Abstract

Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) is a systemic, chronic, inflammatory and erosive joint disease. Due the systemic effect mediated by increased serum pro-inflammatory cytokines, RA patients often present changes in body composition. Sarcopenia, obesity, and rheumatoid cachexia (sarcopenic obesity) are often observed in RA patients. On other hand, classical cachexia in RA is rarely observed. All these conditions are associated with increased healthcare costs, functional disability, poorer quality of life and increased mortality. During the last 2 decades several disease modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) have been used to minimize disease activity and delay joint destruction, markedly improving outcomes. However, the impact of these drugs on the altered body composition has not been adequately studied. While glucocorticoid has well known negative impact on muscle mass, limited data indicate that tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors seem to be more associated with increased fat mass and tocilizumab, an interleukin-6 (IL-6) inhibitor might increase lean mass. However, the observed effects seem to be limited, stressing the importance of additional effective measures, such as regular strength exercises and adequate nutrition.

Keywords

Rheumatoid Arthritis, Body Composition, Sarcopenia, Cachexia, Pharmacological Treatment

Abbreviations

ALMIFMI: Adjusting the muscle mass for fat mass; bDMARD: The biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs; FM: Fat Mass; IRS-1:The inhibition of the Insulin Receptor Substrate-1; MTX: Methotrexate; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; sDMARD: The synthetic drugs modifying the course of the disease; WHO: World Health Organization.

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, progressive, inflammatory autoimmune disease characterized by symmetrical, destructive polyarthritis accompanied by systemic manifestations [1,2]. Excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines plays a major role in the pathophysiology of RA [3]. In addition, metabolic changes as increased energy expenditure and increased protein degradation, induced by proinflammatory cytokines, are observed in RA patients [3-5]. So, due to systemic catabolic activities, the proinflammatory cytokines may play a major role in body composition changes. TNF-α and IL-1β present similar catabolic actions on muscle mass [6]. In addition, it is known that IL-6 [7,8] might have diverse impacts, including anabolic and catabolic effects, affecting directly muscle mass and fat mass alterations seen in RA patients. This altered metabolism may lead to changes in body composition.

Several terms have been used to describe changes in body composition in RA patients, including sarcopenia, sarcopenic obesity, rheumatoid cachexia and classical cachexia [9,10]. According to Cruz-Jentoff, sarcopenia is considered a muscle disease (muscle failure) where the individuals have decreased muscle strength associated with low muscle quantity and quality [10]. Obesity is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as abnormal or excessive fat mass that presents a risk to health [11]. Yet, sarcopenic obesity is a condition of reduced skeletal muscle mass in the context of excess adiposity [10]. Rheumatoid cachexia is a term that has been used to describe the condition of reduced fat-free mass (FFM), of which muscle mass is the major component, with or without loss of fat mass (FM), resulting in no or limited changes in body mass index [12,13]. Classic cachexia is characterized by severe loss of weight, fat, and muscle mass and increased protein catabolism due to underlying disease(s) [14].

Often sarcopenic obesity and rheumatoid cachexia are observed in RA patients, whereas classic cachexia is infrequently observed. Recent studies demonstrated a prevalence of sarcopenia of 17.1%-37.1% in RA patients [15,16]. On other hand, a systematic review with meta-analysis indicates that the estimated prevalence of rheumatoid cachexia ranges from 19% to 32% [9]. The explanation for the variability in the prevalence rates is probably related to use of different diagnostic criteria, since there is no consensus in the literature regarding the appropriate body composition parameters for each condition, as well as the definitions of conditions is diverse in the available literature [9].

Regarding to the methods of assessment of body composition the computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA), bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and anthropometric methods are used [17,18]. Additionally, alternative or new tests and tools have been suggested, such as computed tomography (mid-thigh muscle measurement, psoas muscle measurement at 3rd lumbar vertebra level), creatine dilution test, ultrasound assessment of muscle and specific biomarkers or panels of biomarkers [10]. However, most of these modalities have high cost that makes their use unfeasible in population studies and difficulty of use in routine clinical contexts.

