Abstract

Yoghurt and cheeses are important rich food for the human, however they might be subjected to adulteration, which alter their quality. This study investigated the effect of milk adulteration on the processing properties of yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese and their chemical composition. Cheese and yoghurt were made from milk with known amounts of added water, penicillin, and ammonium chloride; separately. The obtained data showed that no fermentation occurred when the milk was diluted by the addition of 25% water, ammonium chloride and penicillin. The fermentation period and yield of yoghurt were significantly (P≤0.001) affected when adding water. The fermentation period was longer and the yoghurt yield was less in 15% diluted milk yoghurt compared to the control yoghurt. The values of the chemical composition of yoghurt were significantly decreased when diluted milk was used for making yoghurt. Similarly, the coagulation time and yield of the cheese were significantly (P≤0.001) affected by the diluted milk. However, the data showed non-significant (P>0.05) variation for the coagulation time, yield and compositional content of Sudanese white cheese made from milk containing 3 mL and 5 mL/ liter penicillin. The values of total solids, fat, protein, and salt in the cheese were significantly (P≤0.01) affected by the addition of water. The results revealed that the salt content of Sudanese white cheese were not significantly (P>0.05) affected by the addition of 15% and 25% water. The total solids, fat, protein, and salt contents of the cheese were affected by the addition of ammonium chloride to the milk, they revealed 45.5±0.94% vs. 43.63±0.86%, 22.86±1.46% vs. 21.94±2.46%, 15.31±1.82% vs. 14.86±0.93% and 5.36±1.86% vs. 5.79±0.36%, respectively in the milk with 3% vs. 5% added ammonium chloride. This study concluded that yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese processing, yield and chemical composition were affected by milk adulteration.

Keywords

Milk adulteration, Penicillin, Ammonium chloride, Yoghurt, Sudanese white cheese, Fermentation, Chemical composition

Introduction

Animal products including dairy products are rich in proteins that are known for their high nutritional values and hence they are vulnerable to many adulterations with cheaper products to maximize producers’ profits [1]. The practice of milk adulteration resulted in the reduction of milk quality and its contamination with hazardous substances will impact the health of the consumers [2]. Moreover, milk products such as yoghurt and cheese are among the most nutritious foods due to their contents of high-value protein. Thus, those high price products might be subjected to adulteration with low-quality products or with foreign substances [3].

Milk and its products are rich in nutrients and their consumption as the human diet is currently increasing [4]. Moreover, the consumption of dairy products is expected to grow and therefore, a faster precise way for the authentication of these products is required to save the public health [5]. Furthermore, authentication of milk products should involves accurate detection methods capable of confirming that the milk product matches the stated labels, which conform some laws and regulations [6]. The application of near-infrared spectroscopy and hyperspectral imaging for the detection of cheese and yogurt fraud are highlighted [5].

Milk adulteration is considered a multi-chain process because it starts from the farms by the animal owner, then by sales including milkmen and rural collection centers and ends with the processers in the processing units [7]. Milk fraud as a malpractice in developing countries is becoming an increasing problem due to the increased demand, growth in competition in the dairy market as well as the increase in the complexity of the milk supply chain and the lack of strict food safety laws [8]. Thus, the authenticity of dairy products has become an urgent issue for producers, researchers, governments and consumers. The outcome of the increase in falsification procedures will lead to loss of money and minimizing the consumers’ confidence [9].

High level of adulteration in the retail trade of sheep dairy products was detected and only 27.5% of the yoghurt samples and 20% of the cheese samples contained pure sheep milk. Moreover, the adulterant by cow’s and goat’s milk revealed 37.5% and 22.5% of the examined yoghurt and 35% and 17.5% of the tested cheese samples, respectively [10]. Yoghurt is traditionally produced by the bacterial fermentation of milk with a starter culture and its popularity is due to its reduced fat content, special texture and flavor, nutritional content and health benefits [11]. Although yoghurt and its related products are favored by many people, various adulteration in milk and yoghurt products showed great public concern about the quality and safety of yoghurt [12].

The addition of cheese whey to milk as a fraud was high and the economic effects are due to the low yield for dairy products and the reduced nutritional value of milk and its derived products as well as some safety issues [13]. Because cheese has a higher price compared to other dairy products, it is subjected to fraud worldwide [14].

Different types of health issues occur especially in children of 5-10 years of age due to adulterated milk and milk products, they might suffer from weak eyesight, diarrhea and stomach disorders, while, adults might suffer from cardiac attack and gastrointestinal problems. Moreover, adulteration is harmful to human health as it induces respiratory diseases such as gastro-intestinal problems and diarrhea [15]. The adulterants mostly found in raw milk sold in Khartoum State were the addition of water, the presence of salt and antibiotics especially during the late summer season [16]. This study was conducted with the objective of investigating the processing properties of yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese made from intentionally adulterated milk (water, ammonium chloride salt and penicillin). Also, the chemical composition of produced yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese were evaluated.

Material and Methods

Descriptions of yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese preparation

The milk used in this experiment was brought from the Animal Production Research Centre farm (Kuko) using clean bottles and transported to the laboratory of the Department of Dairy Production, University of Khartoum, where processing and examinations of produced yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese were done.

Nine trials were conducted to process both yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese from adulterated and controlled milk. Water (0%, 15%, and 25%), penicillin (0 mL, 3 mL, and 5 mL) and ammonium chloride salt (0%, 3%, and 5%) were added to a specific amount of milk (6 liters for cheese and 1 liter for yoghurt). Then each milk samples were processed into yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese to evaluate the effect of adulterants on the processing properties of yoghurt and cheese including time of coagulation and/or fermentation and yield for both products.

Adulterated milk and yoghurt processing

Milk was first divided into nine groups (1 liter for each group), according to the amounts of added ammonium chloride (0%, 3%, and 5%), added penicillin (0 mL, 3 mL, and 5 mL) and added water (0%, 15%, and 25%) to prepare the yoghurt samples.

According to Tamime and Robenson [17], one liter of milk (for each trail) was pasteurized (95°C for 15 seconds) and 20 mL of starter culture (Streptococcus thermophiles and Lactobacillus bulgaricus) produced by Chris Hansen (Denmark) were added directly to the milk followed by agitating to ensure homogenous distribution. After raising the temperature of the mix to 42–44°C, then the mixture was packed into plastic cups (100 grams). The filled cups were incubated at 42–44°C for 4–6 hours. The cups were removed from the incubator and stored in a refrigerator (8°C).

