Abstract

Purpose: Patients undergoing Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo HSCT) can develop late complications that limit their functioning and reduce their quality of life. This phase requires nursing-specific knowledge for care plans that can meet the patient’s real needs. For this reason, the purpose of this review is to compile the data available in the literature on late complications present in the follow-up of pediatric and adolescent patients after allo HSCT.

Methods: An integrative review following Cooper’s methodology and the PRISMA guidelines. The search was carried out on PubMed, Scielo, and BIREME. All articles that described long-term complications on pediatric and adolescents allo HCT survivors were included.

Results: Of the 9,783 reviewed publications, 52 met the inclusion criteria. The most frequent long-term complication mentioned was endocrine, followed by pulmonary, cardiovascular, ocular dysfunctions, and secondary neoplasias. Risk factors for late complications after allo HSCT are total body irradiation, chronic graft-versus-host disease, conditioning regimen, gender, donor type, previous therapy, and age at transplant.

Conclusions: With the increased survival, the number of patients living with late complications is growing too. The endocrine complications were the most frequent late complication identified in the studies and can impair quality of life, and demand increasing attention. This knowledge can support develop a tool for assessment and, based on that, creating an individualized care plan focused on the real needs of these patients.

Keywords

Bone marrow transplant, Allogeneic, Late complications, Integrative review

Introduction

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo HCT) has been used to treat malignant and non-malignant hematologic diseases for many years. Despite offering the best chance of survival for many children, it can at the same time lead to long-term complications due to chemotherapy and irradiation used in preparative regimens [1,2].

It was estimated that there will be 502,000 survivors of transplantation by 2030 and 14% of them would be under 18 years of age at the time of transplant [1]. As the number of allo HSCT survivors increases, the late effects and chronic health conditions are more frequent. These indices range from 30 to 60% in patients with an average follow-up of 5 to 15 years, with a progressive increase in risk over time [3]. Chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD) contributed significantly to the increased risk of severe or life-threatening conditions, and more importantly, to the development of multiple chronic conditions [3]. Other risk factors for late effects in HSCT survivors include younger age at HSCT and the use of total body irradiation (TBI) [4].

Transplantation during childhood years can predispose children to late toxicities and consequently, increased morbidity and mortality compared with age and sex-matched counterparts [5].

It is important to note that patients previously treated for malignancy have a cumulative exposure to chemotherapy which may, in turn, account for some of the consequences attributed to the long-term effects of HSCT [6].

Because of the unpredictable, complex, and multifactorial nature of these long-term and late effects in HSCT survivors means that patients require regular life-long assessments guided by rigorous protocols [7]. The care plans can give specific attention to the real needs of the patient at this stage, developing educational actions for the patient and family [7]. Unfortunately, the studies involving the care of post allo HSCT patients are poor, and this knowledge will facilitate the development of appropriate intervention programs to alleviate the long-term effects of HSCT on pediatric quality of life [8].

So, for this reason, the purpose of this integrative review aims to compile the data available in the literature on late complications present in the follow-up of pediatric and adolescents patients after allo HSCT. The following research question guided the search on which the review was based: What are the most frequent late complications in pediatric and adolescent patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation?

