Commentary

As the soft tissue- air interface is virtually impenetrable to ultrasound, its utility for evaluating lung pathologies was historically thought to be unfeasible [1]. However, the observation of different artifacts and novel research into their interpretations has helped transform this dogma and develop lung ultrasound as a valuable diagnostic tool in pulmonary diseases. The concept of whole-body ultrasound and especially its approach to examination of the lungs can be dated back to the early nineties [2]. Its portability (making it a point of care technique), safety and a fast learning curve [3], has led to widespread acceptance in clinical practice, and an explosion of studies related to its utility. The medical literature now has an abundance of studies from around the world that have uniformly concluded that ultrasound has a higher diagnostic accuracy than chest X-ray (CXR) in diagnosing pneumonia.

There are special implications of CXR in regard to diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia (VAP). X-rays are often taken in supine and semi-upright positioning, complicating interpretation of radiographs; portable X-ray machines may have limited current and voltage, rendering the image quality poor; and many patients will have some radio-opacities, which may be due to atelectasis or retained secretions, and not just due to pneumonia. Current diagnostic criteria, which utilizes CXR as their core element, including the commonly used Johanson’s criteria and the clinical pulmonary infection score (CPIS) show poor diagnostic performance [4,5]. The superiority of ultrasound in this regard has been reflected in recent studies as well [6-9].

However, in the absence of a reference standard for the diagnosis of VAP, the true sensitivity and specificity of such methods are uncertain, as is their effect on patient care and outcomes. Therefore, diagnostic randomized controlled trials (RCT) are needed to determine the overall clinical utility of a diagnostic approach, and this necessity has been re-iterated in many meta-analyses as well. Diagnostic RCTs, also sometimes referred to as test-treatment RCTs, are randomized comparisons of two diagnostic interventions (one standard and one experimental) with identical therapeutic interventions based on the results of the competing diagnostic interventions. The critical importance of conducting diagnostic RCTs has been clearly stated by Guyatt and colleagues [10] and their advantages over diagnostic cohorts have been thoroughly explained by Rodger M et al. [11]. With this objective, we recently published a study in the Journal of Critical Care [12], to clarify whether ultrasound due to its greater diagnostic accuracy could aid in an earlier therapy of VAP and thus result in improved clinical outcomes.

The study was a prospective, open labeled, diagnostic randomized controlled single center trial conducted in the ICU at Tribhuvan University Teaching Hospital (TUTH), a semi-closed, level III mixed medical-surgical unit. Patients of 18 years or older, who had received more than 48 hours of mechanical ventilation and without the primary diagnosis of pneumonia, were randomized to two different diagnostic strategies for VAP. In the control group, CXR was performed if there were any clinical signs for VAP, such as fever, purulent secretions or raised total counts. Treatment was initiated if the patients met the Johanson’s criteria, which includes the presence of new or progressive consolidation on CXR with at least two of either fever (temperature > 38.0 °C), abnormal total white cell counts (>12 × 109/ml or <4 × 109/ml) or purulent secretions [13]. In the intervention group, patients who developed purulent sputum were monitored for the development of VAP using lung ultrasound. VAP was diagnosed using a combination of purulent sputum, a positive gram stain and the presence of more than one area of small consolidation or an area of consolidation with dynamic air bronchogram.

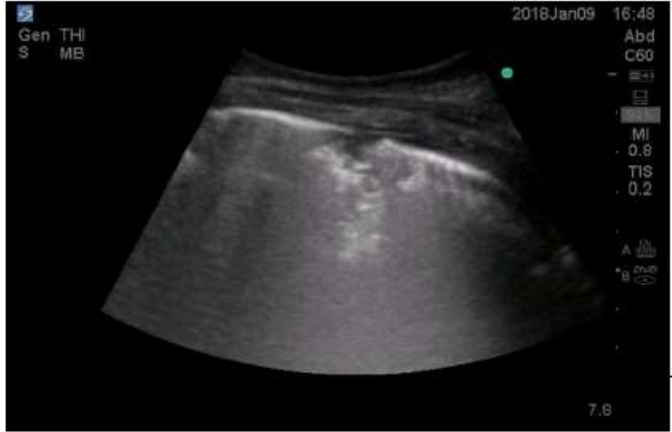

Consolidation in lung ultrasound may be identified as tissue-like echogenicity. Small consolidations (some authors refer to it as subpleural consolidations [6], however some believe the name to be inappropriate [14]) are echo poor regions approximately 0.5 cm in diameter with the presence of shred sign- the irregular border in between the consolidated and aerated lung tissue [15]. Air bronchograms are hyperechoic artifacts within the consolidation and are said to be dynamic if they move centrifugally more than 1 mm during inspiration [16] (Figure 1and 2).