Adulterated milk and cheese processing

Milk was divided into nine groups (6 liters for each group) according to added ammonium chloride (0%, 3%, and 15%), added penicillin (0, 2 mL, and 5 mL) and added water (0%, 5%, and 15%) to prepare the Sudanese white cheese. The milk was strained by a clean cloth, heated to 62°C for 30 minutes and cooled to 40°C. The animal rennet (Chris Hansen- Denmark) was added (1.3 g/50 L milk) and the mixture was left to develop a curd. After complete coagulation, the curd was cut into small cubes for whey separation, and then the curd of each cheese was poured into wooden jars (30×30×30 cm) lined with a clean cloth and left for 12 hours [18]. The whey of each produced cheese was collected separately into a clean container, cooled and used for preservation of the particular cheese.

Analytical methods for yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese

Assessment of processing properties of yoghurt and cheese

The average fermentation time of yoghurt and coagulation time of cheese were estimated per hours. Also, the cheese yield was calculated as the weight of the cheese obtained and expressed as Kg.

Chemical analysis

The obtained yoghurt samples were chemically analyzed for total solids, fat, protein, ash, and acidity. Meanwhile, the Sudanese white cheese samples were chemically analyzed for total solids, fat, protein, ash, acidity, and salt.

The total solids content of all produced yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese samples was determined according to the method of AOAC [19]. The fat content was determined by the Gerber method and the protein content was determined by the Kjeldahal method [19]. Also, the ash and titratable acidity of yoghurt were determined according to the standard method of AOAC [19]. Meanwhile, the salt content of cheese was determined according to the method described previously [20].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS program version 16 [21]. General Linear Models were used to determine the fermentation time, yield and the chemical composition of yoghurt and cheese that were made using intentionally adulterated milk. Means were separated using the least significant difference at P≤0.05. Graphs were plotted using Microsoft Excel sheet.

Results and Discussion

Effect of adulteration on fermentation period and yield of yoghurt

The fermentation period of yoghurt samples revealed significant (P≤0.01) variations in the milk with the different levels of added water (Table 1). As it was longer in yoghurt samples made using milk containing 15% added water (2.46±0.01% hours) compared to the control samples (2.30±0.16% hours). Meanwhile, no fermentation occurred when the milk was diluted with 25% water (Table 1). Moreover, the addition of up to 15% water to milk on plain yoghurt quality during refrigerated storage was detected [22]. The starter culture kinetics were affected in addition to the change of color and texture [22]. This is the expected results as the diluted milk is expected to produce watery yoghurt. However, the average yield of yoghurt samples was significantly (P≤0.001) higher (0.92±0.01 Kg) in the control yoghurt samples (Table 1). Variations of incubation and fermentation period for yoghurt made using the milk of sheep (3–4), goats (3–4) and camel (16–18) was demonstrated. As, firm, slightly firm and watery consistency was observed for yoghurt, respectively [23].

|

Levels of added water (%) |

Fermentation time (hours) |

Yield (Kg) |

|

0 |

2.30b±0.16 |

0.92a±0.01 |

|

15 |

2.46a±0.01 |

0.76b±0.03 |

|

25 |

No fermentation |

|

|

Significant level |

** |

*** |

|

Means in each row bearing the same superscript a, b, c, .. letters are not significantly different (P>0.05) **= (P≤0.01) *** = (P≤0.001) |

||

This study also demonstrated that no fermentation was obtained when ammonium chloride and penicillin were added to the milk before yoghurt processing. This study supported the fact that antibiotic residues in foodstuffs products that are processed by microbial fermentation, such as fermented milk products can interfere with the fermentation process by inhibiting the starter cultures, leading to manufacturing accidents and poor-quality foods [24]. Moreover, antibiotic residues showed a negative influence on the processing properties of cultured dairy products (mainly yoghurt and cheese) by inhibiting starter cultures, causing allergy and sensitivity in people and increasing the risk of antibiotic resistant organisms and thus economic impact [25]. On the other hand, the lactic acid production was reduced with the increase of stabilizers concentration, while showing an increasing trend with fermentation time [26]. Moreover, enzyme addition, together with starter culture addition were found to increase yoghurt viscosity and yield stress [27]. However, the yield and the amount of free whey released were significantly (P<0.05) affected by the addition of thickening agents; the yield ranged from 29.71±6.59% to 80.98±6.08%, with an overall average of 55.38±5.33% [28].

Effect of added water on chemical composition of yoghurt

The compositional contents were affected when yoghurt was made from milk adulterated with water (Table 2). Moreover, no fermentation was obtained in milk samples with 25% added water (Table 2). The total solids contents were significantly affected by adding water to the milk (Table 2). A lower value was found in yoghurt samples made from 15% diluted milk (12.75±0.06%) compared to the control yoghurt (14.65±0.01%). Similarly, A lower mean level of total solids was found in the set yoghurt made from whole milk powder mixed with skim milk powder samples (14.00±0.87%) than those made using whole milk powder (15.29±0.524%) [29]. Moreover, high solids content in branded yoghurt samples was reported compared with those of unbranded samples [30]. The reason was attributed to the presence of a high quantity of stabilizer present in the branded samples and non-standardized or adulterated milk was used for unbranded yoghurt preparation [30]. Similarly, the difference in the total solids content may be due to the difference in fat, protein, ash, and sugar content of yoghurt samples [31]. Moreover, the level of added material, milk total solids content, and the level of reduction of milk volume during boiling and storage duration play the key role in determining the total solids content of Dahi yoghurt [32]. Thus, the addition of water to the milk leads to the reduction in its nutritional value including the protein and fat contents [16,33,34]. On the other hand, milk from different animal species also was found to affect yoghurt properties [23,35]. When yoghurt is made from pure sheep milk or a mixture of sheep and camel milk shorter coagulation time was obtained in comparison to those made from pure camel milk, which is due to the more liquidity status of camel milk [35].