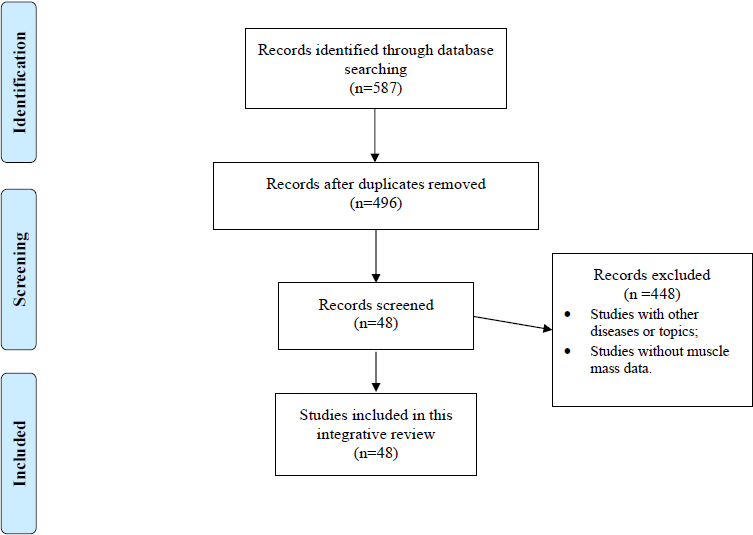

These changes in body composition may result in increased healthcare costs, functional disability, poorer quality of life and increased mortality in RA patients [19,20]. Therefore, in this integrative review, our objective was to present an overview of the impact of pharmacological treatments used in RA on body composition, with a focus on muscle mass. An electronic search was performed using MEDLINE (via PubMed) and other relevant sources. Keywords and medical subject headings for the terms ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ OR ‘arthritis’, OR ‘arthritis rheumatoid’ AND ‘body composition’ AND ‘muscle mass’, AND ‘glucocorticoids’ AND ‘conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs' AND ‘biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs’ were selected. Randomized controlled trials or non-randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, reviews and experimental models were included. Studies with other diseases or topics or studies without muscle mass data were excluded. The flowchart of this integrative review is in (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The flowchart of this integrative review.

Changes of body Composition in RA Patients

Recent studies have shown the prevalence of sarcopenia and rheumatoid cachexia in RA patients, as well as, the risk factors to these conditions. In a meta-analysis [21], the authors have demonstrated a prevalence of sarcopenia of 35% in RA patients, among which the prevalence in male and female were 39.8% and 33.3% respectively. In addition, they reported various factors significantly associated with sarcopenia in subjects with RA, such as age, female gender, CRP, HAQ and RF seropositivity [21]. On other hand, we have reported that rheumatoid cachexia was quite prevalent (13.3–30.0%) in a cohort of patients with established RA, but no classic cachexia was identified [22]. In addition, rheumatoid cachexia and other factors related with cachexia, especially physical function, may be influenced by disease status [22].

Regarding to muscle mass, studies have reported that even RA patients receiving adequate intensive treatment have ∼10% proportionally less appendicular lean mass compared to healthy controls [23,24]. After adjusting the muscle mass for fat mass (ALMIFMI), RA patients were shown to have lower ALMIFMI and lower muscle density, a composite index of intramuscular fat substitution, compared to a healthy nationally representative sample [25,26]. When analyzing the muscle architecture of the RA patients, Blum et al. [27] demonstrated that RA patients had smaller muscle thickness (-23.3%) and pennation angle, the angulation of muscle fibers relative to the line of action of muscle in pennate muscles (-14.1%), compared with healthy women. On other hand, no differences were observed in muscle activation of quadriceps assessed by electromyography during an isometric test and fascicle length (the distance between the intersection composed of the superficial aponeurosis and fascicle and the intersection composed of the deep aponeurosis and the fascicle) [27].

Regarding to adiposity, RA patients had more redistribution of fat mass to the trunk than healthy persons [24,28], and RA with moderate/high disease activity showed more fat mass index (FMI) than RA with low disease activity [22]. In addition, women with RA had a 4% higher mean fat mass index (FMI) when compared to females without RA [28]. Analyzing intramuscular fat and intermuscular adipose tissue, Khoja et al. [29] have demonstrated that skeletal muscle fat accumulation in RA was higher than in healthy individuals. In addition, the accumulation of fat within and around the muscles in RA is similar to that of healthy older individuals, indicating early tissue senescence [29].

