Abstract

Focused ultrasound has emerged as a key tool for neurologic disorders. In this focused review, we discuss the utility in disrupting the blood brain barrier to maximize treatment. This can facilitate creating direct coagulative lesions and aid in the administration of chemotherapy. Furthermore, it can facilitate neuromodulation when used in pulse sequencing. The current literature regarding brain tumors, essential tremor, and obsessive-compulsive disorder is reviewed. Additionally, concepts and experimental outcomes for neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s is presented. Focused ultrasound as a tool is still in its infancy but the potential for adjuvant and direct therapy is promising. More clinical uses will become apparent in coming decades.

Keywords

Focused ultrasound, Blood brain barrier, Brain tumors, Functional disorders, Neurodegeneration

Introduction

Focused ultrasound (FUS) uses curved transducers, lenses, and phased arrays to selectively target small areas and structures. The first FUS trials were conducted in the 1950s by Russell Meyers et al. to investigate its use in treating movement disorders, psychiatric disorders, and brain tumors [1]. This technology is also used in several other medical specialties for treatment of conditions including, but not limited to uterine fibroids, glaucoma, breast cancer, prostate cancer, and benign prostatic hypertrophy [2]. The literature on how the technology works and how it can be adapted to treat central nervous system pathology by means such as neuromodulation, thermoablation, and improved blood-brain barrier permeability is rapidly expanding [3].

Biological effects can occur through the intact skull with therapeutic FUS. Advances in the technology allow for minimally invasive use without the need for craniotomy or craniectomy unlike deep brain stimulation or thermal ablation [4,5]. FUS exerts its effects through focal temperature elevation, leading to tissue necrosis as the ultrasound is absorbed within the targeted tissue (Figure 1). Therefore, these treatments can be performed in a single session. While FUS is minimally invasive compared to other neuromodulation methods like deep brain stimulation, its effects are considered permanent [6,7].

Figure 1: Minimally invasive microsurgery is performed with FUS without use by creating small coagulative lesions. Created with BioRender.com.

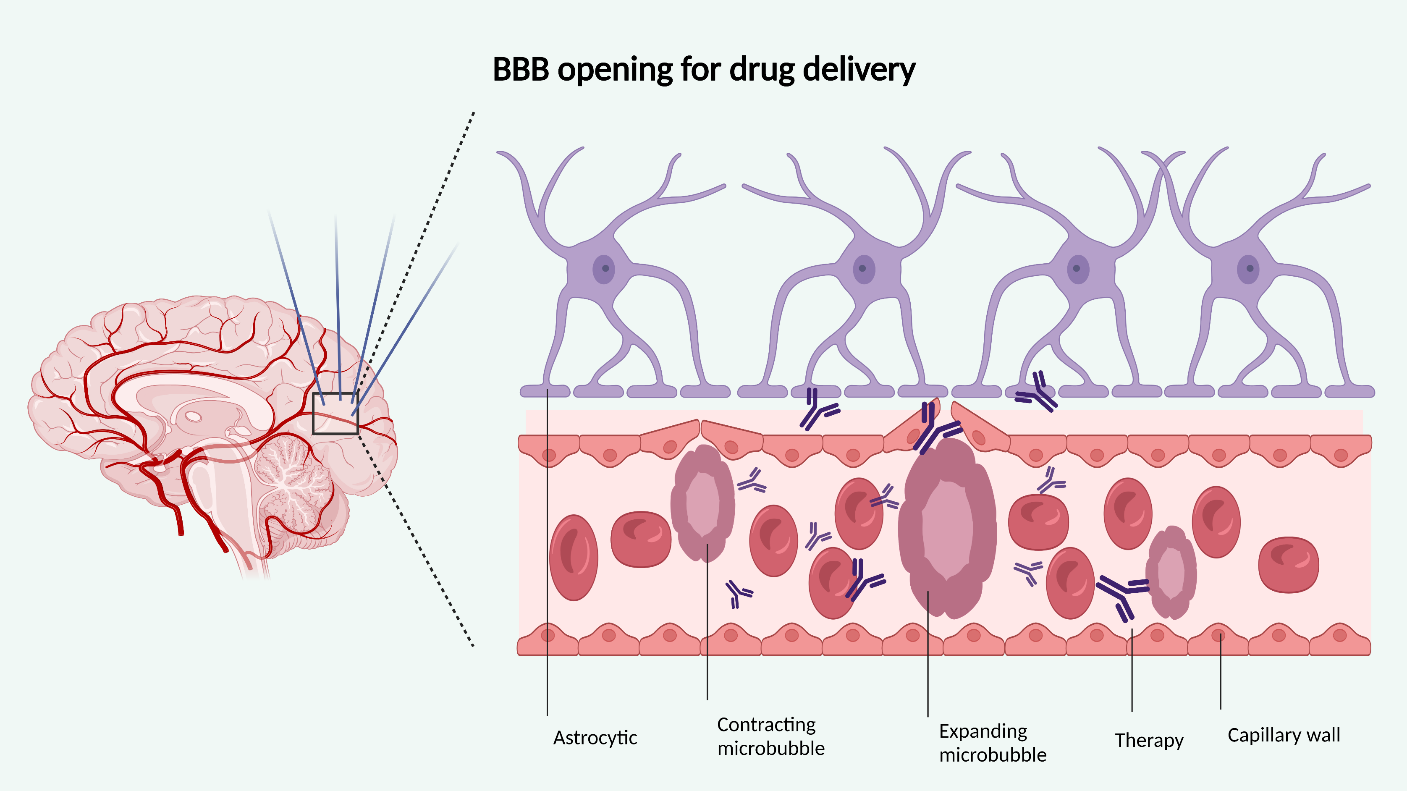

The blood-brain barrier (BBB) tightly controls and limits circulating molecules, including the transmission of therapeutic substances [8]. The BBB also regulates interstitial fluid composition, peripheral and central cellular signaling, immune function, and CNS homeostasis [9]. Its dysfunction is associated with several diseases such as multiple sclerosis (MS), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Alzheimer's disease (AD) [8]. FUS pressure waves cause cavitations and microbubble oscillations, which mechanically stress and increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier, increasing paracellular permeability by widening tight junctions and enhancing intracellular transport by upregulating cytoplasmic channels and vesicles (Figure 2) [10-15]. Therefore, increasing research has investigated the safety and efficacy of FUS in increasing CNS bioavailability of therapeutic agents and modulating the BBB in neurodegenerative disorders [16,17]. While temporary opening of the BBB has not shown major adverse effects in clinical trials, studies have shown that this opening alone can induce focal inflammation, Aβ clearance, and blood flow changes [18]. The degree to which these changes are beneficial or dangerous remain to be studied.

Figure 2: Cavitations and microbubbles created by FUS pressure waves transiently increase BBB therapeutic drug permeability. Created with

BioRender.com.

