Abstract

Context: Pain management in elderly trauma patients is complicated by age-related physiological changes, comorbidities, and limited treatment resources. In low-resource settings such as southern Puerto Rico, emergency department (ED) pain management practices remain understudied.

Objectives: To describe patterns of analgesic use, including multimodal opioid-sparing strategies, and evaluate their association with ED length of stay in elderly trauma patients in a low-resource ED.

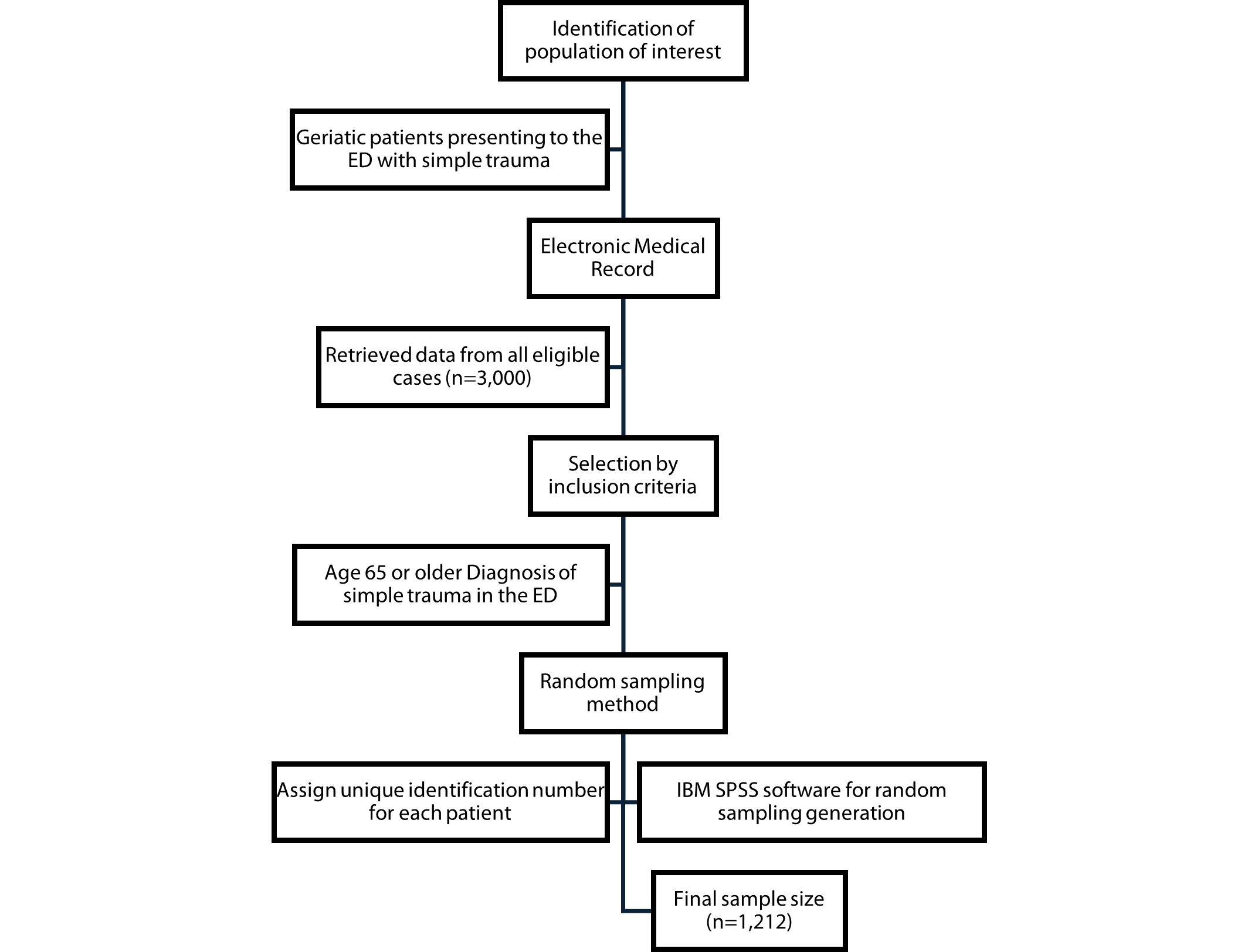

Methods: A retrospective review was conducted of 3,000 ED visits by patients aged ≥65 with simple trauma from 2022-2024. After random sampling, 1,212 patients met inclusion criteria. Data on demographics, comorbidities, injury type, analgesics administered, and ED length of stay were collected. Statistical analyses included chi-square tests, linear regression, and independent t-tests.