Influence of Pharmacological Treatments on Body Composition in RA patients

Glucocorticoids (GC) are used to treat many patients for a variety of conditions and are arguably the most important, and most frequently used, class of immunosuppressive drug worldwide [30]. In RA, GC have not only potent anti-inflammatory properties but are also disease-modifying, with a beneficial impact on radiological progression [31], and have been recommended as short-term initial treatment or bridging therapy when initiating or changing other antirheumatic drugs [32].

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are drugs that have been shown to improve disease activity and prevent the typical joint damage of rheumatoid arthritis. They are now classified as conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs, that comprehend mainly methotrexate, but also leflunomide, sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine [1], and the more recent biological (b)DMARDs and targeted synthetic (ts)DMARDs. The first line of the pharmacological treatment used by rheumatologists is the (cs)DMARDs, with bDMARDs and tsDMARDs being reserved to the second line when the therapeutic response is insufficient with one or more of these drugs. bDMARDs include monoclonal antibodies or receptor constructs targeting proinflammatory cytokines, such as TNF (infliximab, etanercept, adalimumab, certolizumabe and golimumab) and IL-6 (tocilizumab and sarilumab). Current tsDMARDs include inhibitors of Janus tyrosine kinase (JAK) inhibitors, fundamental for the intracellular signaling of type I and II cytokines (tofacitinib, baricitinib and upadacitinib) [1]. Concomitant these pharmacological treatments, glucocorticoids are used in therapeutic management in RA patients[33]. Despite the use of glucocorticoids, sDMARDs and bDMARDs to control inflammation and joint damage, the effect of these drugs on RA associated skeletal muscle wasting and altered body composition remains insufficiently studied, as described below.

Glucocorticoid

Analyzing the corticosteroid use, Lemmey et al. [34] described that a 120 mg intramuscular (IM) corticosteroid (CS) injection develops substantial muscle loss after 4 weeks of the single injection. Corroborating with Lemmey et al. [34], Yamada et al. [35] demonstrated that RA patients using GCs at an average dose ≥ 3.25 mg/day over 1 year were at higher risk for developing sarcopenia. Yang et al. [36] demonstrated in 620 RA patients that RA patients with previous glucocorticoid (GC) therapy showed lower fat-free mass and lower muscle indicators including appendicular muscle mass especially in both lower extremities when compared with those with previous DMARDs therapy only. In the same direction Yamada et al. [37] found that GC use was associated with deterioration in muscle quality and function, as well as sarcopenia development.

csDMARDs

Synthetic DMARDs are the first choice to control RA activity [32,33]. These drugs act by blocking critical pathways in RA physiopathology such as folate synthesis (MTX), signaling of inflammatory cytokines such IL-2 and IL-6 (leflunomide) and activation of inflammatory transcription factor NF-κB (sulfasalazine). However, their effect on skeletal muscle is still unclear. Some studies provide evidence to support that these drugs may have some impact.

Methotrexate: The usual first choice in RA treatment, methotrexate (MTX) might have some potential beneficial effect on skeletal muscle, based on very few studies. A study with myoblast cell culture indicates a positive effect of MTX on muscle energy metabolism by an indirect activation of AMPk in myotubes that leads to lipid oxidation and induction of glucose uptake [38]. MTX treatment was able to significantly reduce the mass loss of the tibialis anterior, the exterior digitorum longus and gastrocnemius muscles in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis [39]. In humans [40], twenty-six patients were randomly assigned to 24 weeks of treatment with etanercept (n=12) or methotrexate (n=14). At baseline, the etanercept group showed 41.3 ± 9.7 kg of lean mass, while that methotrexate group showed 41.2 ± 8.5 kg of lean mass. Regarding fat mass, the etanercept group showed 31.7 ± 8.2 kg of fat mass, while that methotrexate group showed 28.9 ± 13.8 kg of lean mass. There is no significant statistical difference between groups. After 24 weeks of treatment, there is no significant statistical difference between groups to lean mass and fat mass. Of these patients that gained >3% of their baseline body mass over the 24 weeks follow-up period (6/treatment group) the patients in the etanercept group gained a significantly (p=0.04) greater proportion of fat free mass than did the patients in the methotrexate group, while that no difference on fat mass was observed [40].

