Abstract

This paper interprets subjective psychological time in a model of consciousness called the HLbC model proposed by the authors. Time has an objective physical time and a subjective psychological time. Subjective psychological time is thought to vary in its flow depending on the individual and the situation. For this explanation, this paper introduces surreal numbers into the perception of subjective psychological time. A surreal number is a number determined from two sets of different magnitudes and contains various temporal features, including the second law of thermodynamics. By this introduction, it is shown that subjective psychological cognition is reduced to the information entropy of the present and the past by the individual or the state of each individual and depends on the state of the information entropy.

Keywords

Mathematical model, Human language, Time, psychological time, Surreal number

Introduction

Time is a concept that encompasses physical time (absolute time), psychological time, astronomical time, physiological time, and biological time. Along with the understanding of consciousness, that understanding is one of the greatest challenges. Aristotle defined time as having nothing to do with the motion of a planet, but with numbers before and after the motion, the order in which things occur before and after. Next, Newton defined "absolute space" in terms of spatial coordinates as the basis for his kinematics, and "absolute time" as time that flows uniformly in this space, unaffected by nothing. This concept was rejected by Einstein and replaced by "The way time passes is not constant and varies from observer to observer depending on the speed at which the observers pass each other (relative speed)" in his theory of special relativity. Thus, the concept of time in physics has changed, and in recent years, Carlo Rovelli has made the case in his writings that time does not exist [1]. This nonexistence of time has long been developed by McTaggard and others, primarily as a philosophical question [2].

Time is also deeply connected to our consciousness, and to understand consciousness is to understand time. Two kinds of time are thought to exist in our cognitive world. One is objective physical time, and the other is subjective psychological time. In daily life, objective time is the norm, and for everyone 10 minutes is exactly 10 minutes. On the other hand, in everyone, the conscious flow of time is subjectively transitioned, and even though there is a divergence from objective time, it is a psychological reality. That is, psychological time is the internal experience of how quickly time passes or how much time passes since the occurrence of an event [3]. This flow of psychological time is not uniform - for example, in the same objective time, but in subjective time, it feels shorter when focused on things and longer when bored. The interpretation of differences arising in such subjective time flows has long been tried. Perhaps, Pieron H is known as the first person to postulate a physiological tempo or internal clock [4]. He hypothesized that raising or lowering body temperature would increase or decrease the passage of subjective time. In addition, models that assume physiological tempo and internal clock explain the relationship between biological components such as body temperature, pulse and respiration and psychological time that may be related to physiological tempo and internal clock, such as Scalar expectation theory (SET) model [5] and Attentional-Gate model [6,7].

Janet’s law is based on the idea that "the length of time we feel in a certain period of our life is proportional to the inverse of our age" and was invented by Janet P [8]. In other words, as we get older, the proportion of the "year" in our life decreases, so we begin to feel that the year is shorter, and time passes faster. Namely, a rule of thumb concerning psychological time. For example, if the year we felt at the age of one is 1/1, the year we felt at the age of two is 1/2, meaning we feel twice as fast as we did at the age of one. Furthermore, as the denominator age increases, from 1/5 at age 5, which is five times that of 1 year, to 1/10 at age 10, the proportion of one year in one's life decreases, and time feels shorter. Psychological time is thought to have a particularly strong element of consciousness, and its correct interpretation is: How does consciousness perceive time? It can also lead to an understanding of the nature of.

Allen's interval-based theory is a theory of the representation of time proposed by David Allen. The theory views time as intervals and specifies how these intervals relate to each other. Specifically, it defines the relationship between intervals, such as whether different intervals overlap each other or whether one encompasses the other. By explaining the representation of time in terms of simple, intuitive relationships, Allen has provided a model that facilitates our everyday understanding and communication of time. It is highlighted in the context of the summary how this theory relates to other models of time and that the paper proposes a new approach in an inclusive way [9,10].

The authors propose that there is a common sensory knowledge that people share in their everyday dealings with the world, and that there is a universality that enables cooperation and communication with the world and defend it in two different ways. Specifically, they present an axiomatization of time based on intervals and the single relation "MEET", which they show encompasses Allen's interval-based theory. It also formally defines the beginning and end of intervals and shows that these have properties that should normally be associated with points. It distinguishes between these point-like objects and the notion of moments hypothesized in discrete-time models, ultimately testing the theory on the basis of several different models [11].