|

Chemical composition (%) |

Levels of added water (%) |

Significant level |

||

|

0 |

15 |

25 |

||

|

Total solids |

14.65b±0.01 |

12.75a±0.06 |

|

* |

|

Fat |

5.14a±1.20 |

2.20b±1.01 |

No fermentation |

*** |

|

Protein |

4.25a±0.83 |

2.75b±0.33 |

*** |

|

|

Ash |

0.83a±0.18 |

0.65b±0.13 |

*** |

|

|

Titratable acidity |

0.79a±0.35 |

0.71b±0.06 |

* |

|

|

Means in each row bearing the same superscript a, b, c, .. letters are not significantly different (P>0.05) *= P≤0.05 *** = P≤0.001 |

||||

The fat content (Table 2) showed a highly significant difference in the yoghurt made using milk with 15% added water (2.20±1.01%) compared with the control one (5.14±1.20%). It was low in yoghurt made using diluted milk. The reason behind the lower level of fat content found in this study might be due to the preparation of yoghurt from diluted milk. The examination of 10 locally produced and 6 commercial brands of sweetened yoghurt samples in Bangladesh revealed that both branded and unbranded sweetened yoghurt samples had fat contents that ranging between 1.56±0.09 and 2.63±0.2%, which were low compared to the standard level (3%) [36]. This result was in line with the previous report, which stated that the variation in fat content between different Indian Dahi (yoghurt) samples might be due to the lack of quality control or adulteration of milk [31]. Similarly, significant variation (P≤0.001) was found between the yoghurt samples that were produced by the different manufacturers in Khartoum State in their chemical composition, as 73 of the examined yoghurt samples (50.7%) were found to have a lower fat content than the standard [37]. Yoghurt that with low fat showed whey separation, taste alterations and a reduction in acceptability by the consumer [38].

The average protein content of yoghurt samples was significantly (P≤0.001) higher (4.25±0.83%) in the control yoghurt samples compared to the yoghurt made from milk with 15% added water (2.75±0.33%) as shown in Table 2. The protein content of yoghurt made from full cream milk, skimmed milk, cow milk, and tiger-nut milk ranging from 4.78 to 5.23%, skimmed milk yoghurt had the highest crude protein content (5.23%), while full cream yoghurt had the lowest (4.78%) [39]. Similarly, the protein content (3.71±0.02-4.33±0.15%) was high in the local and commercial brands of sweetened yoghurt samples compared to the standard level of 3.2% in Bangladesh [36]. Yoghurt was found to be adulterated using non-milk proteins, including vegetable protein powder, edible or industrial gelatin, and soy protein powder have been frequently used for yoghurt adulteration [11]. This study supported the previous one, which stated that the potential risk of unknown adulterated yoghurt for consumers necessitates stringent regulatory measures to reduce such malpractices [22].

The ash content of yoghurt was significantly affected by the water addition to the milk as higher value was found in control yoghurt samples (0.83±0.18%) as shown in Table 2. Similarity, a lower mean level for the ash (0.769±0.10 vs. 0.770±0.081%) was reported in the set yoghurt made from whole milk powder mixed with skim milk powder compared to the samples made using whole milk powder [29]. Similarly, the ash content of yoghurt taken from shops was higher than that of the household [40]. Moreover, a significant difference (P<0.05) in the ash content among different homemade and small-scale dairy plants buffalo yoghurt was reported [41]. The highest ash content was found in home-made (0.94%) and the lowest ash percent was found in small-scale dairy plants (0.90%).

The acidity of yoghurt was significantly affected by adding water to the milk from which yoghurt was made (Table 2). It was higher in the control yoghurt (0.79±0.35%). The acidity of reconstituted mixed milk (whole and skim milk powder) set yoghurt was higher (0.847±0.127%) compared to reconstituted whole milk set yoghurt (0.770±0.081%). Moreover, the increase in titratable acidity might be because of the high total solids and fat content of whole milk set yoghurt that influences the lactic acid bacteria activity [29]. The data obtained in this result is also in line with those obtained for the acidity of local unbranded sweetened yoghurt (0.66±0.05- 0.72±0.05%), while it was low compared to those obtained for commercial branded sweetened yoghurt (0.71±0.05-0.77±0.05%) [36]. The difference in acidity content of different yoghurt samples might be due to the use of variable quantities of bacterial culture, processing conditions, and preservation method [31]. The widespread practice of adulterating milk using water in developing countries has a significant negative economic on milk products like yoghurt [22].

Upon the addition of ammonium chloride or penicillin during this study to the milk before yoghurt processing, no fermentation was observed. However, ammonium sulphate was reported in the sweetened yoghurt samples examined in Bangladesh [36]. The selection of penicillin in this is mainly because of its commonly used for the treatment of animal disease [42]. Penicillin; which is also commonly used in most farms in Sudan; revealed the highest resistance towards the isolated bacteria [43].

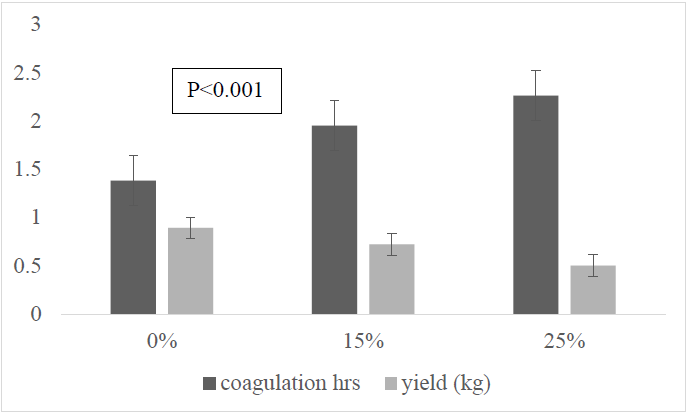

Effect of added water, ammonium chloride, and penicillin on coagulation period and yield of Sudanese white cheese

The average cheese coagulation time (2.26±0.01 hours) was significantly (P≤0.001) higher in the cheese samples made from the milk containing 25% added water. However, the average yield of the cheese samples (0.89±1.34 Kg) was significantly (P≤0.001) higher in the cheese samples made from the control milk (Figure 1). Previously, a relationship was shown between the increase of cheese yields and the reduction of the coagulation time [44]. Therefore, this is leading to economic loss as the higher the recovered percentage of solids, the greater is the amount of the obtained cheese. This result is similar to that which indicated the importance of highlighting the role of both the coagulation and cheese yield traits as they normally influenced by milk composition especially fat and protein content [45]. The variations obtained in the content of Sudanese white cheese are mainly because of differences in milk composition and manufacturing methods [46]. More time is reported for coagulating camel milk into cheese [44,47,48], which might be due to the large size of casein micelles [49]. In addition, the yield of fresh cheese was significantly correlated to the fat and protein contents, this variable alone explained 77% of fresh yield variability [50]. However, it was reported that cheeses are a very diverse category of dairy products, the composition and structure of which can vary greatly depending on the type, milk pre-treatment and manufacture process, and maturation regime [51].