Methods

Design

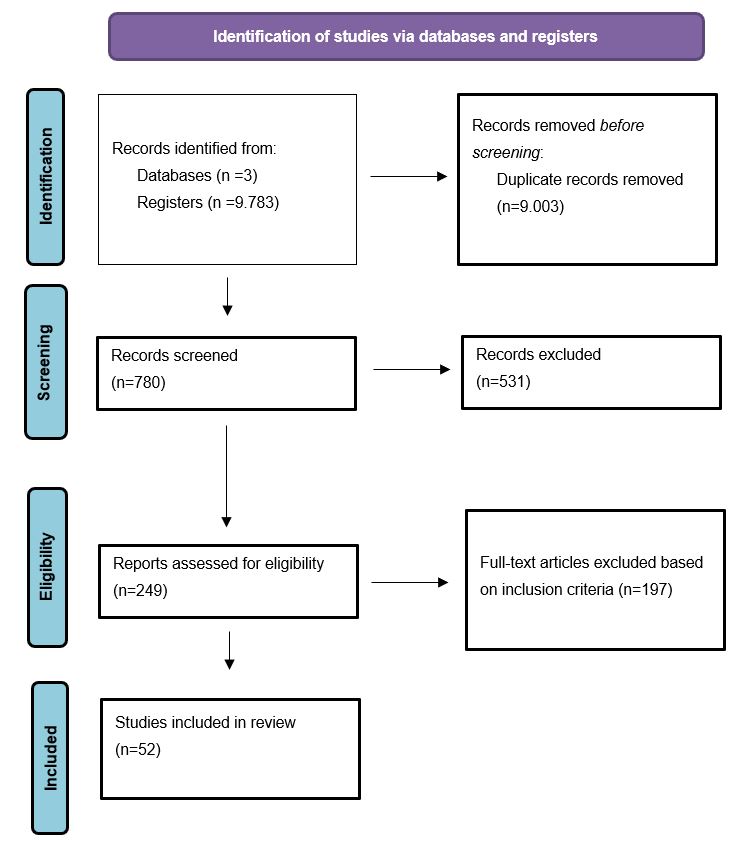

This is an integrative review of the literature adopted the five-step methodology proposed by Cooper [9] and updated by Whittemore [10], which includes: (a) formulation of the problem, (b) literature search, (c) evaluation of data, (d) data analysis and interpretation, and (e) presentation of findings. The integrative review is a type of research review method allowing the simultaneous inclusion of experimental and non-experimental research to, more fully understand a phenomenon of concern [10].This integrative review was informed by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) [11] and the search process is conceptualized in the PRISMA flow diagram [12] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram [11].

Search strategy

For search strategy, it was established a combination of the following MeSH terms and DeCs: “bone marrow cell transplantation”, “hematopoietic stem cell transplantation”, “late effects” and “late complications” with the addition of the Boolean operator “AND”.

The electronic search was made using the following databases: National Library of Medicine (PubMed), Scientific Electronic Library Online (SCIELO), and Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information (BIREME).

Study selection

It was included published research focused on late complications on allo HCT until December 2020, published in English, Spanish or Portuguese; and with free full access. Review articles, dissertations, letters, theses, opinions or perspectives, and commentaries were excluded. Research studies with autologous HCT patients were also excluded.

Analysis

After finding the studies, they were screened by title and abstract. The texts were fully read and analyzed considering the year and place of publication, language, study design, objectives, sample, types of late complications, and outcomes in each identified theme. The duplicate articles were removed and the software program Excel was used to organize and code the articles to facilitate the review. As for ethical aspects, all information extracted from the articles belongs to the public domain.

Results

Study characteristics

The study was conducted from November to December 2020. The first search registered 9,783 articles. After removing duplicate articles and applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 52 articles were included (Figure 1).

All selected articles were written in English. The articles were published between 1990–2020 and most articles were published between 2010 and 2020 (n=34).

The majority of publications is grouped in the United States of America (n=11), followed by Japan (n=7) and The Netherlands (n=6). There is one Brazilian study. Seven publications were multicenter, including data from big data centers such as the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR).

Patients and late complications

In the studies, patient’s age at the time of HSCT ranged from 0.1 to 21 years, and the time after HSCT ranged from 1 to 39 years after HSCT. Both patients who had the malignant disease and those who had non-malignant diseases had late complications.

Figure 2 is the distribution of articles by late complications identified. The most frequent long-term complication mentioned was endocrine, cited in 28 studies, documented from 10 to 91% of the patients in studies. The complications in the endocrine system described in studies are summarized in Table 1.

Figure 2. Distribution of articles by late complications identified.

|

First author, year, and country |

Participants evaluated |

Endocrine Complications |

Risk factors |

|

van Weel-Sipman et al [13], 1990, The Netherlands |

27 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal impairment Growth impairment |

|

|

Hovi et al. [14], 1997, Finland |

15 |

Gonadal/Puberal impairment |

|

|

Hirayama et al. [15], 1998, Japan |

1 |

Diabetes |

|

|

Cohen et al. [16], 1999, Sweden |

79 |

Growth impairment |

|

|

Eapen et al. [17], 2000, USA |

37 |

Growth impairment Thyroid dysfunction |

|

|

Berger et al. [18], 2005, France |

388 |

Thyroid dysfunction |

|

|

Forinder et al. [19], 2005, Sweden |

52 |

Growth impairment |

NA

|

|

Leung et al. [20], 2007, USA |

155 |

Thyroid dysfunction Hypogonadism Growth impairment |

|

|

Ferry et al. [21], 2007, France |

112 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal impairment Growth impairment |

|

|

Löf et al. [22], 2009, Sweden |

53 |

Growth impairment |

NA |

|

Bresters et al. [23], 2010, The Netherlands |

162 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Sanders et al. [24], 2011, USA |

