Abstract

Background: Maternal hemorrhage represents the most prevalent complication and primary cause of mortality during childbirth. Extensive studies have elucidated noteworthy correlations between ABO blood type and cardiovascular disease risk in both genders. Notably, individuals with blood type O exhibit a substantial variation in the formation of the platelet plug on vascular lesions, accompanied by a reduction in von Willebrand factor.

Main outcome measures: The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the potential association between blood type O and an elevated risk of post-partum hemorrhage. Secondary objectives were indications of a distinctive medical history via a modified questionnaire, hemostasis disorders, and the utilization of transfusions. The delivery route, post-partum hemoglobin, gestity, and maternal age will also be studied.

Results: Group O comprises the majority in our sample, with 1,475 patients. Among carriers and non-carriers within group O, no significant differences were observed in demographic data. However, in laboratory analyses, there was a notable difference (P-value<0.05) in pre-delivery hemoglobin, hematocrit, and aPTT between group O carriers and non-carriers. Nevertheless, no significant associations were identified between group O and abnormal bleeding (P=0.1655), aPTT (P=0.0741), HEMSTOP score ≥2 (P=0,9337), or transfusion use (P=0.8206).

Conclusion: No correlation was found between having blood type O and an elevated risk of post-partum hemorrhage, hemostasis disorders, abnormal medical history according to the standardized HEMSTOP questionnaire, or a higher frequency of transfusion. Therefore, the recommended clinical approach for patients with blood type O remains unchanged.

Key Points

• In gynecology, the management of patients with group O remains unchanged.

• The utilization of the HEMSTOP questionnaire aids in identifying potential bleeding risks, allowing for the avoidance of unnecessary and unproven biological tests.

• The possible risk of resorting to transfusion must be prevented by knowledge of the ABO, Rhesus blood groups and the existence of irregular antibodies.

Introduction

During pregnancy, alterations in hemodynamic status and coagulability are observed. The Virchow triad, composed of venous stasis, vascular lesions, and hypercoagulability, contributes to an elevated risk of thromboembolus formation. This period also witnesses an increase in thrombin generation, clotting factors V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XII, and fibrinogen, alongside a decrease in natural anticoagulants such as proteins C and S. Platelet count generally remains stable or may even decrease. Fibrinolytic activity decreases in the 48 hours following delivery, enhancing clot stability during the early post-partum period. Women typically return to a normalized state within 4 to 6 weeks post-partum [1].

Maternal hemorrhage, defined as cumulative blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 ml or blood loss with signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours of delivery, remains the most prevalent complication and the leading cause of death during childbirth in the world [2-4], both levels of which persist during the post-partum period [4] and represent 19.7% [5]. Different definitions of coexisting post-partum hemorrhage, for this study, we decided to refer to the latter. In the United States, post-partum hemorrhage accounts for 11 to 12% of all maternal deaths, contributing significantly to peripartum medical and surgical morbidity [5]. Despite this, there has been notable improvement in this area over the past two decades, with decreased mortality associated with rising rates of transfusion and peri-partum hysterectomy [2-4], as well as the use of tranexamic acid [6]. The high prevalence of obstetric hemorrhage underscores the importance of managing demographic and medical risk factors with great vigilance [2-6].

In the general population, several studies have reported significant associations between ABO blood type and cardiovascular disease risk [7-8]. For instance, Rios et al. confirmed that ABO blood type is a crucial risk factor for increased procoagulant factors like FVIII and Von Willebrand factor in plasma among hemodialysis patients [8]. Moreover, research has demonstrated that individuals with blood group O experience a significantly reduced risk of thrombosis. The ABO group also significantly influences the formation of the platelet plug at the sites of vascular lesions during primary hemostasis, particularly at the level of Von Willebrand factor [7].

Plasma levels of Von Willebrand factor are approximately 25% lower in the healthy O group compared with non-O individuals in the same group. Additionally, individuals with blood type O exhibit an increased sensitivity to ADAMTS13 proteolysis. Preliminary results also suggest that the interaction of group O with platelets may be reduced [7]. All of this increases the risk of bleeding.

Studies by Langman and Doll have indicated that the ABO group influences the prognosis of peptic ulcers, with patients having blood group O being more susceptible to hemorrhage [9].

Before giving birth, it is ideal for pregnant women to undergo anesthesia consultation to screen for possible coagulopathy. Assessing the risk of bleeding associated with any obstetric intervention is a crucial step in minimizing the risk [10-12]. Therefore, a comprehensive history, encompassing personal and family details, along with a detailed clinical examination, is performed [10,12]. A biological examination of hemostasis should be prescribed selectively based on the assessment of these elements. It is noteworthy that standard tests such as prothrombin time, activated partial thrombosis time, and platelet count have a low positive predictor of bleeding risk in the general population [10,13].

A structured history is essential for obtaining a good predictive value. Fanny Bonhomme's team has developed the HEMSTOP questionnaire, which could serve as a solution (Table 1 – Appendix). This questionnaire is easily administered during anesthesia consultations, providing standardized, simple, quick, and effective screening [11,12]. Its prospective evaluation and validation were conducted in the HEMORISQ study involving 1,405 patients who underwent various interventions, excluding cardiac, neurological, vascular, thoracic, and obstetric surgeries [14,15]. The study demonstrated that the diagnostic performance of the structured bleeding risk questionnaire is acceptable, particularly in women [15].

A recent study, in which the author participated, indicated that a negative HEMSTOP questionnaire history correlated with a 96% specificity for peripartum blood loss [16]. In the study presented in this work, the focus is on pregnant women, aiming to assess whether blood type O is associated with an increased risk of post-partum hemorrhage and hemostasis disorders.

For the study presented in this work, we decided to target our population on pregnant women. Our goal is to evaluate whether blood group O is associated with an increased risk of post-partum hemorrhage (primary objective) as well as hemostasis disorders (secondary objective).

