Abstract

Groundwater has been an invaluable resource for humanity for centuries. India is the world’s largest user of groundwater. It is mostly used not only for drinking and cooking but also for miscellaneous domestic purposes and irrigation in agriculture. Hand-pumps, bore-wells, step-wells, and open deep dug-wells continue to be the primary and major sources of groundwater production in India. However, in rural areas of the country, hand-pumps are the most common and major drinking water sources for households. According to a survey, 42.9% of households in rural areas use hand- pumps as their main source of drinking water, while 40.9% of households in urban areas use piped or surface water as their main source. In rural India, >90% of drinking groundwater sources are naturally contaminated with varying amounts of fluoride. In India, groundwater of 23 out of 37 states and union territories is found to be fluoridated. Among these, 70-100% districts in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Telangana and 40-70% districts in the rest of the states have fluoride-contaminated groundwater with maximum permissible levels >1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm. Such water is not at all safe for human health, even for the health of animals. In fact, drinking such water for a long period of time, a dangerous disease called fluorosis (hydrofluorosis) develops. Due to fluorosis, people's teeth become weak and discoloured (dental fluorosis) and their bones become hollow and weak (skeletal fluorosis). Due to the development of fluoride-induced deformities in various bones, people become hunchbacked and eventually start walking with a limp. These anomalies are, generally, permanent, irreversible, and incurable and persist throughout life. According to the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Fluorosis (NPPCF), the population at risk based on population in habitations with high fluoride in drinking water is >11.7 million in the country. However, NGOs have warned that the threat is far more widespread, affecting more than 60 million people across the country. In the current communication focuses on how safe drinking groundwater is for human health in India and also draws attention to those responsible for addressing this drinking water health problem.

Keywords

Bore-wells, Dental fluorosis, Groundwater, Hand-pumps, Human health, Hydrofluorosis, Fluoride, Non-skeletal fluorosis, Open dug-wells, Rural India, Skeletal fluorosis, Step-wells

Introduction

Groundwater has been an invaluable resource for humanity for centuries. India is the world’s largest user of groundwater. It is mostly used not only for drinking and cooking but also for miscellaneous domestic purposes and irrigation in agriculture. Hand-pumps, bore-wells, step-wells, and open deep dug-wells (Figures 1a-1h) continue to be the primary sources of groundwater production in India. However, in rural India, the most common and major drinking water sources for households are hand-pumps. Before the 80s, step-wells and open deep dug-wells were the main sources of drinking water in almost every state and union territories of India. Since at that time, outbreak of the disease called dracunculiasis, caused by infection with the human nematode worm, Dracunculus-worm (Dracunculus medinensis), was also high in India, especially in its rural areas [1-3]. This disease was spread in the rural areas of many states by drinking the water of these groundwater sources. To eradicate this disease, thousands of hand-pumps and bore-wells were dug at various places to provide clean water by closing these traditional water sources. That is why, these water sources are found in abundance in the rural areas of the country [4,5].

Figure 1. The most common drinking groundwater sources in the rural areas of India. Hand-pumps (a and b), bore-wells (c and d), step-wells (e and f), and open deep dug-wells (g and h).