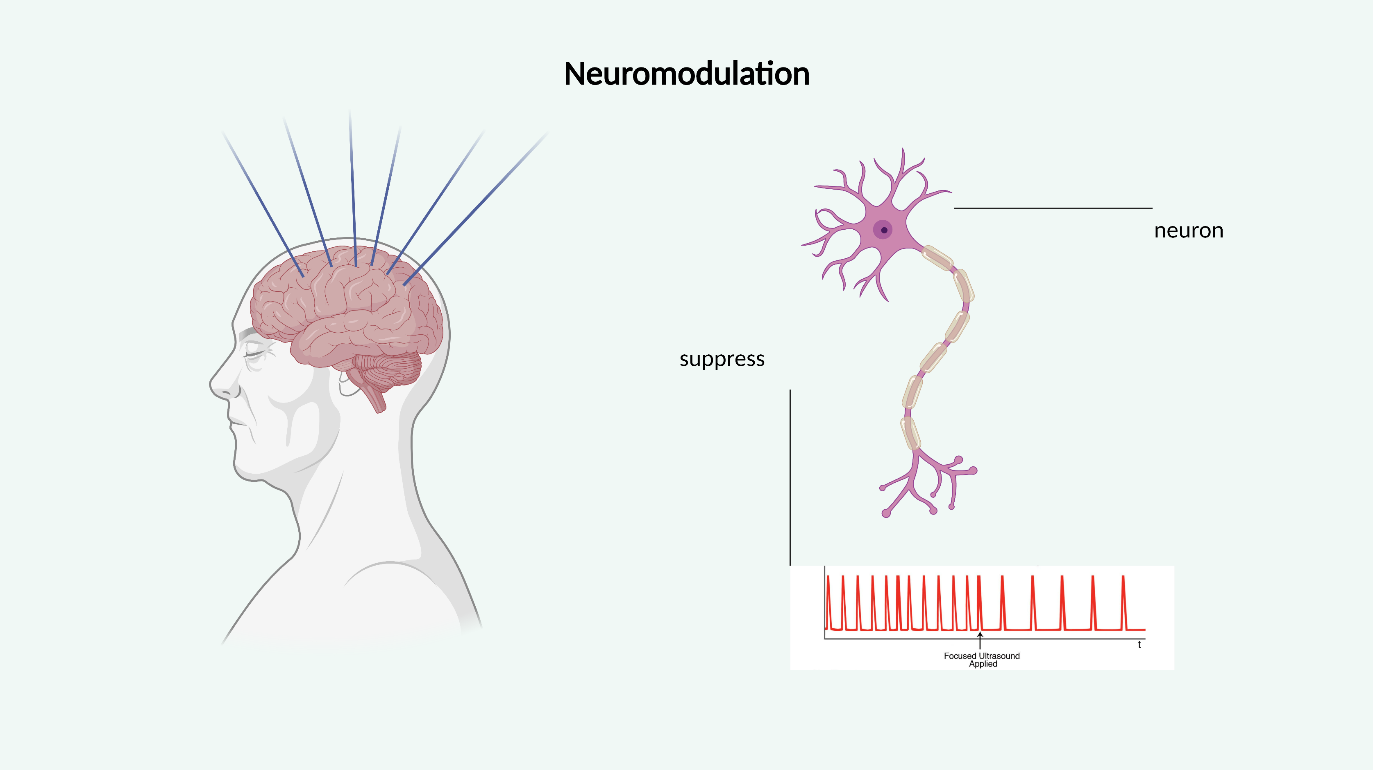

Neuromodulation by targeting structures like the hippocampus, thalamus, substantia nigra, motor cortex, putamen, and frontal lobe can be achieved by targeted sonication [19]. Techniques include inhibition by temporary hyperthermia and stimulation by activating membrane-bound mechanosensitive receptors and synaptic transmission (Figure 3) [20].

Figure 3: Noninvasive FUS can be used for neuromodulation of deep brain tissue neuromodulation in a spatially and temporally accurate manner.Created with BioRender.com.

Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) combines High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for targeting, treatment monitoring, and temperature mapping. MRgFUS uses synchronized high-intensity ultrasound emitters to create a lesion in a distinct area in a minimally invasive and stereotactic fashion. The total accumulated thermal dose predicts the lesion size [21,22]. During a session of MRgFUS treatment, the patient’s head is rigidly fixed onto a stereotactic frame that is coupled to an ultrasound (US) transducer following local anesthetic infiltration. The scalp is then inspected for scars or other compromisers of ultrasound passage. An elastic diaphragm filled with cool water is attached to the patient's scalp and connected to the ultrasound transducer [21,23]. The patient is then brought into the MRI, where the procedure will take place under image guidance. During a session of MRgFUS treatment, the area of interest is targeted stereotactically, and US energy is delivered in progressive doses through the intact skull until focal target temperatures and lesion size are achieved. The emitted ultrasound waves range between 200 kHz to 4 MHz frequencies based on their intended effects [24]. Temperature is monitored during the procedure using proton resonance frequency through MR thermometry. MR thermometry is important as there are temperature variations by location and amongst patients, likely secondary to ultrasound beam distortions from tissue layers [25,26]. The target can be confirmed by heating the region to ~ 48°C, which will reversibly inactivate tissue in this area. As the patient is awake, the effect on tremor is tested clinically, after which a definite, irreversible lesion can be placed by heating the region to 50°C [23,27]. Real-time thermal data feedback allows clinical teams to accurately adjust temperature and location parameters [28]. Treatment lasts 3-4 hours and will end once the team deems adequate clinical and radiological effects. A neurological examination will be performed after the procedure, and post-treatment MR images can be used to determine lesion location and size [21].

Many patients cannot undergo MRgFUS. Skull volume and density govern whether maximum temperature can be achieved in the deep brain. Adverse effects of providing adequate lesioning energy include skin lesions and local pain. However, these effects were partially mitigated by low frequencies, practical element sizes resulting in sharp focus with phased arrays, and phased array applicators with larger surface areas. Furthermore, a patient may elect not to undergo this procedure as it requires complete head shaving [23,27-32]. The procedure is contraindicated in patients with previous brain surgery as the brain parenchyma may receive more energy than predicted by software [21].

Focused ultrasound is in its infancy. Currently, there are relatively few institutions worldwide offering this type of therapy. Furthermore, institutions often offer these treatments as part of clinical trials do not yet perform commercial treatment [2]. However, this modality has promising potential in adjuvant and direct therapy. In this paper, we review the current use and literature of FUS in brain tumors, essential tremor, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and Alzheimer’s disease.

Brain Tumors

The blood-brain barrier is a network of vessels and tissues with proficient barrier properties and minimal transport vesicles [33]. The capillary endothelium creates tight junctions to restrict permeability and inhibit harmful substances from accessing the brain parenchyma [34]. The limited trans-cytoplasmic transport and formidable barrier, under normal conditions, would predominantly allow small, lipid-soluble therapeutics (<400 Da) to readily transport across the BBB via diffusion. However, most administered therapeutic agents are unable to penetrate as they are greater than 400-500 Da, severely restricting their bioavailability [34,35].

There has been increasing interest in enhanced delivery of chemotherapy drugs across the BBB as most modern systemic drugs have limited efficacy in the treatment of intracranial malignancies due to its highly selective permeability, often requiring near toxic chemotherapeutic agent doses to achieve a desired therapeutic effect [36,37]. Thus, there is increasing interest in the use of FUS with microbubbles to transiently disrupt the blood-brain barrier for enhanced transportation of drugs into the brain [38].

Doxorubicin is a chemotherapeutic drug that cannot appreciably cross the BBB but is otherwise effective against malignant gliomas. Preclinical studies have shown substantially improved doxorubicin delivery in liposomes to tumor cells sonicated with FUS technology [34,35,38].

Current methods to temporarily cause a micro disruption of the blood-brain barrier include the utilization of low-intensity (LIFU), high-intensity (HIFU), or MRgFUS. Transcranial transmittance of varying frequency ultrasound waves disrupt the BBB without damaging neighboring tissues by microbubble formation and oscillation [36,38]. This transient BBB disruption enhances the transportation of conventional chemotherapy drugs [24]. Cavitation and BBB disruption last roughly between 4-6 hours ensuring ample time for enhanced chemotherapeutic delivery [36]. There is no consensus on distinctive parameters for the application of FUS as each administration is contingent on the mechanism used (LIFU, HIFU, or MRgFUS); however, frequencies mainly used throughout preclinical trials fluctuated between 0.2-1.5 MHz, and acoustic pressures differed between 0.3-0.8 MPa [39,40].

Literature suggests implementing low-intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) as the safe and novel approach for transiently disrupting the BBB and warranting safe and sufficient delivery of chemotherapy drugs into tumors. This method entails the administration of low-frequency sound waves with simultaneously administered intravenous gas-filled microbubbles. The microbubbles sustain stable oscillations (stable cavitation) forcing a partition in cell junctions, an increase in vessel pressure to enable permeabilization, and an activation of cellular receptors and trans-cytoplasmic vesicles [40]. Furthermore, the employment of low-frequencies significantly diminishes the chance of permanent tissue damage. Low-intensity FUS has proved feasible in temporarily disrupting the blood-brain barrier and improving the delivery of enhanced chemotherapeutics into brain tumors (Figure 2).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is employed in conjunction to FUS as it provides the necessary guidance to target brain tumors and small functional structures accurately [24,33,36,37]. The utilization of specific sonication parameters, such as temperature, time, and intensity, facilitates safe, on-demand opening of the BBB. Diverse MRgFUS applications operated with temperatures ranging from 55-60?, frequencies ranging from 230-710 kHz, and sonication durations ranging from 10-30 seconds [33].