Figure 1. Effect of added water on coagulation and yield of Sudanese white cheese.

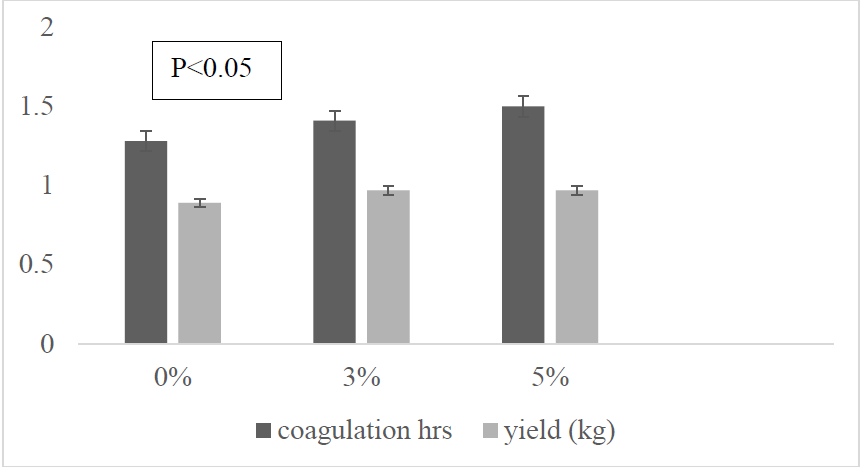

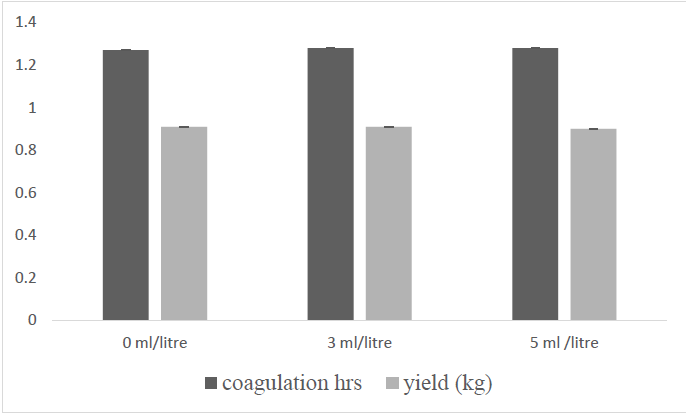

The average coagulation period for the cheese made from the milk with added ammonium chloride was significantly (P≤0.001) higher (1.50±0.33 hours) in the cheese samples made from milk with 5% added ammonium chloride (Figure 2). However, the average yield obtained for the cheese was significantly (P≤0.05) higher in the samples made using the control milk (Figure 2). However, the yield and coagulation time of cheese were not significantly (P>0.05) affected by the addition of the levels of penicillin used, the average coagulation time was low (1.27±0.01 hours) in the cheese samples made from the control milk. The average yield was lower (0.90±0.63 kg) in the cheese samples from the milk containing 5 mL of penicillin/6 liter of milk (Figure 3). However, it was reported that antibiotic residues in cheese can interfere with the fermentation process by inhibiting the starter cultures and thus poor-quality products [24].

Figure 2. Effect of added ammonium chloride on coagulation and yield of Sudanese white cheese.

Figure 3. Effect of added penicillin on coagulation and yield of Sudanese white cheese.

Effect of added water on the chemical composition of cheese

The means of total solids, fat, protein, and salt content were significantly (P≤0.001) higher in the cheese samples made from free-added water milk. They revealed 45.7±1.79%, 16.67±1.42%, 20.30±1.87%, and 3.75±0.85%, respectively (Table 3).

|

Chemical composition (%) |

Added water (%) |

Significant level |

||

|

0 |

15 |

25 |

||

|

Total solids |

45.71a±1.79 |

38.12b±1.85 |

29.11c±1.96 |

*** |

|

Fat |

16.67c±1.42 |

10.23b±1.33 |

8.10a±1.23 |

*** |

|

Protein |

20.30a±1.87 |

16.23b±2.13 |

11.36c±1.83 |

*** |

|

Salt |

3.75a±0.62 |

3.32b±0.85 |

3.12c±0.37 |

*** |

|

Means in each row bearing the same superscript a, b, c, .. letters are not significantly different (P>0.05) N.S: Non significant (P>0.05) *** = P≤0.001 |

||||

The addition of water to cheese milk also affects the total solids content of cheese (Table 3). Compared to the results shown in Table 3, higher total solids content was reported for the Sudanese white cheese in the markets of Khartoum North (47.8%) [52], in South and West Darfur states (52.84%) [53] and in New Halfa, eastern Sudan (50.88±5.57%) [54]. Meanwhile, the total solids revealed 48.14% and 45.76% for traditionally produced Sudanese white cheese samples and those produced by the modern industry, respectively [46]. The factors that affect the quality of the Sudanese white cheese and its nutritional value include the compositional content of the food materials used and their nature, the preservative and the packing used [55].

Total solids parentage decreased as the added water increased (Table 3). The total solids losses in whey were significantly affected (P<0.01) by the fat and protein contents, and initial pH of the milk [56]. Higher total solids, fat, and ash content were found in the whey of camel cheese, which is indicative of the watery content of camel milk [44].

Fat content was decreased as the added water increased (Table 3). Similar protein levels were reported previously [53,54], meanwhile, lower values for the Sudanese white soft cheese were reported [52]. However, high fat content was reported for both the Sudanese white cheese samples obtained from traditional producers (21.10%) and those produced by modern industry (22.35%) in Khartoum State [46]. Moreover, the different fat percentages of milk showed significant differences (P<0.05) in the fat content of cheese [57]. Also, the fat content of 4 studied types of cheeses revealed significant differences, which is due to the decrease in the moisture content [58]. In addition, it was found that as the fat content of milk decreased, the moisture, protein, and calcium contents of the cheese increased significantly because moisture did not replace the fat on an equal basis [59]. Cheese had the highest adulteration rate among dairy products and the replacement of ingredients and reduced fat are some of the important factors in its adulteration [60]. Also, in cheese, the most common frauds that were reported include using milk from other species, mixing milk and the addition of vegetable oils or soybean oil [14].

