Abstract

This paper presents a mathematical proof of the equivalence between the Human Language-based Consciousness (HLbC) model and Bayesian inference, exploring their connection within neural information processing. The HLbC model posits that consciousness emerges through a process involving the observation of external events, the matching of those events to past memories, unconscious action selection, and post-hoc recognition of actions as conscious decisions. These processes closely align with the principles of Bayesian inference, where prior beliefs are updated based on new evidence to form posterior probabilities, thereby minimizing prediction errors and optimizing behavior. The paper highlights the dynamic feedback mechanisms shared by both frameworks, demonstrating how unconscious probabilistic action selection in the HLbC model parallels the sampling process in Bayesian inference. Furthermore, the retrospective recognition of actions in the HLbC model is shown to correspond to Bayesian updating, suggesting a unified approach to understanding consciousness generation. This research provides a robust theoretical foundation for applying probabilistic reasoning and feedback mechanisms to the study of consciousness, offering insights that can extend beyond neuroscience to fields like artificial intelligence and control systems.

Keywords

HLbC model, Bayesian inference, Neural information processing, Consciousness generation, Probabilistic reasoning, Posterior distribution updating

Introduction

The elucidation of consciousness remains one of the most profound challenges in modern neuroscience. Central to this endeavor is understanding how the brain processes information to generate conscious experience. Recent advances in computational neuroscience have increasingly suggested that the brain operates on principles akin to Bayesian inference, whereby sensory data are integrated with prior knowledge to form optimal beliefs and guide behavior. This Bayesian framework has gained significant traction for explaining a variety of neural functions, including perception, motor control, and decision-making [1-4].

Bayesian inference is a probabilistic model for updating prior beliefs based on new evidence to calculate posterior probabilities. It provides a robust framework for understanding how the brain processes uncertain sensory inputs while continuously updating internal models to minimize prediction errors [5,6]. Hierarchical Bayesian models have been proposed to explain how sensory data are processed and integrated within the visual cortex [7]. The theory of predictive coding, closely linked to Bayesian inference, posits that the brain continuously predicts incoming sensory signals and updates these predictions based on mismatches between expected and actual inputs [8]. Friston's free-energy principle [9] further extends this idea, suggesting that the brain minimizes free-energy, or prediction error, to explain its core functions.

Recent studies have expanded Bayesian models to capture more complex functions like causal inference and sensory integration across multiple modalities [10,11]. The role of Bayesian inference in multisensory integration and perceptual decision-making is a key area of study in cognitive neuroscience [12]. Additionally, the Bayesian brain hypothesis has been extended to higher-level cognitive processes such as learning, attention, and even social cognition [13,14]. These advances illustrate the versatility of the Bayesian framework for modeling both basic and complex cognitive functions.

In motor control, Bayesian models have been applied to explain how the brain integrates uncertain sensory feedback to optimize movements. The Bayesian brain hypothesis has played a critical role in elucidating how the brain selects optimal actions under uncertainty [15,16]. This probabilistic framework is particularly suited for explaining how the brain makes complex decisions in the face of noisy and incomplete information [17,18].

Despite the progress in understanding how the brain employs Bayesian inference, significant challenges remain in fully modeling human cognition and consciousness. To address these challenges, the authors have developed the Human Language based Consciousness (HLbC) model, which builds on the foundations of the Bayesian brain theory while introducing a novel perspective on the mechanisms of consciousness generation [19-21]. The HLbC model posits that consciousness is not merely a byproduct of neural activity but is fundamentally shaped by the structure of human language, operating through a process of matching observed events to past episodic memories, generating behavior, and post-hoc recognition of those behaviors as conscious decisions [19].