Figure 1: Lung consolidation showing tissue like consistency with air bronchogram.

Figure 2: Small consolidation with shred sign.

In an intention to treat analysis of 200 patients, a total of 88 patients were diagnosed with VAP, 44 patients in each group (incidence of VAP was 44%). In the lung ultrasound group, VAP was diagnosed earlier and was also less severe at the time of diagnosis as suggested by the lower incidence of severe hypoxia (PaO2/FIO2 < 200), vasopressor use and acute kidney injury. A baseline imbalance in the proportion of neurological patients between the groups could, however, have resulted in a similar SOFA (sequential organ failure assessment) score at the time of diagnosis.The primary outcome- ventilator free days (VFD), was found to be significantly more in the lung ultrasound group (8.07+/- 9.9 days versus 3.7+/- 6.4 days, p=0.044). However, this difference did not hold true in those whose empirical antibiotics were resistant to the culprit organism, thus highlighting the importance of initial choice of antibiotics. The higher incidence of inappropriate empirical antibiotic use in the lung ultrasound group could have diluted the effect as well. Other secondary outcomes, which included ICU mortality, lengths of ICU stay, total ventilator days, delta SOFA and the duration of antibiotics were not found to be statistically different between the groups.

Limitations include the absence of blinding, which was difficult due to the nature of the study. The VFD in the control group was found to be much lower than the hypothesized VFD, which could have resulted in an underpowered analysis.The study being a single center analysis performed in a resource limited area with a high incidence of multi-drug resistance VAP also limits external validity.

Though there is a widespread enthusiasm in lung ultrasound that has grown from the need to provide an earlier diagnosis of VAP and its tremendous burden mitigated, there are currently only a fewstudies that have evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of lung ultrasound in VAP.To our knowledge this is the first diagnostic RCT to evaluate the clinical impact of lung ultrasound in VAP diagnosis andprovides additional evidence supporting its use.

Our diagnostic criteria for VAP was based on a prospective multicenter study by Mongodi et al. [6] who compared various combinations of parameters and found VAP lung ultrasound score (VPLUS), in association with direct gram-stain examination to have an area under curveof 0.832, much higher than CPIS (0.574). A very recent systematic review also concluded that small subpleural consolidations and dynamic air bronchograms were the most useful sonographic signs to diagnose VAP in suspected patients [16]. An approach similar to ours has also been recommended in a recent review [18]. This criterion is different than the BLUE protocol (bedside lung ultrasound in emergency), a widely accepted algorithm that helps in diagnosing various acute respiratory conditions including pneumonia, but in patients with respiratory distress [19]. In our approach we used lung ultrasound as a screening tool and monitored asymptomatic patients for early signs of infection. There may be other combinations that may be valuable in diagnosis, but need to be validated.

Lung ultrasound has become the standard of practice in our institute. We only perform CXR on as needed basis approach rather than a daily routine (a practice which has shown to have no additional benefit) [20]; thus, the dependence on lung ultrasound in our daily practice is extensive. Nowadays, we commonly practice using lung ultrasound for diagnosis of VAP. However, a final caveat to all practitioners is that, we should not solely depend on ultrasound image. Many physicians are confused with dynamic air bronchogram, the sign with the highest specificity for pneumonia [16], but less commonly found. Consolidations with static air bronchograms are more common and only represent non-patent airways. They could result from loss of aeration with or without infection. And yes, there are times when obtaining an interpretable image are difficult, such as in obese patients. Therefore, clinical correlation is important and clinical scores with lung ultrasound perform better than lung ultrasound alone. A suspicion of infection as suggested by a combination of clinical parameters (such as purulent sputum, fever, and increased or decreased white cell counts) not explained by other cause along with the finding of consolidation in ultrasound is a reason, we believe, strong enough to initiate antibiotics; although such a practice may vary according to the incidence of VAP rate in that setting (which is particularly high in our setup).