Leflunomide: As MTX, leflunomide is widely used in management of inflammatory joint disease. Besides its utilization to control disease activity, there is evidence to support that this drug also has an effect on muscle tissue. In a murine model of myasthenia gravis, an autoimmune disease that impairs muscular function, leflunomide was able to block disease development and improve muscular frailty caused by disease. These results were obtained, according to authors, by inhibition of inflammatory cytokines IL-2 and IL-6 [41]. In the same study, was evaluated the effect of leflunomide metabolite A77 1726 on L6 myotubes cells. The metabolite was able to increase glucose uptake in those cells in culture. Based on this, leflunomide might also have a positive effect on insulin metabolism improving energetic pathways of muscle cells [41]. Besides, there are no studies evaluating the effect of leflunomide on skeletal muscle in RA patients.

Sulphasalazine and Hydroxychloroquine: Sulphasalazine is also widely used in management of inflammatory arthropathies, although its use in RA is decreasing lately. It has been shown, in a Duchenne dystrophy model, that sulfasalazine acts impairing survival in developing myotubes. This effect is credited to signaling reduction of NF-κB and subsequent decreased expression of intracellular p65 protein [42]. There are no clinical studies evaluating the effect of isolated sulphasalazine or hydroxychloroquine. However, Engvall et al. [43] compared the addition of sulfasalazine and hydroxychloroquine to the addition of infliximab in 40 patients with early RA that had failed MTX treatment. Approximately 20% had low muscle mass at baseline. Despite similar reduction in disease activity, patients on triple therapy had stable muscle mass from months 3 to 24 and less increase in fat mass compared to infliximab treatment. Therefore, control of disease activity was not associated with increase in muscle mass in both groups.

bDMARDs

Few studies have evaluated the effects of the bDMARDS on body composition in RA patients. In an observational cohort of established RA patients, we have recently demonstrated that bDMARDs treatment in general was not associated with significant effects on body composition after 12 months [22]. However, it is possible that bDMARD with different targets might present distinct impacts on muscle mass [22].

Regarding the effects on physical function (PF) and falls, Hirano et al. [44] recently demonstrated that there is improvement in PF, muscle power and agility after 3–6 months, and risk of falls decrease after 12 months after the initiation of bDMARD treatment [44].

TNF inhibitors: TNF inhibitors are very effective drugs for inflammatory joint diseases. However, their action on skeletal muscle has not been consistently demonstrated. In a rat model subjected to physical exercise, infliximab was able to reduce the expression of inflammatory cytokines in muscle samples from these animals. Also, it was observed an increased expression of regeneration markers M-caderin and myf-6, when rats were treated with infliximab [45]. Another study demonstrated that the anti-TNF agent PEG-sTNFRI did not prevent the increase in muscle gene expression of E3 ubiquitin-ligating enzymes, MuRF1 and MAFbx, associated with myofiber degeneration, in arthritic rats [46].

In humans, anti-TNF therapy has been associated with weight gain and increase in fat mass, while the impact on lean mass seems to be very limited. In a small randomized trial comparing etanercept and methotrexate in RA patients, no difference in body composition was observed after 24 weeks [40]. However, when evaluating only the patients that presented an increase >3% in body weight during follow-up (~50%), a significant difference was found: 44% of the gained weight in the etanercept group was fat-free mass, while it was only 14% in the methotrexate group [40]. In a bigger trial, infliximab added to MTX-inadequate responders induced an increase in fat mass compared to triple therapy, without increase in lean mass [43]. Toussirot et al. [47] observed gain in fat mass and no changes in lean mass after 2 years of the treatment with TNFα inhibitors in 8 RA patients. Serelis et al. [48] demonstrated that anti-TNF treatment (12 infliximab and 7 adalimumab) in women with RA does not have any significant effect on body composition after one year of treatment. Metsios et al. [49] showed that after 12 weeks of anti-TNF-alpha therapy in 20 RA patients, no change in body composition was observed. These studies are described in (Table 1).