The HLbC model comprises several key steps. It begins with the observation of events, followed by a process of matching these events to past memories, selecting actions, and ultimately recognizing the selected actions as conscious decisions. This model aligns closely with the processes observed in Bayesian inference, where prior beliefs are updated in light of sensory data to generate posterior beliefs. Moreover, the HLbC model explains how unconscious actions are retrospectively recognized as conscious decisions, contributing to our understanding of complex psychological phenomena such as decision-making under uncertainty and the behavior of split-brain patients [22].

The HLbC model’s probabilistic selection of actions based on past experiences mirrors the sampling processes in Bayesian inference [23]. By combining the unconscious selection of actions with post-hoc conscious recognition, the HLbC model offers a dynamic and adaptive framework for understanding how the brain navigates complex environments and generates goal-directed behavior.

Furthermore, the HLbC model’s control system, which operates by minimizing prediction errors through sequential adjustments, closely parallels the feedback mechanisms found in Bayesian brain models. Both frameworks share the objective of minimizing errors or uncertainty to optimize future behavior [4,5]. In this way, the integration of probabilistic reasoning and feedback mechanisms within the HLbC model is consistent with the predictive coding and Bayesian inference models proposed to explain brain function [24,25].

In this paper, we aim to mathematically prove the equivalence between the HLbC model and the Bayesian framework in neuroscience. By formalizing the correspondence between the observation-to-action cycle and post- hoc recognition of unconscious behavior, the HLbC model offers a structured approach to understanding how the brain achieves adaptive, goal-oriented control. The primary contribution of this research is to unify the perspectives of language-based consciousness and probabilistic reasoning, providing a novel theoretical framework for explaining how conscious decision-making is generated.

Equivalence of the HLbC Model and Control Systems Targeting

Brief summary of HLbC model

The authors have proposed the HLbC (Human Language based Consciousness) model as a novel framework for understanding consciousness [19]. To validate this model, they have investigated its capacity to explain various psychological phenomena, such as visual illusions and behavioral economics [20]. Furthermore, the model has been applied to cases involving split-brain patients, where the severance of the corpus callosum results in the functional separation of the brain’s left and right hemispheres [22]. In addition, discussions have been held regarding the model’s compatibility with the psychological perception of time and its potential alignment with QBism, an interpretation of quantum mechanics [26].

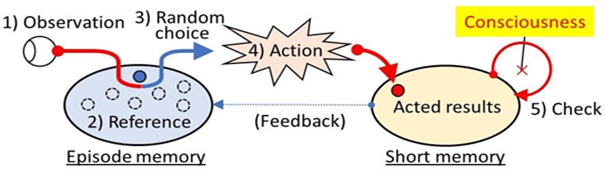

For further details, please refer to previous reports, but the HLbC model is structured as follows (Figure 1): STEP-1: Observation: The system observes external events and acquires relevant information. STEP-2: Matching and Selection of Options: The observed event is compared against past memories, and the system selects the most appropriate action from available options. STEP-3: Action: The selected action is executed, and the outcome is obtained. STEP-4: Memory: The outcome is stored in short-term memory. STEP-5: Post-hoc Consciousness: Based on the outcome and memory, consciousness is formed retrospectively.

Figure 1. Concept of HLbC model.

The HLbC model explains consciousness through five sequential stages: observation, matching with episodic memory, unconscious selection and action, short-term memory of the action, and retrospective recognition of the action as consciousness. This framework primarily addresses the cognitive function of consciousness, emphasizing the processes occurring between stimuli and behavior.

However, in the brain, these processes are carried out continuously and interdependently, supporting functions such as problem-solving—what could be termed "consciousness for problem-solving." This role of the brain is often modeled using Bayesian inference, which describes how the brain predicts and updates information from the external world to select optimal actions.

This paper extends the HLbC model to explore how consciousness functions beyond mere cognition, specifically in the context of problem-solving. Additionally, we aim to investigate whether the extended model aligns with the principles of the Bayesian brain. Specifically, we will examine how each stage of the HLbC model functions within a problem-solving framework and how it corresponds to the brain's broader decision-making processes.

