Abstract

This 5-year retro-study determines the prevalence of thrombosis associated with PICC line insertion in infants hospitalized in NICU.

Background: Commonly placed central lines in neonatal intensive care units (NICU) include peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC), Umbilical venous lines (UVC) and Umbilical arterial lines (UAC). These central lines are accepted as the standard of care for nutrition and hemodynamic status monitoring. Neonates are known to be at risk for thromboembolism, particularly venous thromboembolism (VTE) related to central catheters. However, little is known about the true incidence of thrombosis and the requirement for therapy in this population

Methods: With Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, a retrospective review of PICC insertions performed at a Level IV Children's Hospital was conducted. The study period was from January 2016 to June 2020, during which, the patients who received lines were further investigated for thrombosis and phlebitis associated with PICC lines.

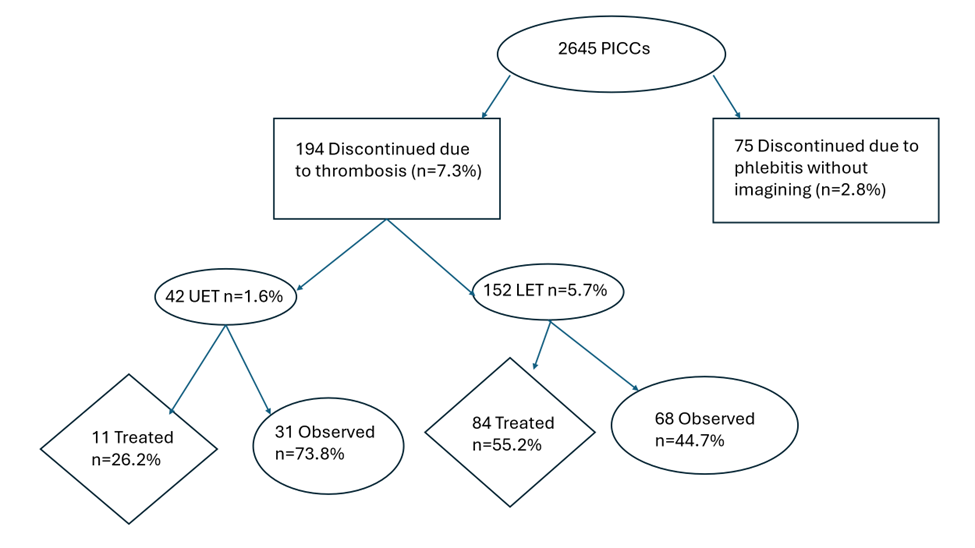

Results: 2645 PICCs were placed on 2337 neonates over 5 year period. There were 194 documented thrombosis (7.3%). 75 PICCs were removed due to a diagnosis of phlebitis without using an ultrasound (2.8%). Lower limb PICCs were associated with a higher incidence of thrombosis (5.7%) compared to upper extremity PICCs (1.7%). 26% of Upper Extremity Thrombosis (UET) required low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) treatment vs 55% of Lower Extremity Thrombosis (LET). During the same period that 75 neonates (2.8%) had PICC lines removed due to phlebitis in the pre-ultrasound period.

Conclusion: In the current study, neonates with a lower extremity PICC was associated with higher rate of PICC line thrombosis compared to UE PICC and required anticoagulation therapy more often.

Keywords

Thrombosis, Peripherally inserted central catheters, Anticoagulation, Neonates, Low molecular weight heparin

Abbreviations

PICC: Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter; UE: Upper Extremity; UET: Upper Extremity Thrombosis; LE: Lower Extremity; LET: Lower Extremity Thrombosis; DL: Double Lumen; SL: Single Lumen

Introduction

Neonatal PICC and umbilical lines are common vascular access lines in the NICU. Venous thrombosis, phlebitis, local or systemic infections, and mechanical problems such as catheter leakage or breakage, occlusions, and incidental dislodgement are well documented complications of PICC lines [1]. Neonatal thrombosis can result in serious morbidity or mortality due to irreversible tissue damage [2]. Based on the Canadian and International Registry of Neonatal admissions to the NICU, Schmidt & Andrew reported the incidence of thrombosis as 2.4 per 1000 admissions to the NICU, with 89% of thrombosis associated with intravascular catheters [2]. The reported incidence differs from unit to unit and ranges from 2.2% to 33.6%. [2-5]. Gender or age at birth has not been reported as a risk factor [4]. For infants with birth weight less than 1,000 grams the incidence of thrombus formation was 17.2% compared with 9.5% in infants of higher birth weight [6].

