Background

Acute pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling actual or potential tissue damage as a result of a surgical procedure, physical trauma, or as a consequence of a medical condition [1]. The prevalence of moderate-severe pain, defined as pain which significantly interferes with daily living activities, ranges between 27% and 66% in hospitalized pediatric patients and remains inconsistent even in those institutions with excellent resources and good reputations [2,3]. Moderate-severe pain may be a source of distress for not only the patient but also for family and health care providers. There are significant implications of inadequately-treated acute pain which might persist for months or years after the initial intervention with a potential to transition into chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) [4]. CPSP is defined as clinical discomfort that lasts more than 2 months post-surgery without other causes of pain or pain from a chronic condition preceding the surgery [5]. CPSP, being associated with poorer surgical outcomes and decreased ability to return to expected functioning, can lead to significant morbidity and has a significant impact on quality of life [6]. With the understanding that interventions in the acute inpatient setting can have profound implications later, current challenges to the delivery of optimal pain management must be explored to provide practical and actionable recommendations that can be utilized across a variety of inpatient settings. These action items will facilitate a more equitable and consistent delivery of pain management for every pediatric patient.

What We have Learned So Far

Many advances in pediatric pain management have been made over the past 30 years. In a recent article, Professor Lönnqvist summarized the numerous milestones that have been responsible for elevating pediatric pain management to a specialty with immense impact to minimize suffering [7]. There are a multitude of strategies for the treatment of acute pain that have been identified over the years [8-11]. While it is known that these strategies contribute to optimal pain management, it remains challenging to consistently implement them across various hospital settings [12,13]. For example, inconsistent use or omission of non-pharmacologic strategies and first-line agents such as acetaminophen/paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) might result in higher self-reported pain scores. In addition, failure to plan for medication side effects contributes to patient discomfort, increasing morbidity and economic burden. Here the goal is to take a pre-emptive but safe approach to the treatment of acute pain and symptoms. While some providers do have robust mechanisms in place for consistent use of comprehensive pain management protocols, there currently is not a universally-applied tool. The result may be the unintentional exclusion of beneficial modalities, simple strategies that are easily applied and can improve patient comfort and sense of well-being. Attention to non-pharmacologic strategies such as application of ice, heat, and comfort positioning is often forgotten. Modalities such as child life, pet therapy, music and aroma-therapies may be excluded with the misconception that these do not represent true pain management strategies. Providers may not feel these recommendations are within their purview, better left to suggestion by the nursing providers and child life specialists. The result is disjointed care which jeopardizes the patients’ and families’ acceptance that these are effective strategies and may be even more important than medication per se. We have also learned the importance of the biopsychosocial approach to pain that takes into consideration the negative states of mind, such as helplessness and hopelessness, and that these behaviors can have a significant impact on pain experience [14]. Furthermore, rather than focusing on pain scores alone, the ultimate intention of pain management (improved functional mobility and return to activities of daily living) should be more consistently reinforced [15]. Steady attention to this biopsychosocial approach to acute pain by every physician and healthcare provider would indicate to patients that these are effective modalities. In addition, this gesture could serve to address the pain-related treatment disparities based on gender, race, age, as well as the idiosyncratic practices of physicians in the management of acute pain [16,17].

Challenges

Although pediatric management has come a long way, there are a number of factors that might drive idiosyncratic decisions and inequities of optimal pain management. These challenges involve physicians, nursing personnel, the patient/family, and the organizational institutions and are outlined below [18].

Adequate pain education

The widespread lack of pain education in medical school and residency programs has been identified as a significant global problem [19]. Physicians are taught a baseline curriculum of pain management but may not be as well versed in some of the finer nuances of pain management that is imperative for all providers [20]. For example, the use of first-line (basic, simple) analgesics such as acetaminophen and NSAIDs are often not optimized, even in those patients with expected intense pain having no contraindication and receiving opioids. This fact alone can result in the inappropriate use of opioids, such as increasing the dose or the frequency earlier than expected based on pain score or perceived discomfort. Similarly, the consistent offering and use of non-pharmacologic strategies such as ice, heat, therapeutic play, distraction techniques, physical therapy, pet therapy and others may be lacking. These modalities may in reality improve well-being and quality of life, and facilitate the patient’s rapid return to baseline functioning. These are simple treatments to teach and execute and may result in the decreased need for pain medications [17].