152 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Tomita et al. [25], 2011, Japan |

51 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Hyodo et al. [26], 2012, Japan |

34 |

Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction |

|

|

Mulcahy Levy et al. [27], 2013, USA |

15 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Bresters et al. [28], 2016, EBMT registry |

297 |

Thyroid dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Allewelt et al. [29], 2016, USA |

102 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal l impairmentGrowth impairment |

|

|

Myers et al. [30], 2016, USA |

114 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Madden et al. [31], 2016, USA |

43 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Visentin et al. [32], 2016, France |

314 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Chaudhury et al. [33],2017, USA, Canada, and Unit Arab Emirates |

176 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Vrooman et al. [34], 2017, CIBMTR registry |

717 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Rahal et al. [35], 2018, France |

99 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal impairment Diabetes Growth impairment |

|

|

Faraci et al. [36], 2019, EBMT registry |

137 |

Gonadal/Puberal impairment |

|

|

Sutani et al. [37], 2019, Japan |

23 |

Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction Growth impairment |

|

|

Komori et al. [38], 2019, Japan |

19 |

Gonadal/Puberal dysfunction |

|

|

Marinho et al. [39], 2020, Brazil |

101 |

Thyroid dysfunction Gonadal/Puberal impairment Diabetes Growth impairment |

|

|

Mathiesen et al. [40], 2020, Dinamark and Finland |

98 |

Gonadal/Puberal impairment |

|

|

Abbreviations: NA: Not Available |

|||

The second most frequent is a pulmonary complication, described in 18 studies and the frequency in the population studied ranged from 0 to 81%, following by cardiovascular complication, in 14 studies and frequency ranged from 2 to 26%, ocular and secondary neoplasias, described in 13 studies each, and frequency ranged from 5 to 69% and 2 to 13%, respectively.

Some complications, although frequent in the sample studied, there were a few articles about them, such as psychological e cognitive complications (ranging from 0 to 77% and 9 to 85%, respectively).

Risk factors more related to late complications allo HCT were TBI (described 23 articles) and cGVHD and treatment (described in 11 articles). Other risk factors identified in studies are conditioning regimen, gender, type of donor, previous therapy, and age at transplant.

Discussion

In this review, the analyzed studies showed several late complications after allo HCT in children and young adults. The late complication most found in articles was endocrines. The endocrine system is highly susceptible to damage from high-dose chemotherapy and/or irradiation that is given in the conditioning regimen [41]. The specific endocrine organs most affected by HCT include the thyroid gland, the pituitary, gonads, and hormones that support the development and stability of the skeletal [41]. Our review identified the most frequent complications in thyroid dysfunction, gonadal/puberal impairment, and growth impairment.

Thyroid dysfunction is a commonly encountered problem following HCT and has incidence in pediatric patients undergoing HCT between 0 to 52%, depending upon the size of the cohort and the type of transplants performed [41]. It’s much higher than generally reported for adult patients, where rates are generally around 15% [41]. Thyroid injury has been associated with the use of myeloablative conditioning regimens where radiation is both dose and delivery-dependent [30]. But this complication can occur in patients that use non-myeloablative conditioning too [30].

Another endocrine complication that affects frequently the pediatric population after HCT is growth impairment, with a prevalence of ranges from 20 to 84% [42]. Although pituitary production of growth hormone (GH) plays an important role in determining final height, many other factors play a role, including nutritional status, thyroid function, corticosteroid therapy, and the production of sex hormones during the pubertal growth spurt. The risk of impaired growth is greatest in the youngest children [41,43].

Gonadal impairment and puberty delays are other common endocrine complications in adolescents and young adults after HCT. Puberty, the phase of life when transgression from childhood to a fertile adult occurs, is complex because of the occurring physical changes and the maturational process of the individual [44]. The pre-pubertal status of the child is the result of an active central regulatory process. The changes in body appearance, body composition, and height growth are the consequences of the sex hormones produced [44]. Normal pubertal development requires a functioning hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, and high-dose alkylating agents and/or irradiation to the brain or gonads can disturb can affect this process [44,45].

Both sexes can be affected by pubertal delay or failure. Incomplete pubertal development or pubertal failure has been reported to occur in approximately 57% of prepubescent females following HCT and 53% in males [43]. In males, primary gonadal insufficiency is defined as impaired spermatogenesis, testosterone production, or both [46]. And in females is characterized by primary amenorrhoea (pre-pubertal) or secondary amenorrhoea (for >4 months), elevated FSH, and low estradiol [46]. Premature ovarian insufficiency affects more than 75% of female pediatric HSCT recipients [45]. This complication can affect fertility, and the ability to lead full reproductive lives is very important to both female and male HCT survivors [41].

