Abstract

Rathke cleft cysts (RCC) are the embryological remnants of the pars intermedia within the Rathke’s pouch, and they represent the benign end of a spectrum of lesions originating from this region. RCCs are commonly small asymptomatic lesion; however, they often attain large size and exert mass effect on surrounding vital neurovascular structures, and hence become symptomatic. RCCs are the target of transsphenoidal surgery when symptomatic; however, surgical management of RCC is challenging, because aggressive resection may carry a high risk of complications - commonly diabetes insipidus (DI), due to the embryological proximity to the neurohypophysis – whereas sub-optimal resection may result in higher rates of cyst recurrence. In this commentary, we highlight nuances in diagnosis, and our philosophy to optimize surgical treatment of RCCs.

Keywords

Rathke cleft cyst, Cystic pituitary lesions, Cystic sellar lesions, Endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery, Diagnosis

Introduction

Rathke cleft cyst (RCC) is a non-neoplastic lesion representing the embryological remnants of the pars intermedia within the Rathke’s pouch. It was first described by Lushka, in 1860, as “an epithelial area in the capsule of the human hypophysis that represents the oral mucosa” [1-3]. RCCs represent the benign end of a spectrum of lesions originating from Rathke’s cleft; craniopharyngiomas represent the more aggressive lesions related to this region [4-6]. The cyst contents vary, but are predominantly thick yellowish mucinous fluid, and the cyst wall is typically lined by simple ciliated cuboidal or columnar epithelium.