Through this analysis, we seek to establish whether the HLbC model can serve as a comprehensive framework for understanding not only cognitive consciousness but also the role of consciousness in achieving goals. Furthermore, we will assess whether this extended model maintains coherence with the Bayesian framework, ultimately providing deeper insights into the continuous and goal-directed nature of consciousness.

The HLbC model defines the emergence of consciousness through five sequential processes. The development of consciousness in this model occurs through reactions based on external input data and subsequent recognition through "post hoc" evaluations. Each step corresponds to a sequential optimization process in a control system directed towards a target value and is further related to Bayesian inference. This chapter introduces the parameters and equations necessary to demonstrate the relationship with Bayesian inference later on, while mathematically formalizing the correspondence between the HLbC model and control systems.

Step 1: Observation of events and acquisition of input data

The first step of the HLbC model is to observe events in the external world. This observation serves as the basis for the brain to process sensory data and determine subsequent actions.

Mathematical expression

In the control system, the observed input data is represented as x(t). Here, t indicates time, and the system receives input data at each time step. This can be described as:

Step 2: Matching observed events with episodic memory

The brain matches the observed event x(t) with past episodic memories to determine how to respond. Multiple past memories exist, each associated with different outcomes.

Mathematical expression

The system internally retains pairs of past observed data x(t′) and outcomes y(t′), represented as {( x(t′), y(t′))}. At this time, the system retrieves corresponding past episodic memories for the current input data x(t) as follows:

This matching process corresponds to an internal search based on the input data.

Step 3: Probabilistic selection of episodes and unconscious behavior

The brain randomly selects one from past episodic memories and unconsciously reacts based on that memory.

At this stage, the behavior is unconscious, and its optimality is not evaluated.

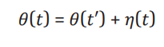

Mathematical expression

In the system, the output is generated using a randomly selected past parameter θ(t′) as follows:

Here, η(t) represents a random fluctuation term. Using this parameter, the output y(t) is generated as follows:

Where f(x(t),θ(t)) is the system's output function, and ε(t) represents noise.

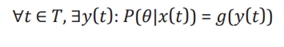

In this step, the term "probabilistic selection" refers to the probabilistic nature of action selection, which aligns with the sampling process in Bayesian inference. Rather than purely probabilistic selection, the brain selects an action θ(t) based on a probability distribution derived from past experiences (the prior distribution). This process can be described as:

where P(θ|x(t)) represents the probability of selecting θ(t) given the current observation x(t). The random fluctuation term η(t) introduces variability, reflecting the uncertainty inherent in real-world decision-making.

Step 4: Short-term memory of action results

The results of unconscious actions are accumulated in the brain's short-term memory and used for subsequent judgments. Similarly, in a control system, the output results are temporarily recorded. At this stage, the system retains the output y(t) as temporary memory at time t, which is utilized for optimization in the next step:

Step 5: Cognition of short-term memory and post-hoc consciousness

Ultimately, the brain recognizes action results based on short-term memory and "consciousness"-izes them. This corresponds to the process in which the system evaluates output and adjusts the next control parameters based on the error with respect to the target value.

The system calculates the error e(t) with respect to the target value ytarget and updates the next parameter θ(t+1) based on this error. This process can be expressed as:

Based on this error e(t), the parameters at the next time t+1 are updated as follows:

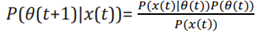

In Bayesian inference, the posterior distribution is updated using Bayes' theorem: P (θ | x(t)) = P ( x(t) | θ) P (θ) / P (x (t)). Here, the prior P(θ) is updated based on the likelihood P ( x(t) | θ), which reflects the new data. This corresponds to the adjustment of θ (t+1) in the control system, where the parameter is updated to minimize the error e(t). Here, the prior P(θ) is updated based on the likelihood P(x(t)|θ), which reflects the new data. This corresponds to the adjustment of θ(t+1) in the control system, where the parameter is updated to minimize the error e(t). The learning rate α dictates how strongly the error influences the parameter update, in a manner similar to how the likelihood term P( x(t) | θ) in Bayesian inference modulates the influence of new data on the posterior distribution. This analogy between the feedback mechanism in control theory and the posterior update in Bayesian inference shows that both systems aim to minimize error through iterative refinement.