Despite not being a life-threatening complication, infertility is associated with significant psychological distress for HSCT the recipient and his family [47]. In this review, we identified 8 articles describing infertility as such a late complication. Two of these were aimed at determining fertility status and possible risk factors for infertility [48,49].

Among the risk factors identified in the reviewed articles, TBI was the most cited in late complications, principally in patients with endocrine complications. TBI is an important part of conditioning regimens for bone marrow transplantation for hematological malignancies and can achieve better outcomes than regimens not containing TBI [32]. TBI aims to eradicate malignant cells in the same area that chemotherapy does and in sanctuary organs that are not reached by chemotherapy drugs, which are mainly the brain and testes [32].

Beyond TBI, other risk factors were associated with developing late complications as such alkylants agents in the preparative regimen, act at HCT, steroid therapy, and sex [5,43].

Although the treatment before HSCT in patients with the malignant disease was a risk factor, we can note in the studies that patients with malignant disease and those non-malignant diseases can be affected with late complications, and both need attention on late follow-up after HSCT [32]. Patients who do TBI needs more attention, mainly endocrine complications.

It has been identified some complications that, although they have a high incidence in patients after HSCT, few articles describe them, such as psychological e cognitive complications that may not directly impact mortality, but can impair quality of life. Psychological complications include, among others, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and neurocognitive deficits. Depression occurs in 12%-30% of HCT survivors and is more frequent in female patients, younger patients, and those with poor social support, history of recurrent disease, chronic pain, and chronic GvHD [50]. Post-traumatic stress disorder occurs in 28% of patients at six months after HCT and may persist for 5%-13% of cases, although its risk factors are not yet clear [50].

Pediatric patients may experience altered behavior patterns, changes in social habits, and changes in academic/school behavior years after HSCT. At the transition from acute convalescence to long-term follow-up, psychological distress may increase rather than abate as the patient and his/her family must cope with changes in roles, employment situations, and financial difficulties [43].

The limitation of this review is the selection of English, Portuguese and Spanish language studies; which may contribute to the exclusion of relevant studies published in other languages.

Conclusions

The endocrine complications were the most frequent late complication identified in the studies and can impair quality of life. It is necessary to consider more studies with complications like cognitive and psychological because these can impair quality of life too. This knowledge can support nursing practices in late follow-up HSCT. Nurses can develop a tool for assessment and, based on that, develop an individualized care plan focused on the real needs of these patients.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The Authors declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

2. Martin PJ, Counts GW, Jr Appelbaum FR, Lee SJ, Sanders JE, Deeg HJ, et al. Life expectancy in patients surviving more than 5 years after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2010;28(6):1011-1016.

3. Sun CL, Francisco L, Kawashima T, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Baker KS, et al. Prevalence and predictors of chronic health conditions after hematopoietic cell transplantation: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 2010;116(17):3129-3377.

4. Hierlmeier, S, Eyrich M, Wölfl M, Schlegel PG, Wiegering V. Early and late complications following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in pediatric patients - A retrospective analysis over 11 years. PloS One. 2018;13(10): e0204914.

5. Dietz AC, Duncan CN, Alter BP, Bresters D, Cowan MJ, Notarangelo L, et al. The Second Pediatric Blood and Marrow Transplant Consortium International Consensus Conference on Late Effects after Pediatric Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Defining the Unique Late Effects of Children Undergoing Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Immune Deficiencies, Inherited Marrow Failure Disorders, and Hemoglobinopathies. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2017;23(1):24-29.

6. Syrjala KL, Martin PJ, Lee SJ. Delivering care to long-term adult survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;30 (30):3746-3751.

7. Kenyon M, Babic A. The European Blood and Marrow Transplantation Textbook for Nurses: Under the Auspices of EBMT [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer;2018. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK543668/

8. Tanzi EM. Health-Related Quality of Life of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Childhood Survivors. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2011;28:191–202.

9. Cooper HM. Scientific Guidelines for Conducting Integrative Research Reviews. Review of Educational Research. 1982;52(2):291-302.

10. Whittemore R, Knafl K. The integrative review: updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;52(5):546-553.

11. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372(71).