Cheese protein content was significantly affected by the addition of water (Table 3). Variations were reported in the protein content of the Sudanese white cheese. A lower protein content was obtained in Sudanese white cheese samples (15.9%) collected from the supermarkets of Khartoum North [52]. Also, lower protein content was found in the Sudanese white cheese samples examined from the traditional producers (13.07%) and those produced by the modern industry (15.36%) in Khartoum State [46]. However, higher values were reported in South and West Darfur states (23.79%) [53] and New Halfa, eastern Sudan (23.38±4.80%) [54]. On the other hand, a part of soya proteins and soya milk is also added to bovine milk either for sale as fluid milk or in the preparation of cheese for revenue maximization [61]. This might be because cheese yield is strongly influenced by the composition of milk, especially fat and protein contents, and by the efficiency of the recovery of each milk component in the curd [45].

Effect of added ammonium chloride on the chemical composition of cheese

Table 4 showed that the means of total solids, fat, protein and salt content were significantly (P≤0.01) affected by milk adulteration with ammonium chloride.

|

Chemical composition (%) |

Added ammonium chloride (%) |

Significant level |

||

|

0 |

3 |

5 |

||

|

Total solids |

47.71a±1.79 |

45.5b±0.94 |

43.63c±0.86 |

** |

|

Fat |

20.36a±1.83 |

22.86b±1.46 |

21.94b±2.46 |

** |

|

Protein |

17.82a±0.94 |

15.31b±1.82 |

14.86b±0.93 |

** |

|

Salt |

3.50a±0.86 |

5.36b±1.86 |

5.79c±0.36 |

** |

|

Means in each row bearing the same superscript a, b, c, .. letters are not significantly different (P>0.05) *= P≤0.05 **= P≤0.001 |

||||

The total solids content of the Sudanese white cheese was significantly affected by the addition of ammonium chloride (Table 4) and was significantly (P≤0.01) high in the control cheese samples (47.71±1.79%). Cheese was reported to be adulterated with salt [60]. The total solids content of the control cheese was substantially higher (P<0.01) than the others [62]. In comparison to the control, the addition of Moringa, Bidara and Bay leaves herbal extracts and their combination resulted in the reduction of the total solids content of cheese [62]. Moreover, the total solids and protein contents of milk were the most significant predictors of Chevre cheese yield [63].

The average fat content was higher (22.86±1.46%) in the cheese samples from milk containing 3% added ammonium chloride. Meanwhile, the average protein content was higher (17.82±0.94%) in cheese samples made from milk free from ammonium chloride (Table 4). Similarly, using milk with different fat content for the production of Sudanese white cheese was significantly (P<0.05) influenced the level of salt content of the cheese [55]. Moreover, salt levels of the cheese are considered the major factor that contributed to the variation of ash content in the cheese [54,64–66]. Salt level in cheese has a major effect on lipolysis, proteolysis and para-casein hydration during ripening [67]. Moreover, the changes in protein content of the cheese made by adding different salt percentages to milk may be attributed to the proteolytic activity during storage [68].

Salt content of Sudanese white cheese was significantly affected by the addition of ammonium chloride to the milk (Table 4). The cheese made from milk adulterated with the addition of 5% ammonium chloride revealed the highest average salt content (5.79±0.36%) as shown in Table 4. However, the average salt in traditionally produced Sudanese white cheese samples was reported as 7.57±2.28% and a range of 5.0 to 15.0%, while that obtained from the modern industry revealed a mean of 4.06±1.29% and a range of 3.0 to 7.0% [46]. This result was similar to those reported on the effect of partial substitution of NaCl with KCl on the chemical composition of Halloumi cheese, as a significant difference was found in ash, sodium, and potassium contents among experimental cheeses at the same storage period [69]. Moreover, the ash, sodium, and potassium contents increased significantly during the storage using some salt treatment [69]. Also, replacing NaCl with KCl resulted in a significant reduction of the moisture content of the cheeses up to 17 days of ripening [70]. Furthermore, Sheibani et al. found that the chemical compositions of experimental cheeses using different salt levels at day 0 (right after pressing) revealed significant (P<0.05) reduction in salt that was affected by both the moisture and salt-in-moisture contents of the experimental cheeses [71]. This goes in line with Sudanese standards that the average fat content of Sudanese white soft cheese should not exceed 20% and the ash to be 5% as the lowest value [72].

Effect of added penicillin on the chemical compositions of cheese

In the present study, the total solids, fat, protein and salt content of Sudanese white cheese were not significantly (P>0.05) affected by adding the 3 levels of penicillin to the milk (Table 5). The averages total solids content of cheese samples made from the milk without the addition of penicillin (control) and the addition of 5 mL/6 liters were lower (56.95±0.86%) than the average total solids content of cheese samples made from milk with 3 mL/6 liter added penicillin (Table 5). The mean of fat content revealed 24.95±1.94% for Sudanese white cheese made from milk free from penicillin compared to that made using milk containing 3 mL/6 liter of penicillin (24.95±0.86%). The average protein content was higher (26.41±1.83%) in the cheese samples made from milk containing 3 mL/6 liters and 5 mL/6 liters of penicillin. However, the mean salt content of Sudanese white cheese was higher (3.40±0.72%) in the cheese made from control milk with no addition of penicillin (Table 5).

|

Chemical composition (%) |

Added penicillin (mL/6 liter) |

Significant level |

||

|

0 |

3 |

5 |

||

|

Total solids |

56.95±0.82 |

56.96±0.98 |

56.95±0.86 |

NS |

|

Fat |

24.95±1.94 |

24.91±0.86 |

24.95±1.03 |

NS |

|

Protein |

26.40±2.64 |

26.41±1.91 |

26.41±1.83 |

NS |

|

Salt |

3.40±0.72 |

3.39±0.83 |

3.39±0.36 |

NS |

|

NS: Non significant (P>0.05) |

||||

Antibiotic residues affect cheese-making process by inhibiting the growth of the starter cultures, acidification, milk curdling as well as ripening [73]. Fortunately, penicillin G residue was not detected in cheese, while it was found in the whey at concentrations similar to those added to raw milk [74]. Similarly, the cheese-making process was unaffected by the presence of most antibiotics evaluated, as only erythromycin and oxytetracycline were significantly prolonging the time required for cheese production (122±29 and 108±25 minutes, respectively) [73]. Although the antimicrobial drugs can also interfere with the manufacture of dairy products, decrease acid and flavor production associated with butter manufacture, reduce the curdling of milk, and cause improper ripening of cheeses [75]. Moreover, the occurrence of antibiotic residues might affect the quality and safety of raw milk and its products [76]. Also, safe milk must not contain any antibiotic residues and their occurrence in the milk of dairy farms, which is an indication of the misuse of antibiotics [77]. Moreover, generally, for the production of cheese, various kinds of milk or other additives have been used [78,79]. This has economic concern in the food industry as food fraud is considered a major problem [80,81]. The regulatory agencies spend a lot of money to assess and reduce food fraud because it has a fundamental connection to nutrition and public health [82,83]. In addition, the loss of confidence by investors, customers, consumers and authorities caused by food fraud and adulteration events can be far more damaging than the direct economic impact [84].