The individual practices of nursing personnel and prescribers may have a significant impact on the practical administration of medications to the patient with pain. Nurses typically spend more time at the bedside than other healthcare providers and are often staunch advocates for optimal pain management. However, differing approaches to the medication scheduling can have a significant impact on the quality of the pain experience. Approach to the PRN (pro re nata - as needed) prescription of pain medications may result in some nursing providers being proactive, offering the medication on a preemptive basis. Others may be reactive and wait for increased pain intensity and patient request prior to administration [21]. The former approach results in a more consistent therapeutic plasma level of medication and the potential for improved pain management [22]. In the patient with moderate-severe pain, waiting to administer a medication until it is requested may result in wide swings in pain intensity, causing distress. Similarly, prescribers may not have made a plan for the management of breakthrough pain, leaving the patient in the difficult situation of worsening pain. The goal is to put the patient’s and family’s mind at ease and gain trust.

Family & patient factors

An additional barrier to optimal pain management may be the patient/family themselves. Patients may not have realistic expectations with regard to the pain they might experience from a surgical procedure or the effort that might be required of them to facilitate their functional recovery. In addition, they may have had negative experience with pain in the past that might have a significant impact on their ability to cope in the current setting [23]. On the other hand, there may also be misconceptions that pain is something to be endured, which might lead to a patient’s hesitancy to honestly communicate their experiences [18]. Although setting appropriate expectations prior to a surgical intervention is the responsibility of the physician, many patients may not be aware of how to best prepare themselves for the sequelae of a surgical procedure. Patients should be encouraged to be good advocates for themselves, to ask questions so their concerns are validated, and improve their self-efficacy towards functional recovery.

Organizational challenges

Pain, defined as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’ does not readily lend itself to objective measure [1]. Alternatively, due to the complex nature of pain, self-report measures may be inaccurate and are by definition subjective in nature. It is often difficult for providers and patients to distinguish between the nociceptive contribution to pain compared with the other sources of ‘discomfort’, such as psychological pain, anxiety, social pain, and poor sleep [10]. Just how to measure effective pain management is exceptionally challenging but most would agree that the pain score alone should not be a measure of success [24]. Moreover, patient satisfaction scores are not necessarily indicators of quality of care delivered and have several confounding factors [25].

A number of restrictions within the organization may inadvertently hinder pain management efforts. These include lack of accountability for pain management, local culture, and the willingness to be self-reflective regarding quality and outcomes [18,26]. Local culture may encourage residents and trainees to ‘learn’ pain management by actively managing patients themselves rather than involving the acute pain services. Unfortunately, this attitude often results in sub-optimal care of patients. Trainees may not be given appropriate guidance, may be discouraged from seeking help, and are encouraged to use their own critical thinking skills that may be beyond the scope of their knowledge. This scenario may be all too familiar to the nurses who spend the most time at bedside, are excellent advocates, but may be unable to afford change regarding physician practices. Furthermore, idiosyncratic decisions and inconsistent use of non-pharmacologic strategies make it exceedingly difficult to make comparisons among patients. Without the potential for high-level oversight, individual silos regarding pain management efforts develop leading to variable outcomes.