|

Reference |

Type of study |

N |

Age mean |

Disease |

Study duration |

Drug used |

Results |

|

Domínguez-Álvarez et al. [45] |

Animal model |

48 |

- |

Induction of exercise |

2 weeks |

Infliximab |

Reduction in muscle inflammatory cytokine expression. Increase of muscle regeneration markers. |

|

Granado et al. [46] |

Animal model |

44 |

- |

Arthritis |

37 days |

PEG-sTNFRI |

Did not prevent expression of muscle degradation genes. |

|

Marcora et al. [40] |

Clinical Trial |

26 |

54 |

RA |

24 weeks |

Etanercept |

Among patients with body composition changes, those who are given etanercept gained majoritary free-fat mass. |

|

Toussirot et al. [47] |

Clinical Trial |

20 |

48,6 |

RA |

2 years |

Inflixumab, adalimumab, etanercept |

Increased fat mass with no changes in lean mass. |

|

Serelis et al. [48] |

Clinical Trial |

19 |

54 |

RA |

1 year |

Inflixumab, adalimumab |

No changes in muscle mass. |

|

Metsios et al. [49] |

Clinical Trial |

20 |

61,1 |

RA |

12 weeks |

ND |

No changes in muscle mass. |

IL-6 inhibitors: IL-6 inhibitors are designed drugs to bind specifically to the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 or its receptor and block subsequent inflammatory signaling [50]. As TNF inhibitors, treatment with tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6-R monoclonal antibody, has been associated with weight gain [51]. On the other hand, two studies have suggested that it can have an anabolic effect on skeletal muscle. Tournadre et al. [52] demonstrated that after one year of treatment with tocilizumab in a cohort of 21 RA patients there was an increase in weight, significant gain in fat-free mass and appendicular lean mass, with no changes in fat composition. Corroborating these observations, a recent study has shown that RA patients treated with tocilizumab had significant gain of lean mass, while fat mass (total fat or abdominal fat) did not change [53]. These studies suggest that IL-6 targeted therapy may have a therapeutic effect on sarcopenia in RA patients, although larger controlled trials are needed to confirm these observations.

JAK inhibitors (JAKi): The inhibition JAK tyrosine-kinases can lead to a blockade of intracellular signaling of a large number of cytokines, many of those involved in the pathophysiology of RA, such as the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IFN-γ [54]. JAKi treatment promotes reduced T Cell and other leukocytes recruitment, consequently, synovial inflammation and articular damage in RA patients [55,56]. JAKi treatment appears to induce some weight gain. Novikova et al. followed 31 patients with RA using tofacitinib for 1 year and observed a 4.2% increase in weight [57]. However, these patients appear to have a decrease in visceral fat. Concerning skeletal muscle, JAKi have been associated with increased serum levels of creatine phosphokinase (CPK) in patients with RA and other inflammatory arthropathies, without any evidence of muscle damage on histological evaluations or clinical symptoms of myalgia or weakness [58]. A recent study has proposed that this could be the result of inhibition of the cytokine oncostatin M, which can block myoblast differentiation. In fact, upadacitinib treated collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) rats exhibited enhanced serum CPK and were protected from muscle fiber area loss, suggestive of a potential positive effect on arthritis associated sarcopenia [59]. The only report in patients is a small study with 4 patients with bDMARDs (anti-TNF and anti-IL-6R) and 4 patients with tofacitinib, there was no changes in body composition measured by bioelectric impedance in the bDMARDs, while tofacitinib increased body fat mass [60].

Inhibitors of costimulatory molecules: There is no data from the relation of costimulation blocking drugs abatacept and rituximab with muscular tissue and its aspects in rheumatic diseases.

Conclusion

In conclusion, a large proportion of RA patients present significant skeletal muscle wasting associated with preserved or increased fat mass, which has been attributed to the catabolic effects of proinflammatory cytokines and associated with impaired function. Although the use of DMARDs, particularly the targeted bDMARDs and stDMARDs, has been demonstrated to be very effective in controlling joint and systemic inflammation, their effect on sarcopenia remains unclear. TNF inhibitors appear to increase fat mass with minor changes in lean mass, while tocilizumab, an anti-IL6R, may have some positive effect by increasing muscle mass, while very little or no data is available for other DMARDs. Clearly more studies are needed to have a better picture of the impact of these drugs on rheumatoid sarcopenia. However, it can be argued that controlling inflammation can prevent additional muscle wasting, but it is not enough to recover the lost muscle mass. Therefore, additional strategies for the management of sarcopenia, such as the combination of adequate nutrition and strength exercises, are crucial to maximize function in these patients.

Funding

Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre; Recipient: Ricardo Machado Xavier.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declared no conflict of interest.

Author Contributions Statement

All authors were responsible for writing this article.

References

2. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016 Oct 22;388(10055):2023-2038.

3. McInnes IB, Schett G. The pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011 Dec 8;365(23):2205-19.

4. Walsmith J, Abad L, Kehayias J, Roubenoff R. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha production is associated with less body cell mass in women with rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2004 Jan 1;31(1):23-9.