Conclusion

Based on these result, yoghurt and Sudanese white cheese quality, yield and chemical composition were significantly affected by the milk adulteration. The contents of total solids, fat, protein, ash, and titratable acidity in yoghurt were decreased by increasing the levels of the added water to the milk. Also, the cheese yield was significantly affected by the added water to the milk. The chemical composition of cheese showed significant variation due to the addition of ammonium chloride to the milk. The present study recommends that more efforts are needed to minimize the malpractice of adulteration of milk and to establish its standardization to produce high-quality milk and dairy products.

References

2. Poonia A, Jha A, Sharma R, Singh HB, Rai AK, Sharma N. Detection of adulteration in milk: A review. International journal of dairy technology. 2017 Feb;70(1):23–42.

3. Windarsih A, Rohman A, Irnawati, Riyanto S. The combination of vibrational spectroscopy and chemometrics for analysis of milk products adulteration. International Journal of Food Science. 2021;2021(1):8853358.

4. Lambrini K, Aikateri MF, Konstantinos K, Christos I, Papathanasiou V, Areti T. Milk nutritional composition and its role in a human health. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology. 2021;9:10–5.

5. Tavares HPG, Mederios SLM, Barbin FD. Near infra-red techniques for fraud detection in dairy products: A review. Journal of Food Science. 2022;87:1943–60.

6. Abbas O, Zadravec M, Baeten V, Mikuš T, Lešić T, Vulić A, et al. Analytical methods used for the authentication of food of animal origin. Food Chem. 2018 Apr 25;246:6–17.

7. Swar SO, Abbas RZ, Asrar R, Yousuf S, Mehmood A, Shehzad B, et al. Milk adulteration and emerging health issues in humans and animals (a review). Cont Vet J. 2021;1:1–8.

8. Handford CE, Campbell K, Elliott CT. Impacts of Milk Fraud on Food Safety and Nutrition with Special Emphasis on Developing Countries. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2016 Jan;15(1):130–42

9. Kamal M, Karoui R. Analytical methods coupled with chemometric tools for determining the authenticity and detecting the adulteration of dairy products: A review. Trends in Food Science & Technology. 2015 Nov 1;46(1):27-48.

10. Zarei M, Maktabi S, Yousefvand A, Tajbakhsh S. Fraud identification of undeclared milk species in composition of sheep yogurt and cheese using multiplex PCR assay. Journal of food quality and hazards control. 2016 Mar 10;3(1):15–9.

11. Xu L, Yan SM, Cai CB, Wang ZJ, Yu XP. The Feasibility of Using Near‐Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics for Untargeted Detection of Protein Adulteration in Yogurt: Removing Unwanted Variations in Pure Yogurt. Journal of analytical methods in chemistry. 2013;2013(1):201873.

12. Chan ZCY, Lai WF. Revisiting the melamine contamination event in China: implications for ethics in food technology. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2009 Aug;20(8):366–73.

13. Lima JS, Ribeiro DCSZ, Neto HA, Campos SVA, Leite MO, Fortini MER, et al. A machine learning proposal method to detect milk tainted with cheese whey. J Dairy Sci. 2022 Nov;105(12):9496–508

14. Abedini A, Salimi M, Mazaheri Y, Sadighara P, Alizadeh Sani M, Assadpour E, et al. Assessment of cheese frauds, and relevant detection methods: A systematic review. Food Chem X. 2023 Aug 6;19:100825.

15. Raturi N, Aman J, Sharma C. Study of adulteration in milk and milk products and their adverse health effects. Octa Journal of Biosciences. 2022 Jun 1;10(1):37–50.

16. Tayseer AS, El-Zubeir IEM. Chemical Preservatives, Adulterants, and Antibiotic Residues in Raw Cow's Milk in Khartoum State, Sudan. Veterinary Medicine & Public Health Journal. 2024 Sep 1;5(3):203–15.

17. Tamime AY, Robinson RK. Yoghurt Science and Technology, 2 nd edition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press LLC; 1999.

18. Osman AO. The Technology of Sudanese White cheese (Gibna Byuda). Dairy Development in Eastern Africa. Proc. IDF Seminar. 1987.

19. AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis. Association of Official Analytical Chemist, Benjamin Franklin Station, Washington, DC, USA. 2009.

20. Breene WM, Price WV. Dichlorofluorescein and Potassium Chromate as Indicators in a Titration Test for Salt in Cheese. Journal of Dairy Science. 1961 Apr 1;44(4):722–5.

21. SPSS. Social Package for Statistical System for Windows version 16. SPSS, Inc, Chicago. 2008.

22. dos Santos Rosario IL, Vieira CP, Salgado MJ, Monteiro NB, Alzate KG, de Araújo GC, et al. Assessment of plain yoghurt quality parameters affected by milk adulteration: Implications for culture kinetics, physicochemical properties, and sensory perception. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 2024 Aug;77(3):827–42.

23. El Zubeir IE, Basher MA, Alameen MH, Mohammed MA, Shuiep ES. The processing properties, chemical characteristics and acceptability of yoghurt made from non bovine milks. Development. 2012 Mar 22;24(3):50.

24. Arsène MM, Davares AK, Viktorovna PI, Andreevna SL, Sarra S, Khelifi I, Sergueïevna DM. The public health issue of antibiotic residues in food and feed: Causes, consequences, and potential solutions. Veterinary world. 2022 Mar 23;15(3):662–71.

25. El Zubeir IEM. Significant, risks and control of antibiotic residues in animal’s products with special reference to milk. UNESCO Chair of Bioethics Workshop: Building a more Equitable and Ethical Food and Agricultural System. Main Hall, Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, Sudan. 24-25 May 2017, Khartoum, Sudan.

26. Eze CM, Aremu KO, Alamu EO, Okonkwo TM. Impact of type and level of stabilizers and fermentation period on the nutritional, microbiological, and sensory properties of short-set Yoghurt. Food Sci Nutr. 2021 Aug 4;9(10):5477–92.