12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

13. van Weel-Sipman MH, van't Veer-Korthof ET, van den Berg H, Gerritsen EJ, Noordijk EM, Kamphuis RP, et al. Late effects of total body irradiation and cytostatic preparative regimen for bone marrow transplantation in children with hematological malignancies. Radiotherapy and Oncology: Journal of the European Society for Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology. 1990;18 Suppl 1:155-157.

14. Hovi L, Tapanainen P, Saarinen-Pihkala U. Impaired androgen production in female adolescents and young adults after total body irradiation prior to BMT in childhood. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997;20:561-565.

15. Hirayama M, Azuma E, Kumamoto T, Qi J, Kobayashi M, Komada Y, et al. Late-onset unilateral renal dysfunction combined with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and bronchial asthma following allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a child. Bone Marrow Transplantion. 1998;22(9):923-926.

16. Cohen A, Duell T, Socié G, van Lint MT, Weiss M, Tichelli A, et al. Nutritional status and growth after bone marrow transplantation (BMT) during childhood:EBMT Late-Effects Working Party retrospective data. European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1999;23(10):1043–1047.

17. Eapen M, Ramsay NK, Mertens AC, Robison LL, DeFor T, Davies SM. Late outcomes after bone marrow transplant for aplastic anaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2000;111(3):754-760.

18. Berger C, Le-Gallo B, Donadieu J, Richard O, Devergie A, Galambrun C, et al. Late thyroid toxicity in 153 long-term survivors of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;35(10):991-995.

19. Forinder U, Löf C, Winiarski J. Quality of life and health in children following allogeneic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;36(2):171–176.

20. Leung W, Ahn H, Rose SR, Phipps S, Smith T, Gan K, et al. A prospective cohort study of late sequelae of pediatric allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Medicine. 2007;86(4):215-224.

21. Ferry C, Gemayel G, Rocha V, Labopin M, Esperou H, Robin M, et al. Long-term outcomes after allogeneic stem cell transplantation for children with hematological malignancies. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2007;40(3):219-224.

22. Löf CM, Winiarski J, Giesecke A, Ljungman P, Forinder U. Health-related quality of life in adult survivors after paediatric allo-SCT. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2009;43(6):461–468.

23. Bresters D, van Gils IC, Kollen WJ, Ball LM, Oostdijk W, van der Bom JG, et al. High burden of late effects after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood: a single-center study. Bone Marrow Transplantation.2010;45 (1):79-85.

24. Sanders JE, Woolfrey AE, Carpenter PA, Storer BE, Hoffmeister PA, Deeg HJ, et al. Late effects among pediatric patients followed for nearly 4 decades after transplantation for severe aplastic anemia. Blood. 2011;118(5):1421-1428.

25. Tomita Y, Ishiguro H, Yasuda Y, Hyodo H, Koike T, Shimizu T, et al. High incidence of fatty liver and insulin resistance in long-term adult survivors of childhood SCT. Bone marrow transplantation. 2011;46(3):416-425.

26. Hyodo H, Ishiguro H, Tomita Y, Takakura H, Koike T, Shimizu T, et al. Decreased serum testosterone levels in long-term adult survivors with fatty liver after childhood stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18(7):1119-1127.

27. Mulcahy Levy JM, Tello T, Giller R, Wilkening G, Quinones R, Keating AK, et al. Late effects of total body irradiation and hematopoietic stem cell transplant in children under 3 years of age. Pediatric Blood & Cancer.2013;60(4):700-704.

28. Bresters D, Lawitschka A, Cugno C, Pötschger U, Dalissier A, Michel G, et al. Incidence and severity of crucial late effects after allogeneic HSCT for malignancy under the age of 3 years:TBI is what really matters. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2016;51(11):1482–1489.

29. Allewelt H, El-Khorazaty J, Mendizabal A, Taskindoust M, Martin PL, Prasad V, et al. Late Effects after Umbilical Cord Blood Transplantation in Very Young Children after Busulfan-Based, Myeloablative Conditioning. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation:journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22 (9):1627-1635.

30. Myers KC, Howell JC, Wallace G, Dandoy C, El-Bietar J, Lane A, et al. Poor growth, thyroid dysfunction and vitamin D deficiency remain prevalent despite reduced intensity chemotherapy for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children and young adults. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2016;51(7):980-984.

31. Madden LM, Hayashi RJ, Chan KW, Pulsipher MA, Douglas D, Hale GA, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up after Reduced-Intensity Conditioning and Stem Cell Transplantation for Childhood Nonmalignant Disorders. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(8):1467-1472.

