Abstract

Medical imaging is the process of creating visual pictures of the inside of the human body for diagnostic and treatment purposes. This article provides an overview about different types of medical imaging. Each technique is used in different circumstances. There is no single method available that eliminates the risks while maintaining benefits of imaging. Furthermore, as a perspective, recent technical innovations such as sonogenetics that combines the advantage of ultrasound and genetic engineering via sonosensitive mediators for non-invasively modulate cellular functions with the potential application in disease treatment and management is also discussed.

Keywords

Medical imaging, Ultrasound, Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound, Optogenetics, Sonogenetics, Sonosensitive mediators, Expression vector, Glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor, Muscle LIM protein

Introduction

Radiation is the emission or transmission of energy in the form of waves or particles through space or a material medium [1,2]. This includes (a) electromagnetic radiation consisting of photons, such as radio waves, microwaves, visible light, ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays, etc.; (b) particle radiation consisting of particles of non-zero rest energy, such as alpha radiation (?), beta radiation (?), etc.; (c) acoustic radiation, such as ultrasound, sound, etc.; and (d) gravitational radiation, in the form of gravitation waves, ripples in spacetime. Radiation is often categorized as a low energy form, called “non-ionizing radiation” such as radio waves, and a high energy form, more than 10 electron volts, called “ionizing radiation” which is enough to ionize atoms and molecules and break chemical bonds, such as X-rays, gamma rays (?), and radioactive materials that emit ?, or ? radiation, etc. We are exposed to radiation in our everyday life. Some of the most familiar sources of radiation include the sun, microwave ovens in our kitchens, etc. Most of this radiation carries no risk to our health, but some does. Depending on the type of radiation either ionizing or non-ionizing, different measures must be taken to protect our body and the environment from its effects, while allowing us to benefit from its many applications such as health from medical procedures via medical imaging, and energy from producing electricity via, for example solar energy, etc.

Medical imaging is the process of creating visual pictures of the inside of the human body for diagnostic and treatment purposes [3,4]. There are many types of medical imaging, and more methods for imaging are being invented as technology advances. The main types of imaging used in modern medicine are radiography, computed tomography (CT), fluoroscopy, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound (US), nuclear medicine (NM), and molecular imaging (MI). Medical imaging techniques have had a major impact on public health over the last century. This article aims to highlight the basic understandings of these different types of medical imaging. Furthermore, as a perspective, sonogenetics that combines the advantage of ultrasound and genetic engineering via sonosensitive mediators for non-invasively modulate cellular functions with the potential application in disease treatment and management is also discussed.

Medical Imaging Techniques Overview

There are many excellent reviews that describe the different types of medical imaging techniques in detail but are otherwise beyond the scope of this article. Herein are the basic understandings of this issue.

Radiography

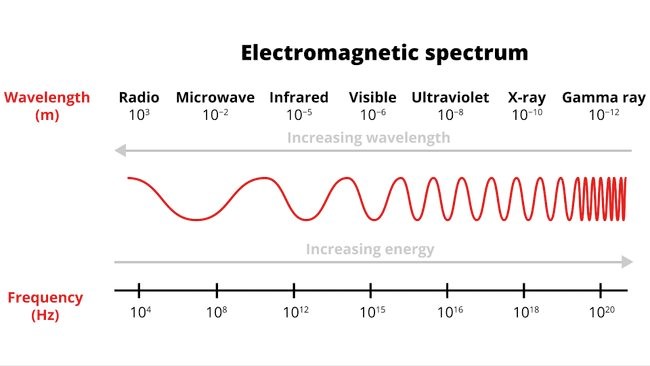

This technique uses electromagnetic radiation to take images of the inside of the body. The most well-known and common form of radiography is X-ray, which is a form of high-energy electromagnetic radiation (Figure 1) and can pass through most objects, including the body. For this procedure, an X-ray machine beams high-energy waves onto the body. Image produced by X-rays are due to the different absorption rates of different tissues. The machine transfers the results of the X-rays onto a film (radiograph) recording of the X-ray image. Air absorbs least, so lungs look black on a radiograph. The hard tissues and denser structures such as bones are showing in white (due to calcium in bones absorbs X-rays the most). Fat and other soft tissues, such as skin and organs absorb less, and look gray. Tumors are usually denser than the tissues surrounding them, so they often show up as lighter shades of gray than the surrounding tissues. A bone tumor will cause destruction and sometimes, aberrant of calcification. The bone at the site of the cancer may look then irregular, spiky, instead of solid.