27. Pakseresht S, Mazaheri Tehrani M, Razavi SMA. Optimization of low-fat set-type yoghurt: effect of altered whey protein to casein ratio, fat content and microbial transglutaminase on rheological and sensorial properties. J Food Sci Technol. 2017 Jul;54(8):2351–60.

28. Sumarmono J, Setyawardani T, Rahardjo AH. Yield and Processing Properties of Concentrated Yogurt Manufactured from Cow’s Milk: Effects of Enzyme and Thickening Agents. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2019 Nov 1 (Vol. 372, No. 1, p. 012064). IOP Publishing.

29. Attita Allah AH, El Zubeir IEM & El Owni OAO. Some technological and compositional aspects of set yoghurt from reconstituted whole and mixed milk powder. Research Journal of Agriculture and Biological Sciences. 2010;6(6): 829–33.

30. Ahmad I, Gulzar M, Shahzad F, Yaqub M, Zhoor T. Quality assessment of yoghurt produced at large (industrial) and small scale. The Journal of Animal and Plant Sciences. 2013 Jan 1;23(1 Suppl):58–61.

31. Dey S, Iqbal A, Ara A, Rashid MH. Evaluation of the quality of Dahi available in Sylhet Metropolitan City. Journal of the Bangladesh Agricultural University. 2011;9(1):79–84.

32. Shekh AL, Wadud A, Islam MA, Rahman SM, Sarkar MM, Ding T, et al. Study on the quality of market dahi compared to laboratory made dahi. Journal of Food Hygiene and Safety. 2009;24(4):318–23.

33. Botelho BG, Reis N, Oliveira LS, Sena MM. Development and analytical validation of a screening method for simultaneous detection of five adulterants in raw milk using mid-infrared spectroscopy and PLS-DA. Food chemistry. 2015 Aug 15;181:31–7.

34. Mohammed AAA, El Zubier IEM. Occurrence of adulterants and preservatives in the milk sold in rural areas of Omdurman, Sudan. Veterinary Medicine and Public Health Journal. 2021;2(3): 64–72.

35. Ibrahem SA, El Zubeir IE. Processing, composition and sensory characteristic of yoghurt made from camel milk and camel–sheep milk mixtures. Small Ruminant Research. 2016 Mar 1;136:109–12.

36. Rahman MA, Hossain A, Islam M, Hussain MS, Huque R. Microbial features and qualitative detection of adulteration along with physicochemical characteristics of sweetened yoghurt. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2020;12(4):9–16.

37. El Bakri JM, El Zubeir IEM. Chemical and microbiological evaluation of plain and fruit yoghurt in Khartoum State, Sudan. International Journal of Dairy Science. 2009;4(1):1–7.

38. Wu J, Jiang D, Wei O, Xiong J, Dai T, Chang Z, et al. Optimizing skim milk yogurt properties: Combined impact of transglutaminase and protein-glutaminase. Journal of Dairy Science. 2024 Nov 1;107(11):9087–99.

39. Oladipo IC, Atolagbe OO, Adetiba TM. Nutritional evaluation and microbiological analysis of yoghurt produced from full cream milk, tiger-nut milk, skimmed milk and fresh cow milk. Pensee. 2014 Apr;76(4):30–8.

40. Fahmid S, Sajjad A, Khan M, Jamil N, Ali J. Determination of chemical composition of milk marketed in Quetta, Pakistan. Int. J. Adv. Res. Biol. Sci. 2016;3(5):98–103.

41. Bilgin B, Kaptan B. A study on microbiological and physicochemical properties of homemade and small-scale dairy plant buffalo milk yoghurt. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Research Sciences. 2016;5(3):29–38.

42. Raymond MJ, Wohrle RD, Call DR. Assessment and promotion of judicious antibiotic use on dairy farms in Washington State. Journal of dairy science. 2006 Aug 1;89(8):3228–40.

43. El Zubeir IEM, El Owni OAO. Antimicrobial resistance of bacteria associated with raw milk contaminated by chemical preservatives World Journal of Dairy and Food Science. 2009;4(1): 65–9.

44. Derar AM, El Zubeir IE. Effect of fortifying camel milk with sheep milk on the processing properties, chemical composition and acceptability of cheeses. Journal of Food Science and Engineering. 2016;6:215–26.

45. Pazzola M, Stocco G, Dettori ML, Bittante G, Vacca GM. Effect of goat milk composition on cheesemaking traits and daily cheese production. Journal of dairy science. 2019 May 1;102(5):3947–55.

46. Mohamed OAE, El Zubeir IEM. Comparative study on chemical and microbiological properties of white cheese produced by traditional and modern factories. Annals of Food Science and Technology. 2018;19(1): 111–20.

47. El Zubeir IE, Jabreel SO. Fresh cheese from camel milk coagulated with Camifloc. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 2008 Feb;61(1):90–5.

48. Ishag HIJ, El Zubeir IEM. Processing and some phsico-chemical properties of white cheese made from camel milk using Capparis decidua fruits extract as a coagulant. Journal of Nutrition and Food Processing. 2022;5(3).

49. Kamal M, Foukani M, Karoui R. Rheological and physical properties of camel and cow milk gels enriched with phosphate and calcium during acid-induced gelation. Journal of Food Science and Technology. 2017 Feb;54(2):439–46.

50. Verdier-Metz I, Coulon JB, Pradel P. Relationship between milk fat and protein contents and cheese yield. Animal Research. 2001 Sep 1;50(5):365–71.

51. Feeney EL, Lamichhane P, Sheehan JJ. The cheese matrix: understanding the impact of cheese structure on aspects of cardiovascular health–a food science and a human nutrition perspective. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 2021 Nov;74(4):656–70.

52. Lemya MW, El Zubeir IE, El Owni O. Composition and hygienic quality of Sudanese white soft cheese in Khartoum North markets (Sudan). International Journal of Dairy Science. 2006;5:177–84.

53. Hamid OI, El Owni OA. Processing and properties of Sudanese white cheese (Gibna Bayda) in small-scale cheese units in South and West Darfur states (Sudan). Livestock Research for Rural Development. 2008 Aug 27;20(8):116.

54. Elkhider IAE, El Zubeir IEM, Basheir AA & Fadlelmoula AA. Composition and hygienic quality of Sudanese white cheese produced by small scale in rural area of eastern Sudan. Annals of Food Science and Technology. 2011;12 (2):186–92.

55. Suliman A, Abdalla ME, Zubeir IEM. Effect of Milk Fat Level on Salt, Some Mineral Content and Sensory Characteristic of Sudanese White Cheese During Storage. J Dairy Res Tech. 2019;2(008).