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) distributes high-energy ultrasound waves (100–10,000 W/cm2) at high temperatures (55?) to generate a thermal ablation at focal tumor regions [33,37]. For direct treatments, a transducer exerts ultrasonic energy (1-3 MHz) onto targeted tissue for localized destruction [41]. Furthermore, increased intensities of FUS instigates inertial oscillations of microbubbles, which can transiently cause the bubbles to collapse, damaging neighboring tissues and blood vessels [33,35]. HIFU was initially employed to circumvent the limitation of the BBB. However, such high frequencies may lead to unwanted tissue damage and hemorrhage [33,41]. Despite such risks, Yang et al. conveyed that repeated pulsed HIFU techniques can successfully deliver doxorubicin and other anticancer drugs to brain tumors [42].

Malignant glioma, a universally fatal brain tumor, is difficult to treat due to the drug-delivery limitations constituted by the BBB [38,42]. As a result of the expanding interest of FUS applications, Yang et al. applied repeated pulsed HIFU in a study that demonstrated the delivery and high concentration of AP-1 liposomal doxorubicin in glioma cells [42]. The animals investigated were treated with 5 mg/kg injections of AP-1 liposomal doxorubicin followed by repeated pulsed HIFU which sequentially exhibited significant accumulation of the enhanced drug at the sonicated site [42]. The study showed that minimal doses of liposomal doxorubicin treated with pulsed HIFU has the potential to penetrate a lipid insoluble barrier and reach a significant concentration in tumor cells.

The delivery of doxorubicin in the brain was also analyzed using MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Treat et al. investigated liposomal-encapsulated doxorubicin absorption in rat brain tumors employing MRgFUS to transiently and non-invasively disrupt the BBB [43]. The experiment used 0.6 W acoustic pressure at 30-second intervals to elicit a disruption of the BBB, allowing a substantial concentration of liposomal doxorubicin in tumor cells [43]. The literature reported that lower acoustic pressures and longer exposure times were crucial for optimal therapeutic drug uptake and minimal destruction of adjacent tissues. A similar analysis by Huang et al. used MRgFUS and a degassed chamber to explore BBB disruption and therapeutic drug intake. The results yielded increased BBB penetration with increased microbubble injections [44].

Clinical applications and data thus far have demonstrated the feasibility and efficacy of focused ultrasound mechanisms to induce micro disruptions in the blood-brain barrier to facilitate substantial absorption of enhanced chemotherapy drugs in brain tumors. FUS applications have generally proved safe in treating intracranial lesions in relation to other invasive methods (Table 1).

|

Study |

Reference |

|

Delivered liposomal-doxorubicin through the BBB using MRgFUS technique |

Treat et al. [43] |

|

Successfully transported AP-1 liposomal doxorubicin into glioma cells using high-intensity focused ultrasound |

Yang et al. [42] |

|

Disrupted the BBB using MRgFUS application and effectively transported methotrexate in a rabbit’s brain |

Mei et al. [141] |

|

Demonstrated feasibility of FUS disruption methods and delivered BCNU into glioblastoma tumors |

Liu et al. [142] |

While approved and useful for other clinical applications, the use of high-intensity MRIgFUS for thermal ablation of brain tumors was largely abandoned due to the inability to ablate large tumors in a short amount of time and the limited treatment envelope [45-47].

Essential Tremor

Per the International Parkinson’s and Movement Disorder Society, a tremor is defined as an “involuntary, rhythmic, oscillatory movement of a body part.” The distinguishing factor separating tremor from other hyperkinetic movement disorders is its rhythmicity. Tremors can be categorized into two axes. Axis 1 concentrates on the clinical features of the individual’s tremor and includes history, tremor characteristics at rest, posture, and action, associated signs, and additional laboratory tests to allow a syndromic approach for precise classification. Axis 2 classifies tremors based on their etiology, with essential tremor (ET) being one of the most common causes [27,48,49]. The definition and underlying pathophysiology of ET is still controversial. A consensus statement in 2018 defined ET as an isolated action tremor present in the bilateral upper extremities with or without a tremor in other locations for at least three years. Specifically, an isolated action means it is a kinetic or postural tremor without other neurologic symptoms sufficient that would point toward the diagnosis of another neurologic syndrome, like Parkinson’s disease, dystonia, cerebellar disease, or peripheral neuropathy. ET is one of the most common movement disorders in adults, affecting 1% of the population with greater than 60 million individuals worldwide. Its prevalence increases at least five times greater with advancing age, reaching up to 9% in patients 60 years or older affected with ET [27,48,50,51]. Older age also leads to faster disease progression. Increasing life expectancy has led to more patients presenting with essential tremor [50]. Still, its presence is seen widely throughout the age spectrum, with an average age of onset is 45 years [28,48].

The most significant risk factors for ET are genetic, though environmental factors are also suspected of contributing to changes in molecular, biochemical, and cellular components and oscillatory neuronal activity resulting in clinical tremors. While the pathophysiological mechanisms are not well understood, they likely involve the cerebellar-thalamic-cortical loop [27,52]. Post-mortem neuroimaging studies have demonstrated structural changes in the cerebellar Purkinje cells and neighboring neuronal populations, while others have revealed GABAergic dysregulation of the cerebellar-thalamic-cortical circuitry [51]. ET has an insidious onset. However, regardless of its progression, very few patients tend to reach significant disability. It does not decrease life expectancy, but can affect quality of life with psychosocial consequences, including depression, social isolation, and stigmatization [27,48,53,54]. ET often emerges in the arms as rhythmic oscillations between the agonist and antagonist muscles at frequencies between 8 Hz and 12 Hz. ET can also present as balance impairment and tremor of the voice, head, chin/jaw, or lower limbs.

The diagnostic workup for ET may include a complete medication history, brain imaging, and electromyography (EMG) [28]. Only education and reassurance are needed for uncomplicated cases. However, treatment is indicated when ET begins to affect daily activities or causes psychological distress [48]. First-line symptomatic treatment with oral agents is started after treatable etiologies are excluded [27,50]. Propranolol and primidone have level A evidence and successfully reduce tremor severity, allowing for better function with activities of daily living. Benefits from other agents are low if a patient’s symptoms have not responded to propranolol or primidone [48,55]. Neurosurgical intervention is considered for medically refractory cases of ET or when treatment side effects are unsatisfactory. Surgical intervention targets the thalamic ventralis intermedius nucleus (Vim) or the zona incerta in the posterior subthalamus. Both are a part of the tremor circuitry connecting the cerebellum with cortical motor pathways. The thalamic Vim has an inhibitory function in this network. The assumed mechanism is by activation of glutaminergic cerebello-thalamic and cortical-thalamic projections at high frequency, leading to synaptic fatigue at their terminals and subsequent inhibition of rhythmic activity that would lead to pathologic tremors [27,28,54]. The current surgical standard for medically refractory ET is DBS [48]. Magnetic Resonance-guided Focused Ultrasound (MRgFUS) is a relatively newer therapy that is less invasive than DBS [27,56,57]. Prospective trials on this newer non-invasive procedure have shown improvements in quality of life, greater than 80% hand tremor reductions, and minimal procedural morbidity. Such benefits have lasted at two-year follow-up, though recent FUS trials have shown a waning effect over the initial 12 post-treatment period [23,54,58].

