Commentary

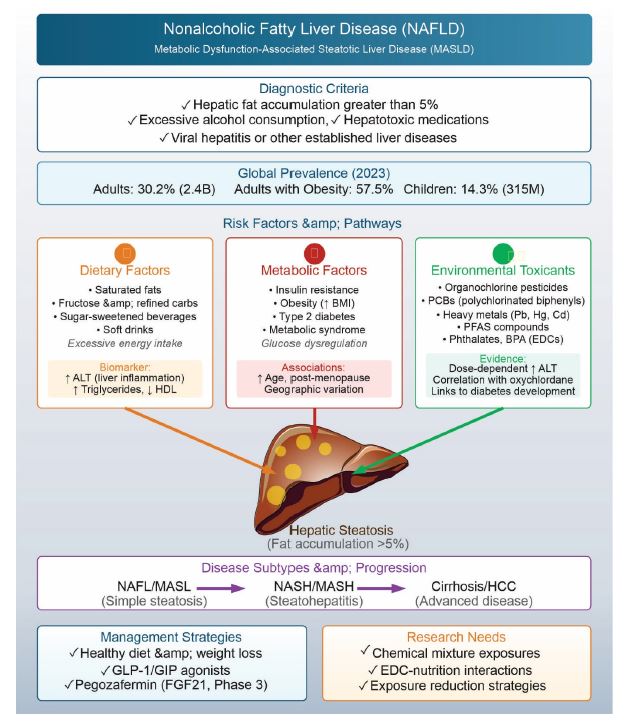

Over the past two decades, global rise in insulin resistance, obesity, and metabolic syndrome has led to a corresponding increase in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [1]. Particularly, NAFLD represents the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is characterized by hepatic fat accumulation exceeding 5% in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption, hepatotoxic medication use, or other established liver diseases such as viral hepatitis [2]. Functionally, NAFLD encompasses two primary subtypes - (i) nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), also known as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver (MASL), and (ii) nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), now known as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) [3]. NASH/MASH is increasingly referred to as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in the current literature. Global prevalence of NAFLD ranges from 20% to 30%, with higher incidence rates documented in the Middle East, South Asia, and Southeast Asia [4–7]. Prevalence of NAFLD increases with age, particularly in post-menopausal women [8]. Current estimates indicate that NAFLD has reached epidemic proportions, affecting approximately 30.2% of all adults, 57.5% of adults with obesity, 14.3% of children, and 38.0% of children with obesity as of 2023 [9]. These figures translate to over 2.4 billion adults and 315 million children worldwide as of 2023, a number that has been steadily increasing and is projected to rise further. (Figure 1) schematically illustrates various aspects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Figure 1. Schematic illustration of various aspects of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Excessive energy intake from saturated fats, fructose, sugar-sweetened beverages, and refined carbohydrates is linked to weight gain and obesity - key contributors to NAFLD development [10]. Nut consumption has been contraindicated in NAFLD management, while prolonged soft drink intake shows prospective association with markers of liver injury, particularly elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels—an indicator of liver inflammation that may develop following NAFLD onset [11,12]. Healthy diet, in comparison to weight reduction, is recommended for the management of NAFLD [13]. Emerging therapeutic approaches include pegozafermin, a PEGylated form of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), currently in Phase 3 clinical trials. As a master metabolic regulator, FGF21 ameliorates hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, obesity, and NAFLD through receptor-mediated mechanisms [14].

