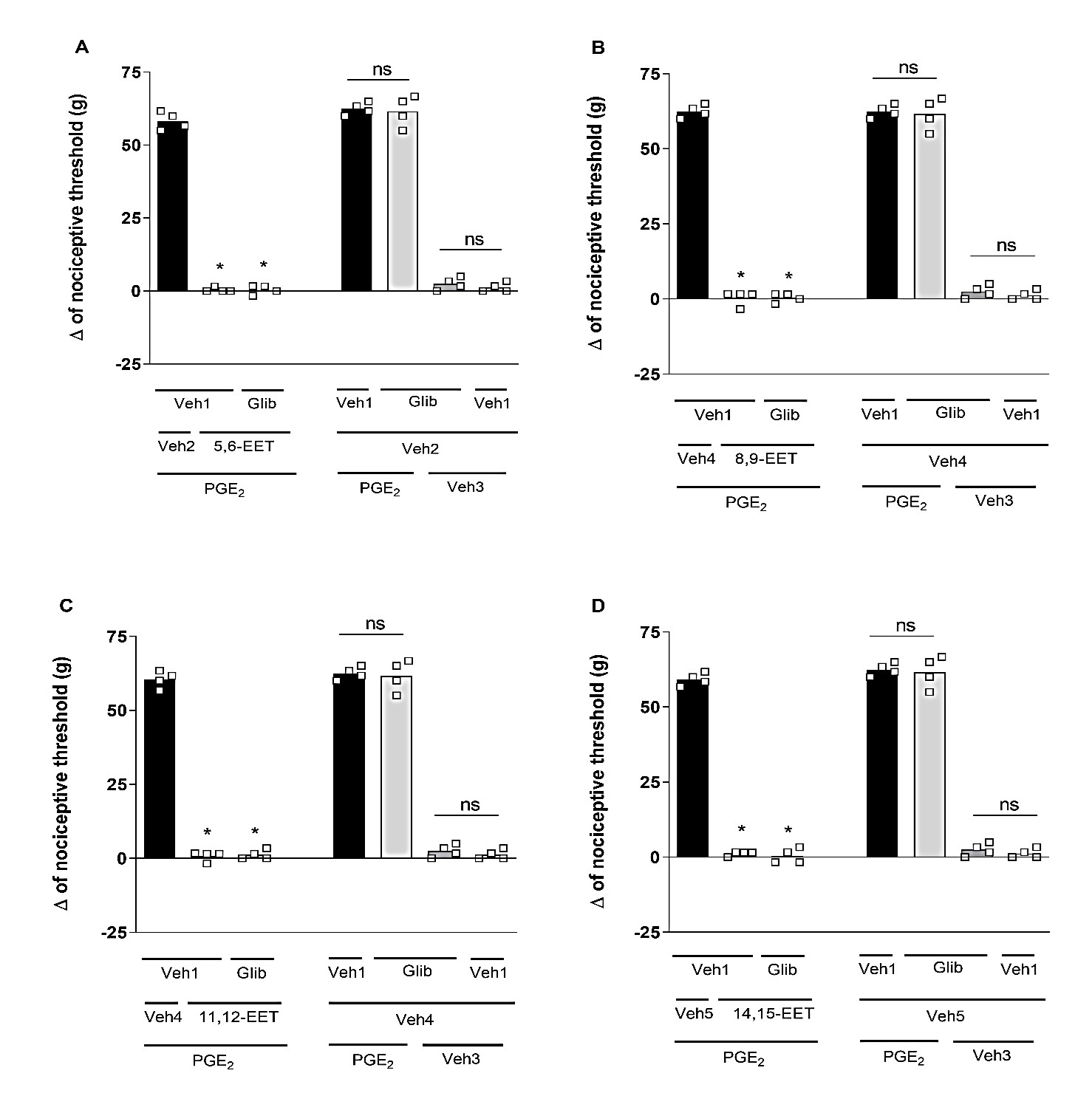

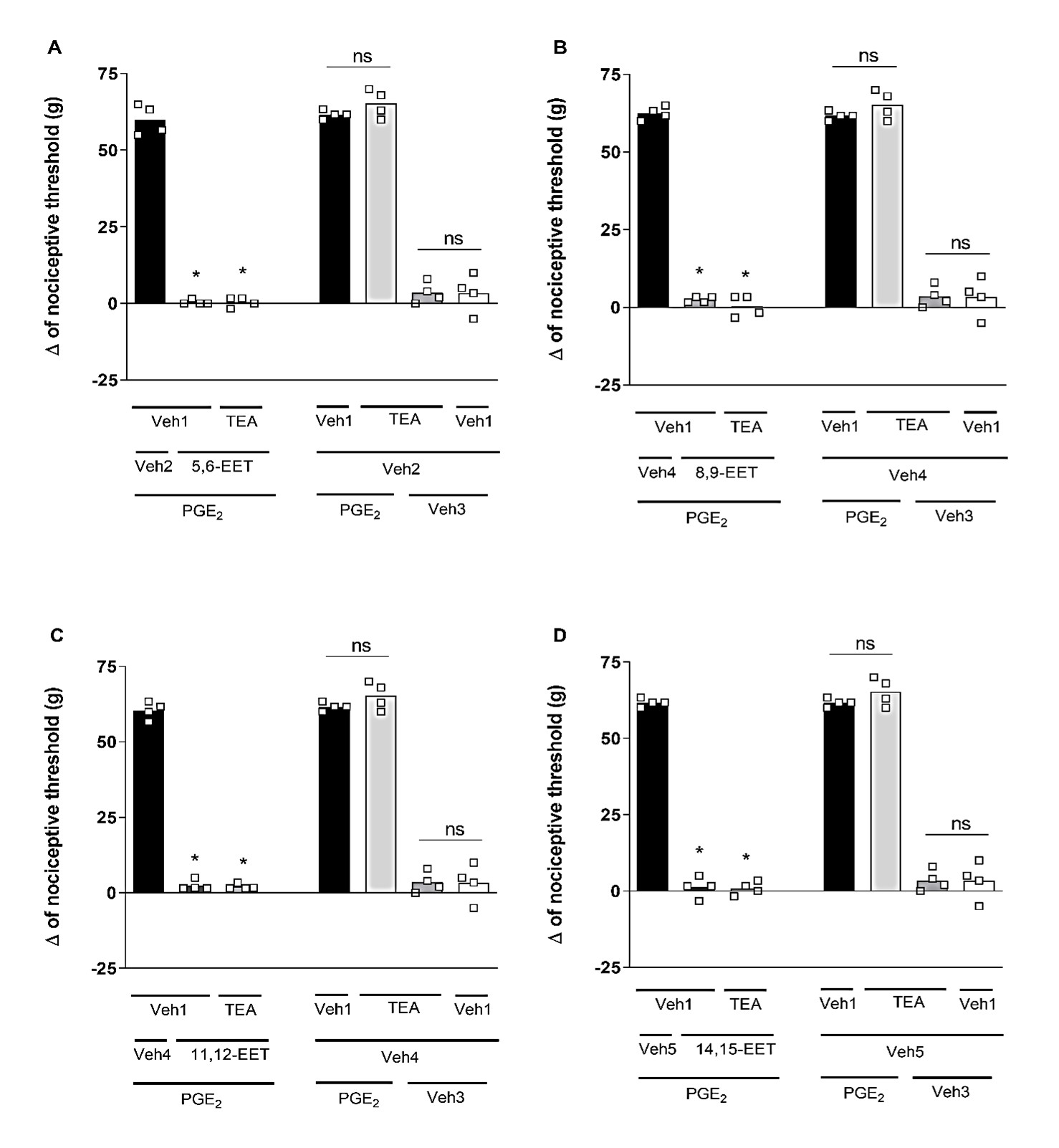

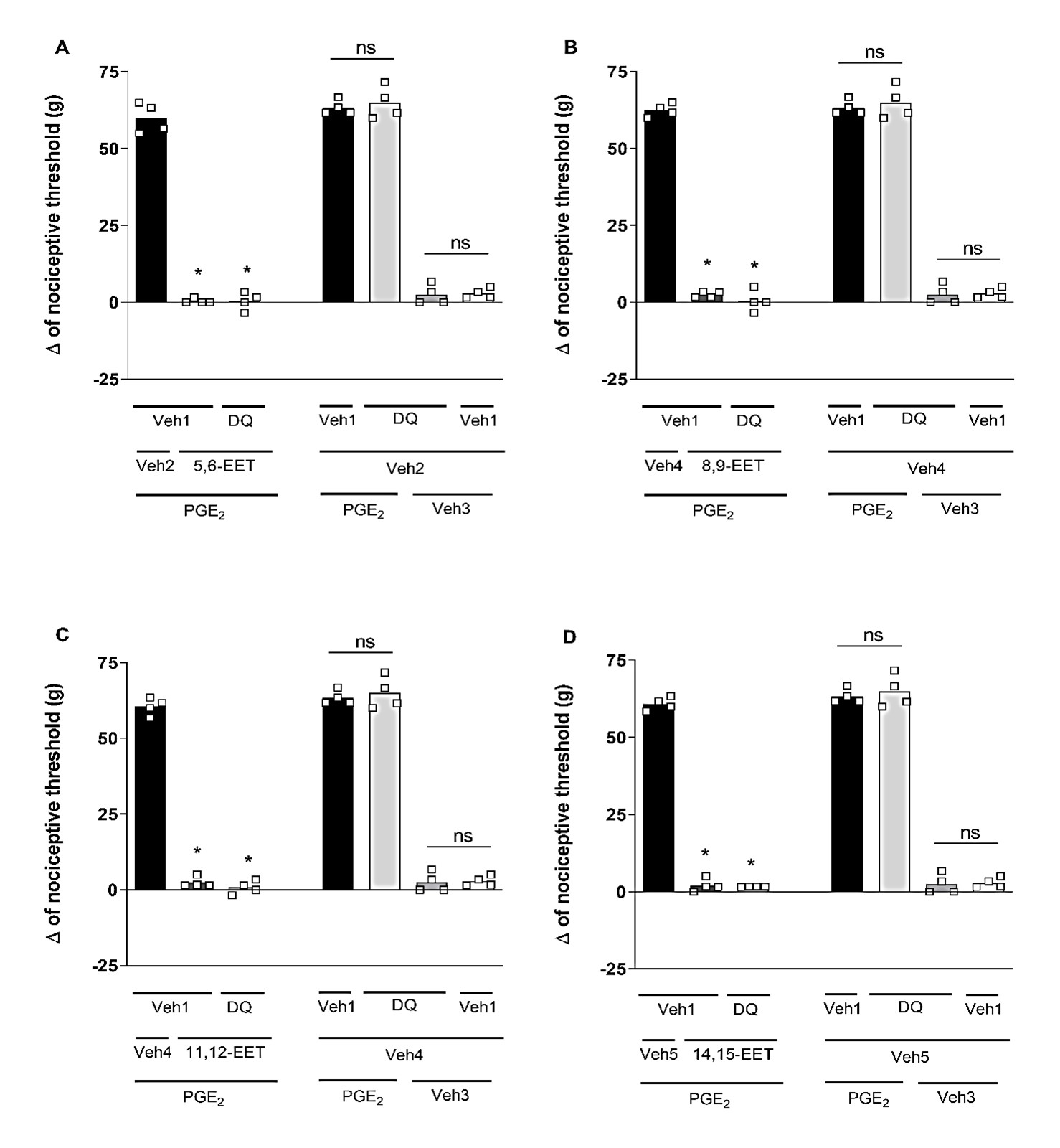

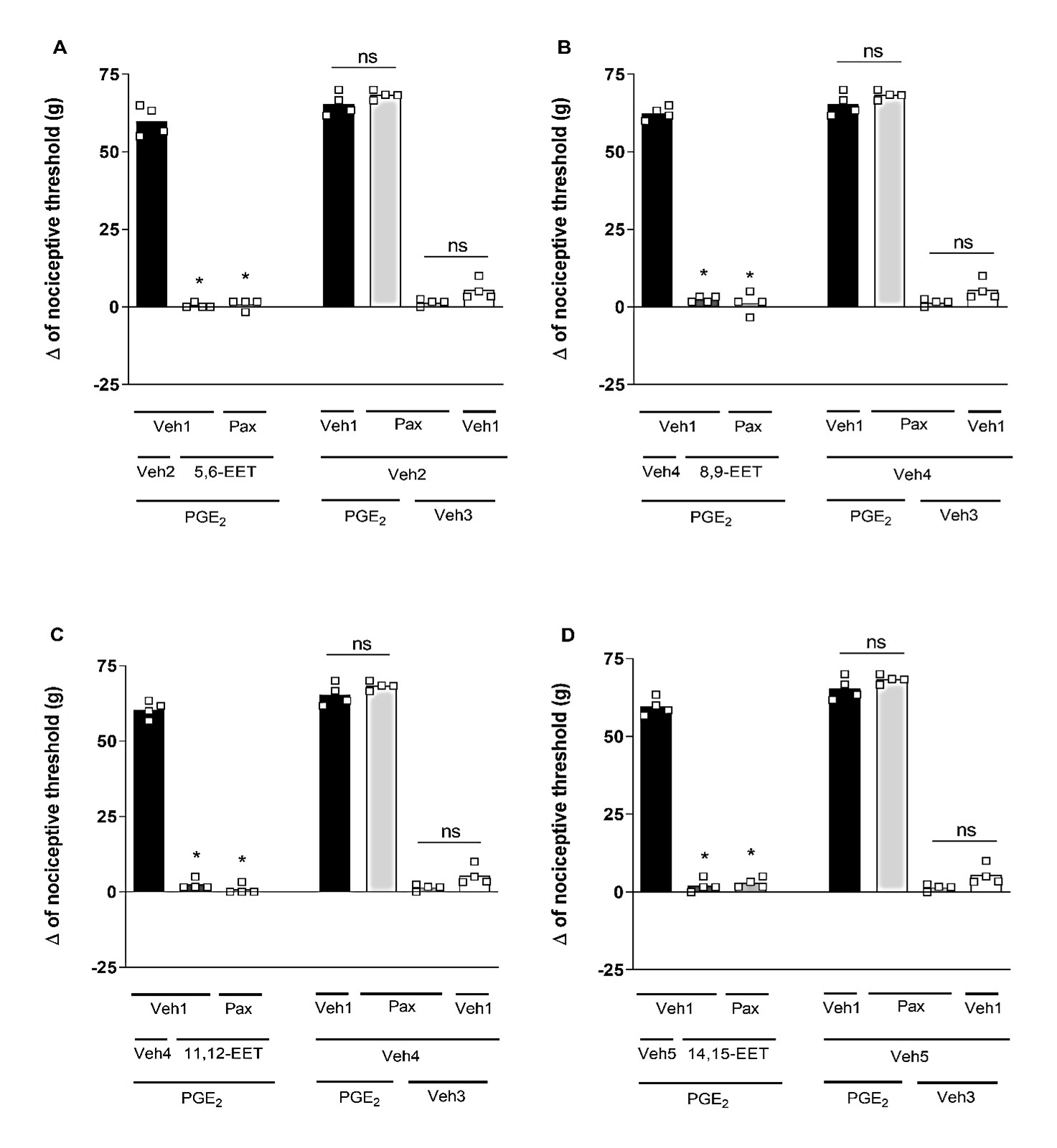

Selective blockers for different K+ channels were utilized: (I) glibenclamide (Glib; 80 μg/paw), a blocker of ATP-sensitive K+ channels; (II) tetraethylammonium (TEA; 30 μg/paw), a blocker of voltage-gated K+ channels; (III) dequalinium (DQ; 50 μg/paw), a blocker of small conductance calcium-activated K+ channels; and (IV) paxilline (Pax; 20 μg/paw), a blocker of high-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Glib (Figure 2), TEA (Figure 3), DQ (Figure 4), and Pax (Figure 5) did not affect the peripheral