Results: Of the 1,212 patients, 61% were female and 86% had at least one chronic condition. Common injuries included head (34.9%), lower extremity (24%), and upper extremity (21.9%). Analgesics were administered to 79.6% of patients, with acetaminophen (41.7%) and (ketorolac) (31.3%) being the most frequently administered. Opioids were used in 4.7% of cases. Local anesthetics were administered to 18.7%. Multimodal treatment (use of ≥2 analgesic types) was administered to 15.7% of patients. Ketorolac use correlated with shorter ED stays (mean 32 minutes less, p=0.012), while opioid use correlated with longer stays (mean 1 hour 58 minutes more, p=0.012).

Conclusion: These findings underscore the importance of developing geriatric-specific, multimodal opioid-sparing pain protocols tailored to low-resource EDs and expanding training in local anesthetic techniques to optimize non-opioid analgesia and improve care in similar settings.

Keywords

Elderly, Trauma, Pain management, Emergency department, Opioid-sparing, Regional anesthesia

Key Message

This retrospective study examines pain management in elderly trauma patients in a low-resource ED. It reveals that the use of multimodal opioid-sparing analgesia is feasible even in low-resource settings, highlights underuse of local anesthetics, and underscores the need for geriatric-specific protocols and training to improve pain control and patient outcomes.

Introduction

As of 2024, adults aged 65 and older account for over 10% of the global population, nearly double the 1974 figure and still rising [1]. In the island of Puerto Rico, the proportion of older adults has increased greatly, from approximately 13% of the population being over 65 years in 2014, to 24.6% of the population in 2024. This demographic shift is reflected in emergency departments (EDs), where older adults represent a growing share of visits. In the United States, individuals aged ≥65 present to the ED more frequently than any other age group except infants under one year [2]. As the aging population expands, ensuring effective pain management in elderly patients is a critical and evolving challenge.

Acute pain is one of the most common presenting complaints in the ED [3]. Older adults experience both acute and chronic pain at high rates but are frequently undertreated. Contributing factors include communication difficulties, underreporting of symptoms, complex comorbidities, and provider bias [4]. Age-related physiologic changes and polypharmacy also increase susceptibility to adverse drug events, complicating medication choices [4–6]. Inadequate analgesia carries its own risks, including increased incidence of delirium, prolonged hospitalizations, and other pain-related complications [7]. Conversely, timely and appropriate pain control can shorten hospital stays, improve recovery, and reduce both morbidity and healthcare costs [8].

The goal of ED pain management is to provide effective relief while minimizing adverse effects, enabling either safe discharge or transition to inpatient care [9]. In past decades, efforts to improve pain recognition and treatment contributed to liberal opioid prescribing, which in turn contributed to rising rates of misuse, dependence, and opioid-related mortality [10]. As a result, emergency medicine and anesthesiology societies now emphasize stricter opioid-prescribing guidelines and recommend a multimodal approach to analgesia, incorporating two or more drugs with different mechanisms of action to optimize pain control while reducing opioid use [11].

While much of the literature on geriatric pain management is based on high-resource healthcare systems, little is known about practices in low-resource settings, particularly in regions like Puerto Rico, highlighting gaps in understanding real-world pain practices in under-resourced environments. The island lacks published data on analgesic approaches for geriatric trauma patients, where healthcare disparities, staffing shortages, and resource limitations may lead to deviations from standard pain management protocols. To address this gap, we evaluated pain management strategies for geriatric trauma patients in a tertiary care ED in southern Puerto Rico. Specifically, we examined the use of opioid and non-opioid analgesics, adherence to multimodal strategies, and potential barriers to optimal pain control. This study provides insight into real-world analgesic practices in a low-resource environment and informs efforts to improve care for vulnerable geriatric populations.

Methods

We conducted a single-center, retrospective cohort study of elderly patients who presented to the ED with simple trauma over a 3-year period (2022–2024). Data was retrieved from the center’s electronic medical records, with prior authorization obtained for record access. A total of 3,000 cases met the inclusion criteria. We used IBM SPSS to perform random sampling from the eligible records to minimize selection bias and ensure a representative sample. This resulted in a final study sample of 1,212 patients. The inclusion criteria were patients 65 years or older that presented to the ED with simple trauma. Exclusion criteria included patients with chronic pain conditions or those classified as polytraumatized, defined as having multiple severe injuries. Figure 1 outlines the selection process and inclusion flow. Data was entered into the institutional REDCap system, and analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS. Statistical methods included descriptive statistics, chi-square tests for categorical variables, linear regression analyses to assess relationships and influential factors between variables, and t-tests for comparing means between groups. The study was approved by the Ponce Health Sciences University Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol number: 2404195618).