Various animal models have been developed to investigate NAFLD pathogenesis and the progression to steatohepatitis (NASH). These models incorporate either genetic modifications or dietary manipulations. Genetic models include sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) transgenic mice, as well as Ob/ob, Db/db, KK-Ay, PTEN-null, PPARα-knockout, AOX-deficient, and MTA1A-deficient mice. Dietary models utilize excessive cholesterol or fructose supplementation, or methionine- and choline-deficient diets [15]. These animal studies underscore nutrition's critical role in NAFLD development, particularly among diabetic and obese older adults. Beyond caloric content, dietary contamination with persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including organochlorine (OC) insecticides, many of which function as endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), has emerged as a significant concern in NAFLD pathogenesis. Animal studies show that exposure to these environmental contaminants may contribute to fat accumulation in liver. Oxychlordane level is correlated with NAFLD in humans while other OC insecticides were not directly associated with NAFLD. However, pesticides, like p, p-DDT, p’p’-DDE are linked to increase in BMI, triglycerides, insulin resistance, and reductions in HDL cholesterol, ailments very common to NAFLD - NAFLD is common to individuals with obesity, metabolic syndrome, and insulin resistance [16]. Serum ALT levels serve as one biomarker for monitoring NAFLD, though with limitations. Population studies reveal that low-level exposures to environmental toxicants demonstrate dose-dependent associations with elevated ALT levels and increased odds ratios for suspected NAFLD in the general U.S. adult population [17]. These environmental toxicants include polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB), phthalates, bisphenol A, mercury, lead, and Cd are known risk factors of NAFLD while limited link between PFAS and NAFLD warrants further research [18,19]. Data from NHANES (2003-2004) indicate significantly elevated liver enzyme levels among individuals with the highest PCB and OC insecticide exposures. Accumulating epidemiological and toxicological evidence supports associations between environmental chemical exposures, particularly PCBs, and NAFLD development [20]. The levels of ALT are not confirmed markers of NALFD; however, its levels are increased during liver injury, alcoholic fatty liver disease and viral liver infection [21,22]. Consequently, using ALT levels to monitor fatty liver disease following industrial chemical exposure has limited reliability [23,24]. The established links between mercury, lead, and liver disease suggest that multiple environmental contaminants may act synergistically, creating conditions that promote hepatic steatosis [25–27].

Exposure to environmental chemicals, such as OC insecticides and other pesticides, are linked to the incidences of diabetes and are components involved in the development of NAFLD. Older women who handled pesticides for agricultural activities in Iowa and North Carolina were found to report higher incidence of diabetes [28]. In addition to OC insecticides, specifically dieldrin, and potentially dioxin-contaminated herbicides, 2,4,5-T and 2,4,5-TP, demonstrated associations with diabetes [29,30]. Besides OC insecticide, exposure to certain organophosphates (OP) also increases the risk of diabetes [28]. Similarly, presence of OC insecticide correlated with the risk of diabetes among North Indian population [31]. Higher levels of β-hexachlorocyclohexane (γ-HCH), dieldrin, and p,p’-DDE, a metabolite of p,p’-DDT, were found in the prediabetes and newly detected diabetic groups as compared to normal glucose tolerance group [31]. The accidental and occupational exposure are reported to modify glucose metabolism, therefore increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance [32,33]. The prevalence of diabetes among people exposed to OP correlated well with the hemoglobin A1c diabetic levels, while chronic treatment of mice with OP for 180 days produced glucose intolerance [34].

Many of the POPs are endocrine disruptors with possible link to development of fatty liver [35]. Animal exposure studies with perfluoralkyl acids (PFAAs), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), and perfluorononanoicacid (PFNA) induce hepatic steatosis [36,37]. Industrial exposure with vinyl chloride increases the sensitivity of hepatosteatosis after high fat diet [18]. Non-POPs, industrial chemicals, such as drugs for chronic usage (e.g., amiodarone, valproic acid, tetracycline, methotrexate, and corticosteroids) are implicated in hepatosteatosis in humans [38–41].

Taken all, current epidemiological surveys inadequately elucidate the complex etiology underlying the burgeoning incidence of diabetes and its relationship to NAFLD. The confluence of POP exposure, industrial chemical contamination, antibiotic usage, and medications for cardiovascular disease appear to increase hepatic lipid accumulation risk, particularly in the context of contemporary overnutrition. Weight loss management through glucagon-like peptide-1 and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide receptor agonist therapy not only improves glycemic control but also reduces hepatic fat content. However, comprehensive animal studies examining defined chemical mixtures are needed to establish definitive links between exposures to environmental chemical mixture and NAFLD development. The worldwide prevalence of NAFLD suggests significant environmental contributions, particularly given the widespread application of OCs, POPs, and OPs. Biological researcher must investigate the combined effects of OC/POP/OP mixture exposure in overnutrition settings to demonstrate whether concurrent nutritional and environmental toxicant/EDC exposures can induce NAFLD. While genetic factors undoubtedly contribute to disease susceptibility, the relatively recent emergence of dietary contaminants that were absent a century ago may represent a critical, modifiable risk factor for NAFLD development. Thorough investigation of these environmental-nutritional interactions could enable risk remediation through exposure reduction strategies and informed development of targeted therapeutic interventions against chemically induced hepatic steatosis.