Materials and Methods

Literature review

We conducted a comprehensive search for relevant publications by exploring established electronic databases, including PubMed, Cochrane online library, and Google Scholar. The following key words were used: “blood type”, “post-partum hemorrhage”, “pregnancy”, “hemostasis”, “transfusion”, “obstetrics”. To enhance the scope of our investigations, we utilized tools such as HeTop to identify MeSH terms associated with our key topics. The search was not restricted by date or language, ensuring a thorough examination of available literature. Additionally, we cross-referenced article references to confirm that no significant publications had been overlooked, further bolstering the comprehensiveness of our literature review.

Study design

This study is a single-center retrospective investigation carried out at Brugmann University Hospital in Belgium. The collection of patient data was performed in accordance with the approval granted by the Ethics Committee of Brugmann Hospital, whose president is J. Valsamis MD, obtained on October 18, 2022, with reference CE2022/179. The study adhered to the protocol and principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring ethical standards and guidelines were followed in the research process.

Evaluation criteria and data collection

The study included patients who were over 18 years of age and had undergone pregnancy follow-up as per the guidelines recommended by the Centre of Expertise for Health Care (KCE) [17]. These patients gave birth either vaginally or by caesarean section within the period from 1st January 2020 to 31st December 2021.

Before inclusion, each patient underwent a consultation with an anesthetist, during which the objective was to gather personal and family medical history information and identify any ongoing treatments. As part of the prepartum assessment, a HEMSTOP questionnaire was administered (Table 1 – Appendix). This questionnaire is straightforward and unambiguous, comprising seven questions, two of which are tailored specifically for women. Patients provided binary responses to the questions, assigning a score of 1 for each positive response and 0 for each negative response. The questionnaire is considered positive when the total score is equal to or greater than 2 [11].

Excluded from the study were patients who had been subjected to treatment with anticoagulant and/or antiplatelet agents, as well as those with a language barrier. The demographic data collected for analysis included age, pre- and late-pregnancy weights, height, gestation, parity, ASA score, and gestational age.

Baseline hemostatic tests were conducted, encompassing activated partial thrombosis time (aPTT), prothrombin time (PT), fibrinogen level, and platelet count (PC). The criterion for considering the first-line hemostasis test as abnormal was established when any of the following elements exhibited irregularities: aPTT exceeding 28.7 seconds, PT falling below 70%, platelet count less than 75,000 g L-1, and fibrinogen level less than 1.5 g L-1.

Preparatory hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, as well as the initial post-partum hemoglobin and hematocrit control rates, were obtained from assessments conducted in the maternity ward. Birth canal and post-partum blood loss, with an abnormal threshold set at 1000 mL, was measured using clinical methods, including the use of a collection bag, intraoperative suction collection bowls, and the weighing of compresses to calculate the amount of blood loss.

ABO blood groups and associated rhesus-D factors were determined through testing at the blood bank. Two distinct groups were subsequently formed: patients with blood type O and patients with blood types other than O. The potential use of transfusion during the peripartum period was identified and considered if it was confirmed.

Detailed objectives

The primary objective of this study is to evaluate whether patients with blood type O are more prone to experiencing a severe episode of peripartum bleeding. The secondary objectives include investigating whether blood type O is linked to a more frequent positive outcome on the HEMSTOP questionnaire and examining its correlation with abnormal hemostasis. Birth canals as well as gestational age and maternal age as risk factors for post-partum hemorrhage will also be evaluated.

Additionally, tertiary objectives involve assessing whether blood type O is associated with a higher incidence of transfusion. The delivery route, post-partum hemoglobin, gestity, and maternal age will also be studied.

Given the substantial morbidity and mortality associated with both thrombotic and bleeding disorders, understanding the mechanisms underlying ABO group carriage is not only of scientific interest but also holds direct clinical importance.

Statistical analysis

For group comparisons, continuous data are compared using a T-test when variance homogeneity (tested using the Bartlett test) and residuals normality (tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test) are met. In this case, the means and standard deviations are presented. In the case where one of the two assumptions underlying the T-test (homogeneity of variance or normality of residuals) is not met, we perform a Wilcoxon rank sum test and the medians and inter-quartile deviations by group are presented. Finally, for discrete data, Pearson's Chi² test will be used and group proportions will be presented. A P-value <0.05 will be considered statistically significant. The R software (R Core Team, 2021), version 4.2.0. will be used to produce the results.