32. Visentin S, Auquier P, Bertrand Y, Baruchel A, Tabone MD, Pochon C, et al. The Impact of Donor Type on Long-Term Health Status and Quality of Life after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Childhood Acute Leukemia:A Leucémie de l'Enfant et de L'Adolescent Study. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2016;22(11):2003–2010.

33. Chaudhury S, Ayas M, Rosen C, Ma M, Viqaruddin M, Parikh S, et al. A Multicenter Retrospective Analysis Stressing the Importance of Long-Term Follow-Up after Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for β-Thalassemia. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2017;23(10):1695–1700.

34. Vrooman LM, Millard HR, Brazauskas R, Majhail NS, Battiwalla M, Flowers M, et al. Survival and Late Effects after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancy at Less than Three Years of Age. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2017;23(8):1327-1334.

35. Rahal I, Galambrun C, Bertrand Y, Garnier N, Paillard C, Frange P, et al. Late effects after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for β-thalassemia major: the French national experience. Haematologica. 2018;103(7):1143–1149.

36. Faraci M, Diesch T, Labopin M, Dalissier A, Lankester A, Gennery A, et al. Gonadal Function after Busulfan Compared with Treosulfan in Children and Adolescents Undergoing Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2019;25(9):1786–1791.

37. Sutani A, Miyakawa Y, Tsuji-Hosokawa A, Nomura R, Nakagawa R, Nakajima K, et al. Gonadal failure among female patients after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for non-malignant diseases. Clinical Pediatric Endocrinology: Case Reports and Clinical Investigations: Official Journal of the Japanese Society for Pediatric Endocrinology. 2019;28(4):105–112.

38. Komori K, Hirabayashi K, Morita D, Hara Y, Kurata T, Saito S, et al. Ovarian function after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children and young adults given 8-Gy total body irradiation-based reduced-toxicity myeloablative conditioning. Pediatric Transplantation. 2019;23:e13372.

39. Marinho DH, Ribeiro LL, Nichele S, Loth G, Koliski A, Mousquer RTG, et al. The challenge of long-term follow-up of survivors of childhood acute leukemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in resource-limited countries:A single-center report from Brazil. Pediatric Transplantation. 2020;24:e13691.

40. Mathiesen S, Sørensen K, Nielsen MM, Suominen A, Ifversen M, Grell K, et al. Male Gonadal Function after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Childhood:A Cross-Sectional, Population-Based Study. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2020;26(9):1635–1645.

41. Dvorak CC, Gracia CR, Sanders JE, Cheng EY, Baker KS, Pulsipher MA, et al. NCI, NHLBI/PBMTC first international conference on late effects after pediatric hematopoietic cell transplantation: endocrine challenges-thyroid dysfunction, growth impairment, bone health, & reproductive risks. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17(12):1725–1738.

42. Paetow U, Bader P, Chemaitilly W. A systematic approach to the endocrine care of survivors of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2020;39(1):69-78.

43. Majhail NS, Rizzo JD, Lee SJ, Aljurf M, Atsuta Y, Bonfim C, et al. Recommended screening and preventive practices for long-term survivors after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2012;47(3):337–341.

44. Ranke MB, Schwarze CP, Dopfer R, Klingebiel T, Scheel-Walter HG, Lang P, et al. Late effects after stem cell transplantation (SCT) in children – growth and hormones. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2005;35(S1):S77–S81.

45. Shalitin S, Pertman L, Yackobovitch-Gavan M, Yaniv I, Lebenthal Y, Phillip M,et al. Endocrine and Metabolic Disturbances in Survivors of Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Childhood and Adolescence. Hormone Research in Paediatrics. 2018;89(2):108–121.

46. Gunn HM, Rinne I, Emilsson H, Gabriel M, Maguire AM, Steinbeck KS. Primary Gonadal Insufficiency in Male and Female Childhood Cancer Survivors in a Long-Term Follow-Up Clinic. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology.2016;5(4):344–350.

47. Tichelli A, Rovó A. Fertility issues following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Expert Review of Hematology. 2013;6(4):375–388.

48. Borgmann-Staudt A, Rendtorff R, Reinmuth S, Hohmann C, Keil T, Schuster FR, et al. Fertility after allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation in childhood and adolescence. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2012;47(2):271–276.

49. Haavisto A, Mathiesen S, Suominen A, Lähteenmäki P, Sørensen K, Ifversen M, et al. Male Sexual Function after Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Childhood: A Multicenter Study. Cancers. 2020;12(7):1786.

50. Inamoto Y, Lee SJ. Late effects of blood and marrow transplantation. Haematologica. 2017;102(4):614–625.