A more recent study suggested the incidence of PICC related thrombus was 0.23% (7/3043) [7]. In a study looking at upper extremity PICCs, 5% developed symptomatic venous thrombosis [8]. In routine ultrasound of all central lines, CVC-related thrombosis was found in 10.7% of asymptomatic neonates [6]. Asymptomatic upper extremity venous thrombosis associated with PICC line insertion can be as high as 23.3-38.5% [8,9].

Neonates are prone to thrombosis as they are more likely to have the Virchow’s triad: stasis of blood flow, injury to the endothelial lining, and hypercoagulability of blood components [10]. Neonates are inherently at high risk due to their immature vessels, small caliber of vessels, immature coagulation system, and clinical illness. In addition to that, low rate of infusion, hyperosmolar infusions, polycythemia, congenital heart disease, infection, asphyxia and the catheter material can also increase risk of thrombosis [6,11]. Thrombosis increases the risks of organ dysfunction, post-thrombotic syndrome, and neurodevelopmental sequelae [12]. Diagnosis of thrombosis also leads to multiple duplex studies, increased length of stay, anticoagulation treatment and level monitoring with multiple blood draws and hence results in increased healthcare expenditure.

Hence, it is important to quantify the incidence of thrombosis in this population along with treatment and duration of therapy.

Methodology

This study was conducted at an 88-bed, a level IV NICU with a large referral base. The study was approved by hospital IRB, and informed consent was waived. Data were aggregated retrospectively from a neonatal database over a 5-year period from January 2016 to December 2020.

At our institution, PICCs were placed by specialized neonatal nurses and were gradually changed to hospital line team by 2017. While the specialized NICU nurses used superficial veins to place PICC lines, the line team were more likely to use central veins under ultrasound guidance. By 2018, the vast majority of the PICC lines were placed by the hospital line team. As a general rule, PICCs were placed in lower limbs unless there is difficulty. The catheters consisted of both silicone and polyurethane material. Our double lumen PICC (1.9FR or 2.6 FR) are made of polyurethane material. The single lumen PICC (1.9FR) lines are made of either silicone or polyurethane.

Indications for placing PICC were determined by the attending neonatologists and included the need for prolonged parenteral nutrition, continuous infusion of vesicant medications, and prolonged antibiotic therapy. Heparin was routinely added at a concentration of 0.25 units per ml to 0.5 units per ml of the infusate. Informed consent was obtained before the insertion of a PICC. Care of PICCs was performed by our nursing staff with outcome monitoring documented on a procedural online logbook by the line team. Upper extremity PICCs were considered as central when the tips resided in the superior vena cava before the right atrium. For low extremity PICCs, the tips were ideally kept in high inferior vena cava at or above T10. Removal of PICCs was accomplished when there is complication, or feedings were advanced enough that supplemental fluids could be given by peripheral veins.

Statistics

Data analysis was performed using SAS 0.1. Non- parametric analysis X2 test was used. P<0.05 was considered significant.

|

No. of lumen |

Polyurethane catheters n=124 |

|

Silicone n=70 |

|

P value |

|

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

Double lumen |

29 |

(23) |

0 |

(0) |

<0.001 |

|

Single lumen |

95 |

(77) |

70 |

(100) |

|

P value less than 0.05 indicates that there is an association or difference between types of catheters and types of lumens.

Results

Catheter selection is based on an infant’s weight and size. Double lumen catheter is reserved for infants with multiple infusion needs. The choice of using upper extremity vs lower extremity simply depends on diagnoses, anatomy consideration, and risk factors for complication.

A total of 2,645 PICC lines were placed in 2,337 neonates during the five-year period. Some neonates had more than one PICC line placed. 194 neonates had PICC line associated thrombosis, and 75 neonates had their PICC line removed due to phlebitis in the time prior to routine imaging studies.