Results

Patient characteristics

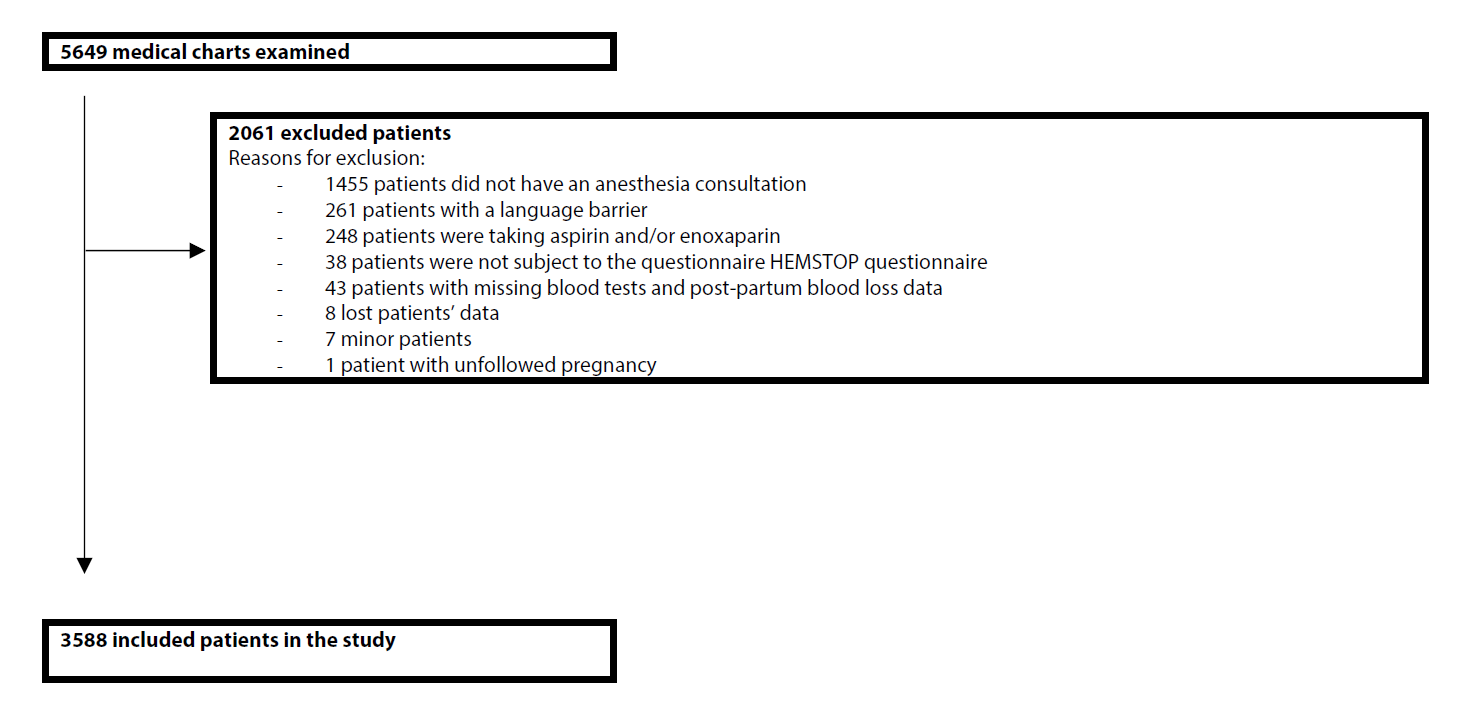

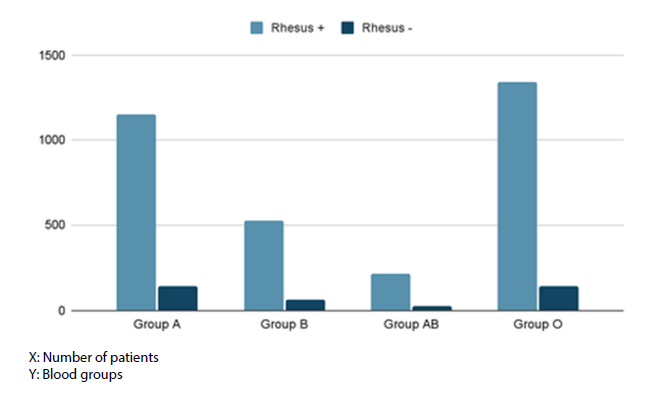

A total of 3,588 patients were included in this study (Figure 1). 1,153 patients have blood group A+, compared with 135 A-, there are 522 B+ groups and 66 B- groups. There are 213 patients with AB+ blood type and 27 with AB- blood type. Finally, there are 1,336 O+ and 136 O- groups (Figure 2). For the remainder of the description of the characteristics, the patients were divided into two groups: blood group O (n=1,472) and blood group non-O (n=2,116).

Figure 1: Flow chart of the study.

Figure 2: ABO and Rhesus blood groups distribution.

For the demographic characteristics of the study population, both groups exhibit an average age of 30 years, a gravidity of 2, parity of 1, and a gestational age of 39 weeks of amenorrhea. The height is recorded as 164 cm, and the pre-pregnancy and late pregnancy weights show a one-kilogram difference between the two groups (Table 1). None of these parameters demonstrate a statistically significant distinction between the two groups.

|

Variable |

Group non-O (n=2116) |

Group O (n=1472) |

P-value |

|

Age (years) |

30 [26–34] |

30 [26–34] |

0.08697 |

|

Pre-pregnancy weight (kg) |

65 [57–75] |

66 [58–76] |

0.2647 |

|

Weight at the end of pregnancy (kg) |

77 [69–87] |

78 [69–88] |

0.3382 |

|

Height (cm) |

164 [160–168] |

164 [160–168] |

0.1819 |

|

Gestity |

2 [1–3] |

2 [1–3] |

0.6897 |

|

Parity |

1 [0–2] |

1 [0–2] |

0.599 |

|

ASA |

2 [1–2] |

2 [1–2] |

0.4472 |

|

Gestational age (week of amenorrhea) |

39 [38–40] |

39 [38–40] |

0.9914 |

We identified a noteworthy contrast in several scrutinized variables, particularly prenatal hemoglobin and hematocrit, as well as activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT). This discrepancy can be attributed to the extensive size of the chosen study population and the low variability of the data. Concerning other biological data, no substantial differences were observed, and the means between the two groups exhibit remarkable similarity, if not identity (Table 2).