Figure 1. Electromagnetic spectrum. High frequency using gamma rays, X-rays or ultraviolet light is ionizing and can cause damage to the human

body leading to cancer.

Computer Tomography (CT)

This technique uses a series of X-rays plus a computer to produce a cross-sectional image of the inside of the body. CT scan can detect smaller abnormalities than can be found with a conventional X-ray, and can better define areas where tissues overlap. The use of contrast dyes for CT scan can further improve visualization in some areas, such as the digestive tract.

Fluoroscopy

This technique uses X-rays, but in real time, to create moving images of the body through the use of a fluoroscope. In its simplest form, a fluoroscope consisting of an X-ray source and a fluorescent screen between which a patient is placed, allows a physician to see the internal structure and function of a patient. This technique is used for both diagnosis and therapy and occurs in general radiology, interventional radiology, and image-guided surgery.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

This technique involves radio waves and magnetic fields to look at the organs and other structures in the body. The procedure requires an MRI scanner, which is, simply put, a large tube that contains a massive circular magnet. This magnet creates a powerful magnetic field that aligns the protons of hydrogen atoms in the body. Those protons are then exposed to radio waves, causing the protons to rotate. When the radio waves are turned off, the protons relax and realign themselves, emitting radio waves in the recovery process that can be detected by the machine to create an image.

Ultrasound (US)