Side effects from unilateral MRgFUS include paresthesias and imbalance. Bilateral MRgFUS side effects can include cognitive, gait, balance, and speech disturbances. Because the side effects are more pronounced and permanent after bilateral procedures compared to those that are unilateral, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved MRgFUS for the unilateral treatment of tremor [55,57]. The most common side effect is paresthesias involving the face, lips, or fingers secondary to accidental heating of the somatosensory thalamus. However, these adverse events can subside with time. A list of more adverse effects can be found in Table 2 [23,54]. Side effects may be mitigated by reduced treatment time, for which there is increased research. We hope for treatment times shorter than 30 minutes in the future [59,60]. Of note, the 2018 consensus classification for ET identified a new subgroup called ET plus, in which patients have associated subtle neurological ‘soft signs’, such as dystonic posturing, hearing loss, psychiatric disorders, and cognitive impairment, among many others. Because of this, ET plus may require a different treatment approach [50,55].

|

Thalamotomy |

Ultrasound Sonication |

Stereotactic Frame |

|

Paresthesia (Areas Include: face, hand, lips, tongue, fingers, leg) |

Nausea |

Periorbital edema |

|

Dysesthesia |

Emesis |

Headache |

|

Ataxia |

Syncope |

Scalp numbness in Occipital region |

|

Dysmetria |

Head Pain |

Pin-site laceration |

|

Slurred Speech |

Light-headedness |

|

OCD

The leading hypothesis for the neurophysiology of OCD is an overactivation of cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical (CSTC) connectivity loops. Notable regions within the CSTC pathophysiology of OCD include orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, anterior internal capsule, the basal ganglia, and the thalamus (Figure 4). Within the basal ganglia, the direct pathway is typically considered movement-activating, while the indirect pathway is typically thought to inhibit movement. Overactivation of CSTC loops is theorized to result in hyperactivity within the direct pathway resulting in impulsivity, repetitive behaviors, and impaired action inhibition observed in OCD patients [61].

Figure 4: Cortico-striatal-thalamo-cortical connectivity loops have been implicated in the pathophysiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Up to 60% of OCD patients do not respond to first-line drug therapies [62]. Historically, there has been a variety of neurosurgical interventions for patients with OCD, particularly among treatment-resistant patients. The initial surgical treatments for OCD involved cingulotomy and capsulotomy in the 1940s-1960s first with open and later with stereotactic techniques [63]. In the modern era, ablative procedures for OCD have evolved to include less invasive options such as radiofrequency ablation, stereotactic radiosurgery, laser interstitial thermal therapy, and deep brain stimulation (DBS) to achieve a reversible inhibitory effect [63]. Brain regions that have been targeted in open and stereotactic ablative procedures have included the cingulate gyrus, internal capsule, and subcaudate tract in limbic leucotomy [63]. Previously investigated DBS targets for OCD have included the anterior capsule, the area posterior-inferior to the anterior capsule, the ventral striatum, the nucleus accumbens, the subthalamic nucleus, and the inferior thalamic peduncle [64].

MRgFUS is another investigational treatment modality that has displayed promise for patients with OCD. Thus far, MRgFUS has been used for thermal ablation to perform capsulotomies. This was first used by Jung et al. in 2015 to perform bilateral capsulotomy on four patients with OCD, demonstrating a 33% mean improvement in the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) score at six months with no side effects [65]. At two years, patients had sustained improvements in Y-BOCS, HAM-D, and HAM-A scores with the only side effects being mild transient headache and vestibular symptoms [66]. Davidson et al. performed anterior capsule ablation in seven patients with OCD, showing improvement in the Y-BOCS, with the only side effect being mild transient headache and pin-site swelling [67]. MRgFUS for OCD has been reported to have a favorable side effect profile, even displaying an improvement in cognitive performance after intervention [68]. Two phase 1 clinical trials have been performed for MRgFUS capsulotomy in OCD, with 66% of patients achieving a clinical response [69], with two additional clinical trials pending publication (NCT01986296, NCT04775875; clinicaltrials.gov). Compared to alternative non-invasive ablation methods like stereotactic radiosurgery, MRgFUS may have a shorter interval to response and a potentially improved side effect profile compared to risks from radiation effects [70,71]. MRgFUS also has advantages of real-time monitoring with MR thermometry and may be more cost-effective than other methods such as radiofrequency ablation [71,72].

MRgFUS is an attractive option for OCD patients due to its ability to produce non-invasive, cost-effective ablations. To date, only capsulotomies have been explored using MRgFUS. One study identified specific areas within the dorsal anterior limb of the internal capsule that may be more efficacious for OCD [73]. Future studies can assess other locations along the CSTC circuit of OCD, including with the use of tractography, in addition to performing comparative studies between alternative lesioning methods and locations. Future studies can also assess patient-related outcome predictors for patient selection, such as skull parameters [74]. Additionally, studies thus far have only investigated HIFUS. Further research can help determine the utility of LIFUS in OCD such as for neuromodulation and blood-brain barrier disruption for drug delivery.

Alzheimer's Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia, with a prevalence of more than 1 in 9 Americans aged 65 and older. There is no cure for AD; it is currently the 6th leading cause of death in the US [75]. Focused ultrasound offers promise in the treatment of AD and has potential applications for improving drug delivery, Aß plaque reduction, promoting neurogenesis, and stimulating neural activity. Despite advances in therapies for AD, the impermeability of the blood-brain barrier remains an obstacle to effective drug development [11,12,76]. Focused ultrasound with microbubbles (FUS-MB) has been shown to transiently and safely increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier [11,77-79]. In conjunction with existing and future therapies, FUS-MB could allow for increased drug penetration and more targeted delivery, which may increase efficacy and decrease toxicity. One application under investigation is the combined administration of FUS-MB and intravenous immunotherapy. Compared to intravenous anti-ß-amyloid IgG (anti-Aß IgG) alone, combined FUS-MB and IV anti-Aß IgG showed significantly enhanced delivery to targeted brain regions and a significant reduction in the number, mean size, and surface area of ß-amyloid (Aß) plaques [12,15]. In a study of FUS-MB administered with IVIg targeting the bilateral hippocampus, mice receiving the combined treatment required a lower dose. They showed significantly increased hippocampal delivery of IVIg relative to mice receiving IVIg alone, which did not show significant blood-brain barrier crossing even at very high doses. In addition to the benefit of IVIg alone, which is the reduction of ß-amyloid pathology, IVIg following FUS-MB was associated with reduced TNF-a levels and enhanced neurogenesis in the hippocampus [80]. Application of FUS-MB to improve drug delivery is also being investigated with other treatments, including gene therapy, stem cells, neurotrophic factors, and other therapeutic agents [79-86]. FUS-MB utilizes a low-intensity ultrasound, below that which would result in thermal changes or tissue damage [78,87]. Potential risks of using FUS-MB to permeabilize the blood-brain barrier include red blood cell extravasation, damage to vascular tissue should microbubbles rapidly collapse, and edema in the targeted brain region [12,78,87]. However, with optimization of intensity, pressure, and microbubble resonance, it is possible to increase blood-brain barrier permeability with minimal tissue damage [78,87]. Furthermore, studies have shown that there is not a significant difference in the degree of blood-brain barrier permeabilization between mouse models of AD and control mice, which suggests that the degree of existing blood-brain barrier disruption intrinsic to some patients with AD is most likely not a variable [11,80].

Another application of focused ultrasound in the treatment of AD is the reduction of ß-amyloid plaques, which can be achieved using low-intensity focused ultrasound with microbubbles without the introduction of exogenous therapeutics. The reduction of ß-amyloid plaques is thought to occur via several mechanisms. The transient increase in blood-brain barrier permeability allows for the entry of endogenous IgG and IgM targeting ß-amyloid [88]. Anti-ß-amyloid antibodies then facilitate ß-amyloid clearance through solubilization of Aß, improved transport of Aß:antibody complexes, and opsonization of Aß for phagocytosis by microglia [88-94]. Low-intensity focused ultrasound with microbubbles also temporarily activates microglia and astrocytes in targeted areas [88,95]. Activated microglia and astrocytes phagocytose ß-amyloid, contributing to plaque reduction [88,95,96]. FUS-MB has been shown to modulate the expression of genes associated with the production and aggregation of ß-amyloid [96]. Although there is conflicting evidence regarding whether reduction of plaque size correlates with improved clinical symptoms or outcomes, studies have shown a correlation between ß-amyloid plaque reduction associated with FUS-MB and behavioral changes indicative of functional improvement in mouse models of AD [79,95].