Figure 1. Flow diagram illustrating the random sampling process used to select patients for the study.

Results

A total of 1,212 patients aged ≥65 years met inclusion criteria. Of these, 61% were female and 39% male. Most patients (86%) had at least one chronic condition. The most common comorbidities were hypertension (75.8%), diabetes mellitus (44.2%), hypothyroidism (17.5%), coronary artery disease (11.9%), chronic kidney disease (5.1%), and osteoporosis (3.9%). Neurodegenerative disorders were also present in a subset of patients, including Alzheimer’s dementia (5.6%) and other dementias (4.9%).

Injury characteristics

Among the total cohort, 961 patients (79.3%) sustained trauma to a single anatomical region, while 251 (20.7%) had injuries involving multiple areas. The most common injury site was the head (34.9%, n=423), followed by the lower extremities (24.0%, n=292) and upper extremities (21.9%, n=266). Additional injuries included shoulder (9.8%, n=119), hip (8.9%, n=108), back (8.3%, n=100), maxillofacial (6.5%, n=79), ribs (4.5%, n=55), chest (4.2%, n=51), eyes (2.1%, n=26), and pelvis (1.6%, n=19). Figure 1 outlines the patient selection process.

Analgesic administration

Overall, 79.6% of patients received at least one analgesic medication during their ED visit, while 20.4% were discharged without administration of analgesics. The most frequently administered analgesic was acetaminophen (41.7%), followed by NSAIDs (ketorolac), (31.3%), local anesthetics (18.7%), and opioids (4.7%). Multimodal analgesia, defined as the use of two or more classes of analgesics, was documented in 15.7% of cases.

Analgesic use by trauma type

Analgesic use varied by injury type. Among patients with head trauma, 224 (52.9%) received acetaminophen, and 109 (25.8%) were discharged without analgesics (both p<0.001). Lower extremity injuries were primarily treated with ketorolac (42.8%, p<0.001), with opioid use documented in only 2.4% of cases (p=0.033). A similar pattern was observed in upper extremity injuries, where 100 patients (37.6%, p=0.012) received ketorolac and 19 (7.1%, p=0.033) received opioids. Shoulder, hip, back, and other trauma types showed varying combinations of acetaminophen, ketorolac, and local anesthetics. Full analgesic distributions by trauma site and associated p-values are detailed in Table 1.

|

Trauma Type (total patients) |

Medication |

Patients treated |

P-value |

|

Head (423) |

Acetaminophen |

224 |

<0.001 |

|

NSAIDs |

49 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

108 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Morphine |

23 |

0.377 |

|

|

No analgesia |

109 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Lower Extremity (292) |

Acetaminophen |

113 |

0.225 |

|

NSAIDs |

125 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

37 |

0.002 |

|

|

Morphine |

7 |

0.033 |

|

|

No analgesia |

53 |

0.278 |

|

|

Upper Extremity (266) |

Acetaminophen |

96 |

0.034 |

|

NSAIDs |

100 |

0.012 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

83 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Morphine |

19 |

0.033 |

|

|

No analgesia |

39 |

0.009 |

|

|

Shoulder (119) |

Acetaminophen |

51 |

0.796 |

|

NSAIDs |

58 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

9 |

0.001 |

|

|

Morphine |

13 |

<0.001 |

|

|

No analgesia |

11 |

0.01 |

|

|

Hip (108) |

Acetaminophen |

46 |

0.552 |

|

NSAIDs |

49 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

3 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Morphine |

8 |

0.164 |

|

|

No analgesia |

13 |

0.024 |

|

|

Back (100) |

Acetaminophen |

42 |

0.958 |

|

NSAIDs |

56 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

7 |

0.002 |

|

|

Morphine |

9 |

0.034 |

|

|

No analgesia |

7 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Ribs (55) |

Acetaminophen |

23 |

0.992 |

|

NSAIDs |

26 |

0.009 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

3 |

0.010 |

|

|

Morphine |

6 |

0.026 |

|

|

No analgesia |

5 |

0.03 |

|

|

Chest (51) |

Acetaminophen |

19 |

0.502 |

|

NSAIDs |

19 |

0.346 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

6 |

0.193 |

|

|

Morphine |

6 |

0.015 |

|

|

No analgesia |

8 |

0.395 |

|

|

Maxillofacial (79) |

Acetaminophen |

41 |

0.058 |

|

NSAIDs |

6 |

<0.001 |

|

|

Local anesthetic |

21 |

0.064 |

|

|

Morphine |

8 |

0.019 |

|

|

No analgesia |

17 |

0.795 |

Impact of analgesics on emergency department length of stay (ED LOS)

Linear regression using ED length of stay as the dependent variable revealed statistically significant associations with administration of ketorolac (p=0.023), opioids (p<0.001), and acetaminophen (p<0.001).