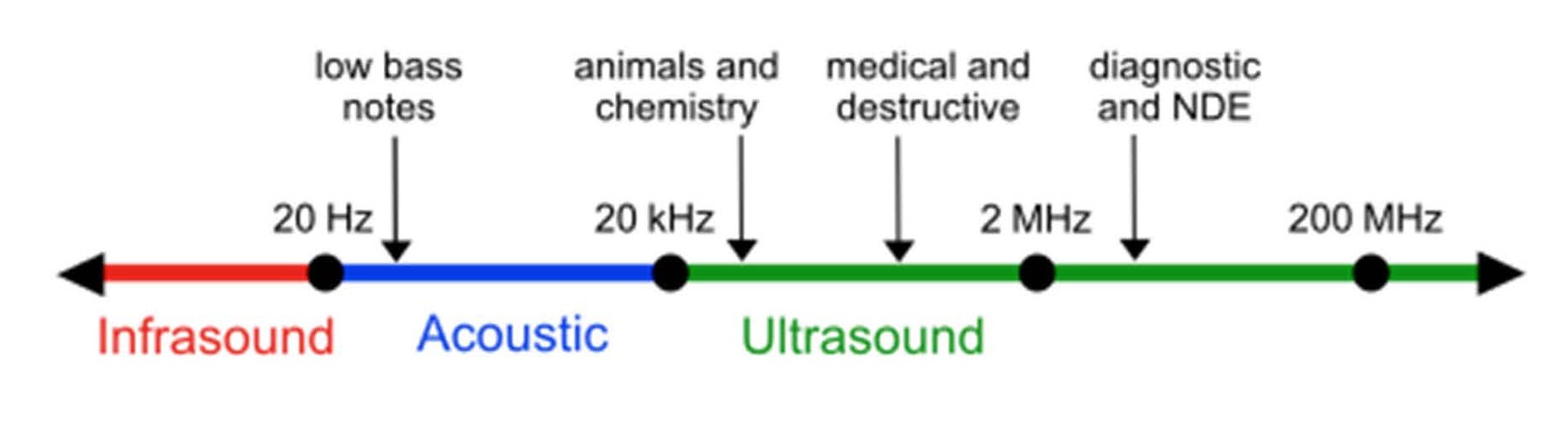

The usage of ultrasound to produce visual images for medicine is called medical ultrasonography or simply sonography (Figure 2) [5]. Sonography utilizes sound waves (acoustic energy) to produce moving images of organs, muscles, joints, and other soft tissues. Best known as a method for examining a fetus during pregnancy (obstetric sonography). Ultrasound does not involve radiation, and is therefore safe in pregnancy.

Figure 2. Approximate frequency ranges corresponding to ultrasound, with rough guide of some applications. NDE: Non-Destructive Examination.

Nuclear Medicine (NM)

This technique involves any medical use of radioactive materials like radioactive tracers that are injected or swallowed so that they can travel through the digestive or circulatory system. The radiation produced by the material can be detected via a camera in order to produce images of those systems. While most imaging methods are considered structural, these scans are used to evaluate how regions of the body function. Examples of nuclear medicine scans include positron emission tomography (PET) scan to record the radiation emitted for evaluating (a) presence of cancer metastases anywhere in the body using radioactive glucose or (b) causes of hyperthyroidism (thyroid scan) using radioactive iodine, etc.

Molecular Imaging (MI)

Molecular imaging is a field of medical imaging that focuses on imaging molecules of medical interest within living patients. The ultimate goal of molecular imaging is to be able to non-invasively monitor all of the biochemical processes occurring inside an organism in real time by using biomarkers that interact chemically with their surroundings and in turn alter the image according to molecular changes occurring within the area of interest. This ability to image fine molecular changes opens up an incredible number of exciting possibilities for medical application, including early detection and treatment of disease. Examples of MI include CT perfusion (CTP), dual-energy CT (DECT), and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT).

Conclusion

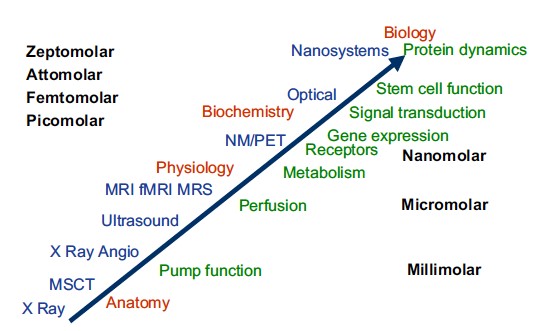

Each technique is used in different circumstances. For example, radiography is often used when we want image of bone structure to look for breakage. MRI scanners are often used to take images of the brain or other internal tissues, particularly when high-resolution images are needed. An advantage of MRI is that it does not use ionizing radiation, which has been linked to an increased risk of cancer, especially in children. Three limitations include the cost, body mass index (MRI is difficult in very overweight people), and that it may not be used in people who have metal in their body. Nuclear medicine is used when you need to look inside the digestive or circular systems, such as to look for blockages. Ultrasound is used to look at fetuses in the womb and to take images of internal organs when high resolution is not necessary. All of these techniques have been incredibility useful in medicine’s goal of saving lives and preventing suffering. Since X-rays and CT scans are forms of ionizing radiation (they knock electrons off atoms and can cause DNA damage), they may increase the risk of cancer. This is of greater concern with procedures such as CT or fluoroscopy than with plain X-rays, and more worrisome in children than in adults. With radiology procedures, it is important to weigh the risks and benefits of imaging and to consider possible alternatives when available. Relative sensitivity of imaging technologies is shown in Figure 3. The different interventional procedures can also carry risks, and it is important to discuss these with your healthcare provider.

Figure 3. Relative sensitivity of imaging technologies. PET and NM are the most sensitive clinical imaging technique. They have nanomole/kilogram sensitivity. X-rays systems including CT have millimole/kilogram sensitivity whereas MRI has about 10 mmole/kilogram sensitivity. CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; NM: Nuclear Medicine; PET: Positron Emission Tomography.