Low-intensity focused ultrasound has also been shown to increase levels of several important neurotrophic factors and stimulate neurogenesis in targeted brain regions. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a key role in neurogenesis [97-99], neuroplasticity [99-102], synaptic activity [99,100,102] and memory [101-104]. Alzheimer’s disease is associated with reduced levels of BDNF in brain regions implicated in AD pathogenesis, which may contribute to disease progression [105-112]. Exogenous BDNF administration and BDNF gene therapy have been investigated as potential treatment strategies for AD. They have been shown in murine and primate models to reverse neuronal atrophy and synapse loss, improve cell signaling, partially correct aberrant gene expression, and improve cognition [113]. However, translating these studies into clinical therapies has been difficult due to challenges with safe and efficacious drug delivery [102,113-117]. As previously discussed, FUS-MB can be used to increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier in select regions of the brain, which, when followed by systemic administration of BDNF or BDNF gene therapy, would allow for targeted delivery [83,84]. Additionally, FUS-MB alone, without exogenous BDNF administration, has been shown to upregulate BDNF levels in targeted brain regions [99,115]. BDNF binds to TrkB receptors resulting in downstream upregulation of molecules involved in neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal activity [84,99]. FUS-MB also upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which promotes vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. AD is associated with reductions in neurovasculature, which is thought to decrease further the clearance of ß-amyloid and toxic metabolites from the brain. An increase in VEGF could thus aid with plaque reduction [46]. Furthermore, FUS-MB has been associated with upregulation of other mediators of neurogenesis including glial-derived neurotrophic factor [99], endothelial nitric oxide synthase [96], nerve growth factor [96], and basic fibroblast growth factor [118]. Together, these factors contribute to increased neuroplasticity and neurogenesis in targeted brain regions which are associated with behavioral changes indicative of cognitive improvement [79,99,119].

As research emerges supporting the efficacy of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in treating AD [120-127], focused ultrasound may present a promising alternative for patients who are not ideal surgical candidates or who prefer a less invasive approach. Low-intensity ultrasound can be used to non-invasively and reversibly modulate neuronal activity with high spatial resolution [128-135]. The ultrasound intensity used for neuromodulation is less than that required to cause temperature changes or brain damage [130,131,133,135]. The pulsed low-intensity ultrasound is delivered without microbubbles, preventing permeabilization of the blood-brain barrier [130,133]. Studies targeting the hippocampus with pulsed low-intensity ultrasound demonstrated evoked neural activity and network oscillation consistent with hippocampal circuit activation [130,131,135,136]. In a clinical pilot study investigating the use of pulsed low-intensity ultrasound in patients with AD, FUS resulted in increased neuronal activity in targeted regions of interest on functional MRI. In addition, this stimulation was associated with improvement of AD symptoms relevant to those brain regions, such as memory and verbal processing, whereas symptoms associated with nontargeted brain regions worsened likely due to the natural disease course. Notably, these improvements were maintained for at least three months post-stimulation with limited side effects and no brain hemorrhages or injury [131,137]. Initial work is promising, but further research is needed to evaluate pulsed low-intensity ultrasound as a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease [138].

Conclusion

In conclusion, focused ultrasound is a novel approach to treat brain tumors, essential tremor, OCD, and Alzheimer’s disease. It allows for minimally invasive tissue lesioning for neuromodulation. Furthermore, it is used to increase brain bioavailability for chemotherapeutic agents and biologic agents for brain neoplasms and neurodegenerative disorders by enhancing blood-brain barrier permeability. We look forward to research further assessing the appropriate use of focused ultrasound in these disease processes and novel preclinical studies assessing its use for other diseases, like the preclinical studies and clinical trials investigating the use of FUS for dissolution of clots from embolic strokes [139,140].

References

2. Foundation FU. Treatment Sites [Available from: https://www.fusfoundation.org/the-technology/treatment-sites/?indication=Brain%20Tumors%2C%20Glioma%20and%20Metastatic.

3. Aubry J-F, Pauly KB, Moonen C, Haar G, Ries M, Salomir R, et al. The road to clinical use of high-intensity focused ultrasound for liver cancer: technical and clinical consensus. J Ther Ultrasound. 2013;1(1):1-7.

4. Hynynen K, Jones RM. Image-guided ultrasound phased arrays are a disruptive technology for non-invasive therapy. Phys Med Biol. 2016;61(17):R206.

5. Ram Z, Cohen ZR, Harnof S, Tal S, Faibel M, Nass D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided, high-intensity focused ultrasound forbrain tumortherapy. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(5):949-56.

6. Mouratidis PX, Rivens I, Civale J, Symonds-Tayler R, Ter Haar G. Relationship between thermal dose and cell death for “rapid” ablative and “slow” hyperthermic heating. Int J Hyperthermia. 2019;36(1):229-243.

7. ter Haar G, Coussios C. High intensity focused ultrasound: physical principles and devices. Int J Hyperthermia. 2007;23(2):89-104.

8. Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV. Blood–brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(3):133-50.

9. Galea I, Bechmann I, Perry VH. What is immune privilege (not)? Trends Immunol. 2007;28(1):12-8.

10. Kovacs ZI, Kim S, Jikaria N, Qureshi F, Milo B, Lewis BK, et al. Disrupting the blood–brain barrier by focused ultrasound induces sterile inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(1):E75-E84.

11. Burgess A, Hynynen K. Drug delivery across the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(5):711-21.

12. Raymond SB, Treat LH, Dewey JD, McDannold NJ, Hynynen K, Bacskai BJ. Ultrasound enhanced delivery of molecular imaging and therapeutic agents in Alzheimer's disease mouse models. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(5):e2175.

13. Sheikov N, McDannold N, Sharma S, Hynynen K. Effect of focused ultrasound applied with an ultrasound contrast agent on the tight junctional integrity of the brain microvascular endothelium. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34(7):1093-104.

14. Sheikov N, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Cellular mechanisms of the blood-brain barrier opening induced by ultrasound in presence of microbubbles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2004;30(7):979-89.

15. Jordão JF, Ayala-Grosso CA, Markham K, Huang Y, Chopra R, McLaurin J, et al. Antibodies targeted to the brain with image-guided focused ultrasound reduces amyloid-beta plaque load in the TgCRND8 mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(5):e10549.

16. Van Tellingen O, Yetkin-Arik B, De Gooijer M, Wesseling P, Wurdinger T, De Vries H. Overcoming the blood–brain tumor barrier for effective glioblastoma treatment. Drug Resist Updat. 2015;19:1-12.

17. Meng Y, Pople CB, Lea-Banks H, Abrahao A, Davidson B, Suppiah S, et al. Safety and efficacy of focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening, an integrative review of animal and human studies. J Control Release. 2019;309:25-36.

18. Todd N, Angolano C, Ferran C, Devor A, Borsook D, McDannold N. Secondary effects on brain physiology caused by focused ultrasound-mediated disruption of the blood-brain barrier. J Control Release. 2020;324:450-9.

19. Lipsman N, Meng Y, Bethune AJ, Huang Y, Lam B, Masellis M, et al. Blood–brain barrier opening in Alzheimer’s disease using MR-guided focused ultrasound. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1-8.

20. Dallapiazza RF, Timbie KF, Holmberg S, Gatesman J, Lopes MB, Price RJ, et al. Noninvasive neuromodulation and thalamic mapping with low-intensity focused ultrasound. J Neurosurg. 2017;128(3):875-84.

21. Rohani M, Fasano A. Focused Ultrasound for Essential Tremor: Review of the Evidence and Discussion of Current Hurdles. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2017;7:462.

22. Huang Y, Lipsman N, Schwartz ML, Krishna V, Sammartino F, Lozano AM, et al. Predicting lesion size by accumulated thermal dose in MR-guided focused ultrasound for essential tremor. Med Phys. 2018;45(10):4704-10.

23. Dallapiazza RF, Lee DJ, De Vloo P, Fomenko A, Hamani C, Hodaie M, et al. Outcomes from stereotactic surgery for essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(4):474-82.