An independent t-test was performed to compare mean ED stay durations by medication received. Patients who received opioids spent an average of 1 hour, 58 minutes, and 21 seconds longer in the ED compared to those who did not (p=0.012). Conversely, patients treated with ketorolac spent an average of 32 minutes and 8 seconds less in the ED (p=0.012). No statistically significant differences in ED length of stay were observed for patients receiving acetaminophen or local anesthetics.

Fracture management

Fractures were identified in 208 patients (17.2%). When these were stratified by the medications administered, statistically significant relationships were found with two groups of medications. One hundred fifteen of these patients (55.3%) were treated with ketorolac (p<0.001), while only 38 (18.2%) were administered opioid medications (p<0.001). Although not statistically significant associations, it is of note that 33 (15.8%) of these patients were administered local anesthetics (p=0.245) and 87 (41.8%) received acetaminophen (p=0.980).

Discussion

This study provides novel insight into analgesic practices for geriatric trauma patients in a low-resource ED setting. Our findings highlight a relatively low rate of opioid utilization in favor of multimodal analgesia, primarily involving acetaminophen and ketorolac. Notably, opioid administration was associated with longer ED stays, while ketorolac use correlated with shorter durations. These trends reflect a conservative prescribing approach that aligns with current opioid-sparing guidelines and may be influenced by local resource constraints, patient demographics, and provider practices.

Importantly, our findings challenge the assumption that guideline-concordant pain management is unachievable in resource-limited settings. Despite constraints in staffing, medication availability, and procedural support, the ED in this study consistently employed a multimodal analgesia approach, with a clear preference for non-opioid agents. This demonstrates that adherence to contemporary pain management guidelines particularly those emphasizing opioid-sparing strategies, is feasible even outside high-resource academic or urban centers. It highlights the potential for scalable, safe, and effective geriatric pain care in similarly underserved environments.

To our knowledge, no prior studies have specifically examined geriatric trauma pain management in low-resource EDs, underscoring a significant gap in literature. Conducted in southern Puerto Rico, a region with a predominantly Hispanic and aging population, this study reflects the challenges posed by socioeconomic disadvantage, limited healthcare access, and lower healthcare literacy. These contextual factors likely shape provider decision-making and contribute to a preference for non-opioid analgesics, contrasting with higher opioid use reported in higher-resource settings such as the mainland United States [4–6,10,12].

Pain management in older adults is inherently complex due to physiological changes, polypharmacy, cognitive impairments, and comorbidities. Our data showed a female predominance (61%) in geriatric trauma cases and high rates of chronic conditions, including hypertension (75.8%) and diabetes mellitus (44.2%). Dementia, present in over 10% of patients, adds another layer of complexity, given the difficulties in pain assessment and communication. These findings are consistent with previous studies reporting similar demographic and clinical profiles in aging trauma populations [12–15].

While acetaminophen was the most frequently administered analgesic, ketorolac was also commonly used despite NSAID’s known risks in older adults. Importantly, NSAID use was associated with shorter ED stays, suggesting their utility in rapid pain relief and discharge planning. Conversely, patients who received opioids remained in the ED longer, likely reflecting the need for closer monitoring or more severe injury profiles. Although causality cannot be inferred, these patterns align with broader trends toward minimizing opioid use in emergency care.

Local anesthetics were administered to 18.7% of patients, often for laceration repairs or hematoma blocks. Among patients with fractures, 15.8% received local anesthetics. However, their broader use remains limited, largely due to the need for ultrasound-guided regional anesthesia training (USGRA), staff availability, and time constraints in the ED setting. Despite these barriers, regional anesthesia has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing opioid use and improving pain control in elderly patients [16–19]. Expanded training and multidisciplinary collaboration, particularly between emergency medicine and anesthesiology, could help integrate these techniques more broadly, especially in resource-limited environments.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. As a retrospective analysis, it relies on the accuracy and completeness of electronic medical record documentation. Unmeasured variables, including pain scores, trauma severity, and undocumented comorbidities, may have influenced both treatment and outcomes. The exclusion of patients with chronic pain or polytrauma limits the generalizability of findings to more complex cases. The single-center design also restricts external validity.

Importantly, the regression model examining the relationship between analgesic administration and ED length of stay did not adjust for confounding factors such as age, sex, comorbidity burden, or trauma type. This may have biased the observed associations and limits causal interpretation. Future studies should incorporate multivariable models to better elucidate the independent effects of analgesic strategies on ED outcomes.