The "post-hoc" recognition process in the HLbC model corresponds to the updating of the posterior distribution in Bayesian inference. In Bayesian inference, new observational data is used to update prior beliefs, refining the posterior distribution P(θ|x(t)). Similarly, in the HLbC model, the brain retrospectively recognizes the results of unconscious actions, integrating new information (outcomes) to update the internal model (prior beliefs) and adjust future actions. This process reflects the core principle of Bayesian updating, where posterior probabilities are revised based on new evidence.

The equations and parameters developed in this chapter serve as a foundation for proving the relationship with Bayesian inference in the next chapter. In particular, it will be demonstrated that the post-hoc recognition (Step 5) and unconscious probabilistic selection (Step 3) play crucial roles in the update of posterior probabilities in Bayesian inference. Central to Bayesian inference are the prior distribution P(θ), the observational data P( x(t) | θ), and the posterior distribution P(θ|x(t)), which will be clarified in how they manifest within the HLbC model and control systems in the next chapter.

Thus, the processes of consciousness creation based on the HLbC model and the parameter adjustment processes in control systems are mathematically aligned at each step, ultimately demonstrating a strong correlation with Bayesian inference.

Bayesian Inference Model of the Brain (Mathematical Formalization)

In this section, we formalize decision-making in the brain as Bayesian inference, representing each step with equations and logical symbols.

The foundation of Bayesian inference is defined as follows:

Here:

- θ: A parameter (e.g., action selection or hypothesis).

- x: Observation data.

- P(θ | x): The posterior probability, representing the probability of θ after observing x (Bayes, 1763).

- P(x | θ): The likelihood, indicating the probability of observing data x given hypothesis θ.

- P(θ): The prior probability, representing the initial belief about θ.

- P(x): The marginal likelihood of observation x.

Prior distribution

The prior belief P(θ) represents the brain's initial hypothesis or belief based on past experiences. It is formed as the cumulative knowledge derived from prior observations [27].

Likelihood

The likelihood function P(x | θ) evaluates how well the hypothesis θ fits the new observational data xx. It reflects the extent to which the new data supports the given hypothesis [6].

Updating the posterior distribution: The posterior probability is updated using Bayes' theorem:

The application of Bayesian inference to brain function provides a powerful framework for understanding how the brain processes external information and makes decisions. It is believed that the brain updates information sequentially and makes probabilistically optimal judgments, akin to Bayesian inference.

Basics of Bayesian inference

Bayesian inference is a method for updating existing knowledge (prior information) based on newly acquired evidence (observational data) to calculate posterior probabilities. This is grounded in Bayes' theorem, expressed as follows:

Here:

P(hypothesis | data) is the posterior probability of the hypothesis given the data.

P(data | hypothesis) is the likelihood of observing the data if the hypothesis is true.

P(hypothesis) is the prior probability of the hypothesis.

P(data) is the overall probability of observing the data (marginal likelihood).

Bayesian inference updates the plausibility of hypotheses based on prior probabilities and new observational data (Bayes, 1763).

The Bayesian inference process in the brain: The brain continuously receives uncertain information from the environment and uses it to make inferences and decisions. Bayesian inference models this process by updating prior beliefs with new data, allowing the brain to derive optimal interpretations of its surroundings [27].

Prior and posterior information: The brain maintains hypotheses about the environment, analogous to the prior probability in Bayesian inference. As new sensory information is acquired, these hypotheses are updated, refining the brain's understanding of the environment [6].