24. Harary M, Segar DJ, Huang KT, Tafel IJ, Valdes PA, Cosgrove GR. Focused ultrasound in neurosurgery: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(2):E2.

25. McDannold N, Tempany CM, Fennessy FM, So MJ, Rybicki FJ, Stewart EA, et al. Uterine leiomyomas: MR imaging-based thermometry and thermal dosimetry during focused ultrasound thermal ablation. Radiology. 2006;240(1):263-72.

26. Liu HL, McDannold N, Hynynen K. Focal beam distortion and treatment planning in abdominal focused ultrasound surgery. Med Phys. 2005;32(5):1270-80.

27. Hopfner F, Deuschl G. Managing Essential Tremor. Neurotherapeutics. 2020;17(4):1603-21.

28. Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound Neurosurgery for Essential Tremor: A Health Technology Assessment. Ont Health Technol Assess Ser. 2018;18(4):1-141.

29. Hynynen K, Jolesz FA. Demonstration of potential noninvasive ultrasound brain therapy through an intact skull. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1998;24(2):275-83.

30. Sun J, Hynynen K. Focusing of therapeutic ultrasound through a human skull: a numerical study. J Acoust Soc Am. 1998;104(3 Pt 1):1705-15.

31. Sun J, Hynynen K. The potential of transskull ultrasound therapy and surgery using the maximum available skull surface area. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;105(4):2519-27.

32. Clement GT, Sun J, Giesecke T, Hynynen K. A hemisphere array for non-invasive ultrasound brain therapy and surgery. Phys Med Biol. 2000;45(12):3707-19.

33. Lee EJ, Fomenko A, Lozano AM. Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound : Current Status and Future Perspectives in Thermal Ablation and Blood-Brain Barrier Opening. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2019;62(1):10-26.

34. Alekou T, Giannakou M, Damianou C. Focused ultrasound phantom model for blood brain barrier disruption. Ultrasonics. 2021;110:106244.

35. Pandit R, Chen L, Götz J. The blood-brain barrier: Physiology and strategies for drug delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;165-166:1-14.

36. Alli S, Figueiredo CA, Golbourn B, Sabha N, Wu MY, Bondoc A, et al. Brainstem blood brain barrier disruption using focused ultrasound: A demonstration of feasibility and enhanced doxorubicin delivery. J Control Release. 2018;281:29-41.

37. Arsiwala TA, Sprowls SA, Blethen KE, Adkins CE, Saralkar PA, Fladeland RA, et al. Ultrasound-mediated disruption of the blood tumor barrier for improved therapeutic delivery. Neoplasia. 2021;23(7):676-91.

38. Etame AB, Diaz RJ, Smith CA, Mainprize TG, Hynynen K, Rutka JT. Focused ultrasound disruption of the blood-brain barrier: a new frontier for therapeutic delivery in molecular neurooncology. Neurosurg Focus. 2012;32(1):E3.

39. Han M, Hur Y, Hwang J, Park J. Biological effects of blood-brain barrier disruption using a focused ultrasound. Biomed Eng Lett. 2017;7(2):115-20.

40. McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Hynynen K. Blood-brain barrier disruption induced by focused ultrasound and circulating preformed microbubbles appears to be characterized by the mechanical index. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008;34(5):834-40.

41. Quadri SA, Waqas M, Khan I, Khan MA, Suriya SS, Farooqui M, et al. High-intensity focused ultrasound: past, present, and future in neurosurgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2018;44(2):E16.

42. Yang FY, Teng MC, Lu M, Liang HF, Lee YR, Yen CC, et al. Treating glioblastoma multiforme with selective high-dose liposomal doxorubicin chemotherapy induced by repeated focused ultrasound. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:965-74.

43. Treat LH, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Zhang Y, Tam K, Hynynen K. Targeted delivery of doxorubicin to the rat brain at therapeutic levels using MRI-guided focused ultrasound. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(4):901-7.

44. Huang Y, Hynynen K. MR-guided focused ultrasound for brain ablation and blood-brain barrier disruption. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;711:579-93.

45. McDannold N, Clement GT, Black P, Jolesz F, Hynynen K. Transcranial magnetic resonance imaging- guided focused ultrasound surgery of brain tumors: initial findings in 3 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(2):323-32; discussion 32.

46. Ram Z, Cohen ZR, Harnof S, Tal S, Faibel M, Nass D, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided, high-intensity focused ultrasound for brain tumor therapy. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(5):949-55; discussion 55-6.

47. Coluccia D, Fandino J, Schwyzer L, O'Gorman R, Remonda L, Anon J, et al. First noninvasive thermal ablation of a brain tumor with MR-guided focused ultrasound. J Ther Ultrasound. 2014;2:17.

48. Reich SG. Essential Tremor. Med Clin North Am. 2019;103(2):351-6.

49. Tarakad A, Jankovic J. Essential Tremor and Parkinson's Disease: Exploring the Relationship. Tremor Other Hyperkinet Mov (N Y). 2018;8:589.

50. Shanker V. Essential tremor: diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2019;366:l4485.

51. Welton T, Cardoso F, Carr JA, Chan LL, Deuschl G, Jankovic J, et al. Essential tremor. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021;7(1):83.

52. Hopfner F, Deuschl G. Is essential tremor a single entity? Eur J Neurol. 2018;25(1):71-82.

53. Langford BE, Ridley CJA, Beale RC, Caseby SCL, Marsh WJ, Richard L. Focused Ultrasound Thalamotomy and Other Interventions for Medication-Refractory Essential Tremor: An Indirect Comparison of Short-Term Impact on Health-Related Quality of Life. Value Health. 2018;21(10):1168-75.

54. Elias WJ, Lipsman N, Ondo WG, Ghanouni P, Kim YG, Lee W, et al. A Randomized Trial of Focused Ultrasound Thalamotomy for Essential Tremor. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):730-9.

55. Sharma S, Pandey S. Treatment of essential tremor: current status. Postgrad Med J. 2020;96(1132):84-93.

56. Ferreira JJ, Mestre TA, Lyons KE, Benito-León J, Tan EK, Abbruzzese G, et al. MDS evidence-based review of treatments for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2019;34(7):950-8.

57. Iorio-Morin C, Hodaie M, Lozano AM. Adoption of focused ultrasound thalamotomy for essential tremor: why so much fuss about FUS? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(5):549-54.

58. Elble RJ, Shih L, Cozzens JW. Surgical treatments for essential tremor. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018;18(4):303-21.

59. Yiannakou M, Trimikliniotis M, Yiallouras C, Damianou C. Evaluation of focused ultrasound algorithms: Issues for reducing pre-focal heating and treatment time. Ultrasonics. 2016;65:145-53.

60. Ebbini ES, Ter Haar G. Ultrasound-guided therapeutic focused ultrasound: Current status and future directions. Int J Hyperthermia. 2015;31(2):77-89.

61. Calzà J, Gürsel DA, Schmitz-Koep B, Bremer B, Reinholz L, Berberich G, et al. Altered Cortico-Striatal Functional Connectivity During Resting State in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:319.

62. Pallanti S, Hollander E, Bienstock C, Koran L, Leckman J, Marazziti D, et al. Treatment non-response in OCD: methodological issues and operational definitions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(2):181-91.

63. Jung HH, Chang WS, Kim SJ, Kim CH, Chang JW. The Potential Usefulness of Magnetic Resonance Guided Focused Ultrasound for Obsessive Compulsive Disorders. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2018;61(4):427-33.

64. Holtzheimer PE, Mayberg HS. Deep brain stimulation for psychiatric disorders. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:289-307.

65. Jung HH, Kim SJ, Roh D, Chang JG, Chang WS, Kweon EJ, et al. Bilateral thermal capsulotomy with MR-guided focused ultrasound for patients with treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: a proof-of-concept study. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20(10):1205-11.

66. Kim SJ, Roh D, Jung HH, Chang WS, Kim CH, Chang JW. A study of novel bilateral thermal capsulotomy with focused ultrasound for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: 2-year follow-up. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2018;43(4):170188.