Perspective

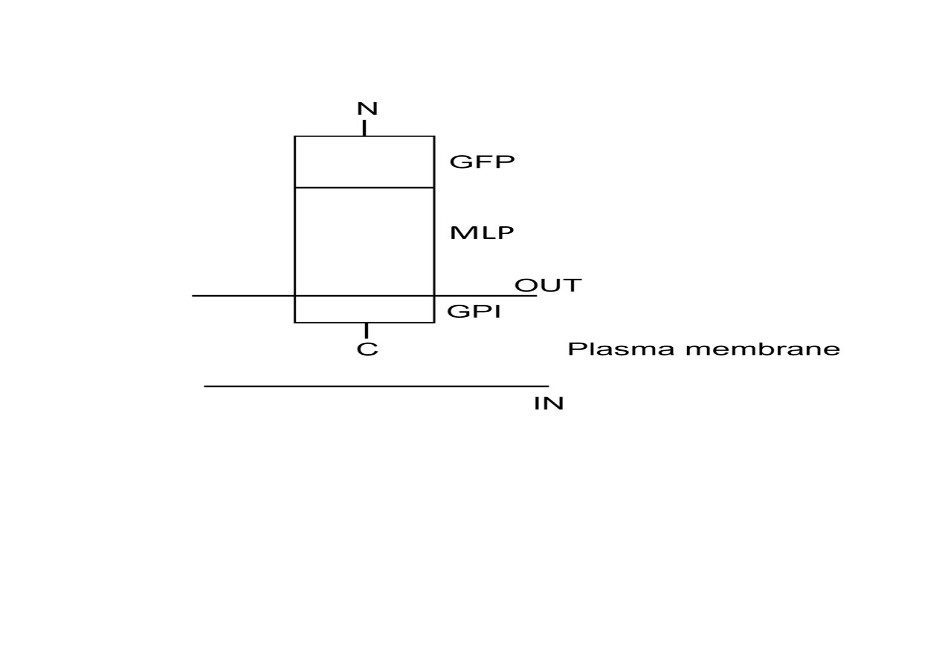

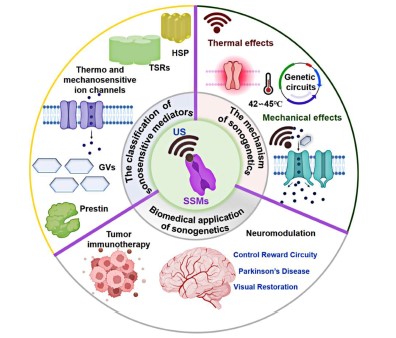

Studying biological function within the context of living organisms and the development of biomolecular and cellular therapy requires methods to imaging and control the function of specific molecules and cells in vivo such as optogenetics. This technique uses a combination of visible light and genetic engineering via changing the genetic information of a living thing (by inserting or deleting information in the genetic code) to control the activity of neurons or other cell types [6–8]. However, this technique has limited utility in deep tissues owing to the strong scattering of visible light [9]. In addition, while optogenetics allowed precise control of certain neurons, it still required a slightly invasive intervention (it requires brain surgery and leaves the patient with implanted fiber optic cables) [7,9]. Unlike photons, which are scattered within approximately one millimeter of tissue, US waves easily penetrate several centimeters deep while retaining spatial and temporal coherence. This capability has made US one of the world’s leading modalities for medical imaging of anatomy, physiology, and non-invasive therapy [5]. For example, application of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) for bone repair has been clinically approved [10,11]. Otherwise, the field of bioengineering has also made vast strides in improving the treatment of diseases and cancers [6]. The paring of these two technologies is known as sonogenetics: the non-invasive modulation of cellular function using bioengineering techniques to sensitize specific cells to US stimulation [12–19]. Sonogenetics is a new US approach that activates genetically encoded sonosensitive mediators (SSMs) in specific cell types, enabling the precise control of biomolecular functions with high spatiotemporal resolution. The mechanism of sonogenetics involves two components: US and SSMs [18]. The use of US waves in sonogenetics presents unique challenges, as this requires high spatial resolution and precise control of thermal and mechanical effects. To achieve desired sonogenetics effects while minimizing unintended tissue damage or adverse effects, precise adjustment of US parameters (e.g., frequency, intensity, duration, and waveform) is essential. Concerning SSMs, ideally, mediators should exhibit high sonosensitivity, enhance safety, and minimize tissue disruption during therapeutic procedures. It is crucial to determine which ones show both structural and functional compatibility with sonogenetics responsiveness. This issue is one of the main challenges in the development of non-invasive technologies such as sonogenetics: to find the appropriate sound-sensitive proteins as toolboxes. For such issues, the construction of expression vectors for any protein targeting to the cell plasma membrane via the glycosylphosphatidylinositol, GPI, anchor would be useful for studying intermolecular interactions and could be used as biomolecular tools for identifying sound-sensitive proteins as well as connecting directly ultrasound to modulate cellular functions such as gene expression and cellular signaling thereby enabling precise control. Such expression vectors can be performed as described previously for muscle LIM protein, MLP (which is believed to be involved in human heart failure) (Figure 