5. Roubenoff R, Roubenoff RA, Ward LM, Holland SM, Hellmann DB. Rheumatoid cachexia: depletion of lean body mass in rheumatoid arthritis. Possible association with tumor necrosis factor. The Journal of Rheumatology. 1992 Oct;19(10):1505-10.

6. Roubenoff R, Rall LC. Humoral mediation of changing body composition during aging and chronic inflammation. Nutrition Reviews. 1993 Jan 1;51(1):1-1.

7. Muñoz‐Cánoves P, Scheele C, Pedersen BK, Serrano AL. Interleukin‐6 myokine signaling in skeletal muscle: a double‐edged sword?. The FEBS Journal. 2013 Sep 1;280(17):4131-48.

8. Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscle as an endocrine organ: focus on muscle-derived interleukin-6. Physiological Reviews. 2008 Oct 1.

9. Santo RC, Fernandes KZ, Lora PS, Filippin LI, Xavier RM. Prevalence of rheumatoid cachexia in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 2018 Oct;9(5):816-25.

10. Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and Ageing. 2019 Jan 1;48(1):16-31.

11. World Health Organization (WHO). Key Facts—Obesity and Overweight. 2020.

12. Engvall IL, Elkan AC, Tengstrand B, Cederholm T, Brismar K, Hafström I. Cachexia in rheumatoid arthritis is associated with inflammatory activity, physical disability, and low bioavailable insulin‐like growth factor. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2008 Jan 1;37(5):321-8.

13. Elkan AC, Engvall IL, Cederholm T, Hafström I. Rheumatoid cachexia, central obesity and malnutrition in patients with low-active rheumatoid arthritis: feasibility of anthropometry, Mini Nutritional Assessment and body composition techniques. European Journal of Nutrition. 2009 Aug 1;48(5):315-22.

14. Evans WJ, Morley JE, Argilés J, Bales C, Baracos V, Guttridge D, et al. Cachexia: a new definition. Clinical Nutrition. 2008 Dec 1;27(6):793-9.

15. Torii M, Hashimoto M, Hanai A, Fujii T, Furu M, Ito H, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Modern Rheumatology. 2019 Jul 4;29(4):589-95.

16. Vlietstra L, Stebbings S, Meredith-Jones K, Abbott JH, Treharne GJ, Waters DL. Sarcopenia in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: The association with self-reported fatigue, physical function and obesity. PloS One. 2019 Jun 6;14(6):e0217462.

17. Beaudart C, McCloskey E, Bruyère O, Cesari M, Rolland Y, Rizzoli R, et al. Sarcopenia in daily practice: assessment and management. BMC Geriatrics. 2016 Dec 1;16(1):170.

18. Treviño-Aguirre E, López-Teros T, Gutiérrez-Robledo L, Vandewoude M, Pérez-Zepeda M. Availability and use of dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) and bio-impedance analysis (BIA) for the evaluation of sarcopenia by Belgian and Latin American geriatricians. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 2014 Mar 1;5(1):79-81.

19. Lemmey AB. Rheumatoid cachexia: the undiagnosed, untreated key to restoring physical function in rheumatoid arthritis patients? Rheumatology. 2016. 55(7): 1149–1150.

20. Lemmey AB, Jones J, Maddison PJ. Rheumatoid cachexia: what is it and why is it important?. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2011 Sep 1;38(9):2074-.

21. Li TH, Chuang CC, Chang YS, Lai CC, Su CF, Liu CW, et al. A meta-analysis for the prevalence and risk factors of sarcopenia in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2020 Jun 1;79(Suppl 1):286.

22. Santo RC, Silva J, Lora PS, Moro AL, Freitas EC, Bartikoski BJ, et al. Cachexia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a cohort study. Clinical Rheumatology. 2020 May 23.

23. Lemmey AB, Wilkinson TJ, Clayton RJ, Sheikh F, Whale J, Jones HS, et al. Tight control of disease activity fails to improve body composition or physical function in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology. 2016 Oct 1;55(10):1736-45.

24. Reina D, Gómez-Vaquero C, Díaz-Torné C, Solé JM. Assessment of nutritional status by dual X-Ray absorptiometry in women with rheumatoid arthritis: A case–control study. Medicine. 2019 Feb;98(6).