67. Davidson B, Hamani C, Huang Y, Jones RM, Meng Y, Giacobbe P, et al. Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound Capsulotomy for Treatment-Resistant Psychiatric Disorders. Oper Neurosurg (Hagerstown). 2020;19(6):741-9.

68. Davidson B, Hamani C, Meng Y, Baskaran A, Sharma S, Abrahao A, et al. Examining cognitive change in magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound capsulotomy for psychiatric illness. Transl Psychiatry. 2020 Nov 11;10(1):1-0.

69. Davidson B, Hamani C, Rabin JS, Goubran M, Meng Y, Huang Y, et al. Magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound capsulotomy for refractory obsessive compulsive disorder and major depressive disorder: clinical and imaging results from two phase I trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25(9):1946-57.

70. Mustroph ML, Cosgrove GR, Williams ZM. The Evolution of Modern Ablative Surgery for the Treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive and Major Depression Disorders. Front Integr Neurosci. 2022;16:797533.

71. Chang KW, Jung HH, Chang JW. Magnetic Resonance-Guided Focused Ultrasound Surgery for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders: Potential for use as a Novel Ablative Surgical Technique. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:640832.

72. Kumar KK, Bhati MT, Ravikumar VK, Ghanouni P, Stein SC, Halpern CH. MR-Guided Focused Ultrasound Versus Radiofrequency Capsulotomy for Treatment-Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Cost-Effectiveness Threshold Analysis. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:66.

73. Germann J, Elias GJB, Neudorfer C, Boutet A, Chow CT, Wong EHY, et al. Potential optimization of focused ultrasound capsulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. Brain. 2021;144(11):3529-40.

74. Davidson B, Mithani K, Huang Y, Jones RM, Goubran M, Meng Y, et al. Technical and radiographic considerations for magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound capsulotomy. J Neurosurg. 2020:1-9.

75. 2021 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2021;17(3):327-406.

76. Pardridge WM. The blood-brain barrier: bottleneck in brain drug development. NeuroRx. 2005;2(1):3-14.

77. Hynynen K, McDannold N, Vykhodtseva N, Jolesz FA. Noninvasive MR imaging-guided focal opening of the blood-brain barrier in rabbits. Radiology. 2001;220(3):640-6.

78. McDannold N, Arvanitis CD, Vykhodtseva N, Livingstone MS. Temporary disruption of the blood-brain barrier by use of ultrasound and microbubbles: safety and efficacy evaluation in rhesus macaques. Cancer Res. 2012;72(14):3652-63.

79. Burgess A, Dubey S, Yeung S, Hough O, Eterman N, Aubert I, et al. Alzheimer disease in a mouse model: MR imaging-guided focused ultrasound targeted to the hippocampus opens the blood-brain barrier and improves pathologic abnormalities and behavior. Radiology. 2014;273(3):736-45.

80. Dubey S, Heinen S, Krantic S, McLaurin J, Branch DR, Hynynen K, et al. Clinically approved IVIg delivered to the hippocampus with focused ultrasound promotes neurogenesis in a model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(51):32691-700.

81. Burgess A, Ayala-Grosso CA, Ganguly M, Jordão JF, Aubert I, Hynynen K. Targeted delivery of neural stem cells to the brain using MRI-guided focused ultrasound to disrupt the blood-brain barrier. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(11):e27877.

82. Wang F, Wei X-X, Chang L-S, Dong L, Wang Y-L, Li N-N. Ultrasound combined with microbubbles loading BDNF retrovirus to open bloodbrain barrier for treatment of alzheimer's disease. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:615104.

83. Wang F, Shi Y, Lu L, Liu L, Cai Y, Zheng H, et al. Targeted delivery of GDNF through the blood-brain barrier by MRI-guided focused ultrasound. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(12):e52925.

84. Baseri B, Choi JJ, Deffieux T, Samiotaki G, Tung Y-S, Olumolade O, et al. Activation of signaling pathways following localized delivery of systemically administered neurotrophic factors across the blood-brain barrier using focused ultrasound and microbubbles. Phys Med Biol. 2012;57(7):N65-81.

85. Hsu P-H, Lin Y-T, Chung Y-H, Lin K-J, Yang L-Y, Yen T-C, et al. Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening Enhances GSK-3 Inhibitor Delivery for Amyloid-Beta Plaque Reduction. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):12882.

86. Xhima K, Markham-Coultes K, Kofoed RH, Saragovi HU, Hynynen K, Aubert I. Ultrasound delivery of a TrkA agonist confers neuroprotection to Alzheimer-associated pathologies. Brain. 2021. Dec 17;awab460.

87. Meng Y, Pople CB, Lea-Banks H, Abrahao A, Davidson B, Suppiah S, et al. Safety and efficacy of focused ultrasound induced blood-brain barrier opening, an integrative review of animal and human studies. J Control Release. 2019;309:25-36.

88. Jordão JF, Thévenot E, Markham-Coultes K, Scarcelli T, Weng Y-Q, Xhima K, et al. Amyloid-β plaque reduction, endogenous antibody delivery and glial activation by brain-targeted, transcranial focused ultrasound. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:16-29.

89. Wilcock DM, DiCarlo G, Henderson D, Jackson J, Clarke K, Ugen KE, et al. Intracranially administered anti-Abeta antibodies reduce beta-amyloid deposition by mechanisms both independent of and associated with microglial activation. J Neurosci. 2003;23(9):3745-51.

90. Wilcock DM, Rojiani A, Rosenthal A, Levkowitz G, Subbarao S, Alamed J, et al. Passive amyloid immunotherapy clears amyloid and transiently activates microglia in a transgenic mouse model of amyloid deposition. J Neurosci. 2004;24(27):6144-51.

91. Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, LaRue B, Guo H, et al. IgG-assisted age-dependent clearance of Alzheimer's amyloid beta peptide by the blood-brain barrier neonatal Fc receptor. J Neurosci. 2005;25(50):11495-503.

92. Solomon B, Koppel R, Frankel D, Hanan-Aharon E. Disaggregation of Alzheimer beta-amyloid by site-directed mAb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(8):4109-12.

93. McLaurin J, Cecal R, Kierstead ME, Tian X, Phinney AL, Manea M, et al. Therapeutically effective antibodies against amyloid-beta peptide target amyloid-beta residues 4-10 and inhibit cytotoxicity and fibrillogenesis. Nat Med. 2002;8(11):1263-9.

94. Bard F, Cannon C, Barbour R, Burke RL, Games D, Grajeda H, et al. Peripherally administered antibodies against amyloid beta-peptide enter the central nervous system and reduce pathology in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):916-9.

95. Leinenga G, Götz J. Scanning ultrasound removes amyloid-β and restores memory in an Alzheimer's disease mouse model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(278):278ra33.

96. Eguchi K, Shindo T, Ito K, Ogata T, Kurosawa R, Kagaya Y, et al. Whole-brain low-intensity pulsed ultrasound therapy markedly improves cognitive dysfunctions in mouse models of dementia - Crucial roles of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Brain Stimulat. 2018;11(5):959-73.

97. Waterhouse EG, An JJ, Orefice LL, Baydyuk M, Liao G-Y, Zheng K, et al. BDNF promotes differentiation and maturation of adult-born neurons through GABAergic transmission. J Neurosci. 2012;32(41):14318-30.

98. Scharfman H, Goodman J, Macleod A, Phani S, Antonelli C, Croll S. Increased neurogenesis and the ectopic granule cells after intrahippocampal BDNF infusion in adult rats. Exp Neurol. 2005;192(2):348-56.

99. Shin J, Kong C, Lee J, Choi BY, Sim J, Koh CS, et al. Focused ultrasound-induced blood-brain barrier opening improves adult hippocampal neurogenesis and cognitive function in a cholinergic degeneration dementia rat model. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2019;11(1):110.

100. Monteggia LM, Barrot M, Powell CM, Berton O, Galanis V, Gemelli T, et al. Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(29):10827-32.

101. Bramham CR, Messaoudi E. BDNF function in adult synaptic plasticity: the synaptic consolidation hypothesis. Prog Neurobiol. 2005;76(2):99-125.