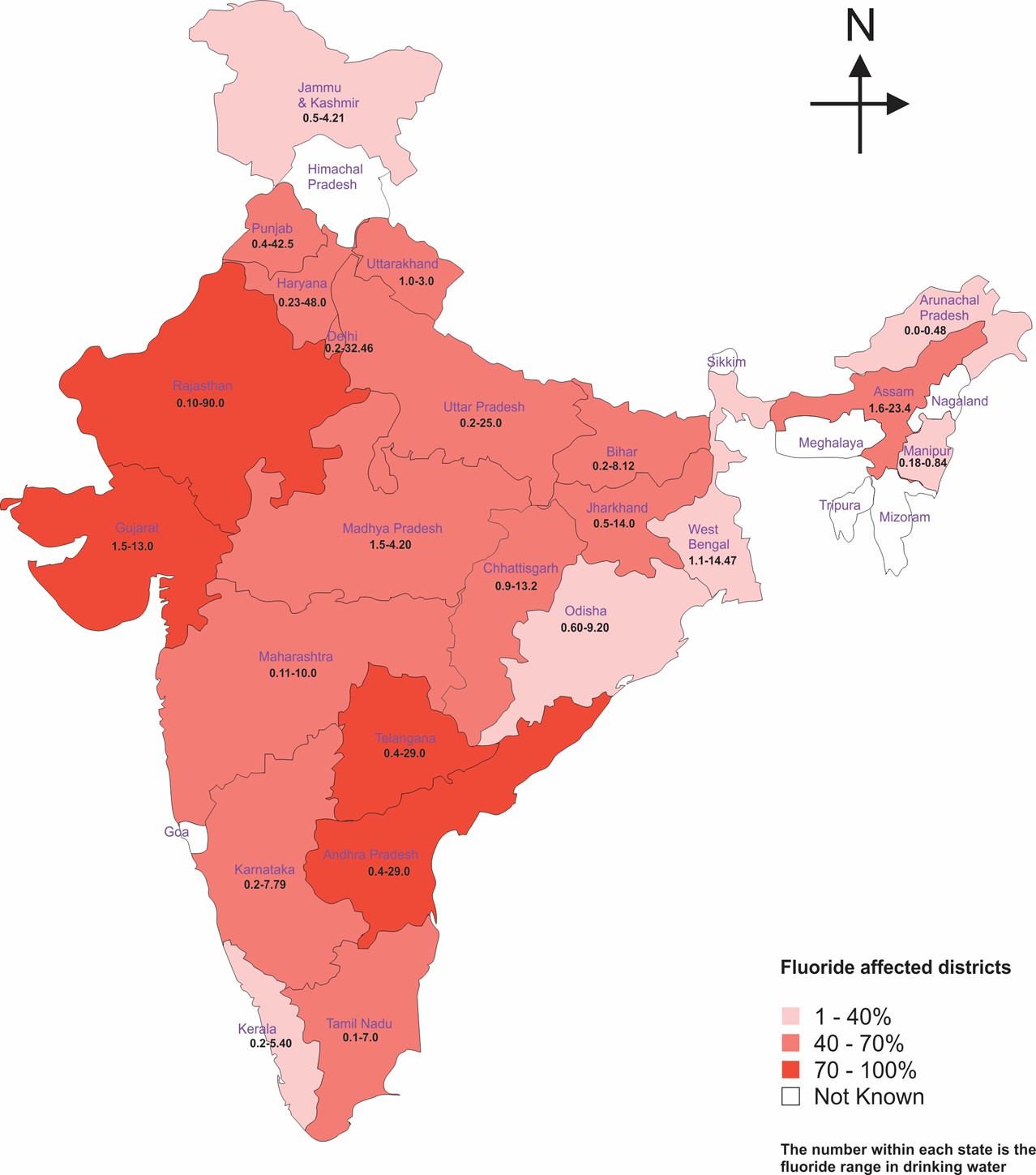

According to the National Sample Survey (NSS) report on drinking water, sanitation, hygiene, and housing condition, 42.9% of households in rural areas use hand- pumps as their main source of drinking water, while 40.9% of households in urban areas use piped or surface water as their main source [6]. In rural India, >90% of drinking groundwater sources is contaminated with varying amounts of fluoride. In the country, groundwater of 23 out of 37 states and union territories is found to be contaminated with fluoride with varying amounts. Among these, 70-100% districts in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Telangana and 40-70% districts in the rest of the states have fluoride-contaminated groundwater [4,5] with maximum permissible levels >1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm [7-9]. The fluoride distribution with varying level in different states and union territories has been shown in Figure 2. Such water or fluoride containing groundwater is not at all safe for human health, even for the health of domestic animals. Drinking such water for a long time develops a dangerous disease called fluorosis (hydrofluorosis) in human beings [7,10-12]. Due to which the teeth of humans become weak, defragmented, and discoloured (dental fluorosis), while they also become victims of lameness (skeletal or crippling fluorosis) [13-15]. In fact, these fluoride-induced changes or deformities in teeth and bones are permanent and irreversible and remain in humans for life. More importantly, there is no cure available for these changes. In the current communication focuses on how safe drinking groundwater is for human health in India and also draws attention to those responsible for addressing this drinking water health problem.

Figure 2. Map of India showing fluoride (in ppm) contamination of drinking groundwater in different states and union territories (Source: Reference number 5).