Lachlan Kent and Marc Wittmann emphasize the importance of temporal consciousness in their model of consciousness [12]. They state that many theories of consciousness only refer to brief, static, discrete 'functional moments'. In their article, they highlight a review by Northoff and Lamme, in which they discuss eight main theories of consciousness ((i.e. integrated information theory [13-16], global neuronal workspace theory [GNWT], predictive coding theory [PCT], recurrent processing theory [RPT], embodied theory [ET], synchrony theory [ST], higher-order thought theory [HOT], and temporospatial theory [TTC]) are reviewed and the authors present a comparison of each theory and its engagement with time [17]. Their review states that major theories such as IIT, GNWT, RPT and ST are concerned with narrow timescales between approximately 100-300 (ms); GNWT, RPT and ST have methodological limitations; and PCT and PCT are concerned with the nature of time and the nature of the time scale. Thus, although the consciousness model should be related to the nature of time, we believe that it is still essentially unresolved. If existing models of consciousness assume a specific time range, it implies that consciousness has a hierarchical structure dependent on time. However, the authors posit that time is created by consciousness itself and considering that the "cognition" of time constitutes or influences consciousness may be putting the cart before the horse. Therefore, this paper advances the discussion from the perspective of how consciousness recognizes "time."

In previous reports, the author has proposed the HLbC model as a model for understanding consciousness [18]. In the second reports, we applied it to psychological consciousness and showed that it can answer certain themes of psychological consciousness such as Rubin's vase [19]. This paper builds on the concept of the HLbC model and examines how consciousness perceives time. Among them, the existing findings to be used are summarized below.

Overview of the HLbC Model of Consciousness in Human Languages

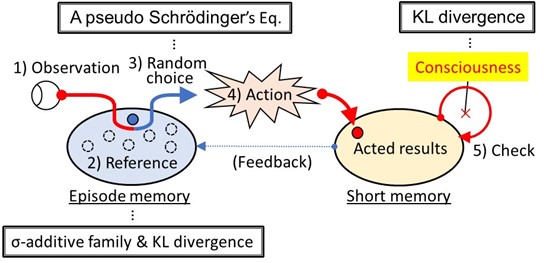

An overview of the HLbC model is shown in Figure 1. Assume that the proposed model consists of the following six steps from observation to awareness.

Figure 1. Overview of the HLbC model concept and associated mathematics.

1) Observation

This is the observation of external events through our senses.

2) Reference

The HLbC model assumes that episodic memories store observed memories in the form of sentences or images, which are then associated with emotions. This emotional association gives episodic memory a different meaning to the same sentence 'there is a big dog running'. Thus, for an observed event, episodic memory associates the emotion with the sentence or image, and the behavior of the event is stored in multiple memories.

3) Random choice

The brain randomly and unconsciously selects the next action from these multiple episodic memories and associated action memories. Randomness depends on physical factors such as the connections between neurons in the brain and the number of neurotransmitters.

4) Action

From the random selection in 4) above, an action is taken as a response to a random observation.

5) Storage of acted results to Short-term memory

The action described in 5) above is stored in short-term memory.

6) Check of acted results in Short-term memory-consciousness

The results of the action in Short-term memory are re-recognized by oneself - this moment is elicited when consciousness is born.

In summary, the moment when, based on observation, we randomly and unconsciously select an action and belatedly recognize the action is the moment of the birth of consciousness. These processes can also be defined mathematically as follows (see Figure 1 for the relationship between each STEP).

a) Episodic memory of sentences or images linked to emotions as a direct product of probability spaces.

Everyone has different qualia for different events. A probability space is defined for the qualia of each observed event, and a common 'word' for the observed event can be defined when the Kullback-Leibler distance [20], calculated as the probability density in each probability space, is the same. Furthermore, individual languages are defined as sentences as the direct product of probability spaces. Furthermore, an episodic memory is defined as the direct product of the defined probability space of sentences with the probability space of emotions.

b) Random selection of actions from episodic memory.

This process can be formulated by the Fokker-Planck equation as a purely probabilistic process. Conclusively, it can be shown from this mathematical model that the random process is equivalent to the pseudo-Schrodinger equation. In other words, the process of consciousness can be said to behave in a quantum way, albeit only as an analogy.

c) Consciousness as a post-episode recognition of the action.

This awareness recognizes the consistency between the past episodic memory of the action and the random behavioral outcome. This 'recognition' is the state in which the value of the Kalbach-Leibler distance between the probability density in the probability space of the past episodic memory and the probability density of the current action is zero.