Implications and future directions

Despite these limitations, this study provides a valuable foundation for improving geriatric pain management in low-resource EDs. Future research should use multicenter, prospective designs with standardized pain assessment tools and longer-term follow-up. Expanding the use of regional anesthesia techniques, especially in fracture management, may offer significant benefits and reduce reliance on opioids. Training emergency clinicians in USGRA and developing evidence-based pain protocols tailored to geriatric patients can enhance care quality across similar settings.

Conclusion

This study assessed pain management strategies for geriatric trauma patients in a tertiary ED in southern Puerto Rico. Our findings demonstrate the use of a multimodal, opioid-sparing approach emphasizing acetaminophen, NSAIDs, and limited use of local anesthetics. Given the growing global geriatric population and increasing concern over opioid-related complications, it is critical to advance pain protocols that prioritize safety, efficiency, and patient-centered care. Expanding access to regional anesthesia and fostering collaboration between specialties may further improve outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the emergency medicine and anesthesia teams at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital for their contributions to this study.

References

2. Cairns C, Ashman JJ, King JM. Emergency Department Visit Rates by Selected Characteristics: United States, 2021. NCHS Data Brief. 2023 Aug;(478):1–8.

3. Elder NM, Heavey SF, Tyler KR. Emergency Department Pain Management in the Older Adult. Clin Geriatr Med. 2023 Nov;39(4):619–34.

4. Tracy B, Morrison RS. Pain management in older adults. Clinical therapeutics. 2013 Nov 1;35(11):1659–68.

5. Platt E, Neidhardt JM, End B, Cundiff C, Fang W, Kum V, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Low-Dose Versus High-Dose Parenteral Ketorolac for Acute Pain Relief in Patients 65 Years and Older in the Emergency Department. Cureus. 2023 Jun 12;15(6):e40333.

6. Kim M, Mitchell SH, Gatewood M, Bennett KA, Sutton PR, Crawford CA, et al. Older adults and high-risk medication administration in the emergency department. Drug Healthc Patient Saf. 2017 Nov 8;9:105–12.

7. Fichtner A, Schrofner-Brunner B, Magath T, Mutze P, Koch T. Regional Anesthesia for Acute Pain Treatment in Pre-Hospital and In-Hospital Emergency Medicine. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2023 Dec 1;120(48):815–22.

8. Rajan J, Behrends M. Acute pain in older adults. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2019;37(3):507–20.

9. Cisewski DH, Motov SM. Essential pharmacologic options for acute pain management in the emergency setting. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018 Dec 10;19(1):1–11.

10. Chang HY, Daubresse M, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC. Prevalence and treatment of pain in EDs in the United States, 2000 to 2010. Am J Emerg Med. 2014 May;32(5):421–31.

11. American Society of Anesthesiologists. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):248–73.

12. Fama F, Murabito LM, Villari SA, Bramanti CC, Gioffrè Florio MA. Traumatic injury in elderly: outcomes in emergency care unit. BMC Geriatrics. 2010 May 19;10(Suppl 1):A106.

13. McGwin G Jr, May AK, Melton SM, Reiff DA, Rue LW 3rd. Recurrent trauma in elderly patients. Arch Surg. 2001 Feb;136(2):197–203.

14. Gioffrè-Florio M, Murabito LM, Visalli C, Pergolizzi FP, Famà F. Trauma in elderly patients: a study of prevalence, comorbidities and gender differences. G Chir. 2018 Jan-Feb;39(1):35–40.

15. Manly JJ, Jones RN, Langa KM, Ryan LH, Levine DA, McCammon R, et al. Estimating the Prevalence of Dementia and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the US: The 2016 Health and Retirement Study Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol Project. JAMA Neurol. 2022 Dec 1;79(12):1242–9.

16. Wolmarans M, Albrecht E. Regional anesthesia in the emergency department outside the operating theatre. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2023 Aug 1;36(4):447–51.

17. Shinde V, Penmetsa P, Dixit Y. Application of Nerve Blocks in Upper and Lower Extremity Trauma Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department of a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Prospective Observational Study. Cureus. 2024 Jul 29;16(7):e65664.

18. Ritcey B, Pageau P, Woo MY, Perry JJ. Regional Nerve Blocks For Hip and Femoral Neck Fractures in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. CJEM. 2016 Jan;18(1):37–47.

19. Abou-Setta AM, Beaupre LA, Rashiq S, Dryden DM, Hamm MP, Sadowski CA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of pain management interventions for hip fracture: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Aug 16;155(4):234–45.