Observational Data (Sensory input): The brain acquires information from the environment via sensory inputs like vision, hearing, and touch. This sensory data acts as the observational input in Bayesian inference. Based on this data, the brain updates its prior beliefs and computes posterior probabilities [3].

Posterior inference: Using Bayes' theorem, the brain updates its beliefs in light of new evidence, leading to the derivation of the most plausible hypothesis given the sensory input. For example, the brain might update its prediction of whether a distant object is a person or a tree based on new visual data on a cloudy day.

Feedback loops and minimization of prediction error: The brain’s inferential process is iterative, with feedback loops that compare prior hypotheses with new data. The brain aims to minimize the prediction error—the difference between its expectations and the actual data—through continuous updating [4].

Action selection: The brain selects the next action based on the posterior probability P(θ | x). The optimal action θ∗ is defined as:

This expression signifies that the brain aims to maximize the posterior probability when making decisions, thus selecting the action most consistent with the observed data [4].

Bayesian Brain Hypothesis

This conceptual framework is referred to as the Bayesian Brain Hypothesis, asserting that the brain possesses the following characteristics [3]:

- Probabilistic inference: The brain performs inference based on hypotheses that have probability distributions. All sensory information and beliefs are accompanied by uncertainties, which the brain manages.

- Dynamic updating: Over time, the brain updates beliefs with each new piece of information obtained. This process is sequential and adapts flexibly to environmental changes.

- Minimization of prediction error: The goal of the brain is to minimize the discrepancies between predictions about the state of the environment and actual observations. The brain selects appropriate hypotheses to reduce prediction errors.

Concrete examples of the Bayesian Brain Hypothesis

Visual cognition: For example, the functioning of the visual system can be explained through Bayesian inference. In visual cognition, the brain continually predicts variations in external objects and light. If it suddenly gets dark, the brain utilizes prior information (e.g., past experiences of it getting dark in the evening) to formulate the hypothesis that "it's evening, so it's normal to get dark," thereby interpreting new information accordingly [4].

Motor control: In the realm of motor control, Bayesian inference is similarly applied. When executing movements, the brain processes uncertain information regarding hand and body positions (such as feedback from muscles) while optimizing movements toward a target location [27]. It enhances movement precision through Bayesian reasoning.

Decision making: In decision-making processes, the brain processes uncertain environmental information to select the most plausible options. For example, when making risky choices, the brain evaluates the probabilities of risks based on past experiences and observational data, facilitating optimal decision-making [3].

Convergence of Bayesian inference models and brain functions: The alignment of Bayesian inference with brain function is attributed to the following characteristics of the brain:

- Dealing with uncertainty: The brain continuously receives imperfect and noisy sensory information that must be interpreted appropriately. The framework of Bayesian inference effectively handles uncertainty probabilistically, yielding the most reasonable interpretations.

- Learning based on experience: The brain utilizes prior experiences (prior information) to adapt to new situations.

- Bayesian inference combines prior information with new observations to learn and adapt sequentially.

- Sequential updating: The brain updates hypotheses and beliefs whenever new information is obtained. Similarly, Bayesian inference is characterized by the sequential updating of probability distributions based on observational data.

Bayesian states androvides a highly effective framework for describing the processes by which the brain processes sensory inputs, infers external states, and makes decisions. The Bayesian brain hypothesis suggests that the brain performs probabilistic updates of beliefs based on external information, applied in areas such as perception, motor control, and decision-making. This model helps to illuminate the brain's efficient and flexible reasoning capabilities.

A Mathematical Proof of the Equivalence between the HLbC Model and Bayesian Inference

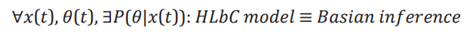

This chapter rigorously proves the mathematical equivalence between the Human Language-based Consciousness (HLbC) model and Bayesian inference, using logical symbols and equations. It demonstrates how each step of the HLbC model corresponds to the processes of Bayesian inference, establishing their logical consistency.