Is Drinking Groundwater Safe for Human Health?

Fluoride has a potential role in the mineralization of developing teeth and is beneficial in preventing dental caries [7,16,17]. But when people repeatedly drink water with fluoride levels above 1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm over a long period of time, it becomes toxic to the body [7]. Due to its toxic effect, many types of physical disorders or deformities develop in humans. These disorders are collectively referred to as fluorosis [7]. This means that people who drink or have been drinking groundwater for a long time have a higher risk of developing fluorosis (hydrofluorosis) than people who drink surface water (ponds, rivers, dams, etc.), which is usually free of fluoride. Because the groundwater of hand-pumps and bore-wells in most rural areas of India is fluoridated, in which the amount of fluoride is more than the safe level or permissible limit, 1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm. That is why in rural India, wherever the amount of fluoride in groundwater exceeds the prescribed parameters, it is harmful and unsafe for human health. The reason for fluorosis being endemic in most of the rural areas is the groundwater itself, drinking of which this disease is commonly seen in people. According to the National Programme for Prevention and Control of Fluorosis (NPPCF) the population at risk based on population in habitations with high fluoride in drinking water is > 11.7 million in the country [18]. However, NGOs have warned that the threat is far more widespread, affecting more than 60 million people. However, in India, the maximum and outstanding research work on fluoride distribution in drinking groundwater and its chronic intoxication or endemic fluorosis has been done in the state of Rajasthan, especially in the scheduled area where more tribals are residing [19-28].