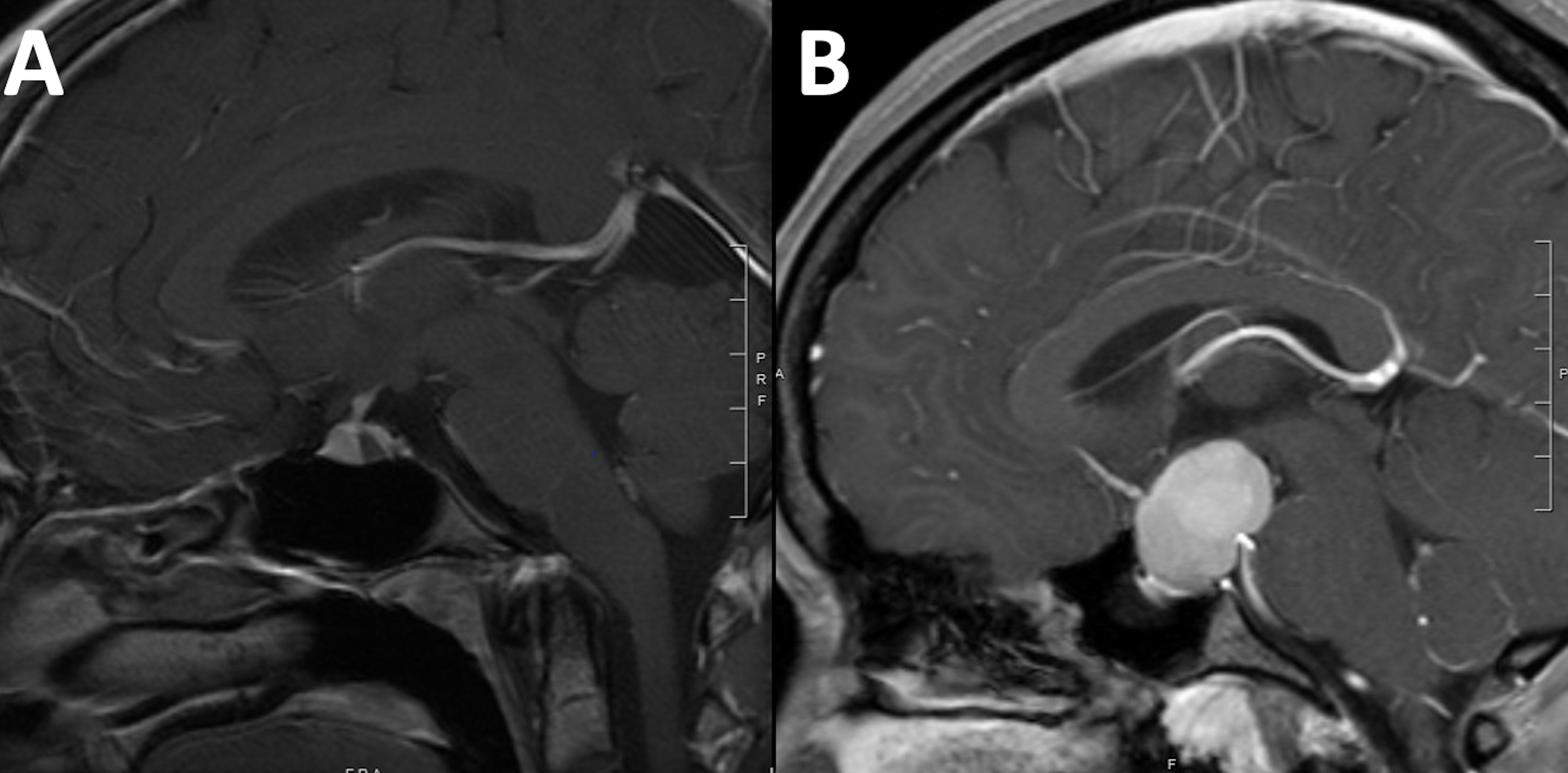

RCCs account for less than 1% of all intracranial masses [1,4-10]. Nevertheless, with the advent of modern diagnostic imaging modalities, RCCs are increasingly encountered as incidental findings during evaluation for unrelated clinical presentations [11]. RCCs are commonly small asymptomatic lesion; however, they often attain large size and exert mass effect on surrounding vital neurovascular structures, and hence become symptomatic. The most common clinical presentations include headache [6,12], vision loss, and endocrine dysfunction [4,6,10,13]. The diagnosis of RCCs is often challenging as they may resemble other cystic sellar lesions, including cystic pituitary adenomas, craniopharyngiomas, and arachnoid cysts (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Brain MRI T1WI sagittal view with intravenous Gadolinium contrast demonstrating different configurations of RCC. The typical configuration (A) is an ovoid intrasellar cyst that is located in the area of the intermediate lobe within the pituitary gland. Larger cysts (b) may attain different shapes and may resemble other lesions such as pituitary adenoma.

In the last few decades, endoscopic transsphenoidal surgery has become the gold standard for surgical management of symptomatic RCCs. The main goal of surgical intervention is to alleviate the symptoms; however, surgical management of RCC is challenging, because aggressive resection may carry a high risk of complications - commonly diabetes insipidus (DI), due to the embryological proximity to the neurohypophysis – whereas sub-optimal resection may result in higher rates of cyst recurrence. In this commentary, we highlight nuances in diagnosis, and our philosophy to optimize surgical treatment of RCCs.

Clinical and Radiographic Diagnosis of RCC

The age at presentation is variable; however, RCCs typically present in the 4th and 5th decades, with a marked female preponderance (approximately 2:1). Most patients with RCCs are asymptomatic, and only a small proportion of RCCs may exert mass effect on adjacent structures. The commonly reported symptoms are headache (45-85% of patients), visual changes (30-50%), and endocrinopathies including hypopituitarism and/or hyperprolactinemia (30-60%) [5,10,13-19]. The headache is most commonly chronic; however, different variants were noted, including episodic, migraine-like, tension-like, or acute onset headaches [6,13].

Typically, RCC is visualized on MRI as an ovoid or spherical cyst, that is located in the area of the intermediate lobe within the pituitary gland, inferior and usually anterior to the insertion of the pituitary infundibulum. The pattern of displacement of the pituitary infundibulum could reliably predict the location of the cyst. In RCC, the pituitary infundibulum is anteriorly displaced, in contrast to what is typically seen in lesions of the anterior lobe, which displace the stalk posteriorly. Larger cysts may demonstrate suprasellar extension, and may resemble other sellar lesions, such as cystic pituitary adenoma, craniopharyngioma, or arachnoid cyst [20]. On histopathologic examination, identification of simple or pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelial lining is the primary feature that distinguishes RCC from other types of cystic pituitary lesions.