|

Variable |

Group non-O (n=2116) |

Group O (n=1472) |

P-value |

|

Pre-delivery hemoglobin (g dl-1) |

11.8 [11.1–12.6] |

11.9 [11.1–12.7] |

0.01389 |

|

Pre-delivery hematocrit (%) |

35.7 [33.6–37.6] |

35.9 [33.8–37.9] |

0.01026 |

|

Pre-delivery platelets (g L-1) |

214 [179–256] |

214 [177–258] |

0.7787 |

|

Pre-delivery PT (%) |

120 [112–131] |

120 [112–131] |

0.3734 |

|

Pre-delivery aPTT (seconds) |

24.2 [23–25.7] |

24.8 [23.6–26.4] |

<0.001 |

|

Normal aPTT, n (%) |

1996 (94.33%) |

1366 (92,80%) |

0.07414 |

|

Pre-delivery fibrinogen (g L-1) |

426 [211–474] |

422 [218–471] |

0.3386 |

|

Normal hemostasis report, n (%) |

1995 (94.28%) |

1364 (92.66%) |

0.05989 |

|

Post-partum hemoglobin (g dL-1) |

10.8 [10–11.8] |

10.9 [9.9–11.8] |

0.4877 |

|

Post-partum hematocrit (%) |

33.1 [30.5–35.6] |

33.1 [30.2–35.7] |

0.4299 |

Primary objective

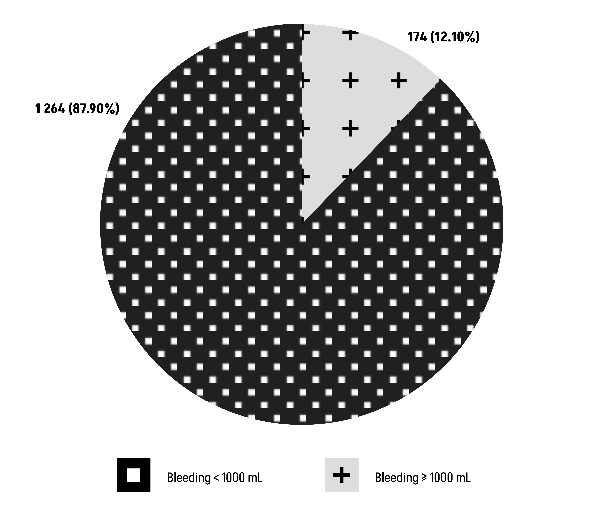

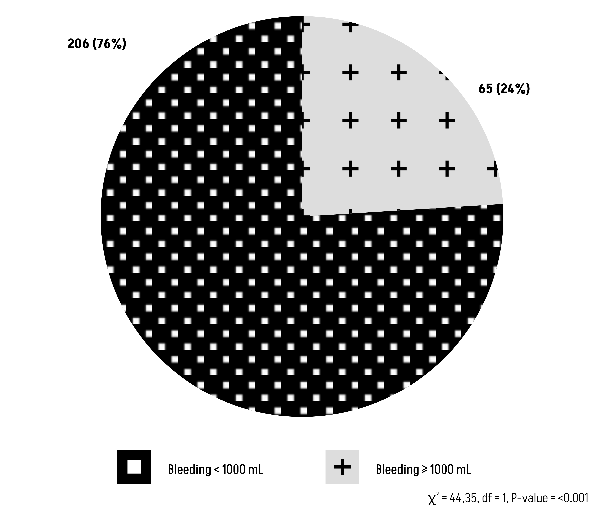

The Chi-square test results (χ²=1.9234, df=1) reveal a P-value of 0.1655, indicating that there is no statistically significant relationship between blood group O and abnormal bleeding (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of Group O with an abnormal bleeding ≥1000 mL.

Secondary objective (1)

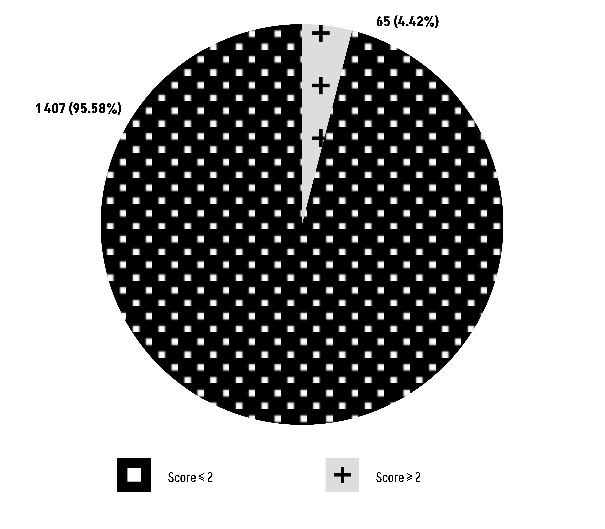

Group O vs HEMSTOP questionnaire score: The Chi-square test results (χ² = 0.0069247, df = 1) yield a P-value of 0.9337, indicating that there is no statistically significant relationship between blood group O and the scores obtained from the HEMSTOP questionnaire (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of Group O with the score of the HEMSTOP questionnaire.

Secondary objective (2)

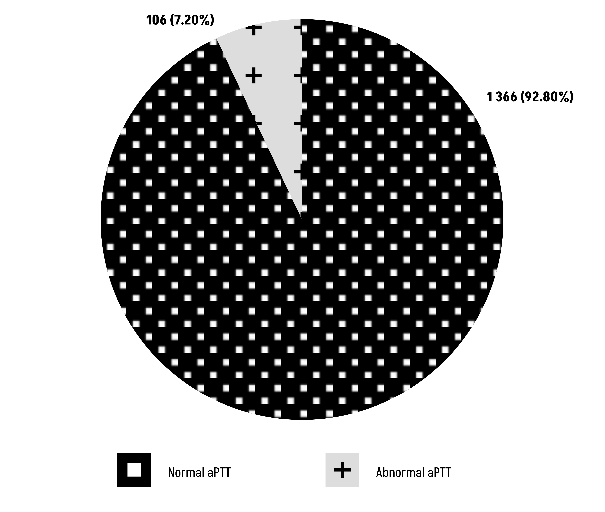

Group O versus aPTT: The Chi-square test results (χ² = 3.1888, df = 1) show a P-value of 0.07414, suggesting that there is no statistically significant relationship between blood group O and aPTT (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Comparison of Group O with aPTT.

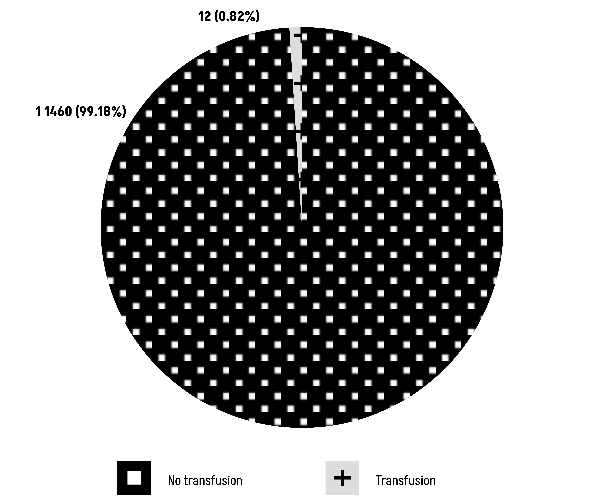

Tertiary objective (1)

The chi-square test, denoted as χ² = 0.051431 (df = 1), yields a P-value of 0.8206. This result conclusively suggests the absence of a statistically significant relationship between the presence of group O and the transfusion rate (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Comparison of Group O with transfusion rate.