For the PICCs with documented thrombosis, the incidence was 7.3%. If all cases of phlebitis are associated with thrombus, then the incidence of PICC line-associated thrombosis would be 11.5%. Of the 42 upper extremity PICC line associated thrombosis, 11 were treated with LMWH (26.2%). Of the 152 lower limb PICC line associated thrombosis, 84 were treated with LMWH (55.2%). Before 2018, PICCs were removed due to phlebitis or limb swelling and ultrasound was not performed routinely.

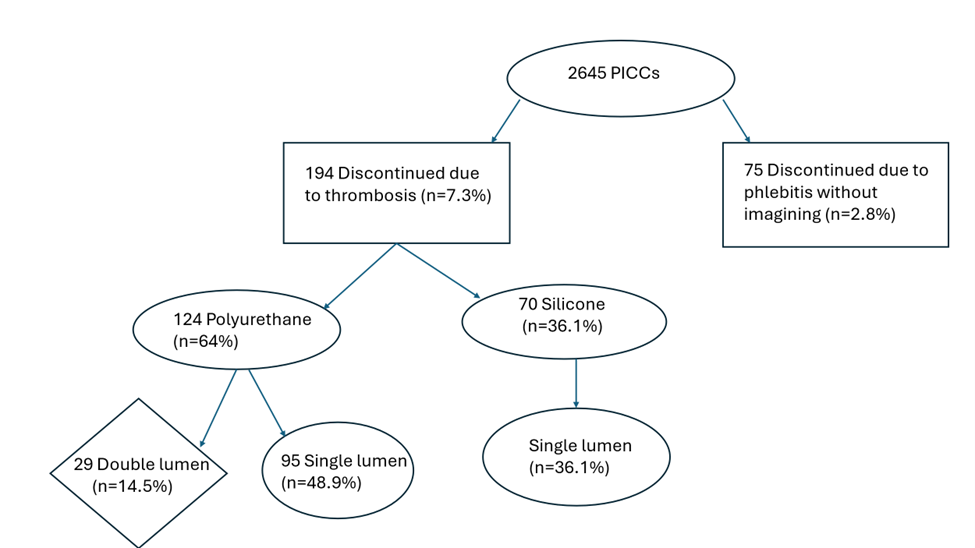

All the double lumen PICCs were made of polyurethane, and the single lumen were made of either silicone or polyurethane. Of the 194 patients with thrombosis, 124 (64%) had polyurethane catheters and 70 (36%) had silicone catheters. Of the 124 polyurethane catheter associated thrombosis, 29 (14.5%) had double lumen and 95 (48.9%) had single lumen PICCs. The 70 silicone PICC associated thrombi accounted for 36.1%.

Over a five-year period, 2645 PICCs were successfully placed on 2,337 neonates in this institution. Of the 2,337 neonates who had PICCs placed, 2,143 neonates did not have PICC lines removed due to thrombosis; and for 2,068 neonates their PICC lines were not discontinued due to either thrombosis or phlebitis.

Figure 1. PICC line catheters: lumen number and extremity placed.

Figure 2. PICC line thrombosis incidence and treatment. UET: Upper Extremity Thrombosis; LET: Lower Extremity Thrombosis.

Figure 3. PICC line material and lumen number.

Discussion

Our study results show that our documented PICC associated thrombosis incidence is at least 7.3%. If some of the phlebitis were associated with thrombosis, then the true incidence is likely to be somewhere between 7.3 to 10.1%. The incidence of thrombosis is higher in lower extremities than upper extremities as the majority of our PICC lines were placed in the lower extremities. Thrombosis occurred more with polyurethane catheters (64%) compared to silicone catheters (36%). This number might be biased due to our unit utilizing mostly polyurethane catheter during that period. Anticoagulation treatment usually ranges from 6-12 weeks depending on the size and evolution of the thrombus and involves laboratory monitoring of the anti Xa level.