25. England BR, Baker JF, Sayles H, Michaud K, Caplan L, Davis LA, et al. Body mass index, weight loss, and cause‐specific mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2018 Jan;70(1):11-8.

26. Baker JF, Long J, Mostoufi-Moab S, Denburg M, Jorgenson E, Sharma P, et al. Muscle deficits in rheumatoid arthritis contribute to inferior cortical bone structure and trabecular bone mineral density. The Journal of Rheumatology. 2017 Dec 1;44(12):1777-85.

27. Blum D, Rodrigues R, Geremia JM, Brenol CV, Vaz MA, Xavier RM. Quadriceps muscle properties in rheumatoid arthritis: insights about muscle morphology, activation and functional capacity. Advances in Rheumatology. 2020 Dec;60:1-9.

28. Turk SA, van Schaardenburg D, Boers M, de Boer S, Fokker C, Lems WF, et al. An unfavorable body composition is common in early arthritis patients: A case control study. PloS One. 2018 Mar 22;13(3):e0193377.

29. Khoja SS, Patterson CG, Goodpaster BH, Delitto A, Piva SR. Skeletal muscle fat in individuals with rheumatoid arthritis compared to healthy adults. Experimental Gerontology. 2020 Jan 1;129:110768.

30. Buttgereit F. Views on glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatology: the age of convergence. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2020 Feb 19:1-8.

31. Kirwan JR, Bijlsma JW, Boers M, Shea B. Effects of glucocorticoids on radiological progression in rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2007(1).

32. Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma JW, Burmester GR, Dougados M, Kerschbaumer A, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2019 update. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2020 Jan 22.

33. Mota LM, Cruz BA, Brenol CV, Pereira IA, Fronza LS, Bertolo MB, et al. Consenso da Sociedade Brasileira de Reumatologia 2011 para o diagnóstico e avaliação inicial da artrite reumatoide. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia. 2011 Jun;51(3):207-19.

34. Lemmey AB, Wilkinson TJ, Perkins CM, Nixon LA, Sheikh F, Jones JG, et al. Muscle loss following a single high-dose intramuscular injection of corticosteroids to treat disease flare in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. European Journal of Rheumatology. 2018 Sep;5(3):160.

35. Yamada Y, Tada M, Mandai K, Hidaka N, Inui K, Nakamura H. Glucocorticoid use is an independent risk factor for developing sarcopenia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: from the CHIKARA study. Clinical Rheumatology. 2020 Jan 14:1-8.

36. Yang LJ, Ouyang ZM, Yang KM, Xu YH, Li HG, Chen C, et al. FRI0034 GLUCOCORTICOID treatment is associated with lower extremity muscle wasting in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2020;79:591.

37. Yamada Y, Tada M, Mandai K, Hidaka N, Inui K, Nakamura H. FRI0083 GLUCOCORTICOID use is associated with deterioration of muscle quality and function: from the chikara study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2020;79:618-619.

38. Pirkmajer S, Kulkarni SS, Tom RZ, Ross FA, Hawley SA, Hardie DG, et al. Methotrexate promotes glucose uptake and lipid oxidation in skeletal muscle via AMPK activation. Diabetes. 2015 Feb 1;64(2):360-9.

39. Hartog A, Hulsman J, Garssen J. Locomotion and muscle mass measures in a murine model of collagen-induced arthritis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2009 Dec 1;10(1):59.

40. Marcora SM, Chester KR, Mittal G, Lemmey AB, Maddison PJ. Randomized phase 2 trial of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for cachexia in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006 Dec 1;84(6):1463-72.

41. Chen J, Sun J, Doscas ME, Ye J, Williamson AJ, Li Y, et al. Control of hyperglycemia in male mice by leflunomide: mechanisms of action. Journal of Endocrinology. 2018 Apr 1;237(1):43-58.

42. Carlson CG, Stein L, Dole E, Potter RM, Bayless D. Agents Which Inhibit NF‐κB Signaling Block Spontaneous Contractile Activity and Negatively Influence Survival of Developing Myotubes. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2016 Apr;231(4):788-97.

43. Engvall IL, Tengstrand B, Brismar K, Hafström I. Infliximab therapy increases body fat mass in early rheumatoid arthritis independently of changes in disease activity and levels of leptin and adiponectin: a randomised study over 21 months. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2010 Oct 1;12(5):R197.