Premises and definitions

We begin by defining the key elements of both the HLbC model and Bayesian inference, establishing a clear correspondence between the two frameworks.

- Observation Data x(t): In both models, observation data refers to external inputs received by the system at time t. In the HLbC model, this corresponds to sensory inputs or stimuli observed by the individual, while in Bayesian inference, it is the observed data used to update beliefs [5].

- Behavior Parameter θ(t): This represents the internal state or the decision variable in both frameworks. In the HLbC model, θ(t) refers to the chosen action or behavior at time t, while in Bayesian inference, it corresponds to the parameter being estimated or updated.

- Episodic Memory MMM: In the HLbC model, episodic memory refers to the stored information from past experiences, which informs current behavior. In Bayesian inference, this is analogous to the prior distribution P(θ), which represents the accumulated knowledge from past data [3,4].

- Posterior Distribution P(θ?x(t)): The probability distribution of the parameter θ after incorporating new observation data x(t). In both models, this reflects the updated belief or decision based on new information.

- The goal of this section is to establish the mathematical equivalence of these elements between the HLbC model and Bayesian inference.

Correspondence of observation data

In Bayesian inference, observation data x(t) is information obtained from the environment. The HLbC model also treats the observation data x(t) at time t in the same way. We define this as:

This indicates that the observation data at time t is identical to the observation data in Bayesian inference. Thus, the observation step is mathematically consistent across both models.

Equivalence of prior distribution and episodic memory

In both models, observation data x(t) influences the system's internal state, which then guides future actions or belief updates. In Bayesian inference, observation data updates the prior distribution P(θ) based on new evidence. In the HLbC model, episodic memory M(t−1), which stores past observations and actions, serves a similar role in shaping the prior distribution.

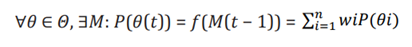

This relationship can be expressed as:

Here, P(θ(t)) represents the prior distribution at time t, which is a function of the episodic memory M(t−1), reflecting past experiences, wi represents the weight based on past memories and observations. Thus, each new observation modifies the prior distribution, maintaining a consistent mechanism between the HLbC model and Bayesian inference for updating beliefs and guiding actions based on historical data.

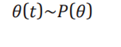

Mathematical correspondence of unconscious action selection and sampling

In the HLbC model, the unconsciously selected action θ(t) is determined by sampling from the prior distribution. This corresponds to the sampling process in Bayesian inference. Sampling in Bayesian inference can be expressed as:

This indicates that the action parameter θ(t) is chosen according to the prior distribution P(θ). When applied to the HLbC model, the unconscious action selection can be expressed as:

Here, η(t) represents a random noise term, indicating that the action is selected randomly from the prior distribution. This shows that the processes of unconscious action selection in both models are mathematically equivalent.

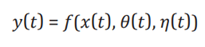

Feedback function and update of posterior distribution

In the HLbC model, the feedback function f(x(t),θ(t),η(t)) determines the next action y(t) based on the observation data x(t), the behavior parameter θ(t), and a noise term η(t), reflecting uncertainty. The feedback function operates by adjusting the current behavior to optimize future actions, similar to how a control system minimizes the error between its output and a target value.

Mathematical Expression:

Here, e(t)=ytarget−y(t) represents the error between the target value and the current output. The system adjusts the behavior parameter θ(t) to minimize the error, resulting in the following update for the next behavior parameter:

where α is the learning rate that controls the magnitude of the adjustment. This update rule corresponds to a gradient- based optimization that aims to minimize the prediction error.

In Bayesian inference, the posterior distribution is updated based on the observation data x(t). This update process refines the prior belief P(θ) in light of new evidence x(t), and is expressed as:

Here, P(θ(t+1)?x(t)) represents the posterior probability of the parameter θ(t+1) after observing x(t). This process mirrors the feedback function in the HLbC model, where the next action is influenced by the previous action and observation, both aiming to minimize uncertainty or prediction error.