56. Politis I, Ng-Kwai-Hang KF. Effects of somatic cell count and milk composition on cheese composition and cheese making efficiency. Journal of Dairy Science. 1988 Jul 1;71(7):1711–9.

57. Nour El diam ASM & El Zubeir IEM. Chemical composition of processed cheese using Sudanese white cheese. Research Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences. 2010;5: 31–7.

58. Kaminarides S, Zagari H, Zoidou E. Effect of whey fat content on the properties and yields of whey cheese and serum. Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medical Society. 2020;71(2):2149–56.

59. Rudan MA, Barbano DM, Yun JJ, Kindstedt PS. Effect of fat reduction on chemical composition, proteolysis, functionality, and yield of Mozzarella cheese. Journal of dairy science. 1999 Apr 1;82(4):661–72.

60. Montgomery H, Haughey SA, Elliott CT. Recent food safety and fraud issues within the dairy supply chain (2015–2019). Global Food Security. 2020 Sep 1;26:100447.

61. Sharma R, Rajput YS, Poonam, Dogra G, Tomar SK. Estimation of sugars in milk by HPLC and its application in detection of adulteration of milk with soymilk. International journal of dairy technology. 2009 Nov;62(4):514–9.

62. Setyawardani T, Sumarmono J, Dwiyanti H. Preliminary investigation on the processability of low-fat herbal cheese manufactured with the addition of moringa, bidara, and bay leaves extracts. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 2022 Apr 1 (Vol. 1012, No. 1, p. 012081). IOP Publishing.

63. Gue M, Park WY, Dixon HP, Gilmore AJ, Kindstedt SP. Relationship between the yield of cheese (Chevre) and chemical composition of goat milk. International Dairy Journal. 2004;52(2):103–7.

64. Hamid OIA, El Owni OAO& Musa TM. Effect of salt concentration on weight loss chemical composition and sensory characteristics of Sudanese white cheese. Int J Dairy Science. 2008;3(2):79–85.

65. Abdalla MOM, Ahmed OI. Effect of heat treatment, level of sodium chloride, calcium chloride on the chemical composition of white cheese. Research J Animal and Vet Sciences. 2010;5:69–72.

66. Elkhider IA, El Zubeir IE, Basheir AA. The impact of processing methods on the quality of Sudanese white cheese produced by small scale in New Halfa area. Acta agriculturae Slovenica. 2012 Dec 17;100(2):131–7.

67. Guinee TP. Salting and the role of salt in cheese. International Journal of Dairy Technology. 2004 May;57(2‐3):99–109.

68. Akan E, Kinik O. Effect of mineral salt replacement on properties of Turkish White cheese. Mljekarstvo: Časopis za unaprjeđenje proizvodnje i prerade mlijeka. 2018 Jan 10;68(1):46–56.

69. Ayyash MM, Shah NP. Effect of partial substitution of NaCl with KCl on Halloumi cheese during storage: Chemical composition, lactic bacterial count, and organic acids production. Journal of Food Science. 2010 Aug;75(6):C525–9.

70. Soares C, Fernando AL, Alvarenga N, Martins AP. Substitution of sodium chloride by potassium chloride in São João cheese of Pico Island. Dairy Science & Technology. 2016 Sep;96(5):637–55.

71. Sheibani A, Ayyash MM, Shah NP, Mishra VK. The effects of salt reduction on characteristics of hard type cheese made using high proteolytic starter culture. International Food Research Journal. 2015 Nov 1;22(6):2452–9.

72. SSMO (2002). Sudanese Standards and Meteorology Organization. White Soft Cheese: Standard Number 1428.

73. Quintanilla P, Beltrán MC, Molina A, Escriche I, Molina MP. Characteristics of ripened Tronchón cheese from raw goat milk containing legally admissible amounts of antibiotics. Journal of dairy science. 2019 Apr 1;102(4):2941–53.

74. Escobar Gianni D, Pelaggio R, Cardozo G, Moreno S, De Torres E, Rey F, et al. Transfer of β-lactam and tetracycline antibiotics from spiked bovine milk to Dambo-type cheese, whey, and whey powder. Food Additives & Contaminants: Part A. 2023 Jul 3;40(7):824–37.

75. Payne MA, Craigmill A, Riviere JE, Webb AI. Extralabel use of penicillin in food animals. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2006 Nov 1;229(9):1401–3.

76. Warsma ML, Mustafa MEN, El Zubeir IEM. Antimicrabial resistance of bacteria associated with raw milk contaminated with antibiotics residues in Khartoum State, Sudan. Veterinary Medicine and Public Health Journal. 2020;1(1):15–21.

77. Said Ahmad AMM, El Zubeir IEM, El Owni OAO, Ahmed MKA. Assessment of microbial loads and antibiotic residues in milk supply in Khartoum State, Sudan. Research Journal of Dairy Sciences. 2008;2(3):36–41.

78. Sadighara P, Abedini AH, Irshad N, Ghazi-Khansari M, Esrafili A, Yousefi M. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and heavy metal exposure: a systematic review. Biological trace element research. 2023 Dec;201(12):5607–15.

79. Abedini AH, Vakili Saatloo N, Salimi M, Sadighara P, Alizadeh Sani M, Garcia-Oliviera P, et al. The role of additives on acrylamide formation in food products: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2024 Apr 14;64(10):2773–93.

80. Meerza SI, Gustafson CR. Does prior knowledge of food fraud affect consumer behavior? Evidence from an incentivized economic experiment. PloS one. 2019 Dec 3;14(12):e0225113.

81. Abedini A, Alizadeh AM, Mahdavi A, Golzan SA, Salimi M, Tajdar-Oranj B, et al. Oilseed cakes in the food industry; a review on applications, challenges, and future perspectives. Current Nutrition & Food Science. 2022 May 1;18(4):345–62.

82. Bouzembrak Y, Steen B, Neslo R, Linge J, Mojtahed V, Marvin HJ. Development of food fraud media monitoring system based on text mining. Food Control. 2018 Nov 1;93:283–96.

83. Spink J, Embarek PB, Savelli CJ, Bradshaw A. Global perspectives on food fraud: results from a WHO survey of members of the International Food Safety Authorities Network (INFOSAN). npj Science of Food. 2019 Jul 17;3(1):12.

84. Tibola CS, da Silva SA, Dossa AA, Patrício DI. Economically motivated food fraud and adulteration in Brazil: Incidents and alternatives to minimize occurrence. Journal of food science. 2018 Aug;83(8):2028–38.