The above is an overview of the HLbC model proposed by the authors. The Kullback-Leibler distance used above has been found to be equivalent to information entropy. In the following time recognition model, information entropy is considered instead of Kullback-Leibler distance.

Modeling Time Recognition by Consciousness

Based on the above HLbC model, time recognition is considered in each STEP of 1) to 6) in Figure 1.

1) Observation

This can be thought of as comparing one's own memories of the present with those of the past.

2) Reference

This is the process of referring to memories of one's time.

3) Random choice

For example, it is a sensory choice such as 10 seconds elapsed in reference to a memory when counting time by oneself.

4) Action

It is the determination of the estimated result of how much time has elapsed.

5) Storage of acted results to Short-term memory, and 6) check of acted results in Short-term memory-consciousness

It recognizes the actual time by comparison with a device that measures time quantitatively, such as a clock. If it is shorter than the mechanically measured 10 seconds, it is recognized as a passage of a shorter psychological time, while if it is longer than 10 seconds, it is regarded as a long psychological time.

Thus, the process of time cognition is also understandable in the HLbC model. However, this is a qualitative understanding of time perception and does not account for differences in psychological time felt by individuals. The model from which this difference arises is constructed below. We make various cognitions based on information acquired through the five senses. So, what are the internal organs that recognize time? We are faced with the question:. Time is based on consciousness and can be thought of as the recognition that the "present consciousness" gains by comparing the "past consciousness." In other words, the observation of "consciousness itself" by "consciousness." Based on this, we consider a model of time recognition by consciousness. It is important to note here that it is essential to consider the following in the perception of time:

1) containing or defined from the second law of thermodynamics

2) It should be determined by the consciousness or information of the individual observer and not merely by time as an order.

It is not possible to assess differences in psychological time felt by individuals unless 2) is included.

The second law of thermodynamics

The second law of thermodynamics is the law of the direction in which heat moves and of entropy. The second law of thermodynamics is expressed using entropy, in short:. If the entire system is isolated or insulated from the outside, the following inequalities arise during the transition from state A to state B.

SB ?SA 1)

Or, using the difference, ΔS,

ΔS?0 2)

The above expression represents that "In the adiabatic state (isolated state), the state changes such that the entropy of the system is constant or increases.". As is well known, this second law of thermodynamics is the only relationship in physics that tells us that the flow of time has a direction, whereas the equations of motion in mechanics are generally symmetric with respect to time reversal. In consciousness, how to incorporate this law in discussing time should be key.

Modeling primal time by Consciousness

As discussed in the previous section, the passage of time should ideally be explained by the second law of thermodynamics. In this context, it is essential to relate the increase in a system's entropy to a single "numerical value" termed "time." To the best of the authors' knowledge, no existing physical or mathematical theoretical framework addresses this perspective. Therefore, this paper employs the "surreal numbers" defined by Conway as a model of time, providing a mathematical framework in which "a single numerical value can be defined based on the increase or magnitude of two quantities." The surreal number is simply the number x determined by comparing the two sets XL, XR defined below [21-24].

x=XL, XR where, XL≥XR

Here, we understand the nature between the elements of the aggregate XL, XR, where XL≥XR . That is, the components of XL are larger or at most the same as any components of XR. This definition can yield an infinitely "new" number after defining zero, as follows:

Now, set: XL, XR is given an empty set φ. Since an empty set has no elements, it is safe to apply it to Eq. 3). The number defined in that case is "0." That is,

0=φ,φ 4)

Then, using the newly obtained 0, we apply the set of elements only of 0 to Eq. 3) to define 1 below.

1=0,φ 5)

In the same operation, infinitely new numbers can be made from new numbers, new sets containing them as elements. The characteristic of surreal numbers is that any number, including real numbers and infinity, can be generated by this operation.

In the HLbC model proposed by the author, past episodic memory stored in the brain plays an important role. Over time, new experiences, past episodic memory based on recognition, change constantly. The information entropy H can be defined from a probability density function consisting of elements of past episodic memory. Let the information entropy of the past episodic memory be, for example, HA for the value of A time, and HP for the value of "present" through time relative to A time. Then, from the second law of thermodynamics by Eq. 2):

HP?HA 6)

should be satisfied. We apply this Hp, HA to the above surreal number Eq. 6). We can then define a surreal number T that satisfies:

? T=HP, HA where, Hp≥HA

7)

This means that one "number" T can be defined from the law of entropy increase in the second law of thermodynamics. The second law of thermodynamics is the law of the direction of time, and the surreal number ΔT defined in Eq. 7) can be interpreted as an indicator of the direction of time. In Eq. 7), in a situation where there is no consciousness at all - for example, at the moment of “birth” - there is no past episodic memory, in which case HP = HA =φ, and from Eq. 4), time begins. In this way, by defining time as a surreal number, we think we were able to define "time" as an indicator of the "flow of time" from the second law of thermodynamics.