4) for the potential treatment of heart failure via LIPUS [19]. Gene coding US-SSMs sensitive can be delivered to the target cells via gene delivery. This process is done with viral vectors and non-viral vectors methods and also the creation of transgenic lines. Viral vectors are commonly used to genetically modify specific cells. However, this approach raises safety and cost concerns due to the risk of viral vector leakage into non-targeted cells, potentially causing unintended side effects. Future research should combine new minimally invasive drug delivery techniques with SSMs-mediated sonogenetics in small and large animal models to achieve a precise, spatially targeting, and cell type-specific regulation of function and activity. In conclusion, sonogenetics uses both genetic engineering and US technology, representing a new avenue to control biomolecular function at the molecular level. Sonogenetics holds impressive potential in a wide range of applications, from tumor immunotherapy, and mitigation of Parkinsonian symptoms to the modulation of neural reward pathway, and restoration of vision, etc. (Figure 5) [18]. For example, this technology may be used to activate heart cells and insulin pumps: implanting SSMs in the human heart/pancreas and activating these cells with an external US device could revolutionize pacemakers and diabetes treatment. However, until now, like all emerging technologies, sonogenetics remains in the experimental stage and the translation to the clinic has been elusive because there are ongoing challenges that need to be addressed.

Figure 4. Schematic representation of the membrane topology of the expression vectors for muscle LIM protein (MLP). The mammalian expression vector pcDNATM 3.1 (+) is used as backbone in which all genes of interest are inserted in the right frame into the pcDNATM 3.1 (+) vector. The construct comprising the sequence encoding the C-terminal of the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol, GPI, anchor derived from the human folate receptor1 (FOLR1) protein; the entire coding sequence (CDS) of MLP gene coupled with the CDS of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene (Inspired from [19]).

Figure 5. Schematics design of the classification, generation, mechanism, and biomedical application of sonogenetics (Inspired from [18]. US: Ultrasound; SSMs: Sonosensitive Mediators; HSP: Heat Shock Promoter; TSRs: Temperature-Sensitive Repressors; GVs: Gas Vesicles; Prestin: an auditory-sensing protein found exclusively in outer cochlear hair cells. Prestin deficiency is associated with hearing loss in both humans and mice.

List of Abbreviations

CDS: Entire Coding Sequence; CT: Computed Tomography; CTP: Computed Tomography Perfusion; DECT: Dual-Energy Computed Tomography; FOLR1: Folate Receptor 1 protein; GFP: Green Fluorescent Protein; GPI: Glycosylphosphatidylinositol; LIPUS: Low-Intensity Pulsed Ultrasound; MI: Molecular Imaging; MLP: Muscle LIM Protein; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; NDE: Non-Destructive Examination; NM: Nuclear Medicine; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; SPECT: Single-Photon Emission Computed Tomography; SSMs: Sonosensitive Mediators; US: Ultrasound

Acknowledgments

The author did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Conflict of Interests

The author declares that there are no competing interests.