antinociception induced by 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12- and 14,15-EET. When administered individually, none of the blockers altered the nociceptive threshold of the animals.

Figure 2. Effect of glibenclamide on the peripheral antinociception of EETs. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of the Δ of nociceptive threshold in grams (g). n=4 mice/group. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) compared to PGE2 + Veh + Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). V1 (vehicle 1) = 1% tween 20; V2 (vehicle 2) = 6.4% methyl acetate; V3 (vehicle 3) = 6.4% ethanol; V4 (vehicle 4) = 25.6% ethanol.

Figure 3. Effect of tetraethylammonium on the peripheral antinociception of EETs. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of the Δ of nociceptive threshold measured in grams (g). n=4 mice/group. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) when compared with PGE2 + Veh + Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni post test). V1 (vehicle 1) = saline; V2 (vehicle 2) = methyl acetate 6.4%; V3 (vehicle 3) = ethanol 6.4%; V4 (vehicle 4) = ethanol 25.6%.

Figure 4. Effect of dequalinium on the peripheral antinociception of EETs. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of Δ nociceptive thresholds in grams (g). n=4 mice/group. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) compared to PGE2 + Veh + Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). V1 (vehicle 1) = saline; V2 (vehicle 2) = methyl acetate 6.4%; V3 (vehicle 3) = ethanol 6.4%; V4 (vehicle 4) = ethanol 25.6%.

Figure 5. Effect of paxilline on the peripheral antinociception of EETs. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of the Δ of nociceptive threshold measured in grams (g). n=4 mice per group. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) when compared to PGE2 + Veh + Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). V1 (vehicle 1) = saline; V2 (vehicle 2) = methyl acetate 6.4%; V3 (vehicle 3) = ethanol 6.4%; V4 (vehicle 4) = ethanol 25.6%.