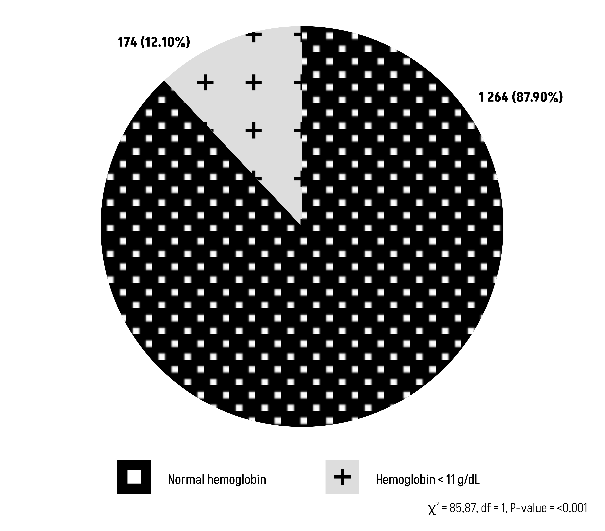

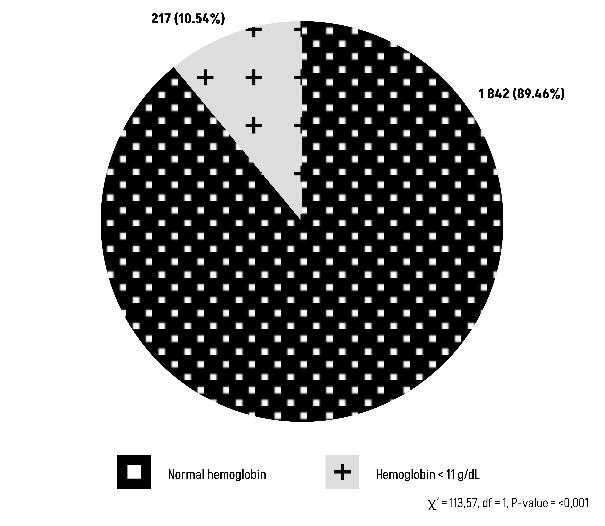

Tertiary objective (2)

The Chi-square test results suggest that there is statistically significant relationship between blood group O or non-O with post-partum hemoglobin level (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7: Comparison of Group O with post-partum hemoglobin level.

Figure 8: Comparison of Group non-O with post-partum hemoglobin level.

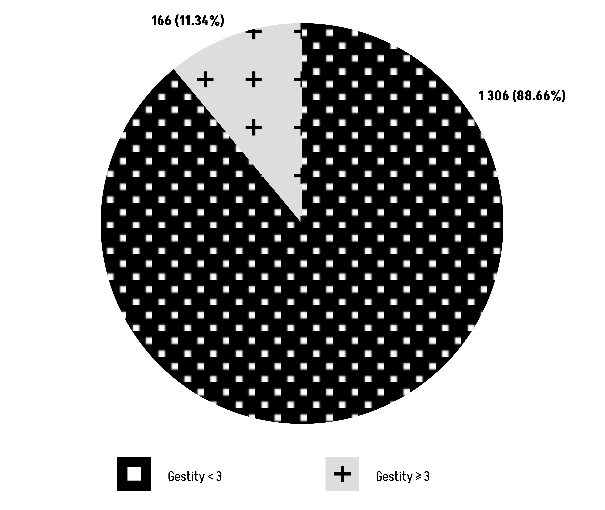

The Chi-square test results (χ² = 2,13, df = 1) show a P-value of 0.144, suggesting that there is no statistically significant relationship between blood group O and gestity (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Comparison of Group O with gestity.

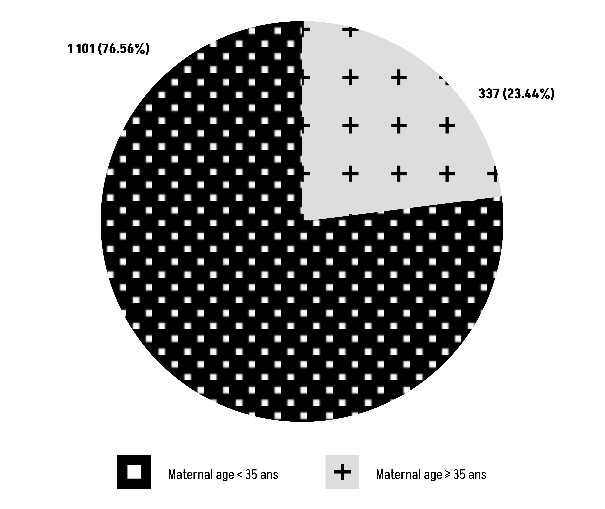

The Chi-square test results (χ² = 1,41, df = 1) show a P-value of 0.235, suggesting that there is no statistically significant relationship between blood group O and maternal age (Figure 10).

Figure 10: Comparison of Group O with maternal age.