44. Hirano Y, Morisaka A, Kosugiyama H, Inuzuka S, Kamiya T, Mori H, et al. Effects of biological disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug treatment on physical activity, muscle power, agility and inhibition of fall in patients with rheumatoid arthritis -The 2-year results. Ann Rheum Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jun 1;79(Suppl 1):627 LP – 628.

45. Domínguez-Álvarez M, Sabaté-Brescó M, Vilà-Ubach M, Gáldiz JB, Alvarez FJ, Casadevall C, et al. Molecular and physiological events in respiratory muscles and blood of rats exposed to inspiratory threshold loading. Translational Research. 2014 May 1;163(5):478-93.

46. Granado M, Martin AI, Priego T, Lopez-Calderon A, Villanua MA. Tumour necrosis factor blockade did not prevent the increase of muscular muscle RING finger-1 and muscle atrophy F-box in arthritic rats. Journal of Endocrinology. 2006 Oct 1;191(1):319-26.

47. Toussirot É, Mourot L, Dehecq B, Wendling D, Grandclément É, Dumoulin G. TNFα blockade for inflammatory rheumatic diseases is associated with a significant gain in android fat mass and has varying effects on adipokines: a 2-year prospective study. European Journal of Nutrition. 2014 Apr 1;53(3):951-61.

48. Serelis J, Kontogianni MD, Katsiougiannis S, Bletsa M, Tektonidou MG, Skopouli FN. Effect of anti-TNF treatment on body composition and serum adiponectin levels of women with rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical Rheumatology. 2008 Jun 1;27(6):795-7.

49. Metsios GS, Stavropoulos-Kalinoglou A, Douglas KM, Koutedakis Y, Nevill AM, Panoulas VF, et al. Blockade of tumour necrosis factor-α in rheumatoid arthritis: effects on components of rheumatoid cachexia. Rheumatology. 2007 Dec 1;46(12):1824-7.

50. Scott LJ. Tocilizumab: a review in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2017 Nov 1;77(17):1865-79.

51. Younis S, Rosner I, Rimar D, Boulman N, Rozenbaum M, Odeh M, et al. Weight change during pharmacological blockade of interleukin-6 or tumor necrosis factor-α in patients with inflammatory rheumatic disorders: a 16-week comparative study. Cytokine. 2013 Feb 1;61(2):353-5.

52. Tournadre A, Pereira B, Dutheil F, Giraud C, Courteix D, Sapin V, et al. Changes in body composition and metabolic profile during interleukin 6 inhibition in rheumatoid arthritis. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle. 2017 Aug;8(4):639-46.

53. Toussirot E, Marotte H, Mulleman D, Cormier G, Coury-Lucas F, Gaudin P, et al. SAT0167 Increased high molecular weight adiponectin and lean mass during tocilizumab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A 12 month multi-center study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019;78:1157.

54. Fleischmann R. Tofacitinib in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Immunotherapy. 2018 Jan;10(1):39-56.

55. Lundquist LM, Cole SW, Sikes ML. Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. World Journal of Orthopedics. 2014 Sep 18;5(4):504.

56. Kremer JM, Cohen S, Wilkinson BE, Connell CA, French JL, Gomez‐Reino J, et al. A phase IIb dose‐ranging study of the oral JAK inhibitor tofacitinib (CP‐690,550) versus placebo in combination with background methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis and an inadequate response to methotrexate alone. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2012 Apr;64(4):970-81.

57. Novikova DS, Udachkina HV, Markelova EI, Kirillova IG, Misiyuk AS, Demidova NV, et al. Dynamics of body mass index and visceral adiposity index in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib. Rheumatology International. 2019 Jul 1;39(7):1181-9.

58. Winthrop KL. The emerging safety profile of JAK inhibitors in rheumatic disease. Nature Reviews Rheumatology. 2017 Apr;13(4):234-43.

59. Queeney K, Housley W, Sokolov J, Long A. FRI0131 Elucidating the mechanism underlying creatine phosphokinase upregulation with upadacitinib. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019;78:734-735.

60. Chikugo M, Sebe M, Tsutsumi R, Iuchi M, Kishi J, Kuroda M, et al. Effect of Janus kinase inhibition by tofacitinib on body composition and glucose metabolism. The Journal of Medical Investigation. 2018;65(3.4):166-70