This analogy between feedback in the HLbC model and the posterior update in Bayesian inference illustrates that both systems operate iteratively, refining their predictions and actions through continuous updates based on new data and outcomes.

Short-term memory of action results and update of posterior distribution

In the HLbC model, the result y(t) of the action θ(t) is retained in short-term memory and influences subsequent action selection. This corresponds to the update process of the posterior distribution in Bayesian inference.

This logical expression indicates that the short-term memory of action results corresponds to the update of the posterior distribution [6].

Equivalence of backward recognition and optimization

The backward recognition process in the HLbC model is equivalent to the optimization process in Bayesian inference. In Bayesian inference, the next action θ(t+1) is selected based on the posterior distribution and updated using gradient-based optimization:

Here, e(t) represents the difference between the predicted value and the actual outcome (the prediction error), and α is the learning rate, which controls how much the update is influenced by the gradient of the error function with respect to θ.

This process signifies optimization towards minimizing the prediction error for the next action selection. In the HLbC model, the backward recognition of unconscious actions is similarly represented by adjusting the behavior based on feedback from prior outcomes, aligning with the same optimization principles used in Bayesian inference. Both models aim to minimize the error between expected and actual outcomes, thereby refining future decisions. The optimization process in Bayesian inference, through gradient descent, corresponds directly to the backward recognition process in the HLbC model, where actions are iteratively adjusted based on the feedback from previous decisions.

Comprehensive proof of equivalence

Through the examination of each step, we have established that the processes in the HLbC model and Bayesian inference are mathematically equivalent. In summary, we can express this equivalence as:

This logical statement confirms that the HLbC model and Bayesian inference are mathematically equivalent in their entirety. This validation reinforces that the processes underlying consciousness generation in the HLbC model and decision-making in Bayesian inference share the same mechanism.

Conclusion

In this paper, we aimed to mathematically demonstrate the equivalence between the consciousness generation process based on the Human Language based Consciousness (HLbC) model and the brain's information processing model grounded in Bayesian inference. The HLbC model encompasses the observation of events, the matching with past episodic memories, the unconscious selection of actions, and the cognition of the results of those actions. This "post-hoc" process of consciousness generation corresponds to the updating of posterior probabilities in Bayesian inference, contributing to the determination of optimal action choices.

In Chapter 2, we showed that each stage of the HLbC model aligns with feedback loops in control systems. In a control system, the sequential adjustment of parameters to bring outputs closer to target values is inherently equivalent to the consciousness generation process of the HLbC model, demonstrating a consistent alignment with the brain's information processing.

Chapter 3 provided an overview of the brain's Bayesian inference model. Bayesian inference is widely supported as a method for updating prior knowledge based on observational data to select optimal actions. Much of the brain's decision-making and sensory processing is based on this Bayesian inference framework, forming the foundation for the prediction and updating of behaviors.

In Chapter 4, we mathematically proved the equivalence between the HLbC model and Bayesian inference. We explicitly showed how the processes of observation, memory matching, unconscious action selection, short-term memory of action results, and final cognition correspond to the updating of prior probabilities, observational data, likelihoods, and posterior probabilities in Bayesian inference. Notably, the process of random action selection and subsequent recognition correspond to judgments based on the updating of posterior distributions.

Given these findings, it is confirmed that the HLbC model is not merely a theoretical construct but aligns with the actual mechanisms of information processing in the brain. Furthermore, this equivalence provides an important framework that can be applied not only in neuroscience but also in the design of artificial intelligence and control systems. The linkage between Bayesian inference and the HLbC model proves useful, particularly in constructing AI systems that guide conscious decision-making.

Future research is anticipated to explore further applications of the HLbC model and Bayesian inference, as well as connections with specific neurophysiological evidence. This will enhance our understanding of the processes of consciousness generation and pave the way for the development of AI with consciousness.