Impact of the opioid crisis

If suboptimal pain management was a problem prior to 2017, the formal acknowledgement of the opioid crisis has certainly compounded the issue. While the spirit of opioid stewardship is to minimize the availability of opioids for potential misuse and reduce risk, the result has been an inadvertent disparity of another kind; patients with legitimate pain from a major/complex surgical procedure that are under-prescribed or not prescribed opioids. While 2002 was the year of ‘Pain as the Fifth Vital Sign’ and gave the permission to treat with opioids, 2017 was the year that seemingly gave prescribers the permission to avoid opioid prescriptions. Providers now feel scrutinized for opioid prescriptions and may avoid them for fear of losing their medical licenses. The challenges described above have been augmented by the pitfalls of self-reported pain and observational scores, and a real problem with polypharmacy and drug diversion [27,28]. This puts the patient-physician relationship in serious jeopardy as we strive to work in the best interest of the patient, balancing risks and benefits of opioid use. Unfortunately, the complexity of the pain experience and the lack of a systematic approach to pain management has made the impact of opioid-prescribing restrictions exceedingly difficult to measure. This has resulted in exacerbation of pre-existing disparities [29]. While institutions have attempted to address opioid stewardship, some recommendations fall short with the omission of the holistic and comprehensive modalities, valuable components of acute pain care [30]. Rather than swinging from one pole to another, the optimal solution lies in the middle, and must take into consideration the risk of not prescribing opioids for procedures or conditions associated with intense pain.