Surgical Philosophy for the Management of RCC

The data in the pertinent literature support the efficacy of transsphenoidal surgical management of these lesions, given the high frequency of symptom relief and low complication rate. Nonetheless, the philosophy behind the optimal surgical approach to RCCs represents a significant controversy. Some clinicians advocate for a radical resection with total removal of the cyst wall; however, others recommend a more conservative approach with surgical fenestration of the cyst and biopsy of the cyst wall [7,16-19,21-24]. Each of these methods carries its pros and cons; a radical resection of the cyst wall is associated with lower rates of recurrence, however, with high rates of complications, namely CSF leak, and damage to the anterior and posterior lobes of the pituitary gland resulting in hypopituitarism and/or DI from damage to the infundibulum and its vascular supply. On the other end of the spectrum, suboptimal evacuation of the cyst contents through a fenestration of the cyst wall is associated with higher rates of cyst recurrence.

Our surgical philosophy is to approach RCCs in a conservative surgical fashion, designed to preserve normal pituitary function, and to minimize the risk of permanent DI, while achieving the maximal feasible resection, with a low rate of surgery-related complications. This surgical philosophy represents the pearls of several decades of experience in more than 6000 cases with sellar pathologies operated upon by the senior author (ERL).

During the preoperative evaluation, it is crucial to consider the patient’s age, gender, desire for fertility, pituitary hormonal status, and the severity of symptoms, as these factors help tailor the approach for each individual patient. Our surgical objectives are to achieve the optimum evacuation of the cyst contents through a careful dural opening, and meticulous sampling of the cyst wall tissue as safely feasible, while preserving the pituitary stalk and as much normal pituitary tissue as possible. A vertical or an inverted T dural incision for exposure and evacuation of the cyst contents prevents unnecessary damage to the compressed normal pituitary gland. Intraoperative surgical manipulation and the extent of safe resection of the cyst wall depend on many factors, including the nature and extent of the cyst contents, integrity and strength of the cyst wall, and the degree of adherence of the cyst wall to surrounding structures, such as the pituitary gland, stalk, and infundibulum, diaphragma sellae. We often fill the empty cyst cavity with Gelfoam® (Pfizer) to eliminate dead space, and the bony sellar floor is typically left with no bony or other reconstruction to provide the cyst with a pathway for drainage. Should CSF leak be encountered intraoperatively, an abdominal fat graft, harvested through a small sub-umbilical incision, is useful.

This surgical strategy has been proven to provide a balance between achieving an excellent clinical outcome, coupled with fewer complications as well as relatively low recurrence rates. In a recent publication by the authors [25] addressing the complications and outcomes in a contemporary series of patients with RCC, 84% of patients experienced improvement in the frequency and/or severity of headache, and 74% had improvement of their preoperative vision loss. The reported complications included permanent DI (4.9%), SIADH (5.8%), epistaxis (5.8%), postoperative infection (2.9%), postoperative CSF leak (<1%), intrasellar hematoma (<1%,), and a small right thalamic stroke (<1%). There were no neural or major vascular intraoperative complications. There was no surgery related mortality nor permanent neurological deficit in the series. The reported recurrence rate in the series was 5%.

Conclusion

The philosophy behind a surgical approach to Rathke cleft cysts represents a controversy. The authors’ philosophy of a conservative surgical approach has proven effective to preserve normal pituitary function, and avoid DI, while achieving the maximal feasible reduction in mass effect and limiting recurrence. Adequate evacuation of the cyst contents and meticulous sampling of the cyst wall, when possible, for histopathological diagnosis are crucial.

References

2. Shanklin WM. The incidence and distribution of cilia in the human pituitary with a description of micro-follicular cysts derived from Rathke’s cleft. Cells Tissues Organs. 1950;11(2-3):361-82.

3. Fager CA, Carter H. Intrasellar epithelial cysts. Journal of Neurosurgery. 1966 Jan 1;24(1):77-81.

4. Zada G. Rathke cleft cysts: a review of clinical and surgical management. Neurosurgical Focus. 2011 Jul 1;31(1):E1.

5. Aho CJ, Liu C, Zelman V, Couldwell WT, Weiss MH. Surgical outcomes in 118 patients with Rathke cleft cysts. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2005 Feb 1;102(2):189-93.

6. Cote DJ, Besasie BD, Hulou MM, Yan SC, Smith TR, Laws ER. Transsphenoidal surgery for Rathke’s cleft cyst can reduce headache severity and frequency. Pituitary. 2016 Feb;19(1):57-64.