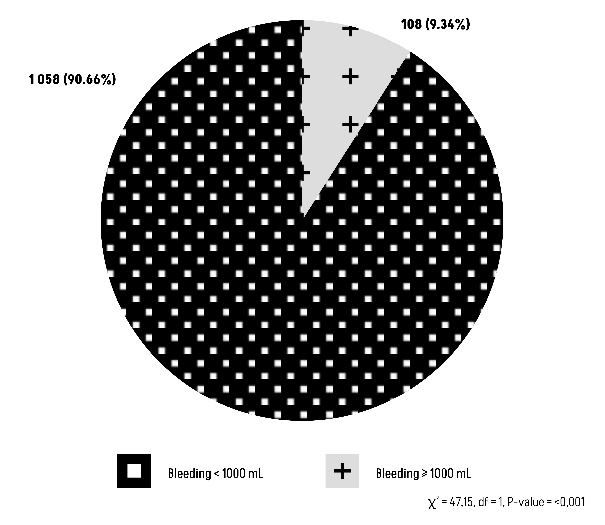

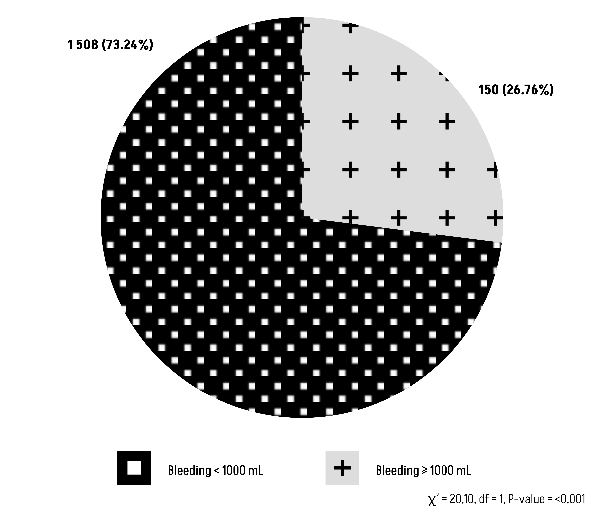

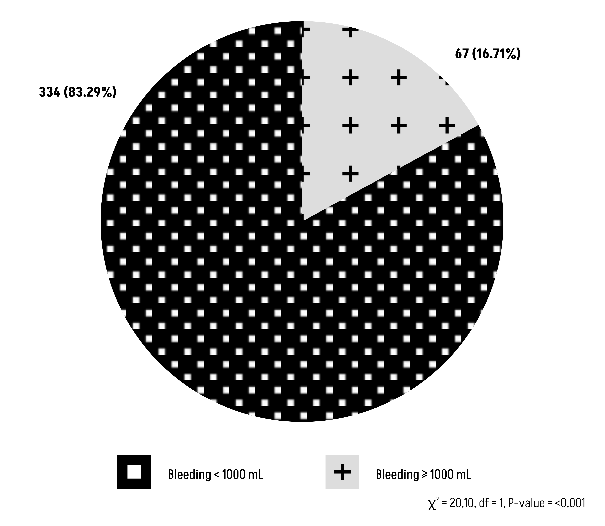

The Chi-square test results suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship between blood group O or non-O with peripartum blood loss during vaginal delivery (Figures 11 and 12).

Figure 11: Comparison of Group O with peripartum blood loss during vaginal delivery.

Figure 12: Comparison of Group non-O with peripartum blood loss during vaginal delivery.

The Chi-square test results suggest that there is a statistically significant relationship between blood group O or non-O with peripartum blood loss during cesarean delivery (Figures 13 and 14).

Figure 13: Comparison of Group O with peripartum blood loss during cesarean delivery.

Figure 14: Comparison of Group non-O with peripartum blood loss during cesarean delivery.

Discussion

In this retrospective study, our objective was to explore a potential association between blood type O and alterations in post-partum bleeding risk. We conducted thorough investigations into both historical and biological indicators of possible coagulation disorders. However, our statistical analysis revealed no discernible connection in our results.

It is important to emphasize that our sample is reflective of the global population, where blood group O predominates, followed by group A [18]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to acknowledge that these proportions may exhibit variation based on geographical locations.

Concerning the primary endpoint, the outcomes for post-partum hemorrhage revealed a minority proportion of patients with blood type O (12.10%) experiencing significant blood loss (Figure 3). This affirms that blood type O is not indicative of a predisposition to abnormal bleeding (P-value=0.1655).

Nevertheless, our study did not distinguish between patients with bleeding diatheses and those without in our population. It is evident that these pathologies could potentially influence the extent of blood loss. For example, elevated rates of post-partum hemorrhage have been documented in women with von Willebrand disease [19,20]. Our findings indicate that the risk of bleeding is not specifically correlated with blood type O.

Furthermore, recent investigations into individuals with left ventricular assist devices have revealed an elevated risk of bleeding in those with blood type O, possibly attributed to lower levels of Von Willebrand factor and factor VIII [21,22]. It is also important to acknowledge that during the gestation period, women exist in a pro-coagulant state [1], which contributes to a protective effect against hemorrhage. Notably, concentrations of clotting factors V, VII, VIII, IX, X, XII, fibrinogen, and Von Willebrand factor — the latter experiencing an increase from 133% to 376% during pregnancy—demonstrate significant elevation [23].

Concerning the secondary objective of our study, specifically the exploration of a potential association between blood group O and a positive HEMSTOP questionnaire, our observations revealed that among the 1,407 carriers of blood group O, 2,025 patients scored less than 2, in contrast to individuals without blood group O where a similar score was obtained (Figure 4).

It is noteworthy that in the study conducted by Bonhomme Fanny, the HEMSTOP questionnaire demonstrated a specificity of 98.6% and a sensitivity of 89.5% in detecting hemostatic disorders associated with a risk of hemorrhage [11].

Moreover, in the study conducted by Zec et al., the HEMSTOP questionnaire exhibited a specificity of 96% and a negative predictive value of 100% within a population of pregnant women. This same study allowed for the correlation of non-significant blood loss (<1000 mL) with the questionnaire score, demonstrating a specificity of 96% in cases with a negative history [16]. This aligns with existing literature indicating that conventional tests such as prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, and platelet count possess a low positive predictive value for bleeding risk in the general population [10,13,14].

Hence, a judicious and selective approach to prescribing preoperative tests or other investigations is recommended based on an individual's personal and family history of bleeding, as well as clinical evaluation during pre-natal anesthesia consultation [10,12,25-27]. If abnormalities are suspected, a hemostasis assessment should be conducted, and further investigation pursued if the results are pathological [28].

Congenital clotting factor deficiencies and platelet function disorders, which are linked to an increased risk of bleeding, exhibit a low overall prevalence in the general population [10].

Additionally, within the context of our secondary objective—exploring the potential association between blood type O and a hemostatic abnormality—we observe that the majority of patients with blood type O do not exhibit any coagulation abnormalities (Figure 5).

This aligns with existing studies indicating a significantly reduced risk of thrombotic events in individuals with blood type O [7], despite the procoagulant state induced by pregnancy [1].

Our tertiary objective aimed to investigate whether there exists a correlation between blood type O and an elevated risk of peripartum transfusion. However, our observations did not reveal any such relationship. It is acknowledged that the incidence of transfusion is quite low, ranging from 1 to 2.5% for vaginal deliveries and 3.1 to 5% for caesarean deliveries [29].