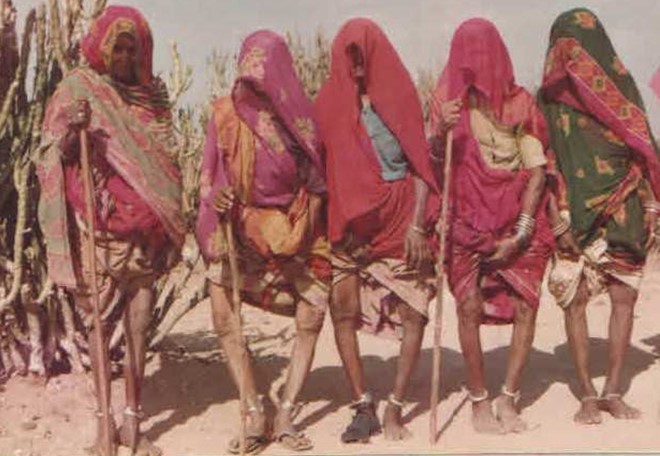

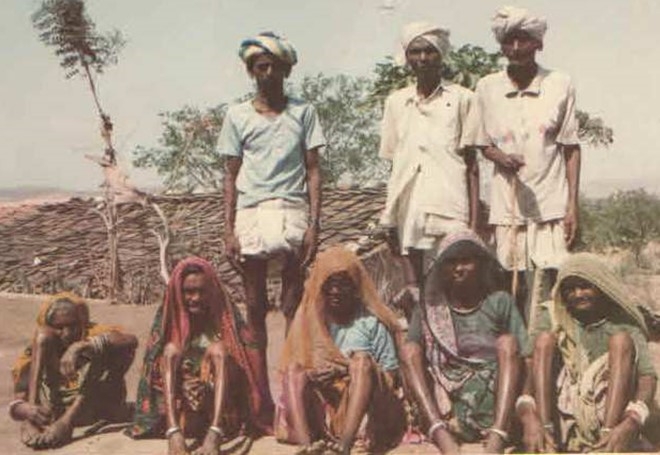

In fluorosis, the teeth become weakened, defragmented, and discoloured light to deep brownish (dental fluorosis) and crippling deformity (skeletal fluorosis) due to diverse bony changes are the main features among fluorosed people. In fluorosis, people's teeth become light to dark brown in colour (Figure 3), and people become disfigured (Figures 4a and 4b), due to various changes in their bones such as periosteal exostosis, osteosclerosis, osteoporosis, osteophytosis, etc. [29-31]. These anomalies in the teeth and bones are permanent and last for life. Apart from these, many types of health problems (non-skeletal fluorosis) such as gastro-intestinal discomforts, anaemia, body weakness, polydipsia, polyuria, repeated abortion, impaired reproduction and endocrines, neurological disorders, etc. also develop in people of all age groups from drinking of fluoridated groundwater or suffering with fluorosis [7, 26]. Although, these fluoride- induced health problems are temporary, however, these are significant and helpful in the diagnosis of chronic fluoride intoxication not only in humans [32] but also in domestic animals [33]. However, the severity and prevalence of fluorosis depends on many factors other than the amount of fluoride in the drinking water and its duration and frequency of exposure, and density or rate of bio-accumulation. The most common and potential determinants are found to be chemical constituents in drinking water, age, gender, habits, food constituents, environmental factors, and individual susceptibility, biological response or tolerance, health, and genetics [34-43].The special thing is that due to the easy availability of water from hand-pumps and bore-wells, the villagers also started feeding water from these water sources to their domesticated animals, cattle (Bos taurus), water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis), sheep (Ovis aries), goats (Capra hircus), dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius), horses (Equus caballus), and donkeys (Equus asinus), due to which these domesticated animals also started getting fluorosis disease [44-65]. Due to which these animal herders are also facing financial loss, which is not known to these people. Not only has this, irrigating agriculture with fluoridated groundwater also caused mild to severe damage to various agriculture crops, which also affects agricultural production or yield [66-71]. “Overall, fluoridated groundwater in most rural areas of India is unsafe and harmful not only to humans but also to the health of domestic animals and agricultural crops”.

Figure 3. A young villager afflicted with severe dental fluorosis due to drinking of fluoridated groundwater in the state of Rajasthan, India characterised with bilateral strati?ed deep brownish staining of anterior teeth (Source: Reference number 26).

Figure 4. Villagers are afflicted with moderate to severe skeletal fluorosis due to drinking of fluoridated groundwater characterised with invalidism, kyphosis, genu-varum (outward bowing of legs at the knee), crippling deformity, and paraplegia and quadriplegia in women sitting down (Source: Reference no. 23).

How can Fluoride Free Drinking Water be Made Available to the People?

In rural India, fluoride-free drinking water can be provided to the human population at both the community and household or domestic levels by adopting appropriate defluoridation techniques. Although several defluoridation techniques are available in India. However, one of them, the “Nalgonda defluoridation technique” is most suitable, ideal, appropriate, and effective and is also less expensive [72]. Although, this technique is cheaper and gives better results than other techniques but its success rate at community level is still very poor and at many places it is totally failure due to lacking proper monitoring, maintenance, taking responsibility, and perfect handling. However, author believe that instead these efforts, harvesting and conservation of rain water is the most ideal method to get regular fluoride- free water for drinking and cooking purposes in rural communities. Another effective option is to supply treated surface waters from perennial reservoirs, ponds, dams, rivers, etc.

Conclusion

In rural India, the groundwater is used not only for drinking and cooking but also in agriculture sector. Hand-pumps, bore-wells, step- wells, and open deep dug- wells continue to be the principal sources of groundwater production in India. However, the commonest and principal drinking groundwater sources for households are hand-pumps and bore-wells. Rural areas of 23 out of 37 states and union territories are contaminated with varying degrees of fluoride. Most of the groundwater of these drinking water sources has fluoride beyond the maximum permissible or safe limit, 1.0 ppm or 1.5 ppm. Prolonged use of such water for drinking and cooking is unsafe and harmful for human health and causes the dreaded fluorosis disease. In fact, fluoridated water not only damages the teeth (dental fluorosis) and various bones (skeletal or crippling fluorosis) of the body, but it also damages various organs (non-skeletal fluorosis) of the body. In the country, > 11.7 million humans are at the risk of this serious fluorosis disease. However, this endemic fluorosis or public health problem can be controlled by providing fluoride free water to the rural population. Such water can be prepared by “Nalgonda defluoridation technology” both at community and household level. Fluoride-free drinking water can also be provided to villagers through rainwater harvesting and conservation, and supply of treated surface water from perennial reservoirs, dams, rivers, etc.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Dr. Pallavi Choubisa, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, R.N.T. Medical College and Pannadhay Zanana Hospital, Udaipur, Rajasthan 313002, India for cooperation.

References

2. Choubisa SL, Verma R, Choubisa L. Dracunculiasis in tribal region of southern Rajasthan, India: a case report. Journal of Parasitic Diseases. 2010 Oct;34(2):94-6.