Diagnosis of central catheter related thrombosis can be based on clinical findings including phlebitis, limb edema, altered perfusion or line occlusion [6]. In one study, doppler ultrasonography aided in the diagnosis in 68% of cases [2]. However, ultrasound remains the most practical tool despite its lower sensitivity [6]. Venography is considered the gold standard for diagnosing Central Venous Catheter (CVC)-related thrombosis [6]. Multiple studies indicate that most CVC-related thrombosis are silent, but some are associated with line dysfunction, limb swelling, altered skin color or perfusion, and /or thrombocytopenia [6]. The centers that perform routine ultrasounds report a higher incidence of thrombosis compared to the centers that perform ultrasounds only if symptoms occur. The incidence of thrombosis might be elevated due to the increased surveillance. Hence it is difficult to obtain the true incidence of thrombosis [4,7-9]. Symptoms of impaired liver function, hepatomegaly and splenomegaly may suggest thrombus location in the portal vein [4]. Superior vena cava syndrome, chylothorax, and chylopericardium may indicate thrombus in upper extremities [4]. Renal vein thrombosis can be present with hematuria, abdominal masses, and thrombocytopenia [2].

In the study by Chojnacka et al., the location of thrombosis was found to be in central veins such as the portal vein (25%), iliac vein (18.8%), the inferior vena cava (37.5%), the hepatic vein (12.5%), and the superior vena cava (6.3%) [4]. Kisa et al. reported that all patients with a major thrombotic complication had a lower extremity PICC which was at or below L1 (L1-S1) and had parenteral nutrition infusions and significant intra-abdominal pathology. It was suggested that intra-abdominal hypertension and compartment syndrome led to venous stasis, completing the thrombogenic triad [12].

Catheter materials used in PICCs are correlated with the occurrence of a variety of infections. Catheters made of silicone are associated with a higher risk of infection and microorganism colonization than polyurethane PICCs. Polyurethane PICCs provide greater wall strength and allow for high flow because of a larger inner lumen even with a small size catheter [1].

Coagulase-Negative staphylococcus was the predominant blood stream infection, 15 of 69 CVC with a thrombus (21.7%) [6]. Infection promotes clotting activation, and catheters provide a center for thrombus formation in a neonate with developmentally decreased inhibitors of coagulation [4]. Long-term PN and hyperosmolar solutions may result in increased endothelial damage occlusion by foreign materials and thrombosis [4].

Larger catheter size compared to the vein lumen and double lumen catheters are more prone to thrombosis [8,13,14]. Single-lumen PICCs with a smaller gauge are associated with lower complication rates (17.2/1000) compared with double lumen PICCs (30.8/1000) [14].

Vein measurement by ultrasound is recommended to optimize central venous catheterization and that matching vein diameter with catheter caliber can reduce venous thrombosis [3]. It is recommended that the external diameter of the catheter should not exceed one-third of the internal diameter of the vein [3]. The most important factor is the relationship between the outer diameter of the catheter and the inner diameter of a catheter [4]. One study recommended the appropriate catheter to be a single-lumen, high-volume with a small diameter made of polyurethane, based on low incidence of thrombosis in their unit [9].

Management of CVC with thrombosis includes observation for spontaneous resolution, removal of the central line, and anticoagulation [4,8]. Anticoagulation therapy can lead to partial or complete resolution of thrombosis in 59-100 % of cases [8]. The Desjardin et al. study stated that anticoagulation therapy tends to be more effective in achieving a partial (44% vs 18 %) and complete resolution (18% vs 10%) of thrombosis than conservative treatment. There were no differences between treatment groups regarding safety outcomes assessed by major bleeding, minor bleeding, or transfusion [14]. LMWH, enoxaparin is the anticoagulant of choice due to its predictability of the anticoagulant effect [15,16]. Anti-Xa assays are used to monitor the therapy. The Zhu et al. study concluded that the average course of LMWH was 10 days. However, other studies have quoted a longer duration of treatment up to 6 months or until collateral vessels have developed [16]. Thrombolytic therapy should be reserved for limb necrosis, organ failure, or life-threatening thrombosis [4].

The major limitation is this is a retrospective study performed over a five year period. During this five year period, there were various providers placing PICC lines in different locations, using superficial vs. deeper veins, ultrasound vs. blind procedure, hence, the true incidence will vary even within our institution. In addition, chart reviews were done in 2645 patients, and data collection was conducted using provider charting, hence there is an inherent variability and limitations when assessing for characteristics of PICC lines, thrombosis, treatment, and resolution.