102. Lu B, Nagappan G, Guan X, Nathan PJ, Wren P. BDNF-based synaptic repair as a disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2013;14(6):401-16.

103. Bekinschtein P, Cammarota M, Katche C, Slipczuk L, Rossato JI, Goldin A, et al. BDNF is essential to promote persistence of long-term memory storage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2711-6.

104. Kaplan DR, Miller FD. Neurotrophin signal transduction in the nervous system. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2000;10(3):381-91.

105. Zuccato C, Cattaneo E. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5(6):311-22.

106. Phillips HS, Hains JM, Armanini M, Laramee GR, Johnson SA, Winslow JW. BDNF mRNA is decreased in the hippocampus of individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Neuron. 1991;7(5):695-702.

107. Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63(1):71-124.

108. Tapia-Arancibia L, Aliaga E, Silhol M, Arancibia S. New insights into brain BDNF function in normal aging and Alzheimer disease. Brain Res Rev. 2008;59(1):201-20.

109. Murer MG, Boissiere F, Yan Q, Hunot S, Villares J, Faucheux B, et al. An immunohistochemical study of the distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the adult human brain, with particular reference to Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience. 1999;88(4):1015-32.

110. Narisawa-Saito M, Wakabayashi K, Tsuji S, Takahashi H, Nawa H. Regional specificity of alterations in NGF, BDNF and NT-3 levels in Alzheimer's disease. Neuroreport. 1996;7(18):2925-8.

111. Peng S, Wuu J, Mufson EJ, Fahnestock M. Precursor form of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor are decreased in the pre-clinical stages of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2005;93(6):1412-21.

112. Lee J, Fukumoto H, Orne J, Klucken J, Raju S, Vanderburg CR, et al. Decreased levels of BDNF protein in Alzheimer temporal cortex are independent of BDNF polymorphisms. Exp Neurol. 2005;194(1):91-6.

113. Nagahara AH, Merrill DA, Coppola G, Tsukada S, Schroeder BE, Shaked GM, et al. Neuroprotective effects of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in rodent and primate models of Alzheimer's disease. Nat Med. 2009;15(3):331-7.

114. Thoenen H, Sendtner M. Neurotrophins: from enthusiastic expectations through sobering experiences to rational therapeutic approaches. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5 Suppl:1046-50.

115. Lin W-T, Chen R-C, Lu W-W, Liu S-H, Yang F-Y. Protective effects of low-intensity pulsed ultrasound on aluminum-induced cerebral damage in Alzheimer's disease rat model. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9671.

116. Pardridge WM. Blood-brain barrier delivery. Drug Discov Today. 2007;12(1-2):54-61.

117. Binder DK, Croll SD, Gall CM, Scharfman HE. BDNF and epilepsy: too much of a good thing? Trends Neurosci. 2001;24(1):47-53.

118. Reher P, Doan N, Bradnock B, Meghji S, Harris M. Effect of ultrasound on the production of IL-8, basic FGF and VEGF. Cytokine. 1999;11(6):416-23.

119. Scarcelli T, Jordão JF, O'Reilly MA, Ellens N, Hynynen K, Aubert I. Stimulation of hippocampal neurogenesis by transcranial focused ultrasound and microbubbles in adult mice. Brain Stimulat. 2014;7(2):304-7.

120. Laxton AW, Tang-Wai DF, McAndrews MP, Zumsteg D, Wennberg R, Keren R, et al. A phase I trial of deep brain stimulation of memory circuits in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):521-34.

121. Lozano AM, Fosdick L, Chakravarty MM, Leoutsakos J-M, Munro C, Oh E, et al. A phase II study of fornix deep brain stimulation in mild alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(2):777-87.

122. Oishi K, Lyketsos CG. Alzheimer's disease and the fornix. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:241.

123. Luo Y, Sun Y, Tian X, Zheng X, Wang X, Li W, et al. Deep brain stimulation for alzheimer's disease: stimulation parameters and potential mechanisms of action. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:619543.

124. Lyketsos CG, Targum SD, Pendergrass JC, Lozano AM. Deep brain stimulation: a novel strategy for treating Alzheimer's disease. Innov Clin Neurosci.9(11-12):10-7.

125. Smith GS, Laxton AW, Tang-Wai DF, McAndrews MP, Diaconescu AO, Workman CI, et al. Increased cerebral metabolism after 1 year of deep brain stimulation in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(9):1141-8.

126. Hamani C, Stone SS, Garten A, Lozano AM, Winocur G. Memory rescue and enhanced neurogenesis following electrical stimulation of the anterior thalamus in rats treated with corticosterone. Exp Neurol. 2011;232(1):100-4.

127. Hamani C, McAndrews MP, Cohn M, Oh M, Zumsteg D, Shapiro CM, et al. Memory enhancement induced by hypothalamic/fornix deep brain stimulation. Ann Neurol. 2008;63(1):119-23.

128. Naor O, Krupa S, Shoham S. Ultrasonic neuromodulation. J Neural Eng. 2016;13(3):031003.

129. Verhagen L, Gallea C, Folloni D, Constans C, Jensen DE, Ahnine H, et al. Offline impact of transcranial focused ultrasound on cortical activation in primates. Elife. 2019 Feb 12;8:e40541. .

130. Tufail Y, Matyushov A, Baldwin N, Tauchmann ML, Georges J, Yoshihiro A, et al. Transcranial pulsed ultrasound stimulates intact brain circuits. Neuron. 2010;66(5):681-94.

131. Beisteiner R, Matt E, Fan C, Baldysiak H, Schönfeld M, Philippi Novak T, et al. Transcranial Pulse Stimulation with Ultrasound in Alzheimer's Disease-A New Navigated Focal Brain Therapy. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2020;7(3):1902583.

132. Legon W, Bansal P, Tyshynsky R, Ai L, Mueller JK. Transcranial focused ultrasound neuromodulation of the human primary motor cortex. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):10007.

133. Yoo S-S, Bystritsky A, Lee J-H, Zhang Y, Fischer K, Min B-K, et al. Focused ultrasound modulates region-specific brain activity. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):1267-75.

134. Tyler WJ, Tufail Y, Finsterwald M, Tauchmann ML, Olson EJ, Majestic C. Remote excitation of neuronal circuits using low-intensity, low-frequency ultrasound. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(10):e3511.

135. Rinaldi PC, Jones JP, Reines F, Price LR. Modification by focused ultrasound pulses of electrically evoked responses from an in vitro hippocampal preparation. Brain Res. 1991;558(1):36-42.

136. Yuan Y, Yan J, Ma Z, Li X. Noninvasive Focused Ultrasound Stimulation Can Modulate Phase-Amplitude Coupling between Neuronal Oscillations in the Rat Hippocampus. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:348.

137. Dörl G, Matt E, Beisteiner R. Functional Specificity of TPS Brain Stimulation Effects in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease: A Follow-up fMRI Analysis. Neurol Ther. 2022. May 28:1-8.

138. Tramontin NDS, Silveira PCL, Tietbohl LTW, Pereira BDC, Simon K, Muller AP. Effects of Low-Intensity Transcranial Pulsed Ultrasound Treatment in a Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2021;47(9):2646-56.

139. Burgess A, Huang Y, Waspe AC, Ganguly M, Goertz DE, Hynynen K. High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) for dissolution of clots in a rabbit model of embolic stroke. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(8):e42311.

140. Zafar A, Quadri SA, Farooqui M, Ortega-Gutiérrez S, Hariri OR, Zulfiqar M, et al. MRI-Guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound as an Emerging Therapy for Stroke: A Review. J Neuroimaging. 2019;29(1):5-13.

141. Mei J, Cheng Y, Song Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Liu Y, et al. Experimental study on targeted methotrexate delivery to the rabbit brain via magnetic resonance imaging-guided focused ultrasound. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28(7):871-80.

142. Liu HL, Hua MY, Chen PY, Chu PC, Pan CH, Yang HW, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption with focused ultrasound enhances delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs for glioblastoma treatment. Radiology. 2010;255(2):415-425.