References

2. Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018 Jul;24(7):908–22.

3. NIDDK. Definition & Facts of NAFLD & NASH. Health Information. United States: NIDDK; 202. Available From:

4. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts.

5. Wong VW, Ekstedt M, Wong GL, Hagström H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023 Sep;79(3):842–52.

6. Athyros VG, Katsiki N, Doumas M. Lipid association of India (LAI) expert consensus statement: part 2, specific patient categories. Clinical Lipidology. 2018 Jan 1;13(1):1–3.

7. Pati GK, Singh SP. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in South Asia. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2016 Jul-Dec;6(2):154–62.

8. Singh S, Kuftinec GN, Sarkar S. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in South Asians: A Review of the Literature. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017 Mar 28;5(1):76–81.

9. Wang J, Wu AH, Stanczyk FZ, Porcel J, Noureddin M, Terrault NA, et al. Associations Between Reproductive and Hormone-Related Factors and Risk of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in a Multiethnic Population. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021 Jun;19(6):1258–66.e1.

10. Amini-Salehi E, Letafatkar N, Norouzi N, Joukar F, Habibi A, Javid M, et al. Global Prevalence of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: An Updated Review Meta-Analysis comprising a Population of 78 million from 38 Countries. Arch Med Res. 2024 Sep;55(6):103043.

11. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016 Jun;64(6):1388–402.

12. Lebda MA, Tohamy HG, El-Sayed YS. Long-term soft drink and aspartame intake induces hepatic damage via dysregulation of adipocytokines and alteration of the lipid profile and antioxidant status. Nutr Res. 2017 May;41:47–55.

13. Witkowska AM, Waśkiewicz A, Zujko ME, Szcześniewska D, Śmigielski W, Stepaniak U, et al. The Consumption of Nuts is Associated with Better Dietary and Lifestyle Patterns in Polish Adults: Results of WOBASZ and WOBASZ II Surveys. Nutrients. 2019 Jun 22;11(6):1410.

14. Carvalhana S, Machado MV, Cortez-Pinto H. Improving dietary patterns in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012 Sep;15(5):468–73.

15. Bailey NN, Peterson SJ, Parikh MA, Jackson KA, Frishman WH. Pegozafermin Is a Potential Master Therapeutic Regulator in Metabolic Disorders: A Review. Cardiol Rev. 2025 Sep-Oct 01;33(5):402–6.

16. Takahashi Y, Soejima Y, Fukusato T. Animal models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 May 21;18(19):2300–8.

17. Sang H, Lee KN, Jung CH, Han K, Koh EH. Association between organochlorine pesticides and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. Sci Rep. 2022 Jul 8;12(1):11590.

18. Cave M, Appana S, Patel M, Falkner KC, McClain CJ, Brock G. Polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, and mercury are associated with liver disease in American adults: NHANES 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2010 Dec;118(12):1735–42.

19. Cave M, Falkner KC, Ray M, Joshi-Barve S, Brock G, Khan R, et al. Toxicant-associated steatohepatitis in vinyl chloride workers. Hepatology. 2010 Feb;51(2):474–81.

20. Pan K, Xu J, Xu Y, Wang C, Yu J. The association between endocrine disrupting chemicals and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2024 Jul;205:107251.

21. Clair HB, Pinkston CM, Rai SN, Pavuk M, Dutton ND, Brock GN, et al. Liver Disease in a Residential Cohort With Elevated Polychlorinated Biphenyl Exposures. Toxicol Sci. 2018 Jul 1;164(1):39–49.

22. Hadizadeh F, Faghihimani E, Adibi P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Diagnostic biomarkers. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2017 May 15;8(2):11–26.