A surreal number defined as above is a closed system of addition and subtraction that secures the properties that time should have. That is, the following two theorems hold:

[Theorem 1]

If x and y are any surreal number, then only one of

xy holds. 8)

[Theorem 2]

Zero is a surreal number. If x is a surreal number, then -x is also a surreal number. If x and y are surreal numbers, then the following is true, and x + y is also a surreal number.

x+y=y+x, x+0=x, x+-x=0 9)

x≤y ↔ x+z≤y+z 10)

Furthermore, the product and quotient of surreal numbers can also be defined, but since we believe that only addition and subtraction is sufficient in the discussion of time, we will omit them.

In addition, in the case of surreal numbers, the following comparison rules are established. That is, for x= (XL, XR), y=(YL, YR), the following holds:

?There is no xL ∈ XL such that y ≤ xL. (Every element in the left part of x is strictly smaller than y).

?There is no yR ∈ YR such that yR ≤ x. (Every element in the right part of y is strictly larger than x).

Thus, the surreal number is determined from the second law of thermodynamics, which holds between the past and the present two information entropies and includes the satisfactory nature of time.

What is important here is not the introduction of surreal numbers, but the existence of a mechanism to determine one number from past and present episodic memory and the second law of thermodynamics. Therefore, it doesn't have to be a surreal number. We don't have an organ to measure time, directly. But consciousness uses past episodic memory to feel a difference from the present episode - this is what we think of as the essence of time. In addition to surreal numbers, the difference between past and present episodes and the second law of thermodynamics suggests that a framework for giving numbers can exist. A more rational mathematical framework may be found in the future. The second law of thermodynamics, on the other hand, is the rule of thumb. Time as a "quantity" determined by that rule of thumb may not be a physical quantity. It should be added that there are reports that Iyoda E et al. proved it from the viewpoint of quantum mechanics [25].

This is the most basic time generated from consciousness, and we call it "primal time" or "subjective time." This time T can be said to be a comparison between past and present episodic memory, a time that depends on individuals introspecting their own consciousness. Next, consider a more objective and quantitative time.

Modeling "Objective time" by consciousness

The "primal time T", as defined in the previous section, can also be called "subjective time," and although the order is considered, there is no specific quantifiability such as universality, one second, or two seconds for that time. Quantification is achieved by comparing the primal time felt in introspection with changes in devices - clocks, etc. - that are permanently quantifiable. For example, when counting 10 seconds, few people can accurately count 10 seconds. Then, by counting and checking each second on our watch, we can obtain accurate time quantifiability. The time acquired in this way is called "Objective time." Interpreting this common time acquisition from the point of view of the HLbC model is an operation that minimizes the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the probability space of one's perceived primal time and that of the time-measured data by the device, which is deterministic. Therefore, the HLbC model is not inconsistent with the definition of primal time defined above. When humans were conscious of the accuracy of time, they first used night and day, seasonal changes, or, as times progressed, pulse, etc. Indeed, when Galileo Galilei discovered the periodicity of the pendulum, he is said to have measured it with a pulse.

Modeling 'Common time' through consciousness

In the section “Modeling primal time by Consciousness”, we discussed individual quantitative 'Objective time'. Next, if the Kullback-Leibler divergence between the probability spaces of an individual's "Objective time" is zero, then we have a “common time” independent of the individual objective time. This is the same as replacing the qualia felt by individuals, which was discussed in the first report, with an official language to create “commonality”. According to the definition in the sections “The second law of thermodynamics” and “Modeling primal time by Consciousness” above, the time that consciousness perceives can be treated equally with color, etc.

We believe that the process described in sections “Modeling primal time by consciousness,” “Modeling " Objective time" by consciousness,” and “Modeling 'Common time' through consciousness” correctly defines the definition of time as we experience it daily.