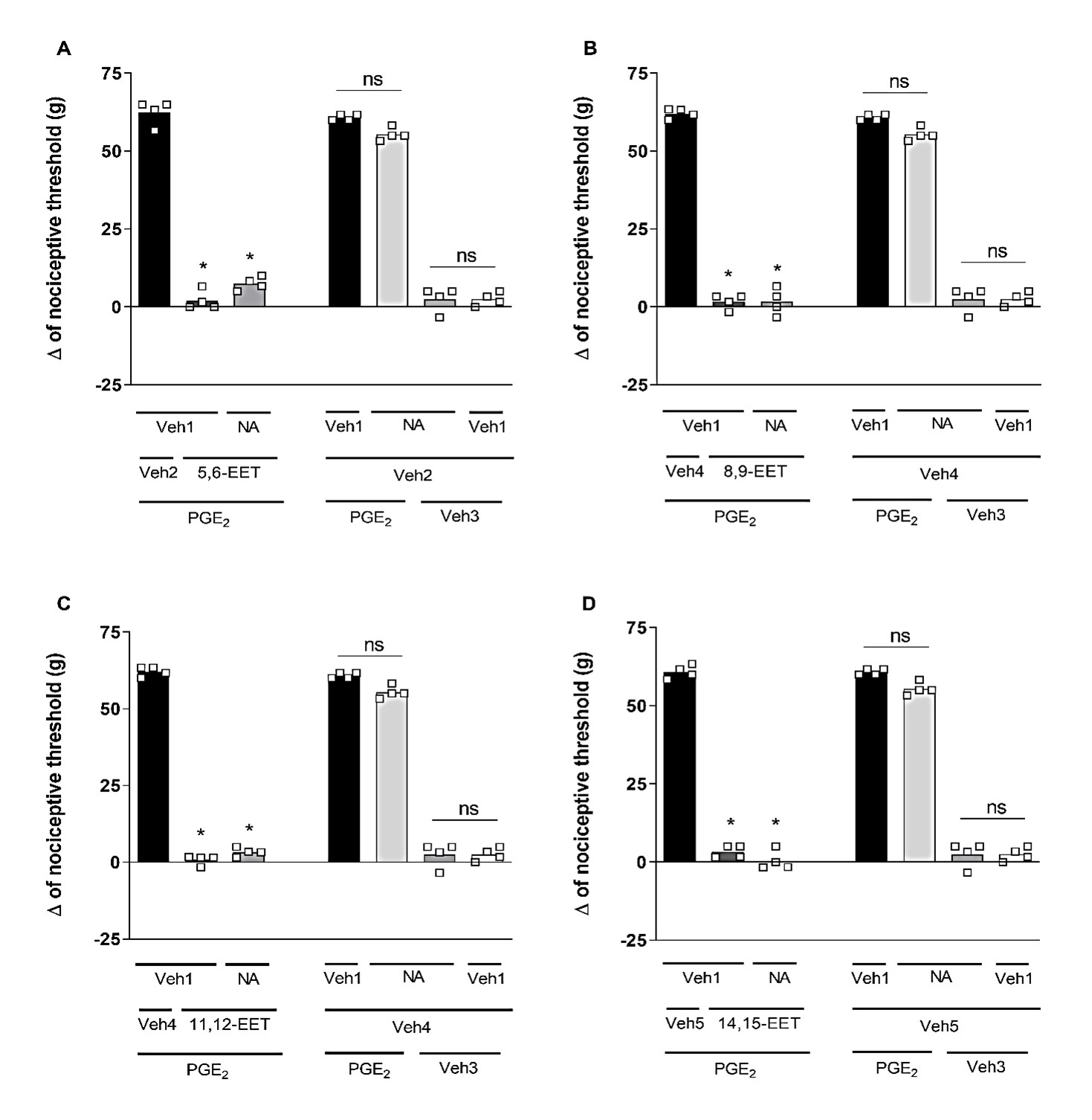

Study on the participation of Ca2+-activated Cl- channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effect of EETs

Niflumic acid (Nifl. Ac.; 32 μg/paw), a selective blocker of CaCCs, could not reverse the peripheral antinociceptive effect of 5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12-, and 14,15-EET (Figure 6). Furthermore, when administered alone, Niflumic acid did not affect the response to PGE2 or the vehicle.

Figure 6. Effect of niflumic acid on the peripheral antinociception of EETs. Each column represents the mean ± SEM of the Δ of nociceptive threshold measured in grams (g). n=4 mice per group. * indicates a significant difference (P<0.01) compared to PGE2 + Veh + Veh (ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test). V1 (vehicle 1) = 3.2% acetone; V2 (vehicle 2) = 6.4% methyl acetate; V3 (vehicle 3) = 6.4% ethanol; V4 (vehicle 4) = 25.6% ethanol.

Discussion

In previous work, our group described the antinociceptive effects of the four regioisomeric forms of EETs against a PGE2 acute pain model, utilizing the paw pressure test to assess the mechanical nociceptive threshold, as previously mentioned [14]. The maximal analgesic effects were observed at a dose of 128 ng for the 5-6, 8-9, and 11-12 EETs, and at 512 ng for the 14-15 EET. Sub-maximal antinociceptive effect doses were identified at 32 ng for the 5-6, 8-9, and 11-12 EETs, and at 256 ng for the 14-15 EET [15]. Therefore, both of these doses were used in the tests of the present work to examine the role of potassium (K+) and CaCCs in the antinociceptive mechanism of EETs.