3. Choubisa SL. A Historical Dreaded Human Nematode Parasite, Dracunculus Worm (Dracunculus medinensis) Whose Awe is Still Alive in Elderly of India. Can’t it Reappear in India? Austin Public Health. 2022; 6(1):1-4, id1019.

4. Choubisa SL. Fluoride distribution in drinking groundwater in Rajasthan, India. Current Science. 2018 May 10:1851-7.

5. Choubisa SL. A brief and critical review on hydrofluorosis in diverse species of domestic animals in India. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2018 Feb;40(1):99-114.

6. NSO. Drinking Water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Housing Condition, National Sample Survey (NSS) report number 584, The National Statistical Office (NSO), Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation, Government of India, New Delhi, India. 2019.

7. Adler P, Armstrong WD, Bell ME, Bhussry BR, Büttner W, Cremer H-D, et al. Fluorides and human health. World Health Organization Monograph Series No. 59. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1970.

8. ICMR. Manual of standards of quality for drinking water supplies. Special report series No. 44, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India, 1974.

9. BIS. Indian standard drinking water-specification. 2nd revision. New Delhi: Bureau of Indian Standards, 2012.

10. Choubisa SL, Choubisa DK, Joshi SC, Choubisa L. Fluorosis in some tribal villages of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 1997 Nov;30(4):223-8.

11. Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa DK. Endemic fluorosis in Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Environmental Health. 2001 Oct 1;43(4):177-89.

12. Choubisa SL. Endemic fluorosis in southern Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2001 Feb 1;34(1):61-70.

13. Choubisa SL. Fluorosis in some tribal villages of Udaipur district (Rajasthan). Journal of Environmental Biology. 1998 Oct 1;19(4):341-52.

14. Choubisa SL. Chronic fluoride intoxication (fluorosis) in tribes and their domestic animals. International Journal of Environmental Studies. 1999 Aug 1;56(5):703-16.

15. Choubisa SL, Sompura K. Dental fluorosis in tribal villages of Dungarpur district (Rajasthan). Pollution Research. 1996; 15(1):45-7.

16. Medjedovic E, Medjedovic S, Deljo D, Sukalo A. Impact of fluoride on dental health quality. Materia Socio-Medica. 2015 Dec;27(6):395-8.

17. Pollick H. The role of fluoride in the prevention of tooth decay. Pediatric Clinics. 2018 Oct 1;65(5):923-40.

18. NPPCF. National Programme for Prevention & Control of Fluorosis, National Health Mission, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, New Delhi, India, 2014.

19. Choubisa SL, SOMPURA K, Choubisa DK, PANDYA H, Bhatt SK, Sharma OP. Fluoride content in domestic water sources of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Environmental Health. 1995;37(3):154-60.

20. Choubisa SL, Sompura K, Bhatt SK, Choubisa DK, Pandya H, Joshi SC. Prevalence of fluorosis in some villages of Dungarpur district of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Environmental Health. 1996;38(2):119-26.

21. Choubisa SL, Sompura K, CHOUBISA D, Sharma OP. Fluoride in drinking water sources of Udaipur district of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Environmental Health. 1996;38(4):286-91.

22. Choubisa SL, Verma R. Skeletal fluorosis in bone injury case. Journal of Environmental Biology. 1996 Jan 1;17:17-20.

23. Choubisa SL. An epidemiological study on endemic fluorosis in tribal areas of southern Rajasthan. A technical report. The Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, New Delhi, 1996, pp 1-84.

24. Choubisa SL. Fluoride distribution and fluorosis in some villages of Banswara district of Rajasthan. Indian Journal of Environmental Health. 1997;39(4):281-8.

25. Choubisa SL. Fluoride in drinking water and its toxicosis in tribals of Rajasthan, India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 2012 Jun;82:325-30.

26. Choubisa SL. A brief and critical review of endemic hydrofluorosis in Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2018;51(1):13-33.

27. Choubisa SL, Choubisa D. Genu-valgum (knock-knee) syndrome in fluorosis-endemic Rajasthan and its current status in India. Fluoride. 2019 Apr 1;52(2):161-8.

28. Choubisa SL. Status of chronic fluoride exposure and its adverse health consequences in the tribal people of the scheduled area of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2022;55(1):8-30.