Comparing "Objective time" and "Common time" with time according to existing definitions

Here, we compare the definitions of "objective time" and "common time" defined earlier with the existing definitions of time. Einstein A, in his theory of special relativity, describes the definition of static time [26], so for the sake of comparison, this paper first quotes it verbatim below. However, the distinction between STEP-1 and STEP -2 was made by the author.

?STEP-1?

By replacing "time" with the position of the hour hand on the clock, it becomes possible to overcome all the difficulties in the definition of "time." And in fact, such a definition would succeed if it tried to define time only about the position of the clock.

But it is no longer successful if it is necessary to connect a sequence of events that occur in different places to time, or to assess the time of events that occur in the same place but away from the clock. So, in line with the next train of thought, we consider practical decisions.

?STEP-2?

If there is a clock at point A in space, the observer at point A can know the time of an event in its immediate vicinity by finding the simultaneous location of the event and the hand. If there is another clock at point B in space that is similar in every way to that at point A, the observer at B can determine the time value of an event in the immediate vicinity of B. However, without further hypotheses, no comparison can be made regarding time between events at location A and those at location B. Up to this point, we have only defined "A time" and "B time" and not "time" in Human with A and B. The latter is not defined until we "by definition" establish that the "time" required for the travel of light from A to B is equal to the "time" required from B to A. Suppose that at "A time" tA a ray from A starts toward B, is reflected by B in the direction of A at "B time" tB, and arrives at t'A at "A time" again at A. Two clocks are defined to synchronize when:

tA-tB=t'A-tB 11)

We assume that this definition is irrefutable and can be applied to any number of points; And suppose that the following relationship always holds place independent:

1) If the clock in B synchronizes with the clock in A, the clock in A synchronizes with the clock in B.

2) If the clock in A is synchronized with the clock in B, and with the clock in C, the clocks in B and C are synchronized with each other.

The "time" of an event is: The event and the clock located at the location of the event are given at the same time, and this clock is synchronized with a particular stationary clock, certainly synchronized during all time determinations. According to experience, we further assume the following quantities:

2ABt'A-tA=c 12)

This is the universal constant: the speed of light in a vacuum. It is essential to have a time defined by means of a stationary clock in a stationary system, and a time properly defined in a stationary system is called the "time of a stationary system."

The static time defined by Einstein in STEP -1 above is the individual's "Objective time" in the paper, while the time in STEP -2 is "objective time." Therefore, the definition of time by the definition in this paper can be said to be synonymous with the existing definition of time. A comparison of the values of Kullback-Leibler divergence is characterized by the introduction of awareness, which quantitatively measures the degree of agreement of "common time”.

Discussions

The following discussion is based on the time defined by the HLbC model.

About the past and future

In the above discussion, time is defined based on a comparison of episodic memories of the "present" and the "past." As such, there are no indicators referring to the "future.". So, from the definition of time advocated by this paper, what are the "past" and "future"? to discuss.

"Past"

In the framework of this paper, the "past" remains as episodic memory as individual "subjective/objective time" or exists only in the memory of "history" as "common time." There would be no such thing as a "past world" stored anywhere.

"Future"

From the above discussion, nothing can be said about the "future world”. At present, the question of "Does the future exist somewhere?" is unanswerable to this theory. In the framework of this paper, there are two explanations for the "future":

1) A future by subjective/objective time (imagination)

: Picture the future in the brain from memory of past episodes. It is merely an extrapolation from past episodic memory.

2) A future in common time

: Not individuals, but shared images of the "future" and only “predictions”.

These figures of time are consistent with McTaggard's point.

Interpreting Janet’s law

Janet’s law refers to "the length of years that are subjectively remembered," and is "the impression of the length of time we feel when we look back at the past," not "the perceived speed of time that is going on in the present.". For that reason, we think that the Janet’s law comes down to the problem of atomic time. Objective time can be described quantitatively in comparison to a system that operates precisely, such as a clock. In our daily lives, however, it is overwhelming to spend more in primal time or subjective time. There are three main criticisms of Janet’s law:. 1) a depiction of subjective acceleration, not an explanation, 2) the amount of time felt by the same individual varies depending on various factors, and 3) attempts are presently being made to improve the accuracy of predictions about the time felt. This is a very characteristic of primal time. The explanation for Janet’s law is "When humans have new experiences, the memories are strong and haunting and time is long" or, conversely, "When we stop having new experiences, we feel that time is short because there is nothing left in our mind". We discuss this in entropy with respect to the probability density function of the probability space of past episodic memory. When there is less experience, as in childhood, the rate at which past episodic memory increases (the number of new experiences) is relatively higher.