7. Laws ER, Kanter AS. Rathke cleft cysts. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2004 Oct 1;101(4):571-2.

8. Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Lillehei KO, Stears JC. The pathologic, surgical, and MR spectrum of Rathke cleft cysts. Surgical Neurology. 1995 Jul 1;44(1):19-26.

9. Teramoto A, Hirakawa K, Sanno N, Osamura Y. Incidental pituitary lesions in 1,000 unselected autopsy specimens. Radiology. 1994 Oct;193(1):161-4.

10. Kanter AS, Sansur CA, John Jr A, Edward Jr R. Rathke’s cleft cysts. Pituitary Surgery-A Modern Approach. 2006;34:127-57.

11. Nishioka H, Haraoka J, Izawa H, Ikeda Y. Magnetic resonance imaging, clinical manifestations, and management of Rathke's cleft cyst. Clinical Endocrinology. 2006 Feb;64(2):184-8.

12. Madhok R, Prevedello DM, Gardner P, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Kassam AB. Endoscopic endonasal resection of Rathke cleft cysts: clinical outcomes and surgical nuances. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2010 Jun 1;112(6):1333-9.

13. Rizzoli P, Iuliano S, Weizenbaum E, Laws E. Headache in patients with pituitary lesions: a longitudinal cohort study. Neurosurgery. 2016 Mar 1;78(3):316-23.

14. Penn DL, Laws ER Jr. Rathke Cleft cyst surgery: Indications, outcomes, and complications. In: Little AS, Mooney MA (eds.). Controversies in Skull Base Surgery. Thieme Publishers New York. 2019; 143-148.

15. Cote DJ, Iuliano SL, Catalino MP, Laws ER. Optimizing pre-, intra-, and postoperative management of patients with sellar pathology undergoing transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgical Focus. 2020 Jun 1;48(6):E2.

16. Lillehei KO, Widdel L, Astete CA, Wierman ME, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Kerr JM. Transsphenoidal resection of 82 Rathke cleft cysts: limited value of alcohol cauterization in reducing recurrence rates. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2011 Feb 1;114(2):310-7.

17. Lin M, Wedemeyer MA, Bradley D, Donoho DA, Fredrickson VL, Weiss MH, et al. Long-term surgical outcomes following transsphenoidal surgery in patients with Rathke’s cleft cysts. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2018 May 18;130(3):831-7.

18. Benveniste RJ, King WA, Walsh J, Lee JS, Naidich TP, Post KD. Surgery for Rathke cleft cysts: technical considerations and outcomes. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2004 Oct 1;101(4):577-84.

19. Wait SD, Garrett MP, Little AS, Killory BD, White WL. Endocrinopathy, vision, headache, and recurrence after transsphenoidal surgery for Rathke cleft cysts. Neurosurgery. 2010 Sep 1;67(3):837-43.

20. Tavakol S, Catalino MP, Cote DJ, Boles X, Laws Jr ER, Bi WL. Cyst Type Differentiates Rathke Cleft Cysts From Cystic Pituitary Adenomas. Frontiers in Oncology. 2021;11.

21. Laws ER. Endoscopic surgery for cystic lesions of the pituitary region. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2008 Dec;4(12):662-663.

22. Barkhoudarian G, Zada G, Laws ER. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for nonadenomatous sellar/parasellar lesions. World Neurosurgery. 2014 Dec 1;82(6):S138-46.

23. Cavallo LM, Prevedello D, Esposito F, Laws ER, Dusick JR, Messina A, et al. The role of the endoscope in the transsphenoidal management of cystic lesions of the sellar region. Neurosurgical Review. 2008 Jan;31(1):55-64.

24. Zhang X, Yang J, Huang Y, Liu Y, Chen L, Chen F, et al. Endoscopic Endonasal Resection of Symptomatic Rathke Cleft Cysts: Total Resection or Partial Resection. Frontiers in Neurology. 2021;12.

25. Montaser AS, Catalino MP, Laws ER. Professor Rathke’s gift to neurosurgery: the cyst, its diagnosis, surgical management, and outcomes. Pituitary. 2021 Oct;24(5):787-796