Recommendations

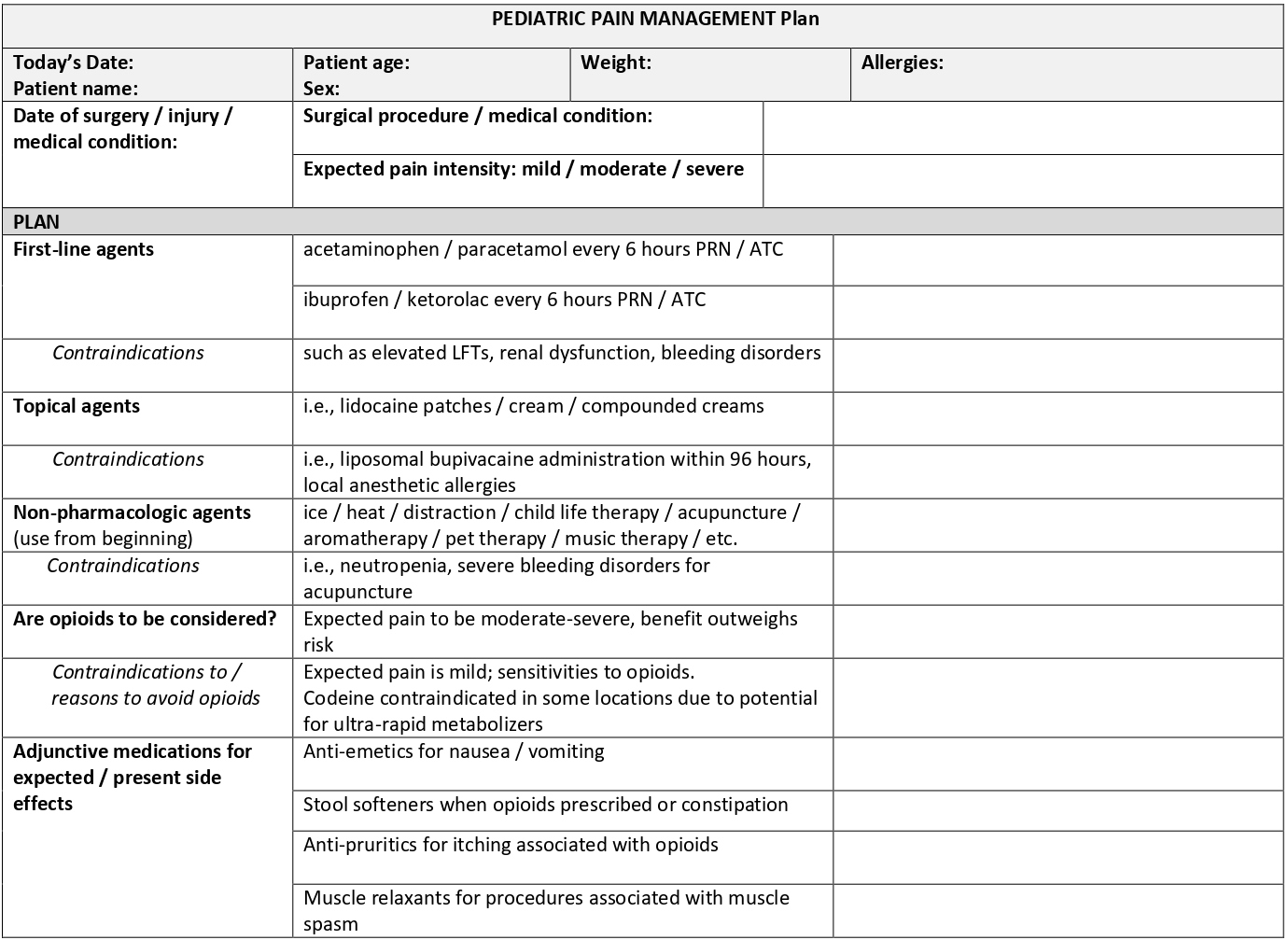

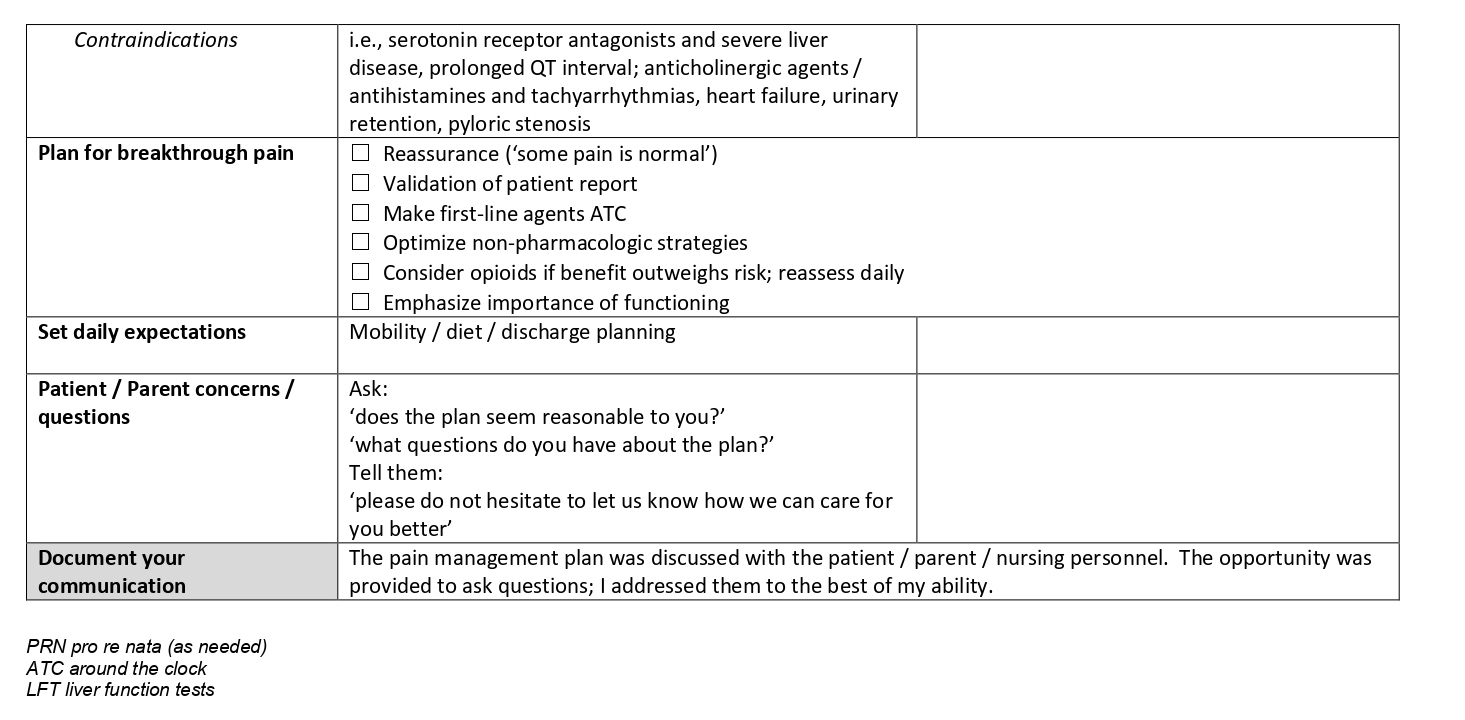

While there are simply not enough pediatric pain-trained specialists to care for the entire pediatric population, it is well within the purview of all physicians to have a basic understanding of the practicalities of acute pain management and the ability to execute an initial plan of a multimodal nature [31]. The challenges described above can be partially mitigated with a more systematic approach to pain management. A comprehensive plan would consider the use of non-opioid, non-pharmacologic, topical and opioid therapies as appropriate for all patients to address the various mechanisms by which pain is experienced [10]. Understanding the risk factors for CPSP sets the stage for optimal management of acute pain. While the presence of baseline pain cannot necessarily be modified, several other risk factors are amenable to intervention such as child anxiety, pain self-efficacy, and parental pain catastrophizing [32]. Pediatric pain management has significantly improved over the years. However, there is plenty more to be done. Although there may be efforts in place to develop new medications, it is imperative that we find more reproducible, methods to consistently implement existing modalities available in any given location. Taking the lead from the aviation industry as anesthesiologists have done in the past, this systematic approach with the use of a checklist of sorts could be utilized to remind the provider of the numerous modalities to be considered [33] (Figure 1). Assessment of pain is beyond the scope of this article and is purposefully omitted from the checklist. The interested reader is encouraged to review the available literature on the topic [34].

Figure 1: A Pediatric Pain Management Plan checklist to promote systematic approach to pain management and facilitate documentation in the electronic medical record.

Initiatives are currently underway to better classify surgical procedures and medical conditions based on the levels of expected pain intensity [35,36]. While the patient’s individual experience may vary, providers can benefit from their collective knowledge as to the typical patient experience regarding pain and symptoms for a given condition. Thus, the work can begin to develop a framework to an effective multimodal care plan. Acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents should be considered first-line agents in the treatment of pain from surgical and medical conditions unless contraindications exist. Other non-opioid therapies such as topical creams, gabapentinoids, muscle relaxants, antispasmodics should be considered if appropriate based on the character of expected pain. These medications should be considered from the very beginning of treatment, rather than waiting on the results of other modalities. Similarly, non-pharmacologic strategies are often low risk and need to be considered from an early stage of treatment. While not considered first-line