29. Choubisa SL. Radiological skeletal changes due to chronic fluoride intoxication in Udaipur district, Rajasthan. Pollution Research. 1996;15:227-9.

30. Choubisa SL. Toxic effects of fluoride on bones. Advances in Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2012; 13(1):9-13.

31. Choubisa SL. Radiological Findings More Important and Reliable in the Diagnosis of Skeletal Fluorosis. Austin Medical Sciences. 2022;7(2):1-4, id1069.

32. Choubisa SL. The diagnosis and prevention of fluorosis in humans. Journal ISSN. 2022;2766:2276.

33. Choubisa SL. How Can Fluorosis in Animals be Diagnosed and Prevented? Austin Journal of Veterinary Science & Animal Husbandry. 2022;9(3):1-5, id1096.

34. Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Sompura K, Choubisa D. Fluorosis in subjects belonging to different ethnic groups of Rajasthan, India. The Journal of Communicable Diseases. 2007 Sep 1;39(3):171-7.

35. Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to nutritional status, living habits, and occupation in rural tribal areas of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2009 Jul 1;42(3):210-5.

36. Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to age and sex in tribal districts of Rajasthan, India. Journal of Environmental Science & Engineering. 2010 Jul 1;52(3):199-204.

37. Choubisa SL. Natural amelioration of fluoride toxicity (fluorosis) in goats and sheep. Current Science. 2010;99(10):1331-2.

38. Choubisa SL, Choubisa L, Choubisa D. Reversibility of natural dental fluorosis. International Journal of Pharmacology & Biological Sciences. 2011 Aug 1; 5(20):89-93.

39. Choubisa SL, Mishra GV, Sheikh Z, Bhardwaj B, Mali P, Jaroli VJ. Food, fluoride, and fluorosis in domestic ruminants in the Dungarpur district of Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2011 Apr 1;44(2):70-6.

40. Choubisa SL. Osteo-dental fluorosis in relation to chemical constituents of drinking waters. Journal of Environmental Science & Engineering. 2012 Jan 1;54(1):153-8.

41. Kinkrawali L, Morzonda N. Why desert camels are least afflicted with osteo-dental fluorosis?. Current Science. 2013 Dec 25;105(12):1671-2.

42. Choubisa SL. Bovine calves as ideal bio-indicators for fluoridated drinking water and endemic osteo-dental fluorosis. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 2014 Jul;186(7):4493-8.

43. Choubisa SL, Choubisa A. A brief review of ideal bio-indicators, bio-markers and determinants of endemic of fluoride and fluorosis. Journal of Biomedical Research and Environmental Sciences. 2021;2(10):920-25.

44. Choubisa SL, Pandya H, Choubisa DK, Sharma OP, Bhatt SK, Sompura K, et al. Osteo-dental fluorosis in bovines of tribal region in Dhungarpur (Rajasthan). Journal of Environmental Biology. 1996 Apr 1;17(2):85-92.

45. Choubisa SL. Some observations on endemic fluorosis in domestic animals in Southern Rajasthan (India). Veterinary Research Communications. 1999 Nov;23:457-65.

46. Choubisa SL. Fluoride toxicity in domestic animals in Southern Rajasthan. Pashudhan. 2000; 15(4):5.

47. Choubisa SL. Fluoridated ground water and its toxic effects on domesticated animals residing in rural tribal areas of Rajasthan, India. International Journal of Environmental Studies. 2007 Apr 1;64(2):151-9.

48. Choubisa SL. Osteo-dental fluorosis in domestic horses and donkeys in Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2010 Jan 1;43(1):5-10.

49. Choubisa SL. Fluorosis in dromedary camels in Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2010 Jul 1;43(3):194-9.

50. Choubisa SL, Mishra GV, Sheikh Z, Bhardwaj B, Mali P, Jaroli VJ. Toxic effects of fluoride in domestic animals. Advances in Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2011;12(2):29-37.

51. Choubisa SL, Modasiya V, Bahura CK, Sheikh Z. Toxicity of fluoride in cattle of the Indian Thar Desert, Rajasthan, India. Fluoride. 2012 Oct 1;45(4):371-6.

52. Choubisa SL. Status of fluorosis in animals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 2012 Sep;82:331-9.

53. Choubisa SL. Fluorotoxicosis in diverse species of domestic animals inhabiting areas with high fluoride in drinking water of Rajasthan, India. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, India Section B: Biological Sciences. 2013 Sep;83(3):317-21.