References

2. Radiation. The Free Dictionary by Farlex. Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 11 January 2014. Available from: http://www.thefreedictionary.com/radiation.

3. The Electromagnetic Spectrum. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015 Dec 7. Retrieved 29 August 2018. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/radiation-health/about/electromagnetic-spectrum.html.

4. Ng KH. Non-ionizing radiations—sources, biological effects, emissions and exposures. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Non-Ionizing Radiation at UNITEN (ICNIR2003): Electromagnetic Fields and Our Health; 2003 Oct 20–22.

5. Carson PL. Ultrasound: Imaging, development, application. Med Phys. 2023 Jun;50 Suppl 1:35–9.

6. Tamura R, Toda M. Historic Overview of Genetic Engineering Technologies for Human Gene Therapy. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2020 Oct 15;60(10):483–91.

7. Deisseroth K. Optogenetics: controlling the brain with light. Scientific American. 2010 Oct 20. Available from: http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=optogenetics-controlling.

8. Sahel JA, Boulanger-Scemama E, Pagot C, Arleo A, Galluppi F, Martel JN, et al. Partial recovery of visual function in a blind patient after optogenetic therapy. Nat Med. 2021 Jul;27(7):1223–9.

9. Durduran T, Choe R, Baker WB, Yodh AG. Diffuse Optics for Tissue Monitoring and Tomography. Rep Prog Phys. 2010 Jul;73(7):076701.

10. Harrison A, Lin S, Pounder N, Mikuni-Takagaki Y. Mode & mechanism of low intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) in fracture repair. Ultrasonics. 2016 Aug;70:45–52.

11. Harrison A, Alt V. Low-intensity pulsed ultrasound (LIPUS) for stimulation of bone healing - A narrative review. Injury. 2021 Jun;52 Suppl 2:S91–6.

12. Maresca D, Lakshmanan A, Abedi M, Bar-Zion A, Farhadi A, Lu GJ, et al. Biomolecular Ultrasound and Sonogenetics. Annu Rev Chem Biomol Eng. 2018 Jun 7;9:229–52.

13. Azadeh SS, Lordifard P, Soheilifar MH, Esmaeeli Djavid G, Keshmiri Neghab H. Ultrasound and Sonogenetics: A New Perspective for Controlling Cells with Sound. Iran J Pharm Res. 2021 Summer;20(3):151–60.

14. Duque M, Lee-Kubli CA, Tufail Y, Magaram U, Patel J, Chakraborty A, et al. Sonogenetic control of mammalian cells using exogenous Transient Receptor Potential A1 channels. Nat Commun. 2022 Feb 9;13(1):600.

15. Liu T, Choi MH, Zhu J, Zhu T, Yang J, Li N, et al. Sonogenetics: Recent advances and future directions. Brain Stimul. 2022 Sep-Oct;15(5):1308–17.

16. Liu P, Foiret J, Situ Y, Zhang N, Kare AJ, Wu B, et al. Sonogenetic control of multiplexed genome regulation and base editing. Nat Commun. 2023 Oct 18;14(1):6575.

17. Xian Q, Qiu Z, Murugappan S, Kala S, Wong KF, Li D, et al. Modulation of deep neural circuits with sonogenetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023 May 30;120(22):e2220575120.

18. Wu P, Liu Z, Tao W, Lai Y, Yang G, Yuan L. The principles and promising future of sonogenetics for precision medicine. Theranostics. 2024 Aug 12;14(12):4806–21.

19. Germain P, Grillon C, Nguyen KV. A narrative review of potential therapies for the treatment of myocardial tissue in relation to heart failure. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2025 Sep 1:1–29.