This study can be considered a preliminary study, and cannot be considered evidence enough to change practice, but a reason to contemplate and a step towards larger trials. More substantial outcomes such as mortality or cure rates may be considered. An analysis from our outcomes suggests that at least 300 patients with VAP are required to be randomized for adequate power. With more evidence, lung ultrasound will likely be taken as a standard diagnostic modality for pneumonia.

References

2. Lichtenstein D, Axler O. Intensive use of general ultrasound in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Medicine. 1993 Jun 1;19(6):353-5.

3. See KC, Ong V, Wong SH, Leanda R, Santos J, Taculod J, et al. Lung ultrasound training: curriculum implementation and learning trajectory among respiratory therapists. Intensive Care Medicine. 2016 Jan 1;42(1):63-71.

4. Fàbregas N, Ewig S, Torres A, El-Ebiary M, Ramirez J, de la Bellacasa JP, et al. Clinical diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia revisited: comparative validation using immediate post-mortem lung biopsies. Thorax. 1999 Oct 1;54(10):867-73.

5. Fartoukh M, Maître B, Honoré S, Cerf C, Zahar JR, Brun-Buisson C. Diagnosing pneumonia during mechanical ventilation: the clinical pulmonary infection score revisited. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2003 Jul 15;168(2):173-9.

6. Mongodi S, Via G, Girard M, Rouquette I, Misset B, Braschi A, et al. Lung ultrasound for early diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Chest. 2016 Apr 1;149(4):969-80.

7. Zagli G, Cozzolino M, Terreni A, Biagioli T, Caldini AL, Peris A. Diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia: a pilot, exploratory analysis of a new score based on procalcitonin and chest echography. Chest. 2014 Dec 1;146(6):1578-85.

8. Berlet T, Etter R, Fehr T, Berger D, Sendi P, Merz TM. Sonographic patterns of lung consolidation in mechanically ventilated patients with and without ventilator-associated pneumonia: a prospective cohort study. Journal of Critical Care. 2015 Apr 1;30(2):327-33.

9. Xirouchaki N, Magkanas E, Vaporidi K, Kondili E, Plataki M, Patrianakos A, et al. Lung ultrasound in critically ill patients: comparison with bedside chest radiography. Intensive Care Medicine. 2011 Sep 1;37(9):1488.

10. Guyatt GH, Tugwell PX, Feeny DH, Haynes RB, Drummond M. A framework for clinical evaluation of diagnostic technologies. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1986 Mar 15;134(6):587.

11. Rodger M, Ramsay T, Fergusson D. Diagnostic randomized controlled trials: the final frontier. Trials. 2012 Dec 1;13(1):137.

12. Pradhan S, Shrestha PS, Shrestha GS, Marhatta MN. Clinical impact of lung ultrasound monitoring for diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia: A diagnostic randomized controlled trial. Journal of Critical Care. 2020 Apr 14.

13. JohansonJr WG, Pierce AK, Sanford JP, Thomas GD. Nosocomial respiratory infections with gram-negative bacilli: the significance of colonization of the respiratory tract. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1972 Nov 1;77(5):701-6.

14. Lichtenstein DA. Current misconceptions in lung ultrasound: a short guide for experts. Chest. 2019 Jul 1;156(1):21-5.

15. Miller A. Practical approach to lung ultrasound. BJA Education. 2016 Feb 1;16(2):39-45.

16. Lichtenstein D, Mezière G, Seitz J. The dynamic air bronchogram: a lung ultrasound sign of alveolar consolidation ruling out atelectasis. Chest. 2009 Jun 1;135(6):1421-5

17. Staub LJ, Biscaro RR, Maurici R. Accuracy and applications of lung ultrasound to diagnose ventilator-associated pneumonia: a systematic review. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2018 Aug;33(8):447-55.

18. Bouhemad B, Dransart-Rayé O, Mojoli F, Mongodi S. Lung ultrasound for diagnosis and monitoring of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Annals of Translational Medicine. 2018 Nov;6(21).

19. Lichtenstein DA, Meziere GA. Relevance of lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of acute respiratory failure: the BLUE protocol. Chest. 2008 Jul 1;134(1):117-25.

20. Graat ME, Stoker J, Vroom MB, Schultz MJ. Can we abandon daily routine chest radiography in intensive care patients?. Journal of Intensive Care Medicine. 2005 Jul;20(4):238-46.