Therefore, to determine whether the antinociceptive effect of EETs arises from the opening of these channels, we utilized selective blockers from various potassium channels: ATP-sensitive (Glib), voltage-dependent (TEA), and those activated by small (DQ) and large (Pax) conductance calcium-activated K+ channels. However, none of these blockers were able to alter the EETs-induced antinociception, indicating that K+ channels are not involved in this process. It is important to note that the doses used in these experiments have previously been tested with positive results by our research group, demonstrating that EETs can produce antinociception and that this Glib dose could reverse the peripheral antinociceptive effect of ketamine [16], palmitoylethanolamine [17], and dipyrone [18]. Similarly, the same dose of TEA reversed the peripheral antinociception induced by Baclofen [19], while the doses of DQ and Pax reversed the peripheral antinociceptive effects of dopamine and hydrogen peroxide [6,20].

Literature indicates that EETs can be considered as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHF) because they induce hyperpolarization and subsequent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle cells by opening high-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels [21-24]. It has been shown that 11,12-EET stimulates the activation of the KCa channel in small bovine coronary arteries, suggesting that the increased activity of the KCa channel results from the activation of a guanosine triphosphate (GTP) binding protein, likely following the activation of a GS protein-coupled receptor [25]. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the effect of EETs enhances the open probability of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in organ-cultured human bronchi, generally resulting in membrane hyperpolarization [26].

Although EETs have demonstrated this function in the vasculature mediated by potassium channels, none of the potassium channels assessed in our model seem to be involved in the antinociceptive effect exhibited by these substances. Following the experiments conducted by our group, K+ channels were not implicated in the peripheral antinociception of bremazocin, a κ-opioid agonist [27]. However, this drug activates opioid receptors and the NO/cGMP pathway, typically resulting in the activation of K+ channels [28,29]. Furthermore, the literature highlights the role of other channels associated with antinociception mechanisms.

Previous studies have shown that activating opioid [30,31] and cannabinoid receptors [9] induces antinociception that relies on CaCCs. A distinct expression pattern has also been observed in CaCCs within the nociceptive pathway [32]. Therefore, we use a CaCC blocker, niflumic acid, to assess its role in the peripheral antinociception of EETs. However, blocking these channels does not affect the peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by EETs, suggesting that CaCCs are not involved in this mechanism.

In addition to the hyperpolarization-induced antinociceptive mechanisms mediated by K+ and CaCCs, several studies have demonstrated that calcium channels also play a critical role in modulating nociceptive transmission [33,34]. Research shows that blocking N- and P-type voltage-sensitive calcium channels, but not L-type, inhibits formalin-induced nociception in rats [35]. Similarly, it has been suggested that the antinociceptive effects of resveratrol are due to the blockage of calcium channels [36]. The κ-opioid agonist U69,593 induces antinociception that depends on the inhibition of L-type calcium channels [37]. Furthermore, it has been shown that EETs can also regulate L-type calcium channels in the heart [38,39]. While Ca2+-activated K+ channels play a central role in mediating many of EETs' effects in vascular tissue, other molecular targets for EETs may also exist. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels serve as key transducers of external noxious and thermal stimuli at the peripheral terminals of sensory neurons [40].

EETs, including 5,6-EET and 8,9-EET, act as direct TRPV4 agonists [41]. TRPV4 is a Ca2+-permeable cation channel that is widely expressed in the vanilloid subfamily of transient receptor potential (TRP) channels [42]. It activates in response to various stimuli, including warm temperatures. Additionally, TRPV4 transduces hypo-osmotic stimuli in primary afferent nociceptors [43]. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels, leading to smooth muscle hyperpolarization and arterial dilation through Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in response to an endothelial-derived factor [44]. 5,6-EET potently induces a calcium flux (100 nm) in cultured DRG neurons, which is completely abolished when TRPA1 is deleted or inhibited [45].

Conclusion

This manuscript investigates the role of potassium and chloride ion channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effects of EETs using a mouse model. The research employed pharmacological blockers of these channels and a reliable mechanical nociceptive assessment (paw pressure test) to determine whether the analgesic properties of EETs are mediated by ATP-sensitive K+ channels, voltage-gated K+ channels, calcium-activated K+ channels (both small and large conductance), or CaCCs. The results suggest that the peripheral antinociceptive effects of EETs do not appear to be related to the opening of potassium or chloride channels, as the blockers could not alter the effect. This approach, which relies solely on pharmacological methodology, has limitations that subsequent complementary experiments can address. Further research could explore the relationship between EETs-induced antinociception, calcium channels, and TRP.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest concerning the publication of this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and undação de Amparo à Pesquisa de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG).