23. Wong VW, Wong GL, Tsang SW, Hui AY, Chan AW, Choi PC, et al. Metabolic and histological features of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with different serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009 Feb 15;29(4):387–96.

24. Brautbar N, Williams J 2nd. Industrial solvents and liver toxicity: risk assessment, risk factors and mechanisms. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2002 Oct;205(6):479–91.

25. Wahlang B, Appana S, Falkner KC, McClain CJ, Brock G, Cave MC. Insecticide and metal exposures are associated with a surrogate biomarker for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003-2004. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2020 Feb;27(6):6476–87.

26. Kang MY, Cho SH, Lim YH, Seo JC, Hong YC. Effects of environmental cadmium exposure on liver function in adults. Occup Environ Med. 2013 Apr;70(4):268–73.

27. Lin YS, Ginsberg G, Caffrey JL, Xue J, Vulimiri SV, Nath RG, et al. Association of body burden of mercury with liver function test status in the U.S. population. Environ Int. 2014 Sep;70:88–94.

28. Yorita Christensen KL, Carrico CK, Sanyal AJ, Gennings C. Multiple classes of environmental chemicals are associated with liver disease: NHANES 2003-2004. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2013 Nov;216(6):703–9.

29. Starling AP, Umbach DM, Kamel F, Long S, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Pesticide use and incident diabetes among wives of farmers in the Agricultural Health Study. Occup Environ Med. 2014 Sep;71(9):629–35.

30. Remillard RB, Bunce NJ. Linking dioxins to diabetes: epidemiology and biologic plausibility. Environ Health Perspect. 2002 Sep;110(9):853–8.

31. Rylander L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Hagmar L. A cross-sectional study of the association between persistent organochlorine pollutants and diabetes. Environ Health. 2005 Nov 29;4:28.

32. Tyagi S, Mishra BK, Sharma T, Tawar N, Urfi AJ, Banerjee BD, et al. Level of Organochlorine Pesticide in Prediabetic and Newly Diagnosed Diabetes Mellitus Patients with Varying Degree of Glucose Intolerance and Insulin Resistance among North Indian Population. Diabetes Metab J. 2021 Jul;45(4):558–68.

33. Bertazzi PA, Bernucci I, Brambilla G, Consonni D, Pesatori AC. The Seveso studies on early and long-term effects of dioxin exposure: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 1998 Apr;106 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):625–33.

34. Longnecker MP, Michalek JE. Serum dioxin level in relation to diabetes mellitus among Air Force veterans with background levels of exposure. Epidemiology. 2000 Jan;11(1):44–8.

35. Velmurugan G, Ramprasath T, Swaminathan K, Mithieux G, Rajendhran J, Dhivakar M, et al. Gut microbial degradation of organophosphate insecticides-induces glucose intolerance via gluconeogenesis. Genome Biol. 2017 Jan 24;18(1):8.

36. Foulds CE, Treviño LS, York B, Walker CL. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017 Aug;13(8):445–57.

37. Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, Lai D, Pfahles-Hutchens A, Seed J. Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings. Toxicol Sci. 2007 Oct;99(2):366–94.

38. Chang ET, Adami HO, Boffetta P, Cole P, Starr TB, Mandel JS. A critical review of perfluorooctanoate and perfluorooctanesulfonate exposure and cancer risk in humans. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2014 May;44 Suppl 1:1–81.

39. Rabinowich L, Shibolet O. Drug Induced Steatohepatitis: An Uncommon Culprit of a Common Disease. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:168905.

40. Anthérieu S, Rogue A, Fromenty B, Guillouzo A, Robin MA. Induction of vesicular steatosis by amiodarone and tetracycline is associated with up-regulation of lipogenic genes in HepaRG cells. Hepatology. 2011 Jun;53(6):1895–905.

41. López-Riera M, Conde I, Tolosa L, Zaragoza Á, Castell JV, Gómez-Lechón MJ, et al. New microRNA Biomarkers for Drug-Induced Steatosis and Their Potential to Predict the Contribution of Drugs to Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front Pharmacol. 2017 Jan 25;8:3.

42. Sakthiswary R, Chan GY, Koh ET, Leong KP, Thong BY. Methotrexate-associated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with transaminitis in rheumatoid arthritis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:823763.