54. Choubisa SL, Mishra GV. Fluoride toxicosis in bovines and flocks of desert environment. International Journal of Pharmacology and Biological Sciences. 2013; 7(3):35-40.

55. Choubisa SL. Fluoride toxicosis in immature herbivorous domestic animals living in low fluoride water endemic areas of Rajasthan, India: an observational survey. Fluoride. 2013; 46(1):19-24.

56. Choubisa SL. Chronic fluoride exposure and its diverse adverse health effects in bovine calves in India: an epitomised review. Global Journal of Biology, Agriculture and Health Sciences. 2021; 10(3):1-6, 10:107.

57. Choubisa SL. A brief and critical review of chronic fluoride poisoning (fluorosis) in domesticated water buffaloes (Bubalus bubalis) in India: focus on its impact on rural economy. Journal of Biomedical Research and Environmental Sciences.2022; 3(1):96-104.

58. Choubisa SL. A brief review of chronic fluoride toxicosis in the small ruminants, sheep and goats in India: focus on its adverse economic consequences. Fluoride. 2022; 55(4):296-310.

59. Choubisa SL. A brief review of fluorosis in dromedary camels (Camelus dromedarius) and focus on their fluoride susceptibility. Austin Journal of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry. 2023;10(1):1-6, id 1117.

60. Choubisa SL. Endemic Hydrofluorosis in Cattle (Bos taurus) in India: An Epitomised Review. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Technology. 2023; 8(1): 1-7.

61. Choubisa SL. Industrial fluoride emissions are dangerous to animal health, but most ranchers are unaware of it. Editorial). Austin Environmental Sciences. 2023;8(1):1-4, id1089.

62. Choubisa SL. A brief review of industrial fluorosis in domesticated bovines in India: focus on its socio-economic impacts on livestock farmers. Journal of Biomed Research. 2023;4(1):8-15.

63. Choubisa SL. Chronic fluoride poisoning in domestic equines, horses (Equus caballus) and donkeys (Equus asinus). Journal of Biomed Research. 2023;4(1):29-32.

64. Choubisa SL. Is drinking groundwater in India safe for domestic animals with respect to fluoride? Archives of Animal Husbandry & Dairy Science. 2023; 2(4):1-7, AAHDS.MS.ID.000544.

65. Choubisa SL. A Brief and Critical Review of Endemic Fluorosis in Domestic Animals of Scheduled Area of Rajasthan, India: Focus on Its Impact on Tribal Economy. Clinical Research in Animal Science. 2023;3(1):1-11, CRAS. 000551.

66. Gupta S, Banerjee S, Mondal S. Phytotoxicity of fluoride in the germination of paddy (Oryza sativa) and its effect on the physiology and biochemistry of germinated seedlings. Fluoride. 2009 Apr 1;42(2):142-6.

67. Mondal D, Gupta S. Influence of fluoride contaminated irrigation water on biochemical constituents of different crops and vegetables with an implication to human risk through diet. Journal of Materials and Environmental Science. 2015;6(11):3134-42.

68. Imran A, Donald S. Accumulation of fluoride in vegetable and associated biochemical changes due to fluoride contamination in water in Western Rajasthan Districts. The Journal of Soil Science and Plant Physiology. 2021;3(2):136.

69. Choubisa SL, Choubisa D. Status of industrial fluoride pollution and its diverse adverse health effects in man and domestic animals in India. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2016 Apr;23(8):7244-54.

70. Choubisa SL, Choubisa D, Choubisa A. Fluoride contamination of groundwater and its threat to health of villagers and their domestic animals and agriculture crops in rural Rajasthan, India. Environmental Geochemistry and Health. 2023 Mar;45(3):607-28.

71. Choubisa SL. Is groundwater irrigation in India safe for the health of agricultural crops with respect to fluoride? AGBIR. 2023, (In-press).

72. Bulusu KR, Nawlakhe WG, Patil AR, Karthikeyan G. In: Bulusu KR, Biswas SK, editors. Prevention and Control of Fluorosis: Water Quality and Defluoridation Techniques. Volume II. New Delhi, India: Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission, Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India, 1993, pp 31-58.