Peripartum hemorrhage stands as the foremost cause of maternal mortality and often occurs unexpectedly in women without specific risk factors [2,6,29]. Our study involved a relatively young and healthy population, can obviously have an impact on our findings. Similar to the risk of post-partum hemorrhage, we did not differentiate between patients with specific histories (such as bleeding-prone coagulopathy, previous post-partum hemorrhage, and prior caesarean sections), which could influence the extent of bleeding [30].

It's important to note that transfusion policies exhibit significant heterogeneity within obstetric services [28]. In the collaborating department, there was no standardized protocol, as the decision to transfuse was contingent upon the individual physician and the patient's clinical history.

The awareness of ABO and Rhesus blood groups, along with irregular antibodies in each parturient, is of paramount importance for preventing post-partum hemorrhage and transfusion-related complications [31].

The first measurement of post-partum hemoglobin showed a correlation with peripartum blood loss and O and non-O blood groups. This is a simple reflection that more or less significant blood loss impacts hemoglobin, making it decrease. In addition to this hemoglobin is also altered by pregnant status [32]. So, the O group is no more threatening than the non-O group.

A significant proportion of post-partum hemorrhages occur in the absence of recognized risk factors [33]. However, we know that multiparity as well as maternal age (>35 years) represent a significant risk factor for post-partum hemorrhage [33,34]. In this study, no relationship can be made between group O and gestation or maternal age >35 years. Our analysis focused solely on maternal risk factors. However, it is important to acknowledge that numerous other risk factors for PPH exist, including those associated with labor and delivery (e.g., instrumental delivery, placental abruption) as well as fetal factors (e.g., macrosomia, multiple pregnancy) [35].

Whether it is a vaginal delivery or a cesarean section, both are significant in terms of blood loss, regardless of blood type. In fact, this shows us that the amount of blood lost during childbirth does not depend on blood type.

It is noteworthy that the literature suggests significantly higher blood loss following a caesarean section compared with vaginal delivery [36].

In general, it is crucial to recognize the presence of various biases inherent in our study due to its retrospective and monocentric nature. Selection bias is common, as the inclusion of patients from a single center limits the representativeness of the sample. Measurement bias may arise from the retrospective collection of data from medical records, which may be incomplete or inconsistent. Confounding bias is also possible, as fully adjusting analyses for all confounding variables is challenging. Lastly, generalization bias reduces the applicability of the findings to other populations or settings, given the unique characteristics of the studied center.

Additionally, the exclusion of patients with language barriers resulted in the omission of certain available information.

We demonstrated the absence of any correlation between blood type O and an increased risk of post-partum hemorrhage, hemostatic disorders, abnormal medical history as indicated by the standardized HEMSTOP questionnaire, and a higher incidence of transfusion. This lack of association can be attributed to the compensatory factors, including the prothrombotic state inherent to the pregnant condition, which counteracts the hemorrhagic susceptibility associated with blood type O. Additionally, the utilization of the HEMSTOP questionnaire aids in identifying potential bleeding risks, allowing for the avoidance of unnecessary and unproven biological tests. Finally, the possible risk of resorting to transfusion must be prevented by knowledge of the ABO, Rhesus blood groups and the existence of irregular antibodies. Therefore, from a clinical standpoint, no supplementary measures are warranted for individuals with blood type O.

In our clinical practice, it is generally not necessary to take additional precautions for patients with blood type O, which helps avoid the use of more complex and costly tests for pregnant women in this group. However, it is important to note that the use of additional tests varies between hospital centers. Therefore, standardizing the use of the HEMSTOP questionnaire is a critical challenge, especially given its specificity of 96% and a negative predictive value of 100% in a population of pregnant women.

Disclosure

Absence of any interest to disclose.

Appendix

|

The following items may suggest the possibility of a hemostasis disorder |

YES |

NO |

|

1. Have you ever consulted a doctor or received treatment for prolonged or unusual bleeding (such as nosebleeds, minor wounds)? |

|

|

|

2. Do you experience bruises/hematomas larger than 2cm without trauma or severe bruising after minor trauma? |

|

|

|

3. After a tooth extraction, have you ever experienced prolonged bleeding requiring medical/dental consultation? |

|

|

|

4. Have you experienced excessive bleeding during or after surgery? |

|

|

|

5. Is there anyone in your family who suffers from a coagulation disease (such as hemophilia, von Willebrand disease, etc.)? |

|

|

|

6a. Have you ever consulted a doctor or received a treatment for heavy or prolonged menstrual periods (contraception pill, iron, etc.)? |

|

|

|

6b. Did you experience prolonged or excessive bleeding after delivery? |

|

|

References

2. Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 183: Post-partum Hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Oct;130(4):e168‑86.

3. Deneux-Tharaux C, Bonnet MP, Tort J. Épidémiologie de l'hémorragie du post-partum [Epidemiology of post-partum haemorrhage]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2014 Dec;43(10):936-50.

4. Patek K, Friedman P. Postpartum hemorrhage—Epidemiology, risk factors, and causes. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2023 Jun 1;66(2):344-56.

5. Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014 Jun;2(6):e323-33.

6. Sentilhes L, Daniel V, Deneux-Tharaux C, Houssin C, Madar H, Mattuizzi A, et al. TRAAP2 - TRAnexamic Acid for Preventing post-partum hemorrhage after cesarean delivery: a multicenter randomized, doubleblind, placebo- controlled trial – a study protocol. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020 Jan 31;20(1):63.

7. Ward SE, O'Sullivan JM, O'Donnell JS. The relationship between ABO blood group, von Willebrand factor, and primary hemostasis. Blood. 2020 Dec 17;136(25):2864-74.

8. Rios DR, Fernandes AP, Figueiredo RC, Guimarães DA, Ferreira CN, Simões E Silva AC, et al. Relationship between ABO blood groups and von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13 and factor VIII in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2012 May;33(4):416-21.

9. Langman MJ, Doll R. ABO blood group and secretor status in relation to clinical characteristics of peptic ulcers. Gut. 1965 Jun;6(3):270-3.