Therefore, when observing changes in entropy, the total number of days at a young age is greater than the number of changes at each moment, resulting in a relatively small change in entropy and a longer primal time. Conversely, as experience increases, the population of episodic memories acquired each day decreases, increasing entropy change. Therefore, it can be interpreted as a short primal time.

Conclusions

To explain subjective psychological time, we applied the HLbC model proposed by the author to how we perceive conscious time. It features the introduction of surreal numbers and the use of past and present information entropy and the second law of thermodynamics in the set to assess differences in psychological time. If we consider psychological time as a numerical value defined by surreal numbers, the difference in information entropy between the past and the present of individual humans can explain the difference in subjective psychological time. It is important to apply consciousness models, including existing models, to many issues of consciousness and to determine their validity and limitations from the perspective of future expansion and modification of models.

References

2. Rovelli C. L’ordine del tempo. United States: Penguin Publishing Group; 2019.

3. Meck WH. Neuropsychology of timing and time perception. Brain and Cognition. 2005 Jun 1;58(1):1-8.

4. Piéron HI Psycho-physiological problems of time perception. The Psychological Year. 1923;24(1):1-25.

5. Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH. Scalar timing in memory. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1984 May 1;423(1):52-77.

6. Zakay D, Block RA. The role of attention in time estimation processes. Advances in Psychology. 1996 Jan 1:143-64.

7. Zakay D, Block RA. Temporal cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 1997 Feb;6(1):12-6.

8. Janet P. L’évolution de la mémoire et de la notion du temps. Paris: A. Chahine; 1928. p. 515.

9. Allen JF. Towards a general model of action and time. Artificial Intelligence. 1984;23(2):123-54.

10. Allen JF, Hayes PJ. A Common-Sense Theory of Time. IJCAI. 1985 Aug 18;1:528-31.

11. Allen JF, Hayes PJ. A Common-Sense Theory of Time: The Longer Paper. TR Computer Science Dept, Univ. of Rochester 1985.

12. Kent L, Wittmann M. Time consciousness: the missing link in theories of consciousness. Neuroscience of Consciousness. 2021 Jan 1;2021(2):niab011.

13. Tononi G. An information integration theory of consciousness. BMC Neurosci. 2004 Nov 2;5:42.

14. Tononi G. Integrated information theory of consciousness: an updated account. Arch Ital Biol. 2012 Dec;150(4):293-329.

15. Tononi G. Consciousness as integrated information: a provisional manifesto. The Biological Bulletin. 2008 Dec;215(3):216-42.

16. Albantakis L, Barbosa L, Findlay G, Grasso M, Haun AM, Marshall W, et al. Integrated information theory (IIT) 4.0: Formulating the properties of phenomenal existence in physical terms. PLoS Comput Biol. 2023 Oct 17;19(10):e1011465.

17. Northoff G, Lamme V. Neural signs and mechanisms of consciousness: is there a potential convergence of theories of consciousness in sight?. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2020 Nov 1;118:568-87.

18. Hebishima H, Arakaki M, Dozono C, Frolova H, Inage S. Mathematical definition of human language, and modeling of will and consciousness based on the human language. Biosystems. 2023 Mar;225:104840.

19. Arakaki M, Dozono C, Frolova H, Hebishima H, Inage S. Modeling of will and consciousness based on the human language: Interpretation of qualia and psychological consciousness. Biosystems. 2023 May;227-228:104890.

20. Kullback S, Leibler RA. On information and sufficiency. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1951 Mar 1;22(1):79-86.

21. Conway JH. On Numbers and Games (2 ed.). United States: CRC Press, 2000.

22. Harry G. An Introduction to the Theory of Surreal Numbers. London Mathematical Society Lecture Note Series. 110. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1986.

23. Ehrlich P. The absolute arithmetic continuum and the unification of all numbers great and small. Bulletin of Symbolic Logic. 2012 Mar;18(1):1-45.

24. Van Den Dries L, Ehrlich P. Erratum to:“Fields of surreal numbers and exponentiation”. Fundamenta Mathematicae. 2001;167(2):173-88.

25. Einstein A. Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper. Annalen der Physik. 1905;322(10):891-921.

26. Iyoda E, Kaneko K, Sagawa T. Fluctuation theorem for many-body pure quantum states. Physical review letters. 2017 Sep 5;119(10):100601.