Conclusions

This study examines thrombus cases over 5 years in a level IV NICU. It provides a deeper understanding of potential complications following application and insertion of PICCs in hospitalized infants, thereby helping to decrease the incidence of thrombosis. Through the appropriate choice and care of catheter, the rate of possible infectious, mechanical, and thrombotic complications could decrease. The secondary gain would be decreasing hospital stays and the need for intensive monitoring, thereby reducing health care expenditure.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflicts of interest amongst all authors.

Acknowledgements of Data Collection

Roces Velasco, Katie Jackson, Debra Suryn, Rina Steyn, Katherine Miller, Aurelia Rae Ayala, and Sandy Ross.

References

2. Schmidt B, Andrew M. Neonatal thrombosis: report of a prospective Canadian and international registry. Pediatrics. 1995 Nov 1;96(5):939-43.

3. Barone G, D'Andrea V, Vento G, Pittiruti M. A Systematic Ultrasound Evaluation of the Diameter of Deep Veins in the Newborn: Results and Implications for Clinical Practice. Neonatology. 2019;115(4):335-40.

4. Chojnacka K, Krasiński Z, Wróblewska-Seniuk K, Mazela J. Catheter-related venous thrombosis in NICU: A case-control retrospective study. J Vasc Access. 2022 Jan;23(1):88-93.

5. Milstone AM, Reich NG, Advani S, Yuan G, Bryant K, Coffin SE, et al. Catheter dwell time and CLABSIs in neonates with PICCs: a multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics. 2013 Dec;132(6):e1609-15.

6. Haddad H, Lee KS, Higgins A, McMillan D, Price V, El-Naggar W. Routine surveillance ultrasound for the management of central venous catheters in neonates. J Pediatr. 2014 Jan;164(1):118-22.

7. Zhu W, Zhang H, Xing Y. Clinical Characteristics of Venous Thrombosis Associated with Peripherally Inserted Central Venous Catheter in Premature Infants. Children (Basel). 2022 Jul 28;9(8):1126.

8. Sarmento Diniz ER, de Medeiros KS, Rosendo da Silva RA, Cobucci RN, Roncalli AG. Prevalence of complications associated with the use of a peripherally inserted central catheter in newborns: A systematic review protocol. PLoS One. 2021 Jul 23;16(7):e0255090.

9. Abdullah BJ, Mohammad N, Sangkar JV, Abd Aziz YF, Gan GG, Goh KY, et al. Incidence of upper limb venous thrombosis associated with peripherally inserted central catheters (PICC). Br J Radiol. 2005 Jul;78(931):596-600.

10. Monagle P, Newall F. Management of thrombosis in children and neonates: practical use of anticoagulants in children. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2018 Nov 30;2018(1):399-404.

11. Saxonhouse MA. Management of neonatal thrombosis. Clin Perinatol. 2012 Mar;39(1):191-208.

12. Desjardins MP, Hebert A, Pelland-Marcotte MC. 74 Central Line Related Thrombosis in Neonates: A Population -Based Study. Pediatrics and Child Health. 2021;26 (1):e55.

13. Kisa P, Ting J, Callejas A, Osiovich H, Butterworth SA. Major thrombotic complications with lower limb PICCs in surgical neonates. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 May;50(5):786-9.

14. Pedreira ML. Obstrução de cateteres centrais de inserção periférica em neonatos: a prevenção é a melhor intervenção [Obstruction of peripherally inserted central catheters in newborns: prevention is the best intervention]. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2015 Jul-Sep;33(3):255-7.

15. Roy M, Turner-Gomes S, Gill G, Way C, Mernagh J, Schmidt B. Accuracy of Doppler echocardiography for the diagnosis of thrombosis associated with umbilical venous catheters. J Pediatr. 2002 Jan;140(1):131-4.

16. Bohnhoff JC, DiSilvio SA, Aneja RK, Shenk JR, Domnina YA, Brozanski BS, et al. Treatment and follow-up of venous thrombosis in the neonatal intensive care unit: a retrospective study. J Perinatol. 2017 Mar;37(3):306-10.