agents, opioids should be considered if moderate to severe pain is expected. Appropriate use of opioids early in the post-operative period might decrease or eliminate the need for an opioid prescription after hospital discharge. This might lead to earlier functional improvement if pain is better managed during the period of mobility in the early postoperative period. Risks and benefits of opioid use must be balanced and the patient must be expected to make appropriate progress with functional gains during opioid therapy. Moreover, providers should anticipate the expected side effects of medications such as pruritus, nausea, vomiting, and constipation and make proactive plans. In some hospital settings, there may be a delay in delivering medication to the patient if the pharmacy is not prepared to dispense a medication in an urgent fashion, which might increase patient distress and morbidity.

Clear communication of the plan with the patient, family, as well as nursing personnel is imperative to assure all stakeholders are actively informed and function as a collaborative team. Presenting the plan and asserting that these strategies have the potential to decrease the requirement for opioid medications will reassure the patient. Assessing the response to treatment on a regular basis and having the flexibility to alter the plan if needed will ensure an individualized plan balancing risks and benefits. Providers would benefit from increasing their own comfort engaging patients and their family in brief conversations about pain, when appropriate. The cognitive tool described in this manuscript can provide a foundation for discussion. Patient dissatisfaction evolves in part from the patient feeling misunderstood or invalidated with regard to their pain. The provider who fails to engage in a conversation about a patient’s concerns may become mistrusted. Finally, complete documentation in the medical record is instrumental in the success of the plan and sets the stage for being flexible should changes in the plan be needed. The Joint Commission has published their revised standards in order to minimize disparities in pain management [37].

Looking to the future

Universal use of a systematic approach to pain management might be the next logical step to facilitate more robust comparisons of pain management strategies across populations. This practice could serve as a pivotal paradigm shift to encourage more robust comprehensive pain management education for our medical trainees and staff. In addition, institutions could keep providers accountable by assessing compliance of use of a systematic approach, particularly for those patients that continue to report the highest pain scores. More research is needed to assess the impact of such a practice. With the widespread use of the smartphone and the explosion in the number of medical apps currently on the market, it is only a matter of time before a more sophisticated tool will become available to encourage a systematic approach to acute pain management.