References

2. Yuille A, Kersten D. Vision as Bayesian inference: analysis by synthesis? Trends Cogn Sci. 2006 Jul;10(7):301-8.

3. Hohwy J. The predictive mind. Oxford University Press. 2013.

4. Clark A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2013;36(3):181-204.

5. Friston K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 Feb;11(2):127-38.

6. Knill DC, Pouget A. The Bayesian brain: the role of uncertainty in neural coding and computation. Trends Neurosci. 2004 Dec;27(12):712-9.

7. Lee TS, Mumford D. Hierarchical Bayesian inference in the visual cortex. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 2003 Jul;20(7):1434-48.

8. Clark A. Surfing uncertainty: Prediction, action, and the embodied mind. Oxford University Press; 2015 Oct 2.

9. Friston K. The free-energy principle: a rough guide to the brain? Trends Cogn Sci. 2009 Jul;13(7):293-301.

10. Körding KP, Wolpert DM. Bayesian integration in sensorimotor learning. Nature. 2004 Jan 15;427(6971):244-7.

11. Shams L, Beierholm UR. Causal inference in perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010 Sep;14(9):425-32.

12. Odegaard B, Shams L. The effects of selective attention on visual multisensory integration. Journal of Vision. 2016;16(2):15.

13. Gershman SJ, Daw ND. Reinforcement Learning and Episodic Memory in Humans and Animals: An Integrative Framework. Annu Rev Psychol. 2017 Jan 3;68:101-128.

14. Ma WJ, Beck JM, Latham PE, Pouget A. Bayesian inference with probabilistic population codes. Nat Neurosci. 2006 Nov;9(11):1432-8.

15. Todorov E. Optimality principles in sensorimotor control. Nat Neurosci. 2004 Sep;7(9):907-15.

16. Körding K, Fukunaga I, Howard I, Ingram J, Wolpert D. Bayesian integration of visual and proprioceptive information. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2007;97(2):220-9.

17. Shadmehr R, Krakauer JW. A computational neuroanatomy for motor control. Exp Brain Res. 2008 Mar;185(3):359-81.

18. Ma WJ, Jazayeri M, Shadlen MN. The origins of time in the brain. Neuron. 2014;84(2):362-77.

19. Hebishima H, Arakaki M, Dozono C, Frolova H, Inage S. Mathematical definition of human language, and modeling of will and consciousness based on the human language. Biosystems. 2023 Mar;225:104840.

20. Arakaki M, Dozono C, Frolova H, Hebishima H, Inage S. Modeling of will and consciousness based on the human language: Interpretation of qualia and psychological consciousness. Biosystems. 2023 May;227-228:104890.

21. Yamada M, Matsumoto M, Arakaki M, Hebishima H, Inage S. Estimation of discrepancy of color qualia using Kullback-Leibler divergence. Biosystems. 2023 Oct;232:105011.

22. Arakaki M, Hebishima H, Inage SI. Interpretation and modelling of the brain and the split-brain using the HLbC (Human Language based Consciousness) model. Neurosci Chron. 2024;4(1):1-4.

23. Hebishima H, Inage S. Modeling of psychological time cognition with Human Language based Consciousness model. Journal of Biomed Research. 2024;5(1):96-102.

24. Botvinick M, Toussaint M. Planning as inference. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012 Oct;16(10):485-8.

25. Gershman SJ, Horvitz EJ, Tenenbaum JB. Computational rationality: A converging paradigm for intelligence in brains, minds, and machines. Science. 2015 Jul 17;349(6245):273-8.

26. Hebishima H, Inage S. Mathematical modeling of consciousness based on the human language-An interpreting measurement problem in quantum mechanics. The Neuroscience Chronicles. 2024;4(1):15-20.

27. Doya K. Reinforcement learning in continuous time and space. Neural Computation. 2000;12(1):219-45.