References

2. Ocaña M, Cendán CM, Cobos EJ, Entrena JM, Baeyens JM. Potassium channels and pain: present realities and future opportunities. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004 Oct 1;500(1-3):203-19.

3. Kajander KC, Bennett GJ. Onset of a painful peripheral neuropathy in rat: a partial and differential deafferentation and spontaneous discharge in A beta and A delta primary afferent neurons. J Neurophysiol. 1992 Sep;68(3):734-44.

4. Passmore GM, Selyanko AA, Mistry M, Al-Qatari M, Marsh SJ, Matthews EA, et al. KCNQ/M currents in sensory neurons: significance for pain therapy. J Neurosci. 2003 Aug 6;23(18):7227-36.

5. Kirchhoff C, Leah JD, Jung S, Reeh PW. Excitation of cutaneous sensory nerve endings in the rat by 4-aminopyridine and tetraethylammonium. J Neurophysiol. 1992 Jan;67(1):125-31.

6. Barra W, Queiroz B, Perez A, Romero T, Ferreira R, Duarte I. Study on peripheral antinociception induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2): characterization and mechanisms. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2024 Oct;397(10):7927-38.

7. Aguiar DD, Petrocchi JA, da Silva GC, Lemos VS, Castor MGME, Perez AC, et al. Participation of the cannabinoid system and the NO/cGMP/KATP pathway in serotonin-induced peripheral antinociception. Neurosci Lett. 2024 Jan 1;818:137536.

8. Hartzell C, Putzier I, Arreola J. Calcium-activated chloride channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:719-58.

9. Romero TR, Pacheco Dda F, Duarte ID. Probable involvement of Ca(2+)-activated Cl(-) channels (CaCCs) in the activation of CB1 cannabinoid receptors. Life Sci. 2013 May 2;92(14-16):815-20.

10. Félétou M, Vanhoutte PM. EDHF: an update. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009 Jul 16;117(4):139-55.

11. Yang C, Kwan YW, Seto SW, Leung GP. Inhibitory effects of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on volume-activated chloride channels in rat mesenteric arterial smooth muscle. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2008 Dec;87(1-4):62-7.

12. Kato G, Furue H, Katafuchi T, Yasaka T, Iwamoto Y, Yoshimura M. Electrophysiological mapping of the nociceptive inputs to the substantia gelatinosa in rat horizontal spinal cord slices. J Physiol. 2004 Oct 1;560(Pt 1):303-15.

13. Randall LO, Selitto JJ. A method for measurement of analgesic activity on inflamed tissue. Arch Int Pharmacodyn Ther. 1957 Sep 1;111(4):409-19.

14. Kawabata A, Nishimura Y, Takagi H. L-leucyl-L-arginine, naltrindole and D-arginine block antinociception elicited by L-arginine in mice with carrageenin-induced hyperalgesia. Br J Pharmacol. 1992 Dec;107(4):1096-101.

15. Fonseca FC, Duarte ID. 5, 6-, 8, 9-, 11, 12-and 14, 15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acids (EETs) Induce Peripheral Receptor-Dependent Antinociception in PGE2-Induced Hyperalgesia in Mice. Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacy Research. 2024 Dec 16;9(2):156-69.

16. Romero TR, Duarte ID. Involvement of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by ketamine. Vet Anaesth Analg. 2013 Jul;40(4):419-24.

17. Romero TR, Duarte ID. N-palmitoyl-ethanolamine (PEA) induces peripheral antinociceptive effect by ATP-sensitive K+-channel activation. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;118(2):156-60.

18. Alves D, Duarte I. Involvement of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in the peripheral antinociceptive effect induced by dipyrone. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002 May 24;444(1-2):47-52.

19. Reis GM, Duarte ID. Baclofen, an agonist at peripheral GABAB receptors, induces antinociception via activation of TEA-sensitive potassium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2006 Nov;149(6):733-9.

20. Gonçalves de Queiroz BF, Cristina de Sousa Fonseca F, Pinto Barra WC, Viana GB, Irie AL, de Castro Perez A, Lima Romero TR, et al. Interaction between the dopaminergic and endocannabinoid systems promotes peripheral antinociception. Eur J Pharmacol. 2025 Jan 15;987:177195.

21. Baron A, Frieden M, Bény JL. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids activate a high-conductance, Ca(2+)-dependent K + channel on pig coronary artery endothelial cells. J Physiol. 1997 Nov 1;504 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3):537-43.

22. Campbell WB, Gebremedhin D, Pratt PF, Harder DR. Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res. 1996 Mar;78(3):415-23.