Although there have been great improvements in the science and implementation of acute pain care over the past 30 years, we are at a crossroads as to how best address the problem of inadequately-treated postoperative pain. In an effort to make measureable improvements in the assessment and delivery of pain management, finding a way to consistently implement the currently available strategies (pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic) at the bedside will have the greatest impact.

A call to action

- Take a systematic approach to all patients when creating a pain management plan using the template included (Figure 1)

- Base the use of therapies and opioids on the expected pain intensity for a given surgical procedure, trauma or medical condition

- Anticipate side effects based on demographics/procedure and make treatments available PRN

- Clearly communicate and document your plan, including contraindications for certain therapies; Figure 1 can serve as a documentation template in the medical record

- Reassess the efficacy of your plan on a regular basis and make changes, as needed

- Consult a pediatric pain management specialist if additional consultation is warranted, particularly if chronic pain is present

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Christina Pabelick MD, Professor of Anesthesiology and Physiology, Mayo Clinic Rochester for her unwavering support and critical review of the final manuscript.

References

2. Groenewald CB, Rabbitts JA, Schroeder DR, Harrison TE. Prevalence of moderate–severe pain in hospitalized children. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2012 Jul;22(7):661-8.

3. Harrison D, Joly C, Chretien C, Cochrane S, Ellis J, Lamontagne C, et al. Pain prevalence in a pediatric hospital: raising awareness during Pain Awareness Week. Pain Research and Management. 2014 Jan 13; 19(1):e24-30.

4. Gan TJ. Poorly controlled postoperative pain: prevalence, consequences, and prevention. Journal of Pain Research. 2017;10:2287.

5. Richebé P, Capdevila X, Rivat C. Persistent postsurgical pain: pathophysiology and preventative pharmacologic considerations. Anesthesiology. 2018 Sep;129(3):590-607.

6. Macrae WA, Davies HT. Chronic postsurgical pain. In: Crombie IK ed. Epidemiology of Pain. Seattle: IASP Press 1999:125-42.

7. Lönnqvist PA. What has happened since the First World Congress on Pediatric Pain in 1988? The past, the present and the future. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2020 Nov;86(11):1205-13.

8. Cravero JP, Agarwal R, Berde C, Birmingham P, Coté CJ, Galinkin J, et al. The Society for Pediatric Anesthesia recommendations for the use of opioids in children during the perioperative period. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2019 Jun;29(6):547-71.

9. Greco C, Berde C. Pain management for the hospitalized pediatric patient. Pediatric Clinics. 2005 Aug 1;52(4):995-1027.

10. Friedrichsdorf SJ, Goubert L. Pediatric pain treatment and prevention for hospitalized children. Pain Reports. 2020 Jan;5(1).

11. Gai N, Naser B, Hanley J, Peliowski A, Hayes J, Aoyama K. A practical guide to acute pain management in children. Journal of Anesthesia. 2020 Jun;34(3):421-33.

12. Kozlowski LJ, Kost-Byerly S, Colantuoni E, Thompson CB, Vasquenza KJ, Rothman SK, et al. Pain prevalence, intensity, assessment and management in a hospitalized pediatric population. Pain Management Nursing. 2014 Mar 1;15(1):22-35.

13. Twycross A, Collis S. How well is acute pain in children managed? A snapshot in one English hospital. Pain Management Nursing. 2013 Dec 1;14(4):e204-15.

14. Gatchel RJ, Howard KJ. The biopsychosocial approach. Practical Pain Management. 2020;8(4).

15. The Pain scale chart: What it really means. ProHealth, Inc. Carpinteria, CA. 2015. [May 18, 2019; November 27, 2020]. Prohealth.com/library/what-the-pain-scale-really-means-34982.

16. Lee P, Le Saux M, Siegel R, Goyal M, Chen C, Ma Y, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the management of acute pain in US emergency departments: meta-analysis and systematic review. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2019 Sep 1;37(9):1770-7.