10. Bonhomme F, Ajzenberg N, Schved JF, Molliex S, Samama CM. Pre-interventional haemostatic assessment: Guidelines from the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care. European Journal of Anaesthesiology| EJA. 2013 Apr 1;30(4):142-62.

11. Bonhomme F, Françoise Boehlen MD PD, Clergue F, Philippe de Moerloose MD. Preoperative hemostatic assessment: a new and simple bleeding questionnaire. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2016 Sep 1;63(9):1007-15.

12. Ringuier CP, Samama CM. COMMENT ÉVALUER LE RISQUE HÉMORRAGIQUE EN PRÉOPÉRATOIRE?.

13. Eckman MH, Erban JK, Singh SK, Kao GS. Screening for the risk for bleeding or thrombosis. Ann Intern Med. 2003 Feb 4;138(3):W15-24.

14. Assistance Publique - Hôpitaux de Paris. Preoperative Haemorrhagic Risk Screening, Using a Standardized Questionnaire Before Scheduled Surgeries. [cité 17 févr 2023]. Report No.: NCT02617381. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02617381.

15. Congrès de la SFAR: Présentation des premiers résultats de l’étude HEMORISQ sur les performances diagnostiques du questionnaire préopératoire d’évaluation du risque de saignement periopératoire [Internet]. [cité 21 févr 2023]. Available at: https://www.aphp.fr/contenu/ congres-de-la-sfar-presentation-des-premiers-resultats-de-letude- hemorisq-sur-les.

16. Zec T, Schmartz D, Temmerman P, Fils JF, Ickx B, Bonhomme F, et al. Assessment of haemostasis in pregnant women: A retrospective evaluation of the diagnostic performance of the HEMSTOP standardised questionnaire. European Journal of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care. 2024 Apr 1;3(2):e0050.

17. Quels sont les examens recommandés pendant la grossesse ? | KCE [Internet]. 2015 [cité 19 févr 2023].

18. DOBSON AM, IKIN EW. The ABO blood groups in the United Kingdom; frequencies based on a very large sample. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1946 Apr;58:221-7.

19. Kazi S, Arusi I, McLeod A, Malinowski AK, Shehata N. Postpartum Hemorrhage in Women with von Willebrand Disease: Consider Other Etiologies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2022 Sep;44(9):972-7.

20. Majluf-Cruz K, Anguiano-Robledo L, Calzada-Mendoza CC, Hernández-Juárez J, Moreno-Hernández M, Domínguez-Reyes VM, et al. von Willebrand Disease and other hereditary haemostatic factor deficiencies in women with a history of postpartum haemorrhage. Haemophilia. 2020 Jan;26(1):97-105.

21. Tscharre M, Wittmann F, Kitzmantl D, Schlöglhofer T, Cichra P, Lee S, et al. Impact of ABO Blood Group on Thromboembolic and Bleeding Complications in Patients with Left Ventricular Assist Devices. Thromb Haemost. 2023 Mar;123(3):336-46.

22. Ewodo S, Nguefack CT, Adiogo D, Etong EM, Beyiha G, Belley PE. Variations de la concentration du facteur Von Willebrand au cours de la grossesse [Changes of Von Willebrand factor concentration during pregnancy]. Ann Biol Clin (Paris). 2014 May-Jun;72(3):292-6. French.

23. Bremme KA. Haemostatic changes in pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2003 Jun;16(2):153-68.

24. Chee YL, Crawford JC, Watson HG, Greaves M. Guidelines on the assessment of bleeding risk prior to surgery or invasive procedures. British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2008 Mar;140(5):496-504.

25. Perez A, Planell J, Bacardaz C, Hounie A, Franci J, Brotons C, Congost L, Bolibar I. Value of routine preoperative tests: a multicentre study in four general hospitals. Br J Anaesth. 1995 Mar;74(3):250-6.

26. Kaplan EB, Sheiner LB, Boeckmann AJ, Roizen MF, Beal SL, Cohen SN, et al. The usefulness of preoperative laboratory screening. JAMA. 1985 Jun 28;253(24):3576-81.

27. Borges NM, Thachil J. The relevance of the coagulation screen before surgery. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2017 Oct 2;78(10):566-70.

28. Prégaldien A, Dewandre PY, Brichant JF. Faut-il prescrire systématiquement un bilan d'hémostase avant la réalisation d'une péridurale analgésique pour le travail en obstétrique?. Revue Médicale de Liège. 2010;65(1).

29. Georges A, Dan B, Bruno C, Jacques C, Françoise C, Anne-Sophie DB, et al. Table ronde réunie le 26 septembre 2000.

30. Benhamou D. Transfusion de plasma thérapeutique: produits, indications. Actualisation 2012 [Plasma transfusion: products and indications. 2012 guidelines update]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2012 Nov;19(4-5):253-62. French.

31. Adukauskienė D, Veikutienė A, Adukauskaitė A, Veikutis V, Rimaitis K. The usage of blood components in obstetrics. Medicina (Kaunas). 2010;46(8):561-7.

32. Tchente CN, Tsakeu EN, Nguea AG, Njamen TN, Ekane GH, Priso EB. Prevalence and factors associated with anemia in pregnant women attending the General Hospital in Douala. The Pan African Medical Journal. 2016 Nov 4;25:133.

33. Ende HB, Lozada MJ, Chestnut DH, Osmundson SS, Walden RL, Shotwell MS ,et al. Risk Factors for Atonic Postpartum Hemorrhage: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Feb 1;137(2):305-23.

34. Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, Dahhou M, Rouleau J, Mehrabadi A, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Nov;209(5):449.e1-7.

35. Escobar MF, Nassar AH, Theron G, Barnea ER, Nicholson W, Ramasauskaite D, et al; FIGO Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Committee. FIGO recommendations on the management of postpartum hemorrhage 2022. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2022 Mar;157 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-50.

36. Misme H, Dupont C, Cortet M, Rudigoz RC, Huissoud C. Analyse descriptive du volume des pertes sanguines au cours de l’accouchement par voie basse et par césarienne. Journal de Gynécologie Obstétrique et Biologie de la Reproduction. 2016 Jan 1;45(1):71-9.