23. Fisslthaler B, Popp R, Kiss L, Potente M, Harder DR, Fleming I, et al. Cytochrome P450 2C is an EDHF synthase in coronary arteries. Nature. 1999 Sep 30;401(6752):493-7.

24. Quilley J, McGiff JC. Is EDHF an epoxyeicosatrienoic acid? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000 Apr;21(4):121-4.

25. Li PL, Campbell WB. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids activate K+ channels in coronary smooth muscle through a guanine nucleotide binding protein. Circ Res. 1997 Jun;80(6):877-84.

26. Morin C, Sirois M, Echave V, Gomes MM, Rousseau E. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid relaxing effects involve Ca2+-activated K+ channel activation and CPI-17 dephosphorylation in human bronchi. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007 May;36(5):633-41.

27. Amarante LH, Alves DP, Duarte ID. Study of the involvement of K+ channels in the peripheral antinociception of the kappa-opioid receptor agonist bremazocine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004 Jun 28;494(2-3):155-60.

28. Soares AC, Duarte ID. Dibutyryl-cyclic GMP induces peripheral antinociception via activation of ATP-sensitive K(+) channels in the rat PGE2-induced hyperalgesic paw. Br J Pharmacol. 2001 Sep;134(1):127-31.

29. Sachs D, Cunha FQ, Ferreira SH. Peripheral analgesic blockade of hypernociception: activation of arginine/NO/cGMP/protein kinase G/ATP-sensitive K+ channel pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Mar 9;101(10):3680-5.

30. Pacheco Dda F, Pacheco CM, Duarte ID. Peripheral antinociception induced by δ-opioid receptors activation, but not μ- or κ-, is mediated by Ca²⁺-activated Cl⁻ channels. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012 Jan 15;674(2-3):255-9.

31. Pacheco Dda F, Pacheco CM, Duarte ID. δ-Opioid receptor agonist SNC80 induces central antinociception mediated by Ca2+ -activated Cl- channels. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012 Aug;64(8):1084-9.

32. Oh U, Jung J. Cellular functions of TMEM16/anoctamin. Pflugers Arch. 2016 Mar;468(3):443-53.

33. Damaj MI, Welch SP, Martin BR. Involvement of calcium and L-type channels in nicotine-induced antinociception. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993 Sep;266(3):1330-8.

34. Vanegas H, Schaible H. Effects of antagonists to high-threshold calcium channels upon spinal mechanisms of pain, hyperalgesia and allodynia. Pain. 2000 Mar;85(1-2):9-18.

35. Malmberg AB, Yaksh TL. Voltage-sensitive calcium channels in spinal nociceptive processing: blockade of N- and P-type channels inhibits formalin-induced nociception. J Neurosci. 1994 Aug;14(8):4882-90.

36. Pan X, Chen J, Wang W, Chen L, Wang L, Ma Q, et al. Resveratrol-induced antinociception is involved in calcium channels and calcium/caffeine-sensitive pools. Oncotarget. 2017 Feb 7;8(6):9399-409.

37. Barro M, Ruiz F, Hurlé MA. Kappa-opioid receptor mediated antinociception in rats is dependent on the functional state of dihydropyridine-sensitive calcium channels. Brain Res. 1995 Feb 20;672(1-2):148-52.

38. Xiao YF, Huang L, Morgan JP. Cytochrome P450: a novel system modulating Ca2+ channels and contraction in mammalian heart cells. J Physiol. 1998 May 1;508 ( Pt 3)(Pt 3):777-92.

39. Xiao YF. Cyclic AMP-dependent modulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ and transient outward K+ channel activities by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2007 Jan;82(1-4):11-8.

40. Patapoutian A, Tate S, Woolf CJ. Transient receptor potential channels: targeting pain at the source. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009 Jan;8(1):55-68.

41. Nilius B, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T. TRPV4 calcium entry channel: a paradigm for gating diversity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004 Feb;286(2):C195-205.

42. Watanabe H, Vriens J, Prenen J, Droogmans G, Voets T, Nilius B. Anandamide and arachidonic acid use epoxyeicosatrienoic acids to activate TRPV4 channels. Nature. 2003 Jul 24;424(6947):434-8.

43. Alessandri-Haber N, Yeh JJ, Boyd AE, Parada CA, Chen X, Reichling DB, et al. Hypotonicity induces TRPV4-mediated nociception in rat. Neuron. 2003 Jul 31;39(3):497-511.

44. Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ Res. 2005 Dec 9;97(12):1270-9.

45. Sisignano M, Park CK, Angioni C, Zhang DD, von Hehn C, Cobos EJ, et al. 5,6-EET is released upon neuronal activity and induces mechanical pain hypersensitivity via TRPA1 on central afferent terminals. J Neurosci. 2012 May 2;32(18):6364-72.