17. Tick H, Nielsen A, Pelletier KR, Bonakdar R, Simmons S, Glick R, et al. Evidence-based nonpharmacologic strategies for comprehensive pain care: the consortium pain task force white paper. Explore. 2018 May 1;14(3):177-211.

18. Carr E. Barriers to effective pain management. Journal of Perioperative Practice. 2007 May;17(5):200-8.

19. Vadivelu N, Mitra S, Hines R, Elia M, Rosenquist RW. Acute pain in undergraduate medical education: an unfinished chapter! Pain Practice. 2012 Nov;12(8):663-71.

20. Shipton EE, Bate F, Garrick R, Steketee C, Shipton EA, Visser EJ. Systematic review of pain medicine content, teaching, and assessment in medical school curricula internationally. Pain and Therapy. 2018 Dec;7(2):139-61.

21. Denness KJ, Carr EC, Seneviratne C, Rae JM. Factors influencing orthopedic nurses’ pain management: A focused ethnography. Canadian Journal of Pain. 2017 Jan 1;1(1):226-36.

22. Becker DE. Pain management: Part 1: Managing acute and postoperative dental pain. Anesthesia Progress. 2010;57(2):67-79.

23. Draft Report on Pain Management Best Practices: Updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. hhs.gov. Dec 28, 2018. https://www.hhs.gov/ash/

24. Jensen MP, Tomé-Pires C, de la Vega R, Galán S, Solé E, Miró J. What determines whether a pain is rated as mild, moderate, or severe? The importance of pain beliefs and pain interference. The Clinical Journal of Pain. 2017 May;33(5):414

25. Carlson J, Youngblood R, Dalton JA, Blau W, Lindley C. Is patient satisfaction a legitimate outcome of pain management?. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2003 Mar 1;25(3):264-75.

26. Stephens P. May 6, 2019. Why doctors crash planes. Med PageToday. [11/27/2020]. https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2019/05/why-doctors-crash-planes.html

27. Rabbitts JA, Aaron RV, Zempsky WT, Palermo TM. Validation of the youth acute pain functional ability questionnaire in children and adolescents undergoing inpatient surgery. The Journal of Pain. 2017 Oct 1;18(10):1209-15.

28. Dineen KK, DuBois JM. Between a rock and a hard place: can physicians prescribe opioids to treat pain adequately while avoiding legal sanction? American Journal of Law & Medicine. 2016 Mar;42(1):7-52.

29. Erskine A, Wiffen PJ, Conlon JA. As required versus fixed schedule analgesic administration for postoperative pain in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015(2).

30. Gazelka HM, Clements CM, Cunningham JL, Geyer HL, Lovely JK, Olson CL, et al. An institutional approach to managing the opioid crisis. In: Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2020 May 1 (Vol. 95, No. 5, pp. 968-981). Elsevier.

31. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington DC: National Academies Press (US); 2011. 4, Education Challenges. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK92522/

32. Rabbitts JA, Fisher E, Rosenbloom BN, Palermo TM. Prevalence and predictors of chronic postsurgical pain in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Pain. 2017 Jun 1;18(6):605-14.

33. Chopra V, Bovill JG, Spierdijk J. Checklists: aviation shows the way to safer anesthesia. Anesthesia Patient Safety Newsletter. 1991; 6:26-9.

34. Hauer J, Jones BL, Poplack DG, Armsby C. Evaluation and management of pain in children. Up to Date. 2014 Aug.

35. Joshi GP, Kehlet H. Postoperative pain management in the era of ERAS: an overview. Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology. 2019 Sep 1;33(3):259-67.

36. Vittinghoff M, Lönnqvist PA, Mossetti V, Heschl S, Simic D, Colovic V, et al. Postoperative pain management in children: Guidance from the pain committee of the European Society for Paediatric Anaesthesiology (ESPA Pain Management Ladder Initiative). Pediatric Anesthesia. 2018 Jun;28(6):493-506.

37. Joint Commission enhances pain assessment and management requirements for accredited hospitals. The Joint Commission Perspectives 2017; 37(7):1-4).